United States Economic Forecast 2nd Quarter 2020

18 minute read

15 June 2020

The pandemic has dealt a massive blow to consumer spending and GDP, and uncertainty about medical and economic issues will likely hold back investment. When will the US economy begin a strong recovery? Probably not before the middle of 2021.

Introduction: The long and the short of the virus

It’s now official: The SARS-CoV-2 virus and its associated disease have dealt a severe short-term blow to the American economy. In two months, Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates showed the economy losing more than 20 million jobs in March and April (about one-seventh of the total number employed in February). As expected, sectors such as arts, entertainment, and recreation services (down 55%) and accommodation and food services (down 47%) were hardest hit. But all private-sector industries saw job losses.1 Ever since mid-March, when states begin to shut down “nonessential” sectors, we’ve known this would happen.

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

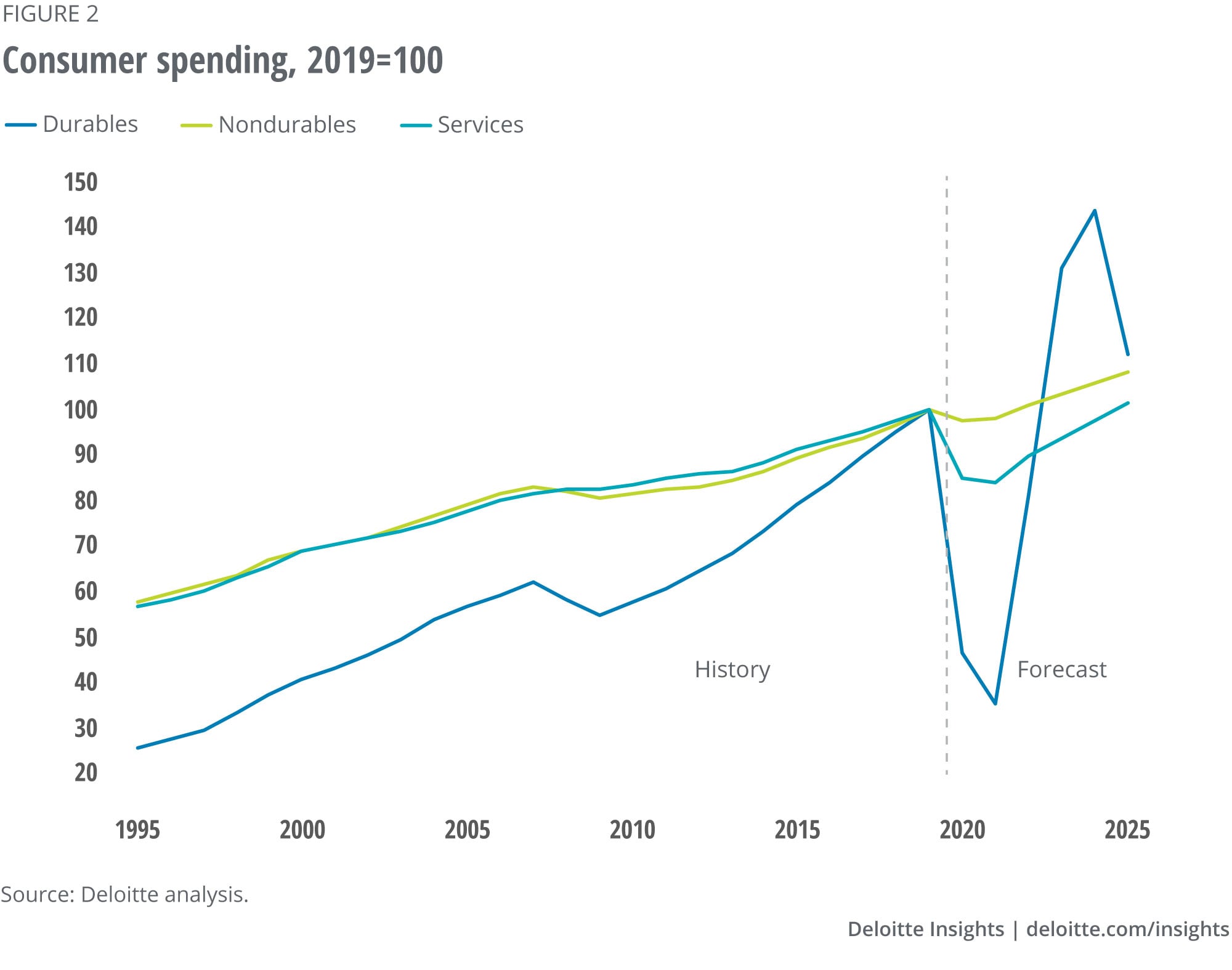

The decline in consumer spending is driving the downturn. Our forecast for near-term consumption is based on an evaluation of consumer spending by detailed sector—and that yields a substantial decline in GDP. Just two key categories of consumer spending—food services and accommodations and recreation services—together account for 8% of GDP. And that doesn’t account for the decline in business spending in those areas. Consumer durables account for another 7% of GDP; sales in that sector have also dropped. And health care services account for 10% of GDP; much of this sector stopped production because of the risk, as well as the need to open up hospital capacity for COVID patients.

