Disarming the Value Killers has been saved

Disarming the Value Killers A risk management study

02 April 2005

- Vikram Mahidhar

Steep market falls are not uncommon, and the effects often last long. A look into the fall in share prices from 1994–2003 brings to light some common risk factors and lessons to be learned.

Executive summary

Investors and executives share a mutual desire for the success of their company, but they also harbor a common fear: a precipitous drop in share price that results in restricted credit, impeded growth, decimated pension plans, and reduced competitiveness. Unfortunately, unlike many concerns, this phobia is grounded in reality. Steep market drops affect a significant percentage of companies, encumbering them with negative repercussions that can last for years.

Indeed, over the last decade, almost half of the 1,000 largest global companies suffered share price declines of more than 20 percent in a one-month period, relative to the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) World Index. By the end of 2003, roughly a quarter of these companies had still not recovered their lost market value. Another quarter took more than a year for their share prices to recover.

Steep market drops affect a significant percentage of companies, encumbering them with negative repercussions that can last for years.

Although each of these companies experienced unique circumstances that contributed to their loss of value, there are several common underlying risk factors that resulted in a negative effect on value. Deloitte Research, a part of Deloitte Services LP, analyzed the factors underlying these major losses in value from 1994 to 2003, with the goal of identifying strategies that companies might follow to manage risk and better protect shareholder value.

Key findings

Manage critical risk interdependencies

- Critical concern: Eighty percent of the companies that suffered the greatest losses in value were exposed to more than one type of risk. But firms may fail to recognize and manage the relationships among different types of risks. Actions taken to address one type of risk, such as strategic risk, can often increase exposure to other risks, such as operational or financial risks.

- Recommended response: Companies need to implement an integrated risk management function to identify and manage interdependencies among all the risks the firm faces.

Foster a strong ethics and control culture

- Critical concern: Corporate cultures and incentive systems that set a high premium on returns without complementary controls can lead to major value and brand losses.

- Recommended response: Senior management needs to create a culture emphasizing the importance of ethical behavior, quality control, and risk management. Compensation incentives should be aligned with long-term value creation and brand protection.

Proactively address low-frequency, high-impact risks

- Critical concern: Some of the greatest value losses were caused by exceptional events such as the Asian financial crisis, the bursting of the technology bubble, and the September 11 terrorist attacks. Yet many firms apparently fail to plan for these rare but high-impact risks.

- Recommended response: Firms should employ “stress testing” to ensure that their internal controls and business continuity plans can withstand the shock of a high-impact event. Companies should proactively plan and acquire the strategic flexibility to respond to specific scenarios.

Provide timely information on control factors

- Critical concern: A number of organizations lacked access to the current information required for senior management to respond quickly to emerging problems.

- Recommended response: Firms need to improve their internal information systems, and communication mechanisms to ensure that senior management and boards of directors receive accurate, near real-time information on the causes, financial impact, and possible solutions of control problems.

Given the frequency of sudden and dramatic drops in share prices, even the largest companies need to take a serious look at current risk management practices. Companies that go beyond traditional methods to take a more integrated and comprehensive approach to risk management may reduce the likelihood of suffering major losses in value.

It’s dangerous out there

Consider a senior executive’s worst nightmare: In just a few days, the company’s share price plummets. Available credit quickly dries up. Expansion plans are put on hold. The firm takes years to recover its original value, and by the time it does so, senior management has been replaced.

Unfortunately, this nightmare is all too often a reality for some of the world’s largest companies.

What causes major losses of shareholder value? And what steps can senior management take to minimize the risks? To answer these questions, Deloitte Research analyzed major losses in shareholder value over the last decade. While the past does not necessarily predict the future, understanding the factors that have destroyed corporate value suggests ways in which firms can reduce their vulnerability to these sudden shocks.

