From cargo containers to bytes: Unpacking US services trade Economics Spotlight, July 2018

27 July 2018

The changing nature of trade increasingly involves “unpacking” bytes rather than unpacking cargo containers as services such as consulting and exchange of intellectual property flow across national borders digitally. The US economy appears well-positioned to benefit.

The United States has a sizable and growing trade deficit—a condition that has persisted for over 40 years.1 The deficit stems from an imbalance in the combined goods trade, which includes manufactured products, raw materials, and agricultural products.2 This has lately been a source of concern for some US policymakers.

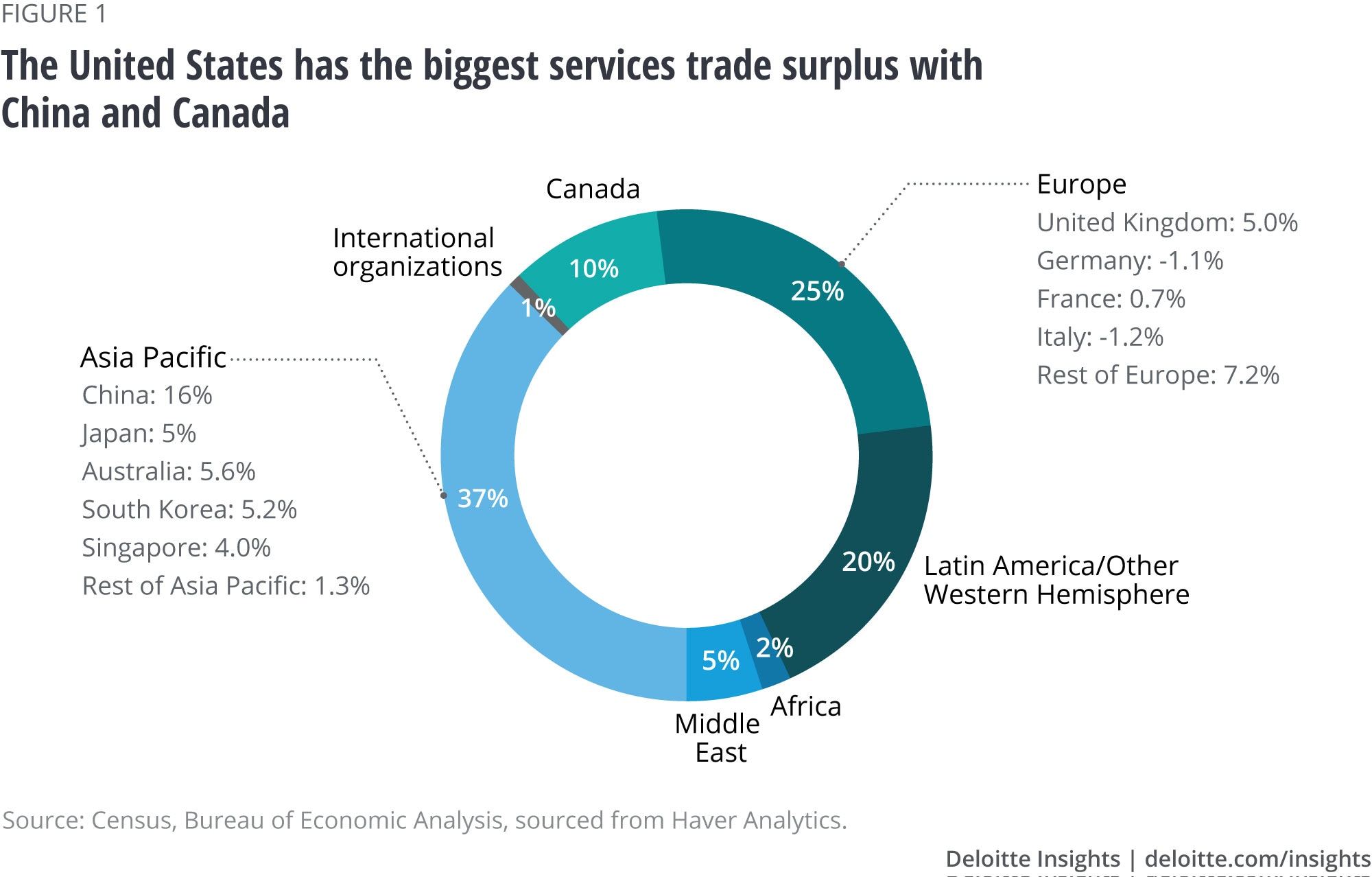

The other major component of trade—services—has bolstered the US economy even during recessions. The United States has had a comparative advantage over other nations since the early 1990s and with the globalization of business, services trade surplus has accelerated since 2005, contributing positively to economic growth. Currently, the United States has a substantial and growing trade surplus with almost all its trading partners (figure 1).

Note: The services sector includes a wide variety of industries including transportation, communication, public utilities, wholesale and retail trade, finance, insurance, real estate, other personal and business services, and government. Indeed, it includes all industries in the economy outside of agriculture, mining, construction, and manufacturing (the goods-producing sector).

Services have immense potential to create growth as well as jobs in the economy. The importance of services to trade is even more evident when one considers that a substantial portion of the value added in goods exports are produced with large amounts of domestic services, such as financial services, real estate, and other business services. In contrast, nearly all of gross services exports represent services value-added, as those sectors use few inputs, either from domestic goods sectors or from abroad.3

