Improving care and creating efficiencies Are physicians ready to embrace digital technologies now?

13 minute read

03 September 2020

Bill Fera United States

Bill Fera United States Brian Doty United States

Brian Doty United States Wendy Gerhardt United States

Wendy Gerhardt United States Natasha Elsner United States

Natasha Elsner United States

Emerging digital technologies, such as robotic process automation and artificial intelligence, hold great promise to deliver better quality care at a lower cost. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians experienced the rapid adoption of these new tools … and their benefits. How might health care organizations further realize their potential?

Executive summary

Emerging digital technologies, such as robotic process automation and artificial intelligence (AI), hold a great deal of promise to improve health care—better quality at a lower cost. Despite often negative past experience with electronic health records (EHRs),1 practicing physicians are generally hopeful that new technologies will make their work more efficient.

Our nationally representative survey of 680 primary care and specialty US physicians, fielded in January and February 2020, found that:

- Seventy-three percent say that saving time and resources is expected to be the No.1 benefit of AI for the industry

- Seventy-seven percent say that the biggest impact on their practices from automation would be in terms of efficiency

- Seventy-six percent see the most opportunity for automation with coding for billing and reporting and with prior authorization requirements

- Fifty-four percent say that they would increase their use and support of AI-driven solutions if those solutions are shown to improve efficiencies and 52% would do so if they are shown to improve quality

Physicians do have concerns with emerging digital technologies, including the impact on patients and the reliability and accuracy of the technologies:

- Forty-four percent are concerned about the negative impact on the physician-patient relationship, 42% are concerned about the increase in medical liability risk, and 40% are concerned about the negative impact on patient engagement from automation

- Sixty-nine percent ask who is liable when the technology makes a mistake

Learn more

Explore the health care collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

The COVID-19 pandemic caused technology adoption to rapidly accelerate as organizations implemented new digital tools, often taking risks with unproven technologies.2 Physicians, in turn, quickly learned and incorporated the new tools in their practice, including virtual visits, remote monitoring, and analytics. Now that physicians have experience with the rapid adoption of these new tools and have seen their benefits, organizations are poised to realize the potential of emerging technologies such as AI and automation.

Building from this momentum, new initiatives should capitalize on value and consider how digital technologies can improve efficiency and workflow and not negatively impact quality and patient relationships. Involving key physicians and physician leaders in the process, communicating the benefits, prioritizing efficiencies, and ensuring minimal disruption to physician workflow should alleviate these concerns.

Where should investments start? Executives should consider starting with low-hanging fruit—digital technologies that improve upon mundane tasks for physicians or activities that happen behind the scenes. Priorities should be on improving busy work and tasks that don’t add value for stakeholders. The benefit of prioritizing these activities for digital technology solutions is that implementation is simpler and critical customer interactions are not affected. The organization can then build momentum toward more complicated tasks and solutions.

Introduction

The power of today’s digital technologies extends to tasks traditionally performed by humans, such as transcribing human speech, detecting and characterizing abnormalities in medical images, predicting complications or patient deterioration, providing real-time decision support, and in some clinical domains even suggesting possible diagnoses. Done right, digital solutions can create substantial efficiency gains, quality improvements, and superior experience for consumers and health care practitioners.

However, the health care industry in general and provider organizations in particular have been slow to adopt digital technologies and much activity to date has been in pilots rather than wide-scale implementation. In our 2020 survey on AI, 17% of health care executives reported that their organizations had no sophistication or a very low level of sophistication with AI compared to only 11% of executives from other industries.3 And in our 2019 study on the future of work, only 27% of health care executives said that they had invested in automation technologies.4 Previous research suggests that health care executives and physicians have serious concerns about digital technologies in general and AI in particular, including privacy, ethical concerns, and the risk of medical errors.5

