All in a day’s work—and sleep and play: How Americans spend their 24 hours Issues by the Numbers, November 2018

20 November 2018

How do Americans spend their 24 hours each day? Data from the American Time Use Survey illuminates what Americans tend to do with their time, offering valuable insights to policymakers, economists, and businesses.

How much sleep does the average American get each day? How much time do Americans typically spend at work and at play—and when at play, what do they do? Intrusive as these questions might seem, it’s not just nosiness that makes people ask them. Knowing what people do with their time can offer valuable insights to policymakers seeking to improve public health, economists trying to understand labor market trends, and businesses working to better attract and serve customers. Consumer goods and services companies, in particular, may benefit from understanding how Americans tend to allocate their time each day, as this can inform their sales and advertising strategies and help them identify macro marketplace trends.1

Fortunately for those of us eager to know, the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) can give us a window into Americans’ typical daily activities.2 The survey, inaugurated in 2003, tracks various activities—including work, travel, leisure, and sleep—among a representative sample of Americans each year.

Learn More

View the related infographic

Subscribe to receive economics content from Deloitte Insights

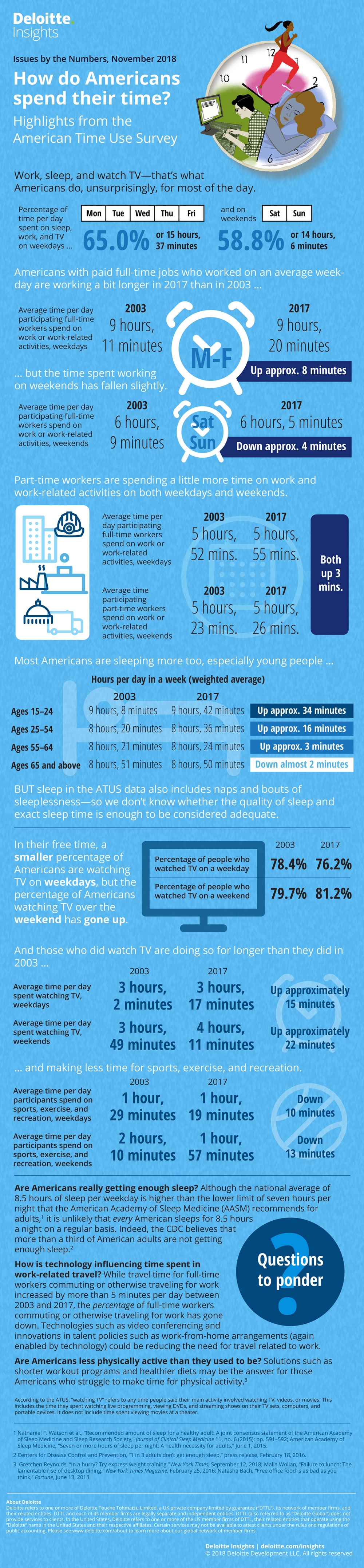

So how do Americans spend their daily 24 hours? Broadly speaking, and unsurprisingly, they spend the bulk of each weekday doing one of three things: working, sleeping, or watching TV.3 In fact, taken together, the proportion of each weekday consumed by these three activities has gone up between 2003 and 2017 (figure 1).

Of course, one doesn’t need a research study to figure out that Americans spend a lot of time sleeping, working, and watching TV. The beauty of the ATUS data, however, is in its details. When one drills down into the different components of each major activity, studying trends over time, and comparing the findings across age groups, the data reveals several interesting trends.