Role of services trade

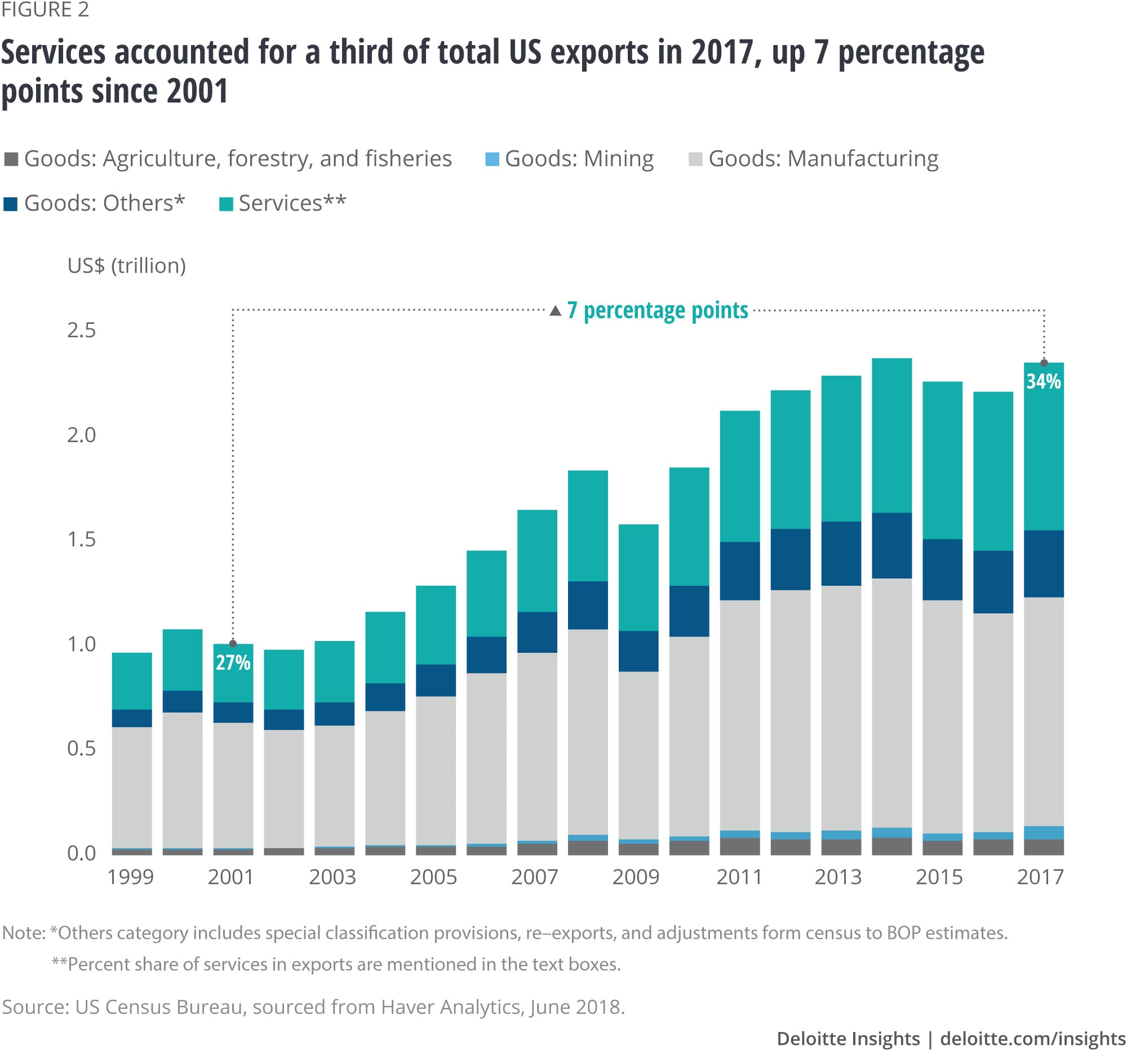

Total exports of goods and services reached nearly $2.4 trillion in 2017, with goods exports contributing close to 65 percent of total exports. Within goods, manufactured products account for a majority, although the share of agricultural exports has also increased in recent years.

However, the overall importance of goods in exports has been steadily decreasing as services have grown in terms of their contribution to value added, exports and trade balance.4 In 2017, services accounted for a third of the total US exports, up from 27 percent in 2001 (figure 2).

