Mexico: Uncertainty looms

01 February 2018

Uncertainty looms large over Mexico, as the stability achieved over the last 15 years could be threatened by several factors, the most crucial of which is likely the renegotiation of NAFTA. With presidential elections around the corner, Mexico will rely on a solid macroeconomic policy to navigate a rocky 2018.

Inflation and uncertainty around NAFTA could slow down growth in 2018

Learn More

Subscribe to receive our Economic Outlook emails

Subscribe to receive Public Sector content

The last 15 years have witnessed a period of macroeconomic stability previously unseen in Mexico. However, by November 2017, inflation had reached 6.6 percent on an annual basis.1 While the current spike is nowhere near the levels registered in previous decades, it is significant enough to warrant attention. The liberalization of the energy market, a depreciation of the Mexican peso vis-à-vis the dollar, and uncertainty regarding the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) have all helped contribute to the spike in inflation. As Mexico enters the new year, the stability achieved over the past decade or so may become fragile. The renegotiation of NAFTA looms large over the Mexican economy.

Inflation strikes back

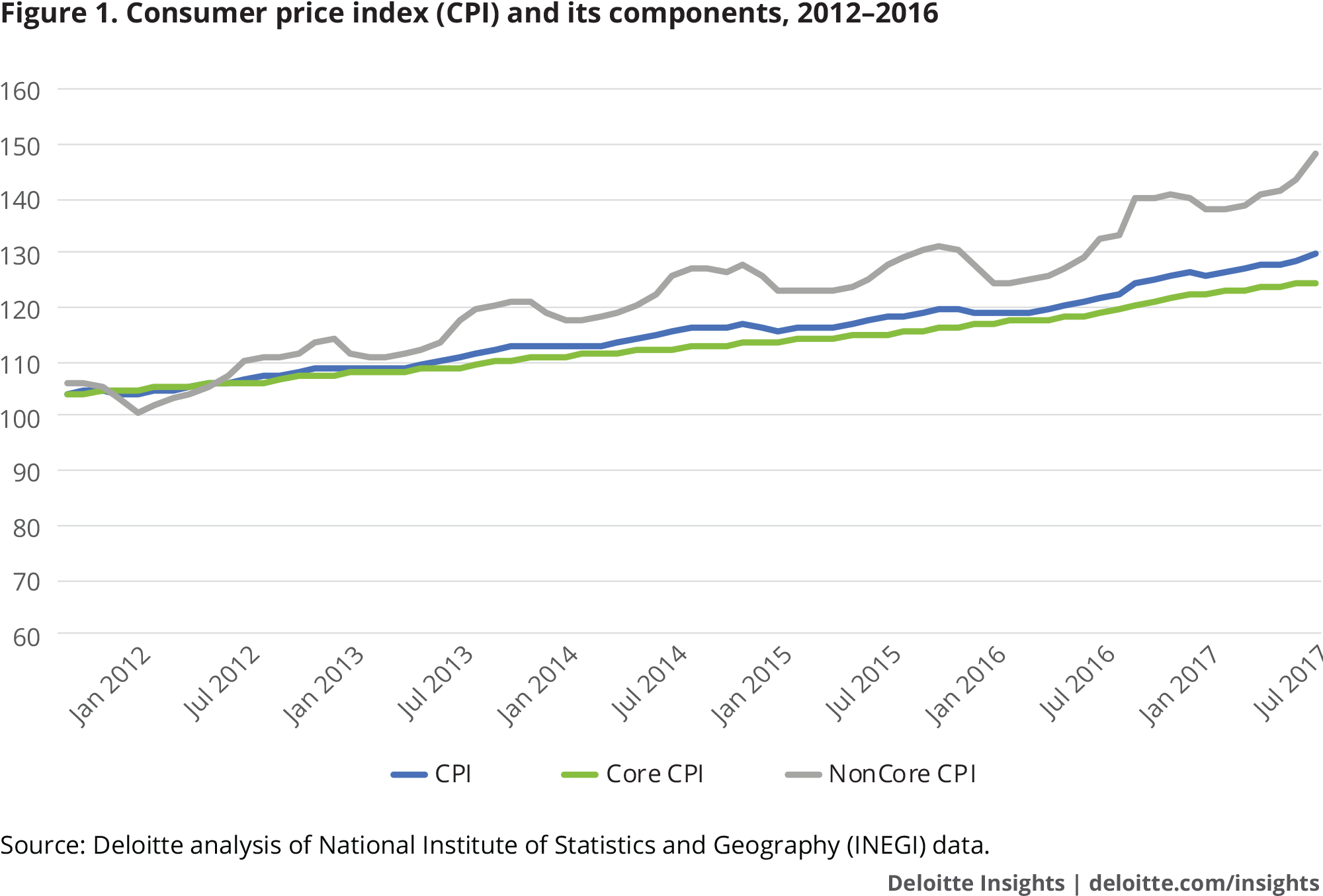

The 6.6 percent year-over-year inflation rate in November was almost double the average annual rate of 3.5 percent registered between 2012 and 2016. While core inflation posted a 4.9 percent rise, noncore inflation increased by a significant 12 percent.2 At first glance, these numbers appear alarming, but it is worth remembering that during the 1980s and 1990s, prices rose 44 percent per year on average.3 It wasn’t until the aftermath of the 1994 financial crisis that Mexico adopted robust monetary policies aimed at stabilizing the exchange rate and controlling spiraling prices.

