The value of resilient leadership Renewing our investment in trust

12 minute read

08 October 2020

Challenges for leaders won’t end with a COVID-19 vaccine. With many stakeholders already questioning their social contract with institutions, how can leaders invest in, rebuild, and renew trust in these relationships?

“The pandemic represents a rare but narrow window of opportunity to reflect, reimagine, and reset our world to create a healthier, more equitable, and more prosperous future.”—Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman, World Economic Forum1

Rebuilding the foundations

Our challenge as leaders won’t end with a COVID-19 vaccine. Underlying societal issues that have long been simmering below the surface are raising questions and imperatives that will last long after a COVID-19 inoculation is developed. The implicit social contract between institutions and stakeholders is rightfully being questioned. Individuals are frustrated; many don’t believe they are being heard by their leaders in government or by corporate institutions—or being treated fairly and equally.

Learn more

Explore more resources for resilient leaders

Learn about Deloitte’s Future of Trust services

Learn more about connecting for a resilient world

As recent research indicates, these trends were already latent, and just accelerated by COVID-19. For example, according to the Edelman Trust Barometer, 77% of US respondents (as of February) strongly or partially agree that large companies have been guilty of making a quick profit;2 the May 2020 update indicates that just 38% of global respondents believe that business is “doing well or very well” at putting people before profits.3 Further, millennials’ belief that business is “a force for good” continues to decline: Just 51% of millennials say business is a force for good, a steep drop from 76% three years ago. Amid the pandemic, only 41% of millennials feel that business is making a positive societal impact globally.4 Trust has fractured across government, business, and other pillars of society; the social contract has frayed—and continues to deteriorate further.

The challenges we are facing today are occurring against a backdrop of mistrust. When people trust each other, however, they work together more effectively and handle conflicts more maturely. In business, leaders are better able to create loyalty and confidence among stakeholders—their employees, customers, and ecosystem partners—and solve problems more quickly. In society, trust is the social glue that creates a sense of community cohesion. Therefore, rebuilding the world’s economy, our health and safety, our climate, and human relationships requires a renewed commitment to trust.

