Frozen has been saved

Frozen Using behavioral design to overcome decision-making paralysis

Too often, many consumers get stuck before making a choice—and then they do nothing. Why does this happen? Learn ways organizations can leverage behavioral economics lessons to help consumers commit to new actions.

It’s a behavior that most companies and policy makers know too well: Often consumers—even loyal ones—don’t follow through on making purchases or taking action, like choosing a health care plan. Something happens along the way, even when the end result of making a choice would clearly be in their best interest. So what altered their decision making? And why? And what can companies do to reengage these consumers?

Learn More

Subscribe to receive insights on Behavioral Economics and Management

Explore the interactive

View the full collection

In the quest to prompt action, companies are embracing the field of behavioral design to craft solutions that take into account how people actually think and behave, rather than how they logically should behave. By combining behavioral economics principles with customer-centered insights, companies can more effectively address and design for a variety of behavioral challenges (see the sidebar, “A Deloitte series on behavioral economics and management”). Consider these two examples:

Who wants to buy a car … during the Great Recession? The economy in the fall of 2008 was in a downturn, and consumer fears of job loss prompted a severe slowdown in auto sales. To help address the economic environment, Hyundai introduced the Assurance program, an innovative buy-back program that promised any car buyer who lost his job could return the car, with Hyundai Capital America assuming the difference in purchase price. While only 350 people took advantage of the offer over the life of the program,1 by reducing consumers’ uncertainty and emotional barriers to action, Hyundai converted job loss anxiety into car purchases. It sold 435,000 vehicles in 2009—an 8 percent increase, when most other automakers were posting sharp declines—in part by removing the fear of job loss from the equation.2

Are you saving enough? Launched in 1998, Allianz’s Save More Tomorrow (SMarT) program was designed to help people more easily save for retirement. Grounded in an opt-out option that required participants to actively dis-enroll, SMarT provided a manageable set of fund options. Rather than reducing current take-home pay, the program incorporated annual increases automatically generated from employees’ yearly raises, rendering them nearly imperceptible. In its first three and a half years, SMarT boosted average savings rates more than 350 percent, and of the 78 percent of participants who joined initially, 98 percent remained through two pay raises.3

Whether increasing car sales or personal savings, issues like these—and many others like them—require organizations to successfully solve for two distinct dimensions of the same behavioral problem: helping consumers overcome decision-making paralysis and commit to new actions. As the examples above demonstrate, companies that deliberately design solutions that overcome consumers’ inertia and indecisiveness can get more new customers in the door, grow their base by increasing consumption, and, consequently, move the needle on their bottom lines.

So what keeps consumers stuck in the status quo and paralyzed by the prospect of embracing change? Specifically, three common hurdles emerge: Consumers freeze when too many choices are presented, they strongly prefer present payoffs to future rewards, and, when presented with an important choice, they are often overcome by fears of failure.

While many of the examples covered are specific to consumers saving for retirement, the principles gleaned from solutions to this classic financial services quandary apply in many other situations as well. Learning from these examples can help companies better identify causes of paralysis and address them in their own industries.

This article will offer a behavioral-design inspired model that practitioners can leverage to help consumers overcome their decision-making paralysis: addressing consumers’ mind-sets in defining options, their perceived ability to make both confident and smart choices, and finally, ways in which they can be prompted to take action.

A Deloitte series on behavioral economics and management

Behavioral economics is the examination of how psychological, social, and emotional factors often conflict with and override economic incentives when individuals or groups make decisions. This article is part of a series that examines the influence and consequences of behavioral principles on the choices people make related to their work. Collectively, these articles, interviews, and reports illustrate how understanding biases and cognitive limitations is a first step to developing countermeasures that limit their impact on an organization. For more information visit http://dupress.com/collection/behavioral-insights/.

What causes consumer paralysis?

Let’s first explore why people get stuck in the first place: What contributes to choosing the path of inaction over that of action? There are multiple causes: an overwhelming number of options with no clear way to gauge which is best; the tension inherent in being forced to make a choice now, despite an uncertain future payoff; and fears associated with the idea of choosing poorly. Each of these symptoms can occur individually or in combination, and certain cues can signal situations that have a high likelihood of potential consumer inaction.

Analysis paralysis: “There are too many options, I just can’t decide.”

