Unlocking the passion of the Explorer has been saved

Unlocking the passion of the Explorer A report in the 2013 Shift Index series

17 September 2013

By adopting new ways of working focused on eliciting and amplifying the passion of certain workers, organizations will benefit from the sustained performance improvement that these individuals create.

About the Shift Index

We developed the Shift Index to help executives understand and take advantage of the long-term forces of change shaping the US economy. The Shift Index tracks 25 metrics across more than 40 years. These metrics fall into three areas: 1) the developments in the technological and political foundations underlying market changes, 2) the flows of capital, information, and talent changing the business landscape, and 3) the impacts of these changes on competition, volatility, and performance across industries. Combined, these factors reflect what we call the Big Shift in the global business environment.

For more information, please go to www.deloitte.com/us/shiftindex

Executive Summary

In a world of uncertainty and mounting performance pressure, organizations face a significant challenge. On the one hand, more powerful and less loyal consumers demand more value; on the other, more powerful and less loyal workers demand higher compensation and a work environment that supports their development. In this environment, organizations need workers with passion to realize extreme sustained performance improvement.

While much work has been done to understand and improve employee engagement, employee engagement is no longer enough. Times have changed. Worker passion—defined by three attributes rather than static skills that rapidly diminish over time—will be critical as we shift from a twentieth-century world characterized by scalable efficiency to a twenty-first-century world amplified by scalable learning.

We must figure out how to thrive—and not simply survive—in this new uncertainty, and we believe that individuals with worker passion will be the key. Three attributes characterize worker passion: Commitment to Domain and Questing and Connecting dispositions. Commitment to Domain can be understood as a desire to have a lasting and increasing impact on a particular industry or function. Workers with the Questing disposition actively seek out challenges to rapidly improve their performance. Workers with the Connecting disposition seek deep interactions with others and build strong, trust-based relationships to gain new insight. Together these attributes define the “passion of the Explorer”—the worker passion that leads to extreme sustained performance improvement.

While passion of the Explorer is easy to find in the worlds of online gaming and extreme sports, it is largely absent in the corporate environment. Results from a recent Deloitte survey of the US workforce reveal that only 11 percent have all three attributes that make up worker passion. The results are not surprising, considering many of our organizations are still structured to maximize efficiency by way of clearly defined roles and tightly integrated to eliminate variance against forecasts. The individuals exhibiting the three attributes—Commitment to Domain and Questing and Connecting dispositions—may struggle with clearly defined roles, organizational silos, and predictability.

To cultivate and nurture worker passion, organizations can redesign their work environments—the integration of the physical environment, virtual environment, and management systems. By adopting new ways of working focused on eliciting and amplifying worker passion, organizations will benefit from the sustained performance improvement that these individuals create. As individuals and leaders, we all have a role to play as we look to improve our performance and reach our full potential in an unpredictable world.

This report is meant to start the discussion around worker passion—and we welcome your thoughts, questions, and partnership as we continue to study this important topic.

To better understand this year’s Shift Index, as well as to learn about ways to begin to create and capture value in this environment, we invite you to take a deeper look at our 2013 Shift Index research reports:

From exponential technologies to exponential innovation

Success or struggle: ROA as a true measure of business performance

2013 Shift Index metrics: The burdens of the past

Lessons from the edge: What companies can learn from a tribe in the Amazon

Dave Hoover believes in hiring for dispositions over skills. Trained as a child- and family-therapist, he started teaching himself HTML code in 1999 and became a software developer in 2000.2 When he was hiring, Dave looked for individuals who “were relentlessly resourceful. The kind of person where if they tell you they’re going to do something, they just get it done. [You] would never have to worry about this person’s long-term success.”3 Although he didn’t know it at the time, Dave had identified what we call the “passion of the Explorer” and was hiring those individuals who seemed to possess this type of passion for work. And these individuals did succeed. Of the 58 workers who completed some form of the apprenticeship program since 2007, 80 percent are still with the company.4Dave Hoover knew that luring engineering talent with higher compensation was increasingly a losing proposition. It was 2007, and the “chief craftsman” of Obtiva, a software development consultancy in Chicago, needed to grow his company, but he found out that web and mobile designers and developers were in short supply and high demand. Obtiva, then a five-person team, was competing for talent with established companies able to offer higher compensation and more prestige. Dave had little choice but to look for “diamonds in the rough”—aspiring software engineers with the right dispositions who lacked specific skills and experience—and put them in an environment where they could learn and improve quickly. Obtiva’s apprenticeship program was born. By supplementing traditional hiring with the apprenticeship program, Dave was able to grow his team of 5 into a consultancy of 50 and then into an engineering department of 500 after Obtiva was acquired by Groupon in 2011.1

Explorers are able to realize their full potential in their chosen domain and contribute more value to the enterprise.

The Explorer represents only one segment that we identified in the workforce—but it is one well-suited for helping an enterprise succeed in today’s fluid, competitive environment. This is what we mean when we talk about worker passion. These individuals are passionate about their work, and their passion could be a key to unlocking sustained extreme performance improvement, both at a personal and institutional level. Through their passion, Explorers are able to realize their full potential in their chosen domain and contribute more value to the enterprise.

In this report, we will examine how workers with the passion of the Explorer can help companies navigate today’s rapidly changing world and how leaders can foster the dispositions of the Explorer by redesigning the work environment. Our report is an initial step in understanding worker passion and connecting this passion to performance—more work needs to be done in this area. We welcome others to join in the conversation.

What do we mean by “disposition”? A disposition is an individual’s orientation toward specific actions. As defined by Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown, “Dispositions are not mental functions (like learning), they are statements of propensity, what people are likely to do in particular situations.”5 Dispositions cannot be taught but may be cultivated and can be activated through appropriate triggers in the environment. For the purpose of this paper, dispositions are a set of tendencies or inclinations that serve as platforms for skills development.

By identifying and cultivating the passion of the Explorer within their workforces and creating teams of passionate individuals engaged in learning new skills, organizations will be more able to address challenges and realize opportunities in today’s turbulent world. While the rapidly changing business environment causes skills to become obsolete more quickly, dispositions endure; workers exhibiting the passion of the Explorer continuously renew and refresh their skills and in turn, provide additional value to their teams, organizations, and ecosystems.

