Are you overlooking your greatest source of talent?

31 July 2018

Few large companies have cultures of internal mobility that can help meet skill shortages, prepare the next generation of leaders, and fuel a virtuous talent cycle.

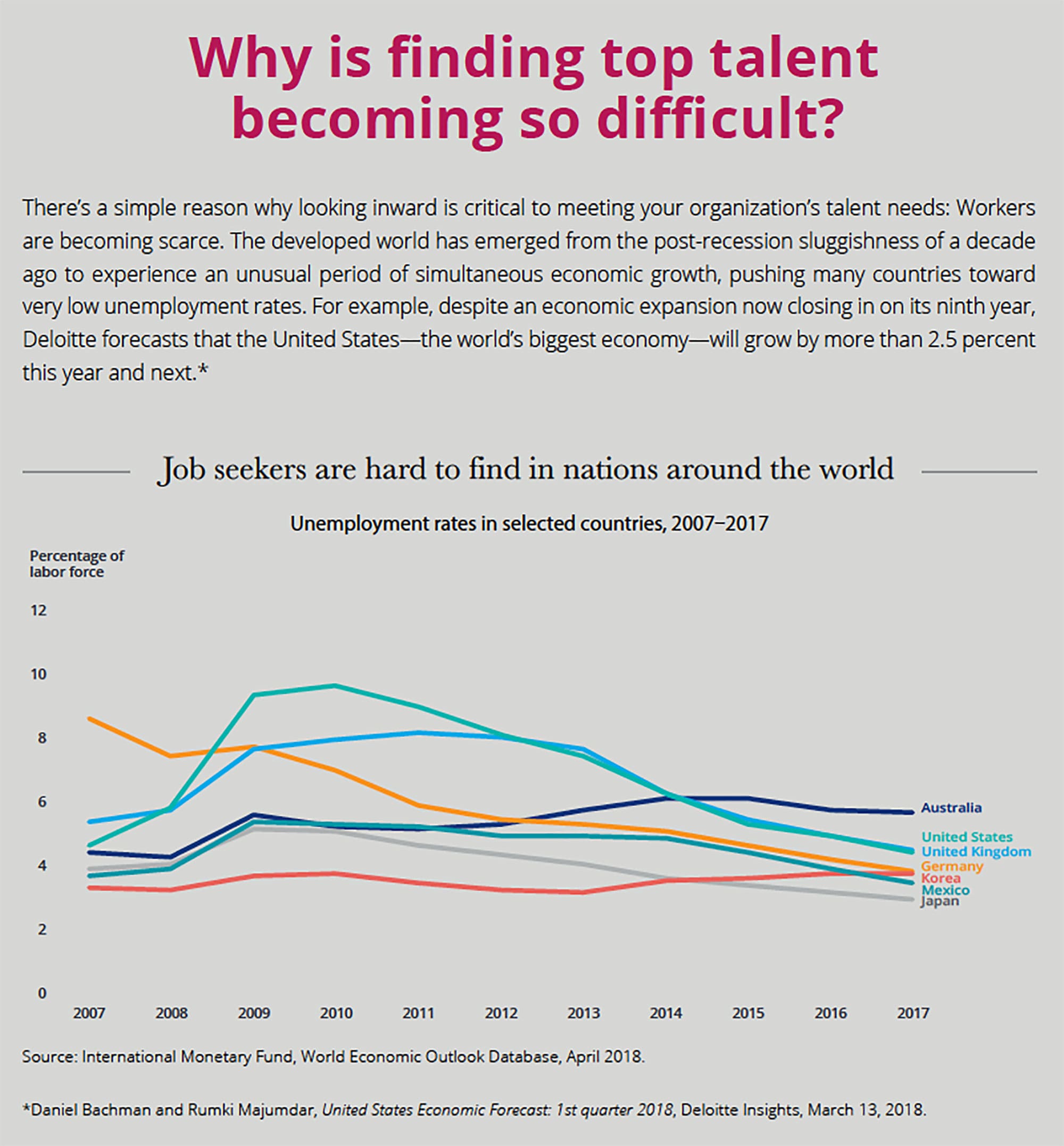

Leaders know that if you want strategic execution, you need the right people and teams. Without them, everything is in doubt. Yet finding the right people is an evergreen struggle—and harder still when unemployment in many countries is at record lows and the job market is booming for the most sought-after individuals. No wonder the task of recruiting, promoting, and retaining talent consumes so many C-suite conversations.1

Learn more

Listen to the related podcast

Explore the Future of Work collection

Subscribe to receive content related to the Future of Work

This article is featured in Deloitte Review, issue 23

Create a custom PDF or download the issue

Which raises the question: Why do so many organizations overlook their greatest source of talent—themselves? Large companies employ tens of thousands of people across geographies, industries, and functions. Yet it’s not unusual for recruiters to be completely unaware that the best candidate for a position may already work inside the organization. In fact, the culture at many companies actively discourages managers from “poaching” workers from other functions. Overcoming these hurdles effectively requires specific tactics and HR-based systems. But, more than that, it requires leaders to build and support a culture where people at all levels are encouraged to—and even expected to—look internally for personal growth and new challenges.

