Ring in the new: Holiday season e-commerce sales poised for strong growth has been saved

Ring in the new: Holiday season e-commerce sales poised for strong growth Behind the Numbers, September 2016

22 September 2016

Although classification issues make it difficult to find recent and detailed information on e-commerce sales, indications show it is growing fast. And in the upcoming holiday season, we expect e-commerce sales to grow 17–19 percent.

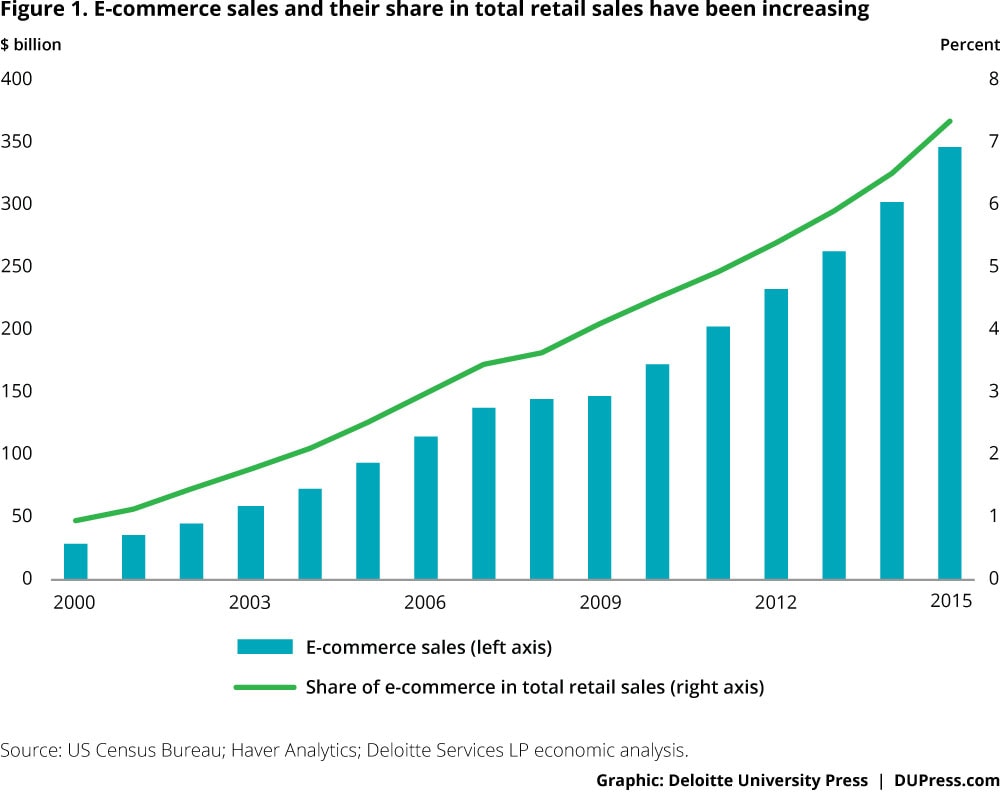

E-commerce has been a big disruptor of traditional retail sales. Buoyed by innovations in technology and demographic changes, e-commerce sales have soared in recent years. In 2000, e-commerce sales were just $27.6 billion; by 2015, that had shot up to $343.0 billion, an average annual growth of 18.3 percent.1 In those 15 years, the share of e-commerce sales in total retail sales went up to 7.3 percent from just 0.9 percent (figure 1).

What does “e-commerce” mean?

Explore

View the Behind the Numbers collection, a monthly series from Deloitte’s economists.

The Census Bureau defines e-commerce sales as “sales of goods and services where the buyer places an order, or the price and terms of the sale are negotiated, over an Internet, mobile device, extranet, electronic data interchange network, electronic mail, or other comparable online system.”2 E-commerce sales represent a subset of overall retail and food services sales in the United States, which are calculated by the Census Bureau through a stratified random sampling of firms in the sector.