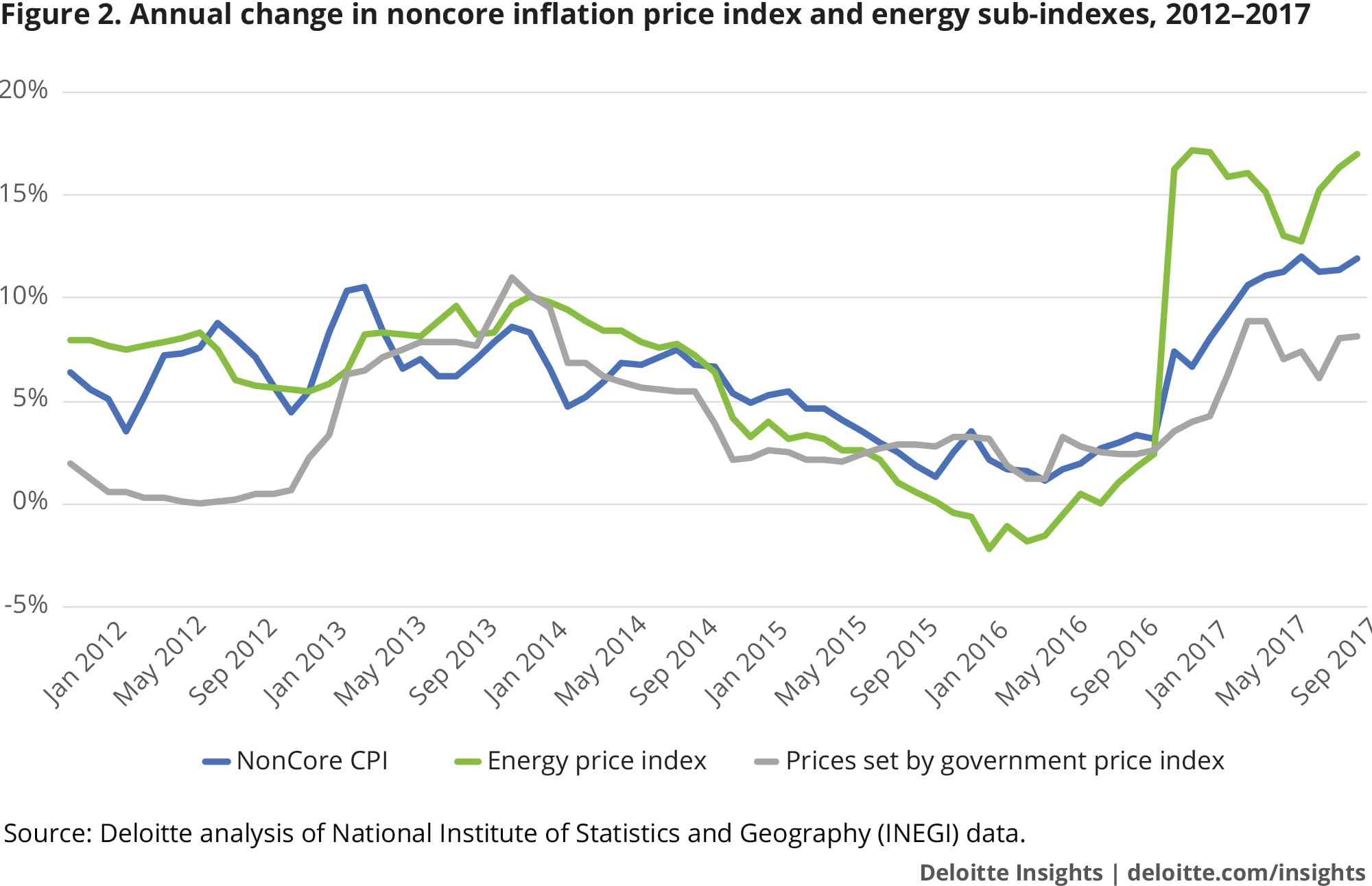

One of the main factors behind the recent increase in prices is the liberalization of gasoline prices in Q1 2017. The change in policy was part of President Enrique Peña Nieto’s marquee energy reform approved in 2013, which ended a 75-year monopoly on the energy sector.4 Besides opening markets for private investment, the initiative also ended a policy of fixed prices and eliminated subsidies for gasoline and other fuels. Given the early 2017 gasoline price deregulation, it is not surprising that the energy price index registered a 17 percent increase from the previous year. The prices approved by the government index (Energéticos y tarifas autorizadas por el gobierno), which captures the relative cost of other parts of the energy sector, also registered an annual increase of 8.2 percent.