Decision paralysis brought on by the inability to choose between options is typically the result of cognitive overload and fatigue. The human brain simply isn’t designed to process and compare the sheer amount of information it is often given. While consumers say they want choices, the need to select between endless options can become a cognitive burden rather than a delight. Without ways to mentally manage or weigh the value of information, people struggle to decide and freeze.4

In his book, Paradox of Choice, Barry Schwartz explained how the proliferation of choice overwhelms consumers’ ability to process information, preventing them from making smart decisions. Similarly, Columbia Business School Professor Sheena Iyengar's jam experiment5—in which shoppers were offered either 6 or 24 varieties of jam for purchase—revealed that more choice actually resulted in fewer sales by a ratio of nearly 8 to 1, as potential purchasers struggled to weigh one option against another and bought nothing. This state of choice overload tends to reduce consumers’ confidence in a decision they have made, and can prevent making one at all.

Buying jam is one thing . . . but a similar tendency has been shown to occur when people are choosing a retirement plan.6 Research shows that an inverse correlation exists between the number of plans offered and the likelihood of signing up. A 2001 study indicated nearly a 20 percent decline in participation between plans offering two funds and those offering 59 options,7 despite the common perception that the presence of more choices enables a “just for me” fit. The cognitive work required to parse and compare large amounts of information quickly spirals into confusion that diminishes consumers’ ability to choose,8 even when people fully recognize the importance of saving for retirement early.

Facing the uncertainty of the future: “I know I should . . . but that can wait.”

In addition to the mental exhaustion caused by juggling multiple complex options, saving for retirement faces a second challenge that encourages paralysis: Outcomes set in the distant future typically lack a sense of urgency in contrast with everyday needs, making it easy to defer decision making to a tomorrow that never arrives. The human tendency to overinflate the here and now, known as the present bias, makes us regularly tip the balance in favor of choices that benefit us in the short term.9

This form of paralysis arises from conflicting values between peoples’ present and future selves, in which “the now” is concrete, but the future is uncertain and difficult to plan for. In the context of long-term planning, today’s consumer has well-defined preferences but little sense of—or even empathy for—what her 80-year old self will need or want.10 Not surprisingly, then, situations in which people face major decisions that have uncertain downstream implications, like saving for retirement, are ripe for paralysis.11

Today’s consumer has well-defined preferences but little sense of—or even empathy for—what her 80-year old self will need or want.

This uncertainty about the future is compounded when people have little exposure to or practice with making a decision. Cognitive research has shown that people often learn and make decisions using “case-based reasoning”—solving problems by recalling previous situations and reusing that information as fodder.12 With no personal experience, feedback, or a memory of past reference points, consumers feel ill-equipped to make the right call; even after gathering additional information to supplement their view, they are often left with the sneaking suspicion that important “unknown unknowns” remain.13 The behavioral tendency to explicitly or implicitly lean on anchors—trusted reference points—provides our brains with a place to start understanding what good looks like. Without these anchors, and with only tenuous confidence in their own ability to choose wisely, consumers stall and do nothing—sometimes indefinitely—rather than commit to the wrong option.

The process of choosing retirement plans, with its mind-boggling range of funds and investment options, is rife with this form of uncertainty but hardly the only instance. For example, newly eligible Medicare consumers, who don’t yet fully understand the complexities of this system, often put off plan selection. Their worry about choosing a Medicare plan, borne partly out of concerns about choosing the wrong kind of coverage for their needs, is heightened due to their inexperience with the product itself. Lacking confidence that any choice is the right one, they procrastinate.14

The impact of emotion on behavior: “I worry about failure, and I hate feeling dumb.”

Consumers also hesitate when they fear or worry about the possibility of making a bad decision. Given the high levels of risk or uncertainty involved, consumers find retirement planning to be unpleasant, and are often fraught with anxiety rather than focused on the anticipatory pleasure of the unknown. This, coupled with the fact that people tend to avoid what makes them nervous, explains why they put off even thinking about funding their post-employment years.