Americans with jobs are working more

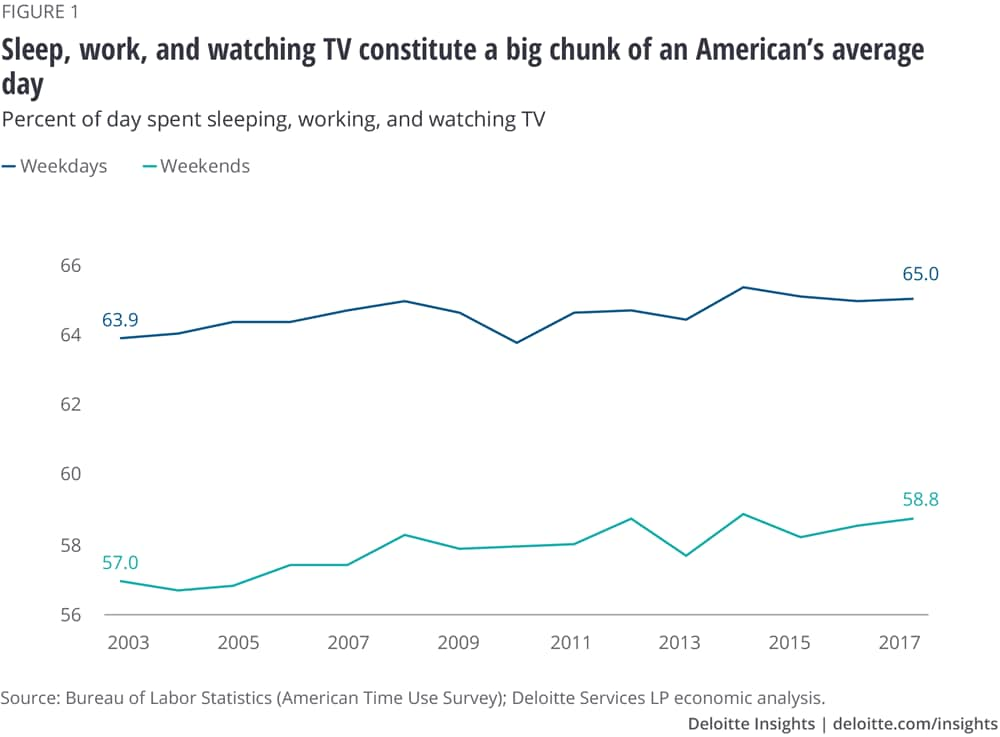

Americans with jobs—both part-time and full-time—are spending more time at work and on work-related activities4 today than they did in 2003. In 2017, Americans who were engaged in full-time5 paid work put in a little more than 9.3 hours of work and work-related activities on an average weekday,6 about 8.4 minutes more per weekday than in 2003. Part-time workers, too, spent more time working on an average weekday in 2017 than in 2003, although this amount has fluctuated greatly from year to year.

Interestingly, among full-time working Americans, the average time spent on work and work-related activities on weekends decreased sharply in 2009—by about 32 minutes per day (figure 2). Although this has trended up since then, full-time workers are still putting in less work per day on weekends than they did in 2003.

Full-time workers who commute or otherwise travel for work spent an average of 52.2 minutes each weekday doing so in 2017; this is 5.4 minutes per day more than in 2016, although this statistic did not change much between 2003 and 2016. Weekend work-related travel went up by just 36 seconds per day between 2003 and 2017. More interestingly, the percentage of full-time workers engaged in travel related to work on weekdays decreased from 80.9 percent in 2003 to 77.5 percent in 2017. This finding seems surprising, considering that the percentage of full-time workers who actually worked on an average weekday went up between 2003 and 2017 by a full percentage point. It is likely that technologies such as video conferencing and innovations in talent policies such as work-from-home arrangements (again enabled by technology) are reducing the need for travel related to work.7

Not surprisingly, people who were classified as “not employed” spent a little less than an hour per week on paid work and work-related activities. On the other hand, they slept longer (+6.3 hours), watched more TV (+12.6 hours), and spent more time on educational activities (+5.6 hours) per week than Americans who were employed full-time. It is worth noting that most of the people who the ATUS classifies as “not employed” are probably either young people (such as those aged 15–24 years) or older people (aged 65 or more). Although the ATUS data does not support a split of this variable by age, other evidence exists that suggests that the younger people in this group likely engaged more in educational activities than the older ones,8 who may be spending more time in front of the TV.

