Millennials: The overqualified workforce Economics Spotlight, January 2019

6 minute read

31 January 2019

Millennials may be the most well-educated of the generations so far, but they also seem to be overqualified for the jobs they are doing.

In 2017, the Urban Institute reported that one in every four Americans with bachelor’s degrees is overqualified for their job.1 According to a survey by Business Insider, that number is even higher (about 35 percent) for college-educated millennials.2 We looked more closely at the millennial experience using a unique data set (see sidebar, “The NLSY data set”) to find out if this was true—and what it means, in practice.

Learn more

Read the most recent US Economic Forecast

Explore the Economics Spotlight collection

Subscribe to receive more economics content

Are college-educated individuals “settling” for jobs that are “beneath” them?

Millennials are considered to be the most educated generation. Compared to baby boomers, 4 percent more male millennials and 13 percent more female millennials have completed a bachelor’s degree.3 The NLSY data supports this finding—by 2015, 36 percent of the NLSY cohort had completed a four-year college program (see figure 1), validating the Business Insider findings.

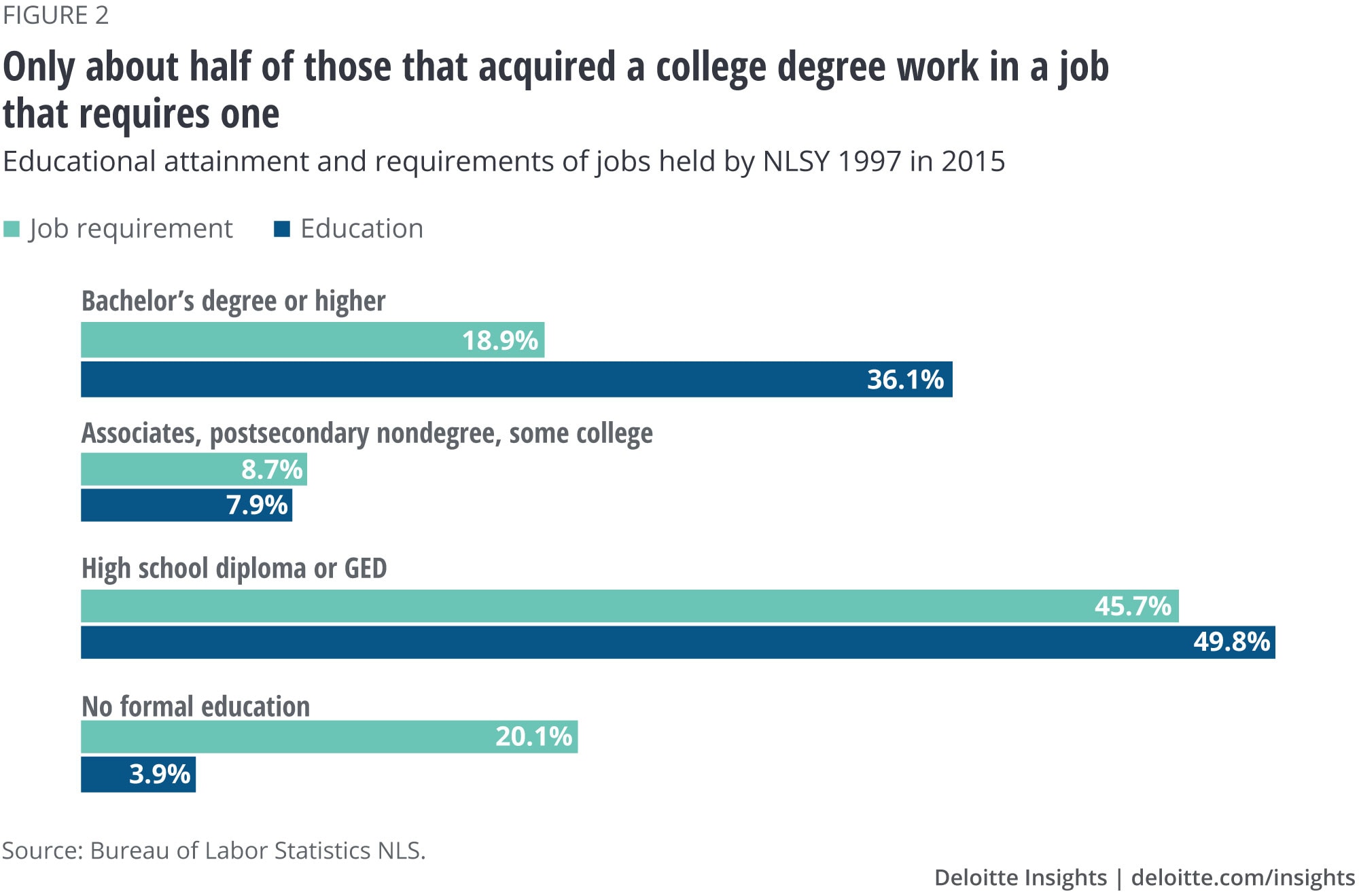

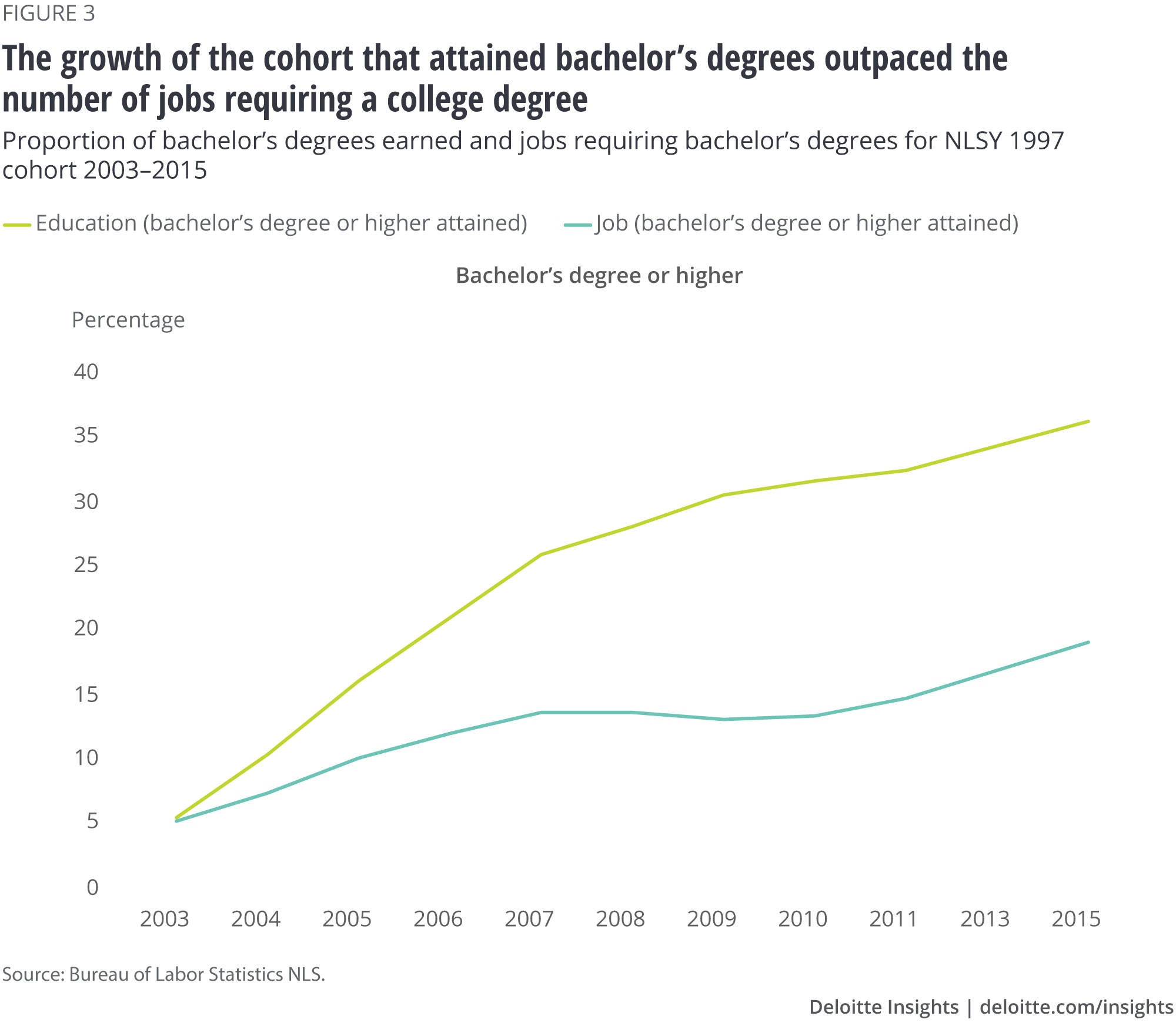

However, although educational attainment is growing, the number of jobs that require higher education is not growing as rapidly. Of the 36 percent of the NLSY cohort that obtained a college degree by 2015, only 19 percent worked in a job that required a bachelor’s degree or higher (see figure 2). Meanwhile, even though nearly half the cohort held some type of degree, 66 percent of the jobs held by this group required no more than a high school diploma or GED. Figure 3 shows that the share of jobs held by the cohort that required a bachelor’s degree grew over this period—but more slowly than the share of the cohort that held bachelor’s degrees.