The challenge

Obtiva is not the only company to face talent and performance pressures, and these challenges are not limited to the software engineering field. Today, many companies find themselves squeezed from both sides: more powerful and less loyal consumers demand more value, and more powerful and less loyal workers demand increased compensation and other concessions.6 Consumer power is driven by increased availability of information, increased offering variety, and low switching costs, all of which allow consumers to get more for less. The power of talent is reflected in the continuing rise of both the compensation and relative value of creative workers7 as companies’ increasing dependence on creative talent leads to talent shortages and turnover. Through platforms like LinkedIn and Glassdoor, workers have more visibility into their career options and have more bargaining power and ability to negotiate as a result. While companies struggle to acquire and retain top talent, the useful life of many skills is declining—now averaging about five years—creating a constant need for new talent to address skill gaps.8

As a result of these pressures, US firm performance has steadily declined over the past 47 years and shows no sign of stabilizing. The 75 percent decline in return on assets (ROA) since 19659 means that companies need more and more resources to create value.10 To combat the negative ROA trend in the short-term, many companies resort to measures such as cost cutting, layoffs, or outsourcing. These measures, however, have failed to reverse the long-term trend for the US economy. Clearly, doing the same thing faster and with more and more resources is not the answer.

In the world of rapid change and mounting pressures, individuals and companies need to develop capabilities that enable them to constantly learn and improve performance. Yet the mounting pressure can be stressful, especially when individuals are locked into institutions and practices that are constraining. “A significant portion of the American workforce is burned out, and … that’s rising,” says Richard Chaifetz, CEO of ComPsych Corp., a Chicago-based provider of employee assistance programs. In a 2012 survey of 1,880 US workers administered by ComPsych, 63 percent reported having high levels of stress at work, including extreme fatigue and feeling out of control, and 39 percent cited workload as the top cause of stress.11 Such workers become less engaged and less productive. A certain type of worker, however—those with the passion of the Explorer—thrives in the rapidly changing environment. Instead of getting discouraged by challenges, Explorers get excited. They embrace challenges as opportunities to learn new skills and rapidly improve performance.

The apprentices hired by Dave Hoover exemplify this type of individual. They welcomed challenges to learn new, and sometimes daunting, software skills. They connected with others in the broader ecosystem of software engineers by participating in open source communities such as GitHub. They aspired to build impactful careers as software engineers. The apprentices demonstrated the passion of the Explorer, which can lead to superior performance improvement in the world of constant change.

In search of the right dispositions

In today’s dynamic and rapidly changing world, the concept of resilience becomes increasingly important. In his book The Age of the Unthinkable, Joshua Cooper Ramo described the relationship between the pace of change and the need for resilience:

“Learning to think in deep-security terms means largely abandoning our idea that we can deter the threats we face and, instead, pressing to make our societies more resilient so we can absorb whatever strikes us. Resilience will be the defining concept of [the] twenty-first century…, as crucial for your fast-changing job as it is for the nation.”12

Many business executives today view resilience as an ability to withstand pressure—a fortress comes to mind. Ramo’s definition is slightly different: Resilience is “a measure of how much disturbance a system can absorb before it breaks down so fundamentally that it cannot easily return to the way it once was….” He describes the effective resilience systems as those that evolve. “They don’t just bend and snap back. They manage to get stronger because of the stress. They capture the good from avalanches of change without letting the bad wipe them out.”13 In this way, resilience is more like an immune system than a mechanical system.

With mounting pressures and uncertainty in the business environment unlikely to decrease, organizations that learn from unexpected challenges and do not crumble under pressure will be better positioned for long-term success. Such resilience stems from having a workforce with a preponderance of individuals who make a long-term commitment to a domain and possess two specific dispositions or orientations toward actions. Combined, these three attributes define the passion of the Explorer:

Commitment to Domain—Long-term commitment can be understood as a desire to have a lasting and increasing impact on a particular domain (industry sector or function) and a desire to participate in the domain for the foreseeable future. Commitment to Domain helps individuals focus on where they can make the most impact. Having domain context enables an individual to learn much faster, allowing for cumulative learning. This commitment, however, does not imply isolation or tunnel vision. Quite the opposite: these individuals are constantly seeking lessons and innovative practices from adjacent and new domains that have the potential for impact within their chosen domain.

. . . organizations that learn from unexpected challenges and do not crumble under pressure will be better positioned for long-term success.

Questing—The Questing disposition drives workers to go above and beyond their core responsibilities. Workers with the Questing disposition constantly probe, test, and push boundaries to identify new opportunities and learn new skills. Resourceful and imaginative, they try to identify novel ways of using the tools and resources available to them to improve their performance. These workers actively seek challenges that might help them achieve the next level of performance and explore the undiscovered. If they cannot find these challenges, individuals with a Questing disposition get frustrated by the pace of learning and move to another environment (team or organization) that does offer these opportunities.

Connecting—The Connecting disposition leads individuals to seek out and interact with others to share interests. Although workers may intuitively understand that an effective way to advance is to connect with and learn from others, workers with a Connecting disposition often seek deep interactions with others in related domains to attain insight that they can bring back into their own domain. Workers driven by the Connecting disposition build connections, not to grow their own professional networks, but to seek out experts and continue to learn and develop no matter how knowledgeable they already are.

Passion of the Explorer in extreme sports

A passionate surfer for the last 19 years, Matt Schutte is no stranger to challenging big wave locations like Mavericks near Half Moon Bay, California. Unfortunately, during the spring and summer months, the San Francisco climate where he lives is known more for wind than big waves. “If the waves aren’t great, surfing is not fun for me anymore. When there are specific conditions and the waves are good, there’s a playground. But here, that’s only 6 months out of the year.”

Looking for a new challenge, Matt turned to kite-surfing. Although the ocean was familiar, kite-surfing required a new skillset. To acquire that skillset, Matt needed a new ecosystem. When he attempted to configure his equipment on the beach on day one, he was out of luck—nobody knew how to set up the bar correctly. Unable to get off the sand, he spent the rest of the afternoon at his laptop, downloading manuals and learning how to configure his equipment by watching videos on YouTube.

Matt continues to attract and access a variety of resources to learn rapidly and constantly improve. Matt is constantly learning new tricks and achieving new levels of performance. “I pick people’s brains while at the beach, observe others, and watch tutorials on YouTube. I’m constantly learning about a variety of things.”

Currently, Matt has a few challenges in mind: most notably, a backflip/grab combination known as a strapless back roll. Some of the resources Matt found online described how body weight corresponds to the type of kite. An Internet search resulted in a spreadsheet already developed by a member of the kite-surfing ecosystem. The spreadsheet suggested kites for certain ranges of body weight. That helped him build up a knowledge base that now enables Matt to take a quick look at the water and instantly know which kite will suit him based on the weather conditions that day.