A few more minutes of snooze time

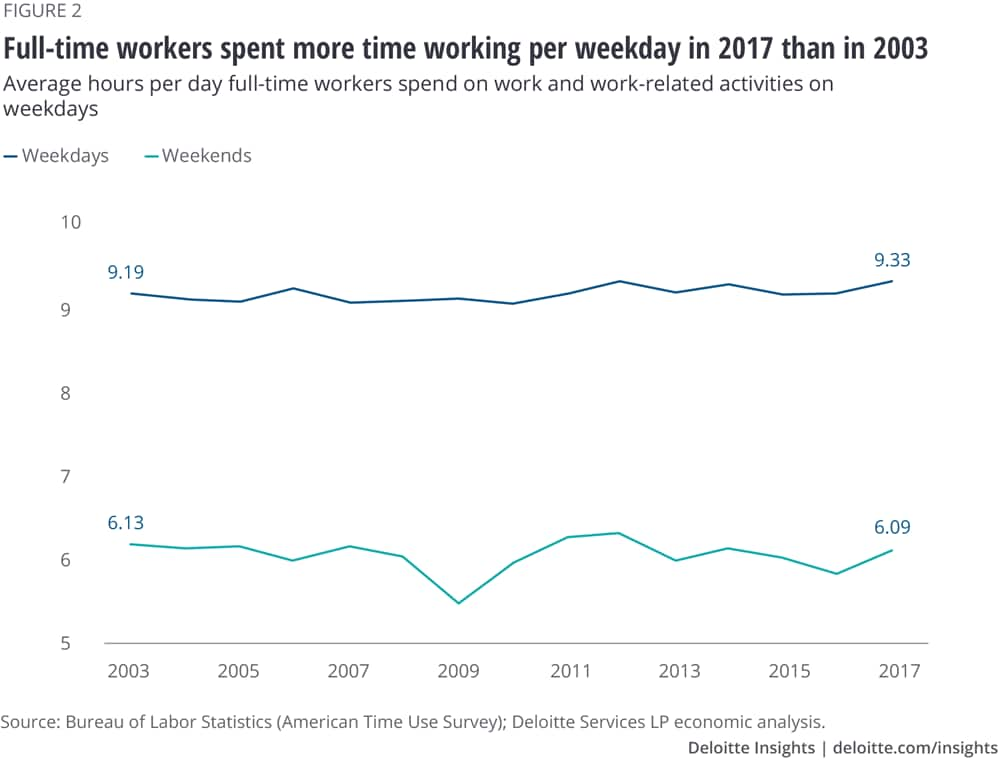

The average American slept for 8.5 hours on a typical weekday in 2017. That’s up from 8.3 hours per typical weekday in 2003. On weekends, too, Americans are sleeping more than they did in 2003 (figure 3). As a result, average weekly sleep time has gone up by 100 minutes.

Who’s getting all this extra sleep? On a minutes-per-day basis, it’s mostly younger people: 15–24-year-olds got 38 minutes more sleep per weekday in 2017 compared to 2003, and 25–54-year-olds got 16.8 minutes more sleep per weekday. Older people, on the other hand, barely increased their sleep time between 2003 and 2017. Fifty-five–64-year-olds slept 1.8 minutes more per weekday in 2017 than in 2003, and those aged 65 or more only increased their sleep time by just over half a minute. However, because the percentage of older people in the total US population has been increasing over the years,9 the two older cohorts actually contributed more than their younger counterparts to the overall national increase in weekday sleep time—even though they aren’t sleeping many minutes more than in 2003.

With Americans sleeping more, is sleep deprivation, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) described as a “public health epidemic” in 2014, still a concern?10 It’s hard to tell from the ATUS data, but it seems probable that a large share of Americans may still not be getting adequate sleep, thereby continuing to risk poorer health and decreased productivity at work.11 Three factors make this likely. First, the ATUS data on sleeping does not reflect the true extent of sleep time, as it also includes naps and spells of sleeplessness.12 Moreover, although the national average of 8.5 hours of sleep per weekday is higher than the lower limit of seven hours per night that the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recommends for adults,13 it is unlikely that every American sleeps for 8.5 hours a night on a regular basis. Indeed, the CDC believes that more than a third of American adults are not getting enough sleep.14 For young adults and individuals recovering from sleeplessness or illness, even 8.5 hours per day may not be enough; experts recommend more than nine hours of sleep for such individuals.15 Finally, full-time workers may be worse off than the average of 8.5 hours per weekday suggests, as the ATUS data reveals that those who were employed full-time slept 34 minutes less than the national average on weekdays in 2017.