Another key behavioral principle, loss aversion—which states that people hate to lose far more than they enjoy winning—is a factor in this kind of situation. Even consumers who do manage to overcome their aversion to dealing with stressful decision making worry about making a bad choice: They hate the idea of being forced to live with a sub-par option, but, just as important, they worry about looking silly or stupid for having chosen poorly. In this case, the potential loss of a best-possible future due to bad choice making is compounded by the potential personal humiliation of being responsible for having made the bad decision. Collectively, these negative emotions supply a powerful motive for doing nothing.15

Even the projected distaste of having to settle for “good enough” can indefinitely suspend decision making. Consider consumers and mortgages. While consumers are well aware of the fact that mortgage rates today are at historical lows, many find it impossibly tempting to wait and see if rates drop from 4.25 percent to 3.75 percent. Unable to let go of the possibility of a slight reduction, consumers sit and wait for an objectively excellent rate to inch further down. Like long-term investing, with consumers’ constant fear of buying funds either too soon or too late, it’s easy to get lost in “what might have been” rather than actual savings.

Finally, anxiety-related paralysis can be heightened when consumers are in control of decisions but lack confidence in making them. While having control over important choices seems like a benefit, the responsibility of making a smart decision amplifies the pressure of choosing well. Choosing one retirement fund or Medicare plan also means forgoing other options, and consumers’ sense of “might have been” reinforces their distrust in their own judgment and competence.16

Taking action: Getting past paralysis

To counter the biases outlined above, companies should design for three key moments in which people are vulnerable to paralysis: harnessing consumers’ incoming preconceptions—or their mind-sets—about what to do; reinforcing their perceived ability to select and follow through on a good decision; and “unfreezing” consumers to take action (see sidebar, “Understanding consumers’ decision-making arc”).

Understanding consumers’ decision-making arc

To address mind-set challenges, companies can frame and simplify choices to reduce mental processing, and help people understand the importance and relevance of acting by showing the potential outcomes that may result. This increases the chance that the options they offer will be apparent and thoughtfully considered by consumers.

Next, companies can tackle consumers’ perceived ability to act by offering sufficient structure, defining the value of options and communicating that a path forward seems achievable and relevant. Here, it’s important to strike a balance to provide the right level of consumer control, depending on their level of confidence and competence to make smart choices (or make choices at all).

Finally, companies can identify prompts that drive action using a constellation of tactics—social encouragement, a sense of urgency, even taking choice away through automation—to create smart solutions that streamline action.

Considering this full decision-making arc, and how each phase feeds into the next, should not be underestimated. Insufficiently addressing user mind-sets may mean a company’s offering is never even considered; had Allianz’s SMarT plan been perceived as just “for rich people,” it may not have gotten as wide an audience. Even for consumers inclined to believe in the value of 401k savings plans, barriers such as perceived difficulty in choosing funds, or a requirement that consumers needed to find time to meet with an advisor, may have inhibited sign-ups insurmountably. Finally, Allianz used auto-enroll and auto-increase mechanisms to help ensure that users actively joined and participated in the program. Designing with a holistic experience in mind helps reduce the chance that users will freeze and fail to follow through.

Mind-set: Helping consumers define their options

Consumers are often overwhelmed when they’re offered too many options. Companies can err on the side of providing more—or more detailed—information in an effort to help people understand and choose. But providing a plethora of information can complicate matters further by increasing information overload, when reducing mental processing is usually more effective. This can be accomplished in a few ways:

Limit options and add structure to combat choice overload

Explicitly crafting how choices are framed and perceived can help people more readily compare and select the “right” option. This is sometimes known as “choice architecture,”17—when organizations simplify or structure a set of options to make decision making easier, thus improving peoples’ ability to make comparisons and assess their choices. For example, Weight Watchers’ points system uses points as stand-ins for calorie counts, translating the complex calculus of food selection into a simpler math problem.18

Explicitly crafting how choices are framed and perceived can help people more readily compare and select the “right” option.

Adopting a structure that ranks or organizes elements in relation to one another can help consumers prioritize options even more. Consider two examples from your local supermarket: The toothpaste aisle has many products on display but no obvious underlying structure for how they are organized. As a result, consumers can get confused or feel overwhelmed due to their inability to judge between options. Meanwhile, the milk section has a built-in structure that helps consumers hone in on choices: Brand or container size aside, the basic choice now becomes skim, 1 percent, 2 percent, or regular milk. Because these items are conceptually organized in a familiar way, consumers can much more quickly comprehend how options compare and make choices accordingly.

