CPG companies: Your next growth opportunity has a user name and password has been saved

CPG companies: Your next growth opportunity has a user name and password

10 May 2014

With the pace of digital commerce in packaged goods expected to accelerate, CPG companies should act now with a coordinated, systematic approach.

“CPG sales via e-commerce are a tremendous opportunity for retailers and CPG companies even if you only gain a few points of market share.”—Retail executive interviewee

Recent research suggests that many consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies may be less prepared to capitalize on e-commerce than they should be—or than many CPG executives would like to be. In a 2013 study comparing consumers’ and CPG executives’ views on e-commerce, fully 92 percent of CPG executive respondents agreed with the statement, “The e-commerce channel is a strategic sales channel for CPG companies.” Yet only 43 percent of these same executives thought that their company had a clear, well-understood digital commerce strategy, indicating a substantial gap between e-commerce’s perceived importance and CPG companies’ readiness to execute.1

Our first article on this research, Digital commerce in the supermarket aisle: Strategies for CPG brands, explored the questions “WHY is it important to take e-commerce seriously?” and “WHAT can CPG companies do to succeed in e-commerce?” As we shared the results with CPG executives, many asked us, “HOW can CPG companies become digital commerce leaders?” and “WHO are our e-commerce consumers?” This report presents further research that attempts to answer these questions.

About the study

The research described in this article encompassed two web-based surveys conducted in September 2013. One survey polled 43 US CPG industry executives and senior managers; the other, 2,040 adult US consumers. The research also included six CPG and retail executive interviews conducted in August and September 2013, and 14 case studies developed from secondary sources.

Sixty percent of the executive survey respondents worked at food companies, while the remaining executive respondents worked at beverage, household goods, or personal care companies. All executive respondents had at least some digital commerce experience; 65 percent spent at least 20 percent of their time on activities related to digital commerce (for example, e-commerce, digital marketing, mobile, and/or social media). A majority of the executive respondents (51 percent) were from large companies that recorded annual sales of more than $10 billion a year. Respondent roles and titles reflected a broad range of expertise in marketing/branding, sales, IT, and digital-related areas.

The consumer respondents, aged between 21 and 70 years, were screened to target consumers who were the primary shopper and food preparer in their household and had purchased a product online in the past six months. The majority of the consumer respondents (66 percent) were female. Forty-two percent reported an annual household income of less than $50,000, 36 percent earned between $50,000 and $99,999 annually, and 21 percent earned $100,000 or more annually.

The CPG and retail executives interviewed all had experience with digital commerce activities such as e-commerce, digital marketing, and social media. The interviews covered four topics: executives’ expectations for future CPG sales through digital commerce and their views on what could be driving e-commerce adoption; the challenges and opportunities for CPG companies in the e-commerce channel; the digital strategies CPG companies could adopt to better serve consumers in-store and online; and perceived consumer attitudes and behaviors related to online purchasing of food, beverages, household consumables, and personal care products. We included retail executives in our interviews because they have digital commerce experience across product categories and have also partnered with multiple CPG companies to grow e-commerce sales.

The e-commerce opportunity is real—but underestimated

“I don’t understand why rallying everyone to take this opportunity seriously is so difficult given the size of the e-commerce prize and the threat from e-commerce retailers.”—CPG executive interviewee

A decade after online shopping became mainstream, e-commerce for consumer packaged goods is finally arriving. While e-commerce is a small proportion of US retail sales,2 online retail growth is outpacing overall growth. According to the Retail Indicators Branch of the US Census Bureau, between 2000 and 2012, e-commerce sales across all retail channels (including non-CPG retail) grew by 19.1 percent annually, while overall sales only grew by an average of 3.2 percent annually.3 This growth rate for e-commerce is actually less than the growth expected among the online shoppers in our research, who said that they expected their online purchases of packaged goods to increase 67 percent in the next year and a cumulative 158 percent in three years. However, executives should consider that the historic e-commerce growth rate is helpful to conservatively size the market opportunity. More importantly, many online shoppers’ online purchases have expanded to include packaged goods such as food, beverage, personal care, and consumable household goods. As a group, online shoppers expect to make an even larger share of their CPG purchases online in future years.4