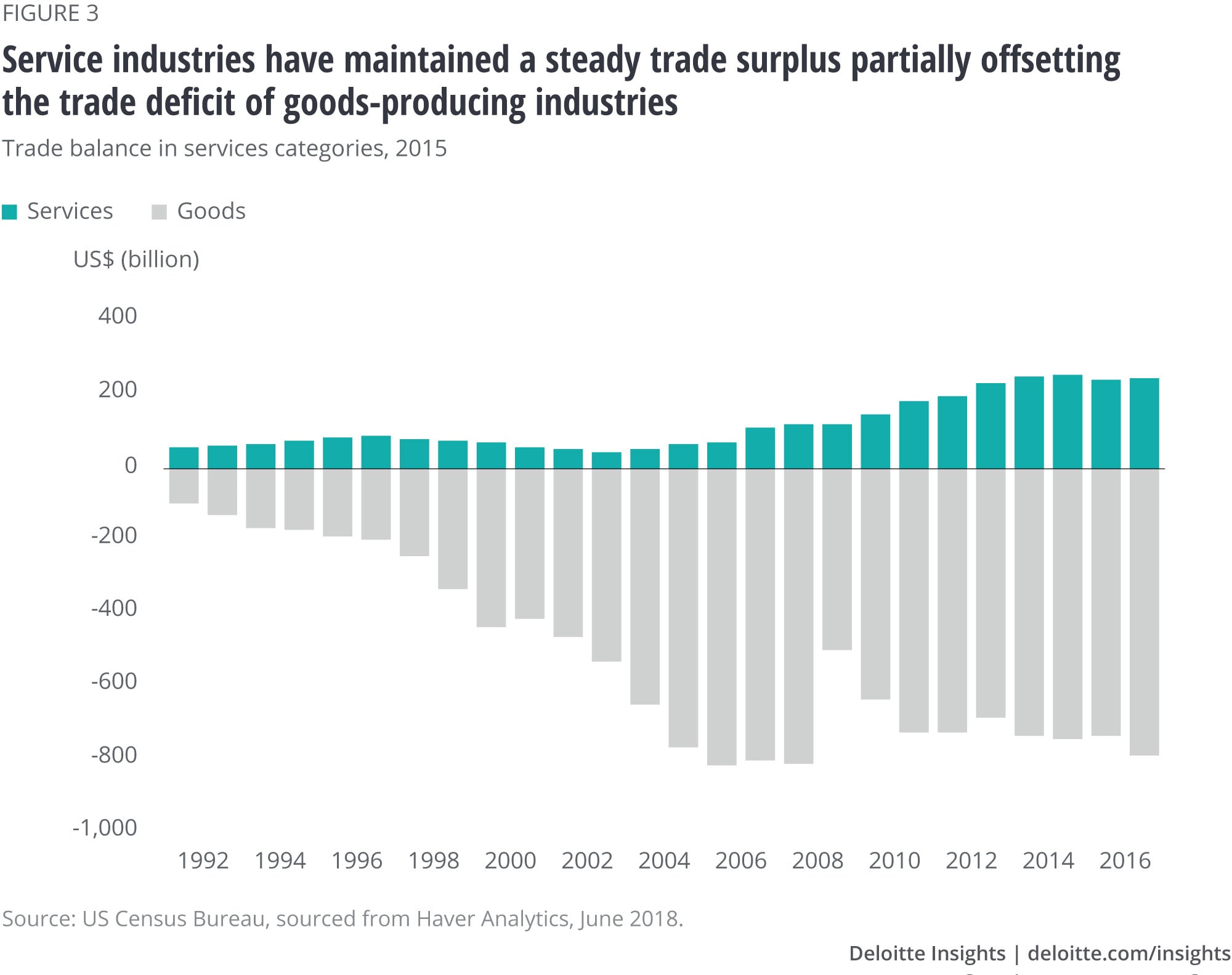

Since 1992, services industries have maintained a steady trade surplus, thereby partially offsetting the trade deficit of goods-producing industries (figure 3). In 2017, the United States exported more services ($798 billion) than it imported ($542 billion), creating a surplus of $255.2 billion (figure 3).

