Four things you need to know about Asia in 2017 has been saved

Four things you need to know about Asia in 2017 Voice of Asia, January 2017

13 January 2017

Are economic forecasts overly gloomy? Notwithstanding protectionist rhetoric, rising global growth looks to trigger an upsurge in trade that would, in turn, fuel stronger growth—and Asia's emerging economies will be direct beneficiaries, bolstered by their own economic reforms.

It’s easy to be gloomy. Global growth has disappointed for some time, and in recent years Asia has started to be part of that problem. The last decade has served up a seemingly never-ending succession of shocks, both political and economic.

Learn More

Voice of Asia is also available via PDF in the following languages:

So we’ve got some positive news for you: Much of the news in 2017 is more likely to be good than bad, with Asia set to be central to better-than-expected global growth this year.

But not all the news is good, so here are our four “need to know” insights for Asia this year:

- First, global growth will surprise on the upside, with Asia—led by India—to be a substantial winner from that. Leading indicators of global growth are on the rise as the big shocks of recent years settle into the rearview mirror, with that good news already bubbling up into a lift in export orders in Asia.

- Second, while growth may be a pleasant surprise, financial stresses are a major risk factor. Global interest rates are finally beginning their long climb back to normal, with the US Fed leading the way. That will generate a lot of volatility in markets, but our analysis suggests Asia is better placed than most to handle that stress.

- Third, the best news within overall global growth will shift back in favour of emerging economies. Even better, this won’t be “lazy” commodity-driven growth. Reforms have boosted the underlying competitiveness of many emerging economies, setting the stage for more broad-based and sustainable, higher-quality growth.

- Finally, the real shock for markets may well be a larger drop in the Chinese yuan. China is juggling some key headwinds, leaving the authorities—in search of a growth booster—with little choice but to go for a much larger devaluation of the yuan.

Insight No. 1: Global growth will accelerate faster than expected, with Asia a big winner

Many forecasters, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, are warning that global growth will moderate, with risks tilted to the downside.

In our opinion, this is overly pessimistic. We see evidence that global growth will accelerate, not decelerate. Leading indicators show this and the underlying drivers of the global economy, such as labour and credit markets, already turning more positive.

And why wouldn’t they? Consider:

- The G3 economies (the United States, Europe, and Japan) are all maintaining or increasing their rates of recovery.

- India continues to surprise by maintaining growth above 7 percent in the face of global headwinds.

- China is stabilising thanks to aggressive policy action to offset that nation’s headwinds.

- Large emerging economies such as Indonesia are poised to accelerate, while others such as Russia and Brazil are set to recover.

- The net benefit of low oil prices is likely to be more evident in 2017. Positives such as higher consumer spending and the expansion of energy-intensive activities will begin to dominate over negatives such as collapsing oil-related capital spending.

Those are powerful positives.

Much of the news in 2017 is more likely to be good than bad, with Asia set to be central to better-than-expected global growth this year.

World trade is rebounding: The early evidence

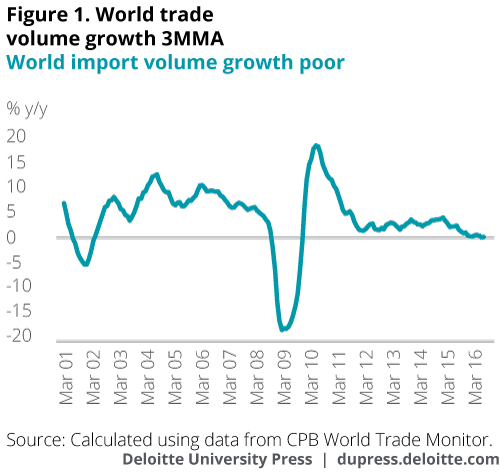

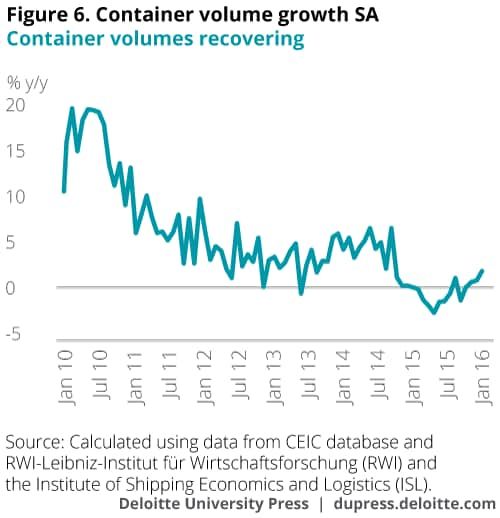

As chart 1 shows, world trade volumes have been in the doldrums for many years.