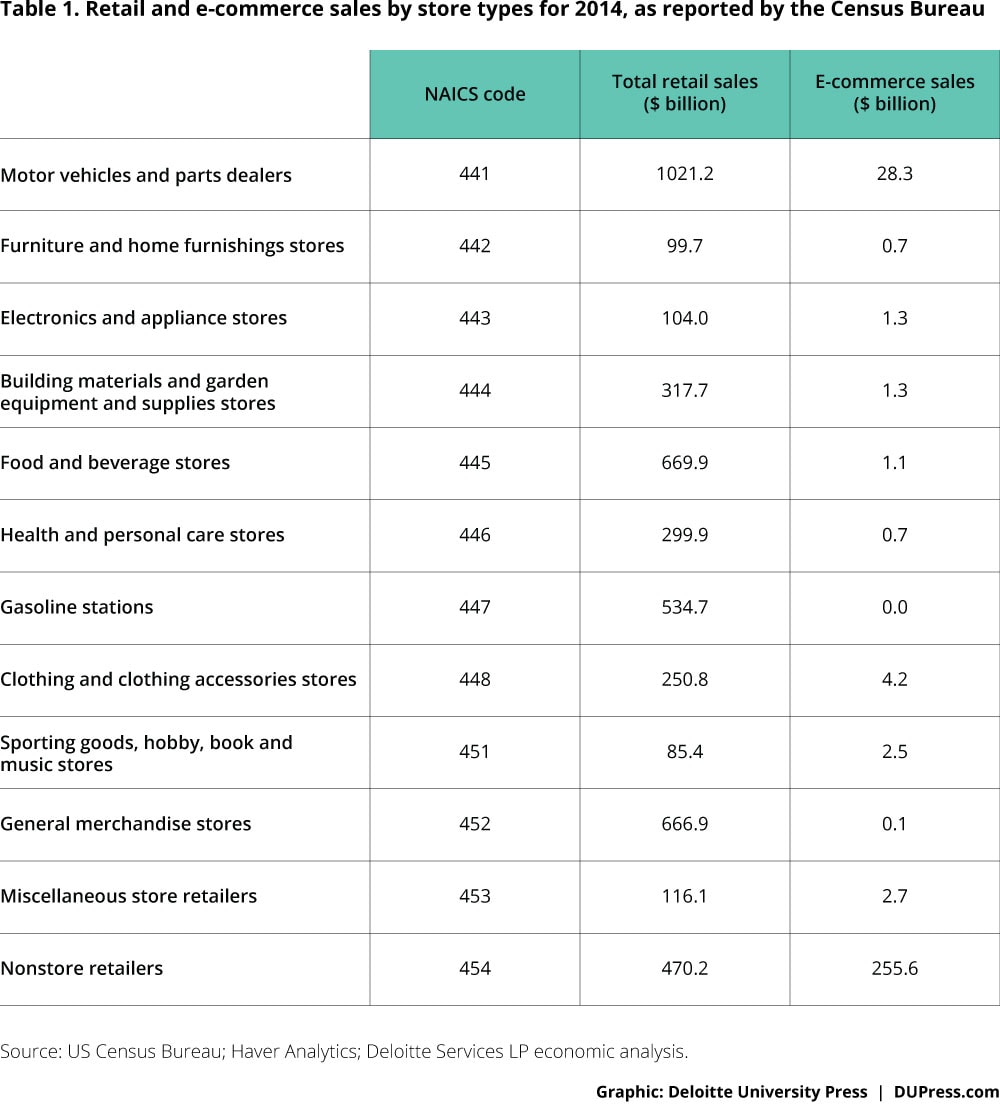

Overall retail and food services sales are classified by type of stores, which are organized according to the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS).3 However, detailed information on e-commerce sales is less readily available. Unlike data on aggregate retail sales, e-commerce sales data are released only on a quarterly basis, and these data are not classified by store types. E-commerce sales by store type are only available on an annual basis from the Census Bureau’s Annual Retail Trade Survey, and the data are classified only by major store type. Unfortunately, too, these annual reports on e-commerce sales are unavailable for years after 2014.