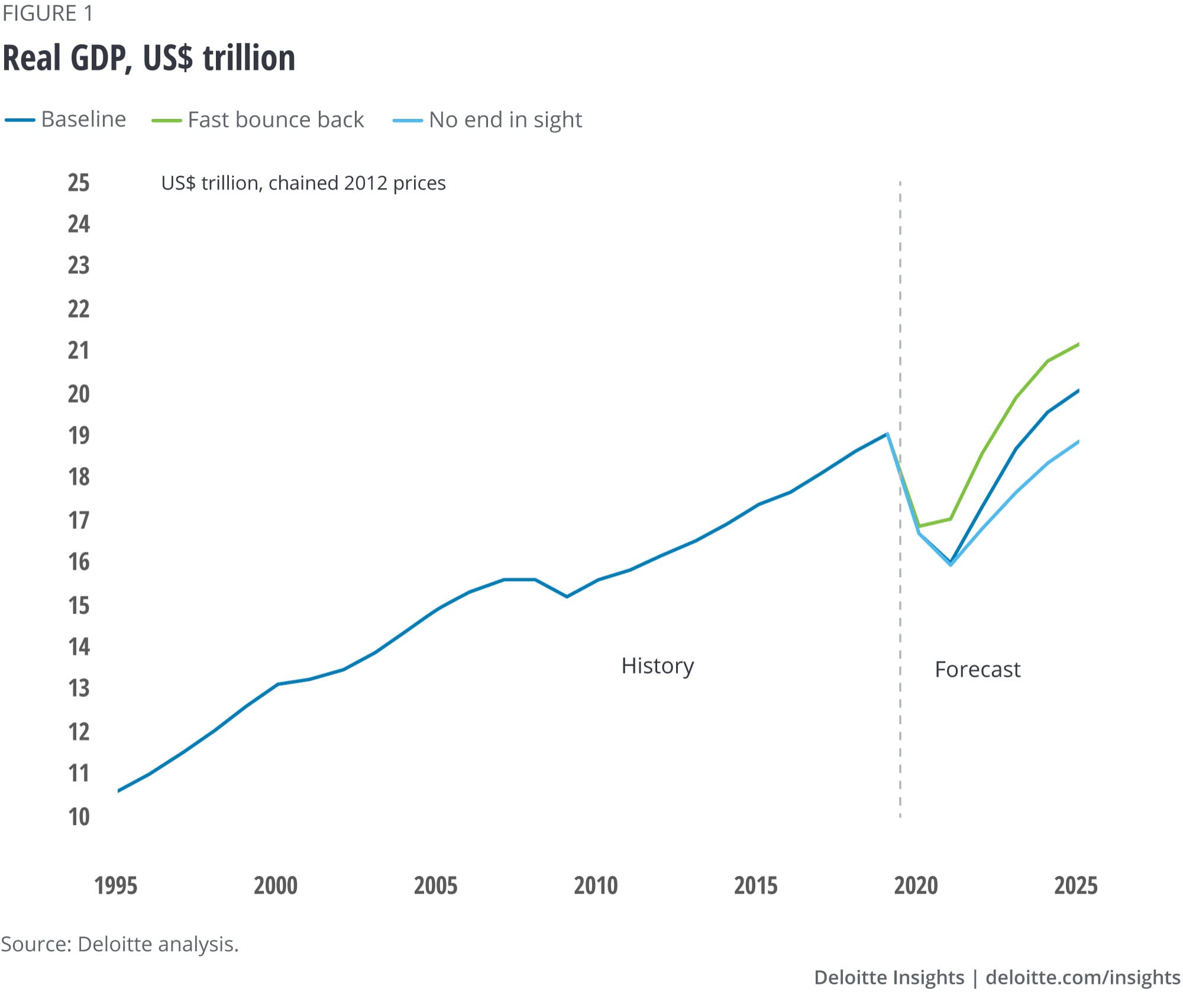

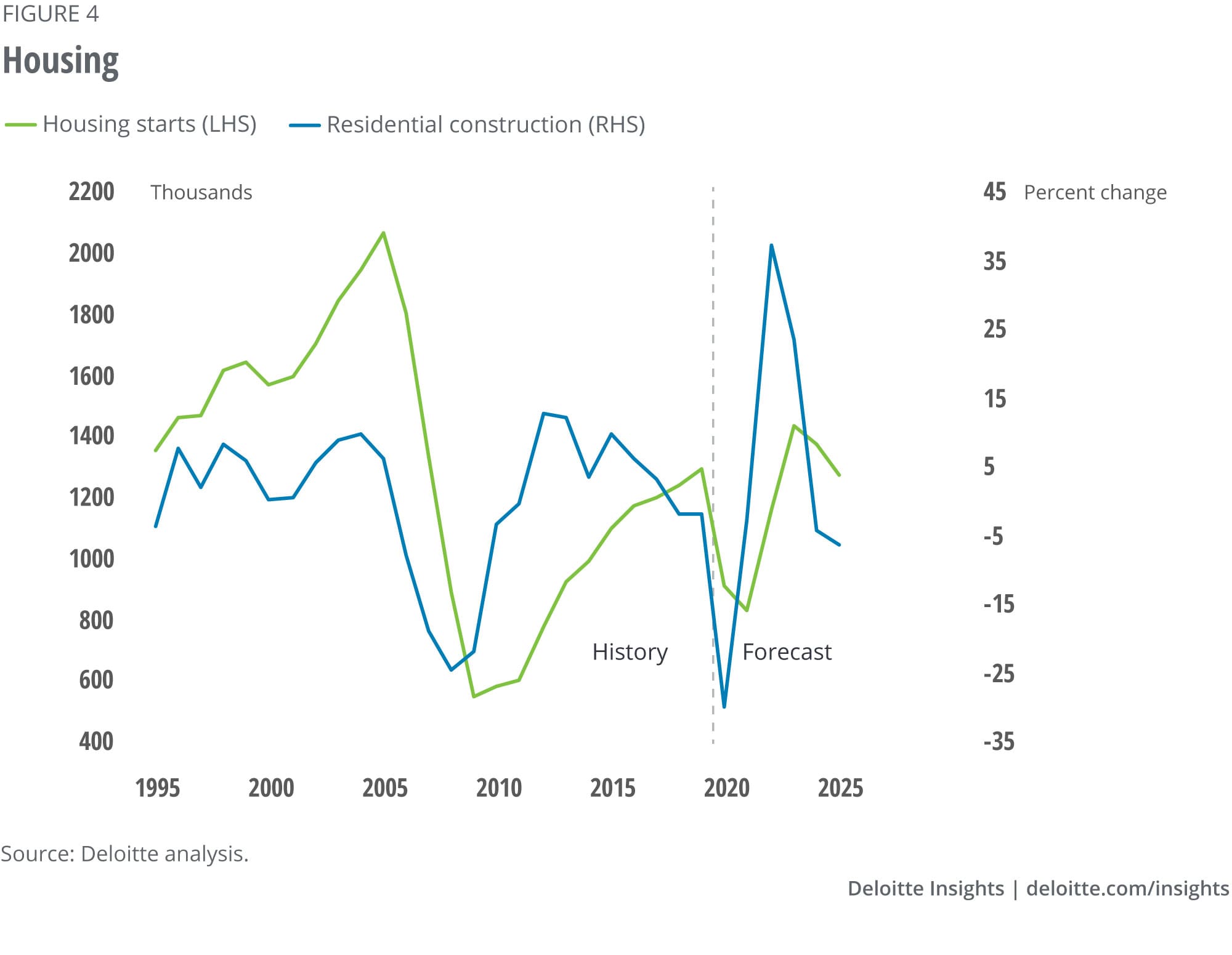

This adds up to a huge decline in consumer spending and GDP; our baseline forecast shows GDP falling over 17% in the first two quarters of 2020. The initial consumption shock is only the start of the trouble: Investment spending is expected to decline, due to lower consumption and the continuing high level of uncertainty. Residential construction is expected to slow as many consumers may find themselves newly unable to afford new houses, even at rock-bottom mortgage rates. And, of course, exports will likely drop as economic activity slows abroad.

We believe that hopes for a quick and strong rebound in the third quarter are optimistic. The speed of recovery—whatever letter-shaped recovery we experience—depends on four key factors:

The medical situation, including the course of the disease itself, improvements in treatment, and the development of a vaccine. Optimistic pictures of a quick recovery (such as our fast bounce back scenario, below) depend critically on medical conditions improving by the third quarter of 2020, and the swift creation of a successful vaccine. While treatment of the disease shows glimmers of promise, vaccines take longer. Even if a vaccine is available as soon as January, as Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health has suggested is a possibility,2 manufacture and deployment of the vaccine globally will still be a matter of years, not months.

How the impact to the economy spreads beyond sectors directly affected by COVID-19. The first round of layoffs may have been concentrated in industries that people began shunning—and were shut down—because of the disease, even before local and state governments imposed lockdowns. There is very likely to be a second round of layoffs and shuttered businesses as aggregate demand crashes. That second round will look more like a traditional recession, with car sales remaining low even when auto dealers reopen, falling house prices even when people can once again consider buying a house, and a decline in people who can afford to fly even if they face little chance of becoming sick from airport crowds and the close quarters of an airplane. The size of this secondary impact, and the permanence, may dictate whether the recovery from this recession is fast or slow. And recent experience has not been positive: The past few recessions have involved slow or “jobless” recoveries,3 and that could well be the case again.

The global impact. Many other developed countries will be reopening before, or at the same time as, the United States. This will help speed the recovery. But some key emerging markets have lagged developed countries in experiencing the disease’s impact,4 and economic problems in emerging markets could prove to be a drag on the US recovery.

Perhaps most important, trust. People have to have trust in four dimensions: trust that their physical space is safe, trust that their financial concerns are being served, trust that their information is secure, and trust that their emotional and societal needs are being safeguarded.5 If public- and private-sector leaders can effectively get people to trust governments and businesses, the economic recovery could take off faster.

This leads us to conclude that the most likely shape for a recovery is a U, as reflected in the baseline forecast. The economy may experience a bounce in Q3, simply from loosening restrictions. But growth will likely remain subdued for several quarters after the bottom in 2020 Q2 until the disease is controlled, the secondary impact is over, trust is regained, and the global economy begins to improve. Differences in assumptions about these factors—and especially about the medical outcome—drive the scenarios.

That’s in the short run. But the long run matters as well. Our five-year forecast horizon forces us to ask the question, “Are we really going to end up where we started?” And the answer is probably no.

There are two reasons why the economy won’t simply go back to where it was. And both suggest that productivity growth and profits are likely to be slow as the economy moves back toward full employment.

First, demand patterns are likely to change, particularly if fighting the disease proves to be a long, hard trek. In the absence of effective near-universal vaccination, sectors that require people to gather in close quarters (such as live entertainment, sports, restaurants, and travel) are likely to struggle even if venues fully open. Consumer spending will therefore shift away from these types of spending; spending on alternatives such as durable goods and housing may therefore grow faster than might otherwise be expected. Savings may also increase, with even affluent consumers simply preferring not to spend given the more limited menu of options available.

Second, business practices are also likely to change, and in ways that may restrain productivity gains. For example, key supply chains may be reshored as business and government newly evaluate the risks of overreliance on overseas manufacturers in areas such as pharmaceuticals. And businesses may rethink the emphasis on just-in-time inventory systems in a world where complex supply chains have been proven to be relatively fragile. Both international trade and supply chain management have contributed to productivity growth over the past few decades,6 and reversing both trends would create a drag on productivity growth. At the extreme, the economy could experience a medium-term trend of declining productivity as companies reengineer to these less productive (but safer) practices.

It all leads to a strong likelihood of a slow recovery and, in the end, GDP at a substantially lower level than the pre-COVID trend suggested. We’ve incorporated this into our forecast by assuming that the baseline is still 5% below our pre-COVID forecast at the end of our five-year outlook, even with unemployment returning to close to full employment. Unfortunately, even under optimistic assumptions, the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its associated disease COVID-19 will do permanent damage to the American economy.

Scenarios

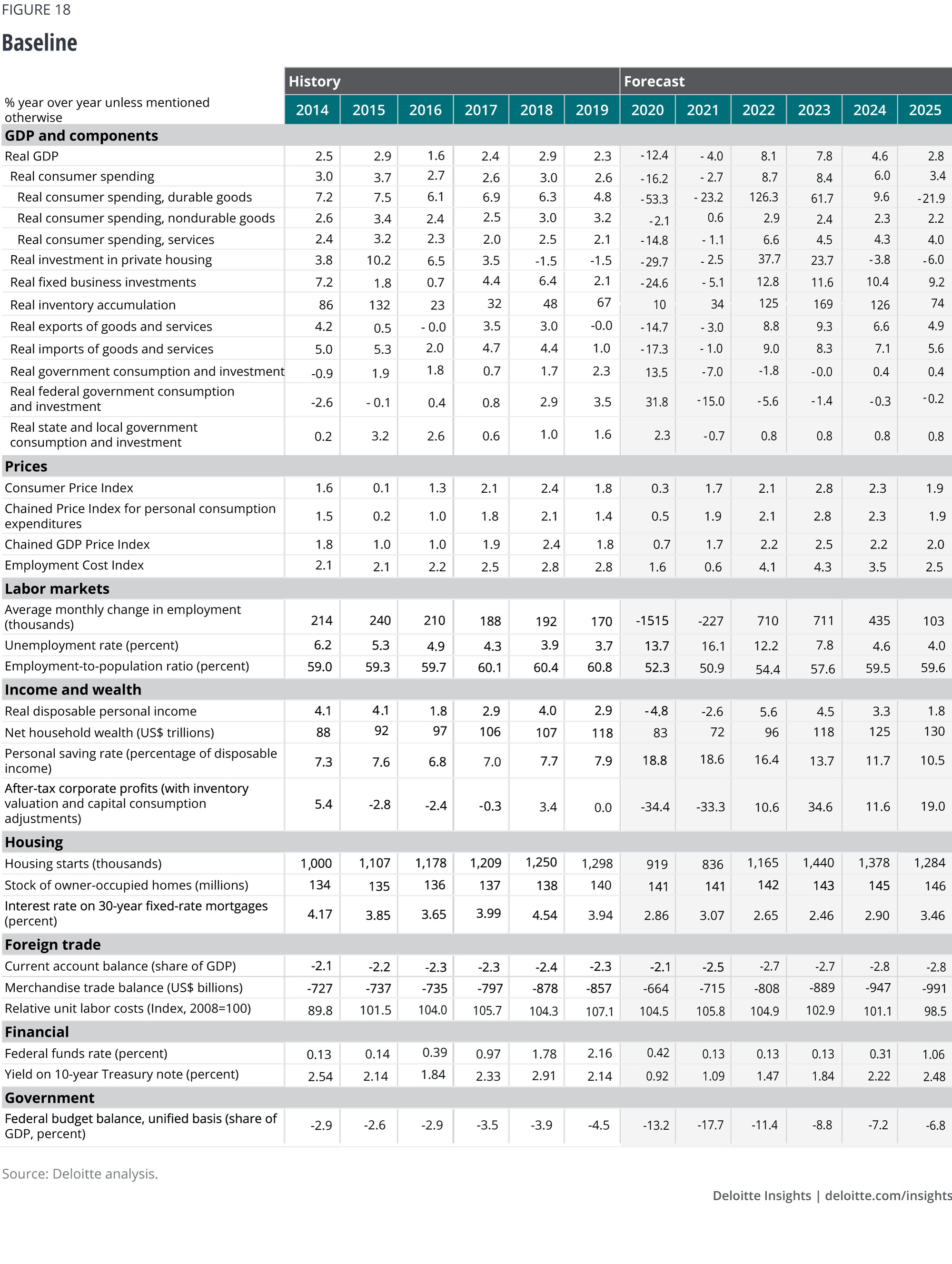

Baseline (70%): The US economy experienced a sharp decline as activity in a number of sectors simply shut down in March 2020. Some of the decline was apparent right away, but most will be felt in the second quarter, when GDP will fall by an unprecedented 16%. The economy will recover in Q3, but the recovery will be offset by another decline in Q4 and slow growth in the following two quarters as the disease proves harder to eradicate than some optimists expect. Recovery will not really get underway until the middle of 2021. Given the low base, GDP growth in 2022–24 may be in the 7–8% range. Growth returns to the pre-COVID level by the end of 2023, with the economy finally reaching full employment by Q1 2025.