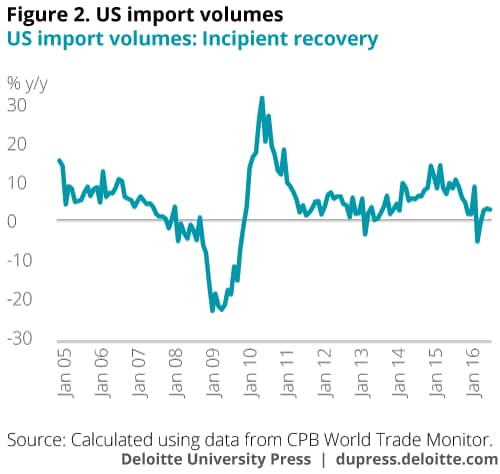

However, as chart 2 highlights, there are very early signs that US import demand is picking up.

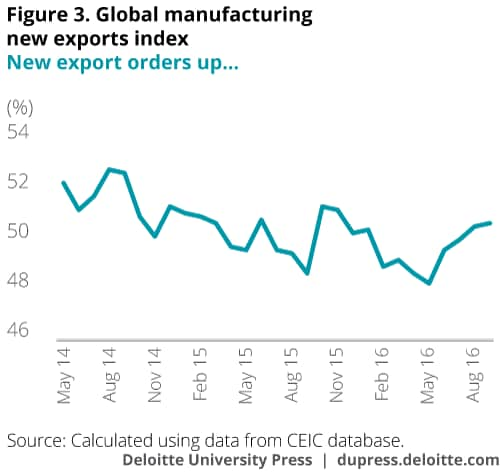

And the leading indicators of world trade show that a gathering rebound is under way:

Trade rebound underpinned by momentum in G3, India, and China

And there’s more good news where that came from:

Other large emerging economies are bouncing back

But wait, there’s more. The OECD lead indicators for Russia and Brazil suggest above trend growth likely over the next 12 months:

The world economy is normalising after successive shocks

This set of good news in many ways has a single source—a lack of new crises.

The world economy is finally coming out of a dark period of successive major shocks. They began with the global financial crisis of 2008–09, but that was then followed by the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis from 2011, a succession of political crises in the Middle East centered around the Arab Spring, the sharp slowdown in Chinese economic growth and the subsequent collapse in commodity prices from 2014, and the ragged performance of large economies following that.

The election of Donald Trump as president of the United States raises some important questions for the global economy in 2017, including in relation to trade. Many of those questions are being asked elsewhere as well, as nationalist and protectionist sentiment proliferates across many developed economies.

However, the outcome may be far less dire than is being feared. As president-elect, Trump has toned down some of his initial campaign rhetoric; more important, there are limits to his influence when swimming against a rising tide of prosperity and globalisation, both of which will continue to provide an important stimulus for trade into the future.

What we are likely to overwhelmingly see through 2017 is the natural healing process that occurs in economies as the worst effects of these shocks wear off. This is forming a base for a more resilient recovery around the world.

The world economy is finally coming out of a dark period of successive major shocks.

The missing ingredient has been capital spending

An acceleration in capital spending in the United States would be big news. Pressed by the need to improve profitability, and as the recovering US economy provides more confidence that domestic risks and external risks such as Brexit and a Chinese slowdown can be contained, capital spending—the missing ingredient in a US recovery—could well revive.

The multiplier effect could be significant in Asia, including in India via increased trade in services. Large US financial institutions are the major consumers of Indian information technology services, and any genuine revival in the United States will lead to better opportunities for service providers.