Matt is an Explorer, exhibiting the three attributes in his newest extreme sport. Matt is committed—finding it hard to stay inside when the wind is howling. Matt is on a quest—always improving, accomplishing new challenges, and pushing himself to new levels of performance. And Matt is connecting—with friends, communities, and the broader virtual ecosystem.

Collectively, these attributes characterize what we call “the passion of the Explorer.” It is this passion of the Explorer that leads workers to accelerated learning and performance improvement to the benefit of both the individual and the organization. Commitment to Domain helps Explorers maintain long-range goals and perspective despite short-term disruptions. The Questing disposition builds knowledge and skills as Explorers embrace challenges as opportunities to learn and get stronger. The Connecting disposition leads the Explorers to build the strong, trust-based relationships essential for collaboration, rapid feedback, and reflection. Together, the Commitment to Domain and Questing and Connecting dispositions create the type of resilience that is critical for increasing performance in today’s rapidly changing world.

The passion of the Explorer is easy to spot in two worlds we have followed for years—online gaming and extreme sports. Both are environments characterized by extreme performance improvement. In such environments, groundbreaking leaps in performance occur frequently, for the individual as well as for the entire community. For example, each year at the X Games—a sporting event focused on extreme sports such as skateboarding, BMX biking, and snowboarding—new tricks are introduced and entirely new events revealed. There is no question that these athletes are good; what is interesting is that they are getting better and better. The individuals that strive in these types of environments demonstrate the commitment and dispositions of the Explorer.14 They are committed to their sport, they are constantly attempting new challenges to learn and improve their skill levels, and they participate in robust communities of like-minded individuals where tips, tricks, and advice are shared. “Taking on new challenges is fun! I love the adrenaline rush and the sense of accomplishment associated with mastering a trick or riding a wave for the first time,” says Matt Schutte, a passionate big wave surfer who is now learning kite-surfing (see sidebar 1 for more about Matt’s experience). He relies on the kite-surfing community and online resources (such as discussion boards and YouTube videos) to advance his skills.15

It is not surprising to find passion in extreme sports. In these environments, athletes get to select their own challenges, failures are embraced as learning opportunities rather than punished, and successes are celebrated. In contrast, the passion of the Explorer is much harder to find in the workplace.

Passion versus engagement

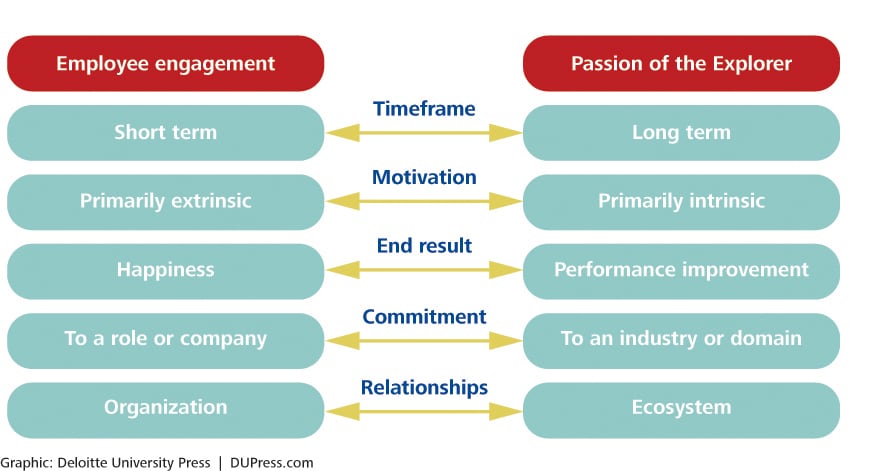

Worker passion is not employee engagement. Employee engagement is a snapshot used by management to assess emotional commitment to organizational goals, rewards systems, work-life fit, and other initiatives. Engaged employees look forward to showing up, building friendships, and feeling connected to the company’s mission.

Companies such as Gallup often run nationwide surveys to gather feedback around the following areas related to employee engagement:

- I know what is expected of me at work.

- In the last seven days, I have received recognition or praise for doing good work.

- There is someone at work who encourages my development.

- My associates or fellow employees are committed to doing quality work.

- I have a best friend at work.16

Gallup found that employee engagement leads to improved performance at the workplace. Organizations at the top quartile of engagement have significantly higher profitability and customer ratings, less turnover and absenteeism, and fewer safety incidents than those in the bottom quartile. They also seem to have higher earnings per share.17

While employee engagement was sufficient in a world of predictability that was designed to optimize scalable efficiency, engagement will be insufficient in a world of unpredictability, constant change, and disruption.

What’s missing from the typical discussion of employee engagement is a commitment to achieving full potential and a relentless focus on performance improvement. Engaged employees are often content with their work but don’t have the desire to reach the next level of performance. Engaged employees often enjoy stability, predictability, and the environment they are in and may lack the urge to challenge established processes as a result.

In 2012, approximately 30 percent of the US workforce was engaged18 versus the 11 percent who have the passion of the Explorer. Both low levels will have significant implications for the US economy and individual performance today and in the future.

The following graphic summarizes the differences between employee engagement and the passion of the Explorer.

The Explorer in the work environment

The Explorer, as defined above, is hard to control or manage in the context of a traditional corporation organized around detailed plans and forecasts. Indeed, many companies today are structured such that they actively discourage passion. In twentieth-century corporations built for scalable efficiency, jobs were well defined and organized to support processes designed to meet plans and forecasts. Workers were trained to protect company information, and any collaboration with those outside of the organization was highly monitored or even discouraged. Most innovation was driven from within the company’s four walls, often without feedback or customer interaction.

In these environments, the Explorer’s attributes are threatening. An Explorer’s Commitment to Domain could overshadow loyalty to the firm, if the right challenges and opportunities are not present within that environment. Questing behaviors often expand beyond the defined job description and are likely to introduce unexpected variance to the plan. Connecting with others outside the organization could be deemed risky.

The persistence of this traditional approach in the twenty-first century may, in part, explain why there are so few Explorers in today’s workforce. In the fall of 2012, Deloitte Center for the Edge surveyed19 approximately 3,000 US workers (>30 hours per week) from 15 industries and across various job levels (senior management, middle management, and front line) to assess workers’ dispositions.20 Only 11 percent of the US workforce possessed all three attributes—Commitment to Domain and Questing and Connecting dispositions —that characterize Explorers with the type of passion that leads to accelerated learning and performance improvement.