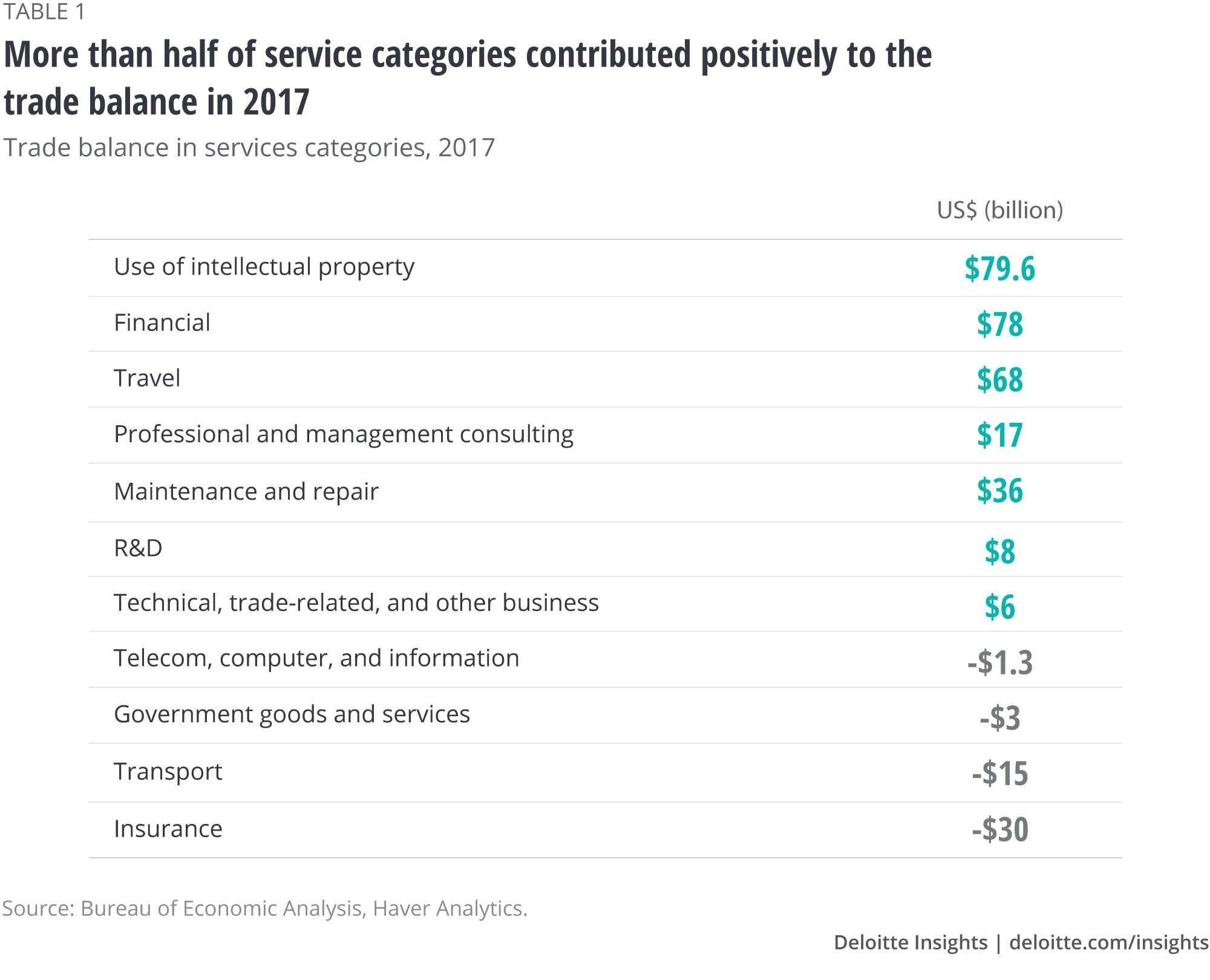

Seven out of 11 service categories contributed positively to the trade balance in 2017, as shown in table 1. The single largest category contributing to the positive trade balance was the use of intellectual property (comprising industrial processes, computer software, trademarks and franchise fees, and audio-visual and related products), followed closely by financial services (comprising securities brokerage, underwriting, and related services; financial management, financial advisory, and custody services; credit card and other credit-related services; and securities lending, electronic funds transfer, and other services). Professional and management consulting services, including services provided by Deloitte, contributed close to $36 billion of the trade surplus in 2017.