Of course, this is no sure thing. American firms still face excess capacity and a rising US dollar, which hurts US exports. If business investment does take off, it will be because businesses are confident of a boost to demand and an uptick in inflation—both of which could be spurred by the sort of fiscal stimulus that president-elect Trump has suggested he might champion.

Asian exporters the big winners from global recovery

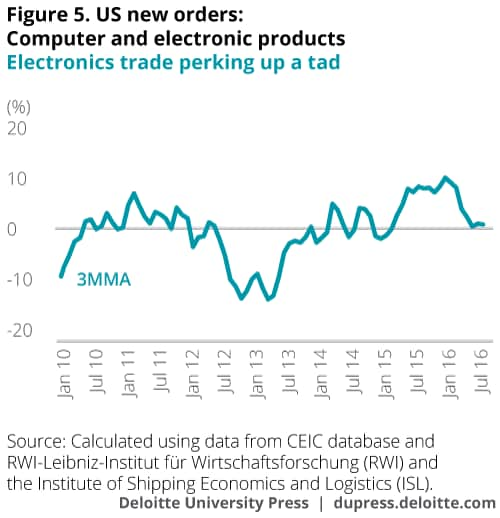

The sub-index for new export orders in purchasing manager indices across Asia are already on the rebound. That’s an encouraging sign, indicating that global demand is slowly but surely gaining strength.

We see the relative winners among Asian economies as those with competitive manufacturing sectors:

- Export-oriented newly industrialised economies will be the biggest winners: Taiwan should benefit given its strong linkages to US technology products—but the strength of its recovery will also depend on how much of a turnaround there is in Chinese demand for Taiwan-made intermediate products. Singapore will be a major beneficiary too, given how trade-dependent that economy is. South Korea will benefit too, particularly if there is a rebound in global capital spending—but the rebound will be constrained by sector-specific challenges in its shipbuilding, shipping, and phone sectors.

- Export-oriented ASEAN economies stand to gain as well: Malaysia has a competitive currency and a strong base of export-oriented manufacturing, and trade is a big share of the Malaysian economy—one of the world’s highest such ratios. Thailand, too, will be a winner, as will Vietnam, although the Philippines and Indonesia are less competitive in export-oriented manufacturing.

- Outsourcing will continue to gain: We also see outsourcing, which has been a major engine of growth for India and the Philippines, strengthening despite the US election-related rhetoric around this topic. India’s outsourcing industry remains dominant in the region, and has morphed into a broader ecosystem integrating voice support along with sales support and software development. Given the advances in the technological domain and the need to maintain profitability, the outsourcing industry is likely to continue showing impressive growth for both India and the Philippines.

- China is an obvious beneficiary from increased demand in the G3, but it is facing more protectionist barriers and some Trump-related question marks; India’s manufacturers remain less geared to a pickup in G3 demand but nonetheless will be positively affected by a recovery in key export markets. Further, India’s manufacturers have considerable potential to sell into newer markets and are already targeting African and Latin American countries.

Insight No. 2: The Fed to raise rates faster than expected, but Asia can handle it

It is clear that the US Federal Reserve is shifting away from its extreme reluctance to normalise interest rates, raising the question of whether the gradient of the rate hike trajectory will be steeper than expected. Some officials are now talking about the risks of not tightening early enough, while the data is pointing to renewed vigor in the US economy:

- There is now a risk that the United States could actually grow too fast and cause some asset markets to become too ebullient.1

- Also, inflation is showing signs of picking up and is heading toward the 2 percent target.

- The surge in Purchasing Managers’ Index activity indicators; the continued, albeit modest, firming of the labour market; and the signs that capital spending—the missing ingredient in the US recovery—may be reviving, suggest the economy is in robust shape. If so, that makes continued ultra-low rates inappropriate.

- And if capital spending really accelerates, as we believe it will, the multiplier effects on the economy will be sizable.

What would higher interest rates mean for Asian markets?

If the US Federal Reserve does lob grenades at global growth in 2017, are the nations of Asia well prepared?

There are several important factors that will determine Asian economies’ resilience in the wake of a Fed rate hike.

Exposure to abrupt withdrawals of external capital: Risky assets such as emerging Asian stock markets and bonds will be re-priced if US interest rates rise and investors become more rigorous in assessing risks.