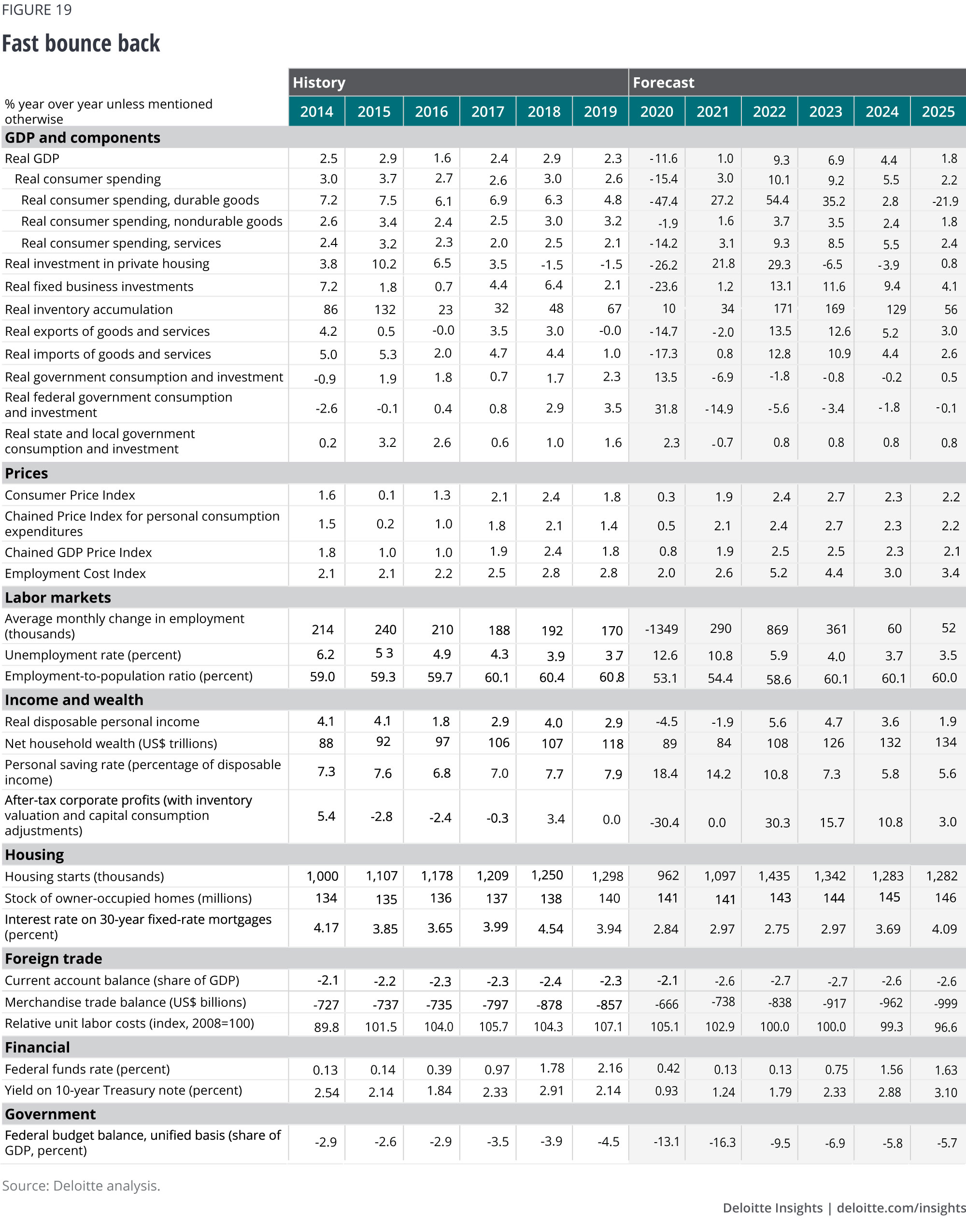

Fast bounce back (5%): Reopening the economy beginning in May proves successful. Government policy has successfully limited the damage to small businesses, and Fed policy has created sufficiently easy credit conditions that companies are able to return quickly to business as usual. Growth picks up in the second half of 2020 and then accelerates in 2021 as a vaccine begins to be widely distributed in January. Economic activity largely returns to the pre-COVID normal by the end of 2022.

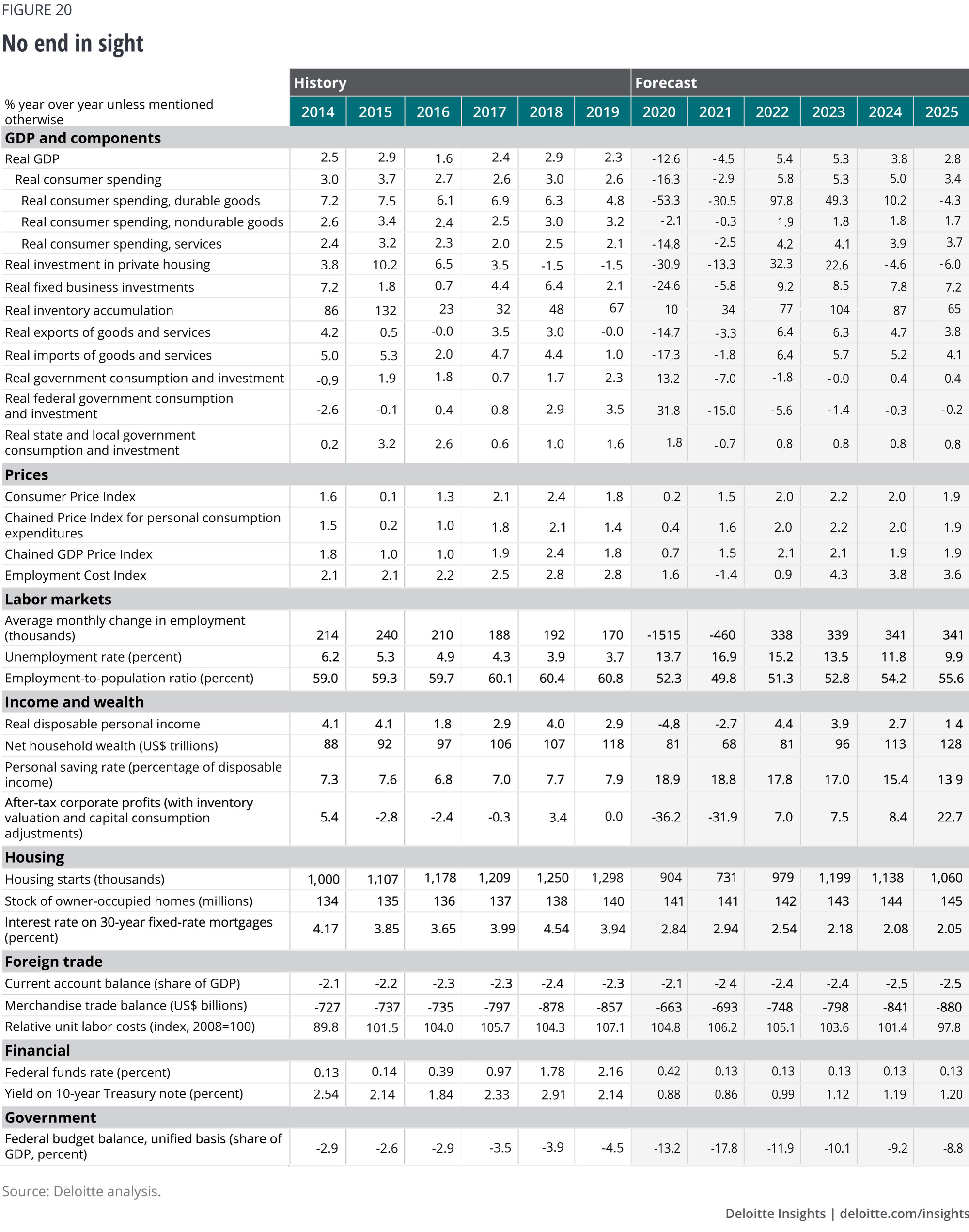

No end in sight (25%): The attempted reopening in the middle of the second quarter proves premature. COVID-19 cases jump, and states are forced to attempt to again limit economic activity. The lack of either treatment options or an effective vaccine means that the cycle of restart attempts and subsequent reclosing continues. This limits the possibility of recovery and erodes trust in institutions; by later reopenings, even as treatment improves, consumers prefer to stay at home in safety rather than take what they have come to believe are unwarranted risks. One quarter of faster growth, in 2020 Q3, is offset by a decline in 2020 Q4 due to fresh outbreaks in the fall. After that, growth remains relatively low, with recovery only starting hesitantly at the end of 2021. By 2025, unemployment remains in double digits, with the level of GDP over 10% below the level it would have reached had the pandemic not occurred.

Sectors

Consumer spending

Consumers put the brakes on spending in March and April.7 While the worst-hit categories were related to the need for social distancing, most (but not quite all) consumer sectors experienced very large declines. In the space of two months, sales at food services and drinking places had fallen 50%, sales at clothing stores were down 89%, and sales at home furnishings and electronics stores were down 66%. All not very surprising given the circumstances.

While the decline was sudden, the reversal is likely to take much longer. Two key factors will prevent a similarly quick return to pre-COVID spending:

- Even if job losses abate by June or July, the huge decline in employment will likely keep a lid on consumer spending. Incomes are being held up (somewhat) by the extraordinary payment of unemployment insurance. But these benefits are temporary, and many households aren’t receiving them. This decline in income will have a multiplier impact on the economy, similar to a decline in government spending, business investment, or exports.

- Consumers will need to be able to trust that going out to spend money won’t come at the risk of catching the disease. The absence of treatments or a vaccine—which is likely to continue for some time—could dissuade many consumers from returning to restaurants, entertainment venues, or even stores. And their eventual return will likely require expensive adjustments to building infrastructure, with facilities able to serve fewer consumers.8

The issue of trust is key to understanding the uncertainty in the consumer forecast. If consumers have reason to distrust businesses and governments, consumer spending will remain weak, and the recovery will be delayed. A second outbreak of the disease in the fall, as some epidemiologists are projecting,9 would itself cut consumer spending—and might also increase consumer distrust, making it that much harder to convince people to return to their previous behavior once medical interventions are available.

And on what will consumers want to spend money? Until medical interventions render considerations about the disease moot, spending will very likely shift away from activities that consumers perceive as risky—entertainment, food service, accommodation—and toward consumption that can take place in a socially distanced way.

In the longer term, the pandemic is expected to exacerbate existing consumer problems. It has thrown the problem of inequality into sharp relief, as the disease strains the budgets and living situations of lower-income households in particular. These are the very people who are less likely to have health insurance—especially after layoffs—and more likely to have the health conditions that complicate recovery from COVID-19.10 And retirement remains a significant issue: Even before the crisis, fewer than four in 10 nonretired adults thought their retirement was on track, with one-quarter of nonretired adults saying they have no retirement savings.11 Low interest rates and the stock market decline will worsen Americans’ preparation for retirement.

