An unbalanced age: Effects of youth unemployment on an aging society has been saved

An unbalanced age: Effects of youth unemployment on an aging society Issues by the Numbers, April 2015

30 April 2015

Patricia Buckley

Patricia Buckley

If young adults’ current high unemployment rate follows them across their work lives, funding retiree pensions and health care may be even more challenging than otherwise, as those with lessened prospects for income will be asked to support an ever-growing number of retirees.

View related infographic

Click hereWith youth unemployment still at high levels, many of today’s young people are getting off to a slow start in the job market, a situation that may well translate into lower lifetime earnings. At the other end of the age spectrum is a growing number of retirees who, under the current system, will be consuming an increasing proportion of the nation’s output. This twin tension is not unique to the United States; it is a hallmark of most advanced economies. As nations struggle to figure out how to adjust or pay for existing pension systems, they should also focus on policies to help improve the employment and earning potential of their younger workers.

Many of today’s young people are getting off to a slow start in the job market, a situation that may well translate into lower lifetime earnings.

The recession lingers for many young people . . .

The US labor market got off to a solid start in 2015 on the heels of robust growth in 2014. However, even as employment rises and the unemployment rate falls, not all participants in the economy are benefiting to the same degree. In particular, the youngest participants in the labor force generally continue to experience high levels of unemployment—much higher than might be expected if the historic differential with the older age groups had continued to hold. This is worrisome, as research shows that spells of unemployment early in one’s career can have a negative impact on lifetime earnings.

Similar to those in other age groups, many younger workers experienced a drop in labor force participation during the recession, with the reduction being very pronounced among the very youngest. Just prior to the recession, the labor force participation rate among those aged 16–19 (that is, the proportion of this age group working or looking for work) was 44 percent. During the recovery, the labor force participation rate for this group stabilized at 34 percent—a 10-percentage-point decline from its prior level. Among those aged 20–24, the decline was not as dramatic; the labor force participation rate in this group fell from 74.5 percent pre-recession to 71 percent post-recession, a decline on a par with that experienced by the labor force as a whole.1

One of the recession’s only positive aspects was that poor job prospects contributed to an increase in the number of young people choosing to continue their education rather than join the labor force. The percent of high school students that graduated reached an all-time high of 81 percent in the 2012–2013 school year, an increase from 79 percent in the 2010–2011 school year.2 Postsecondary enrollment also increased: Between 2007 and 2012, the proportion of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in a postsecondary institution increased from 38.8 percent to 41.0 percent, with the gain coming from increased enrollment in two-year institutions, which rose from 10.9 percent to 12.7 percent. (The percent of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in four-year institutions remained steady at 28 percent.3) This increased investment in education and training will likely benefit both the individuals receiving the education in the form of higher future earnings, and the US economy in the form of higher productivity—provided there are jobs available that need the skills acquired.

It is not unusual for unemployment rates to be higher for those under 25 than for those aged 25 and over. Rather, this has been the case since at least 1948, when the US government began to keep track. What is notable is that the difference in employment rates between younger and older individuals—which has historically been relatively constant—is growing, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. As shown in figure 1, over the course of the last two business cycles (from July 1990 through December 2007), unemployment rates for the two youngest cohorts maintained a stable relationship with the unemployment rates for those 25 and older: The unemployment rate for those aged 16–19 averaged 12.2 percentage points above the unemployment rate for those aged 25 and over, while unemployment rates among those aged 20–24 averaged 4.8 percentage points above those aged 25 and over. Since the beginning of the recession in December 2007, however, the employment rate differential between those aged 16–19 and those aged 25 and over has averaged 16.2 percentage points—four percentage points higher than before the recession. And although not as pronounced, the unemployment gap between those aged 20–24 and those aged 25 and over has also increased, to 6.6 percentage points in the current cycle.

What is notable is that the difference in employment rates between younger and older individuals—which has historically been relatively constant—is growing, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Given the 20- to 24-year-old cohort’s high labor force participation rate, their higher unemployment rate since 2007 has resulted in a significant increase in the number of unemployed between the ages of 20 and 24 (figure 2), which peaked at 2.6 million and is currently 1.6 million—a number still well above the average level in the prior two expansions. Further, it is only because of decreased labor force participation that the number of unemployed among those aged 16–19 is once again at the pre-recession level. It is key that those in that group who are currently not in the labor force because they are pursuing continued education will have job opportunities when they do enter the labor market.