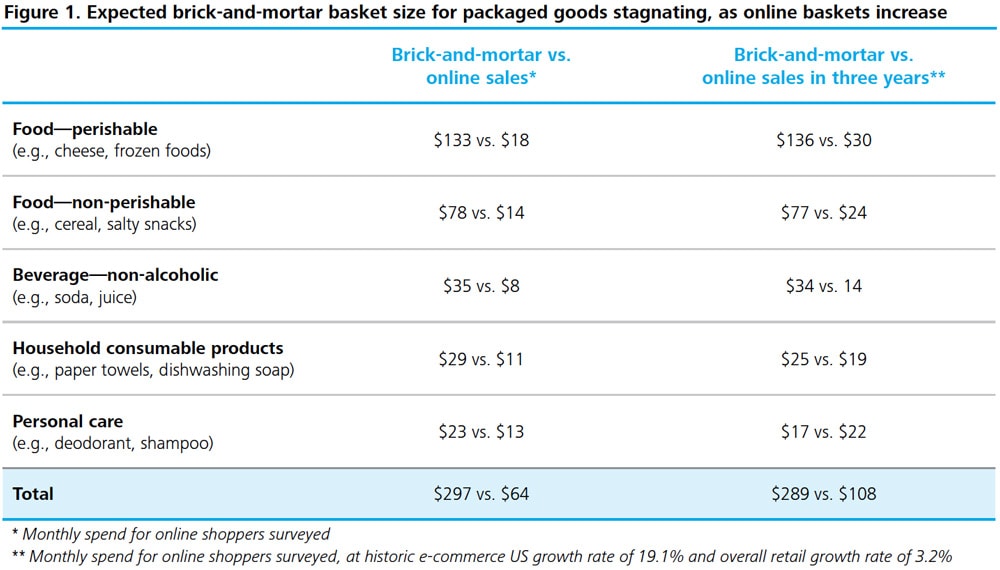

To put the e-commerce market opportunity in perspective, it is helpful to compare the monthly brick-and-mortar and online shopping baskets across five packaged goods categories among the primary online shoppers in our survey (figure 1). Our online shopper respondents estimated that their monthly brick-and-mortar basket size in these categories totaled $297, while their online basket size was $64. Applying the historical growth rates of retail online sales (19.1 percent) and overall retail sales (3.2 percent), we can project that these respondents’ brick-and-mortar purchases will decline slightly to $289 per month in three years, while their online basket size would increase from $64 to $108 per month (figure 1). Said another way, while brick-and-mortar sales stagnate, online packaged goods sales could increase nearly 70 percent. For a billion-dollar CPG brand, this could amount to increased online sales of $122 million in the next three years.

However, our results suggest that, though most CPG executives understand that a shift to online is happening, many may be underestimating the size of the opportunity. With respect to both overall growth and the opportunity to make incremental sales, we found major disconnects between what consumers are planning for in e-commerce versus what companies are prepared for:

- While the e-commerce opportunity is evident, CPG companies appear to be somewhat slow in taking advantage of it. This is not for lack of a general awareness that the opportunity exists: Most CPG executives believe that digital commerce impacts the entire path to purchase, from brand awareness (90 percent of CPG executives surveyed rate this as very important or important) and product trials/initial purchases (86 percent) to driving repeat purchases (93 percent) and reconnecting with lapsed consumers (88 percent).

- The online sales growth in the CPG category expected by shoppers exceeds CPG executives’ expectations. The CPG executives in our survey expected to see 35 percent growth in online sales over one year and 76 percent growth over three years. On the other hand, consumers who were already purchasing CPG products online expected to buy 67 percent more in a year’s time and 158 percent more in three years.

- CPG executives are underestimating the potential for e-commerce to drive completely new or incremental sales. CPG executives appear to be underestimating the incremental sales opportunity from e-commerce and overestimating the cannibalization effect of online channels. The CPG executive respondents to our survey felt that only 2 percent of the past year’s growth in e-commerce revenue came from completely new sales. Surveyed consumers, however, stated that 10 percent of their online food, household consumable, and personal care purchases over the past year had been completely new—that is, purchases that they would not have made at all had the online purchasing option not been available.

As a result of these disconnects, many CPG companies are not moving fast enough. A “wait and see” approach to e-commerce could mean missing out on a way to secure a competitive advantage.

Dipping one’s toes or fully immersed?

The CPG executives we spoke with and surveyed fall into two broad categories. In the first category are executives that work for CPG companies that have not started building e-commerce capabilities. These executives are asking: “How do I get going?” In the second category are executives whose companies are already moving down the path of building digital commerce capabilities. These executives are asking: “How do I know I have not made a mistake?” In both categories, executives want to avoid making wrong turns, revisiting ground already covered, or even supporting conflicting tactics. They also want assurance that they are addressing tactics in the right sequence and investing in the right areas. This leads to a fundamental question for CPG leaders as they seek to embed digital capabilities within their organizations: “Are we just dipping our toes into the e-commerce opportunity or are we fully immersed?”

CPG companies could see benefits from e-commerce if they are “fully immersed” and vigorously pursue the opportunity. Organizations that are overly cautious in experimenting with e-commerce risk not only upsetting traditional brick-and-mortar retailers, but also confusing consumers. Tentative e-commerce efforts that increase channel conflict could accidentally cannibalize existing sales and reduce a company’s pricing power instead of deliberately driving incremental growth. CPG companies that are slow to commit could therefore not just be missing out on market opportunity, but actually harming themselves.

“HOW can CPG companies become digital commerce leaders?”