Housing

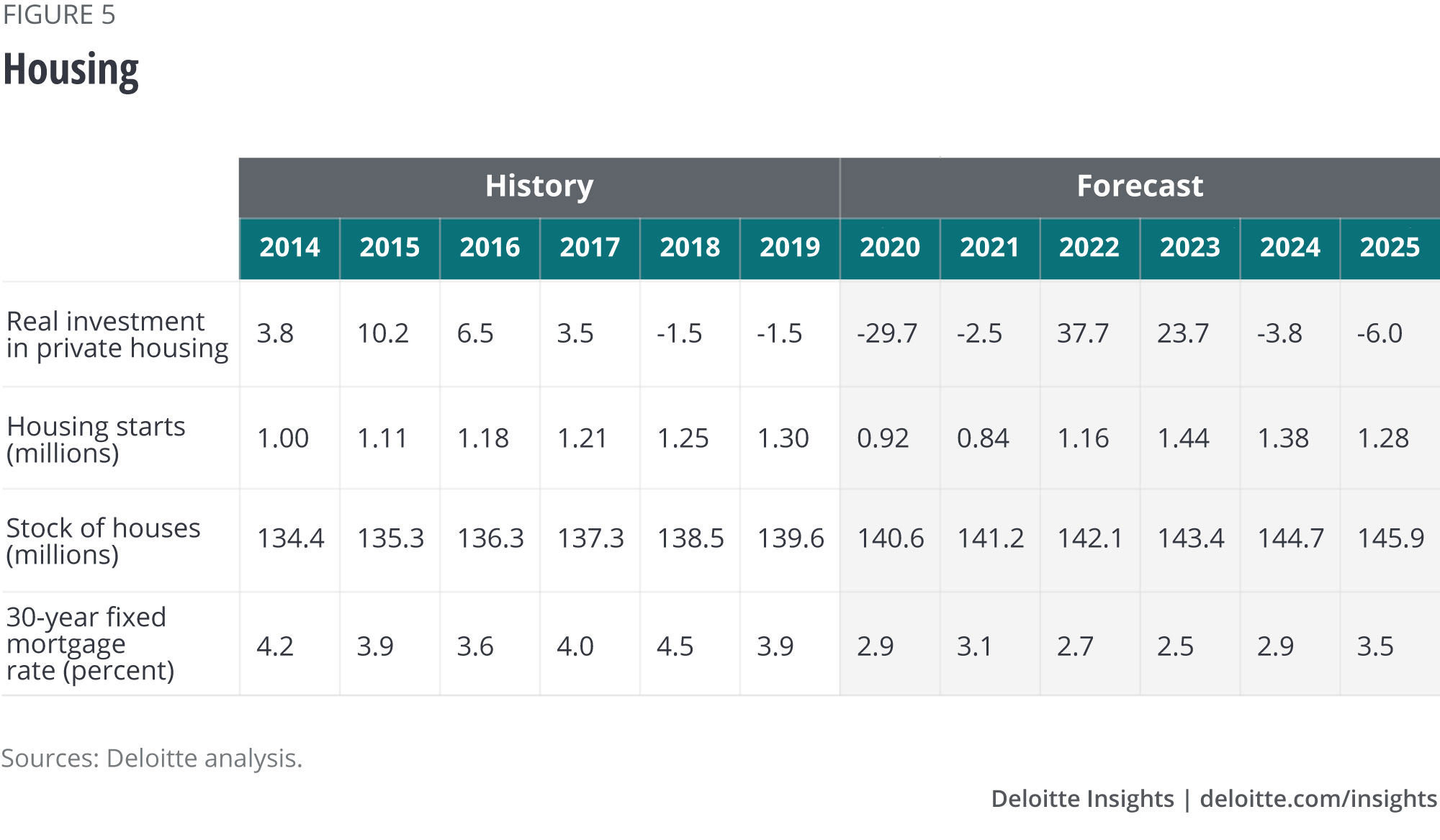

Housing construction was just beginning to show signs of a significant recovery when the pandemic scrambled things. The immediate impact on the sector was surprisingly large: Housing starts fell 43% from February to April, despite many states allowing construction activity to continue. Of course, construction workers don’t exist in a vacuum: With schools shut down and public transportation limited, the sector was not going to escape the pandemic’s economic impact.

Existing home sales have also fallen, but April’s level was still at 75% of the February level. There is good news here: Real estate agents, buyers, and sellers have found ways to operate even if they can’t meet easily or casually. That’s a good sign for the short run, as it suggests that the real estate industry is at least able to keep activity going under the current requirements for social distancing.

The sector’s medium-term outlook, however, is not positive. Our baseline forecast has falling house prices in 2021 and 2022, a consequence of the rise in unemployment. Even with historically low mortgage rates and low house prices, the demand for housing will remain low, simply because of the high unemployment rate. Housing will recover once the labor market recovery is clearly underway.

Housing will eventually recover. But long-run fundamentals ensure that housing does not become a key driver of economic growth in our forecast. Slowing population growth means that the demand for housing will grow slowly in the long run.

Business investment

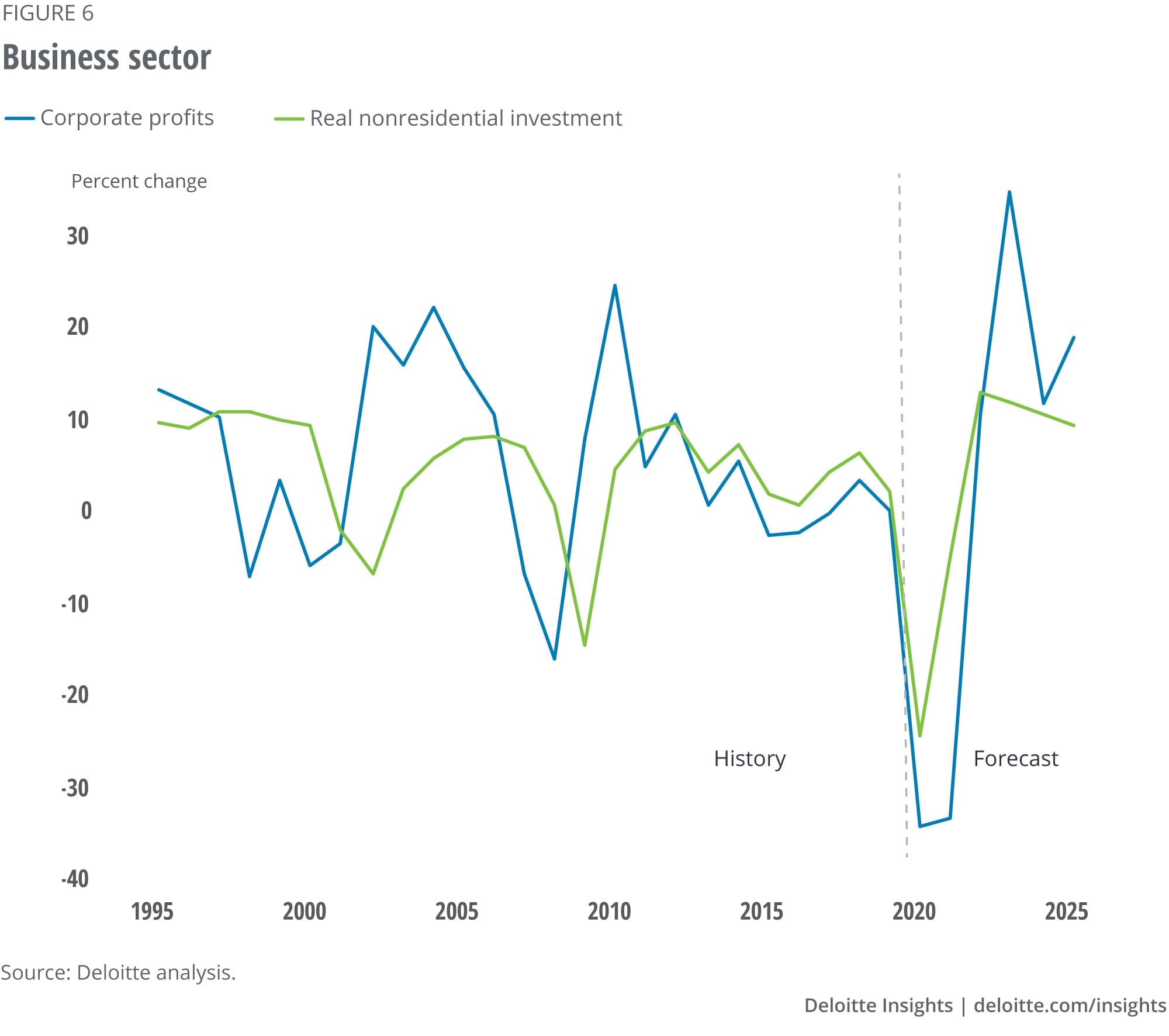

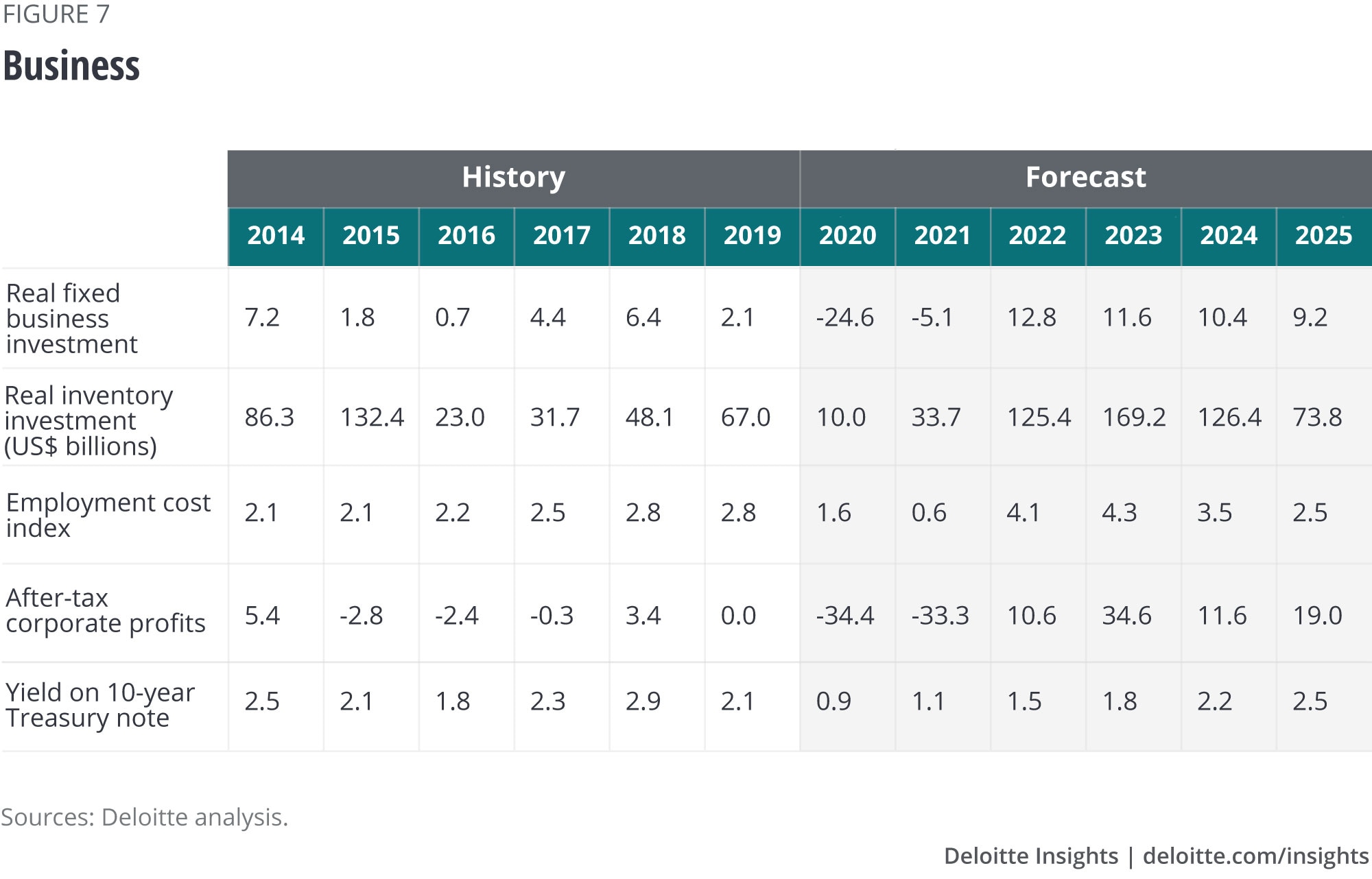

Most business investment was interrupted, like everything else, by the closing of the economy to slow the pandemic’s spread. But businesses are unlikely to resume spending at the same level when state and local officials declare the economy reopened. While some sectors, such as transportation, now have a great deal of excess capacity, expanding capacity anywhere may be a hard sell. Lower consumer spending because of unemployment will reduce the need for additional capacity for producing many goods and services. And key in the short run, businesses face more than the usual amount of uncertainty—and uncertainty plays an important role in business investment.12

Businesses face uncertainty in several dimensions. There is uncertainty about the disease itself, raising difficult-to-answer questions for any business—questions about operations, customers, and costs. There are questions about the financial system, and the ability to fund new investments. And there are questions about the recovery—how quickly the unemployed will be able to find new jobs once the crisis is passed, and whether the government response will help the recovery.

