Loving the one you’re with has been saved

Loving the one you’re with How behavioral factors influence responses to customer rewards and incentives

18 June 2016

Thanking customers as a way to kindle loyalty seems straightforward enough. It’s not. Learn how behavioral biases can affect outcomes.

Challenge: Reinforcing good behavior

“The first year I started purchasing from them, they sent me a plastic coffee mug during the holiday season. A year later, they sent me a stainless steel mug. I wondered if that meant I had been a better customer that year, or maybe they just decided to upgrade their mugs. Since then, I haven’t received anything. I am not sure whether they stopped sending out mugs or I was no longer one of their better customers.”

Winning customers’ hearts and minds—or more specifically, wallets, good feelings, and positive word of mouth—is a perennial top-of-mind business issue across sectors. But many firms struggle with how best to thank their customers, not only in terms of the amount of resources they should devote, but also the most effective way to acknowledge this good behavior. While saying thank you as a way of kindling loyalty seems straightforward enough, research suggests otherwise. People are actually quite sensitive to exactly how an organization acknowledges their good behavior, and the field of behavioral economics teaches us that a number of cognitive biases weigh heavily on perceptions (see sidebar, “A Deloitte series on behavioral economics and management”).

Winning customers’ hearts and minds—or more specifically, wallets, good feelings, and positive word of mouth—is a perennial top-of-mind business issue across sectors. But many firms struggle with how best to thank their customers, not only in terms of the amount of resources they should devote, but also the most effective way to acknowledge this good behavior. While saying thank you as a way of kindling loyalty seems straightforward enough, research suggests otherwise. People are actually quite sensitive to exactly how an organization acknowledges their good behavior, and the field of behavioral economics teaches us that a number of cognitive biases weigh heavily on perceptions (see sidebar, “A Deloitte series on behavioral economics and management”).

It’s worth noting that overall, appreciation has been an underutilized measure of today’s consumer’s loyalty. While the majority of loyalty research has focused on satisfaction and willingness to recommend, the role that customer acknowledgment (appreciation) plays in both customer satisfaction and repurchase behavior has only recently started to receive attention as a driver of both customer behavior and choice.1 This link between appreciation (acknowledgment) and repurchasing deserves further exploration. The research presented in this article suggests that:

- A simple “thank you” may do more on its own than when coupled with a small financial reward.

- The timing of an acknowledgment may be more important than the frequency.

- These “thank you’s” are not considered in isolation; rather, people compare past “thank you’s” to the most recent.

Our prior work in this space has looked at consumer-imposed reasons for remaining in sub-optimal business relationships.2This article explores the other side of the coin: What can organizations do to encourage customers to become and remain “holistically” loyal patrons—that is, present in both body (behavior) and mind (attitude)? Drawing from recent research, we provide insights and recommendations regarding reward types, amounts, and timing, as well as the importance of ensuring that these rewards offered are sustainable over time.

A Deloitte series on behavioral economics and management

Behavioral economics is the examination of how psychological, social, and emotional factors often conflict with and override economic incentives when individuals or groups make decisions. This article is part of a series that examines the influence and consequences of behavioral principles on the choices people make related to their work. Collectively, these articles, interviews, and reports illustrate how understanding biases and cognitive limitations is a first step to developing countermeasures that limit their impact on an organization. For more information visit http://dupress.com/collection/behavioral-insights/.

Thanking customers: The power of incentives

In his groundbreaking work, Psychologist B.F. Skinner demonstrated just how powerful reinforcements can be when seeking to influence behavior. He conditioned pigeons to perform atypical and difficult tasks, such as playing ping-pong and dancing, by systematically rewarding them for desired behaviors and negatively reinforcing undesired behaviors.3