Items that are not ranked on a numerical scale can still benefit from simplification and structure: Ranking options can help consumers narrow their options. In 2008, the Proctor & Gamble Company conducted user research to determine perceptions of shampoo and help them reposition their Pantene hair product line. The findings from this research—indicating that consumers were overwhelmed by the variety of choices—informed a new strategy to restructure the hair product’s lineup around a limited number of options with simple, meaningful attributes: fine, normal/thick, curly, and color-treated. Sales increased with the recognition that less choice, not more, was desirable to consumers.19 In fact, the perception of choice is often more important than the actual degree of it; Wegmans retail stores provided anywhere from 331 to 664 magazines to choose from, but research indicated that the number of categories, not the actual number of periodicals, had a greater impact on consumers’ perception of varied choice and contributed to a preferred shopping experience overall.20

The perception of choice is often more important than the actual degree of it.

More complex decisions can benefit from the introduction of a recognizable mental model, or analogy, to provide an alternate kind of structure.21 Online shopping sites use icons and terms like “your shopping cart” and “checkout” that lean on a familiarity with bricks-and-mortar contexts, simplifying consumers’ mental processing by association. This helps explain why, after a lifetime of exposure to health plans culled and provided by employers, many consumers freeze when negotiating the sea of Part A, B, C, and D Medicare options. With no analogous mental model to work from, consumers are forced to build a new one, and often respond by simply avoiding this stressful task.

Create options that resonate

Another mind-set that companies must design solutions for is when consumers aren’t sure if any option feels right, and thus avoid making any choice at all. When companies understand and design offerings that speak to potential consumers’ values and identities—either as an individual or as part of a broader group—they can create a bias toward action where none existed.

For example, in 1986, the Texas Department of Transportation developed a public service campaign to combat littering along its highways. Initial versions appealed to tidiness, which, for the young men who were the primary culprits, felt more like a “clean your room” lecture from mom than a call to action. In contrast, the eventual campaign—“Don’t mess with Texas”—tapped into a sense of protectiveness and pride over one’s turf that positioned anti-littering as a tough-guy rallying stance. This now-famous campaign is credited with reducing litter on Texas highways by roughly 29 percent in its first year to 72 percent within 10 years.22

Perceived ability: Helping consumers feel confident about their ability to choose

The next major intervention point for companies to consider occurs when people have an initial hunch about what to do, but then hesitate indefinitely due to lack of confidence about how to act. If a consumer’s lack of confidence about making a good choice is strong enough, it can keep them from participating in a retirement plan at all, even if logically they fully understand the importance of building a nest egg. To counter this urge, companies can try a few different strategies:

Creating context to indicate what “good” looks like

Companies can dial down consumer indecisiveness by pointing to examples of those who made a choice. In this way, they can help consumers feel like abstract decisions are more achievable by providing concrete examples of what others have done. Amazon’s “People who bought X also bought Y” feature—an example of social proof, in which people tend to follow the lead of others—not only reinforces the idea of making the “right” purchase by indicating whether previous customers bought an item, but also expands upon it with suggestions about additional items to purchase. In a similar way, Empower Retirement’s “How do I compare?” tool provides consumers with the ability to benchmark their contribution rate and balance against the top 10 percent of peers with the same gender, age, and approximate income. In one sample, 5,000 out of 30,000 participants increased their contribution after using the tool, by 25 percent.23

Demonstrating what to do

In the case of retirement fund selection, making a choice may be difficult, but the process—filling out a form—is not. In other cases, however, paralysis can set in when people are uncertain about steps that are required to move forward. Albert Bandura coined the term “observational learning” to describe how the demonstration of an action by performing the behavior—“monkey see, monkey do”—can make an otherwise mystifying situation seem doable.24

The proliferation of YouTube tutorials and channels that have sprung up for anything from makeup application to fixing a leaky faucet are real-world examples of this, breaking complex actions into small, bite-size steps, with checkpoints of achievement that dot the path to success. Behavioral modeling builds confidence simply by showing what is possible: If I can see how you did something, I have much higher confidence that I can do it, too.

Making the future more conceivable

In situations where decisions have long-term implications, and the future is hard to envision, consumers frequently stop in their tracks. Research about Millennials planning for retirement, for example, has indicated that their difficulty with long-term saving is only partly due to a lack of funds, and rarely because they don’t recognize its value. Rather, the concept itself is difficult to grasp because they can barely conceive of having careers, let alone retiring from those careers25—the highly abstract concept of “retirement” makes it nearly impossible to prioritize 401(k)s ahead of current demands.

