Monetary policy in Asia Proactive so far, but faced with uncertainties

10 minute read

04 December 2020

Central banks are facing the unavoidable dilemma—short-term growth may come at the cost of soft long-term fundamentals, yet if they hold back now, the recovery may not sustain.

As Asia tries to find its way through the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers have been quick to step in with much-needed economic support. While the fiscal side has focused on immediate health-related requirements and short-term economic support, monetary policy has taken up the twin roles of stimulating demand and stabilizing credit markets. Through interest rate cuts and liquidity measures, Asian central banks have tried to counter the declining economic activity in the first half of 2020.1 Encouragingly, the tide seems to be turning with consumer spending and manufacturing showing signs of revival across the region. Yet central banks’ worries are far from over given the course of the pandemic itself.2 And while a proven vaccine is expected to be available by late 2020 or early 2021,3 its deployment will take time given the large population in Asia and the logistics involved in vaccine deployment.4 Evidence from Europe and the United States suggests that another wave of infections may have started,5 serving as a grim reminder regarding the unpredictability of the pandemic. Monetary authorities in Asia’s emerging markets may also have to contend with currency weakness given investors’ preference for safe assets during this global uncertainty. And increased price pressures due to localized lockdowns may only add to central banks’ woes.

Asian central banks have responded proactively to dent the downturn

Learn more

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

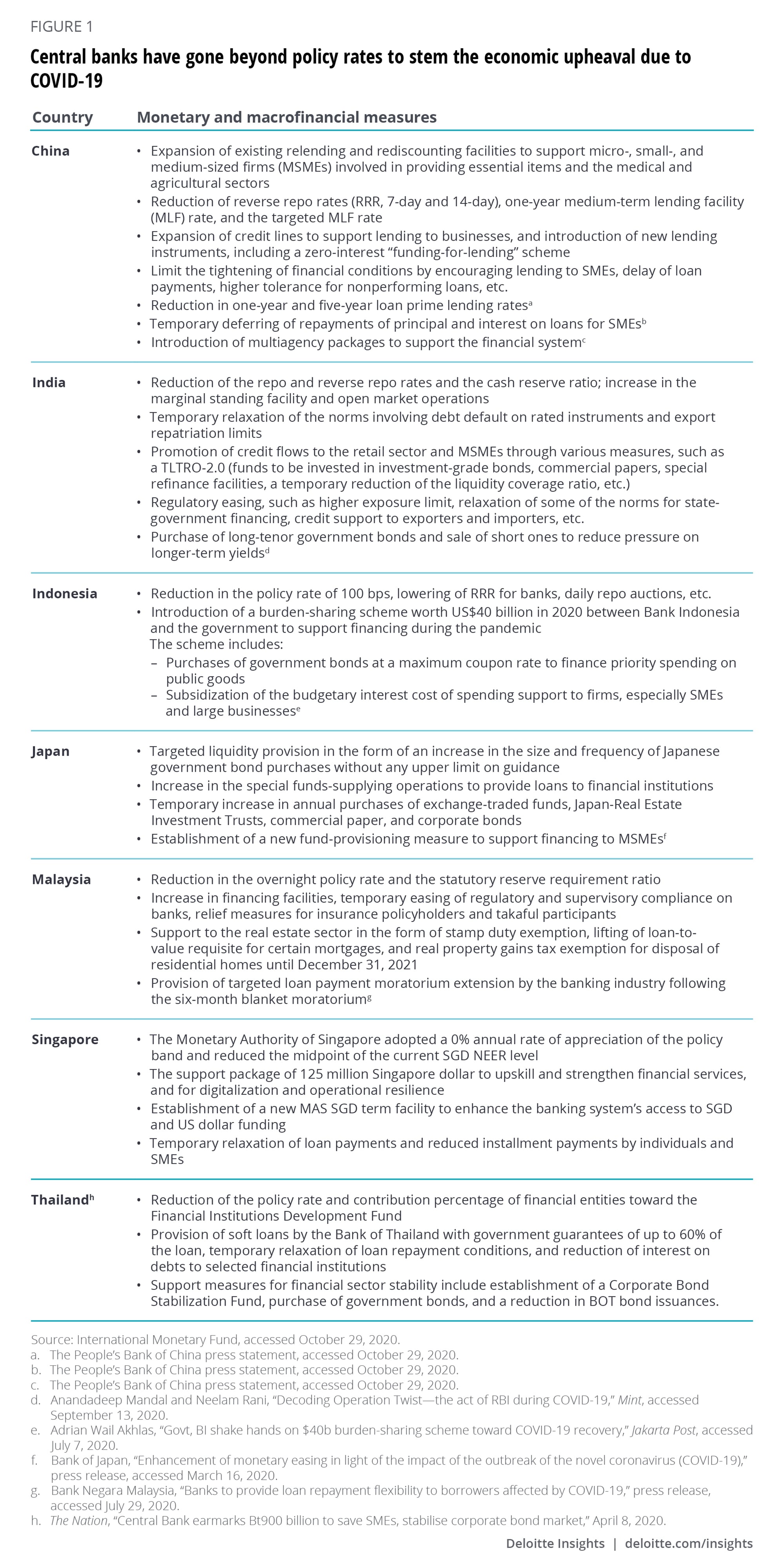