Under these circumstances, business investment is likely to remain muted for some time. The forecast assumes that business spending will remain relatively soft until the overall economy begins to steadily recover in mid-2021.

At that point, there may be reasons for businesses to begin increasing investment. Some of those reasons, unfortunately, may actually help to reduce productivity. First, businesses will be required to make investments to prevent disease that do not improve productivity or add to profits. Second, government policy may encourage reshoring in “strategic” industries, especially medically related industries such as instruments and pharmaceuticals, arguing that it’s worth some inefficiency to obtain better national control over these areas in a future crisis. Third, businesses are likely to consider investing in ways to make their supply chains more robust, including reshoring, diversifying suppliers, and/or increasing inventories of critical products. All of these will reduce efficiency and add to costs in normal operation but prevent extreme events from shutting down production.

The United States may therefore experience relatively high levels of investment in this recovery. But it may not achieve the higher productivity we would normally expect that investment to generate.

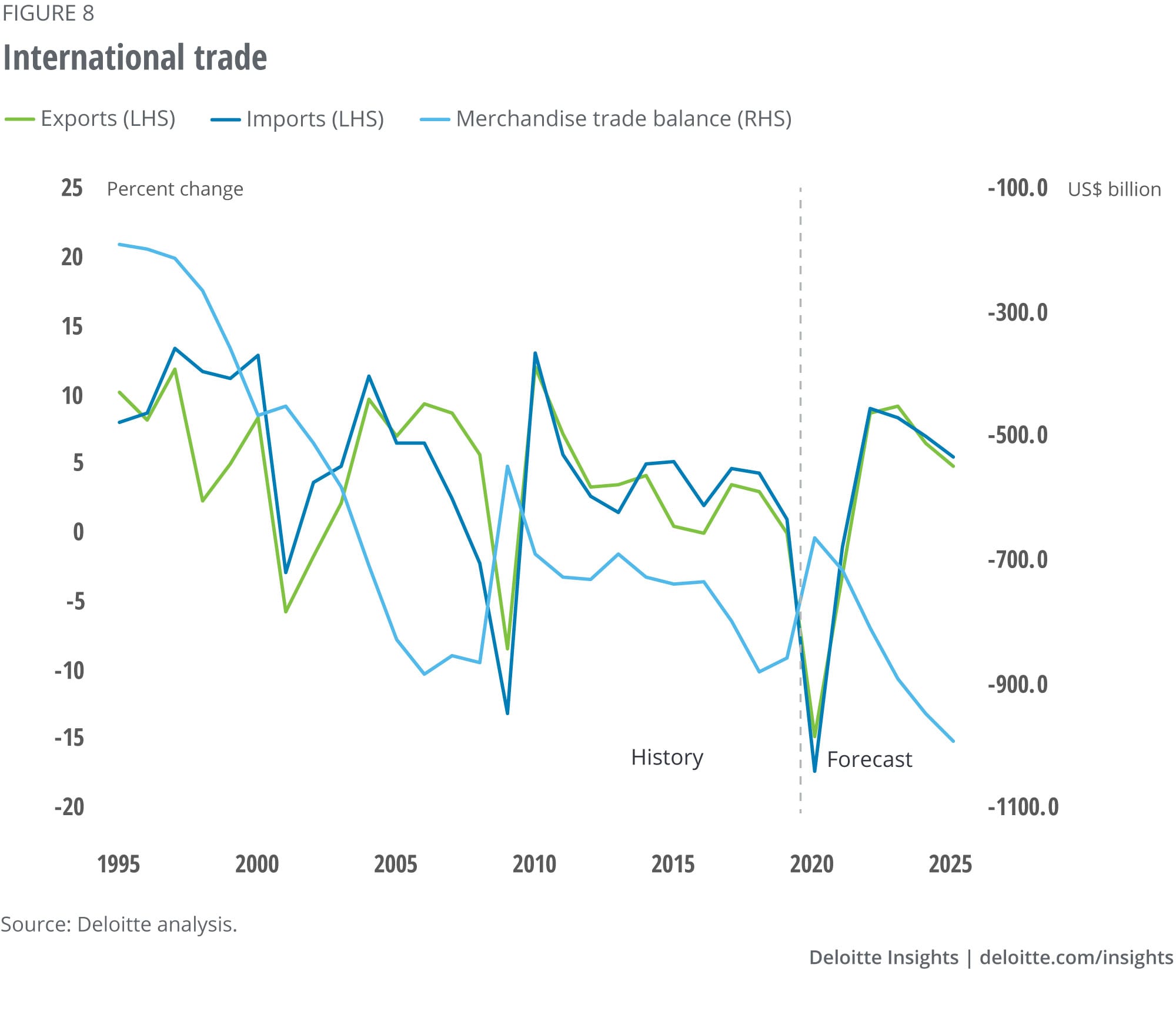

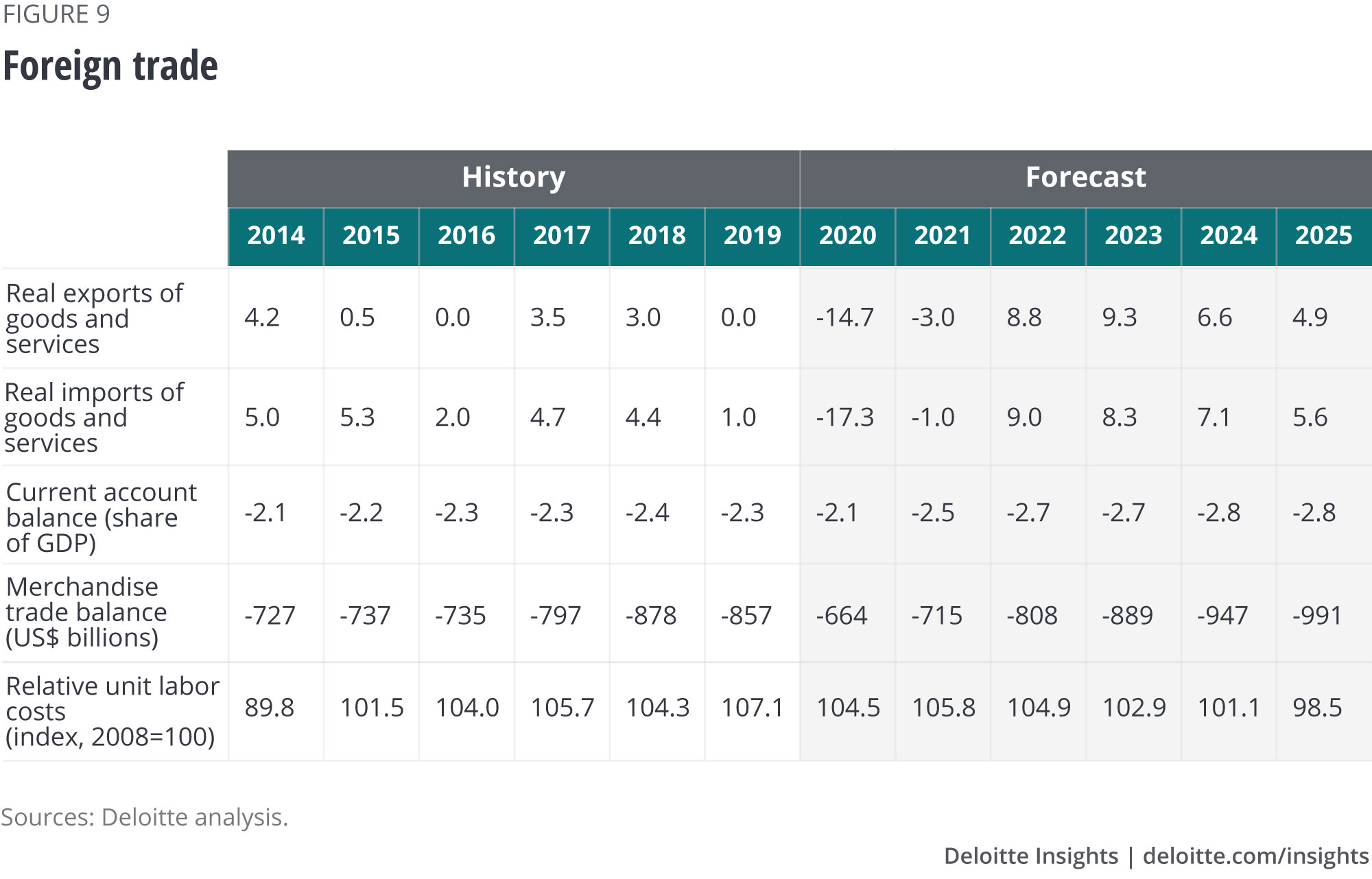

Foreign trade

Over the past few years, analysts have begun to face the possibility of deglobalization. The previous decades saw global exports grow from 13% of global GDP (in 1970) to 34% of GDP (in 2012). But globalization then began to stall, the share of exports in global GDP started to fall, and opponents of freer trade have taken power in key countries (most notably the United States and the United Kingdom), suggesting that the policies that fostered globalization may change in the future.

COVID-19 may have accelerated this trend. Although the pandemic is a global phenomenon, leaders have made major decisions about how to fight it on a country-by-country basis. Some analysts foresee the pandemic accelerating deglobalization as national governments begin to compete for scarce medical supplies and even knowledge.13 And in the midst of the pandemic, the US-China trade war shows no sign of abating. That’s not a good sign for the future of international cooperation and continued open borders.

It’s impossible, of course, to simply and quickly rebuild supply chains to reduce foreign dependence. American companies will continue to source from China in the coming years. But companies will likely begin to reduce their dependence on foreign suppliers, or attempt to have a portfolio of suppliers rather than a single source, even if the single source is the cheapest. Reengineering the supply chain will inevitably mean a rise in overall costs. Just as the “China price” held inflation in check for years, an attempt to avoid being dependent on China might just create inflation pressures in the later years of our forecast horizon. And if markets won’t accept inflation, companies will have to accept lower profits in order to diversify supply chains. Globalization has offered a comparatively painless way to improve most people’s standard of living, while deglobalization will involve painful costs and limit real income growth during the recovery.