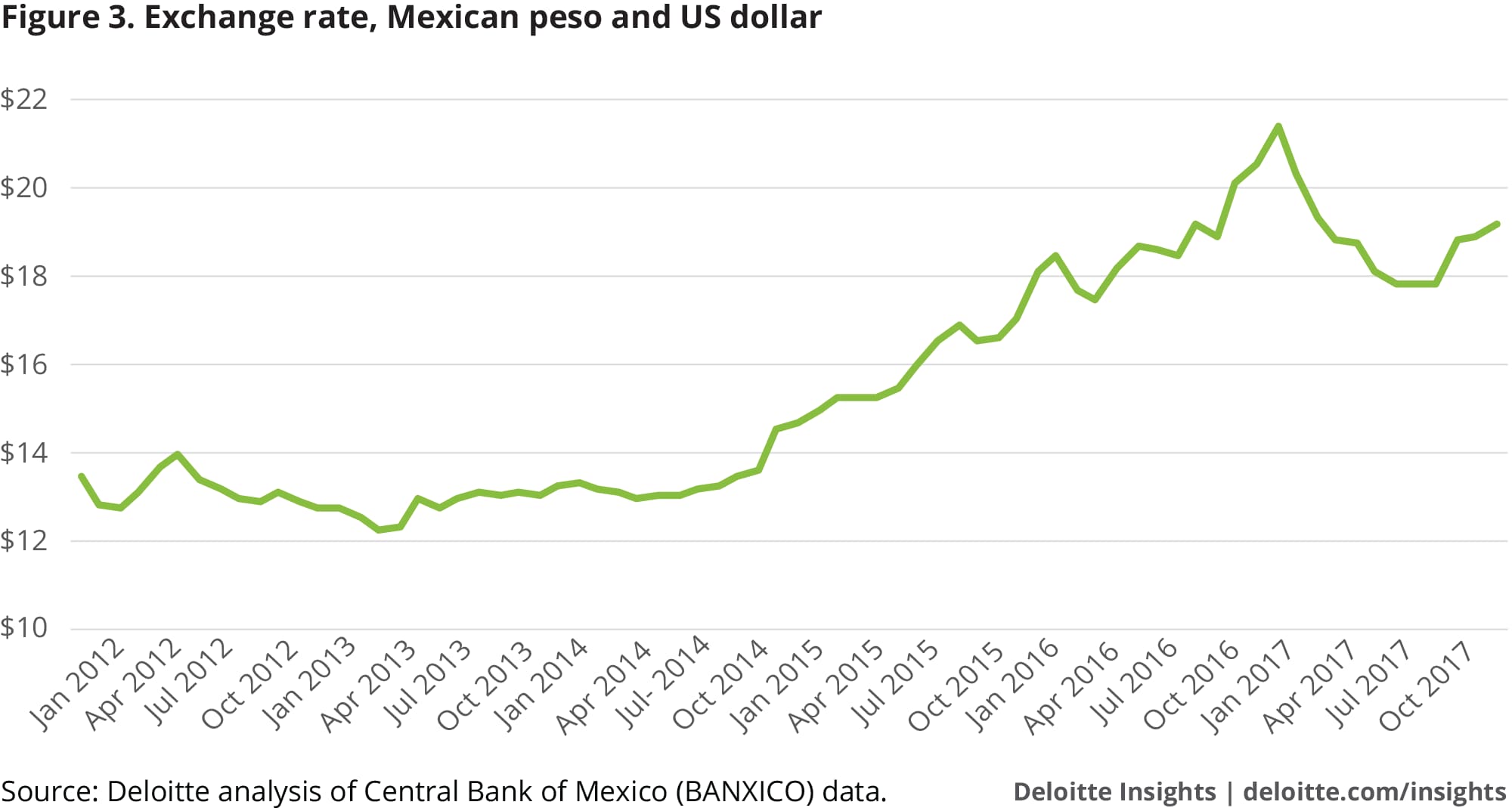

Alongside the rising costs of energy and fuels, the depreciation of the Mexican peso against the dollar―as of December 2017, the peso lost 12.4 percent of its value with respect to December 2015 levels―also contributed to higher prices of basic staples for Mexican consumers. Fruits and vegetables and meat and eggs posted annual increments of 14.9 percent and 5.2 percent, respectively.5 One of the often-overlooked aspects of the trade relationship between Mexico and the United States is the agricultural sector. In 2016, Mexico imported food and live animals worth more than $14 billion—76 percent of its agricultural and animal product imports—from the United States.6 About 43 percent of all the food consumed by Mexican households is imported;7 thus, variations on exchange rates have important effects on the inflation levels.

The Mexican government has responded to the inflationary pressure with higher interest rates, tighter monetary policy, and lower public expenditure. The policies have stopped the spiraling of prices and in some cases, the indexes are returning to their historical growth averages. But while these measures have been relatively successful, they alone will likely not be sufficient to curb inflation given the speculation around the future of NAFTA.

Renegotiating NAFTA

For the first time in modern history, the event that will likely have the largest impact on the Mexican economy will not be the election for a new president (scheduled in July 2018), but rather, the results of the NAFTA renegotiation talks. Many analysts credit the free trade agreement with spurring economic modernization in Mexico over the past decade, particularly in the manufacturing sector.8 The country’s stakes in successfully renegotiating the trade agreement is therefore high. However, the lack of substantial progress achieved in the five rounds of negotiation held to date suggests that some skepticism about the outcome of the negotiation is in order.

The latest round of negotiations held in October 2017 in Mexico City did not produce significant results.9 One of the most contentious points discussed is the demand from the US negotiators to increase the rules of origin for the automotive industry to 85 percent (from the current 62.5 percent), with at least 50 percent of US content.10 This is a critical roadblock given the prominence of the automotive industry for the Mexican economy. The industry now accounts for 3 percent of the country’s GDP, 18 percent of all manufacturing value added, and 27 percent of all exports.11 Mexican negotiators have stressed the importance that the agreement has for the US, Mexican, and Canadian automotive industries, hoping that the US negotiators would find common ground. But Mexican policy makers are also preparing for a scenario where NAFTA is terminated. The European Union and Japan could be alternative markets as Mexican exports could become even more competitive, thanks to a cheaper peso and Mexico’s other existing free trade agreements.12