There are three ways to measure the degree of risk:

- (1) Countries with current account deficits are better off if the deficit is mostly funded by direct investment rather than volatile portfolio capital. Given that, Indonesia remains vulnerable.

- (2) Another measure is the share of a country’s easily sold securities owned by foreigners. That’s an indicator on which Indonesia and Malaysia seem modestly vulnerable.

- (3) A final yardstick is the extent to which short-term debt is covered by foreign reserves. At first glance Hong Kong and Singapore look vulnerable on this score, but that’s only because their large banking sectors exaggerate this ratio. Only Malaysia is moderately at risk here.

Susceptibility to rising interest rates: After a long period of very low interest rates, debt levels have expanded among families and businesses in Asia. Rising rates could hurt those who are over-leveraged. We need to look beyond just debt levels to assess the degree of risk here. If banks are well capitalised and there are few distortions in the economy such as asset bubbles, then the risk is lessened.

Apart from China and Hong Kong, we see little risk of this. The Indian economy has undergone some major changes over the last three years due to active policy action around managing this risk. However, financial markets still remain susceptible to a rise in US policy rates. The recent Fed hike is likely to mean capital moving toward the US markets as investors realign their portfolios. This has historically meant a weakening of currency and volatility in portfolio flows into India.

The bottom line: Resilience in the region has improved as countries have strengthened their economic fundamentals to reduce their susceptibility to global financial volatility. However, with the global economy more interconnected than ever before, no economy is completely insulated, and some are more vulnerable than others.

So although we think that much of Asia will be able to handle the impact of rising US interest rates, it will remain crucial for Asian economies to further improve their resilience.

Resilience in the region has improved as countries have strengthened their economic fundamentals to reduce their susceptibility to global financial volatility.

Insight No. 3: A more competitive Asia roars back with higher-quality growth

Over the past few years, a bunch of factors led to emerging economies underperforming. That list includes political convulsions, unpredictable weather, a weak global economy, falling commodity prices, and the short-term ill effects of reforms such as subsidy cuts and tax reforms.

However, with some of this bad news now dissipating, the large emerging economies are poised to lead global growth into the next decade—all the more so because the quality of their growth is improving. A number of factors are driving this:

- Lazy commodity-driven growth is being reversed: Low commodity prices have weighed on the trade and revenue positions of several emerging economies—a problem for Indonesia in particular. However, we believe that the damage from the commodity boom reversal has been done and commodity-related activity is beginning to see a recovery that could well extend into 2017. Second and more importantly, instead of reverting back to commodity dependence, nations are reinvigorating reform efforts to diversify their respective economies.

- Strong policy action: We are seeing stronger policy responses across the region as well, helping to boost economic growth. Government policies and spending are boosting private-sector confidence and are helping to generate a recovery in investment spending. That will create new capacity and further improve competitiveness.

- Accelerated reforms: These efforts are being complemented by necessary reforms to address the deep-seated structural weaknesses that have held back economic competitiveness and growth across Asia in recent years.

That’s a good news story. Yes, Asia’s growth has faced challenges, but a variety of responses look set to make a helpful contribution to the region’s growth in 2017.

Taking stock of relative competitiveness

Global institutions frequently compare countries across a range of indicators in order to gauge their relative competitiveness and performance over time.