As in previous economic crises, central banks in Asia have used policy rates6 as a key tool to ease financial stress and stimulate growth. They have cut rates and lowered reserve requirements for commercial banks to support credit growth. That’s just one part of the monetary response so far (figure 1). Monetary authorities have also indulged in unorthodox measures, such as nudging financial institutions to keep extending credit, encouraging credit flows to key sectors, establishing financing facilities, and ensuring adequate collateral for financial institutions. And like their counterparts in Europe and the Americas, central banks in Asia have been acting as a bridge between governments and financial institutions to provide additional lending support even as they ensure liquidity in fixed-income markets through government bond purchases.

Economic activity is recovering, but uncertainty remains

As countries learn the ropes of the pandemic, and with fiscal and monetary measures playing their part, economic activity is slowly reviving. China has been leading the way with healthy GDP growth in the second and third quarters of the year. While Vietnam and Taiwan had relatively steady growth in Q3 2020, the pace of contraction has lessened in South Korea. High-frequency data on consumer spending and manufacturing also points to improvement across the region. In India, manufacturing activity as indicated by the purchasing managers’ index swung back into growth since August while in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) bloc, activity has been slowly picking up since March.7 Consumer spending also seems to be bouncing back with the value of retail sales rebounding from lows between March and May. In China, for example, retail sales in September were 13.3% higher than in March; while in Vietnam, sales in October were up by nearly half compared to April.