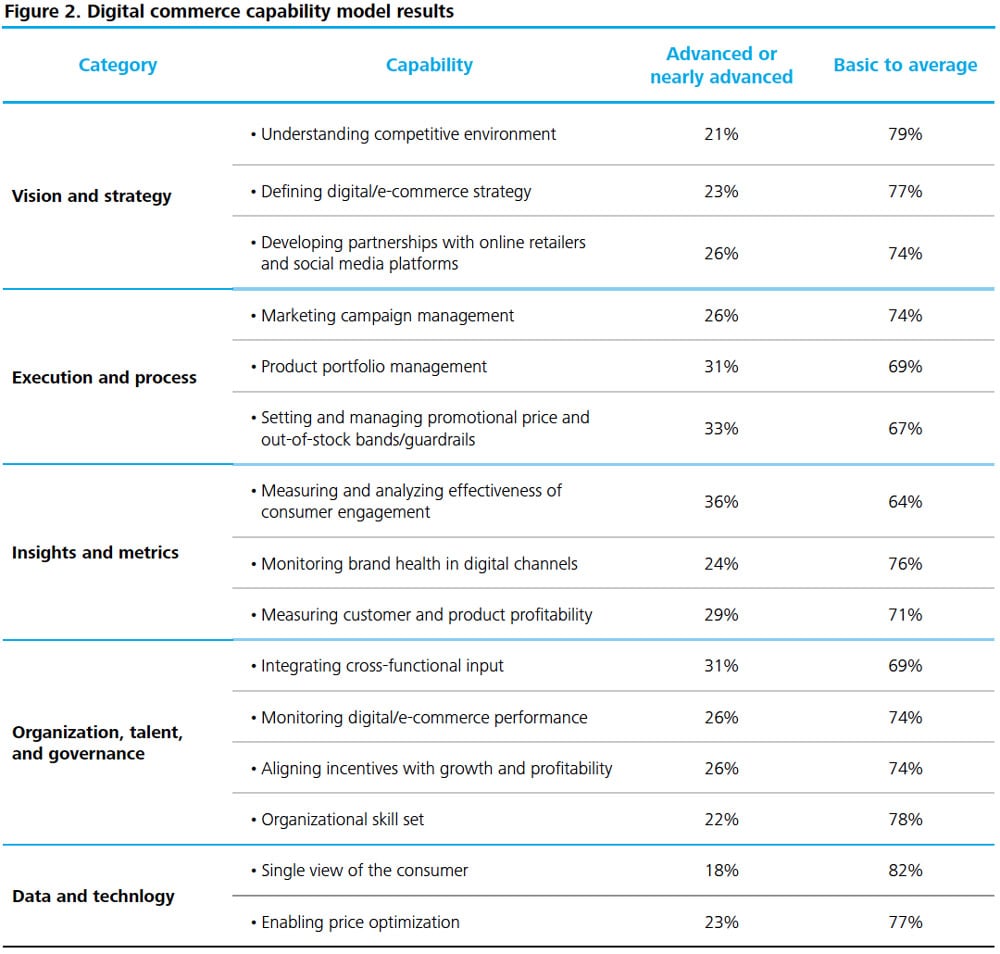

Many of the CPG executives we surveyed felt that their companies were weak in a number of specific capabilities needed to succeed in e-commerce. Across the 15 distinct capabilities that comprise our digital commerce capability model for CPG companies,5 our CPG executive respondents self-assessed their companies as “basic” to “average” more than half the time. That is, across the 15 attributes, an average of 74 percent of respondents rated their company as “basic” to “average,” while only 26 percent rated their employer as “advanced” or “nearly advanced”—revealing a stark shortfall in capabilities (figure 2). These results, along with our executive interviews, shed some light on why succeeding in digital commerce can be so difficult.

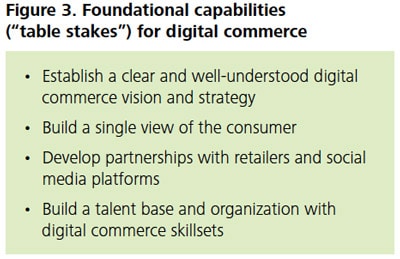

Previously, we published our view of several foundational capabilities, or “table stakes,” for succeeding in digital commerce (figure 3). Our interviews with CPG executives show that, while many appreciated the importance of the table stakes, they faced several common difficulties in putting them in place:

- Gaining broad agreement across the organization on the importance of e-commerce

- Coordinating digital activities across the organization

- Reaching agreement on the best sequence to build digital capabilities

Table stake 1: Establish a clear and well-understood digital commerce vision and strategy

Challenge: Aligning decision making with the digital commerce strategy across the entire organization

“While I understand our digital commerce strategy, important strategic decisions are still being made independently by account teams, operations, and IT that are counter to what we are trying to accomplish.” —CPG marketing executive interviewee

The natural first step for CPG companies building digital commerce capabilities is to set a strategy and vision. But while many CPG companies may have a strategy, for most it is not comprehensive enough to drive alignment and support rapid decision making. Only 23 percent of the CPG executives we surveyed consider their digital commerce strategy to be “advanced” or “nearly advanced.”

To create a unified digital strategy, CPG companies should begin with the fundamental decisions of setting their digital commerce objectives for each brand and product category (figure 4). They should then aim to clearly articulate these decisions in a way that is not only aligned across multiple functions (including marketing, sales, finance, distribution, and IT), but that also cascades to each function. For example, explicit guidelines should be put in place about what products should be available online, at what prices, and at what promotional level. Target consumer segments should be identified and customized brand messages created. Furthermore, while e-commerce should be viewed as a distinct channel, planning for the e-commerce channel should be integrated with other channels—and receive dedicated focus from leadership. Customer experience standards should be clearly defined and drive decisions around business demand planning (e.g., product availability).

Challenge: Developing an integrated product and pricing strategy across e-commerce and brick-and-mortar channels

“Increased online pricing visibility has resulted in a perfect market where you lose deals for a penny. We seem like spectators to the dynamic pricing at e-commerce retailers for our products.” —CPG executive interviewee

As consumers have gained more visibility to relative assortments and pricing across brick-and-mortar and online stores, channel-specific product strategy and pricing strategy have become inextricably linked. Unfortunately, both are areas in which many of our CPG executive respondents felt their companies fell short. Only 31 percent self-assessed their company as advanced or nearly advanced in product portfolio management; even fewer (23 percent) self-assessed their company as advanced or nearly advanced in price optimization.

With respect to product portfolio management, CPG companies without concerted channel-specific efforts risk inefficiency if they lack a well-thought-out cross-channel product strategy or assume that e-commerce is all about price. Executives should aim for visibility into what products are currently available online and at what price. This requires a good understanding of which retailers and distributors are currently selling online as well as the key drivers of their strategies (e.g., sell full product portfolio at full price, liquidate obsolete stock at discounted prices). Furthermore, CPG companies should develop clearly defined guidelines on what products, brands, and categories should be available online and across channels. This means influencing the assortment and pricing among both online-only retailers and the online presence of traditional brick-and-mortar retailers.