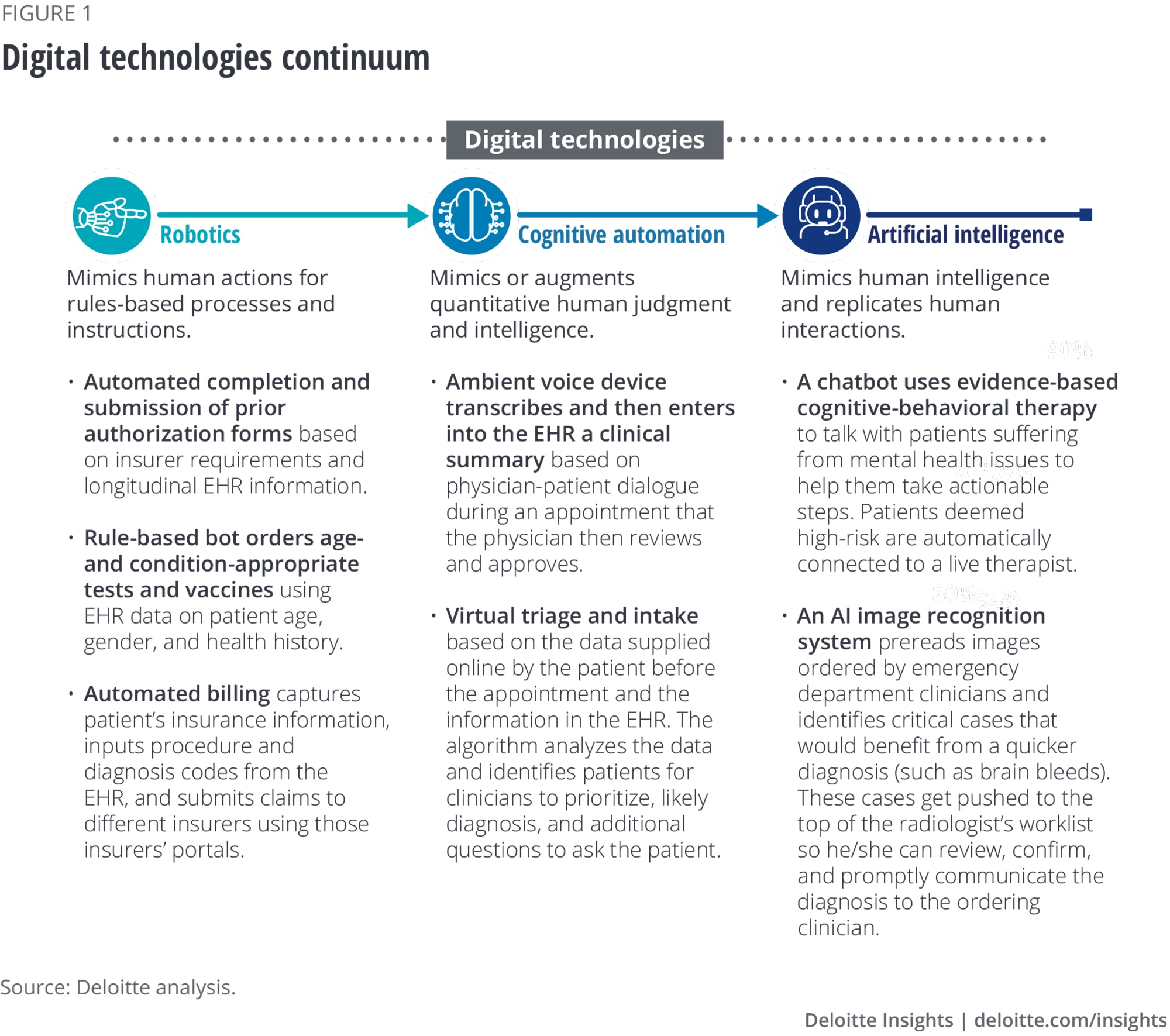

We sought to understand the perspective of physicians as key stakeholders in adopting and using technology. We focused questions on emerging digital technologies, providing use cases for robotic process automation, natural language processing, and machine learning (similar to those described in figure 1 in the “The digital technologies continuum” sidebar). We found that physicians are open to specific examples of new technological solutions.

The digital technologies continuum

Rather than describing what an individual technology can do or how it is defined, in figure 1, we draw parallels to human activities to illustrate the potential of digital technologies to improve physician work. As the continuum suggests, the implementation complexity would typically increase as the tasks we try to perform or streamline with technology move further away from rule-based processes. As a basic feasibility aide, this continuum can help prioritize or sequence investments in digital solutions, particularly for organizations new to digital transformation.