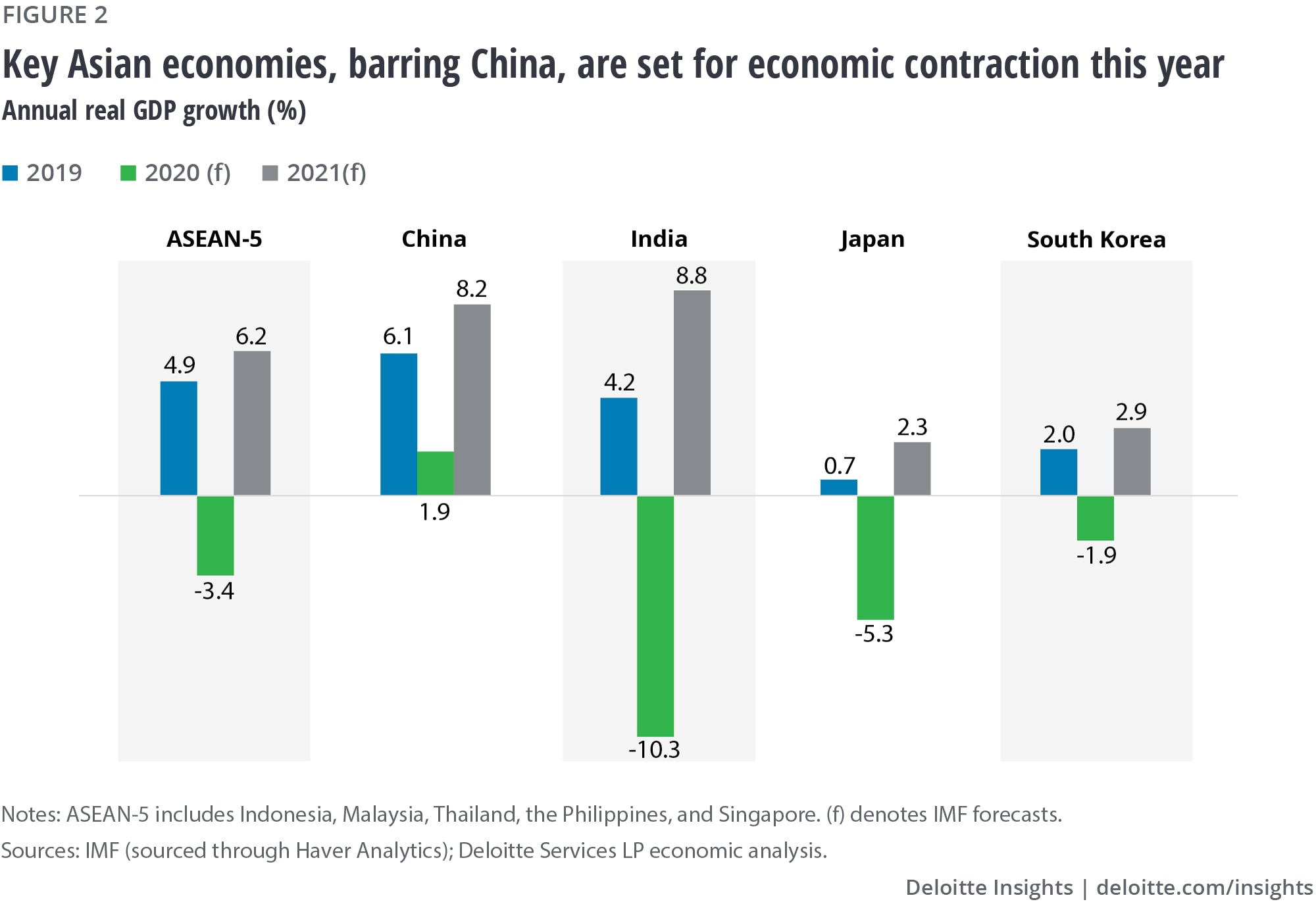

The extent and duration of the revival in economic activity, however, is uncertain given the current course of the pandemic and that a proven vaccine will likely come in only by late 2020 or early 2021.8 And even when a vaccine is made available, it will take time before the vaccine can be administered to most of the population.9 So, sectors such as aviation, tourism, and hospitality will continue to face pressures, especially with highly restricted international travel. In Thailand, a key tourist destination, foreign tourist arrivals are down to zero from 3.8 million in January. A similar trend—albeit with some variability—is also evident in countries like Malaysia and Hong Kong. The economic recovery, therefore, is unlikely to be uniform across sectors and economies. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), emerging and developing Asia10 is expected to contract by 1.7% in 2020 despite a 1.9% rise forecasted for China; growth in India is set to fall the most among notable economies in this bloc.11 Advanced economies like Japan and South Korea are also expected to contract this year (figure 2).12 Such a scenario points to continued involvement of central banks in reviving growth into 2021.