The business opportunity is clear-cut. First, you can avoid replacement and recruitment costs incurred when people leave. But even greater is the opportunity to reshape your employment brand and workplace culture. Many of today’s youngest workers are eager to build their careers rapidly and want to work for organizations that challenge them and promote them quickly. Internal mobility—how that happens—is not just a way to retain talent. It also helps to create a powerful magnet for people outside your organization who seek professional growth. The result? The talent market can see your organization as one that champions ambition and performance in everything it does. Think about what kind of talent you’ll attract and keep—whether inside or outside your organization.

Ways organizations get mobility wrong—and why it matters

For all the talk of robotics, artificial intelligence, and other advanced technologies, people are still needed to run organizations. And it’s getting harder to find them, despite the prevalence of social networks including Glassdoor, LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and others. A strong global economy, healthy job market, and rising employee expectations mean there’s intense competition for talent—and the price for winning keeps going up (see “Why is finding top talent so difficult?” on page 51). Roughly one-half of all workers may be thinking about leaving their jobs,2 and easily can if they have the right capabilities and skills (see figure 1).3

But here’s the thing: What’s driving workers to leave organizations isn’t always just the promise of more money (though that inevitably plays a role). It’s also the opportunity to grow skills and build a career path. Surveys show that all workers—and especially millennials—expect the opportunity to rise within an organization.4 Without that, they’ll likely look elsewhere. And the reality is that workers will always want more than a job. Most want a career path, and the best ones can either find it from you or someone else.

Why it’s so hard to hire internally

This isn’t to suggest that many organizations don’t recognize the value of hiring from within. But knowing something and acting on it are two different things. Organizations often have in place structural hurdles to promoting and recruiting from within—or a culture that discourages it. For example, we’ve seen companies where recruiters go looking for the right people for an opening and find them through social media postings, only to discover they already work there in a different role. And while it’s hard to believe, there are organizations where recruiters are told they cannot reach out to the employees within the company about a different role.

This could require a simple mechanical fix—better internal job posting systems, for example. What’s often tougher to solve is when talent acquisition as a function isn’t included in the internal mobility conversation along with the career management and the learning and development functions or when an organization doesn’t do what’s necessary to prepare people for promotion. Creating a strong culture of internal mobility isn’t just about posting positions on an internal job site. It involves all leaders encouraging and supporting employees to develop the skills that prepare them for their next role, and creating a matching career plan. All too often, such efforts are largely absent: While a 2015 survey found 87 percent of employers agreed a strong internal mobility program would help their retention goals and attract better candidates, only 33 percent of respondents actually had such a program.5

Of course, even when these structures and programs are in place, many managers are loath to lose their stars. Yet the reality is that a culture of talent hoarding can lead to a culture of talent loss: When you block people from moving up within an organization, they often simply go elsewhere. This problem persists at all levels, and the risk of losing high-potential workers is acute with today’s youngest workers. In 2016, according to Deloitte’s millennial survey, slightly less than one-third of millennials believed their organization was making the most of their skills and experience6—a stunning failure to leverage talent given the relationship between workers, strategic execution, and financial performance. And in 2017, Deloitte found that 38 percent of millennials surveyed said they plan to leave their organization within the next two years.7

Connecting talent and strategy

At many low-performing organizations, talent and strategy are seen as separate channels. At many high-performing organizations, recruitment and retention and internal mobility are inextricably linked. These organizations expend meaningful effort and energy creating experiences and expectations for talent that encourage growth, learning, engagement, and communication. They spend far more time coaching and developing employees, creating cross-training and stretch assignment opportunities, and focus more on workplace values than on the kind of capabilities that can be claimed on a résumé. The goal isn’t merely to help an individual worker build a more certain career path. The goal is to give each worker a way to differentiate themselves as they move up within an organization—not all that different than an extended job performance review.

Organizations that excel at talent management and acquisition don’t seek out internal candidates merely to improve engagement and retention rates—although that’s usually a happy side effect, as on-the-job development opportunities such as lateral moves and stretch assignments can increase engagement by up to 30 percent.8 Rather, they are creating a relationship. These employers want to closely tie a worker’s long-term goals with the organization’s objectives and performance. As one progresses, so should the other.

A new approach to internal mobility

Transforming a culture to promote internal mobility should be seen as part of a larger, systemic approach to talent management. It begins with an awareness that one of the most effective ways to promote retention, career ambition, and internal mobility is to champion it at the highest levels and build it into the culture of the organization. But that takes a shift in mindset.