More time in front of the TV

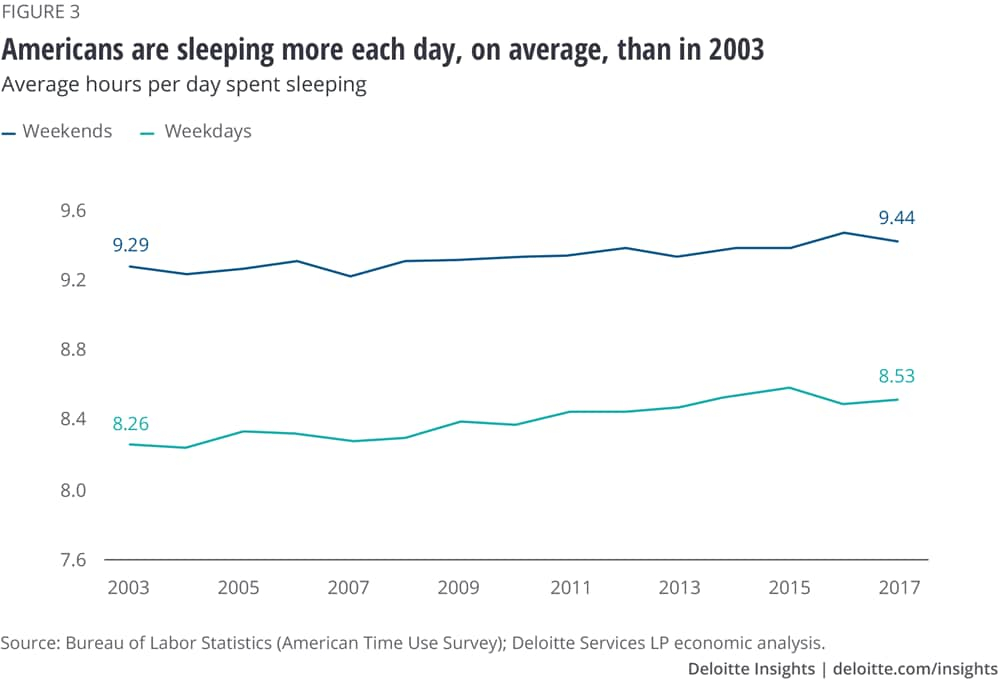

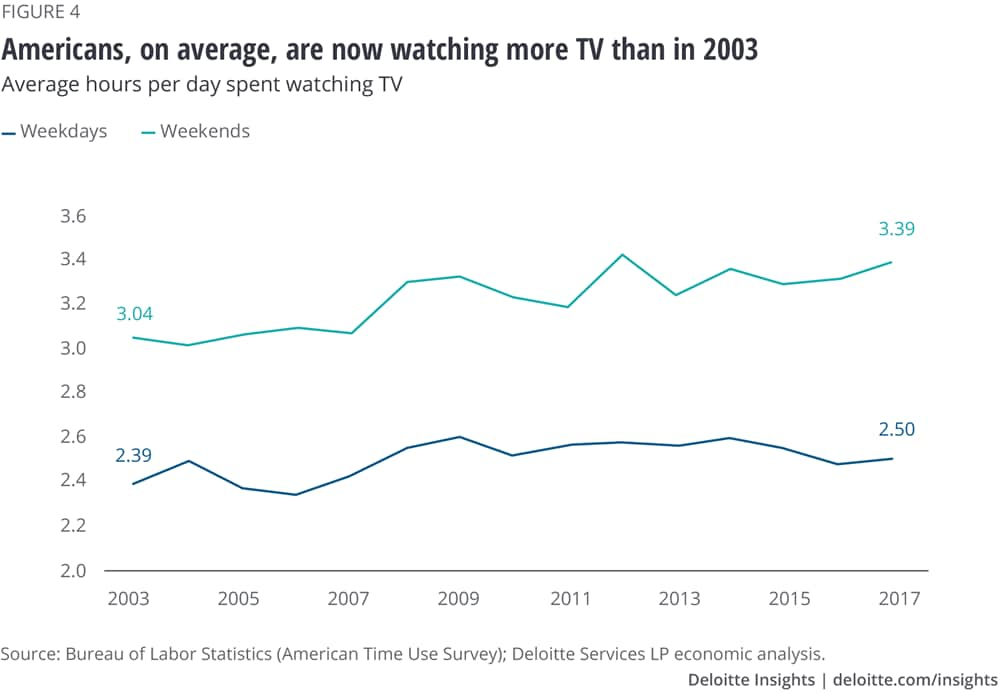

The time Americans spend on leisure and sports16 on an average day has been on a gentle upward trend since 2003, with this trend more distinct for weekends than for weekdays. However, it’s unclear whether this is good news from a health perspective. Why? Because more than half of the time recorded in the “leisure and sports” category is spent watching TV—an activity that has consumed more and more time over the years (figure 4).17

That Americans, on average, are watching more TV doesn’t necessarily mean that more people are doing so now than in 2003. In fact, the percentage of people who watched any TV at all on an average weekday fell from 78.4 percent in 2003 to 76.2 percent in 2017. That said, the percentage of people who watched any TV on weekends went up from 79.7 percent to 81.2 percent during the same period. What really explains the rise in average daily TV-watching time is that those who watched TV are spending more time per day doing so, whether on a weekday or over the weekend.