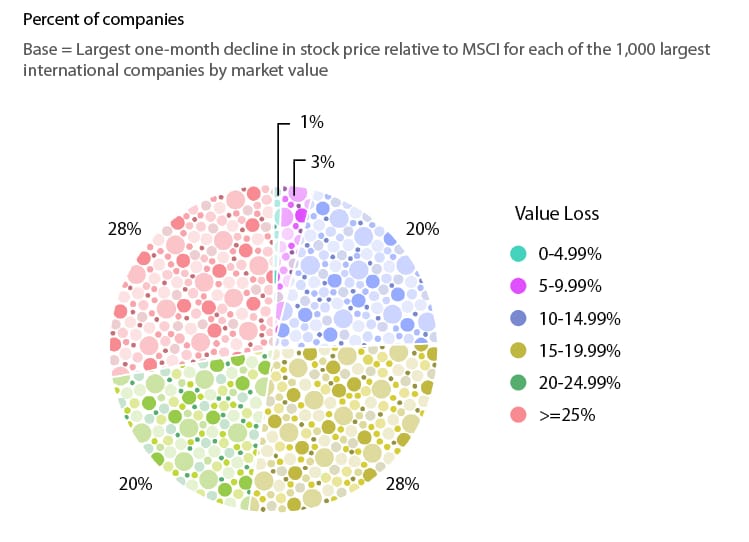

The analysis identified the largest one-month declines in share price among the 1,000 largest international companies (based on market value) from 1994 and 2003. The results were sobering: almost half of the companies had lost more than 20 percent of their market value over a one-month period at least once in the last decade relative to the MSCI world stock index (see exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1. Declines in share price among the largest international companies (1994-2003)

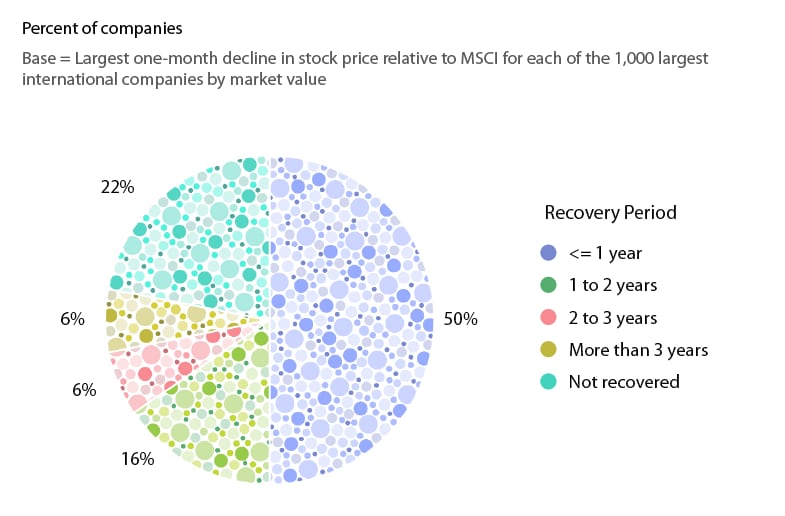

And the value losses were often long-lasting. Roughly a quarter of the companies took longer than a year before their share prices recovered to their original levels, sometimes much longer. By the end of 2003, the share prices of almost a quarter of the companies had still not recovered to their original levels (see exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2. Time required for share price to recover (1994-2003)

What caused these dramatic and enduring losses in market value? To understand the origins, the 100 companies that suffered the greatest declines in share price from 1994 to 2003 were examined. Public disclosures, analyst reports, and news articles on each firm provided insights into the underlying events that accounted for their lost value.

Adapting the COSO framework,1 events were divided into four broad risk categories:

- Strategic risks, such as demand shortfalls, failures to address competitor moves, or problems in executing mergers

- Operational risks, such as cost overruns, accounting problems from failures in internal controls, and supply chain failures

- Financial risks, such as high debt, inadequate reserves to manage increases in interest rates, poor financial management, and trading losses

- External risks, such as an industry crises, country-specific political or economic issues, terrorist acts, and public health crises

A detailed breakdown of the frequency of the risk events that fell into each of these categories is provided in exhibit 3.