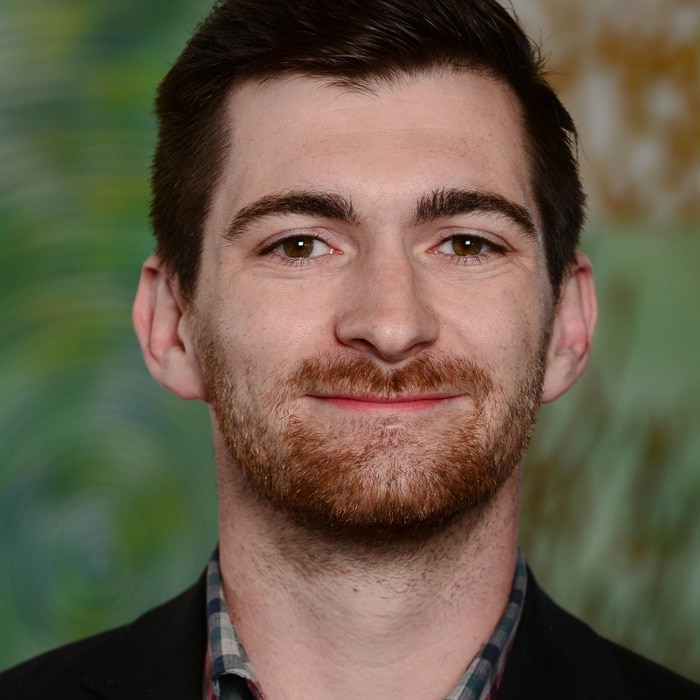

Skinner identified a number of contingencies that should be considered when using incentives to elicit behaviors. Of particular relevance are the following three considerations, explained in figure 1, which we refer to as the three pillars of thanking customers: 1) The type and amount of acknowledgment (the “how”); 2) The timing (and frequency) of acknowledgment (the “when”); and 3) The sustainability and frequency of the acknowledgment (the “how long”).

Setting the stage and bar

You had me at “hello espresso.” For years, the highlight of my morning was my visit to the coffee shop. It was the perfect experience: the smiling barista, who quickly knew my order without me having to state it, a handwritten “thank you” note inscribed on my cup with silver Sharpie, and a vibrant community. As a loyal customer, every couple of weeks, I earned a free drink. I loved it.

However, the rewards program that I came to love has ceased to exist. With the new program, it seems like my social security will kick in before I see my next reward. When did I become just another line on their spreadsheet? Suddenly, the barista doesn’t seem as warm as he scribbles a tacky “thank you” on my paper cup. The crowd has changed as well—more just faceless strangers these days. Have they changed their espresso beans, too? It just doesn’t taste the same. Maybe tomorrow I’ll just settle for the instant coffee at work. At least I’ll shave off 10 minutes on my commute and save a few bucks.

As our opening vignette, along with the one above, suggests once any reward is introduced, customers feel at best confused, and at worst betrayed, if it is subsequently taken away from them. Professor Michael Lewis explains that in the customer’s mind, the mere presence of a reward program can create a perceived contractual relationship with the company. Customers believe if they hold up their part of the deal, the company must do the same, a behavioral bias called the norm of reciprocity.4Thus, once a reward is entered into the equation, a customer then feels entitled to it.

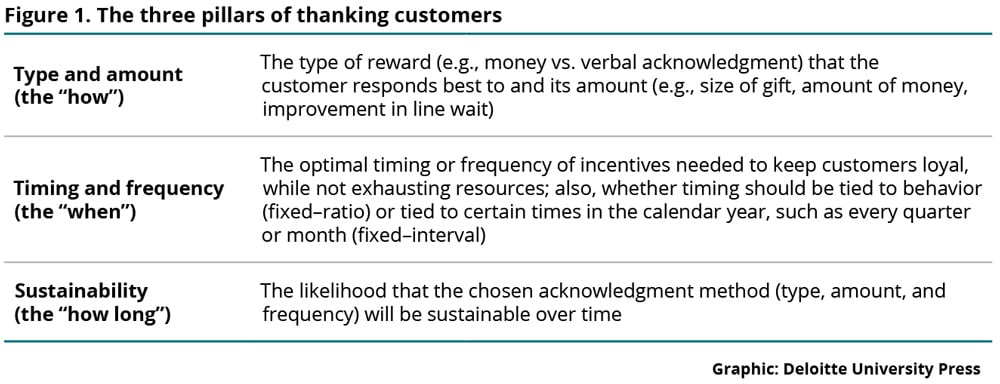

The behavioral factor underlying the decreased satisfaction that occurs when the reward is removed from the equation can best be explained by the expectancy disconfirmation model.5As figure 2 illustrates, our satisfaction with a product or service offering is not driven by the performance of the offering itself, but rather by the gap between our expectation of the experience and the actual performance of the product offering.6Thus, our satisfaction is not made in isolation, but is based on the expectation that has been set for us, which is primarily driven by past experiences and firm communications. Not only can satisfaction decrease when an expected reward is taken away, another cognitive bias, loss aversion can also come into play, which suggests that the pain felt from having something taken away from us is greater than the gain felt from that same item being given to us.7 Consequently, firms need to err on the conservative side as they think about the type, degree, and frequency of the rewards they offer customers as a means of acknowledgment.