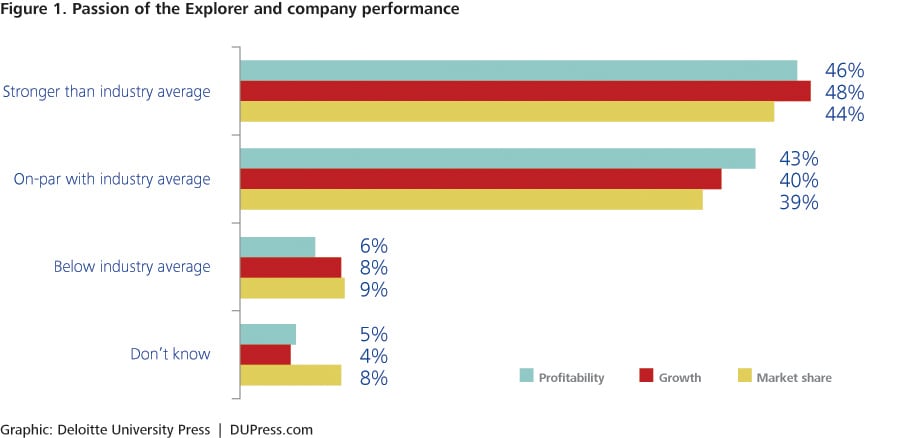

Overall, Explorers reported that the companies they work for perform better in the marketplace (see figure 1). Approximately 46 percent, 48 percent, and 44 percent of the Explorers report that their companies perform stronger than the industry in terms of profitability, growth, and market share respectively, and less than 10 percent believe their companies perform below the industry average.

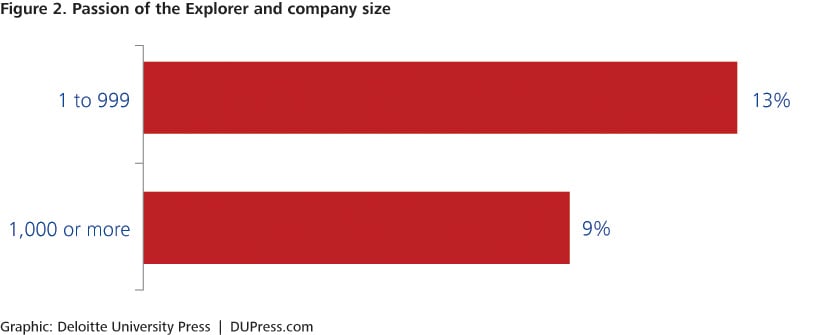

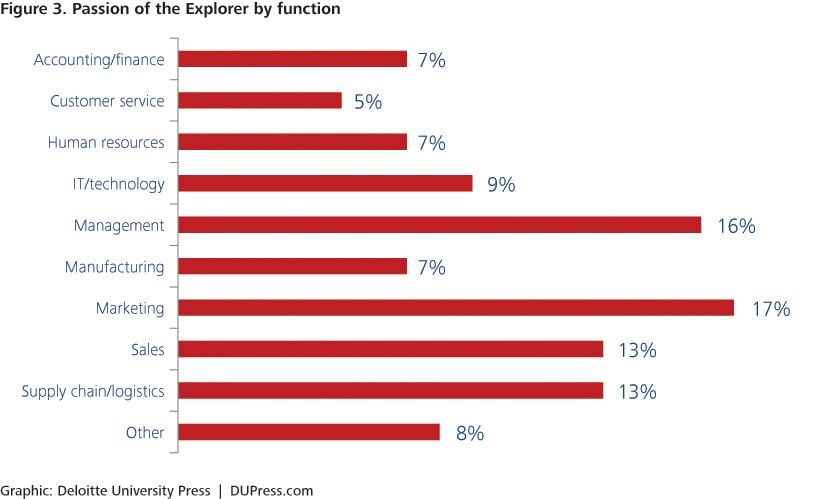

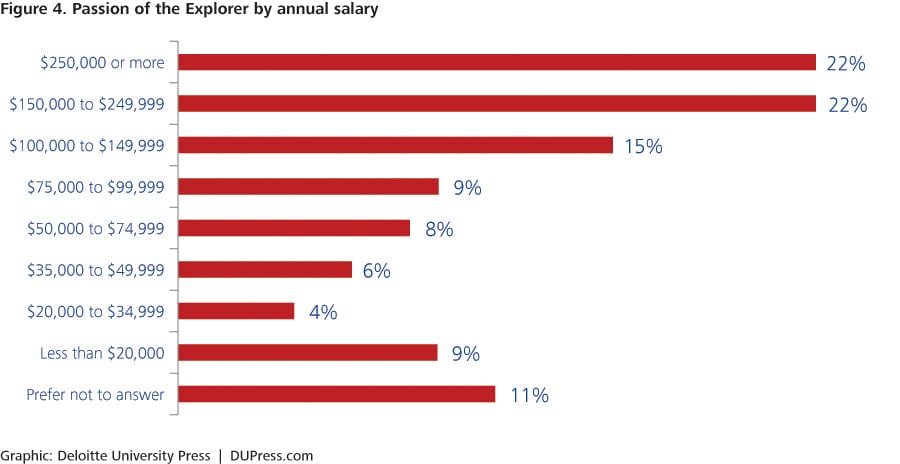

Interestingly, the passion of the Explorer was not equally distributed across the workforce. Explorers tend to work for smaller companies. They also command higher compensation and are more prevalent in the management and marketing functions. At the same time, worker passion does not appear to concentrate in any particular industry. (See figures 2–4 for highlights from the survey.)

Explorers are more heavily represented in companies with less than 1,000 people. The prevalence of workers with the passion of the Explorer drops from 13 percent to 9 percent in companies with more than 1,000 employees (see figure 2).

Explorers are more likely to be in management (17 percent) or marketing (16 percent) functions and are less likely to reside within customer service (5 percent), accounting/finance (7 percent), human resources (7 percent), or manufacturing (7 percent) functions (see figure 3).

Passion of the Explorer correlates with compensation. Among those making more than $150,000, 44 percent are Explorers versus just 15 percent or fewer in lower income brackets (see figure 4).

Most of these findings are not surprising, given the aspects of the work environment that fuel the passion of the Explorer. In smaller companies, individuals tend to have more control of their jobs and also more clarity around how their actions impact the overall objectives of the company. In smaller companies, this sense of impact and autonomy may also extend outside the organization, such that they are more attuned and motivated to make a difference in the broader industry or domain.

In terms of function, more freedom, autonomy, and room for creativity are characteristics of the marketing and management functions. These functions allow and often require individuals to connect with others within and outside of the company in order to learn new practices and cutting-edge techniques. Similarly, individuals in marketing and management roles often have a better sense of how their work impacts specific aspects of the company as well as its overall performance.