This increase in the gap in unemployment rates between age cohorts does not bode well for the future earnings of affected members of the youngest age groups. New analysis by Deloitte shows that young people who experience a substantial period of unemployment early in their careers are on a lower income trajectory than those without longer breaks in employment. The latest National Longitudinal Survey of Youth conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics has followed a representative sample of American youths born between 1980 and 1984 since 1997 (when the youths were 12–16 years old). The most recently released data covers 2011–2012, when the participants were between the ages of 27 and 31. During the 14 years between 1997 and 2011, 68 percent of those in the sample experienced a period of unemployment of at least six weeks. A comparison of the current average earnings of those who had experienced a period of unemployment of six weeks or more with those who had not been unemployed, or who had been unemployed for a shorter period, shows that those experiencing a longer stint of unemployment have significantly lower average weekly earnings: $402 to $487—or a difference of just over $4,000 per year.4 If high levels of youth unemployment remain the norm, then average earnings for the population as a whole will be depressed as these younger cohorts age and more of the population is composed of those who have had substantial periods of unemployment early in their work lives.

. . . As clouds gather at the other end of the age spectrum

The employment and earning travails of those at the younger end of the workforce are cause for concern because many of the young people affected by the depth and length of the recession will likely be on a lower lifetime income trajectory than if they had come of age at an earlier time. However, the public policy concern becomes decidedly more acute when this fact is paired with the growing number of retirees that many of America’s younger workers will be helping to support.

With the Baby Boomers entering retirement, the 65-and-over age group is growing rapidly. In just the five years between 2015 and 2020, the number of people in this age group will increase by 17 percent—from 48 million to 56 million. By 2050, when those who are now 24 years old turn 65, the 65-and-over age group will total 87 million. In percentage terms, those aged 65 and over currently represent 14.8 percent of the US population. By 2055, that proportion will increase to 21.3 percent.5

At present, 90 percent of those 65 and older receive Social Security payments and qualify for Medicare.6 When the oldest members of the 16–24 age group turn 65 in 2055, these two programs are projected to consume 12.2 percent of GDP, up from the current 7.9 percent.7

Both Social Security and Medicare are financed through payroll taxes. Payroll taxes for each program are deposited into separate trust funds. When payroll taxes in a given year are not sufficient to pay all benefits due, the trustees draw from the balances accumulated in the trust funds in earlier years when the taxes coming in exceeded the benefit payments going out. Because of the faster growth in the number of retirees compared with the number of workers, payments being made from these funds have exceeded taxes paid in since 2010. Under current projections, the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund will not have sufficient funds to make full payments beginning in 2030, and the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance (OASDI) Trust Funds will be unable to make full payments beginning in 2033.8

Because of their funding mechanism, a standard way of considering the programs’ costs and income is as a percentage of taxable payroll. At present, the OASDI costs 14.0 percent of taxable payroll, which for this program includes earnings up to $117,000. Because of this cap, the tax burden of the OASDI falls more heavily on lower-income earners, as income above $117,000 is not subject to this tax. However, OASDI payroll taxes and interest income only bring in an amount equal to 12.7 percent of payroll. With costs higher than income, the difference is made up by using the accumulated assets in the OASDI Trust Funds. By 2055, OASDI’s costs will have risen to an amount equal to 17.0 percent of payroll, while its income will have risen to only 13.2 percent of payroll. Meanwhile, while Medicare costs and income are currently virtually identical at 3.4 percent and 3.3 percent, respectively, its costs will equal 5.2 percent of payroll by 2055, while its expected income will only be 3.9 percent.9

Taken together, these two programs are projected to cost 22.2 percent of taxable payroll when the oldest of the current 16- to 24-year-old cohort begins to retire, up from 17.4 percent currently. However, the programs’ income will rise only slightly from the current 15.0 percent of taxable income, to 17.1 percent. This means that there will likely still be a sizable amount to make up, equal to just over 5 percent of taxable payroll. If the challenges are not addressed, the trust funds will be depleted in 15 years, causing the need for payroll taxes to rise or benefits to be reduced.

If the challenges are not addressed, the trust funds will be depleted in 15 years, causing the need for payroll taxes to rise or benefits to be reduced.

A transatlantic conundrum

The United States is not the only country facing the confluence of these two trends. High youth unemployment amid an aging population is a transatlantic phenomenon, affecting not only the United States but also Canada and most of the countries in the European Union. And as problematic as the situation is in the United States, the challenge may be even more immediate and severe in other countries.