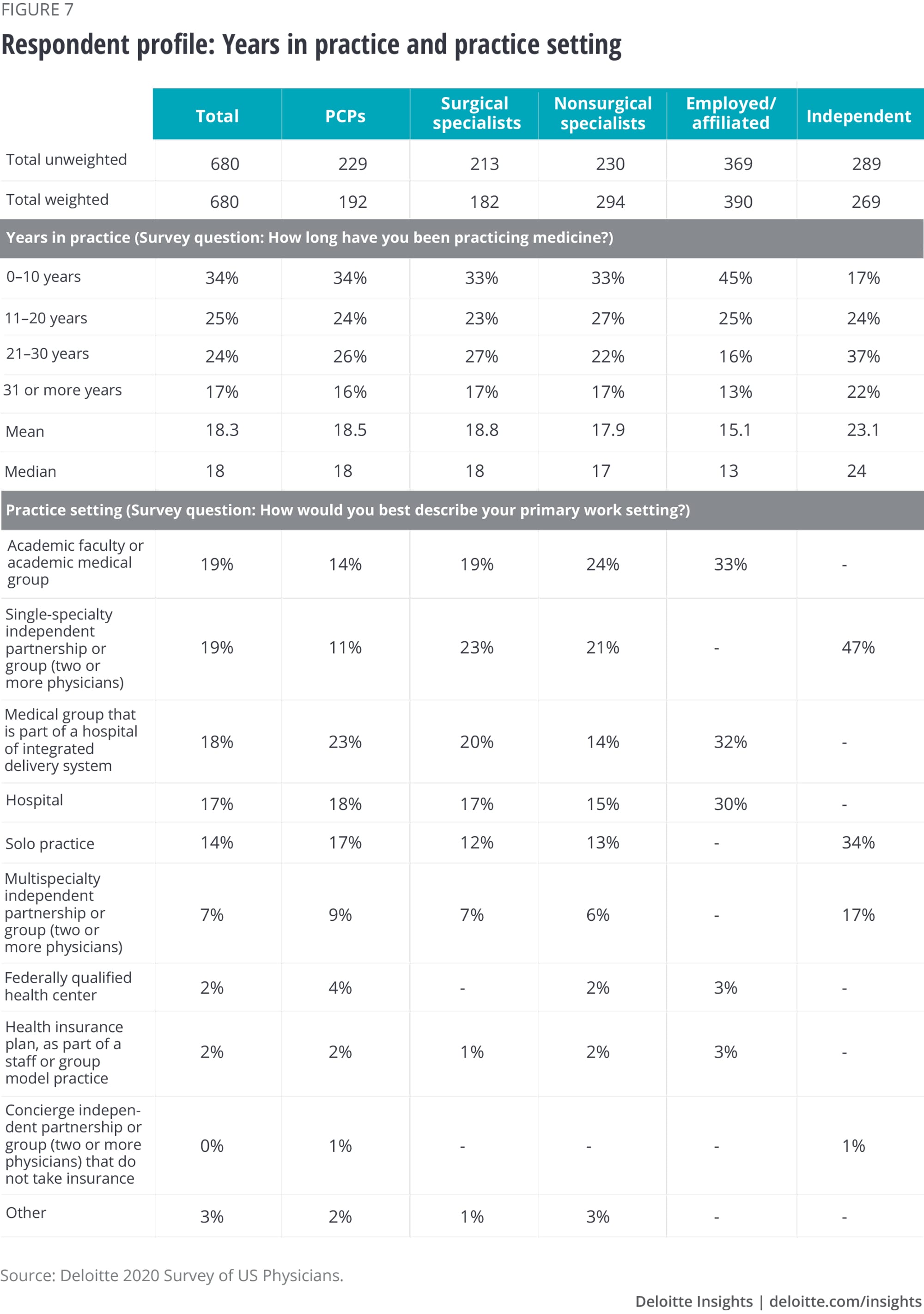

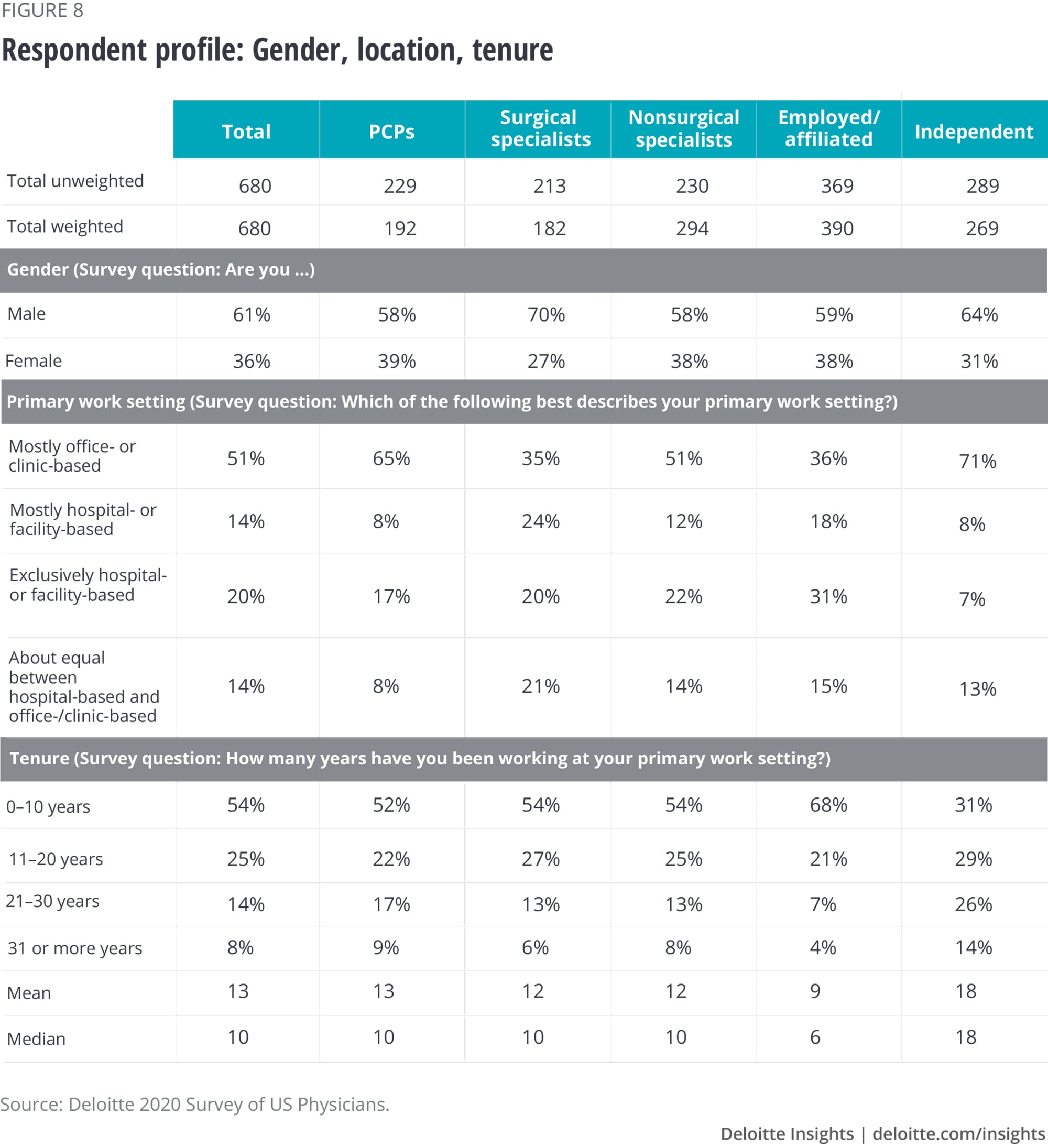

Methodology

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions fielded its biennial survey of US physicians, performed since 2011, from January 15 to February 14, 2020. This survey is nationally representative of US primary care and specialty physicians with respect to years in practice, gender, geography, practice type, and specialty. In 2020, 680 US primary care and specialty physicians were asked about a range of topics: future of work, future of health, virtual health, digital transformation, and value-based care.

In the digital technology portion of the survey, respondents were first asked to rate technology use cases for their practice. This set the context for the subsequent questions about respondents’ support of such solutions, expected impact, and reservations they may have about adopting them.

See the Appendix for detailed information on our sample.

Physicians see benefit to emerging digital technologies but want proof of their effectiveness

Physicians point to efficiency as the greatest potential from emerging digital technologies. Physicians expect efficiency to be the biggest benefit of AI for the industry (figure 2). They note other benefits too, such as improved job satisfaction, accuracy in diagnosis, and patient experience, but those are distant responses compared to “saving time and resources.” The expectation of AI to support diagnostic accuracy expressed by 42% of physicians is of note and may signal growing trust and comfort with AI-based diagnostic solutions, as long as they produce reliable results.