Finally, it is not surprising that Explorers are more prevalent in the higher income brackets. Highly-compensated individuals tend to have more freedom to make important business decisions and occupy roles that yield a greater sense of autonomy and impact. The corollary is also likely; individuals who possess the attributes that comprise the passion of the Explorer tend to be more successful and able to command higher compensation.

Individuals who possess the passion of the Explorer also tend to report working in environments that differ from those of traditional twentieth-century corporations. When asked about the degree to which their organizations had characteristics associated with collaboration, learning, and improvement—for example, encouraging workers to take initiative or voice their opinions—the Explorers rated their organizations consistently better than the rest of survey respondents (see figure 5), generally regardless of company size.

For example, when asked if their companies embrace a culture of learning and development, the Explorer responses averaged 5.5 (on a 7-point scale where 7 is “completely agree”) while the rest of the workforce averaged 4.4. Explorers were more likely to report being encouraged to work cross-functionally (average response of 6.1 versus 4.9 for the rest of the workforce) and to being encouraged to work on projects of interest outside their direct responsibilities (5.4 versus 4.0). Also, Explorers reported more engagement with customers to innovate on new product and service ideas (5.6 versus 4.4) and more collaboration with outside experts (5.3 versus 4.4). Finally, Explorers were more likely than the rest of the workforce to report having sufficient autonomy to achieve their goals at work (5.9 versus 5.0).

In terms of organizational structures, the results suggested that many organizations are not perceived to be flat. For example, both Explorers and the rest of the workforce were nearly neutral when asked if their companies have a flat organizational structure—Explorers averaged 4.3, the lowest value out of all organizational structure questions, while the rest of the workforce averaged 3.9. Additionally, the Explorers are more likely to report that their organizations have silos (4.4 versus 3.4). One possible explanation is that Explorers are more aware of silos as they try to quest and connect against the organizational design.

These results are not surprising considering the persistence of twentieth-century structures and practices in the current business environment. Many organizations today are still structured to maximize scalable efficiency; hierarchies and silos ensure control over processes in order to eliminate or reduce variance from plans and forecasts. Creative solutions to reduce silos and hierarchy could help further unleash the potential of Explorers, allowing them to more freely connect across the organization to identify learning and performance improvement opportunities. For some organizations, a reduction in silos and hierarchy may also elicit the dispositions of worker passion that have not yet emerged in certain individuals.

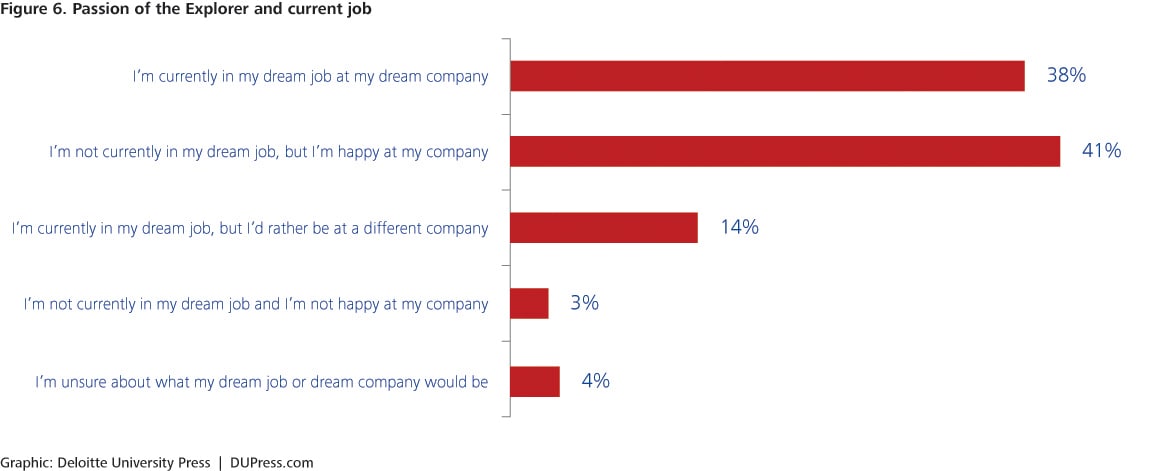

However, most Explorers are happy in their organizations. Seventy-nine percent of Explorers responded positively about their company, even if they are not currently in their dream role (see figure 6). This reflects the importance of the work environment in unleashing worker passion.

The passion of the Explorer and performance

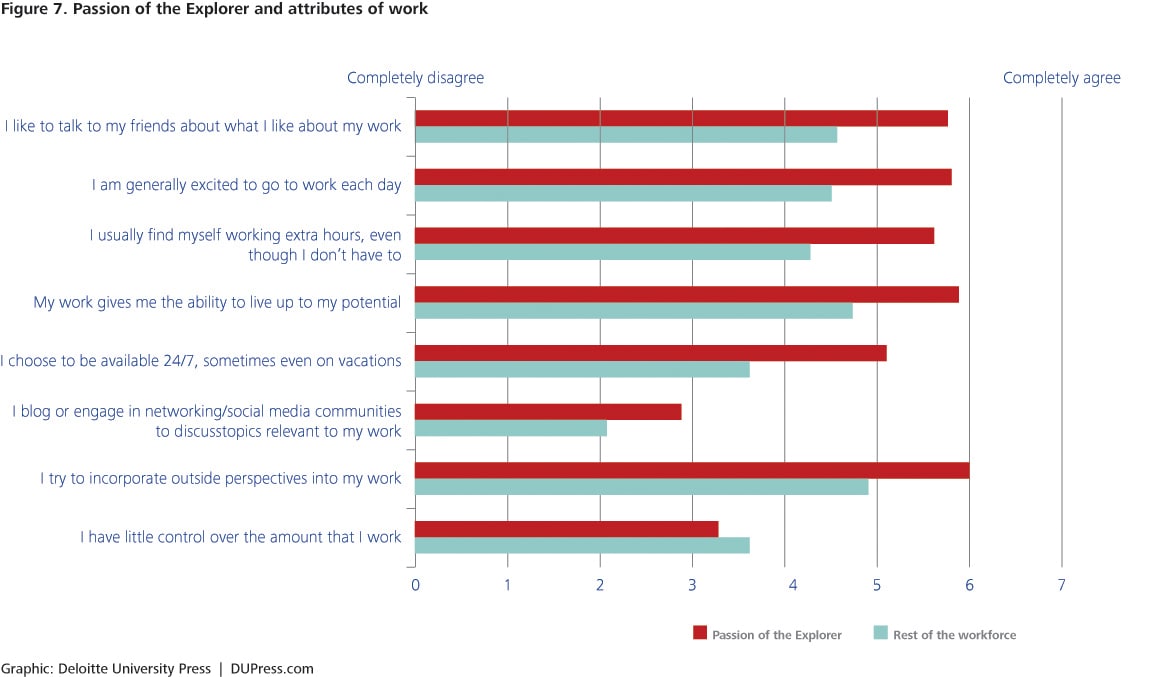

Explorers are concentrated in environments where they have opportunities to learn and make an impact. Explorers also tend to exhibit behaviors associated with high individual performance. Just like the athletes in extreme sports, passionate workers are committed to constant skill development. This individual performance improvement often advances organizational performance as a whole (see figure 7).