Moderation in inflation pressures in most economies will aid monetary policy

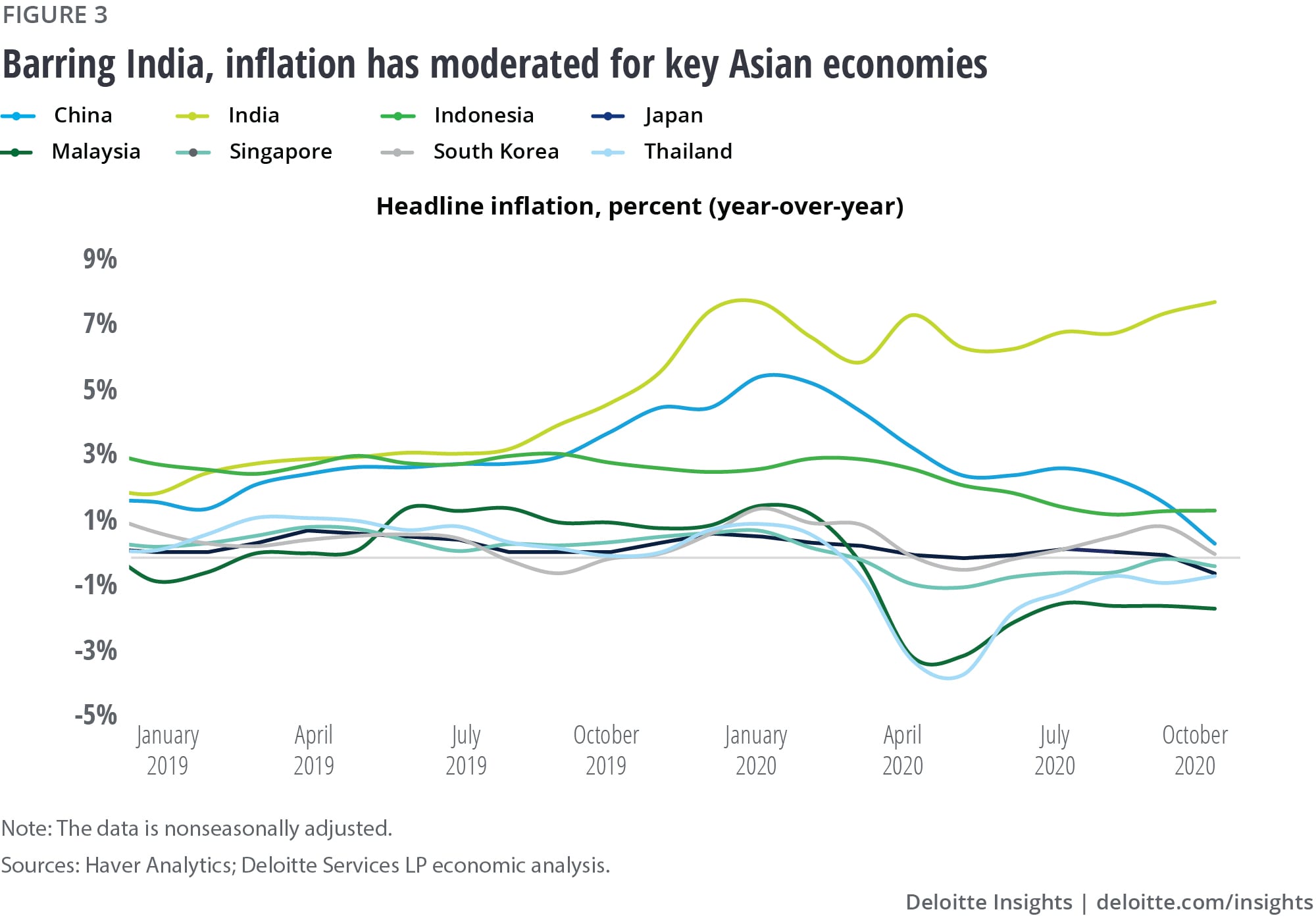

The strong dent in economic activity has led to an overall moderation in inflation across major economies in Asia (figure 3). A hit to demand for certain consumer goods has impacted goods prices, while services inflation, especially in recreation and transportation, has dropped. Consequently, core inflation has moderated in key Asian economies, barring India. In Malaysia, for example, low core inflation is attributed to the softening of prices of clothing and footwear, and transportation. Weak energy prices have also weighed on overall inflation since the start of the year. In Singapore, for example, prices of fuel and utilities fell by 9.6% year over year in Q3 2020; while in Thailand, energy prices fell by 10.5%.