Other aspects of the negotiation that have resulted in disagreements between the negotiating parties include minimum wages and work conditions of Mexican manufacturing workers, a provision that would end the agreement after five years unless all the participants agree upon its renewal, participation of Mexican and Canadian firms in US government contracts, elimination of a trade dispute resolution mechanism, and restrictions on produce and agricultural goods.13 These remain salient and delicate points and could derail the negotiations, potentially leading to an abrupt end of the 24-year-old trade agreement.

An abrupt exit will place additional pressure on the Mexican economy, particularly around foreign direct investment in a context of fiscal reform in the United States.14 However, with a unique geographic advantage, a free-floating currency that can adjust to make exports attractive, relatively cheap labor, and competitive transnational supply and production chains, Mexico can remain competitive in the manufacture of goods in a post-NAFTA scenario.

Looking forward to 2018

The inflationary spike resulted in a tightening of public expenditure as well as an increase in the target interest rate by the Central Bank of Mexico to 7 percent, the highest level since the 2008 financial crisis. It is expected that this rate will be held at this level for the majority of the first half of 2018. As a result, investment and consumption have been affected, and the International Monetary Fund has lowered its GDP growth forecast for 2018 to 1.9 percent, down from the 2.0 percent projected in April 2017.15

While the fate of NAFTA will probably be the most central development affecting the economy, the elections may bring additional uncertainty to the Mexican economy. The Mexican business community is concerned that a victory by the populist leftist candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) could harm the country’s economic prospects,16 and that his perceived protectionist stance could lead to a further depreciation of the peso.

While the Mexican economy has a complicated road ahead, the solid macroeconomic basis that policy makers have built over the last 15 years as well as their competitive manufacturing sector should help the Mexican economy navigate the turbulent first half of 2018.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.