How to thank: Can’t buy me love

With regard to how best to thank customers, financial incentives remain a common way for firms to demo nstrate their appreciation to existing customers for their loyalty. However, recent research suggests that these financial incentives can backfire. This is particularly true if incentives are introduced too early or when they fall under the threshold of what the customer considers to be an appropriate amount.

nstrate their appreciation to existing customers for their loyalty. However, recent research suggests that these financial incentives can backfire. This is particularly true if incentives are introduced too early or when they fall under the threshold of what the customer considers to be an appropriate amount.

Once money is introduced into the picture, it will always remain part of the conversation

One recent stream of research found that how we reward customers early on in the relationship has implications for the relationship moving forward. Specifically, if you fall into the trap of showing customer appreciation through price discounts in the early stages of the relationship, customers will then expect higher discounts as the relationship continues, a phenomenon known as the loyalty–discount cycle.8 A behavioral bias that may explain this phenomenon is the crowding out effect,9which suggests that once financial benefits are brought into a business transaction, they will override the inherent benefits derived from a product or service.

Thanking with money is clearly a slippery slope.... Companies should consider finding nonfinancial ways to thank customers in the early stages of the relationship, as this sets expectations moving forward.

Given these biases, thanking with money is clearly a slippery slope. Therefore, companies should consider finding nonfinancial ways to thank customers in the early stages of the relationship, as this sets expectations moving forward. These can include training sales associates to build personal relationships and identify and anticipate customer needs, just as our barista in the vignette did. Tactics like these increase loyalty because customers believe they are receiving special treatment, which is one of the primary reasons why consumers remain in existing business relationships.10

How monetary acknowledgments can backfire

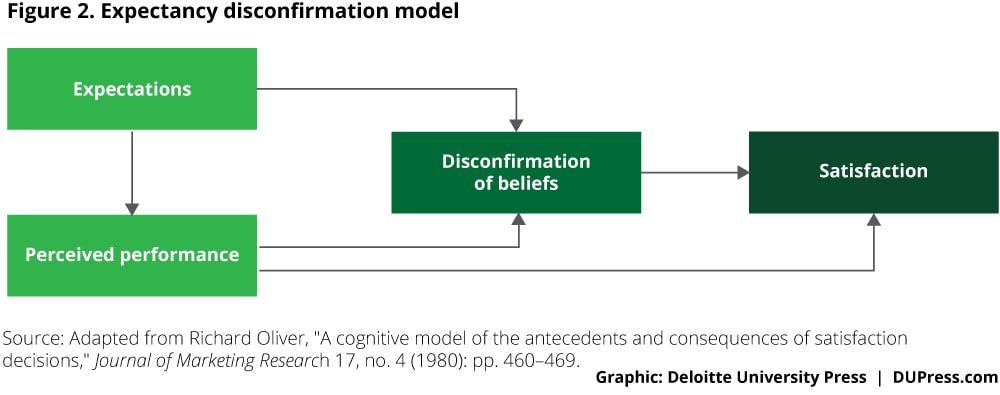

In addition to the negative long-term implications outlined above, additional recent research found that financial incentives that fall under a certain threshold can immediately undermine basic communication efforts to thank customers. Specifically, in an effort to understand the effect a small financial incentive included with an acknowledgment had on customers, researchers looked at the responses to acknowledgments of hotel guests and college campus dining patrons.The hotel guests were asked to write a review of their stay, while the dining patrons were asked to complete a dining establishment review. In both cases, the participants were divided into two groups: One group received a written acknowledgment thanking them for their time and feedback, while the second group received the same note but they were also promised a nickel to thank them for their assistance. Respondents were then asked to indicate the degree to which they felt appreciated. As figure 3 illustrates, respondents who received the small financial benefit with their thank you felt significantly less appreciated than did participants who received a verbal acknowledgment alone, a phenomenon known as the trivialization effect.11