Moderation in inflation augurs well for monetary policy as it leaves central banks more room to revive growth. For the Bank of Japan (BOJ), however, the fall in aggregate demand and energy prices will be a cause for concern as it may complicate the long fight against deflationary pressures through strong quantitative easing. Other central banks will likely remain wary of any supply-side push on inflation as happened during the early stages of the pandemic when disruptions in supply chains pushed up prices of certain consumer goods. In India, supply-related issues have aided food and beverage inflation, which in turn has pushed headline inflation above the Reserve Bank of India’s upper level of the target range13 for six straight months. In China, too, food inflation averaged 18.3% year over year between February and April. It is likely, however, that food-related inflation will slow as economies open further and supply chains function more smoothly than in the initial months of the pandemic. While that hasn’t happened in India yet, the latest data suggests that food inflation has slowed in countries such as Indonesia and, to a lesser extent, China.

Don’t forget them currencies

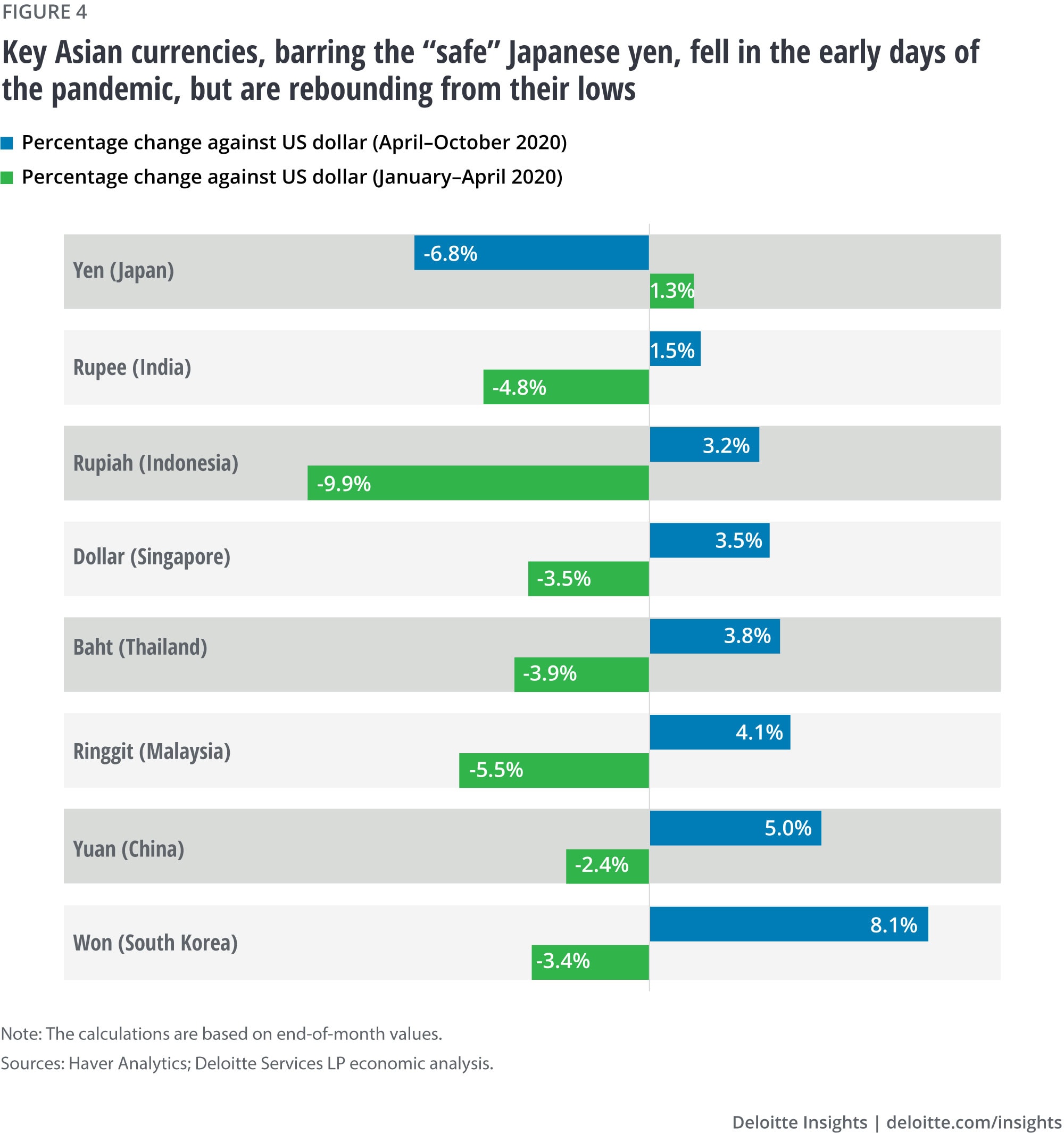

The start of the pandemic and its initial economic impact predictably put pressure on key Asian currencies due to a global rush toward safe assets such as the US dollar. Apart from the Japanese yen, again a safe asset, the plunge in most Asian currencies started in February, reflecting investors’ concerns at that time about deteriorating economic and financial fundamentals as COVID-19 spread globally (figure 4).

While cutting interest rates may have posed a worry for Asian central banks due to depreciating currencies, what has worked well is that advanced economies have also eased policy. That has lessened the impact of interest rate differential between Asian currencies and, say, US currencies. And with central banks in advanced economies expanding their balance sheets sharply, a revival in economic activity in Asia means that global liquidity is likely to flow back to the region, thereby aiding currencies. Indeed, since May, Asian currencies have recovered (figure 4), buoyed by a nascent economic recovery and uptick in financial markets.

