DPR Construction has been saved

DPR Construction A case study in work environment redesign

20 June 2013

- Karin Chen

Innovative uses of technology and adaptive physical workspaces contribute to DPR Construction’s ability to rapidly test and scale new ideas.

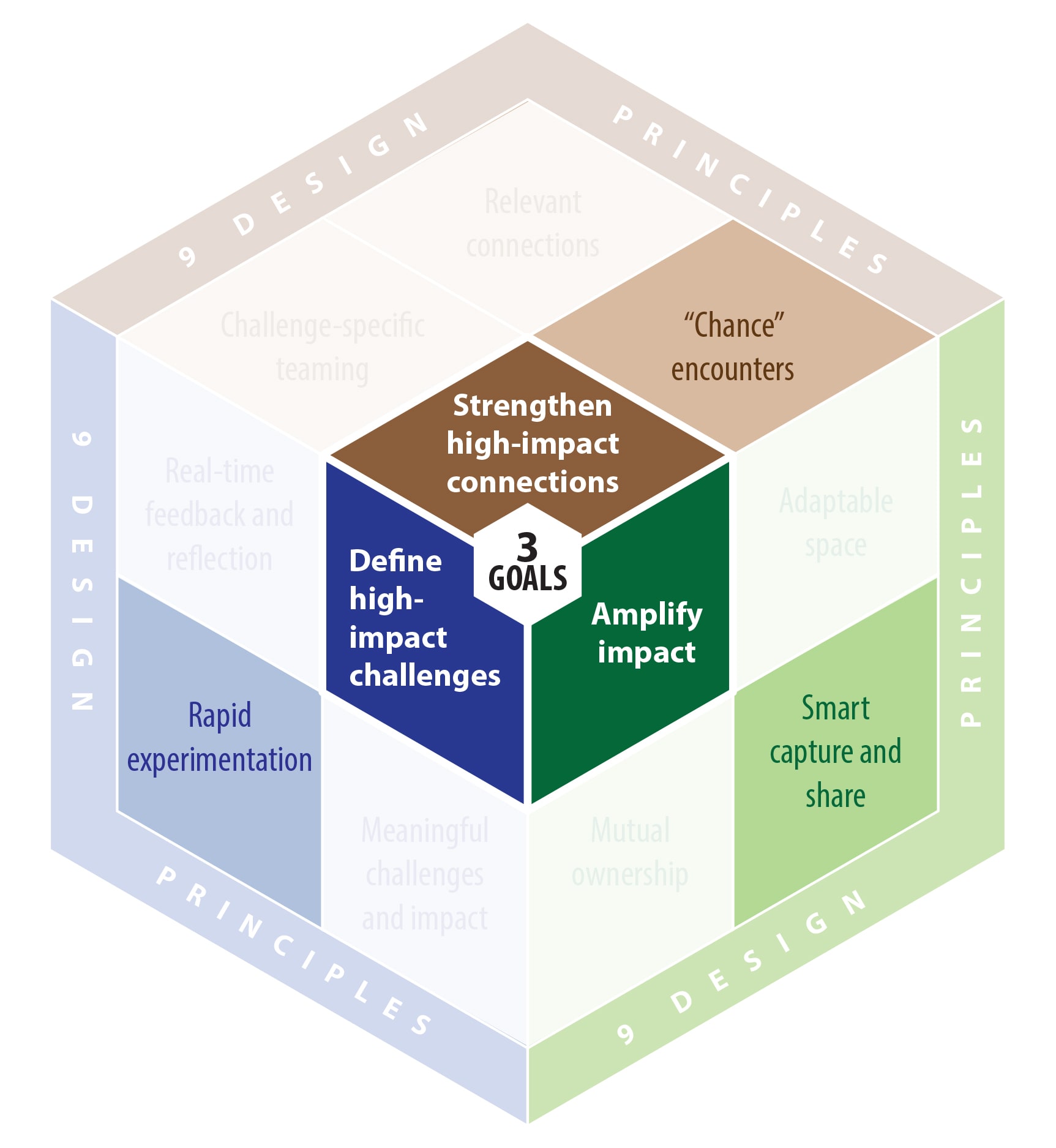

Can the way the workplace is constructed—physically, virtually, and managerially—affect employee performance? The Deloitte LLP Center for the Edge report Work environment redesign, based on a study of more than 75 organizations, argues that the work environment can have a critical impact on employee productivity, passion, and innovation. The study outlines nine design principles that can help employers gain more value from their people.