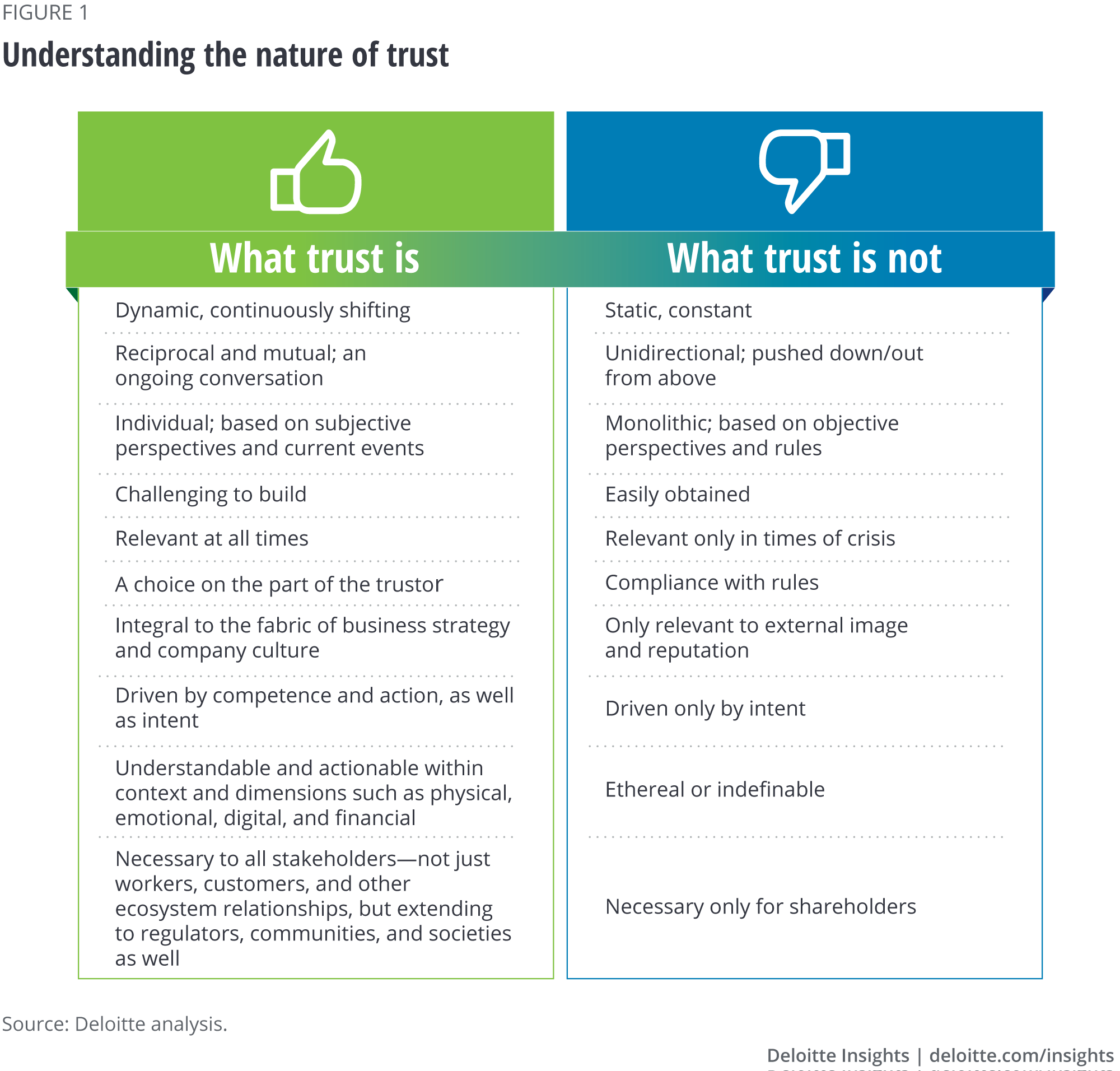

Trust is not a static, unchanging force that flows toward leaders from their stakeholders. Both trusting and being trustworthy require us to make conscious, daily choices to invest in relationships that result in mutual value. Trust is a tangible exchange of value, and it is actionable and human across many dimensions.5 Let’s examine how we can invest in, rebuild, and renew trust.

Defining trust

Trust is defined as “our willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of others because we believe they have good intentions and will behave well toward us.”6 We are willing to put our trust in others because we have faith that they have our best interests at heart, will not abuse us, and will safeguard our interests—and that doing so will result in a better outcome for all (figure 1).

Leaders can build and maintain trust by acting with competence and intent.7 Competence refers to the ability to execute, to follow through on what you say you will do. Intent refers to the meaning behind a business leader’s actions: taking decisive action from a place of genuine empathy and true care for the wants and needs of stakeholders.

Trust as an exchange of value: Why trust matters to resilient leaders

“Trust is … one of the most essential forms of capital a leader has.”—Francis Frei

While trust is considered by some to be an ethereal concept, it is, in fact, quite tangible. Therefore, we as leaders need to have a concrete way to talk about and act on trust for all our stakeholders: customers, workers, suppliers, regulators, investors, pension holders, society, and the communities we serve.8 In this regard, we can think of trust as an exchange of value, as a currency. Consider a 20 euro note: In isolation, it is just a piece of paper, but in an exchange, it represents everything from a plate of fish and chips to a birthday gift. Likewise, trust “banked” by itself has no intrinsic value, but when invested wisely by us as leaders in relationships with stakeholders, it enables activity and responses that help us mutually rebuild our organizations and society. At the same time, however, that currency must be nurtured through ongoing transparency and evidence of trustworthy behaviors, not simply saved to spend on excusing bad conduct.

As an asset, trust appreciates when it is invested well (and when it is continuously invested in). For example, in the United States, National Collegiate Athletic Association basketball teams that trusted their coaches were found to win 7% more games than those that did not.9 In essence, when coaches invested in building trust, players invested by playing better, resulting in a better outcome for all. In business, public companies rated the most trustworthy have been found to outperform the S&P 500.10 Further, high-trust companies “are more than 2.5 times more likely to be high-performing revenue organizations” than low-trust companies.11

The reverse is also true, however. Although the currency of trust is painstaking to accumulate, it can depreciate all too easily. As leaders, we know that failure to invest in trust, and to respond adequately or authentically to ongoing external crises (such as COVID-19), broader societal issues such as climate change or racial injustice, or any other organization-driven breach in trust, can lead to significant risk to the organization’s brand, its reputation, the well-being of its stakeholders, and its overall mission. Ultimately, stakeholders—whether customers, workers, individual investors, pension holders, communities, or ecosystem relationships—will be more likely to defect to a competitor when the opportunity becomes available if they don’t trust the organization. 12 Eighty-five percent of customers chose brands they highly trust when given the choice of other brands, compared with only 60% who selected brands that lacked their trust, while employees who highly trusted their employers were far more motivated to work.13 In fact, loss of reputation—i.e., the trust individuals have in the quality of one’s character, reinforced over time—is viewed as having the greatest risk-related impact on business strategy.14 Put simply, loss of trust can affect more than the simple measure of revenue; it can affect the intrinsic value of the organization.