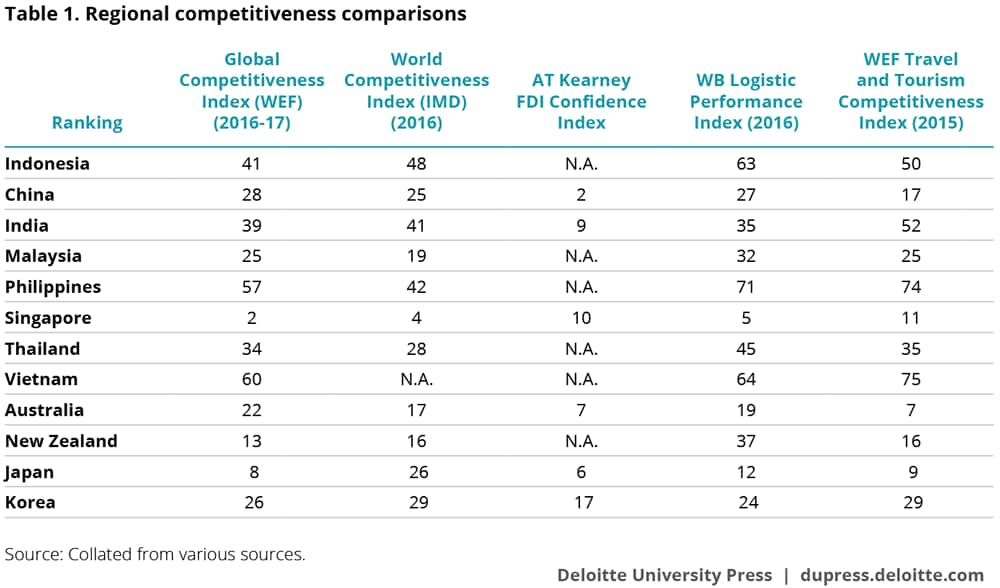

Across most competitiveness indices (see table 1), we see a recurring trend among Asian economies:

- Singapore leads its peers almost across the board

- Malaysia and China fall in the middle

- They are trailed by India, Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam

However, an assessment of competitiveness over time suggests these trailing economies are on a rising curve thanks to the factors mentioned above. We can see this partly by comparing their ranking in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index, which gauges competitiveness by assessing a wide range of key aspects that matter for competitiveness. That index measures competitiveness based on criteria ranging from institutions and the macroeconomic environment to innovation and business sophistication.

India makes the largest gains: India was one of the region’s only two countries that showed an improvement in the World Economic Forum’s competitiveness index in 2016. It rose 16 positions, moving up to rank 39th out of 138 countries. The improved performance was underscored by progress across all sub-components of the competitiveness index, notably so in market efficiency, business sophistication, and innovation. The cumulative reform efforts of the Modi administration are clearly easing the constraints to doing business in India. The last year in particular has seen some key legislations pass, the implementation of which will likely have a noticeable effect on competitiveness in the coming years. In May 2016, the government passed the “Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code 2016,” which will enable insolvency to be settled on a timely basis, create a record of serial defaulters, and allow faster turnaround for businesses in India. Another key reform has been the passage of the “Goods and Services Tax Bill August 2016,” aimed at converting India into a unified market with four indirect tax rates across all states. This is expected to be the biggest game changer in India’s tax regime in recent times and is likely to result in increased competitiveness for Indian producers.

New Zealand has improved quickly, while Australia has lost ground: Australia’s ranking in the World Economic Forum competitiveness index slipped back in 2016–17 to tie its previous worst position of 22nd out of 138 countries. Key drivers of the result were innovation, where Australia continues to slip behind developed economy peers on the World Economic Forum measure, and a relatively high corporate tax rate. In contrast, New Zealand has rocketed up the rankings in recent years, reaching 13th place in 2016–17. That compares to the country’s 25th ranking just five years ago. Although New Zealand also ranks behind other developed economies in terms of innovation, the country was ranked first in 2016–17 for financial market development, time taken to start a business, efficacy of corporate boards, and the strength of investor protection.

Indonesia is improving but remains an economy of contrasts: Indonesia fell five positions in 2016, ranking 41st overall. The macroeconomic environment, financial market development, and innovation have improved markedly, but Indonesia is still languishing in health and basic education, as well as labour market efficiency and technological readiness. However, prospects are better than ever. The Jokowi government has already launched 13 economic policy packages to improve Indonesia’s business environment. When coupled with both the government’s plans to continue improvements in health and education and the increased technology uptake across firms, the new policies will be amplified and translate to higher growth.

The Philippines fell in the rankings for the first time in a decade: With bureaucratic red tape, corruption, and infrastructure bottlenecks hampering competitiveness, the Philippines slipped 10 places in 2016 to rank 57th, the first time in a decade that the nation has fallen in these rankings. Other weaknesses identified included the country’s low goods market efficiency, poor technological readiness, and inadequate infrastructure. Still, with a robust macroeconomic environment and a competent economic team focused on improving these fundamentals, we are likely to see improvements in areas such as infrastructure and eased investment restrictions.