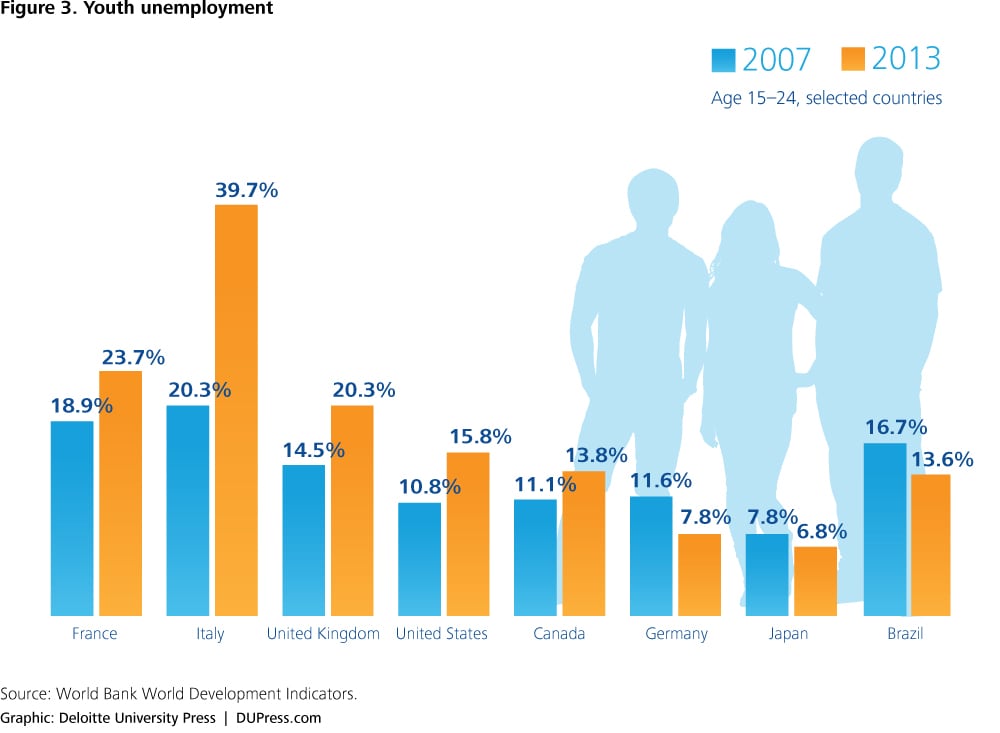

The “great recession” impacted individual countries’ employment situation to different degrees, and the relative speed of recovery has also been highly variable. Of the countries shown in figure 3, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, the United States, and Canada all had overall unemployment rates between 1.0 to 2.5 percent higher in 2013 than in 2007. However, when one considers youth unemployment rates, the difference is substantially greater: Excluding Italy (which has a 19-percentage-point differential), youth unemployment in this set of countries is between 2.7 and 6.0 percentage points higher than its pre-recession level. Most of the other countries in Europe also follow this pattern. Germany and Japan stand alone among the larger industrialized nations in having had both their overall unemployment and youth unemployment rates return to or fall below their pre-recession rates. Brazil is included in figure 3 to illustrate the success that some emerging markets have had in bringing down not only overall unemployment, which fell from 8.1 percent in 2007 to 5.9 percent in 2013, but also youth unemployment.

When looking at the other end of the age spectrum, the next 35 years will see a sharp rise in the number of retirees that each of the economies in figure 3 will need to support, as shown in figure 4. Even though youth unemployment is not a particular problem in Germany and Japan, their populations are aging far more rapidly than those of other countries. Both countries currently have 32 retirees for every 100 people of working age (that is, those aged 15 to 64); by 2050, that proportion will rise to 53 to 100 in Germany and 82 to 100 in Japan. The countries with high youth unemployment shown in figure 3 above will also have much larger retiree populations to support in 2050, although the rise in the proportion of retirees to working-age individuals will not be as dramatic as in Germany and Japan.