Services exports—generating jobs and connecting global value chains

Services exports: An oversized impact on jobs

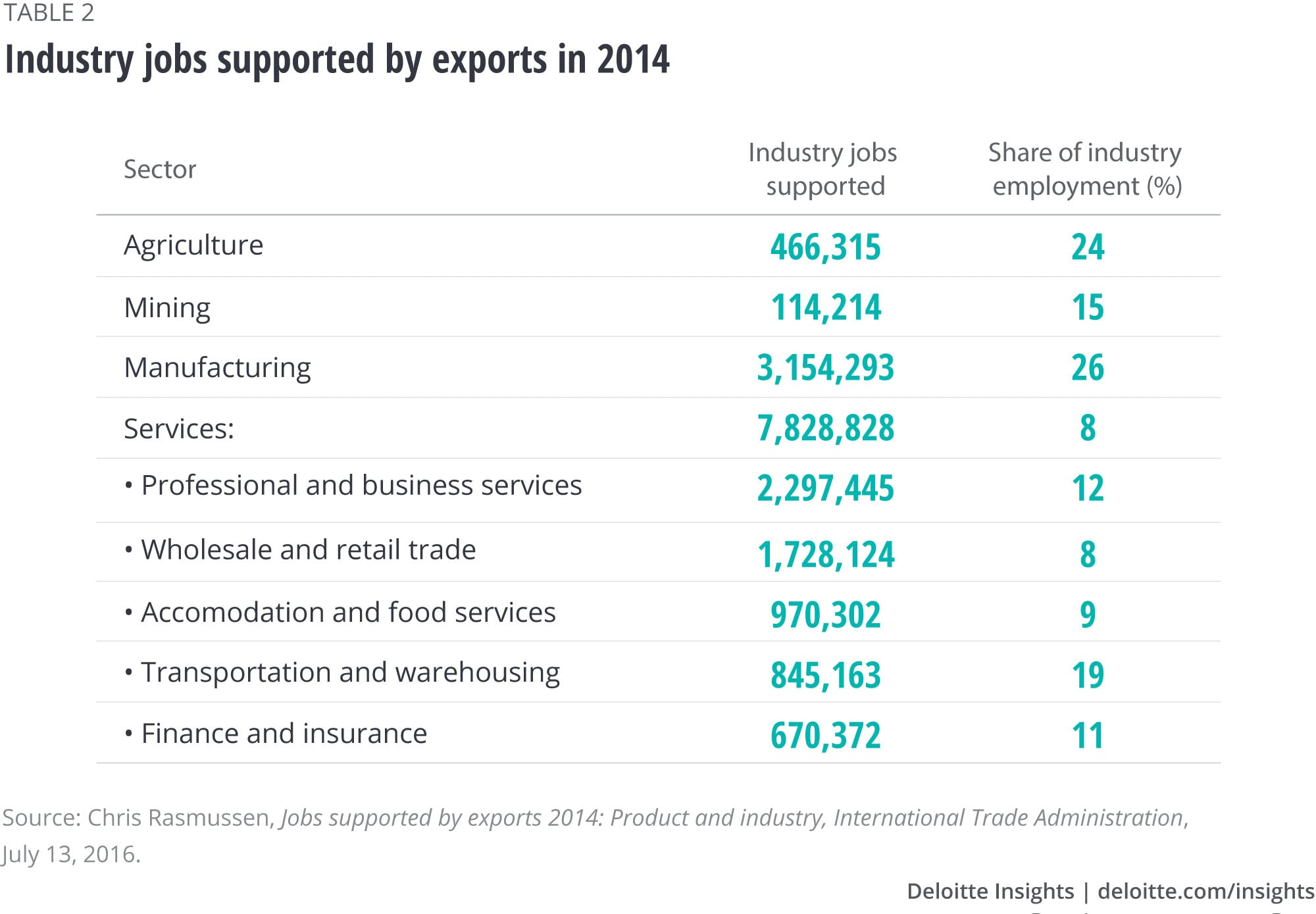

Just as the majority of overall US employment is in the services sector (over 85 percent on average annually in the past seven years), so too is the majority of jobs supported by services exports.5 In 2014, over two-thirds (68 percent) of the export-supported jobs originated from the services sector in contrast to that of 27 percent from the manufacturing sector. Although a larger proportion of manufacturing jobs was supported by exports (26 percent of the total US manufacturing employment), in absolute terms, the total number of manufacturing jobs supported by exports was just over 3 million, as seen in table 2. On the other hand, in services, while only 8 percent of employment was supported by exports, the larger contribution of services to total US employment means that this 8 percent equated to 7.8 million jobs.

As always, the aggregate can mask underlying variation. For instance, 19 percent of transportation and warehousing jobs (845,000) and 12 percent of business and professional services jobs (including jobs in Deloitte, 2.3 million) were accounted for by exports. On the contrary, only 8 percent of wholesale and retail trade employment is driven by exports (table 2).