Vietnam displays short-term weakness: Vietnam fell four spots in 2016 to rank 60th, following a climb up the competitiveness ladder since 2012. Vietnam reported poorer performance in the criteria of macroeconomic environment and labour market efficiency, but the long-term outlook is positive. Better infrastructure and education limited the rank slippage. Also, Vietnam is growing into a manufacturing powerhouse, supported by surging foreign direct investment.

The bottom line: As the years of “lazy” commodity-driven growth recede, governments are being forced to undertake reforms that improve long-term fundamentals—and the payoff looks to be just around the corner. With competitiveness already improving, these reforms will produce a surge in Asian competitiveness in coming years that will further boost the region’s growth prospects.

Insight No. 4: The real shocker for Asia: A devaluation of China’s yuan

Financial markets have gotten over their shock at China’s sudden move to weaken its yuan in mid-2015. The Chinese authorities have pursued a strategy of a steady but unpredictable pace of depreciation that currency markets have taken in their stride.

However, chances are that the markets haven’t seen anything yet: Conditions are falling in place for a currency move that might be more unnerving.

China: Buying short-term growth at the expense of longer-term stability

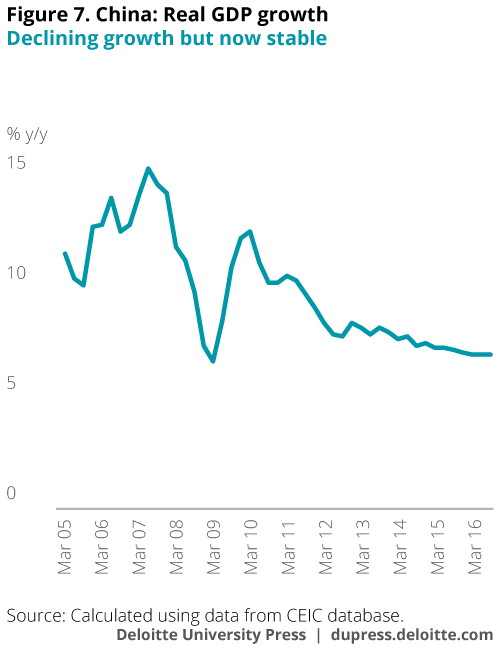

The Chinese economy is back on a relatively stable footing and probably hit its 6.5–7 percent target range for growth in 2016. The recent shocks of the stock market rout, the yuan’s sudden devaluation, and the subsequent flight of capital in 2015 now seem to be behind us. According to the official data, the economy has been growing at a steady annual rate of 6.7 percent (see chart 7).

But China has paid a price for this nascent stabilisation. It has come on the back of aggressive fiscal and monetary stimulus directed by the central government, channeled through local governments and state-owned enterprises and bankrolled by large, government-linked financial institutions. Desiring a cyclical boost to put the economy on firmer ground, policymakers have turned back to their old playbook of debt-fuelled growth, facilitated by monetary easing measures by the People’s Bank of China.

As a result, China’s ratio of total debt to GDP has soared, jumping from around 200 percent in 2010 to just under 300 percent in 2015, with much of the new leverage extended to the corporate sector. In a monetary system with a weak credit culture, this is risky.

Consider the following:

Reaching the limits of the current policy mix

Other challenges limit the effectiveness of China’s traditional mix of fiscal and monetary tools:

- The economic revival has been overly dependent on the buoyant property market, particularly in first-tier and popular second-tier cities where prices have skyrocketed unsustainably. The likes of Beijing and Shenzhen saw their prices lurch upward in 2016. This is being fueled by rampant credit growth that the government is now trying to rein in, fearing the potentially destabilising consequences of a housing bubble.

- And there’s a growing problem: Credit-based stimulus is increasingly less effective in boosting growth. This means that there has been little real economic growth to show for all the liquidity that has been unleashed; this liquidity has increasingly been funneled into speculative areas, creating distortionary bubbles.