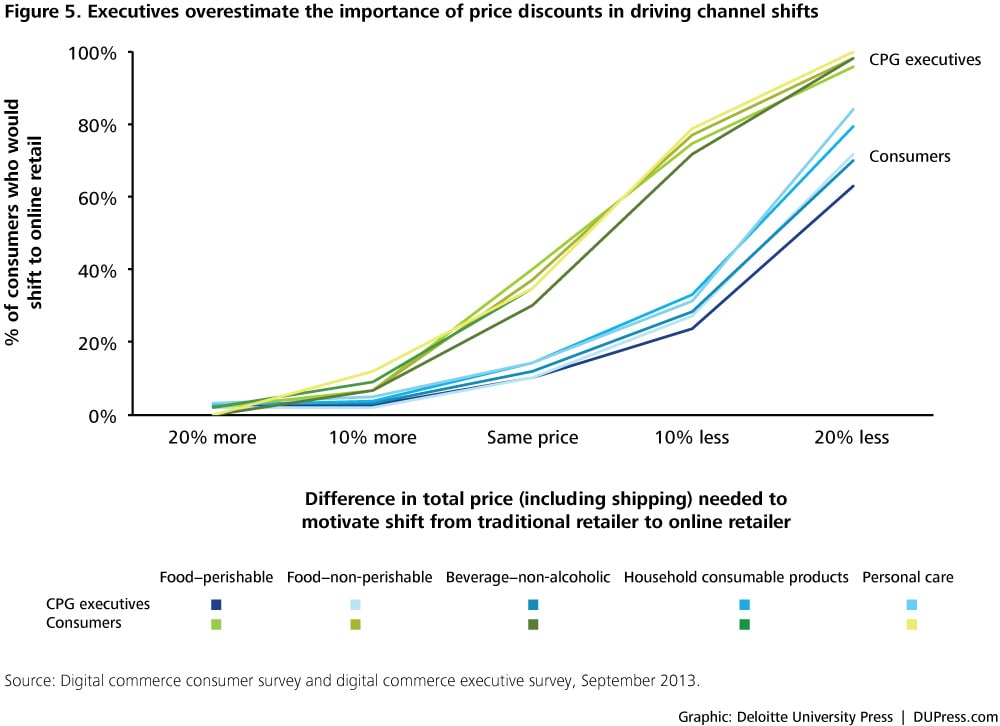

With respect to pricing, executives should beware of overestimating the impact of pricing discounts on the propensity for consumers to shift to the online channel, which could result in diluted margins and increased channel conflict. We asked the executive and consumer respondents in our survey to estimate the total price difference (including shipping) that they believed would prompt consumers to shift purchases to an online retailer (see figure 5). Across categories, executives anticipated that 76 percent of consumers would shift their purchases to an online retailer at a price discount of 10 percent. However, only 29 percent of consumers said that they would shift to an online retailer at a 10 percent price discount. This indicates that CPG companies should focus, not only on price discounts, but on having a variety of price and non-price-related levers to attract consumers to the online channel. In addition, understanding specific pricing sensitivity will be critical to managing margin.

CPG companies, like leading retailers, may wish to develop automated tools to calculate demand-driven online prices in real time. Furthermore, sophisticated, dynamic pricing can be used to determine the financial impact of online price changes and expected competitor responses. While cross-channel price setting is a challenge, most executives seem comfortable with setting promotional pricing bands, a strategy that can prove effective for the online channel. This requires companies to set both online price bands and out-of-stock levels along multiple dimensions based on growth, share, and profitability targets. Compliance against bands and granting exceptions to deviate from promotional, pricing, and out-of stock guardrails should be managed on a portfolio basis.

Table stake 2: Build a single view of the consumer

Challenge: Building an authoritative and accessible single view of the consumer to understand consumer attitudes and behaviors and enhance the consumer experience across channels

“The greatest challenge we face in the e-commerce channel is accessing a complete view of the consumer from across all the different consumer touch points.” —CPG executive interviewee

Only 18 percent of the CPG executives we surveyed rated their employer as advanced or nearly advanced in the data and technology used to create a single view of consumer purchasing behaviors and attitudes. This therefore, represents a substantial opportunity for improvement among the majority of CPG companies, where having a single view of the consumer can drive benefits in all channels.

Ideally, brand managers should have the ability to track and easily access consumer information in one single view (or database) that includes demographics, past purchases, and coupon redemption patterns. This single database should aggregate information from sources including the brand website, social media sites, and retailer store data. But getting to such a unified view is about much more than the technology that collects and stores the data. It is also about having effective processes for identifying the most important data points, collecting the data across the entire path to purchase, and linking the data to create consumer profiles and build out target consumer segments. CPG companies have been slow to develop a full lifecycle view of the evolving consumer experience from pre-sale touch points (e.g., building awareness, conducting research) to post-purchase interactions (e.g., receiving the product, using the product, servicing the product, and engaging with the brand and other users). With such data, CPG companies can work to characterize consumer attitudes and use that information to enhance the consumer experience. They can then pull multiple levers (e.g., promotions, product offerings, pricing) to entice consumers and to predict the effectiveness of promotions.

Challenge: Measuring and analyzing the effectiveness of consumer engagement across channels

“We are getting better at measuring targeted marketing and trade promotion ROI with a single retailer; however, we are a long way away from understanding the cross-channel impact. For example, to what extent are e-commerce promotions and sales impacting club and grocery sales?”—CPG executive interviewee

While a relatively high 36 percent of the executives we surveyed rated their ability to measure and analyze the effectiveness of their consumer engagement efforts as “advanced” or “nearly advanced,” our executive interviews revealed that this capability is much stronger in narrowly targeted campaigns than with cross-channel digital efforts. For example, many of the executives we spoke with felt that they were able to assess the performance of past campaigns and feed insights into the development of future programs. However, they were less confident in their ability to understand the impact of digital engagement across channels.