Clearly, companies are confronted by a wide variety of potential value killers. To make the challenge even more complex, many declines in share price were the result of cascading losses from two or more types of risk events working in combination. More than 80 percent of the 100 companies that suffered the greatest losses experienced risk events of more than one type. Low-probability but high-impact events also played an important role.

Many companies already have some form of an enterprise risk management system, but still experience losses. Can these substantial value losses be prevented? Not always, but senior management and the board of directors can take steps to reduce their firm’s risk exposure and improve corporate resilience.

Four key steps can help companies guard against potentially devastating losses in value:

- Manage critical risk interdependencies

- Address low-frequency, high-impact risks

- Foster a strong, ethical control culture

- Provide timely information

These strategies are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Exhibit 3. Possible causes of value loss

Note: The numbers do not total to 100, since companies experienced more than one type of risk. See Appendix 2 for a more detailed analysis of risks contributing to the 100 largest value drops.

Manage critical risk interdependencies

Multiple risks can escalate losses

Case study

Following its fourth profit warning in five quarters, the shares of a major manufacturer plunged by more than 25 percent. The firm lost more than half its market value over the course of the year. Traditionally a market leader, the firm appeared to be slow to respond to the strategic risk posed by competitors aggressively introducing products with new features. But its effort to reduce costs through a massive reorganization left it vulnerable to operational risk as well. The firm consolidated more than 30 administrative centers into just three, which apparently slowed order fulfillment and billing, and increased customer administration costs and accounts receivable.

Case study

After announcing that operating profits for the year would be 20 percent below expectations, a high-technology equipment manufacturer quickly lost more than 40 percent of its market value. One probable cause was the external risk resulting from the privatization of several telephone operators in Europe, which led to a drastic reduction in its orders. The company did not appear to incorporate its customers’ vulnerability to deregulation into its own risk strategy. The impact was perhaps more pronounced since the firm faced greater strategic risk by not having diversified its customer base from incumbent telephone operators to new competitors.

Many value losses are caused by several types of risk interacting to produce an even greater loss in value. Along with assessing internal risk dependencies, firms need to understand the risk profiles of their key suppliers and customers to assess the potential impact of those vulnerabilities on their overall risk profile. In addition, firms take actions to address one type of risk that unwittingly increase their exposure to other risk categories. Risk management strategies should include an analysis of how responses to one type of risk might trigger other types of risks.

While many firms have invested in enterprise risk management, few adequately manage risk interdependencies. Most firms manage risk in “silos,” often leaving them blind to relationships between risks. For example, in a 2003 survey of financial services executives by the Global Association of Risk Professionals, more than half said their firm used disparate systems for operational risk and credit risk, while only 10 percent said they had integrated technology that covers both sets of risks.2 Modeling and managing these interdependencies is essential to the prevention of one type of risk management failure cascading into other types of risk events.

How can managers gain a comprehensive view of risk interdependencies? The essential first step is to build an integrated risk management function, championed and supported by senior management, that is positioned above all divisions and departments. The purpose of this group is to identify the key risks across the corporation, understand the connections between them, and develop a risk-management strategy that takes into consideration the organization’s appetite for risk.3

While many firms have invested in enterprise risk management, few adequately manage risk interdependencies. Most firms manage risk in “silos,” often leaving them blind to relationships between risks.

For example, Bank of America integrates risk management at the time business strategies are developed, rather than planning for risk after a strategy has been established. Central to their approach is looking at risks holistically, rather than in isolation. For instance, when considering risks in the underwriting process, the bank assesses how its business strategy, sales practices, and business development practices affect the risk profile of what is underwritten.4

This comprehensive approach not only helps the organization reduce overall risk but can also lower the costs of risk management. For example, Honeywell formerly bought product liability, property, and foreign exchange insurance policies separately. By understanding the risk interdependencies of these products, it developed a comprehensive insurance contract with American International Group that bundled several different kinds of policies. This has enabled the company to cut its overall risk abatement costs by more than 15 percent.5

Address low-frequency, high-impact risks

What are the odds?