Individuals with the passion of the Explorer are more excited and willing to take on new tasks and challenges. When asked if work enables them to achieve their full potential, the average response for Explorers was 5.9 versus 4.7 for the rest of the workforce.

Explorers also leverage their ecosystems in order to advance their skills and identify new opportunities for their organizations. Explorers are more willing to participate in external groups or ecosystems in order to advance their learning. When asked if they try to incorporate outside perspectives into their work, the average response for the Explorers was 6.0 versus 4.9 for the rest of the workforce.

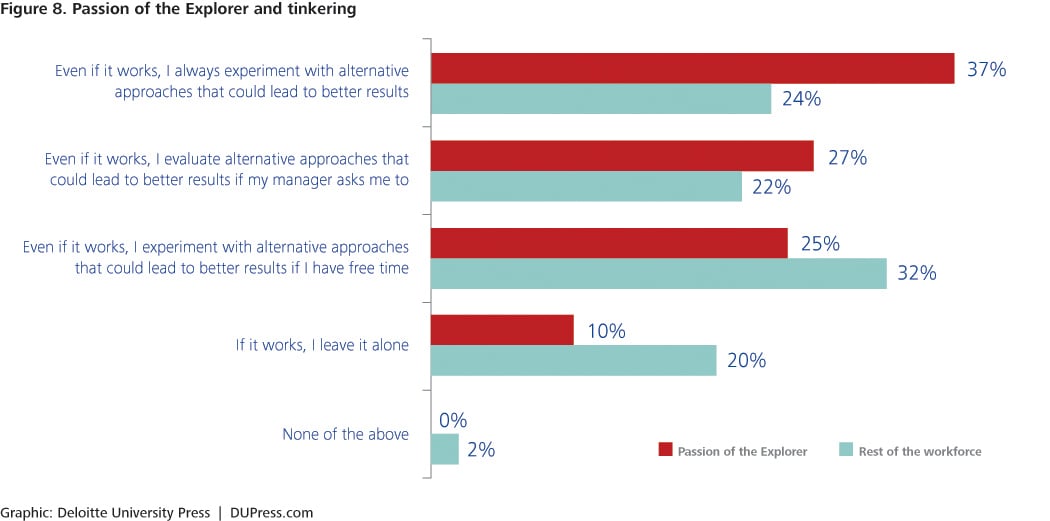

Interestingly, Explorers are more likely to tinker—37 percent report experimenting with alternative approaches, even if a product or process works, just to try out new ways of doing things (see figure 8). Only 24 percent of the rest of the workforce report such tinkering.

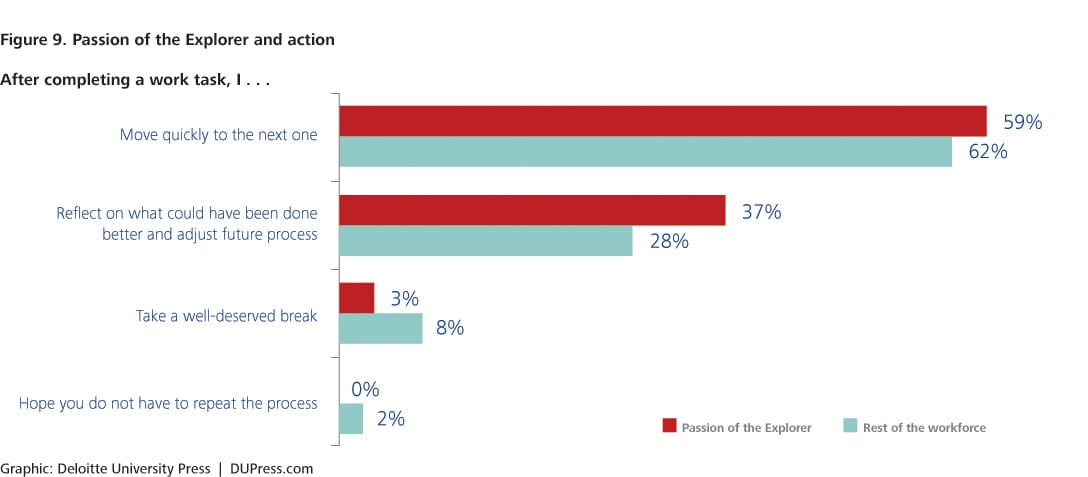

Finally, Explorers are more likely to reflect on recently completed tasks in order to internalize lessons learned and adjust future processes (37 percent versus 28 percent; see figure 9).

Faced with uncertainty and disruption, companies must rely on workers at all levels—from front line to management—to monitor signals of disruption, find opportunities, and quickly retool. The attributes associated with the passion of the Explorer are incredibly valuable to employers. Workers who view challenge and uncertainty as exciting adventures may better manage the stress of mounting performance pressures. The positivity, optimism, and willingness to go the extra mile coupled with exposure to new trends and developments that Explorers gain from participating in ecosystems could help their organizations navigate challenges and identify new opportunities. The tendencies to tinker and reflect are prerequisites for the experimentation and rapid prototyping of ideas essential for learning in a fast-moving environment.