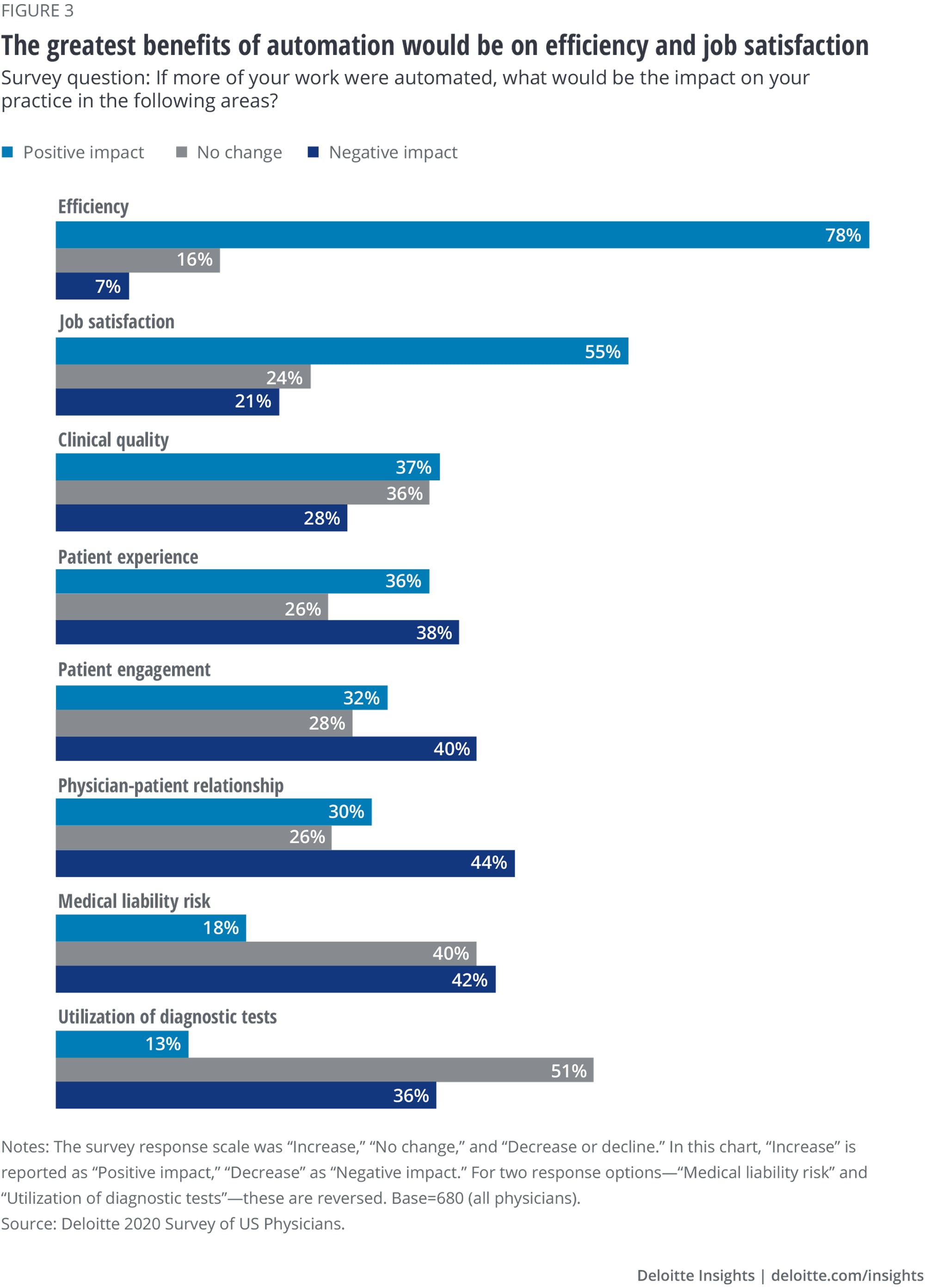

Greater efficiency is also the top benefit physicians expect as a result of automation in their practice. They also note a positive impact of automation on their job satisfaction and clinical quality (figure 3).

Interestingly, primary care physicians (PCPs) are more likely than specialists to expect benefits from automation along multiple dimensions. For instance, among PCPs, 40% expect a positive impact on clinical quality, 42% on patient experience, 39% on patient engagement, and 35% on physician-patient relationship. Nonsurgical specialists are the most skeptical, particularly when it comes to patient engagement and patient experience: Forty-five percent and 42%, respectively, expect a negative impact from automation in these areas.