Leading companies will strive to aggregate consumer engagement and marketing campaign data to develop consumer insights across channels and retailers. Further, digital marketing should be part of a holistic marketing plan that is in sync with brand marketing, trade marketing, and direct mail programs. The mix of national, regional, and personalized campaigns should complement each other.

Table stake 3: Develop partnerships with retailers and social media platforms

Challenge: Defining and executing upon a mutual value proposition for CPG and e-commerce retailers

“Some [CPG companies] want to move rapidly and are trying to increase their understanding of the rapid changes occurring related to e-commerce. However, most are moving cautiously due to concerns about channel conflict and not wanting to alienate existing retail customers.” —CPG executive interviewee

Only 26 percent of surveyed CPG executives rated their ability to develop partnerships with online retailers and social media platforms as “advanced” or “nearly advanced.” One CPG executive we spoke with acknowledged that the organization had figured out target customer segments and retailer-specific product offerings for the club and dollar channel, but that it was still trying to develop a unique value proposition for the e-commerce channel’s retailers and consumers.

CPG companies should segment online retailers based on their importance and alignment with target consumer segments. For priority retailers, CPG companies should assign key account teams guided by clear long-term objectives, targets, and expectations that are well understood across the functions, including sales, marketing, and operations. To create a win-win proposition for both themselves and the retailer, CPG companies should plan joint marketing campaigns, pricing strategies, promotional objectives, and product offerings with their selected key online retailers. The win-win collaboration should aim to expand category sales, build brand strength, align with the retailer’s supply chain and cost structure, and uniquely serve targeted consumer segments. For example, CPG companies may want to invest in developing shipper-friendly packaging that is more resistant to weather, spill-proof, and sized for efficient shipping.

It is important that CPG companies be able to communicate the mutual benefits of collaboration to their retail customers. For example, when brick-and-mortar retailers challenge CPG companies with the claim that their online efforts are cannibalizing sales, CPG executives can show retailers the countering data to demonstrate otherwise: that (for example) most online sales are incremental sales that would have been lost if the preferred brand or SKU were not available in the store. Often, online efforts may actually help build brand loyalty, which ultimately also benefits the retailer.

Online efforts with retailers should also consider the ever-expanding role and changing digital ecosystem of social platforms and technologies. Just as retailers often serve as an intermediary between brands and consumers, digital social platforms can be an important interaction point. Most (79 percent) of the CPG executives we surveyed rated social referral (e.g., social following to drive engagement, social amplification of promotions or brand offers, social shopping) as “very important” or “important” in influencing consumer behavior. Furthermore, 70 percent of CPG executives surveyed expect to increase investment in social referral in the next year. Similarly, most (68 percent) of the CPG executives surveyed view in-store shopper behavior and engagement technology (e.g., in-store engagement, consumer-enabled in-store tracking, retailer-enabled in-store tracking) as “very important” or “important” in influencing consumer behavior. Seventy-four percent plan to invest more in these capabilities within the next year.

Table stake 4: Build a talent base and organization with digital commerce skill sets

Challenge: Attracting, developing, and retaining digital-savvy talent across the organization

“Our greatest challenge is finding talented people with digital commerce expertise.”—CPG executive interviewee

Only 22 percent of the CPG executives we surveyed rated their company as “advanced” or “nearly advanced” in terms of their company’s digital skill sets. However, there is hope. CPG companies do not have to start from scratch to build digital commerce capabilities. In many cases, the needed skills may be transferable from other channel or account teams. In other cases, partnerships with retailers and digital agencies can close the digital capability gap. Indeed, some CPG companies that started out by trying to hire the “perfect” digital expert—and were frustrated in the attempt—have found that partnering with a digital agency or retailer to help develop the talent internally is a faster approach.

CPG companies should take care to assign people to the digital channel who have the right skill sets to maintain a broader understanding of the cross-channel shopper. The team that designs and executes digital commerce strategies should have experience not just in digital media and e-commerce, but also in traditional marketing, sales, supply chain, and account management. In addition, it is important to think carefully about how to align employee incentives—which are primarily growth- and profitability-based incentives for the current year—with the longer-term opportunity in digital commerce. This is an area where many of our executive respondents felt their companies fell short; only 26 percent of the CPG executives we surveyed rated their companies as “advanced” or “nearly advanced” in strategically aligning performance measurement, compensation, and incentives with growth and profit objectives. One retail executive we interviewed perceived this lack of alignment in his interactions with CPG companies: “I can understand that CPG companies continue to focus on the large brick-and-mortar retailers because they represent a majority of their business. However, unless they better incent their account teams to invest more time in the e-commerce channel, they risk losing out on future growth.”

Only 26 percent of surveyed CPG executives rated their ability to develop partnerships with online retailers and social media platforms as “advanced” or “nearly advanced.”

“WHO are our e-commerce customers?”