The rest of the workforce

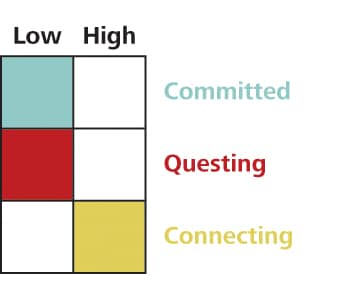

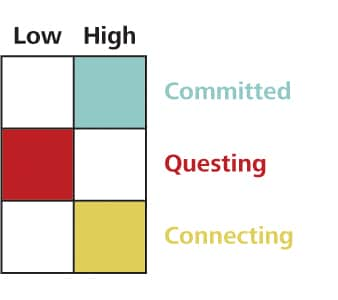

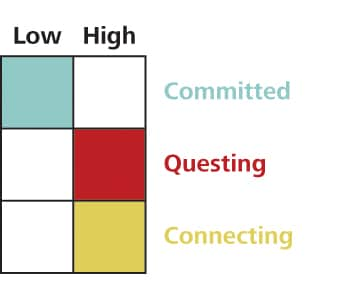

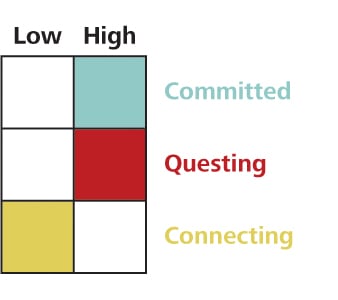

If the passion of the Explorer is so important for accelerating learning and performance improvement to help companies navigate the rapidly evolving world, what does it mean for the rest of the 89 percent of the US workforce? Does the rest of the workforce completely lack the attributes that characterize an Explorer? Fortunately, many individuals possess one or two of the attributes. We identified six other types of participants in the US workforce.

The Player

The Player

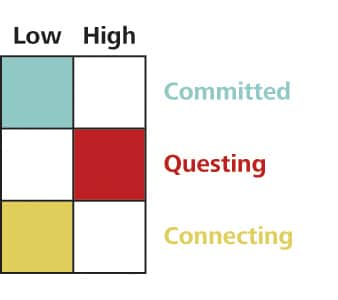

Description: The Player displays a strong Questing disposition but scores low on the Connecting disposition and Commitment to Domain.

Characteristics: The Player loves the challenge of work almost more than the work itself. Players get excited when faced with unexpected issues and actively seek challenges, embracing uncertainty as an adventure. They like to define their own job descriptions and responsibilities. Players, however, do not feel committed to a particular industry or domain. They also do not view interactions with their ecosystem as an opportunity to develop meaningful connections in order to advance their knowledge, and they are less inclined to reach out to others to solve a problem. Players may be very successful in a company that offers many new experiences but may fail to meet expectations in an organization that requires predictability and efficiency.

Concentration: 6.6 percent of the US workforce had the attributes of the Player.

The Loyalist

The Loyalist

Description: The Loyalist displays a strong Commitment to Domain but scores low on Questing and Connecting dispositions.

Characteristics: The Loyalist is focused on achieving a significant and increasing impact in the industry or domain in which they work. Loyalists are excited to go to work and believe work gives them the ability to live up to their potential. They believe their companies are making a difference in the ecosystem and that they are making a difference in their companies. Loyalists feel sufficiently rewarded for their contributions. Loyalists, however, do not like to try new tasks and do not proactively seek challenges at work. Also, Loyalists do not tend to reach out to others for help with problems.

Concentration: 8.7 percent of the US workforce had the characteristics of the Loyalist.

The Connector

The Connector

Description: The Connector displays a strong Connecting disposition but scores low on Questing and Commitment to Domain.

Characteristics: The Connector interacts and connects with others inside and outside of the organization in order to learn how best to solve immediate challenges. When faced with a challenge, Connectors reach out to others for help. Connectors, however, tend to avoid challenges outside their direct area of responsibility. To accelerate learning and performance improvement, the Connecting disposition is most effective when paired with other dispositions.

Concentration: 12.3 percent of the US workforce had the characteristics of the Connector.

The Performer

The Performer

Description: The Performer has a strong Commitment to Domain and Connecting disposition but scores low on the Questing disposition.

Characteristics: The Performer is a high-performer as long as the job function is well-defined. Performers thrive in the world of clearly defined processes, scalable efficiency, and approach work responsibilities with rigor. Performers typically love their work and are excited to go to work every day. They build networks to help solve immediate problems and aspire to achieve significant and increasing impact in their industry or domain. Performers, however, do not actively seek new challenges as a way to develop and learn more rapidly. Performers may not feel sufficiently rewarded for their efforts at work.

Concentration: 4.3 percent of the US workforce had the characteristics of the Performer.

The Learner

The Learner

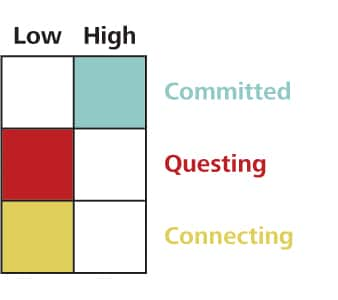

Description: The Learner displays strong Questing and Connecting dispositions but scores low on Commitment to Domain.

Characteristics: The Learner connects with others inside and outside of the organization in order to address challenges they cannot solve on their own. Learners have a strong desire to understand what has been done before and to reach beyond. They do not like their jobs defined in detail and instead prefer outlining their own responsibilities—and their own path to solve problems. Learners, however, do not have a strong commitment to an industry or domain and work to learn rather than work to make an impact on their particular domain.

Concentration: 8.4 percent of the US workforce had the characteristics of the Learner.

The Mad Scientist

The Mad Scientist

Description: The Mad Scientist displays a strong Commitment to Domain and Questing disposition, but scores low on the Connecting disposition.

Characteristics: Behind the passion of the Explorer, the characteristics of the Mad Scientist suggest the highest levels of performance. The Mad Scientist is highly dedicated and willing to work beyond regular hours. They are willing to make personal tradeoffs such as take lower compensation or move to a less desirable location in order to make an impact in their domain. Mad Scientists find meaning in their work and feel that work gives them the ability to live up to their potential. To Mad Scientists, it is very important that the job provides an opportunity to learn and develop new skills. Mad Scientists, however, are less likely to reach out to others for help solving an issue or learning how to address an unexpected problem.

Concentration: 5.1 percent of the US workforce had the characteristics of the Mad Scientist.

Combined, these six types of workers made up approximately 45 percent of the US workforce surveyed. We believe, however, that even workers who did not display the passion of the Explorer or any of the related attributes still have the potential to develop the skills and capabilities needed to navigate the world of constant disruption. Worker passion can be activated. Organizations have an opportunity to elicit and cultivate Commitment to Domain and the Questing and Connecting dispositions in all types of workers by redesigning their work environment—physical, virtual, and management practices. Deliberate cultivation by organizations would help individuals fulfill their potential and could help companies improve their performance.