Case study

A manufacturer with a long history of product innovation enjoyed steady growth until the telecommunications bubble burst in 2000. The firm had built up debt, as it invested billions in new telecommunications technologies and company acquisitions. But no financial safety net had been created for what appeared to be the extremely unlikely possibility of an industry-wide demand crisis. When a demand crisis did occur, the firm’s share price plummeted by almost 50 percent in just two days.

Case study

In the early 1990s, a Mexican manufacturer used dollar debt from major U.S. banks to acquire plants in other Latin American countries and modernize operations. By the end of 1994, about three-quarters of the company’s debt was in dollars, while the company’s revenues were largely peso-denominated. The company had not prepared for the unlikely event of a major currency devaluation coupled with an economic crisis. During the Mexican financial crisis of 1995, the devaluation of the peso and the resulting recession slashed cash flow from its Mexican operations by more than 50 percent in dollar terms. The company survived by arranging emergency financing.

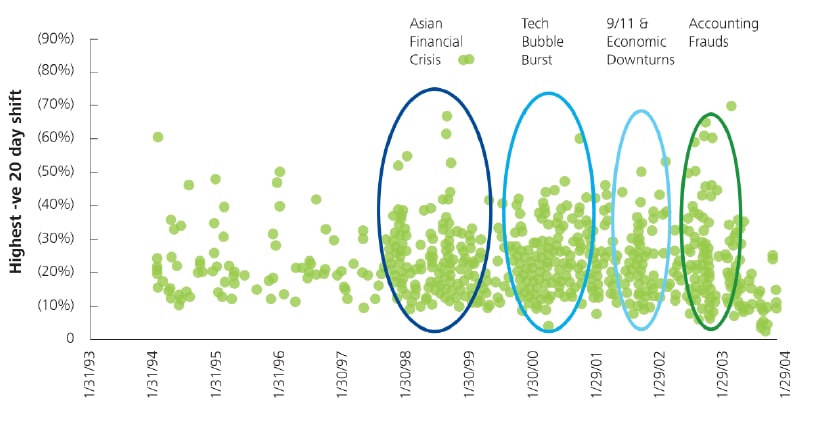

Many of the largest value losses were the result of events that were considered extremely unlikely. Rare events that can dramatically destroy value include terrorist acts, industry crises, country crises, currency crises, and natural disasters (see exhibit 4).

Despite the potentially devastating impact of unlikely events, managers often emphasize the most likely risks faced by a company when assessing its risk position. Probabilistic models like Value-at-Risk (VaR) are developed using likelihood and impact data for similar events. These models may be biased to focus on the more frequent risks, overlooking low-probability events that can be extremely damaging. For instance, the Asian financial crisis and the September 11 terrorist attacks were two unprecedented events with a major business impact that caught many firms unprepared. Such events cannot easily be classified into a probabilistic model, and usually data are not available to model these risks.

While rare events are not always preventable, companies can improve the resilience of their operational and capital structures to better manage them. Stress tests and scenario analyses can be used to understand the potential negative impacts from rare events that are typically omitted in risk models. A stress test examines a company’s ability to withstand specific scenarios and events, without having to develop a statistical model of them. They are a crucial addition to VaR models in allowing executives to answer the question: “What can go terribly wrong?”

Exhibit 4. Rare events can devastate value

Impact of recent low-probability events on value losses

Scenarios for stress tests can be historical, in which a company simulates the market moves observed in a past crisis. For example, a company could ask how it might respond to an earnings shortfall resulting from a repetition of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Historical scenarios are attractive because all relationships between markets are specified at once. On the other hand, past market moves will never recur precisely. For this reason, many firms specify hypothetical scenarios, with events that have never previously occurred—such as responding to oil supply interruptions, leading to prices in excess of $60 a barrel. Banks and brokerage firms often stress-test their portfolios and likely responses to various scenarios.