Companies can employ creative solutions to combat this tendency, however. Bank of America’s online discount brokerage service, Merrill Edge, developed a tool to make the future feel more real for people in a surprising way. Their Face Retirement program “ages” an image of a user’s face through software to make a future version of himself more tangibly alive.26 To make the scenario seem even more real, this virtual time machine is accompanied by statistics that project future prices of household staples like milk and utilities. Seeing a simulated future self has been shown to prompt 60 percent more people to investigate retirement options, and research from Stanford University suggests that this ability to visualize our future selves also increases people’s tendency to contribute to retirement.27

Increasing consumer confidence

In some situations, no demonstration of the future, no matter how compelling, can reduce the paralysis caused by a sheer lack of confidence or uncertainty. The Hyundai Capital America Assurance buy-back program went a different route by introducing a guarantee to convert hundreds of thousands of potential customers into real ones. Although very few people actually used it, the presence of that guarantee galvanized action by leveraging the certainty effect, the tendency for people to feel less anxious when possibilities equal either 100 percent or 0 percent.

Offering a guarantee is not always feasible, but companies can provide an alternate sense of security by reframing and simplifying complexity to build consumer confidence. Rather than probing risk tolerance or fund selection, target-date retirement accounts use a single, very human question—“When do you expect to retire?”—that consumers can answer with confidence. This frees consumers from the burden of having to select individual options or make difficult judgments about whether they invest more aggressively. Although these accounts decrease consumer control by removing the hands-on ability to customize or rebalance assets directly, letting someone else make the decision is worth it for many consumers: By the end of 2014, nearly one-half of all 401k participants held target-date funds.28

Taking action: Prompting consumer decision making and action

While companies can help prevent paralysis by designing solutions that factor in consumer mind-sets, helping them actually take action is the real goal. Building in incentives to act—or disincentives for inaction—and reducing barriers can help companies move consumers from consideration to action.

Raising the stakes by increasing urgency

Even highly rational people can be swayed by the power of emotions. Tapping into visceral and primal urges, such as FOMO (the fear of missing out), can prompt commitment and help overcome paralysis.29 Imposed scarcity of items creates urgency by tapping into consumers’ worries about potential loss—“There’s only one left”—which can be compounded by a competitive streak—“If I don’t get it, someone else will.” Online selling platforms often harness this tendency with explicit reminders about how many items are left in stock, increasing momentum toward a shopping cart and checkout. In these cases, the tendency toward loss aversion—we hate to lose more than we like to win—is leveraged rather than avoided, and used as a device to spur action.

Even highly rational people can be swayed by the power of emotions.

Companies can also instill a sense of urgency by using scarcity of time, or deadlines.30 Knowing that options will vanish or prices will increase can make the risks associated with inaction outweigh those of making a choice. Medicare forces decision making this way: Consumers face delayed enrollment and long-term financial penalties if they fail to register by age 65. While the complexities of a new system and fears of choosing poorly may cause heightened paralysis during the decision-making process, that ticking clock forces people to act. Contrast this with retirement planning: There’s no age-based timer, and the only penalty for inaction is insufficient savings. As a consumer interviewed about difficulties with long-term planning said, “There’s no real due date for saving more for retirement . . . but there’s no real start date, either.”31 Even while 401k plans allow participants over the age of 50 to contribute thousands of additional dollars to help reluctant savers catch up, without a sense of urgency prompted by scarcity or deadlines, many consumers may continue to underinvest.

Applying personal and social levers

In addition to fear of potential losses, companies can also use emotional appeals related to social or interpersonal interactions as an effective consumer motivator. Consider two people who each make a resolution to go to the gym more often. One decides to go solo, while the other makes the commitment with a friend. Whom do you think is more likely to keep at it?

In this situation, the friend serves as a commitment device, or a means to compel an action or decision via the use of external forces. These can take different forms—a contract is a commitment device, for example—but a person’s sense of social obligation to keep promises is very powerful. Peer pressure is often positioned as negative, but here it can be a force of good; from reading groups to Weight Watchers to Alcoholics Anonymous, a person’s fear of letting others down can override her tendency toward inaction and can provide the impetus to follow through with commitments. Investment clubs provide a similar model, bringing a social angle to investing and financial planning.