Setting a context that activates passion

Similar to what Dave Hoover did at Obtiva, companies can foster passion in the workforce through a two-pronged approach. First, attract individuals who already possess the passion of the Explorer since these individuals have the greatest potential to thrive in an environment of constant change and ambiguity. Recruiting efforts should focus more on identifying dispositions and potential (future) and less on assessing candidates’ skills and credentials (history). Explorers motivate and energize, and bringing in individuals with the passion of the Explorer will likely help elicit similar dispositions in the rest of the workforce.

At the same time, given the apparent shortage of individuals with the passion of the Explorer, companies may not be able to attract and hire enough Explorers. Moreover, bringing Explorers into the organizations designed to “squelch” passion will likely not unleash the learning and performance improvement associated with passionate workers. Explorers will flee or become disillusioned in such environments. Instead, organizations should identify elements in the work environment that threaten or discourage passion and remove these barriers as quickly as possible.

Second, organizations should understand what types of workers they already have access to within their four walls—and beyond. If most workers already demonstrate one or two of the attributes required for the passion of the Explorer, organizations can redesign their work environment to encourage and cultivate the “missing” attribute. Organizations should ask themselves if they reward or punish failure and assess how they encourage, or discourage, workers to actively collaborate with the ecosystem on work projects. Additionally, companies should consider how to provide workers with more visibility and clarity into how each individual makes an impact on the company and the broader industry or domain.

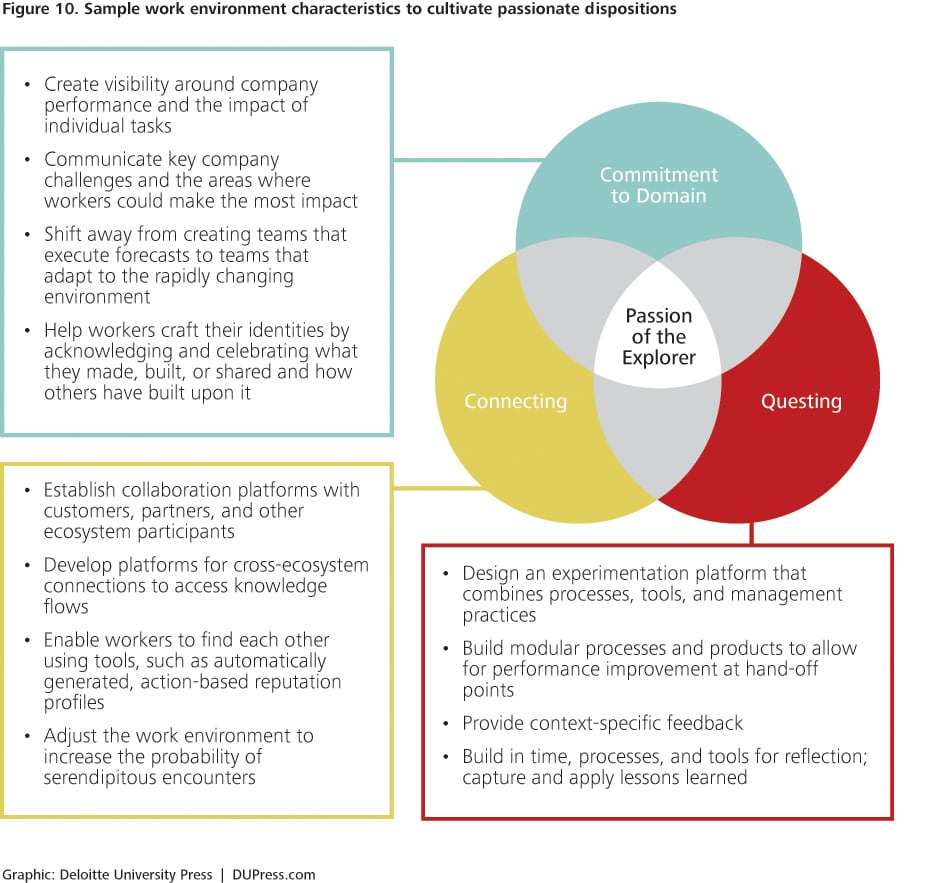

Organizations have an opportunity to redesign their work environments to ignite, amplify, and draw out worker passion within all of their workers—from management to the front line. Figure 10 suggests initial tactics for organizations to deploy to ensure that the work environment cultivates Commitment to Domain and the Questing and Connecting dispositions that make up the passion of the Explorer.

These tactics are a starting point, and organizations should consider additional design principles to create an environment that activates worker passion.21 More work remains to quantify the linkages between passion and performance and to track, over the long term, how changes in the work environment increase the prevalence of specific attributes across the workforce. What is clear is that, left unexamined, the mounting pressures of constant change combined with institutions designed for the twentieth century will likely continue to create stress, limit performance improvement, and leave workers neither empowered nor inspired to navigate the challenges faced by twenty-first-century organizations.

About the Center for the Edge

The Deloitte Center for the Edge conducts original research and develops substantive points of view for new corporate growth. The center, anchored in the Silicon Valley with teams in Europe and Australia, helps senior executives make sense of and profit from emerging opportunities on the edge of business and technology. Center leaders believe that what is created on the edge of the competitive landscape—in terms of technology, geography, demographics, markets—inevitably strikes at the very heart of a business. The Center for the Edge’s mission is to identify and explore emerging opportunities related to big shifts that are not yet on the senior management agenda, but ought to be. While Center leaders are focused on long-term trends and opportunities, they are equally focused on implications for near-term action, the day-to-day environment of executives.

Below the surface of current events, buried amid the latest headlines and competitive moves, executives are beginning to see the outlines of a new business landscape. Performance pressures are mounting. The old ways of doing things are generating diminishing returns. Companies are having harder time making money—and increasingly, their very survival is challenged. Executives must learn ways not only to do their jobs differently, but also to do them better. That, in part, requires understanding the broader changes to the operating environment:

- What is really driving intensifying competitive pressures?

- What long-term opportunities are available?

- What needs to be done today to change course?

Decoding the deep structure of this economic shift will allow executives to thrive in the face of intensifying competition and growing economic pressure. The good news is that the actions needed to address short-term economic conditions are also the best long-term measures to take advantage of the opportunities these challenges create.

For more information about the center’s unique perspective on these challenges, visit www.deloitte.com/centerforedge.

Contacts

Blythe Aronowitz

Chief of Staff,

Center for the Edge

Deloitte Services LP

+1 408 704 2483

baronowitz@deloitte.com

Wassili Bertoen

Managing Director,

Center for the Edge Europe

Deloitte Netherlands

+31 6 21272293

wbertoen@deloitte.nl

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.