While rare events are not always preventable, companies can improve the resilience of their operational and capital structures to better manage them.

In addition to stress-testing responses to low-frequency events, firms should acquire greater capabilities to plan for and respond to specific scenarios. A firm can build the flexibility to respond to different scenarios by selectively investing in capabilities that can be exercised in the event of a specific scenario being realized. For example, a firm might take a partial equity stake in a company in another market or region with the option to migrate to full ownership, or a media company could simultaneously support many different technologies and strategies for online media distribution until standards become well-defined. By initially supporting multiple technologies, the vendor in effect takes a “real option” to allow it to adapt quickly to future market conditions.

Deloitte Research has developed a “strategic flexibility” methodology that allows firms to become more nimble in managing strategic risks. The methodology combines scenario planning with real options to possibly help companies better navigate an uncertain and shifting business environment. The methodology is described in a series of reports on Strategic Flexibility published by Deloitte Research.6

In addition, the concept of business continuity planning has gained currency following the September 11 terrorist attacks, the proliferation of computer network viruses, the rash of severe weather events, and other risks. The ability to continue functioning after a major disruption is essential for companies that can afford little or no downtime in their business operations. Yet recent research shows business continuity programs are often not addressed at the enterprise level, and that companies frequently do not take into account dependencies on third parties such as vendors and suppliers.7

Foster a strong culture supporting ethical conduct

They reaped what they sowed

Case study

A major manufacturer was forced to recall millions of its products due to safety defects. With powerful financial incentives in place to meet production targets, workers had used questionable tactics to speed up production and managers had given short shrift to inspections. The widespread quality problems forced the firm to post losses of hundreds of millions of dollars in two quarters, while driving net profits down almost 50 percent. The cost of the recall and expectations that sales would tumble knocked 45 percent off the firm’s stock price within a month.

Case study

In just two days, a major healthcare firm saw its share price plunge by almost half and $6 billion in market value evaporate. The company had looked like a high flyer, but its extraordinary growth had come at the expense of an ethical corporate culture and solid controls. A variety of lawsuits filed against it had alleged fraudulent billing and other improprieties in government health programs, under-staffing, and labor violations. When it was reported that changes in Medicare payment procedures would cut the company’s revenues and that the federal government was investigating allegations of unnecessary surgery, its stock price nosedived.

Unless a company has built an ethical corporate culture and effective controls, aggressive strategies to generate profits or slash costs can motivate employees to engage in fraudulent and inappropriate business activities. These practices increase a firm’s exposure to operational and financial risks, which can severely damage its reputation and brand.

A permissive corporate culture or a lax control system contributed to many high-profile value losses in the past decade. A 2003 study of major corporate governance failures and frauds found that the most common transgressions were related to the overstating of net profits.8 Firms used a variety of fraudulent accounting strategies affecting revenues, expenses, and special reserve accounts. In the worst cases, a significant number of senior company executives openly tapped company funds for their personal benefit, profited from insider trading, or misled the public in their corporate disclosures.

Several structural changes have been legislated or adopted to improve control systems and processes, such as Sarbanes-Oxley in the United States, which calls for increased disclosures by public companies and improvement in their control environments, or the Turnbull report in the United Kingdom. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and stock exchanges such as the New York Exchange have also promulgated new governance and listing requirements. The increased attention to risk management from investors and the media has led many firms to upgrade their risk management and monitoring systems against fraud and unethical business practices.

These legislatives and structural initiatives will only be effective, however, if a firm has created a sound ethical culture. A corporate culture frames the shared beliefs of most members of an organization in terms of how they are expected to think, feel, and act as they conduct business each day. A firm’s culture can often guide employee behavior more consistently than formal rules. Setting or changing a firm’s culture is a key leadership activity that must start at the top. It requires senior management to consistently communicate—through actions even more than words—the ethics and key values of the firm. These values should include honestly dealing with difficult situations by directly addressing bad news rather than avoiding it, sharing information, keeping commitments, and not emphasizing the ends over the means.