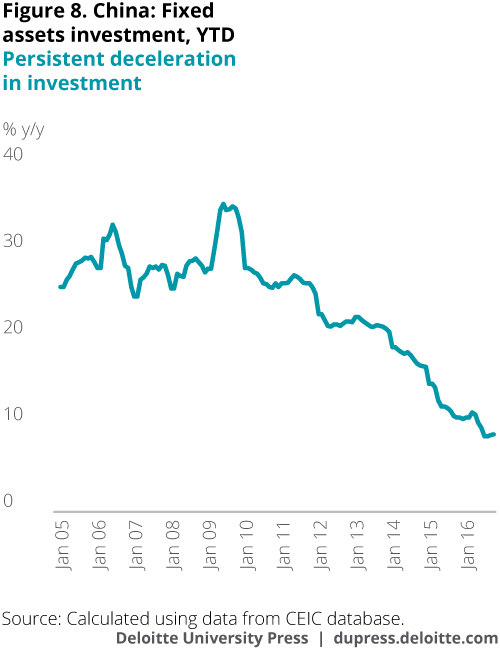

- In addition, the necessary deceleration of fixed asset investment will weigh on growth prospects, given that investment constitutes about 50 percent of the economy. The extra leverage that policymakers have unleashed has simply added even more capacity to an economy already saddled with chronic industrial overcapacity, which will deter private investment.

- Confidence in the long-term outlook remains a scarce commodity. Capital flight from China has ebbed somewhat but continues in various forms, through alternative avenues, reflecting still-sharp concerns about downside credit and growth risks. Businesses and individuals are employing a variety of ways to move cash out of the country. One popular way is through over-invoicing by Chinese companies for imports from Hong Kong. Another way is via the purchase of life insurance products in Hong Kong. Mainland Chinese circumvent capital controls by paying for expensive insurance products and then cashing out of these policies soon after in Hong Kong.

The underlying weaknesses in the Chinese economy mean that capital outflows will likely continue; this may, in turn, put downward pressures on the yuan.

This increasingly leaves policymakers with no choice but to surprise markets with a devaluation

Fiscal policy will likely be stepped up to ensure that China does not fall off its growth trajectory; more government spending on infrastructure and social welfare will likely be announced in the near future.

However, given the headwinds facing private investment (which makes up almost a third of the economy), this alone may not be enough. Policymakers will likely recognise that stimulating domestic demand comes with a heavy price and feel the need for stronger exports to drive economic growth.

At some point, a currency depreciation may be considered necessary; the key question is the magnitude of that depreciation. Given the People’s Bank of China’s tightening of outflows, it is unlikely the yuan will fall more than 5–7 percent against the US dollar.

However, a larger-than-expected depreciation of, say, 10 percent—which cannot be ruled out—would have a disruptive impact on the region. It would certainly cause Asian currencies to depreciate across the board, with manufactured-goods exporters such as Korea, Taiwan, and Malaysia most affected. Such a policy response is perhaps warranted by China, given its challenges of reflating the economy and cutting spare capacity, and might trigger a competitive devaluation by Japan.

Such competitive devaluations could drive the dollar to a level detached from underlying fundamentals, resulting in delays of necessary rate hikes. Indeed, the US dollar is already experiencing considerable upward pressure and could appreciate further if fiscal and monetary policies evolve in line with market expectations. An elevated dollar would mean a cheaper yen (a good thing for Japanese exports), further downward pressure on the yuan, weaker US exports, higher inflationary pressures in Asia, and difficulties for Asian companies with large US dollar-denominated debts. Such a scenario would present problems for many Asian economies yet also provide some opportunities.

However, one thing is clear: It is becoming less realistic to expect China to repeat its pledges of strong economic growth and a stable currency in order to ensure regional stability, as was the case during the Asian financial crisis. In the long run, most Asian economies will benefit from China’s successful rebalancing of its economy.

Conclusion: Let’s finish where we started

There has been plenty of doom and gloom. The political and economic shocks of the last decade have, no question, contributed to slower growth and undercut confidence.

But the doom and gloom is overdone. Much of the news in 2017 is more likely to be good than bad, and Asia is well placed to play an important role in driving better-than-expected global growth this year.