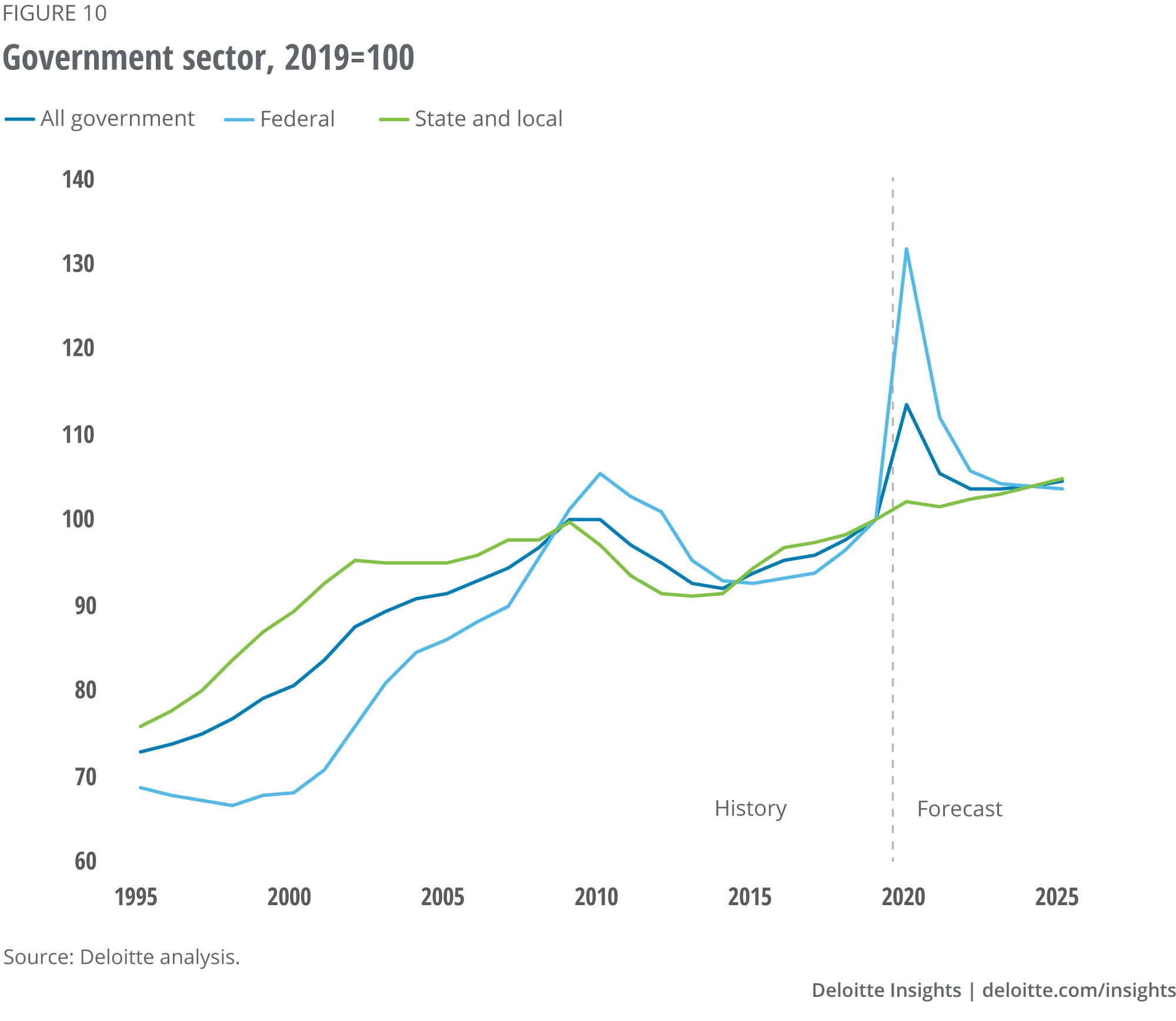

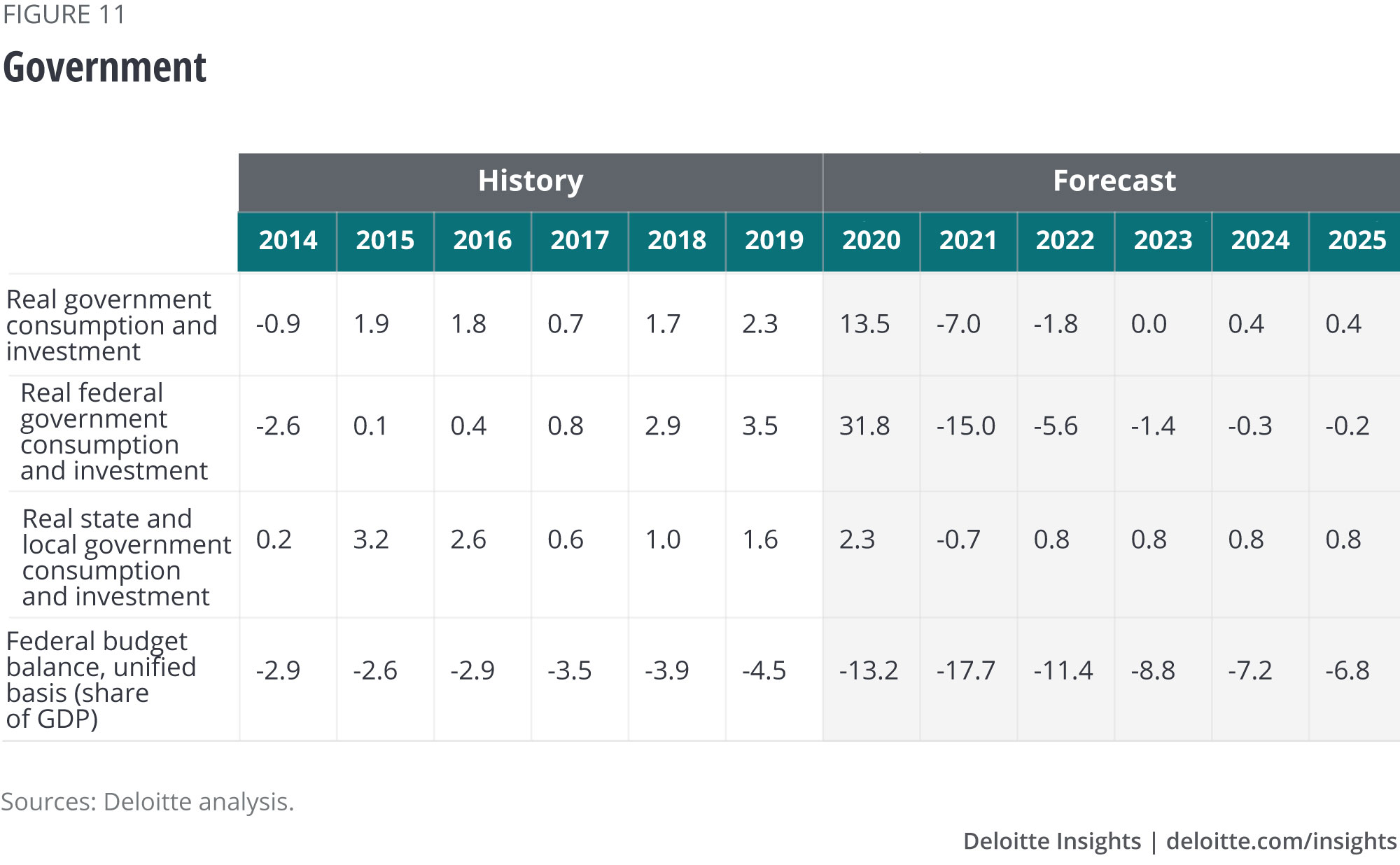

Government

US government budget policy has become completely focused on managing the economic crisis. So far, Congress has passed four spending bills, amounting to almost US$3 trillion in additional spending and revenue cuts. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell explained these bills’ intended economic impact: “This is not even a stimulus package. It is emergency relief.”14 The difference matters. Much of the spending is designed to keep economic actors—businesses and workers—frozen in place until the economy can reopen. The enhancement of unemployment insurance, for example, is meant to pay people not to work. That’s very different from how we normally view the unemployment insurance program. But encouraging people to work makes little sense when the economy needs to remain relatively dormant to reduce the spread of the disease.

This raises the important question of what the government should do once the economy is able to reopen. There are two possibilities:

- The economy may need no stimulus. This optimistic view assumes that reopening will allow businesses to quickly rehire workers and resume pre-pandemic operations, and that economic growth will be very strong.

- The economy may remain stagnant even without the disease hanging over it. Despite the government’s efforts, some (many?) businesses may be unable to reopen. Changed consumer demand and business operations might require a period of adjustment. In this case, traditional government stimulus may be necessary to avoid persistent high unemployment.

If a stimulus is required, the composition of the package will determine its effectiveness. The Congressional Budget Office suggests that the multiplier, or bang for the buck, of federal spending on GDP is higher from direct federal spending, or transfers to state and local governments, for infrastructure than for tax cuts.15 An effective stimulus will likely focus on those areas.

All of this spending has ballooned the budget deficit. The Congressional Budget Office expects federal debt held by the public to equal over 100% of GDP by the end of the current fiscal year. The Deloitte baseline shows the annual federal deficit remaining at over US$1.5 trillion through 2025, the end of our forecast horizon. This is larger than the largest deficit run during the global financial crisis.

This inevitably raises the question of whether the US government can continue to borrow at such a pace. The answer is that it can—until investors lose confidence. At this point, investors show no sign of concern about US debt. In fact, very low interest rates on US government debt indicate that the world wants more, not less, US debt. We anticipate no problem over the forecast horizon. But the government will eventually be faced with a crisis if it does not eventually find ways to reduce the deficit and consequent borrowing. That crisis may be many years away, and current conditions argue for waiting. It would not be a good idea to wait too long once those conditions lift.

On the other hand, the finances of state and local governments may quickly turn into a serious problem. State governments are generally required to operate under balanced budgets, and most state fiscal years start on June 1. The 23% drop in national retail sales between February and March is already translating to a large decline in sales tax receipts, and the high unemployment rate will reduce income tax collections. Those are the main revenue sources for state governments. Many states have little choice but to contemplate substantial spending cuts16—cuts that would both worsen and lengthen the recession.