There are also some gaps in the data. Sales by certain store types are not available in some years, either due to high sampling variability or sales estimates being less than $500,000.4 E-commerce sales from gasoline stations (NAICS 447) is a good example of this. Moreover, the Census Bureau does not provide data on e-commerce sales at food services and drinking places (NAICS 722).

With the difficulty of finding data on e-commerce sales per se, one might think that the non-store retailers category could be a useful proxy for e-commerce. However, sales at non-store retailers may not be a good proxy for e-commerce sales for two reasons. First, non-store retailers include mail-order prescription pharmaceuticals, which is not e-commerce according to the Census Bureau definition. Second, non-store retailers also include fuel dealers. Sales there depend on oil prices (and heating degree days). Although fuel sales are only about 15 percent of total non-store sales, the high volatility of this series can introduce substantial noise into the aggregate non-store sales measure.

With all these caveats in mind, table 1 shows the major store types for retail and e-commerce sales, the NAICS codes for store types, and corresponding sales figures for 2014.

Our holiday season forecast: E-commerce sales to grow by 17–19 percent

Each year, Deloitte’s economics team forecasts holiday season retail sales. Here, we examine the specific contribution of e-commerce to holiday retail sales.

Deloitte defines the holiday season as the period from November to January. For the purpose of the holiday season forecast, Deloitte defines retail sales as total retail and food services sales excluding sales at gasoline stations and motor vehicles and parts dealers. We exclude both from our definition of e-commerce sales as well. Given that the Census Bureau does not give figures for e-commerce food services sales, we also exclude that component in our definition of e-commerce sales.