This case study explores ways that DPR Construction, a contracting and construction managing company, is applying these design principles to enhance its own corporate environment.

Figure 1. Work environment design principles used at DPR Construction

Company background and results

DPR Construction is a privately held, employee-owned building contractor and construction managing company. DPR’s “ever forward”1 mentality of self-improvement drives innovation in the construction industry, which has remained largely stagnant for the last century. Completing over 7,600 projects since it was founded in 1990, DPR now boasts $2.4 billion in revenue and employs 2,600 full-time staff members, over half of whom are front-line craft workers.2 DPR earned 15th place on Fortune’s “100 best companies to work for” in America in 2013,3 its fourth consecutive year on the list.4 DPR attributes much of its success to a tight focus on fast innovation, quantifiable impact, and employee ownership of results.

Forming the innovation team

In 2008, DPR’s management team noticed that the company’s astronomical growth and success were starting to create a culture of complacency. To encourage rapid innovation and applied learning, management asked a set of 30 young employees to research the most innovative practices across all industries globally and apply them to DPR. This innovation team’s charter was to:5

- Develop an idea-promoting infrastructure

- Develop criteria and a process for choosing ideas

- Develop an idea rollout process

- Generate organizational enthusiasm for innovation

- Engage all levels of the organization without over-shaping

By 2010, four members of the operations group had been chosen to become part of a full-time innovation team. First, they held innovation workshops in every region to align the organization around DPR’s vision of innovation and related support systems. Next, DPR rolled out a customized online meeting space, or “idea marketplace,” that enabled employees to share, debate, and develop ideas across global geographic and functional siloes. This platform promoted and encouraged learning at the individual, team, and, eventually, organizational level. As DPR project engineer Daniel Tran states, “Elevating our corporate IQ was the real end goal, not just increasing overall awareness of ideas.”6 The innovation team was allocated a $1.2 million budget to invest in and manage the implementation of fast-tracked ideas. To drive action, employees also voted on ideas to quickly improve company performance.7

Smart capture and share

The innovation team helps to uncover, invest in, and scale leading ideas from employees across the company. In one instance, several engineers had an idea about how to improve the process of updating construction drawings, or blueprints. Traditional paper rolls of blueprints cost approximately $2,000, are cumbersome to update, and are slow to print and deliver. On many DPR construction projects, plans are adjusted constantly; mistakes can easily occur when everyone is working off a slightly different version. With the help of the innovation team, DPR decided to implement a new cloud storage technology to access drawings from tablets instead of paper rolls so that plans could be updated in real time and shared with all locations immediately. Tablets also gave workers the benefit of being able to zoom in on details. The company immediately saved money, and fewer mistakes were made.8

In addition to the tablets, the innovation team also invested in test field kiosks at job sites—sophisticated computers with large screens for complex 3D modeling and for viewing and reworking full drawings. This solution, together with the tablets, solved a long-standing construction problem of obtaining up-to-date information in the field while reducing the volume of paper drawings employees needed to carry around. Real-time drawings that live dynamically “in the cloud” allow workers onsite and in the office to smart capture and share accurate, up-to-date data, allowing them to stay in sync: All changes are automatically pushed to colleagues so everyone has the correct version. Beyond enabling savings of tens of thousands of printing dollars per project, the technology also saved workers time: In a pilot study, project engineers saved 5.8 hours per week, and superintendents saved 7.5 hours per week, because of the drastic reduction in the need to run back and forth between sites to gather information and paper.9

Rapid experimentation

In another example of scaling an innovative experiment, one graduate engineer who joined DPR in 2011 helped to develop a company-wide SketchUp component library of 3D virtual mockups. While working on a hospital project, the engineer created component mockups from scratch for over 30 different hospital rooms. Each room contained many components, such as architectural features, data and power outlets, furniture and cabinets, medical equipment, and so on. The first few rooms took two days per room to accurately model all of the required components and then arrange them appropriately. During this process, the engineer built his own component library and starting reusing components whenever possible, significantly reducing the time and effort required to create the room mockups. The last few rooms for the hospital took less than two hours each to complete.10