There are several reasons why so many people might be willing to hold jobs that don’t require their highest level of education. First, BLS notes that educational requirements for each job are assigned based on the minimum requirement of the job and not the worker. It’s certainly true that not everybody wants to match their degree to a job. It is possible that a worker with a degree may be prospering in a satisfying job with no degree requirement. Similarly, some individuals stay with an employer, either while obtaining their degree, or while moving up the ranks within that company. This may lead them to keep jobs that don’t require a degree, while the degree still provides value (in terms of higher productivity and pay).

Another possibility, however, is that job options do not match educational attainment. There just may not be enough jobs that require, and make use of, the additional education people have obtained. This would leave them with no choice but to take jobs that don’t justify their educational investment. Many college graduates, particularly those with massive student loan debt, may “lower the bar” just so they have a paycheck—even if they are overqualified. A look at some types of jobs filled by overeducated NLSY respondents suggests that this is an important factor in the observed overqualification.

As of 2015, a reported 17 percent of waiters and waitresses and 33 percent of retail salespeople in the NLSY cohort held a bachelor’s degree or higher (see table 1). Both are examples of occupations that classify as requiring no formal educational credentials and are unlikely to provide long-term satisfaction or occupation advancement to those with advanced degrees. Meanwhile, many jobs requiring a high school diploma show significant penetration by holders of college degrees. For example, 100 percent of eligibility interviewers for government programs in the cohort have BAs or higher, although BLS classifies the job as not requiring a degree. And 32 percent of surveying and mapping technicians—another job classified as not requiring a degree—have master’s degrees.