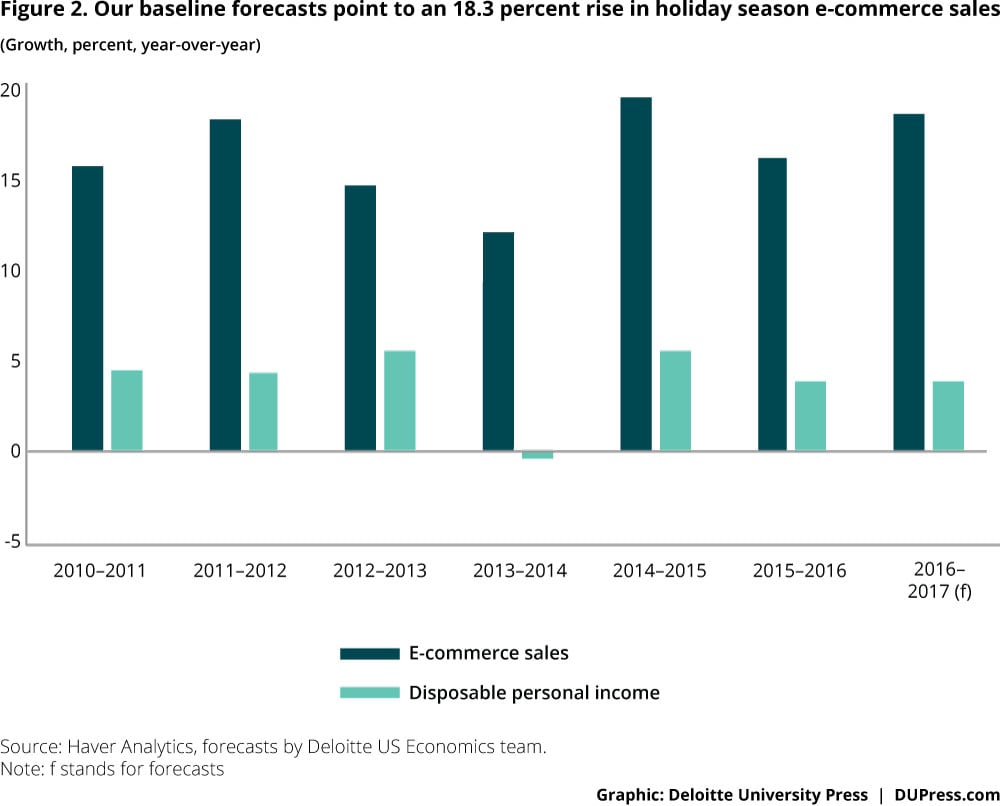

Our e-commerce sales forecast is based on our forecast of disposable personal income in Deloitte’s US Economic Forecast for the period from August 2016 to January 2017.5 Based on the model described below (see sidebar “Methodology for forecasting holiday retail sales”), we expect e-commerce sales for the upcoming holiday season (November to January) to grow 17 to 19 percent year-over-year to $95.5–97.5 billion. In the previous (2015–2016) holiday season, e-commerce sales went up by 15.9 percent, according to our estimates.

The anticipated rise in e-commerce sales growth in the upcoming holiday season can likely be attributed to three factors:

- Consumers have been resilient this year, primarily due to further strengthening of the labor market. In Q2 2016, for example, real consumer spending grew by 4.4 percent, the fastest pace since Q4 2014. The momentum, as reflected in retail sales through July, has continued through much of the summer.

- We expect marginally higher growth in disposable personal income in the upcoming holiday season compared to the previous year.6

- Consumers have also been digging into their savings. During the last holiday season, the savings rate averaged 6.1 percent. By July, the figure had fallen to 5.7 percent. Thus, sales have been slightly faster than we might expect given the growth in income.

Growth in total retail sales will also most likely be driven by the factors mentioned above. Our model for total retail sales predicts holiday season retail sales to grow by 3.6–4.0 percent. Retail sales had increased by 3.6 percent the last season. For more details, read our holiday season retail sales forecast.7

That said, several factors could negatively impact our forecast:

- Consumers could increase savings back toward the medium-term average of 5.9 percent. Spending would then grow more slowly than expected.

- Rising health care costs could restrain spending. The Kaiser Foundation estimates that insurance companies are requesting an average increase of 9 percent for plans on Health Exchanges.8 While most consumers do not buy insurance through exchanges, higher premiums and deductibles could reduce income available for spending at the end of this year.

- There are some signs that the strong job market is beginning to push up wages. Higher wages might give a larger bump to consumer spending than we are forecasting.

If our forecast holds, the continuing growth of e-commerce in the holiday season emphasizes a shift in consumer behavior to embrace e-commerce as a normal and expected method of shopping.

Methodology for forecasting holiday retail sales

Step 1. Estimating monthly e-commerce sales from annual data

We started by estimating monthly figures for e-commerce sales by store types using annual data. To do that, we first calculated, for each store type, the share of its e-commerce sales in its total retail sales. For example, for electronics and appliance stores, we calculated their e-commerce sales as a share of their total retail sales. Next, we checked trends in shares for each store type. We found that store types differed in the time periods over which trends are visible. Clothing and clothing accessories stores, for example, displayed a trend over 2007–2010, while for miscellaneous store retailers, the trend period was 2008–2014.

Using annual change in shares for each store type over its trend period, we projected shares for 2015 and 2016. For a few store types, we used 2014 shares for the next two years, given the absence of any trends (see table 2).

Next, we interpolated these annual shares for store types into monthly ones. Finally, we multiplied the share for each store type by the total retail sales for that type to arrive at estimates for monthly e-commerce sales by store type until July 2016. Adding e-commerce sales for all store types, except motor vehicles and parts dealers and gasoline stations, gives us total monthly e-commerce sales as per Deloitte’s definition (figure 3).

Step 2. Using a time series model to forecast holiday season e-commerce sales

Economic theory provides us with a rich set of models to analyze retail sales. We tested a number of key variables for forecasting ability using a holdout period of 2011 to 2014, and found that a simple model of spending based on disposable personal income forecasted at least as well as more complex models. We ran the same tests for both forecasts—aggregate holiday season retail sales and e-commerce sales. We started with an error correction model (ECM) for both sets of forecasts. While the ECM worked well for the holiday sales forecasts, we found out that for e-commerce sales, a distributed lagged model gave us better results. The model that forecasts e-commerce sales uses current and three-month lags of disposable personal income as the explanatory variables.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.