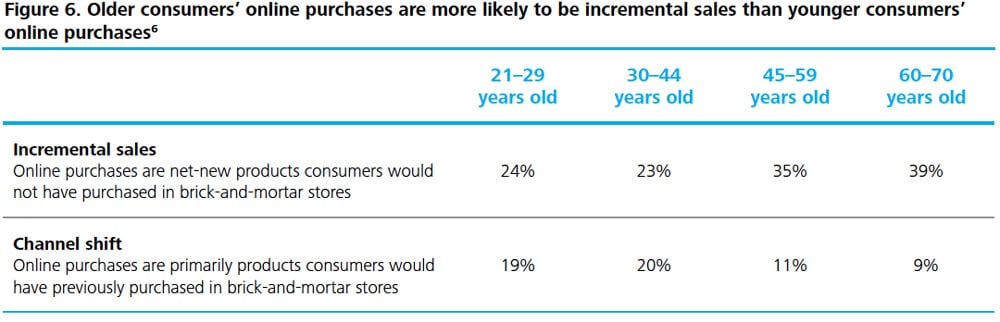

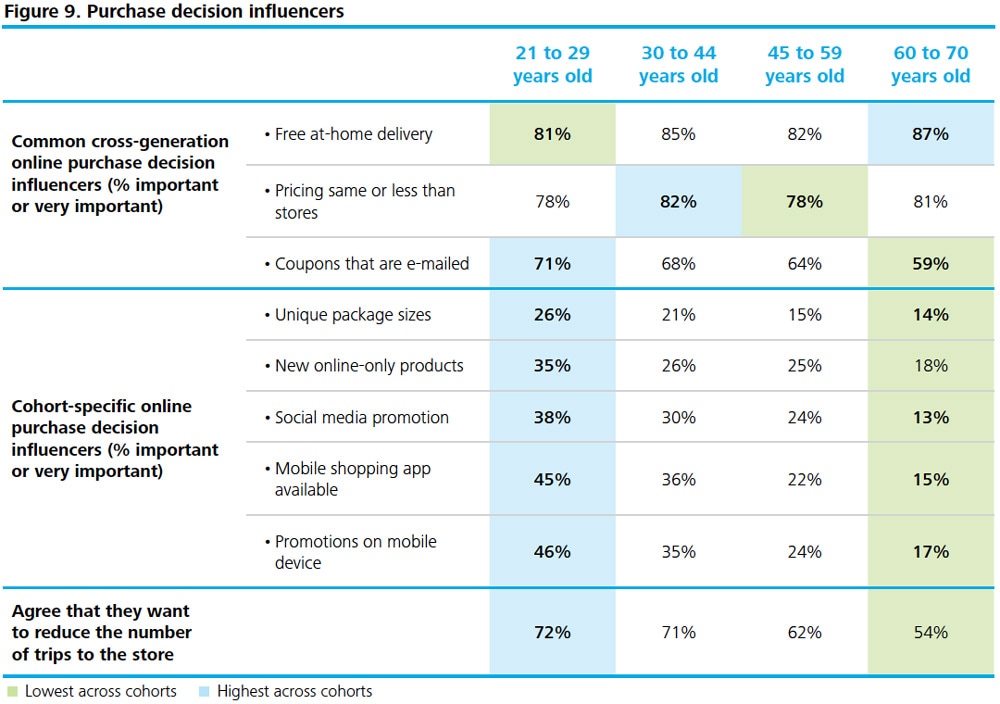

We turn now to the question, “WHO are the online shoppers that CPG companies should be targeting?” Contrary to what might be assumed, our research shows that the e-commerce opportunity for CPG companies extends across all generations, not just to younger consumers. The next three years are likely to witness rapid adoption of online CPG purchases by consumers of all ages. Among the respondents to our survey, consumers aged 30–44 years expect the highest growth (178 percent) in online CPG purchases in the next three years, ahead of the expectations of the 60–70 age group (143 percent), the 45–59 age group (152 percent), and even the 21–29 age group (150 percent). Furthermore, the likelihood of digital commerce generating incremental sales instead of just channel shifts is much higher for older consumers (see figure 6).