A person’s sense of social obligation to keep promises is very powerful.

Companies can also invoke tactics that appeal to consumers’ senses of identity, another strong behavioral lever. In 2003, Robert Cialdini ran an experiment in which hotel guests received different messages to encourage towel reuse. When informed that most hotel guests reused their towels, people were 26 percent more likely to do so themselves . . . but when they were told that the previous guests who stayed in their room had reused them, the reuse rate rose to 33 percent.32 In a similar experiment, informing residents that other community members were planning to vote led to increased voter turnout.33 This lasso effect, known as normative messaging, plays on people’s desire to fit into the norms of a group with which one shares a sense of kinship.

Many successful solutions combine these strategies. StickK, an online habit-making and habit-breaking platform, combines tactics to combat inertia. People set goals by making a public declaration of intent on the site and selecting a personal referee who is charged with keeping them in line, both examples of social levers. Customers also commit to a financial penalty for failure to succeed, with the option of applying penalty dollars to an organization or cause they abhor. The feeling of letting people down and losing cash is compelling already, but when you add in the visceral disgust of contributing to something personally repellant, it results in a very powerful combination of motivations to help people achieve their goals.34

Reducing friction

Another way companies can prompt action is to design desirable paths in a way that make them almost too easy not to pursue. The Amazon Prime one-click feature removes the “should I or shouldn’t I?” shopping paralysis by reducing purchasing to a single impulsive click.

Companies can use opt-out mechanics to make the “right” decision a default, which helps reduce paralysis by playing to status quo bias, or our tendency to stick with defaults. Allianz’s SMarT program intentionally set saving for retirement as an opt-out option to increase program participation; inversely, being an organ donor in the US requires opting in, or actively choosing to become one. Despite the minimal effort required to sign up, national donation rates hover around 50 percent. Contrast this with countries such as Sweden, Finland, and Norway, in which individuals are assumed to be consenting donors unless they opt-out . . . and where percentage rates are in the mid-90s.35 While not always possible—creating an opt-out or default state for exercise is easier said than done—defaults provide a powerful instrument in the behavioral toolkit. Consumers’ tendency toward “effort aversion” means that the simple fact that a decision has already been made greatly improves the likelihood that they will stick with that choice.

Defaults provide a powerful instrument in the behavioral toolkit.

Finally, while the power of appealing to emotions is often underestimated in prompting action, sometimes logic wins out. Experiments by behavioral economist George Loewenstein have shown that our inability to act in our own best interest often originates from an inner conflict between our emotional “hot” state and our more objective “cold” state.36 While hot-state decisions can sometimes be impulsive—indeed, the opposite of paralysis!—in other cases, our heightened emotional state renders us overwrought, impeding our ability to thoughtfully weigh options. Predetermined stock price buying and selling, for example, allows consumers to set their investment strategies ahead of time to avoid hot-headed, impulsive actions. Here, the contracts or commitments a consumer makes ahead of time—in his rational cold state—would prevent him from interfering with his own plan of action.

Putting it all together

Multiple triggers—too many options, present state/future state tensions, and negative emotions—provide a breeding ground for consumer paralysis and inaction across diverse industries and consumer situations. Companies can call upon a multitude of strategies to address the end-to-end arc of the user experience, from consumers’ initial frame of mind to their perceived ability to engage, to actually taking action. Increasing structure and considering identity can reduce mental overload and help ensure that the right options will resonate. Showing what “good” looks like, closing the gap between present and future, and strategically reducing uncertainty can help consumers move forward with confidence. And embedding a sense of urgency, leveraging positive social pressure, and making things too easy not to do reduce barriers to action.