That can start by challenging the assumption that losing an employee, from a financial perspective, is a neutral event. It’s true that when employees leave, their salaries and benefits disappear from expenses and are reabsorbed into the bottom line, resulting in near-term savings. But those savings are quickly overwhelmed by other costs, both direct and indirect: for one, there’s the loss of productivity, institutional knowledge, and client relationships when an experienced employee leaves, not to mention the cost of recruiting and training a replacement. These costs do vary, based on industry, size of organization, and position. But we calculate that the departure of an average employee earning US$130,000 annually in salary and benefits results in a loss of US$109,676 based on lost productivity and the subsequent cost of recruiting and training a new hire. Consider the potential implications of such losses on an organization with 30,000 employees and a fairly typical 13 percent voluntary departure rate.9 The losses add up quickly—to more than US$400 million annually—and reducing voluntary turnover can have significant financial benefits.10

The cost may also extend beyond dollars. In an organization with heavy turnover, especially among high-potential performers, the impact on the company’s employment brand can be significant—and self-fulfilling. Call it the negative talent cycle: There’s no implied loyalty between employees and employers, so employers don’t want to invest in career planning and learning programs. Because there are no career planning and learning programs, employees don’t have the skills to be considered for promotion—and there’s no internal mobility. Because there’s no internal mobility, the very best employees keep leaving, hurting the organization’s brand in the career market. And the cycle begins again.

It's always better to focus on the bottom-line costs associated with hiring externally rather than from within. It demands a risk-adjusted approach to hiring—what’s the risk of hiring someone you don’t know well as opposed to looking at talent within the organization you do know? It’s no different than what happens at a flea market. The seller always knows the goods better than anyone else—and if you’re a buyer, it’s caveat emptor.

The same is true with talent. Employers have the seller’s advantage, as nobody knows their talent better. If an external candidate and an internal candidate both apply for a leadership position, whose résumé and job record can you trust more? The internal candidate has a demonstrated work history, manager reviews, and a verifiable list of accomplishments, not to mention deep familiarity with your organization’s culture, expectations, and strategy. The external candidate is, by comparison, a closed book. Even the most rigorous talent acquisition process, extensive interviews, testing, and reference checks can’t give you the same level of confidence that they’re ready for the job you need to fill.

And the numbers support this. Organizations that promoted internally are 32 percent more likely to be satisfied with the quality of their new hires.11 That’s because it typically takes two years for the performance reviews of an external hire to reach the same level as those of an internal hire.12 Compared with internal hires in similar positions, external hires are 61 percent more likely to be laid off or fired in their first year of service and 21 percent more likely to leave.13

So how should organizations seek to transform their approach to internal mobility? We view it across three dimensions:

Creating a culture of internal mobility

Executives should fully grasp the close relationship between talent and organization wide performance—and then view talent as a capital asset critical to growth. Recognizing talent as a precondition for performance helps leaders look at all aspects of talent acquisition and management as an ongoing part of doing business, rather than just a necessary cost.

With that recognition, the investments necessary to an overall culture of talent development can lead inevitably to greater internal mobility. For example, active programs in career “storytelling” help champion those who have climbed the career ladder—a sure way to reward outstanding performers and draw attention to them. But such programs also demonstrate in real and practical ways how younger workers can achieve the same level of success, which is an essential part of building a culture of internal mobility. Giving workers the necessary opportunities to learn and stretch assignments is one critical step; giving them a narrative they can model their own careers on is another (and especially important, because it helps raise the sights of those who might not otherwise believe they can move forward in an organization). That’s why long-term investments are able to create a stronger pipeline of talent through improved employment brand, higher retention, and more successful recruitment.

Consider Farm Bureau Financial Services, where the talent process was once highly reactive; recruiters scrambled to find candidates when jobs came open. While a new approach was needed, the company’s talent acquisition team looked beyond merely setting up internal job boards to seek to foster a culture that encouraged employees to drive their career journeys through advancement opportunities.14 It pushed workers to reflect on their performance, image, and exposure throughout the organization with the goal of developing a professional brand to open internal doors of opportunity. The result has been a far richer talent pipeline of internal candidates.15 Another example is Minnesota’s Mayo Clinic, where employees are encouraged to be lifelong learners and build career paths anchored by exploration and growth. Managers work with employees to explore ways to build capabilities and new experiences, and they are required to be familiar with career resources the company offers so they can promote those programs to employees. Mayo Clinic’s turnover rate is well below similar-sized organizations in health care, and it’s common for employees with 30-year tenures to have held multiple jobs.16

Gaining leadership support

Leaders should support a companywide goal of retention through internal mobility. Many of the highest-performing organizations explicitly set hiring targets for internal candidates and support those metrics by tying management compensation to making sure workers are building skills and gaining the kind of training that helps them merit promotion. Recruiters and hiring managers can work together to identify the qualities that will make for outstanding candidates for positions that are not yet open, so that capable or potentially capable candidates can be identified and prepared. In addition, recruiters and hiring managers should seek out the ambitions of employees and seek ways to satisfy those aspirations. The goal is a “pull-through” effect, where high-potential workers reach ever-higher levels within the organization, creating opportunities as well as examples for others to follow.