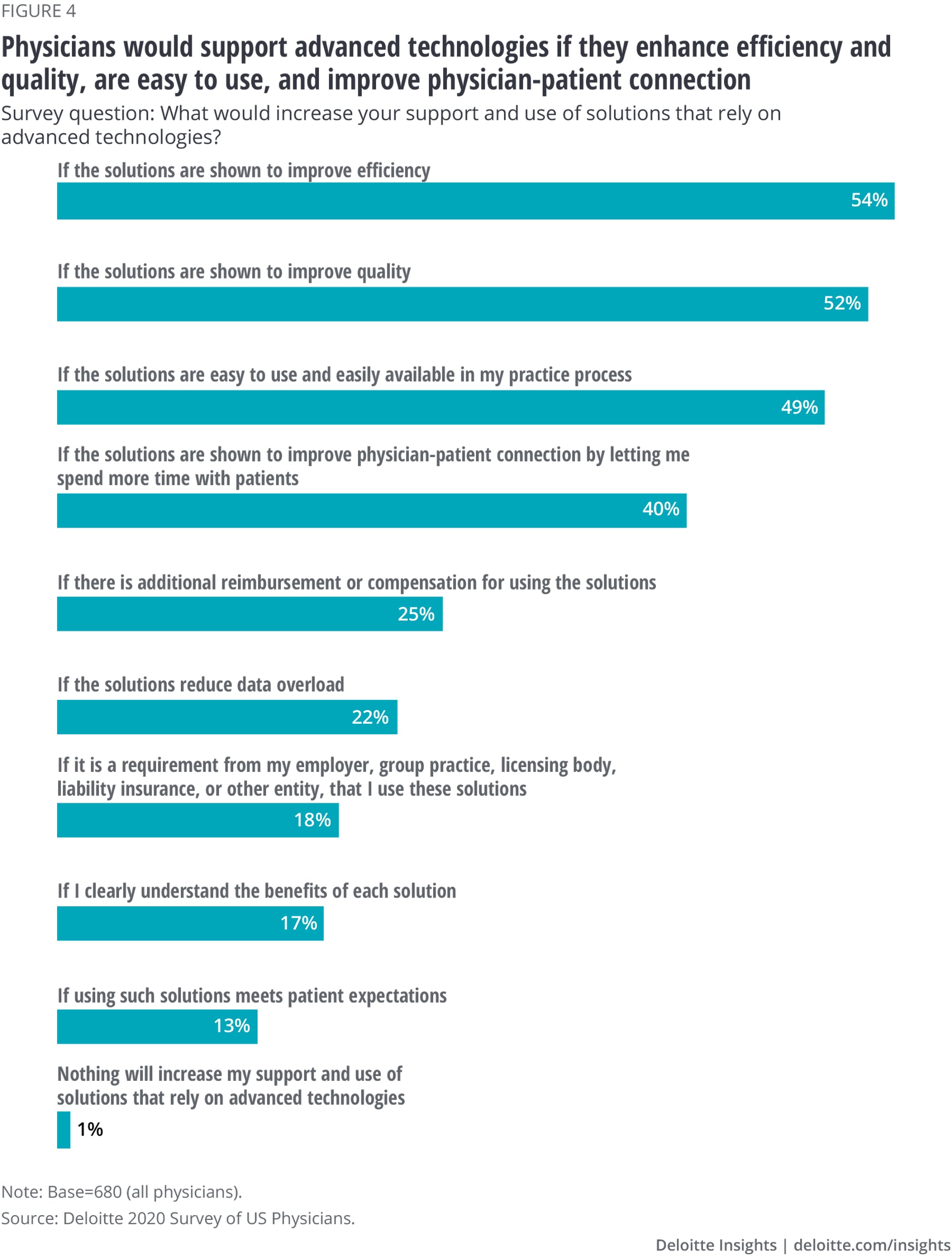

To increase their use and support of AI-driven technologies, physicians call for demonstrated efficiencies, proven improvement of quality, and ease of use (figure 4). When planning and piloting digital solutions, organizations should ensure they develop and communicate these proof points to stakeholders.

As demonstrated in case study 1, improved efficiency, quality, and experience of care for clinicians and patients may all come from technology applications.

Case study 1. Closing gaps in care6

Observations of existing processes at a health system’s primary care clinics showed that clinicians often failed to close care gaps during patient visits when presented with visual indicators in the EHR flagging those gaps (e.g., a need for a colonoscopy or a pneumonia vaccine). It turned out that several action steps were required on the part of the clinician to close the gap. For instance, when a patient was due for a pneumonia vaccine, somebody needed to check whether to order a booster shot or the initial dose, and this activity was typically performed after the visit, resulting in a missed opportunity for patient education and gap closure.

To address these gaps, the organization enabled an automated process that reviews the patient record in advance of the visit, including prior history. It then prepares an order for the right treatment (vaccine vs. booster) or a necessary referral (e.g., colonoscopy or mammogram). As a result, the provider no longer needs to search for the correct action and is prepared to deliver the treatment or provide the referral during the patient visit. The organization improved its performance on closing care gaps by 30-50 percentage points without increasing the burden on its clinicians. Not a single PCP opted out after the pilot phase.

Despite physicians’ interest in technology for administrative purposes and efficiency, availability is low

When asked about opportunities for automation, physicians prioritize automating administrative tasks over patient interactions. But despite listing many use cases for automation, few physicians report they have been implemented at their organizations (figure 5).

Among activities presented in the survey, physicians say coding and completing prior authorization requirements (typically performed by other staff) are most promising for automation. Two in five physicians believe that tasks associated with patient interactions do not lend themselves to automation. One in five reports that data entry for quality reporting is already automated in their organizations, the top response for availability.

Case study 2 demonstrates that routine administrative processes can be candidates to leverage technology, whereas case study 3 shows that large efficiency gains can be achieved through a curated patient history and that automating certain patient interactions can actually improve patient experience.

Case study 2. Streamlining patient scheduling7

One health system implemented a fully automated system that looks at schedules and identifies appointment cancellations. Once a cancellation is found, it contacts patients on a waiting list to offer them earlier appointments to book online. This improves patient experience—giving them an earlier appointment—and reduces no-shows due to late cancellations. It also eliminates the classic phone tag between receptionists and patients.

Case study 3. Improving access to care through asynchronous virtual visits8

In rural areas, many patients travel long distances to receive care. However, for much low-acuity primary care, in-person visits may not even be necessary. One rural hospital implemented a solution that enables patients to receive care remotely.

Patients who sign up to use the solution complete an online questionnaire about their symptoms, medications, health history, and confirm their preferred pharmacy. The solution then curates the information from the online questionnaire and the patient’s health record for a clinician’s review. It takes clinicians only two to three minutes to review this information and issue a diagnosis and treatment plan without ever touching the EHR. The patient gets a response within an hour or sooner, and the completed visit automatically goes into the patient’s record. Adding this service cuts the time clinicians spend on low-acuity visits, enabling them to focus on complex patient care. In a typical month, clinicians conduct between 45 and 60 exams using this service.