Exchanges in trust and vulnerability go both ways

We sometimes treat trust as a one-way, top-down street: “If they trust us, they will follow us and believe in our mission.” But this approach presumes that trust is unidirectional, transactional, only based on what leadership does, and that “following” is tantamount to genuine commitment. It also suggests that leaders know better than their stakeholders—and that they need never make themselves vulnerable in the interchange.

Trust, however, is best fortified when there is a “balance of payments” between the two key elements in the definition of trust: vulnerability and response. We expect vulnerability from our stakeholders, and we respond to their needs, but we must be vulnerable in return as they react to our actions. Focusing only on our own commitment to being trustworthy overlooks the vulnerability we must manifest in the exchange. When trust flows in both directions, the stakeholder becomes a vested participant in the success of the organization, not merely a follower. Take, for example, trust among partners and a commitment to each other’s mutual success, as demonstrated by the vendors who are implementing new financing services to assist cash-strapped supply chain partners in the current COVID-19 environment.15 However, not all stakeholders feel they are trusted: Roughly 40% of millennials and Gen Z workers don’t agree that their employer trusts them to be productive in a remote environment.16

Trust encourages a mutual journey

Today’s economic realities are bringing the power of mutual trust to the fore: In some industries, massive layoffs are occurring, or more contract workers are being leveraged; in other industries, automation is on the rise. Those who remain with the organization need to trust that their leaders are committed to both the performance of the company and the career of the professional. This trust also affects longer-term focus areas for the organization, such as innovation: As companies adopt advanced technologies, workers are less likely to commit their minds, energy, and hearts to exploring the possibilities of these new technologies if they are unsure of the impact (such as automation) on their place in the organization. The same holds true for other stakeholders, both direct and indirect, who may be more likely to believe in the organization’s future plans when it’s an enterprise they know they can trust.

This ecosystem of stakeholders can amplify and extend the value of trust. As leaders, we have the opportunity, particularly during the current pandemic, to do more relationship-building as well as more collaborating across stakeholder groups. At the same time, however, many leaders are not yet harnessing the full power of trust across their whole system of stakeholders. We were surprised, for example, that in Deloitte’s most recent climate change survey, only 3% of business leaders said that collaborations among stakeholders (including government, activists, and nonprofits) rather than business leaders and/or other stakeholder groups working on their own will be most successful at making progress on the issue of environmental sustainability.17 For those who accept the premise that the whole stakeholder ecosystem can be engaged to address big challenges, those who can extend trust throughout their networks are perhaps best poised to make the biggest impact.

Driving real, valuable change

Many organizations will have to make major shifts in their business models in a post-COVID world, shifts that will require stakeholders to accompany us into unknown territory. Where do you need to invest further in a mutual journey of trust for stakeholders?

Trust is actionable: Building trust where it matters most

“The people when rightly and fully trusted will return the trust.”—Abraham Lincoln

Our spring 2020 article on trust in the age of COVID-19 identified the questions stakeholders will need to ask themselves about trust across four dimensions—physical, emotional, digital, and financial—to walk in their stakeholders’ shoes, understand their worries, and understand how best to address their individual needs.

And, indeed, in our current disrupted environment, different stakeholders have different concerns related to trust along these dimensions: the physical safety of the worker contemplating going back to the office, the emotional safety of a family venturing to a resort for vacation, or the financial safety of a supplier dealing with uncertain lead times. While some stakeholders may be less concerned about the pandemic, others such as those caring for older family or immune-suppressed children will have no choice but to be vigilant. With so many varied contexts, it is challenging for leaders to engender trust. Building relationships across different stakeholder groups requires leaders to understand the dimensions (and nuances) relevant to each of them as individuals, and to address their specific concerns.

These four dimensions can act as a starting point to understand where stakeholders expect us to invest our time, attention, and energy for their benefit and security. To be sure, each group, whether customers, workers, suppliers, investors, regulators, society at large, or others, will prioritize their needs along the four dimensions of trust differently. Further, the way they prioritize each dimension will evolve with time; the physical dimension, for example, may give way to the emotional and financial as workers adjust to returning to the office and turn their attention to the need for transparency and employment stability. The ability to adjust and respond with agility to stakeholders’ needs will thus be crucial.