After seeing how effective this process was, the engineer began to collect ready-to-use components created by his colleagues to add to his library and to share with his team. At first, the teams used a shared drive to access the shared content. But after receiving positive feedback from employees through Spigit, the innovation team chose to fast-track the development of a more robust content library. They expanded the library and housed it in a simple executable file that contained all of the content, so that all workers could immediately access the collection. This instance of rapid experimentation, in which one engineer’s isolated experiment led to company-wide implementation, helps DPR’s engineers create virtual mockups and site logistics plans in a fraction of the time it took before—and with higher quality.11

Outside of institutionalized programs, DPR tries to infuse innovation into all areas of the organization’s day-to-day operations. On the job site, teams constantly strive for more efficient ways to construct buildings. One strategy, for instance, is to build as much as possible in the shop beforehand, as opposed to on the actual job site. This procedure helps save on labor costs, as labor in the shop is less expensive than field labor. It also reduces congestion onsite, which can significantly delay operations.12

When building a hospital, one project engineer noticed that the bathrooms in hospital patient rooms were arranged back to back. He postulated that dozens of these “double bathrooms” could be pre-fabricated almost entirely offsite and then slotted into the building like a puzzle piece. The innovation team agreed to invest $30,000 for a prototype to be built in Arizona (where labor was cheaper) and transported back to the construction site in California. After a few tweaks to the prototype, this new building technique became functional. This relatively small investment in rapid experimentation has the potential to save six to eight weeks in build time and labor costs,13 a significant amount for a multi-million dollar construction project.

“Chance” encounters

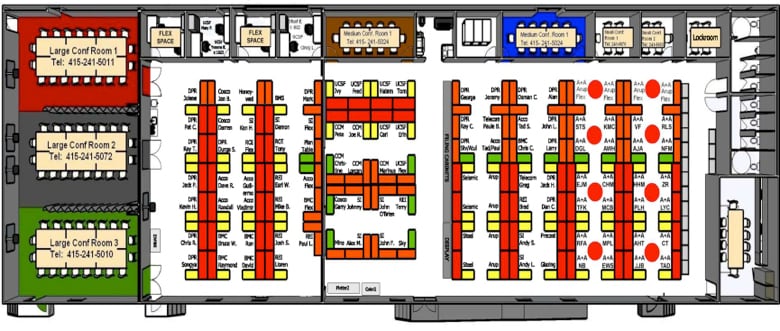

DPR encourages collaboration to help teams innovate. On job sites, workers often connect 10–40 mobile trailers together to form a single “Bigroom” to congregate in (see figure 2). The Bigroom is used for weekly all-hands meetings and also includes many conference rooms for smaller meetings, increasing communication and the likelihood of “chance” encounters among many onsite groups.14

Figure 2. Typical Bigroom layout

On one project, DPR became familiar with a 3D modeling software package called Tekla, traditionally used for detailing structural steel. When a few DPR engineers noticed in the Bigroom how effectively a team of subcontractors used this software to model concrete and reinforcing bar, ideas began to circulate about what other nontraditional construction scopes this software could model. There were concerns about accuracy and coordination in the construction of the the exterior façade using current methods, so one team member suggested the idea of modeling the entire façade in Tekla—a process that had not been done before. When the team executed the proposed model in Tekla, they identified several design and coordination issues before fabrication of the façade began, saving the project from potential schedule delays and budget overruns.15 This “chance” encounter with subcontractors in the Bigroom, coupled with a willingness to innovate, resulted in a higher-quality façade design and a better-coordinated construction process.

It turned out that not even Tekla had thought of applying its tool to exterior façades. The above project received Tekla’s 2010 North American BIM Award, and then the Global BIM Award, bestowed by industry specialists for projects showcasing the versatility of the product on a successful construction project.16

Lessons learned

- Don’t just source innovative ideas—make calculated bets and dedicate resources to implementing the leading ideas. This benefits the company and helps employees feel ownership over performance improvement.

- Develop forums, tools, and encouragement to allow geographically dispersed employees to collaborate and engage in idea sharing and dialogue.

- Create opportunities for groups that wouldn’t normally interact to collaborate, physically or virtually, to elevate performance.