This finding is consistent with recent behavioral economics research outlining how individuals keep two sets of norms, or expectations, regarding patterns of behavior and how the world should work. Social norms include simple requests that people make of one another and subsequent acknowledgments of thanks. Market norms, meanwhile, include fair exchanges and an expectation of comparable benefits for efforts exerted.12 It has been well-established that people live concurrently in these two worlds.13

How market norms affect loyalty

In an effort to confirm that the reason feelings of appreciation eroded was due to the inclusion of the small financial benefit (nickel) amount, the researchers conducted a follow-up experiment.Here, they asked participants to imagine that they frequently go shopping at a mid-priced clothing store and bring the store a lot of business by encouraging others to shop there, and writing social media reviews about the store and its products.

Participants were then presented with one of nine email thank-you responses with varying discount offers, ranging from no discount to 40 percent off their next purchase.14Similar to the previous study, after receiving the email, participants were asked to rate how appreciated they felt. The results suggest that including a financial benefit can be fine, as long as it is not too small. Specifically, the retailer benefited from this incentive only when the discount reached 15 percent. This indicates that firms may benefit from providing some sort of financial perk, as long as it isn’t below market expectations.

Mitigating the trivialization effect

Given what we know about how tricky it can be to use financial incentives to win loyalty, practitioners are wise to consider how to provide the right amount of financial incentives, which are sustainable over time, without “giving away the store.” Factors such as the existing customer experience within the product category, the prevailing market environment, and competitors’ discounts may dictate what an appropriate offer might be. However, there may exist opportunities for firms to leverage anchoring points when setting financial benefit levels. Anchoring refers to individuals’ tendency to rely on initial, recently presented, or salient information to guide future decisions or expectations.15

With this behavioral tendency in mind, researchers tested how a 5 percent discount on a purchase, included with a verbal acknowledgment was received when it was provided alone versus offers in which their discount was highlighted within a list of other smaller discounts (for example, 1 percent, 2 percent, 3 percent, and 4 percent).16 As the anchoring cognitive bias predicts, when consumers were privy to these additional lower potential discounts, their level of felt appreciation increased by almost 20 percent vs. when they received the 5 percent discount with the acknowledgment. Still, it is worth noting that this felt appreciation level did not surpass the average appreciation felt from a verbal acknowledgment alone.

Another study looked at whether giving a small financial donation to a charity on the customer’s behalf would be a better strategy.17 While the study found that giving a small amount to a charity instead of the participant does mitigate the trivialization effect, there was no significant difference between appreciation felt using this tactic vs. offering a verbal acknowledgment alone. It is possible, though, that charitable donations made on a customer’s behalf may create a balance between the trivial and market expectations for financial acknowledgments. Consider this: Cash-back incentives for a new automobile purchase rarely dip below $500.18 Despite this, Subaru has completed its eighth year of donating $250 for every new vehicle sold or leased on behalf of the purchaser throughout the holiday season.19 Based upon the behavioral research, it would seem that $250 may not be enough of a market-level incentive. But given the popularity of this program, customers may respond favorably to appropriate pro-social acknowledgments, even if they fall below market value.

If in doubt, leave the financial acknowledgment out

Taken together, these studies suggest that financial acknowledgment can do more harm than good if the incentive amount is not gauged properly (for example, unless the amounts are well above established market expectations). Beyond exhausting company resources, these financial acknowledgments have the potential to undermine efforts to show appreciation. Companies with resource constraints that wish to reward customers financially may choose to give a small amount to charity, ideally of the customers’ choosing. In the end, though, a simple expression of thanks may be more favorably received and less risky than offering a financial reward.

When to thank: Timing is everything

Our final consideration deals with how often and when a firm should show their appreciation. It turns out that timing can be everything. Research shows, in fact, that the timing of an acknowledgment can sometimes be more important than the actual form of that acknowledgement. For the acknowledgment to be effective, the research we reviewed suggests that it needs to be viewed as a response—or reaction—to the desired behavior.20

When any response is better than no response

Through a series of experiments, researchers concluded that any reaction (response) is better than no reaction, as long as it is viewed as contingent upon (or a reaction to) the individual’s behavior. People like to repeat behaviors that generate reactions, even if the reactions are negative or not useful; the mere presence of a reaction makes the corresponding behavior more engaging. This phenomenon is known as the mere-reaction effect, and beneath it lies an important cognitive bias, the illusion of control.21Humans routinely demonstrate a desire to have control over their environment, and to exercise control where opportunities to do so exist.22 In essence, to seek a reaction is to seek information about one’s power in controlling something. The information value is in the presence of the response itself vs. the content of the response.