Driving real, actionable change

Agility isn’t just about operating models. It also describes how we need to respond to continuously evolving stakeholder needs. How are you sensing and monitoring the shifting needs of stakeholders along the four dimensions in order to address those needs?

Trust is human: Strengthening trust through connection and experience

“He who does not trust enough will not be trusted.”—Lao Tzu

When trust breaks down in an organization, it is often due to a failure on the part of leaders and organizations to understand and deliver on the signals that drive and enhance trust. We, as leaders, can demonstrate trustworthiness by being transparent with those whom we engage, reliable and capable in delivering on our promises, and human—demonstrating genuine care in the experiences they value most.18 As noted earlier, different stakeholders will prioritize different needs with respect to trust; the same is true for the experiences they desire from their interactions with us. As leaders, it is our task to ensure we create those touchpoints for our stakeholders and infuse those values throughout our organizations.

In May, Deloitte conducted a survey to understand what was important in signaling trust, and found that three-quarters of customers who highly trust a brand are likelier to take a leap of faith to try a new product or service from that brand; 79% of employees who highly trust their companies feel more motivated to work for them. In other words, trust drives experience—which drives behavior.19

Research led by neuroscientist Paul Zak indicates that trust and commitment “synergistically improve operational performance” as both trigger regions of the human brain to “motivate cooperation with others.”20 When the culture of the organization is suffused with trust, workers are more committed to driving success. Nicholas Epley and David Tannenbaum note how an organization’s culture can influence the behaviors of workers and how policies should “create contexts (within the organization) that promote ethical actions.”21 Leaders can take this one step further, assessing their impact in these areas by measuring, monitoring, and managing trust.22

Driving real, human change

Just as trust connects regions of an individual brain to drive cooperation, it also connects stakeholders across time and distance to do the same. Where do we need to intentionally create opportunities for more connections across stakeholders to enhance cooperation?

Trust is personal: A call for leaders

“Without trust, we cannot face the difficult challenges in our world today.”—United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres

In the words of British writer George Eliot, “Those who trust us educate us.”23 Truly walking alongside our stakeholders—understanding their concerns and their priorities—involves a willingness to listen, to learn, and to hear. At the outset, we proposed that building trust requires us, as leaders, to make conscious daily choices, and especially to act on those choices …

… Through mutual trust. When we as leaders trust our stakeholders, we enter an exchange that engenders opportunity: We prove our trustworthiness, and stakeholders empower us to take our organizations to new places and new innovations. In essence, mutual trust creates a followership that allows us to break new ground, to traverse the seismic changes taking place and emerge, thriving, on the other side of crisis.

… With vulnerability and honesty. Business leaders who are willing to acknowledge what they don’t know are more likely to engender trust with their stakeholders than those leaders who mistakenly believe their greatest source of influence is knowledge—or at least acting as though they know.24 A similar paradox exists for organizations responding to a one-time breach of trust. Stakeholders are likely to regain—and even strengthen—trust in the organization when leaders admit the mistake, are apologetic, and are transparent in how they move forward.25

… Where it matters most to your stakeholders. Intent connects the leader to their humanity and the importance of acting with transparency. But at the end of the day, intent is just a promise; leaders must be able to act on that promise, and do so competently, reliably, and capably. And they must be able to do so in the areas—whether physical, emotional, digital, or financial—that matter most to their stakeholders at that given time.

… By connecting as humans. Leaders who aspire to be trusted by their stakeholders take responsible actions that consider and, where possible, acknowledge the needs of each of those stakeholders. This requires an understanding of what is important to different stakeholders, and an ability to walk alongside them rather than an attempt to “walk in their shoes.”

If our efforts as leaders lead us back to where we were before the events of 2020, then we have failed. Our goal is not a new future, but a better future. Trust is the foundation for that better future, because it enables stakeholders to believe in the organization and its mission, its competence to succeed, and its intent to do good. Asking ourselves difficult questions as leaders will enable us to plot a path forward, to organize and prioritize our next steps around trust, and to operationalize it within our organization and across our stakeholders. Even when difficult choices must be made, trusted leaders and organizations have amassed the currency—and the courage—to make and stand behind those decisions with conviction and integrity.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more insights

-

Extended enterprise perspective Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the undisruptable CEO Article4 years ago

-

Confronting the COVID-19 crisis Podcast5 years ago

-

A case of acute disruption Article4 years ago

-

The kinetic leader: Boldly reinventing the enterprise Article4 years ago

-

Staying grounded in uncertain times Podcast4 years ago