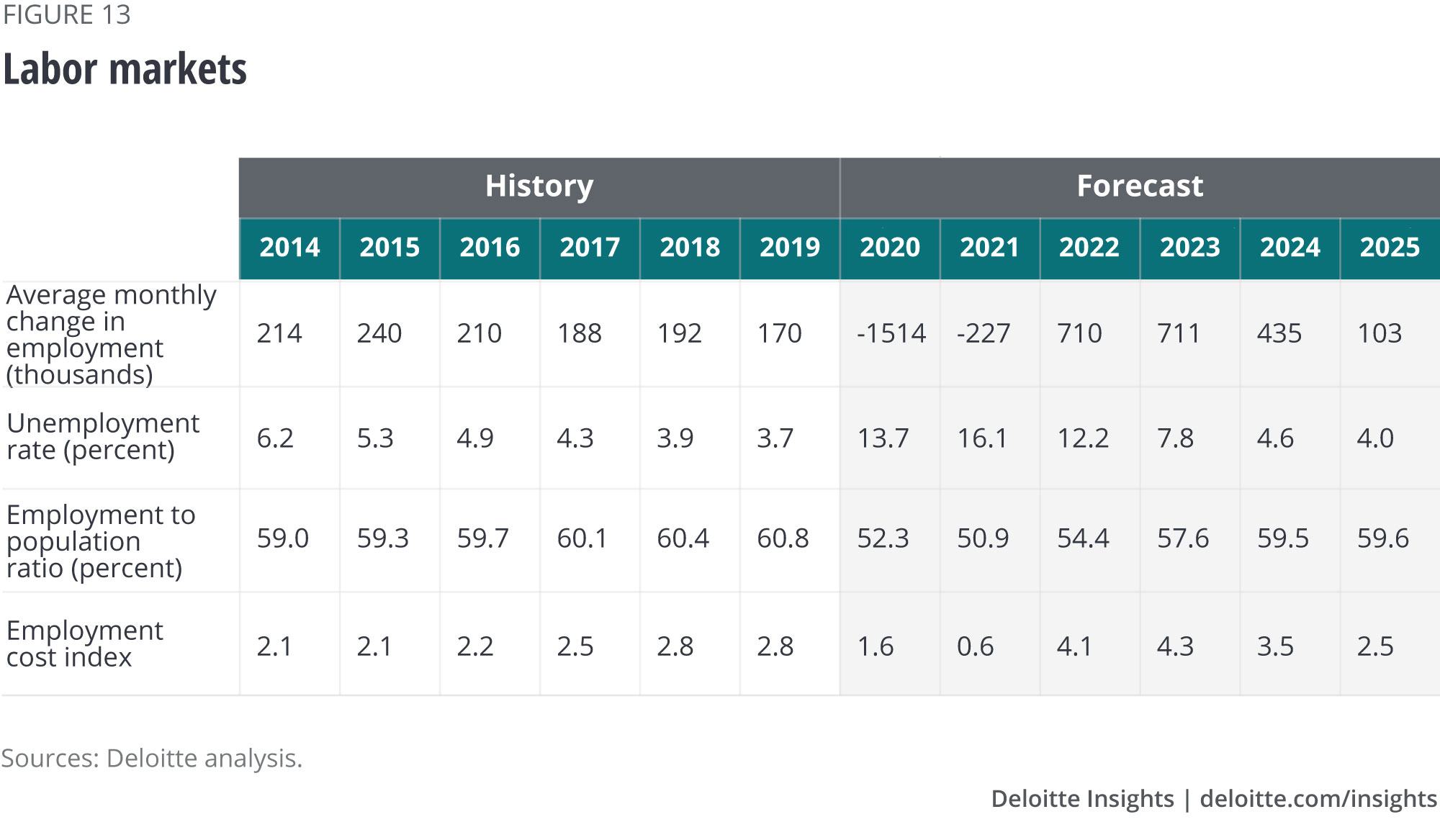

Labor markets

The great layoff of 2020 saw employment plunge by more than 20 million. Half of everybody working in arts, entertainment, and recreation and in food services and accommodation was laid off, but employment in all industries fell. Most industries experienced a decline of more than 10%. That’s a massive hole, and it seems unlikely that it’s at an end. Enhanced unemployment insurance is softening the income blow quite a bit—by some estimates, UI payments made up half the total lost personal income of the unemployed in April.17 But additional rounds of layoffs are likely as jobless households hold back on their spending—and even households with employed members spend less.

Bringing all those people back to work is likely to prove very challenging. As long as the disease remains a significant issue, demand in the most affected industries will continue to lag. That means that many people who were employed in those industries will need to seek jobs in other industries (and perhaps other occupations).

At the same time, businesses will be looking for people—but in different industries and occupations. Efforts to reshore parts of the supply chain, and to build more robust manufacturing systems, will likely mean that jobs will become available in manufacturing and related industries. How to entice people to switch to manufacturing from, say, food service and accommodation? The lack of opportunities in the old areas will help, but many businesses in manufacturing may need to invest substantial effort—and perhaps higher wages—to attract workers, even as unemployment remains high.

Such labor market adjustments are usually slow to occur, one reason why we expect the overall economic recovery to be relatively slow. Promoting more efficient labor markets might help to speed the recovery—but it will mean admitting that the pre-pandemic economy will never return. That might be a hard pill for workers and policymakers to swallow.

Financial markets

The Fed’s operations have been one of the bright spots of the response to the pandemic. When the disease first started spreading in the United States, there was a significant possibility that a financial market meltdown could have added to the country’s economic problems. The Fed’s prompt and strong actions kept financial markets liquid and operating, preventing that additional level of pain.

There was a cost, of course: the Fed’s intervention in many different markets. The traditional concerns about the Fed buying private assets have gone out the window, and the Fed has created methods for direct lending from US states, counties, and cities (Municipal Liquidity Facility), small and medium-sized businesses (Main Street Lending Program), and purchases of corporate bonds (Primary and Secondary Corporate Credit Facilities).18 This is unprecedented: The Fed has traditionally avoided lending directly, avoiding the complications of dealing with nonfinancial firms. Other programs are aimed at stabilizing specific financial markets. Although the volume of lending for many of these facilities is still at a fraction of the announced level, the Fed’s willingness to lend has calmed credit markets.