One step to identifying potential cultural pitfalls is to appraise the current ethics and cultural environment. This can be done through a confidential survey administered both to management and rank-and-file employees. The survey provides an opportunity to compare opinions across different levels of the organization.9

With the Sarbanes-Oxley Act requiring company management to file quarterly and annual reports on internal control over financial reporting and disclosure, management must take a number of steps to reduce vulnerability to fraud. Beyond fostering a culture of ethical behavior, firms need to implement ethics programs that include written standards for conduct, ethics training, advice lines, and the ability to report fraud anonymously. In addition, fraud detection programs that model different types of possible frauds and monitor the workplace to identify problems are essential to a comprehensive program. These steps can serve to increase the reporting of fraud and help to better manage risks before their costs spiral out of control.10

Provide timely information

In the dark

Case study

After a business service company disclosed that its second quarter earnings would fall short of expectations, investors drove down its share price 37 percent and erased more than $12 billion of its market value. Contributing to the losses was the firm’s inability to offer much explanation as to what had gone wrong. After the turmoil, the firm’s CEO, CFO, and COO, all left the firm.

Case study

A major U.S.-based energy company slashed its profit outlook due to low power prices and fierce competition, sending its stock tumbling by more than 25 percent. The company’s CEO admitted that the firm didn’t have a clear picture of the business situation. Due to deficiencies in its planning and budgeting systems, the company lacked the data that could have given an early warning about the pending situation.

Failures in risk management were often compounded by the lack of timely information for senior executives and boards of directors on the causes, financial impact, and possible resolution of the problem. This naturally reflects poorly on senior executives and their control of the organization, often leading to their departure. The shock felt by investors who suddenly learn about the existence or severity of problems that had previously been undisclosed has often driven share values down even further.

With CEOs and CFOs of U.S. public companies having to attest to the accuracy of financial information to comply with Sarbanes-Oxley requirements, some companies have improved the ability of their information systems to provide more current visibility into their operations. However, this increased knowledge does not necessarily translate into useful information for the board of directors. Board members are inundated with ever larger amounts and kinds of information provided by management just before meetings. As boards of directors confront more complex governance tasks in a more uncertain and demanding environment, firms will have to redesign the way they gather, analyze, and present information to allow board members to discharge their responsibilities. Boards are likely to increasingly demand investments in information systems and staff so they can independently monitor and assess management initiatives, performance, and company operations.

Conclusion

Many of the world’s largest companies suffered tremendous losses in market value over the last decade. Many of these losses occurred due to failures in correctly anticipating, hedging against, and managing diverse risks. Today, risk management is a critical CEO and board issue as regulatory authorities and exchanges promulgate new disclosure and listing requirements that require more explicit information on risks and the risk management practices of the firm. To preserve value, companies need to go beyond risk management in silos to create an integrated, organization-wide risk management function. Firms adopting such a comprehensive approach to risk management will define an overall risk appetite and model critical interdependencies among different types of risks. They will employ stress tests and invest in new capabilities to increase the organization’s ability to withstand low-probability, high-impact risks. While initiatives such as Sarbanes-Oxley are leading to improvements in control and information systems, firms must move beyond simple compliance to invest in creating a culture that motivates employees to act as stewards of corporate value. Finally, business processes and information systems are needed that will apprise senior management and the board of directors in near real time of key risks, anticipated problems, and the firm’s response. While risk can never be eliminated, companies that move beyond traditional risk management to implement a more comprehensive approach to their control environment will be better placed to prevent, minimize, or recover from losses in shareholder value.

To preserve value, companies need to go beyond risk management in silos to create an integrated, organization-wide risk management function.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.