Wealth inequality: The reasons behind the growing gap Economics Spotlight, June 2018

26 June 2018

The net worth gap between the top 10 percent of US households and the bottom 25 percent continues to widen. A review of the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances provides insight as to why this gap is expanding.

Wealth inequality in the United States may be one of the more troubling features of the current US economy. In 2016, for example, the real median net worth of the top 10 percent of households (by net worth) was about 24,000 times the corresponding value for the bottom 25 percent.1 If you find that a bit tough to digest, here likely is a bigger surprise: Wealth inequality has gone up over time; back in 1992, for example, the above-mentioned ratio was much lower (just 1,300). What explains this chasm in wealth among households? And why is the gap widening? To find out, we dip into the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), which provides some of the leading information on the wealth of US households—who owns the wealth and how they invest it.

The data from the SCF throws up multiple insights. First, the wealthiest households in the country are also the highest income earners and the gap in income between them and poorer households has gone up over the years. Second, because the wealthiest households have more assets than poorer ones, they have higher investment incomes. Third, asset portfolios of the wealthy include more of stocks and real estate—riskier than the transaction accounts that hold much of the wealth of poorer households, but, with higher returns over time. As a result, asset accumulation for the wealthiest has increased at a faster pace than that for those at the bottom of the wealth ladder.