Services: A critical part of the global value chain

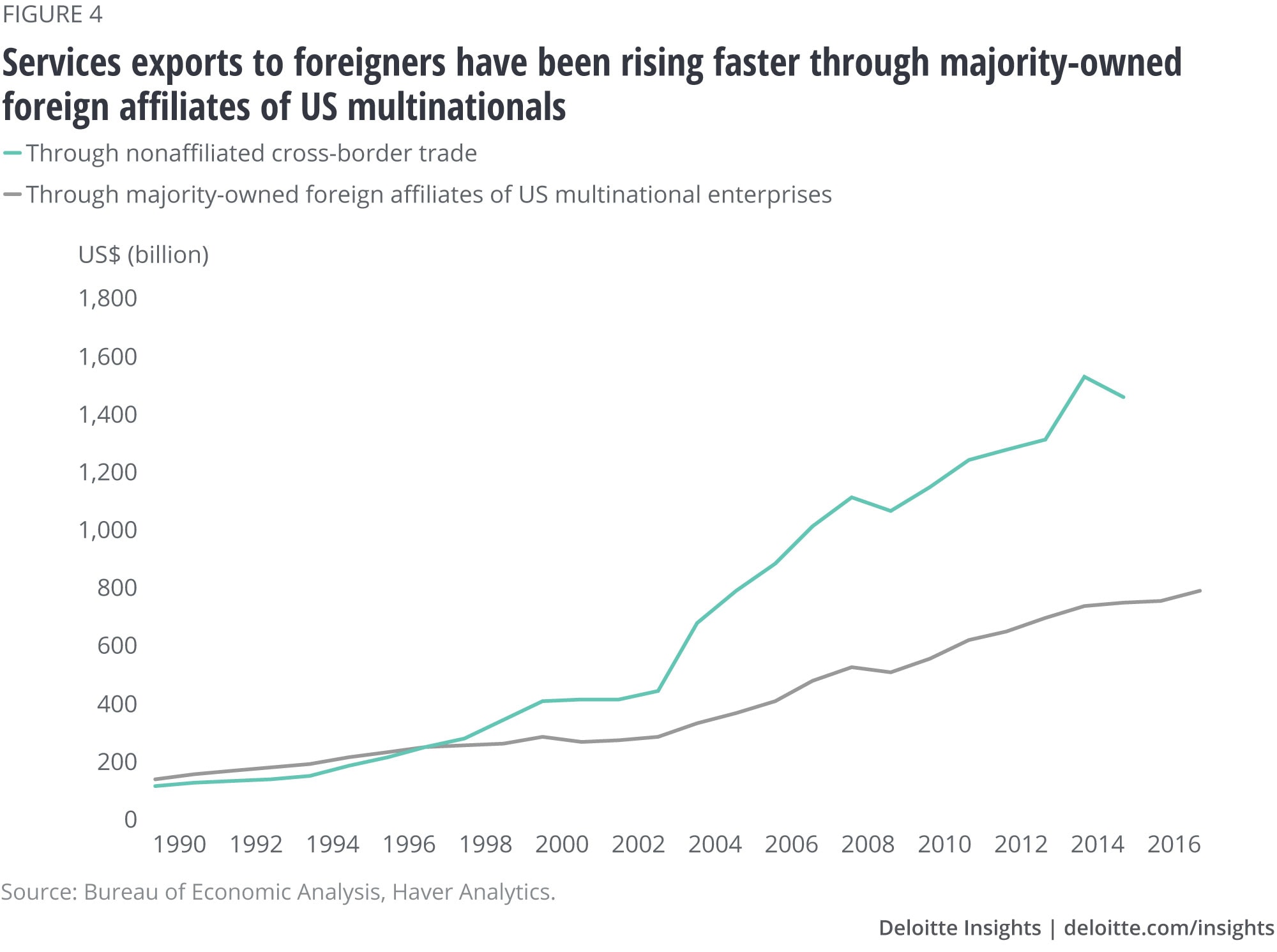

The channel of delivery that services providers use has shifted significantly with the rising importance of affiliate transactions. A large proportion of services exports occur through the commercial presence of US companies in foreign markets (figure 4). Since 1998, exports of services to foreigners through majority-owned foreign affiliates has been rising faster than (non-affiliated) cross-border trade. Moreover, the pace of the former accelerated after 2003 as more US firms are preferring to have a direct presence in the foreign countries where they are doing business. In 2015, US firms traded $1.5 trillion in services through their majority-owned foreign affiliates, compared with only $781 billion in services through (non-affiliated) cross-border trade (figure 4).

Looking forward

The United States has the good fortune to be home to abundant natural resources and inventive technology, but policymakers should consider planning for sustained growth over the long term. If the United States wants continued economic prosperity, then it should consider focusing on industries that are hard to imitate—and many of the services industries fit the bill. The United States may have an advantage over other countries in services: Many services are difficult to imitate and require long-term investment in human capital, something the United States commonly does well. This, in large part, is what makes services key to sustained returns and a rising standard of living.

With their increasing tradability and their rising importance as inputs to traded goods and services, services are poised to likely play an increasingly vital role in the United States’ economic growth and trade. As the international trade conversation continues to evolve, the role of trade in services can provide an opportunity for the United States to bolster its economy and build on a strong track record of growth. We do not minimize the importance of manufacturing to the overall health of the economy, but priorities should also recognize services’ essential role. A healthy services sector is no less vital to a strong US economy than a healthy manufacturing sector. The United States should be at the international negotiating table on both topics.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.