Older Americans are more likely to indulge in TV than younger ones; the proportion of younger individuals who watched TV declined on weekdays and was relatively flat over weekends from 2003 to 2017. This may not be good news for older Americans, especially 55–64-year-old workers: After spending longer hours at work on weekdays, getting some exercise would seem better for their health than more screen time.18

Less sports, exercise, and recreation

The time Americans spend on sports, exercise, and recreation—another component of ATUS’s “leisure and sports” category—has remained relatively flat between 2003 and 2017. Two opposing trends, one offsetting the other, are at work here. On the one hand, a greater proportion of people are participating in some form of sports, exercise, and recreation on both weekdays and weekends. To cut the data by age, the proportion of 15–24-year-olds, 25–54-year-olds, and those aged 65+ years engaging in these activities has increased—albeit to different degrees—from 2003 to 2017 (figure 5). However, across all age groups, those who participated in such activities spent less time on them in 2017 than in 2003—except for the 65+ group, who averaged a 7.2 minutes more of sports, exercise, and recreation on a typical weekday.

One worrisome trend is that the proportion of 55–64-year-olds participating in sports, exercise, and recreation on a typical weekday dropped from 2003 to 2017. Besides, those in this age group who engage in such activities are spending 13.8 minutes less on them in 2017 than in 2003. Again, this is a trend that may not be conducive to this age group’s overall health and well-being.

Caring for household members: Time up, participation down

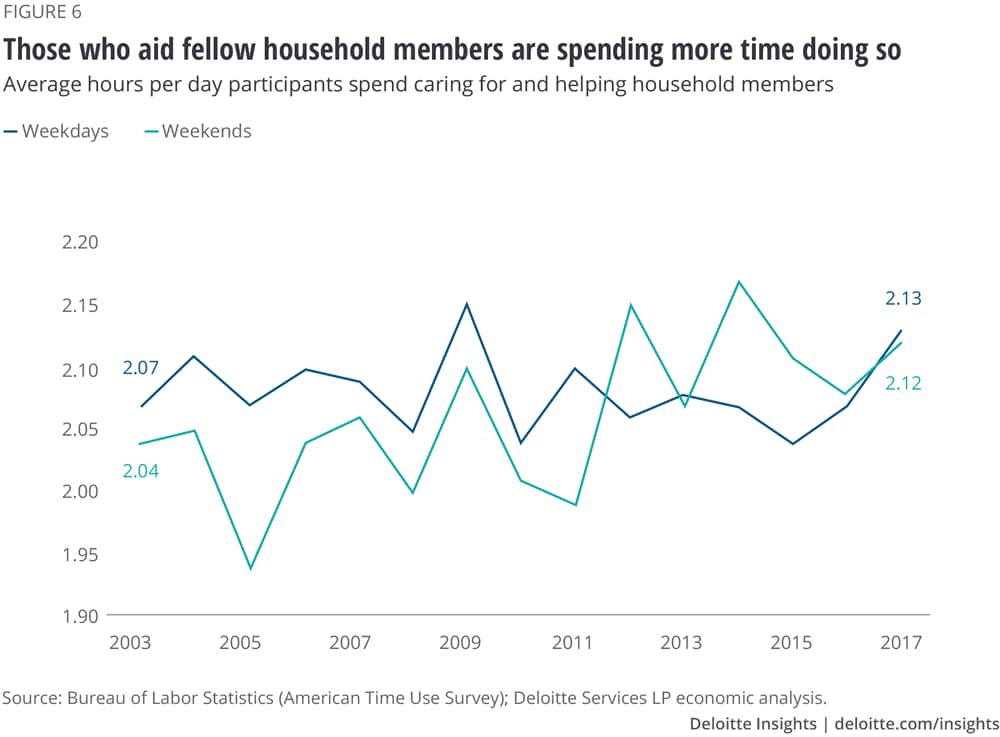

The proportion of Americans who care for and help household members is decreasing—down by about 2.9 percentage points per day for weekdays and 1.1 percentage points for weekends from 2003 to 2017, although the proportion of people caring for adults within the household has gone up slightly since 2011. The proportion of those who care for children is also on a broad decline. Among those who do care for and help household members, however, the time they spend on these activities has increased—both on weekdays and weekends (figure 6).