Overqualification rates are substantial even for occupations requiring bachelor’s degrees. In 2015, 100 percent of actuaries, 58 percent of personal financial advisors, 47 percent of financial analysts, and 42 percent of mechanical engineers in this cohort held master’s degrees in those occupations, all of which (according to BLS) require no more than a bachelor’s degree. This is an alarming reality for college-educated millennials, who may find themselves competing with others who have more advanced degrees. An “inadequate” candidate is left to do one of two things: pursue a higher degree themselves or find another occupation.

How did this trend begin?

For older millennials, such as the NLSY cohort, the recession likely played a role in this college surplus. The Pew Research Center found that unstable job markets encouraged young adults to go back to school or pursue more advanced degrees, effectively prolonging their college career.4 Although most of this cohort finished their degrees by 2007, the share of degrees continued to grow after this date (see table 1). This is regardless of the fact that college has continued to become relatively more expensive—from 2007 to 2015, the Consumer Price Index for college tuition has grown at an annual rate of 4.8 percent, more than twice the overall annual CPI rate of 1.7 percent during the same period.5 The slow recovery that followed the recession also encouraged the cohort to continue obtaining degrees for some time, resulting in a continuous influx of highly educated new workers.

The value of a degree

We previously studied the same NLSY cohort and found that occupation type matters more for pay than a degree. 6 In fact, in the NLSY cohort, there is still a 35 percent chance of an individual earning a degree but taking a job that does not require one. Our studies raise some significant questions about the value of a generic college degree. We have to wonder whether the push to pursue a degree, or an advanced degree, is always good advice. Potential students might want to consider this before taking out those loans that are the mark of the over-educated millennial.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more economics content

-

All in a day’s work—and sleep and play: How Americans spend their 24 hours Article6 years ago

-

Where’s the labor shortage? Article7 years ago

-

How is the government workforce similar to the private sector? Article8 years ago

-

No college, no problem? Article7 years ago