However, it is too early to say that the phase of currency depreciation is over. A surge in infections in Europe and the United States in late October has impacted global financial markets, reinforcing the uncertainty about the pandemic. Any rise in global uncertainty may topple the currency apple cart, thereby making further monetary easing difficult for Asian central banks other than the BOJ.

There’s a limit to monetary firepower

While central banks have been proactive in countering the downturn and have acted in tandem with fiscal authorities, there is a limit to how much they can do. Central banks will also be wary about the impact on debt from strong monetary support. For example, household debt in some Asian economies surged after 2008 due to a credit-driven expansion.14 Similarly, in China, the overall debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to reach 335% in the upcoming months.15 That’s not all. Central banks will also be wary about deteriorating fiscal balances as governments provide desperate support to their economies. In India, for example, the general government debt-to-GDP ratio has risen by 17% so far this year compared to 2019.16

Business bankruptcies will also likely worsen if the economy doesn’t rebound fast, thereby putting strain on banks’ asset quality. According to Moody’s, by 2022, nonperforming assets in banking will likely double on average across 14 Asia-Pacific economies.17 In this scenario, a low-interest-rate ecosystem will only add to banks’ woes due to lower profitability.

There are difficult choices ahead for monetary policy in Asia: Focus too much on short-term growth and see long-term fundamentals deteriorate, or hold back now and risk jeopardizing the current recovery. Clearly, it’s an unenviable task to be a central banker in these times.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more on the Economics collection

-

Eurozone economic outlook, September 2024 Article7 months ago

-

Brazil economic outlook, March 2025 Article1 month ago

-

G7 economies Article4 years ago