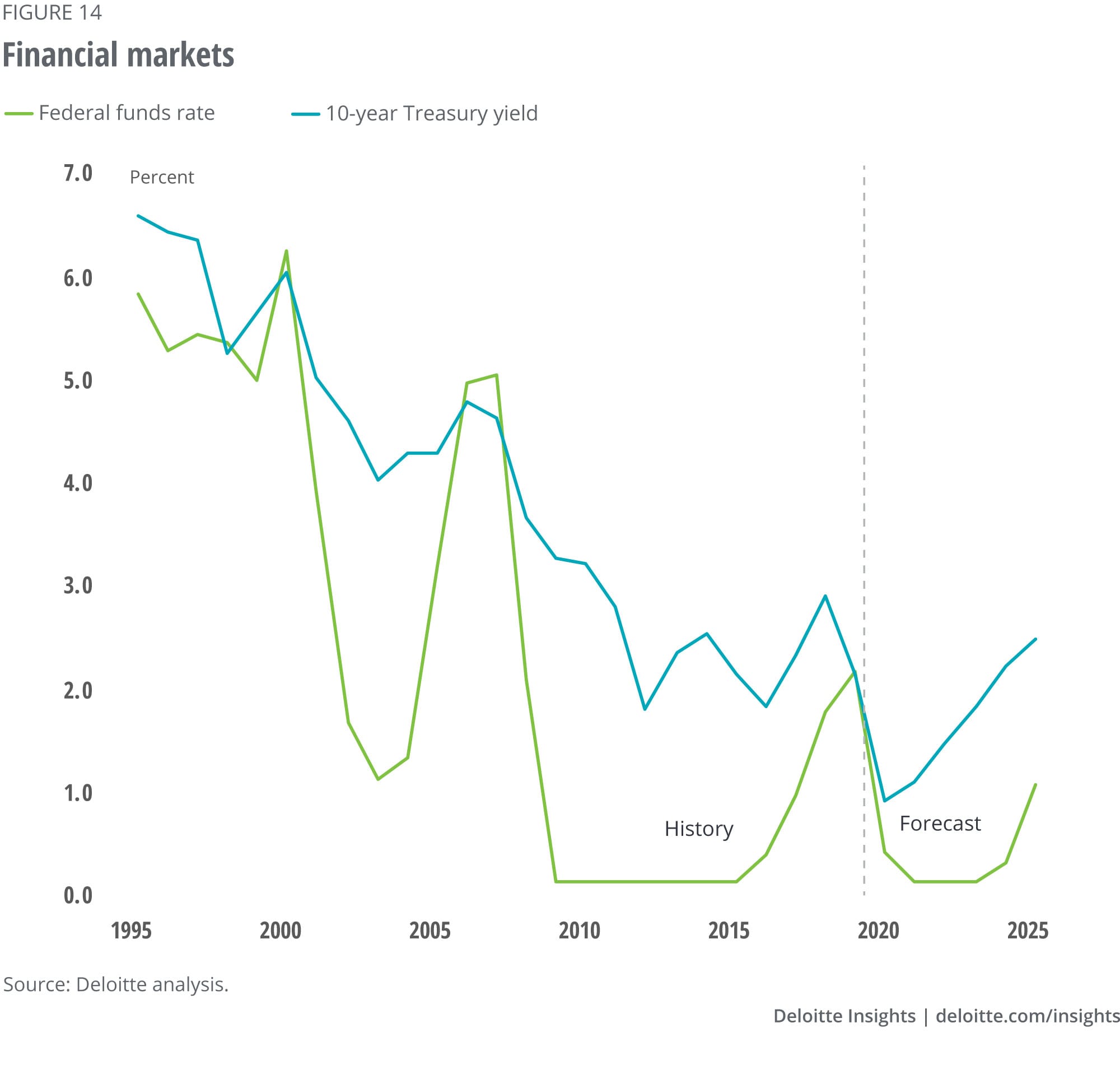

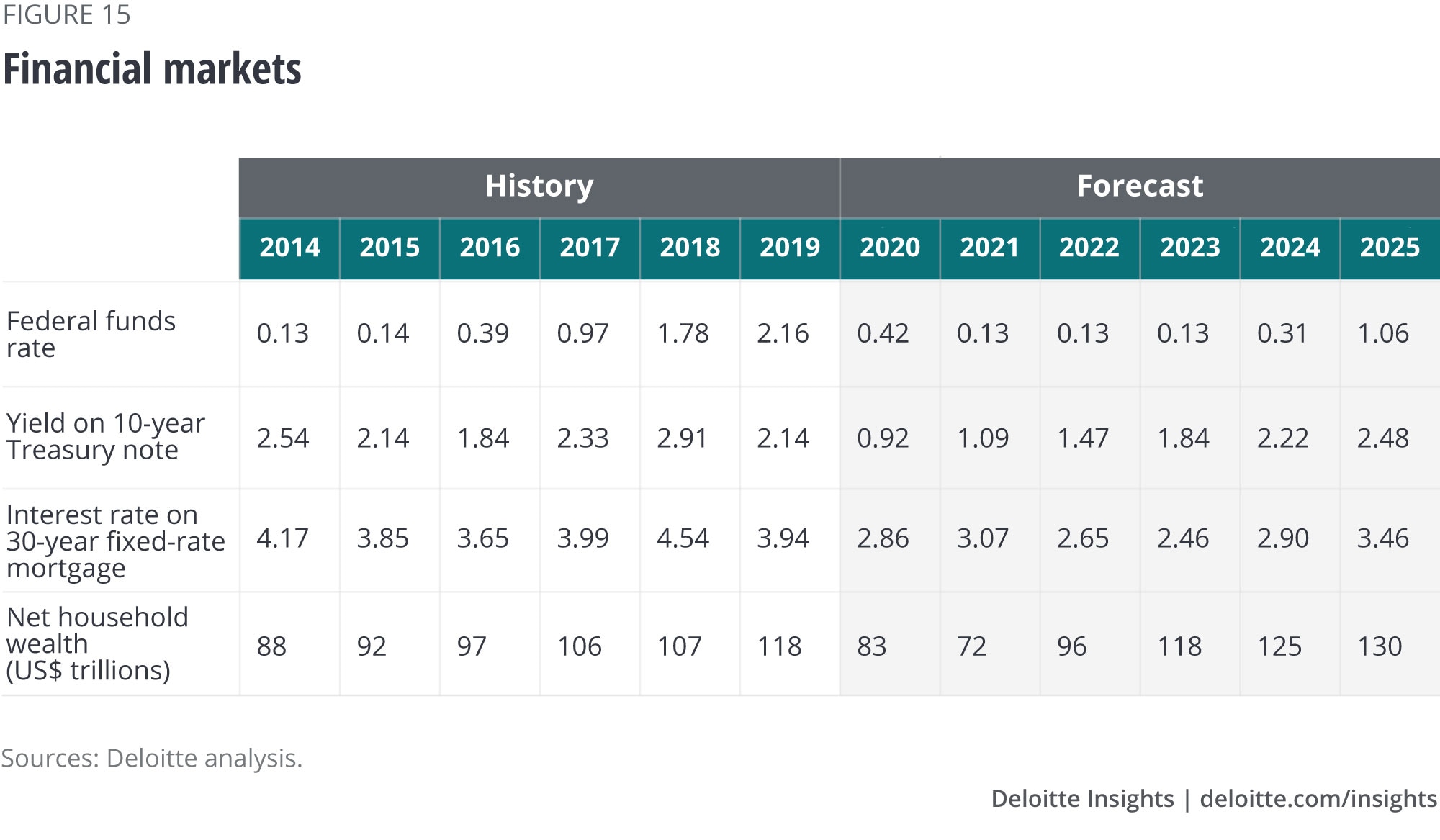

In the longer term, the Fed will want to wean markets off of its aid. But this is likely several years away. And since sales of these assets will precede hiking the Fed funds rate, we have assumed that the funds rate remains near zero over the five-year forecast horizon. We do assume a slow rise in long-term interest rates as financial markets “normalize.” But that leaves the 10-year Treasury yield at 2.5% by 2025. Interest rates are always the least certain part of any forecast: Any significant news could, and will, alter interest rates significantly.

Prices

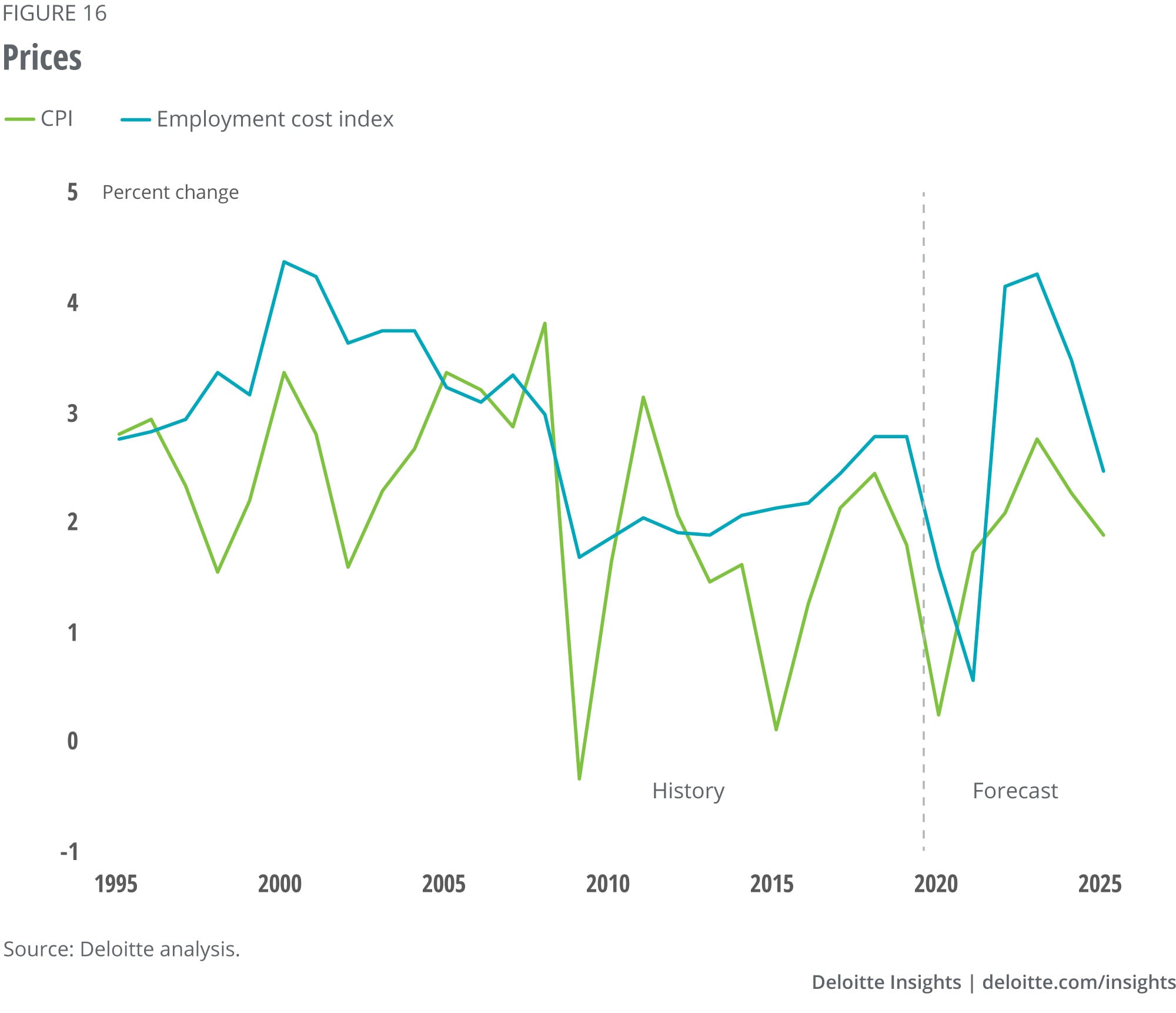

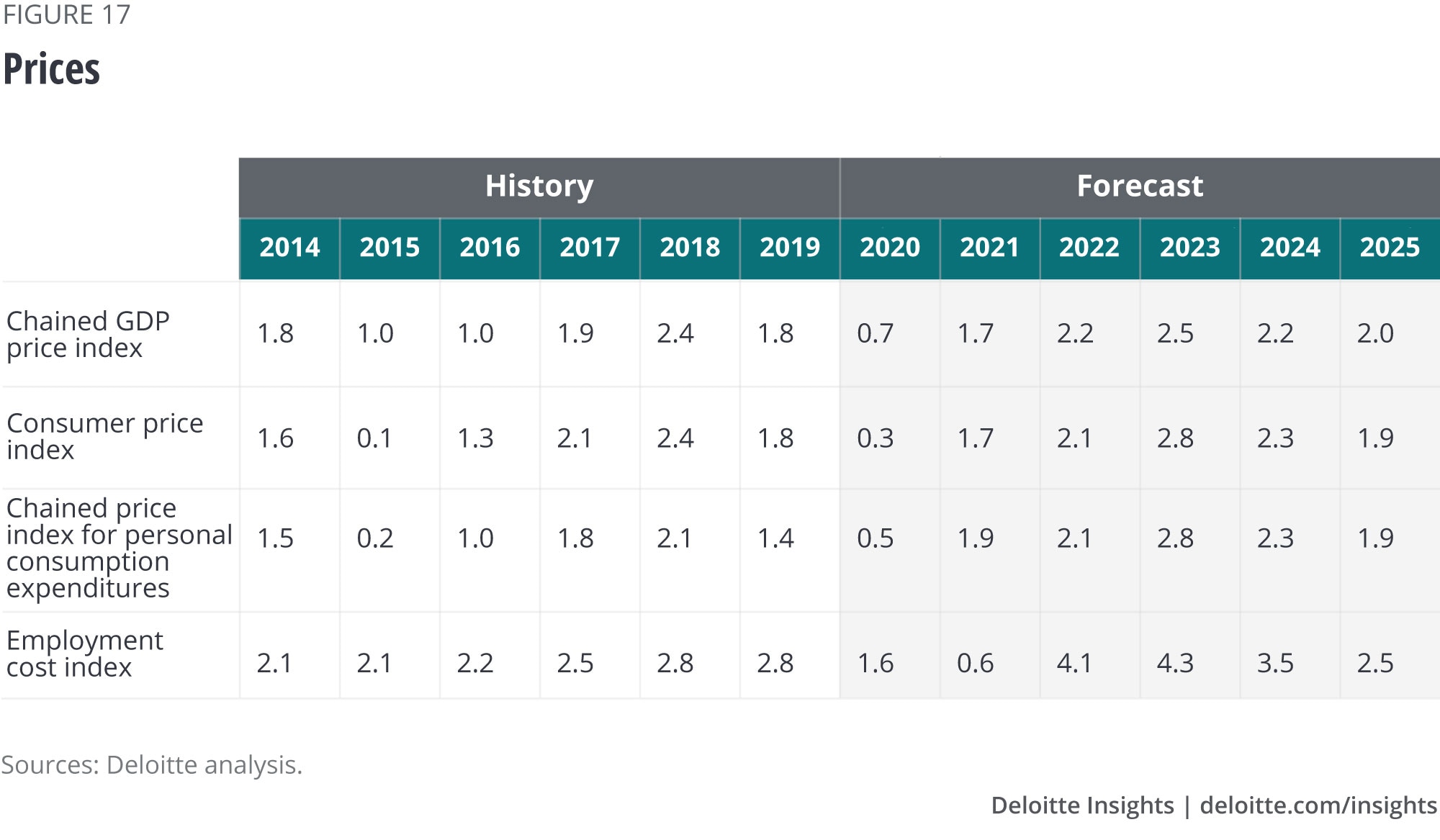

Shutting down much of the US economy to fight COVID-19 might be expected to raise prices, with supply chains strangled. And it might be expected to lower prices, with consumer demand crashing. Which has happened?

The supply shock of the pandemic has clearly raised certain prices. The consumer price index for food at home rose 2.6% in April as supply chain problems caused spot shortages for consumers. That’s a short-term impact, but there are likely to be some significant long-term impacts. For example, requirements for cleaning and social distancing are likely to raise prices of restaurant meals, airplane travel, and schooling (such as day care services) over the next year. Firms in areas such as these will not only be faced with higher costs—they will lose the ability to exploit economies of scale. Added to that, businesses are likely to adopt practices such as larger inventories to reduce their vulnerability to shocks. Those practices will also raise prices—and reduce productivity.

On the other hand, the demand shock has begun to drive down some prices. That’s been most evident in energy, where the consumer price index fell 10.1% in April after dropping 5.8% in March. April consumer gasoline prices fell below US$2 per gallon. That might have made for happy motorists, except that miles driven also fell—in fact, that was a key driver of low gasoline prices. Prices of apparel fell in April, unsurprising given an almost 80% drop in sales. In the baseline forecast, we expect overall demand to remain low, both because of the pandemic and because so many people are out of work. That will likely result in some significant discounting over the next year.

The battle between supply and demand will likely continue through the forecast horizon. In a world of high unemployment, businesses will have little pricing power but will face higher costs. Given these offsetting factors, the baseline forecast calls for inflation to continue at about 2.0% over the forecast horizon.

Appendix

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More on COVID-19

-

The essence of resilient leadership: Business recovery from COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

The heart of resilient leadership: Responding to COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 implications for commercial real estate Article4 years ago

-

Confronting the COVID-19 crisis Podcast4 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the undisruptable CEO Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 potential implications for the banking and capital markets sector Article4 years ago