Three factors may be contributing to these trends. First, the falling birthrate—12.2 births per 1,000 people in 2016 compared to 14.1 in 200319—means that fewer households are having children and, hence, participating in child care. Second, the concepts of working from home and work/life balance are increasing in vogue; this may be helping working people to spend more time with their family. Finally, as America ages, the need for elder care is going up.

Food, glorious food

In 2017, 75.6 percent of Americans performed some kind of household activity, such as housework, food preparation and cleanup, and lawn and garden care, on a typical weekday. This proportion is slightly higher than it was in 2003. Weekend participation in household activities has also increased since 2003. The amount of time these participants spend on household activities every day, however, has remained mostly constant.

At a more granular level, the trend for food preparation and cleanup is notable. A greater proportion of Americans engaged in food preparation and cleanup in 2017 than in 2003 (figure 7). Although they spent roughly the same amount of time on this activity in 2017 than in 2013, the growth in the percentage of people who engage in food preparation and cleanup has pushed up the average time spent on this activity by about 27 minutes per week.

Does the increase in the average time they spend preparing food and cleaning up afterward mean that more Americans are eating at home and spending less on food outside? Not really. According to the Survey of Consumer Expenditure (SCE), average consumer expenditures for food at home grew more slowly between 2003 and 2017 (2.4 percent per year, on average) than spending on food away from home (3.0 percent).20 That said, much of the steep rise in spending on food away from home happened after 2013—a period where the increase in time spent (on average) on food preparation and cleanup has been more muted. It is likely that, with the economy strengthening since 2013,21 people are now more willing to spend money to eat out than they were just after the Great Recession.

Somewhat counterintuitively, the proportion of Americans traveling to eat and drink shows a slight downward trend, which likely reflects the rising use of food delivery services.22 A similar trend emerges for travel related to purchases of goods and services (figure 8). Technology is likely a key factor behind both of these trends: With food delivery services readily available through the internet, and with e-commerce’s share of total retail sales continuing to grow,23 many people may find it more convenient to have food and other purchases delivered to their doorstep than to venture out to buy them.24

What can we do with this data?

The ATUS data offers insights that can be useful to businesses and policymakers. They may, for example, find it worth considering ways to increase well-being and work/life balance among American workers, given that they are putting in more time at work now than they used to. If technology-enabled concepts such as remote work are proving successful—for both workers’ well-being and their productivity—they could be more broadly adopted. Workers commuting long hours and those with a family to care for back home may relish such moves.

The concept of well-being is closely related to sleep. While Americans are sleeping more on average, according to the ATUS data, it is unclear whether they are doing so regularly. More research may be needed in this area to inform efforts among businesses, policymakers, health professionals, and individuals themselves to promote more and better sleep.

Another area of concern is the decline in time spent on sports, exercise, and recreation since 2003, despite the rise in the percentage of people engaging in such activities. Solutions such as shorter workout programs and healthier diets may be the answer for those Americans who struggle to make time for physical activity.25

Knowing how people spend their time can help businesses understand their target customers and push appropriate products and services out through the right platforms. (Data on secondary activities such as using social media, watching live streaming, or talking on the phone while traveling—activities that the ATUS does not track—would help even more.)26 Businesses can also turn to time-use data to identify changes in consumer preferences. For example, with fewer people attending sports and recreation events than in the past, the sports industry is being forced to innovate to induce fans to come back to the stadium rather than watch the events on TV.27

To understand the way people spend their time is an important part of any solution to improve lives or to create or widen markets. In the process, if Americans can save a few extra minutes in a day or an odd hour in a week for themselves, friends, or family, they will likely be happier. After all, who doesn’t value time?

Explore Issues by the Numbers

-

Are we headed for a poorer United States? Article6 years ago

-

No college, no problem? Article7 years ago

-

Income inequality in the United States Article7 years ago

-

The aging water infrastructure Article8 years ago

-

A new understanding of Millennials Article9 years ago