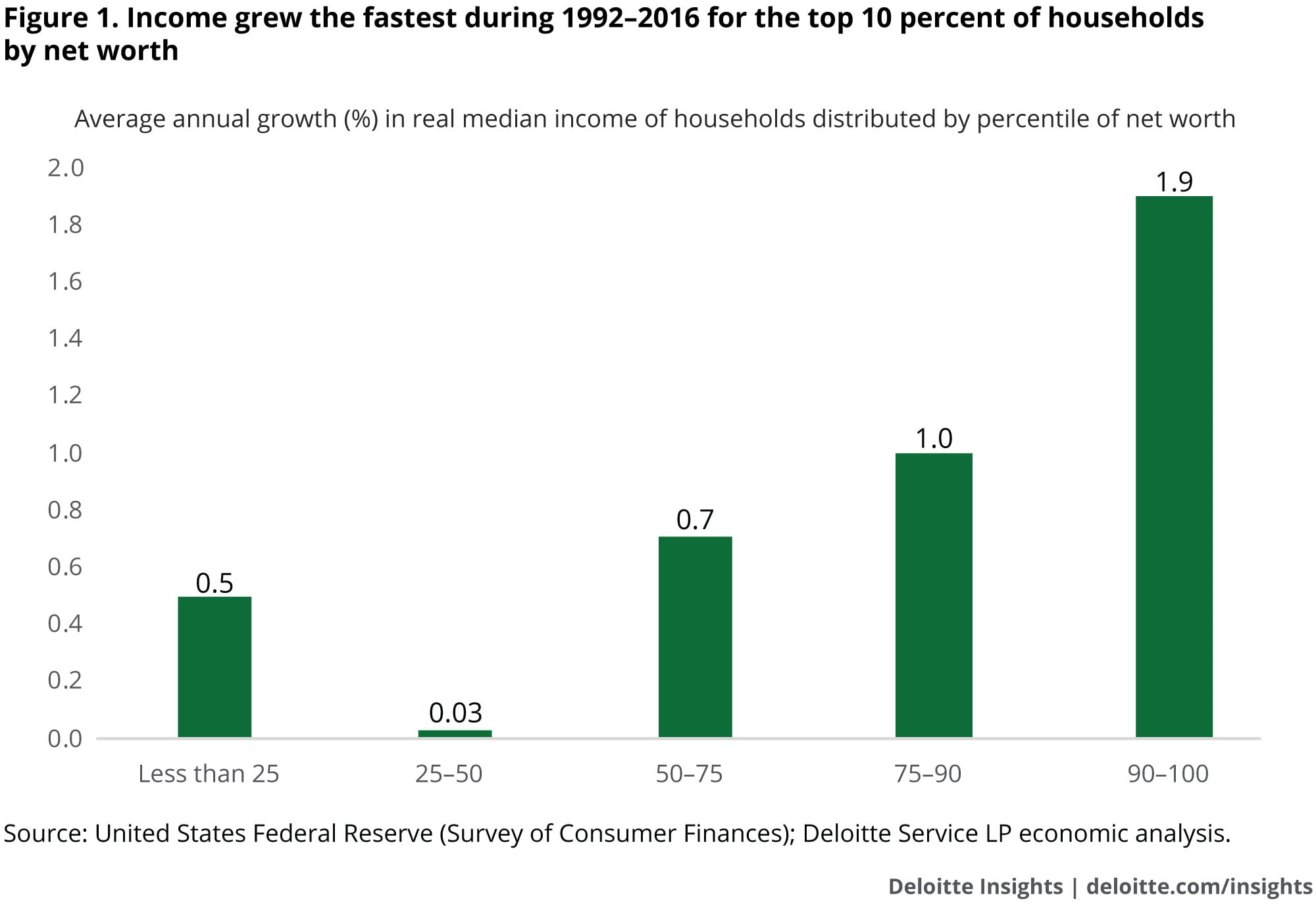

If a household earns more, it can add more to its wealth

The wealthiest households not only earn more, but, their incomes have been growing faster than others. In 2016, real median income for the top 10 percent of households by net worth was $215,700, about 8.5 times the corresponding figure for the bottom 25 percent of households. Back in 1992, the ratio was lower (6.1). Between 1992 and 2016, real median income for the wealthiest 10 percent of households grew at an average annual rate of 1.9 percent; the corresponding rise for households at the bottom 25 percent was 0.5 percent. Figure 1 shows how incomes have been rising faster for wealthier households.

More assets it owns, the wealthier a household can get

In 2016, the real median value of asset holdings of the wealthiest 10 percent of households who held any asset—financial or nonfinancial—was close to $2.6 million. This was 361 times the value of holdings for households in the bottom 25 percent (see figure 2). And this ratio was much higher than what it was in 1992 (192). Figure 2 also shows that the real median value of assets between 1992 and 2016 has increased the most for the wealthiest 10 percent of households. The story does not change much if we compare households against their holdings of financial and nonfinancial assets. In 2016, the wealthiest 10 percent households who held any financial asset had financial assets with a real median value of about $1.3 million; for the top-wealth households who held nonfinancial assets, the real median value of such assets was $1.2 million. In contrast, households at the bottom 25 percent of net worth, which had financial assets, owned just $1,000; and for those who owned nonfinancial assets, the median value was just $9,200.

Riskier assets imply higher returns and, hence, more wealth

An analysis of the asset portfolios of households reveals that the wealthiest households are more likely to own stocks—both direct and indirect holdings—and own relatively more stocks. Table 1 shows that of the top 10 percent of households by net worth in 2016, 50.6 percent of them held stocks directly compared to only 2.1 percent for households in the bottom 25 percent. And of those households that held stocks directly, the real median value of such holdings for the top 10 percent was $200,000, compared to just $1,700 for the bottom 25 percent.

Table 1 also reveals that the wealthiest households have relatively larger indirect holdings of stocks (such as retirement accounts, pooled investment funds, and other managed assets). The same holds true for holdings in real estate, including primary residence, other residential property, and equity in nonresidential property. And as figure 3 highlights, while the median value of key risky holdings—equity and real estate-related—has gone up over the years for the top 10 percent of households by net worth, the median value of holdings of similar assets (except for primary residence) of the bottom 25 percent of households have not made much headway.

Households at the bottom 25 percent are more likely to own assets that do not yield much or any returns, such as transaction accounts. About 95.2 percent of such households have transaction accounts, almost close to the 100 percent figure for the top 10 percent of households by net worth. Yet, even here, there is a vast difference in the median value of such accounts between the top 10 percent and the bottom 25 percent (see table 1).

The trend is unlikely to change any time soon

Not only are their incomes rising by less than the wealthiest, poorer households appear less likely to save as well. The latter, for example, are using up more of their income to repay debt. In 2016, the leverage ratio (ratio of liabilities to assets) for the bottom 25 percent of households by net worth was a staggering 141.6 percent (but just 4.8 percent for the top 10 percent) and these households spent about 13.1 percent of their family income in repaying debt (just 6.7 percent for the top 10 percent). Unless they are using this debt to acquire assets such as a home, they are not likely to be able to accumulate wealth under these conditions. This suggests that poorer households may be substantially handicapped in their ability to acquire assets.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.