Physicians have some concerns about emerging digital technologies

Despite seeing the potential for digital technologies, our survey respondents also raised some concerns: a negative impact on the physician-patient relationship (44%), an increase in medical liability risk (42%), and lower patient engagement (40%) (figure 3). When asked about questions that they may have regarding AI-driven solutions, 69% of physicians ask who is liable when the technology makes a mistake.

These are valid concerns shared by physicians, executives, and technology experts.9 Unless physicians trust the technology, they may choose not to use it even if it’s available. Case study 4 illustrates this point.

Case study 4. Engagement of physicians should not be an afterthought10

One large health maintenance organization (HMO) found that when members search the internet for information on common symptoms, such as headaches and nausea, they often conclude that they have rare and dangerous ailments because the symptoms match. The HMO implemented a symptom checking app to give members information about the actions of similar people (with the same age, gender, and symptoms as the user): what proportion visited a PCP, a specialist, a pharmacy, or self-treated, what kind of medication they took, and what diagnostic tests they had. If the user has more questions, they can engage in a direct chat with a doctor who can make a quick decision about the next steps using the symptoms summary from the chat history.

When the app was first introduced, physicians were mistrustful and intimidated by the new technology and the change it might bring about. It slowed down the rollout of the technology. With earlier engagement and communication with physicians, these delays could have been avoided. Now, physicians enjoy the app: They appreciate the efficiency of the diagnostic process and quality of the information for members, particularly Generation Z who typically do not have a regular doctor.