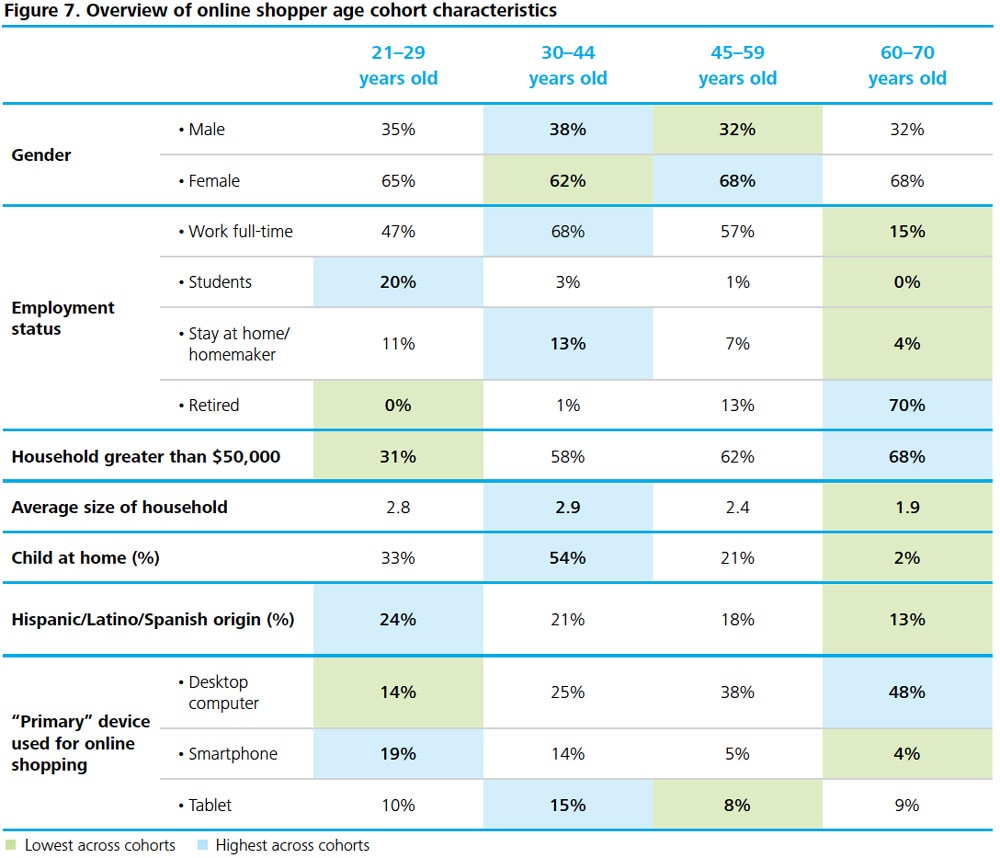

Executives should consider that the adoption of online CPG purchases will be shaped by the distinct personalities of each age group. In our consumer survey of online shoppers, we looked at four distinct segments of online shoppers classified by age. For each age cohort, we sought to understand the drivers of online purchasing, the factors that hinder e-commerce growth, and the influence of technology—especially the devices typically used by consumers for online shopping. These results can inform an initial strategy for how to approach online shoppers in various demographics. As CPG companies and retailers make investments in data and analytics to better understand consumer attitudes and behaviors, their ability to develop a deeper understanding of the consumer preferences of different age groups can facilitate more targeted consumer acquisition and retention efforts.

60–70-year-old online shoppers

“I am getting older and the idea of having the convenience of ordering online for pickup or delivery, if cost-effective, appeals to me.” —Survey respondent, 60–70 years old

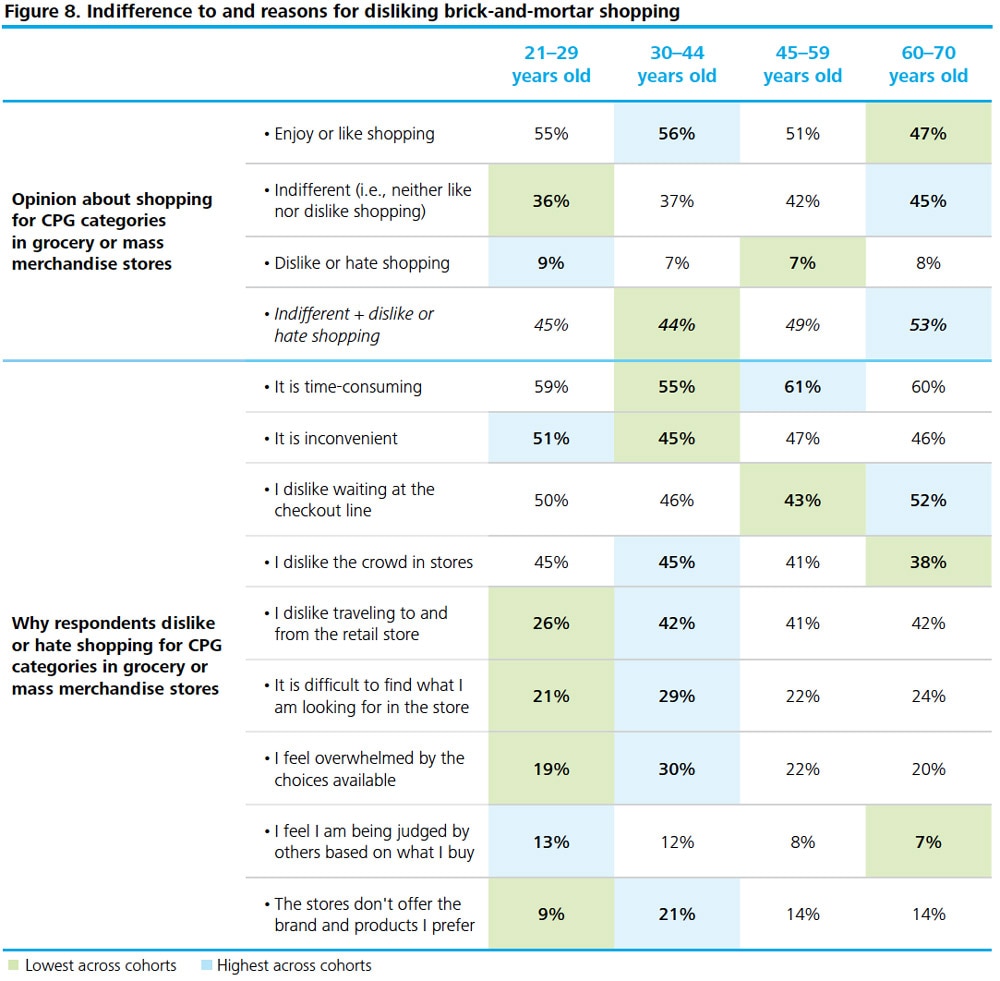

The 60–70-year-old online shopper is typically the most financially well-off of the four age groups we studied. Most are retired, married, and empty nesters. The majority own smartphones, but very few use them for online shopping; in our survey, 48 percent of respondents in this cohort said that they used a desktop computer as their “primary” device for online shopping. More than half (53 percent) of respondents of this age group said that they were indifferent to or disliked in-store grocery shopping, a higher percentage than in any of the other age groups. In addition, more than 40 percent of those who disliked in-store grocery shopping said that they disliked traveling to physical stores, though less than half said that they found shopping inconvenient.

As these older consumers age and their physical mobility declines, the convenience of at-home delivery of CPG products seems likely to emerge as an important decision attribute. While lagging other generations in technology usage today, these older consumers indicate an increasing openness to online ordering and delivery. Appealing to this segment means understanding that online purchases may begin as incremental purchases of products that are difficult to find in brick-and-mortar stores and expanding over time to products they would have bought in the grocery or mass merchandise channels.