At Home Depot, which employs 400,000 people in stores across North America, leaders are squarely at the center of internal mobility efforts. The company encourages storytelling—leaders and managers describing their own career trajectories—to create models for more recent hires to emulate. It encourages associates to plan their careers, and to follow that path wherever it takes them inside the company, whether laterally or vertically. And, finally, leaders and managers are rated on their ability to fill talent pipelines with internal candidates so they participate on both the supply and demand sides.17

Reimagining human resources

The process for reshaping the HR function should be supported by a simple argument: You get more bang for your buck by recruiting and hiring internally. Though most companies spend only 6 percent of their recruitment budgets on internal candidates, these candidates fill 14 percent of job openings.18 It’s clearly an efficient way to find candidates, and bypasses other costs such as onboarding, company-specific training, and other upfront expenses associated with hiring from the outside.

There’s another demonstrated benefit: Organizations that are good at promoting from within are more likely to be effective at many other aspects of talent recruitment and retention. Three out of four of the leading talent acquisition teams, as measured by Bersin’s 2018 talent acquisition industry study, tap into internal talent pools, compared with roughly one in 10 low-performing teams. And these high-performing talent acquisition teams are five times more likely to offer a strategic approach to internal mobility.19

That strategic approach is reflected in a focus on worker experiences and building strong capabilities to deliver career journeys. This has multiple implications for internal mobility efforts. For example, in large, high-performing organizations, HR teams comprising learning and career management are increasingly working hand-in-hand with HR colleagues focused on talent acquisition.20 The idea is that those organizations focused on talent acquisition have a better understanding of the typical career journeys of high-potential, high-performing workers—and look for those qualities throughout the talent universe, both inside and outside the organization. For too long, talent acquisition has often been siloed and excluded from conversations around career management, promotion, and workplace culture, to the point where recruiters are often unaware that the best candidates for open positions are often already inside the organization. In high-performing HR organizations, talent acquisition sits at the center of those conversations so recruiters have a clear understanding of the kind of talent that can thrive, as well as the processes and technologies required to deliver it.

An effective transformation of HR’s approach to internal talent requires buy-in across the organization, especially in an age where teams are replacing hierarchies. Teams are a testing ground for potential leaders—in short-term assignments and focused projects, a team can be led by someone with very little management experience. This provides them a window into their own skills as a leader, and gives them a chance to shine. Managers and HR leaders should work together to use team-based structures to identify possible internal candidates for promotion and further growth opportunities. It’s not just about posting job openings and creating internal career mileposts. It’s about stretching workers’ imaginations, challenging them in real-life situations, and helping them see that they’re capable of more than they thought. This work doesn’t happen by itself, and HR will often have to take a leading role.

One global consumer goods company struggling with its employment brand set a new expectation that recruiters would have 48 hours to respond to internal applicants and 72 hours to conduct an initial screening—even if the applicant was not quite suited to the role. This simpler, streamlined process had an immediate impact, with employees feeling more connected and engaged with hiring teams and more likely to continue applying for posted roles. The organization’s initial target was to eventually fill 10 percent of all open positions with internal candidates, but within a year, it was sourcing 30 percent of hires from within.21

Now imagine a process that also turns a cold rejection for a role into a career conversation about how internal candidates can close identified skill gaps. This means that talent acquisition teams work hand in hand with career-management colleagues, which, in turn, need to work closely with their learning counterparts. The net result is all of HR working together to help make employees feel they are a valued part of the organization and don’t need to look externally in order to grow professionally and personally.

Taken together, acting across these dimensions can lay the foundation for a new kind of talent cycle. Instead of an absence of professional-growth programs leading to low retention leading to a damaged employment brand leading to poor recruitment, organizations can create a virtuous talent cycle: an employment brand defined by professional growth opportunities that attracts the very people who seek opportunities for promotion and growth—and who value it as much as, if not more than, what they’re paid. Inextricably linking culture, leadership, and HR can increase internal mobility and retention. But it takes specific efforts such as including the talent acquisition function, creating learning and skills programs, establishing career narrative-building, and investing in employee experience. The net result of these efforts can be an organization able to invest confidently in its own people. And just like buying back stock in its own growth story, the company knows exactly what it’s getting and why it’s confident in making the move.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.