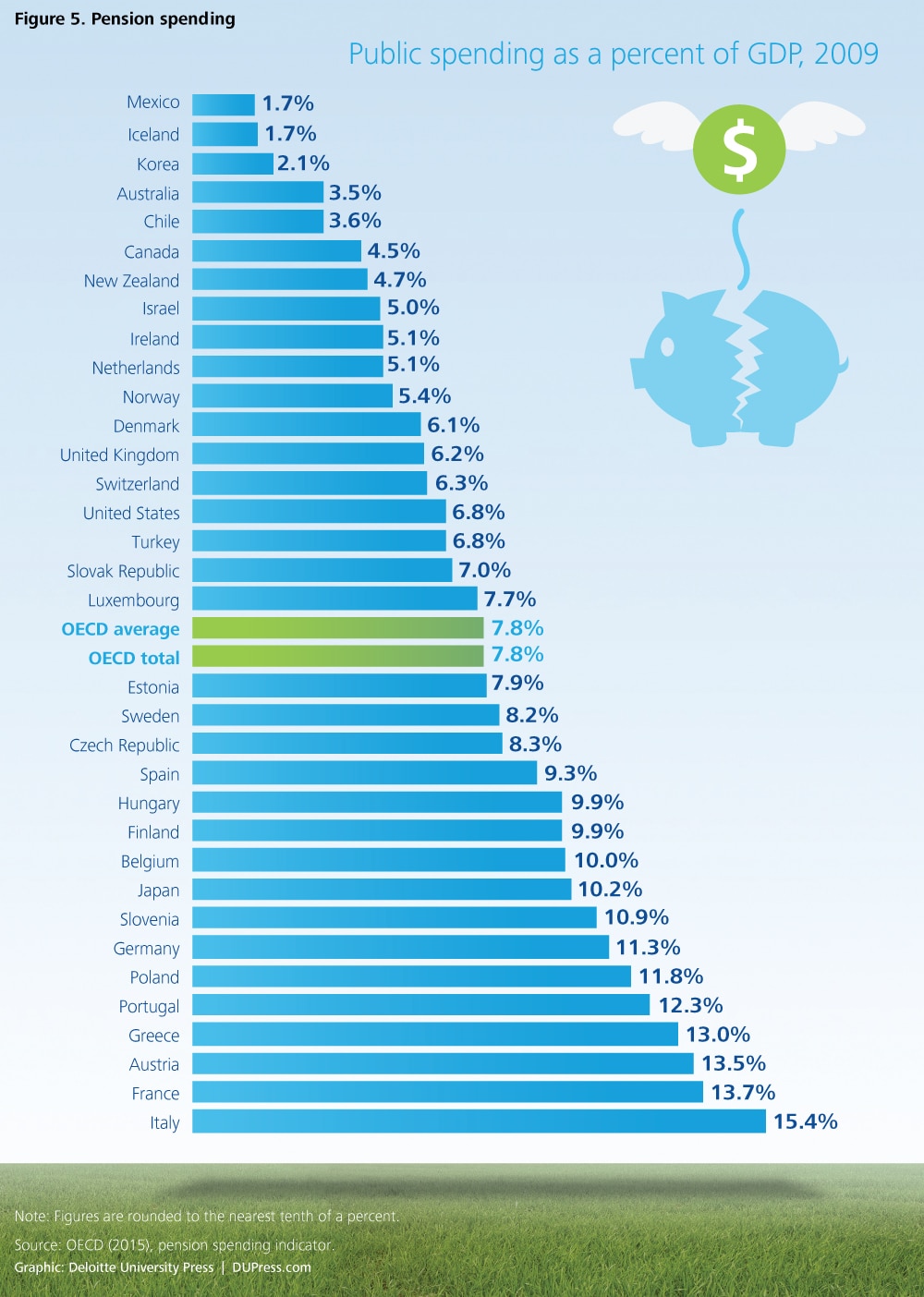

As shown in figure 5, the 34 countries that comprise the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) pay varying amounts to support their retiree populations, ranging from around 2 percent of GDP in Mexico, Iceland, and Korea to more than 13 percent in Greece, Austria, France, and Italy. The United States comes in just below the OECD average. Given the substantial rise in the number of retirees these economies will need to support in coming years, the cost of pensions (public and private), which is already very high in some countries, will likely increase even more.

A question of generational equity

The severity and the duration of the most recent recession fundamentally reshaped the lives of many across the globe. In the United States, the number of unemployed surpassed 15 million,10 home foreclosures skyrocketed, and significant wealth accumulated through home equity and stocks was lost. Many younger members of the labor market were hit particularly hard, and even as the recovery picks up steam, their job prospects often remain muted. If the high rate of unemployment among young adults continues to follow them across their work lives, permanently depressing their earnings, addressing the funding conundrum of retiree pension and health care will be even more difficult than otherwise. In such a case, those with lessened prospects for income will be asked to support an ever-growing number of retirees—many of whom may have had opportunities for success not as widely available to the current cohort of young workers. This raises a question of generational equity: How much is fair to ask from today’s younger people to help support their elders? Now is the time to consider strategies to cope with this new world situation, before today’s young people become additions to the growing population of retirees.

This raises a question of generational equity: How much is fair to ask from today’s younger people to help support their elders? Now is the time to consider strategies to cope with this new world situation, before today’s young people become additions to the growing population of retirees.