Through a series of experiments, researchers concluded that any reaction (response) is better than no reaction, as long as it is viewed as contingent upon (or a reaction to) the individual’s behavior. People like to repeat behaviors that generate reactions, even if the reactions are negative or not useful; the mere presence of a reaction makes the corresponding behavior more engaging. This phenomenon is known as the mere-reaction effect, and beneath it lies an important cognitive bias, the illusion of control.21Humans routinely demonstrate a desire to have control over their environment, and to exercise control where opportunities to do so exist.22 In essence, to seek a reaction is to seek information about one’s power in controlling something. The information value is in the presence of the response itself vs. the content of the response.

People like to repeat behaviors that generate reactions, even if the reactions are negative or not useful.

One simple study illustrating this point was a bean-throwing experiment. Here, participants were placed five feet in front of a target, with a bucket of soybeans at their feet and then asked to spend three minutes throwing soybeans, one at a time, at the target. They were also told they could repeat the task as many or as few times as they wished during the three-minute period. Participants were assigned to one of two conditions: one in which the target was made of metal, and would emit a sound when hit by the bean, and the other, where the target was made of sponge, and gave off little to no sound when hit. In a pre-test, the sound was rated as slightly negative.23 On average, the participants assigned to pitch soybeans at the metal target (the “sound” condition) threw 36 percent more beans during the five minutes than those in the “no sound” condition. There was no significant difference in hit rate (72 percent vs. 70 percent).

This finding was replicated in a “pay what you want” experiment, where each participant was given two dollars: a one-dollar bill and 10 dimes, along with a pen with a retail value of $1.50. Participants were told that they could pay what they wanted for the pen by dropping the money in a payment box, which had a narrow opening at the top to insert coins. Attached to the box was a sign that read: “Pay what you want/use dimes only! Drop one dime at a time!” There were two payment box conditions: one from which sound was elicited with each dime dropped, and one that remained silent with the dropping of the dime. In an effort to control for any social desirability associated with the amount given, the researchers left the room, leaving the participant alone in the room to make their payment. Among those who paid, the participants whose payment box had sound, on average, gave 80 percent more than those whose box had no sound.