Physicians offer insight on where to start with digital technology investments

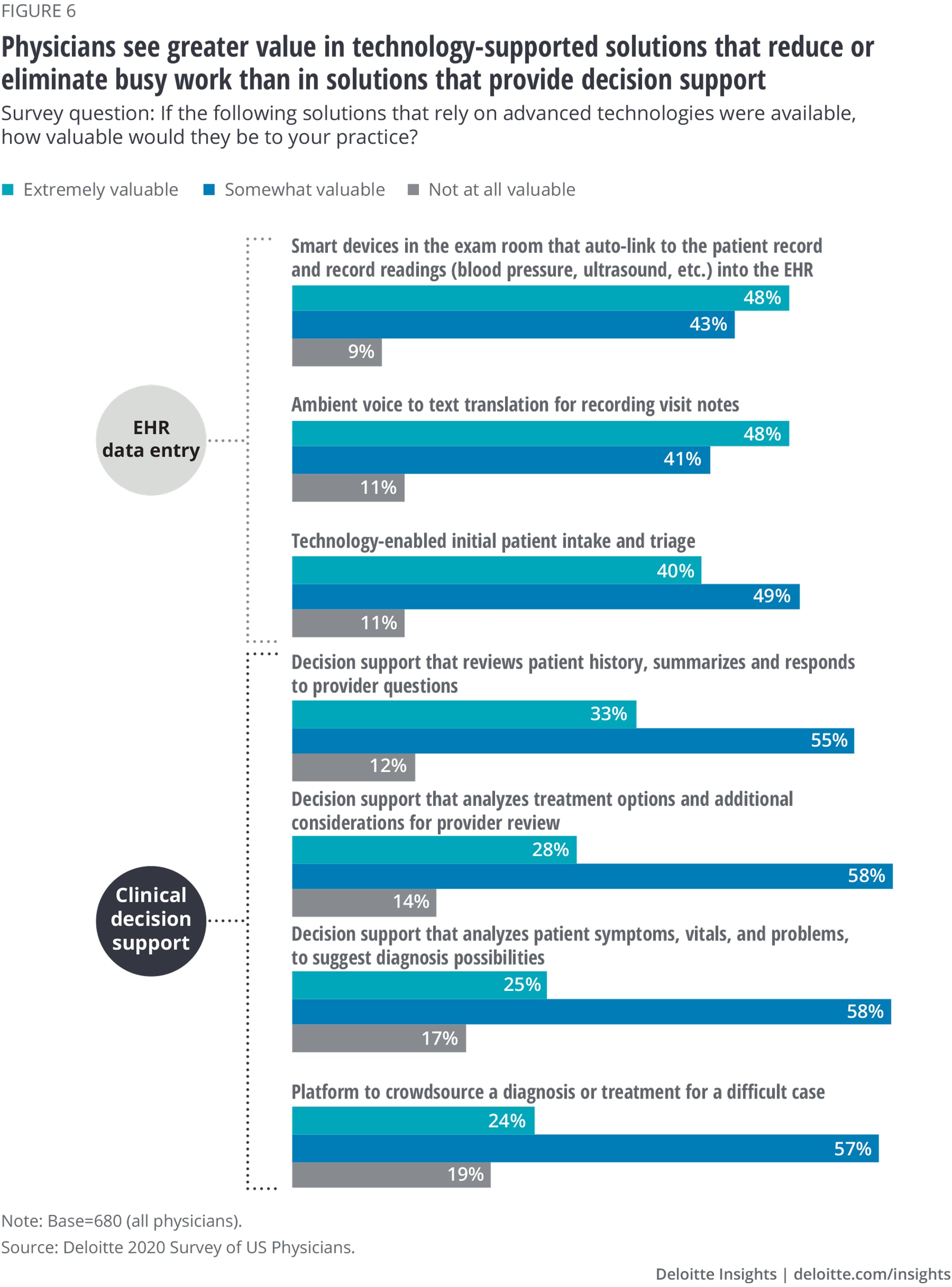

Physicians’ reactions to use cases in our survey offer insight on where executives should launch their efforts. When asked to consider the value of use cases that involve EHR-related tasks vs. use cases for clinical decision support, physicians see greater value in those that streamline EHR-related tasks. These use cases include digital technologies for recording vitals, taking notes, triaging, and intake forms (figure 6).

Conclusion: Embracing digital

Physicians agree with many executives on the goals for adoption of new technologies,11 so health care organizations should focus on execution and demonstrating impact. Many vendors offer digital technology solutions and it is easy to get distracted by shiny objects. It can be helpful to think of a technology project as a process improvement that supports specific strategic goals. This can help executives resist opportunities that create disjointed and misaligned technology plug-ins. To help ensure initiatives and investments are aligned, executives should consider a broader organizational approach:

- Define an organizational strategy and vision for digital technology

- Evaluate solutions to ensure that they align with specific performance goals and define clear criteria for priorities and pilots

- Develop competencies to build the technologies in-house and determine where external support or outsourcing is needed

- Engage key stakeholders, both at the top for executive buy-in and on the ground to understand user perspective and impact on stakeholders

To launch efforts, executives should consider projects that are low-hanging fruit, including those that have a proven ROI and are a known pain point for stakeholders—consumers, physicians, and staff. Furthermore, when organizations identify and prioritize opportunities, they should not dismiss the more mundane processes (such as revenue cycle, scheduling, and workflow), as these areas may call for simpler technological solutions and still generate large ROI due to high volume of the activities that can be streamlined or simplified. Another benefit of prioritizing these is that critical customer interactions are not affected should mistakes happen.

Use cases that surveyed physicians say have the most value for their practice or where they recognize the greatest potential could be a starting point for identifying and prioritizing opportunities:

- Automating prior authorization requests and clinical coding for billing

- Smart devices in the exam room that auto-link vitals to the EHR

- Ambient voice devices that translate and record documentation notes

- Technology-enabled intake and triage

Another thing to consider is that physicians and other stakeholders may not have uniform views or preexisting experiences with technologies, thus identifying user segments most open to new solutions can help with adoption. Our survey suggests PCPs are more likely to see value in digital solutions; and while this might be the case on average, we recommend organizations develop a closer understanding of their own user base as part of the stakeholder engagement process.

Health care organizations have the opportunity to finally realize the promise of technology. In the end, involving key physicians and physician leaders in the process, communicating the benefits and proof points, prioritizing efficiencies, and minimizing disruption to physician workflow could alleviate concerns physicians may have about new digital tools.

Appendix—Methodology

Since 2011, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions has surveyed a nationally representative sample of US physicians on their attitudes and perceptions about the current market trends impacting medicine and future state of the practice of medicine.

The general aim of the survey is to understand physician adoption and perception of key market trends of interest to the health care, life sciences, and government sectors.

In 2020, 680 US primary care and specialty physicians were asked about a range of topics: future of work, future of health, virtual health, digital transformation, and value-based care. In the digital technology portion of the survey, respondents were first asked to rate technology use cases for their practice. This set the context for the subsequent questions about respondents’ support of such solutions, expected impact, and reservations they may have about adopting them.

The national sample is representative of the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile with respect to years in practice, gender, geography, practice type, and specialty to reflect the national distribution of US physicians. Data collection took place between January 15 and February 14, 2020.

About the AMA

The AMA is the major association for US physicians and its Masterfile is a census of all US physicians (not just AMA members). The database contains records of more than 1.4 million US physicians and is based upon graduating medical school and specialty certification records. It is used for both state and federal credentialing, as well as for licensure purposes. This database is widely regarded as the gold standard for health policy work among PCPs and specialists, and is the source used by the federal government and academic researchers for survey studies among physicians. We selected a random sample of physician records with complete mailing information from the AMA Masterfile, and stratified it by physician specialty, to invite participation in an online 20-minute survey.

More on digital health

-

The future of medtech Video4 years ago

-

The future of virtual health Article4 years ago

-

Digital health technology Article5 years ago

-

Six assumptions for measuring health disruption Interactive4 years ago

-

How the virtual health landscape is shifting in a rapidly changing world Article4 years ago