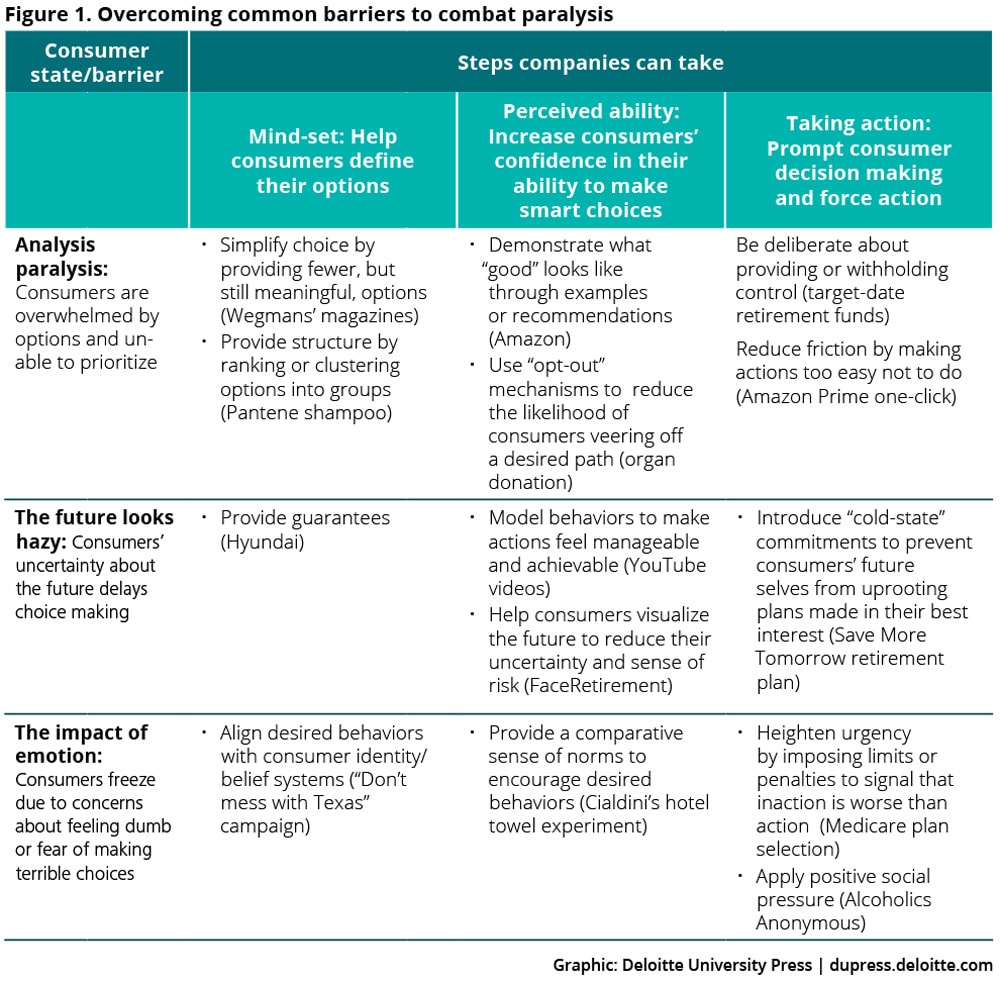

While there is no perfect formula or silver bullet to address inertia, understanding the issues that keep consumers from acting can provide valuable clues about what to try and which strategies might be most effective. Are your consumers typically confronted with too many choices and are overwhelmed by options? Are they experiencing future-state uncertainty? Do they worry about the consequences of making a bad choice, potentially amplifying their lack of confidence in making a good decision? A simple framework can help identify which strategies can be used to address common barriers at different stages of decision making (see figure 1).

And finally, three key things to keep in mind:

Treat decision making as a process, not a single point in time. Combine strategies that collectively tackle mind-set, perceived ability, and action. Companies that only adopt strategies that encourage action, for example, may fall short if consumers don’t consider their offerings an option in the first place.

Remember that paralysis can be caused by multiple triggers. As we saw with the Medicare and retirement savings examples, paralysis can sometimes be the result of multiple forces. Consider how strategies can be cobbled together to tackle difficult cases, or how they might reinforce one another to create more effective solutions.

Test and measure. As with anything, you may not get it exactly right the first time. Here, it’s important to identify which levers your company is trying to move, identify which consumer behaviors impact those measures, and then test solutions with those behaviors in mind. These steps should help companies highlight more clearly what works, identify unintended consequences, and determine what to adjust.

In a world in which both uncertainty and options will continue to grow, it will become increasingly critical for organizations across industries to adopt strategies that combat consumer paralysis. Companies that identify the problems they need to solve for, across the full arc of the customer experience, will be well-equipped to design the right interventions and interactions to address paralysis, or even keep it from setting in in the first place.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.