Contingency vs. frequency

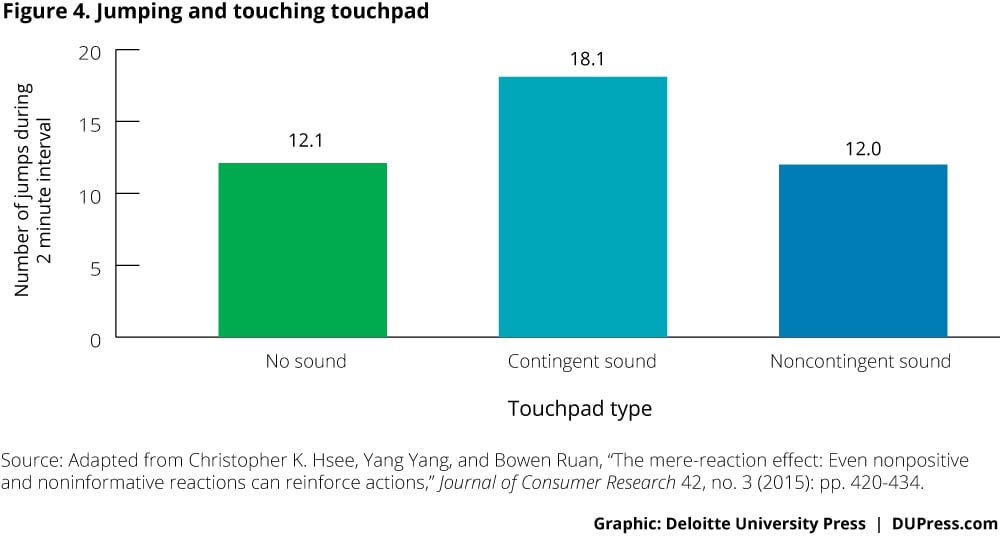

To tease apart whether the increase in desired behavior was due to the sound itself or the fact that the sound was in response to the participant’s action, these same researchers conducted a study in which participants were asked to jump up and touch a touch pad repeatedly for two minutes. Participants were assigned to one of three touchpad conditions: no sound when touched, a contingent sound in which a sound was emitted once touched, and a noncontingent sound condition in which the touchpad emitted a sound randomly (not tied to the jumps) 15 times over the two minutes. As the results provided in figure 4 indicate, those in the contingent sound group jumped and touched the touchpad 50 percent more times than those in the noncontingent sound group. Not only did those in the contingent sound group, on average, jump more than those in the noncontingent sound group, the noncontingent sound group only jumped, on average, the same amount as those in the no-sound group.

The researchers concluded that the repeated behavior was due to the contingent (or reactive) nature of the sound, not just the presence of the sound itself. Given that the noncontingent sound group was, on average, exposed to the sound as much or more than the contingent sound group, it seems that it is not so much the presence of the sound, it is the timing of it that matters. The research conclusions imply that the timing of a reward should be tied to the desired behavior as opposed to coming at a random or arbitrary time (for example, annually). For practitioners setting up reinforcement schedules, this suggests that tying the timing of rewards to desired behaviors is more important than the number of rewards provided. It also suggests that fixed-ratio reward systems (timing rewards to immediately follow desired consumer behaviors) may be more likely to bring success in encouraging repeat behavior, compared with fixed-interval systems (having the reward occur at a set date).

Managerial implications: Sustaining healthy customer relationships

1. Don’t diminish the importance of the post-purchase experience.

So much emphasis is placed on providing customers with a positive customer experience.But what about after? Today, customers have more power after the purchase than ever before, not only in the form of repeat business (behavioral loyalty), but also word of mouth, reviews on social media, and returns.24 How you acknowledge and treat customers after receiving their business is important for both attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty. Cultivating a superior post-purchase experience is a key strategy to inspire customers to keep coming back for more.

2. How to say thanks: When in doubt, leave money out.

Practitioners should err on the side of caution when rewarding customers with money, both in the short term and long term. Small financial incentives can do more damage than good, generating a less positive feeling of appreciation than that formed from the mere offering of a genuine thank you without a financial incentive. Leading with money in the relationship can also set the stage for an unhealthy relationship moving forward. Too much can crowd out the intrinsic value of the product and also set an (often unrealistic) expectation that the discount will always be there.

If a financial reward is deemed necessary, consider giving to a charity vs. the customer—preferably a charity of the consumers’ choosing. There may also be other pro-social benefits associated with this alternative.25 Additionally, take time to understand what your customers deem as appropriate incentive amounts by analyzing the market environment and soliciting customer input. In situations where customers are new to the product category or there is no market norm for financial incentive expectations, there may be opportunities to influence these expectations through anchoring and reference points.

3. Timing trumps frequency: Ensure your response is tied to desired behavior.

Customers want to be acknowledged for their actions. People like reactions and like to repeat behaviors that generate reactions. The research presented here suggests that any response is better than no response—however, the response must be perceived as a reaction to their desired behavior or effort. It is not just a matter of increasing frequency of responses. Practitioners might consider thinking more about responsiveness to consumer behaviors than to overall frequency of rewards.

Marketing implications related to this finding include the timing of monthly newsletters, mailings, and events. To encourage repeat behavior by consumers, be sure to tie reinforcement to individual behavior and minimize adherence to a set calendar reinforcement schedule. Work with the customer’s preferred timing as opposed to trying to dictate a schedule.

4. Be conservative when launching an acknowledgment program.

When launching a new acknowledgement program, take a long view. Know that at all costs, you want to avoid eventually having to pull back and give customers less. So be sure to crawl before you walk. Start off conservatively in terms of acknowledgment type, size, and frequency.Over time, once the program’s participation level and the sustainability of resources are better known, you can consider increasing the size of the offering and or the frequency. Aim to start small, and build it slowly.

Cognitive biases to keep in mind when developing customer acknowledgment strategies

Figure 5 below synthesizes the relevant cognitive biases to keep in mind as you develop your customer acknowledgment strategies.