45–59-year-old online shoppers

“In the event my mobility became an issue, then I would probably do more online shopping for food and beverage and household consumables.”—Survey respondent, 45–59 years old

The 45–59-year-old online shopper in our survey typically works full-time and is actively planning for retirement. Most have an annual household income greater than $50,000. Most are married, 21 percent have a child at home, and 36 percent live in households with three or more people. Like their older counterparts, the majority of 45–59-year-old online shoppers own smartphones, but are unlikely to use them for online shopping. About 49 percent said that they were indifferent to or disliked in-store grocery shopping. Similar to older shoppers, more than 40 percent of the 45–59-year-old cohort who disliked in-store grocery shopping said that they disliked traveling to stores, and less than half said that they found shopping inconvenient.

As with the 60–70-year-old shopper, appealing to this cohort begins with convenience of ordering and delivery. Targeting 45–59-year-old online shoppers means understanding that they are more tech-savvy (e.g., more likely to place importance on mobile coupons and apps) than the older cohort. Interestingly, older online consumers surveyed (both 45–59-year-old and 60–70-year-old shoppers) are more likely than other cohorts to connect with CPG manufacturers online to learn about products, indicating an opportunity for CPG companies to step up their efforts to provide product information that assists with the buying decision.

30–44-year-old online shoppers

“I hate having to wander up and down aisles in a supermarket trying to find what I want. It’s tiring and aggravating. When I shop online, all I have to do is enter what I want into a search box and voilà! It’s usually at the top of the search results. It doesn’t get much easier than that!”—Survey respondent, 30–44 years old

The 30–44-year-old online shopper in our survey is likely to be working full-time, with an annual household income of more than $50,000. More than half are married, and family size is at its peak: More than 50 percent have a child at home, and 55 percent are in households with three or more people. In our survey, 82 percent of this cohort owned smartphones, and 14 percent said that they use smartphones the most for online shopping. About 44 percent are indifferent to or dislike in-store grocery shopping. Less than 50 percent of those who dislike in-store grocery shopping find shopping inconvenient, but more than 40 percent dislike traveling to stores.

The most noticeable characteristic of the 30–44-year-old online shoppers in our survey was that they seemed to be somewhat brand loyal to save time while shopping. Thirty percent said that they felt overwhelmed by the choices available in-store, 29 percent said that they found it difficult to find what they are looking for, and 21 percent said that they disliked shopping because stores do not offer their preferred brands/products. To appeal to these often time-starved consumers, supporting a convenient shopping experience and offering the right product assortment (e.g., not too many offerings, but not too few) are critical.

21–29-year-old online shoppers

“[Online shopping] is more convenient. It seems like such a chore to go buy some of the household consumable items in the store. It is much easier and feels less like running an errand if I get it delivered. Trying new items I see online (in advertisements or on social media sites) leads to me purchasing them right away from a website.” —Survey respondent, 21–29 years old

The 21–29-year-old online shopper in our survey has just recently entered the workforce, or may even still be a student. Few have an annual household income over $50,000. Almost half are single, with the balance living as couples or married. The size of the family is expanding: 33 percent have a child at home, and 53 percent are in households with three or more people. This cohort was the most likely to use smartphones for online shopping: 89 percent owned a smartphone, and 19 percent said that they used smartphones the most for online shopping. Forty-five percent are indifferent to or dislike in-store grocery shopping. Among those who dislike grocery shopping, 51 percent consider in-store shopping inconvenient—yet, interestingly, only 26 percent dislike traveling to stores, the lowest percentage by far among any of the age groups.

To appeal to this cohort, CPG companies should embrace their evolving preferences and enduring dislikes. For example, while not many younger shoppers dislike traveling to stores, many dislike the in-store experience enough to want to reduce the number of trips to stores compared to older consumers. This cohort has a relatively higher dislike of key elements of the in-store experience, such as crowds and waiting in line. Not only are they more likely to want to buy more packaged goods online, but they also want one source for all online purchases. Furthermore, compared to older consumers, younger consumers are more likely expect same-day or next-day delivery.

Shifting the balance of power

What does e-commerce success look like for CPG companies? It begins with agreement across the organization on the importance of digital commerce. It means not only coordinating digital activities across the organization, but also reaching agreement on the best sequence to build digital capabilities. It means building a single view of the e-commerce consumer across channels. And it means tailoring the company’s e-commerce strategy to accommodate the needs and behaviors of distinct customer segments based on age and other distinguishing attributes.

With online shopping, executives should consider that CPG companies have the opportunity to potentially shift the balance of power with brick-and-mortar retailers in their own favor. Today, brick-and-mortar retailers often have the upper hand over CPG companies (e.g., retailers have the ability to preferentially allocate shelf space to store brands), and the cost structure for CPG companies to serve retailers is often high (e.g., due to slotting fees, promotions, distribution, and retailer-specific SKUs). However, in the online world, CPG companies have an advantage over e-commerce retailers, who need CPG companies’ brands to entice consumers into shopping online. CPG companies should act now to gain better control over the cost structure of serving the e-commerce channel. If executed well, a CPG company’s e-commerce strategy holds the potential to make the online channel cost favorable, not just now, but into the future.

Companies that want to win in digital commerce will not wait for the market to get bigger, and they will not experiment in an ad hoc fashion. Rather, they should act now with a coordinated, systematic approach. With the pace of digital commerce in packaged goods expected to accelerate, CPG companies do not have the luxury of a shallow learning curve. The stakes are too high.

Deloitte’s consumer products practice helps CPG and other consumer products businesses address issues in areas including consumer behavior and the growth of private label brands, food and product safety, M&A within the industry, supply chain effectiveness, and talent management. We serve companies operating in apparel and footwear, food and beverage/food processing, and personal and household goods. Contact the authors for more information or learn more about our consumer products practice on www.deloitte.com.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.