The Scale Paradox has been saved

The Scale Paradox Analytics disrupts the size factor

20 March 2013

Disruptive technologies, combined with analytics, can help companies on both ends of the size spectrum overcome the historic limitations of smaller and larger scale.

Overview

EXPLORE

Create and download a custom PDF of the Business Trends 2013 report.

Less than a decade ago, large enterprises held significant scale advantages over small businesses in the same industry. The enterprise advantage was one of might. The bigger the company, the more vast and diverse its resources. The most effective financial, customer, and business intelligence solutions were cost-prohibitive for small businesses.

Today, the growth of open-source platforms, cloud computing, social media, and analytics technologies has eroded much of the large-enterprise scale advantage. Even with their investments in third-party data, statisticians and data scientists, and decision-support technology, big companies are facing big challenges from small and mid-sized businesses. With open-source and cloud options that can cost more than 80 percent less than traditional systems,1 advanced analytics solutions are now attainable without extraordinary IT investments, giving smaller companies new and deeper insights into everything from customer preferences to potential new products and markets.

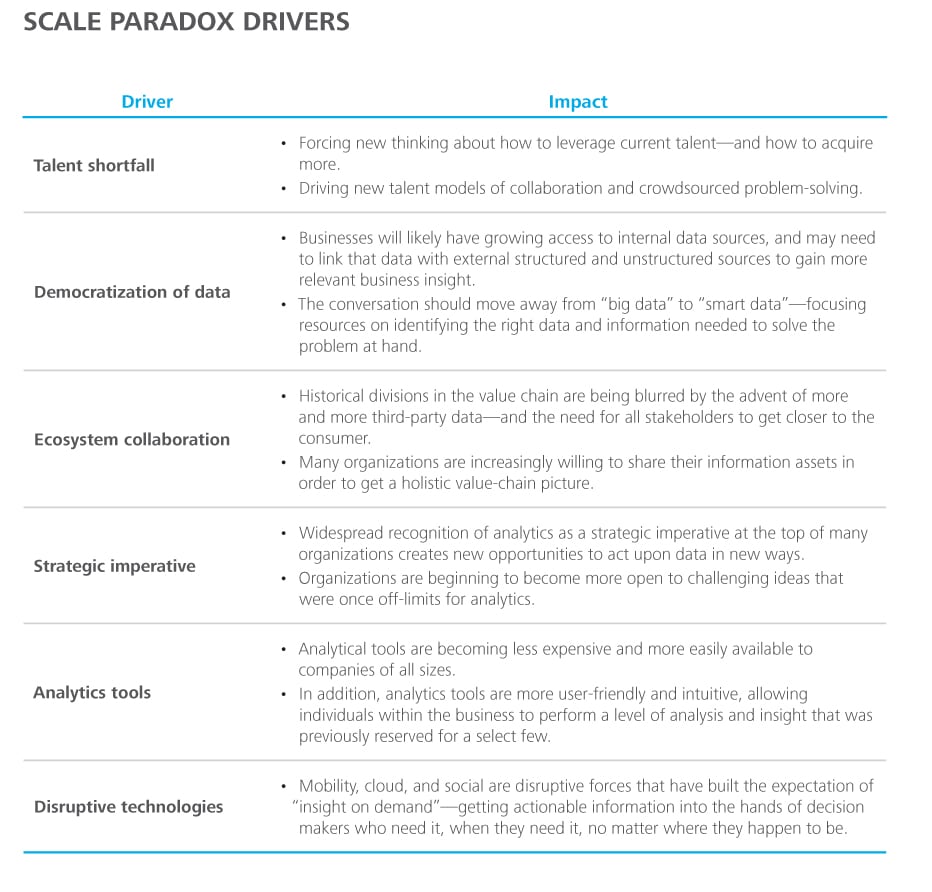

What’s driving this trend?

In addition to smaller organizations gaining access to new data and technologies, an even bigger shift is occurring in the analytics operating environment. A remarkable democratization of talent and data is unfolding; as demonstrated by the data scientist being called the sexiest job of the 21st century,2 the battle for talent is on.

Disruptive technologies continue to change how companies innovate and compete. Combined with the power of analytics, they allow small companies to achieve insights once afforded only to large enterprises. At the same time, large enterprises can use these disruptive forces to shorten the time-to-insight and innovate in ways that used to be the sole domain of much smaller and more agile startups. This is the scale paradox.

Smaller companies have been forced to innovate in order to compete on the talent front, using strategies such as crowdsourcing of analytics to engage the talent they need. Competitive predictive modeling platforms like Kaggle, with more than 60,000 data scientists worldwide,3 help both small and large companies outsource the science of data analysis. Access to top data scientists is now readily available in a bidding-style format designed to flex with demand.

Finally, the notion of data ownership and master data management itself is being challenged by innovative companies that are building repositories of information (by trading data assets) and making them available on the open market. For example, global data provider Factual owns products-and-places data that it aggregates and shares across a community of users. One leading social network uses Factual’s Global Places suite of data and application programming interface (API) when users “check in” to one of 64 million places in 50 countries. Factual in return aggregates even more data,4 making it a one-stop shop for master data for not only the social network, but for other customers as well.

In short, the convergence of all of these analytics tools are enabling a new level of insight at a more affordable price point, arming even the smallest startups with predictive powers that could disrupt almost any industry. Combined with the forces of mobile, social, and cloud, analytics capabilities can be scaled up and down without the costly infrastructure requirements of the past.

Lessons learned: What works and what doesn’t

Small business, big insights

Today’s small and mid-size businesses are using analytics to achieve a competitive advantage by more deeply understanding customers—something many customers long for and feel doesn’t occur with larger organizations. The democratization of data and the advent of more-intuitive technologies give a clearer picture of customer wants and needs, even to those executives not steeped in statistics.

Take the example of a global retail startup that had grown by leaps and bounds during its first few years in business. The company successfully scaled up, using data from a variety of sources, including social media, to better understand and connect with its customers. The company used analytics to understand “who” the consumer was and then proactively communicated with them through social media and non-traditional marketing campaigns. It built brand loyalty and engaged with the consumer to displace much larger rivals.

While large organizations can also access these new tools, small companies are often better able to adapt and embrace the creative recommendations that result. Large organizations may attempt to create barriers to entry—for example, Amazon’s recommendation engine—but they often find well-funded, nimble startups close behind with an alternative solution. Such is the case with the new publisher-co-funded book discoverability platform, Bookish.5

Big business, agile enterprise

Big business, agile enterprise

Historically, large organizations have found it difficult to execute in a timely manner, hampered by siloed information, layers of bureaucracy, and a fiscal rigor that can make agility difficult. Due to their sheer size, large companies sometimes lack the flexibility and focus necessary to use analytics effectively. With strategies that often look years ahead, large organizations can struggle to adapt outside their regular planning periods.

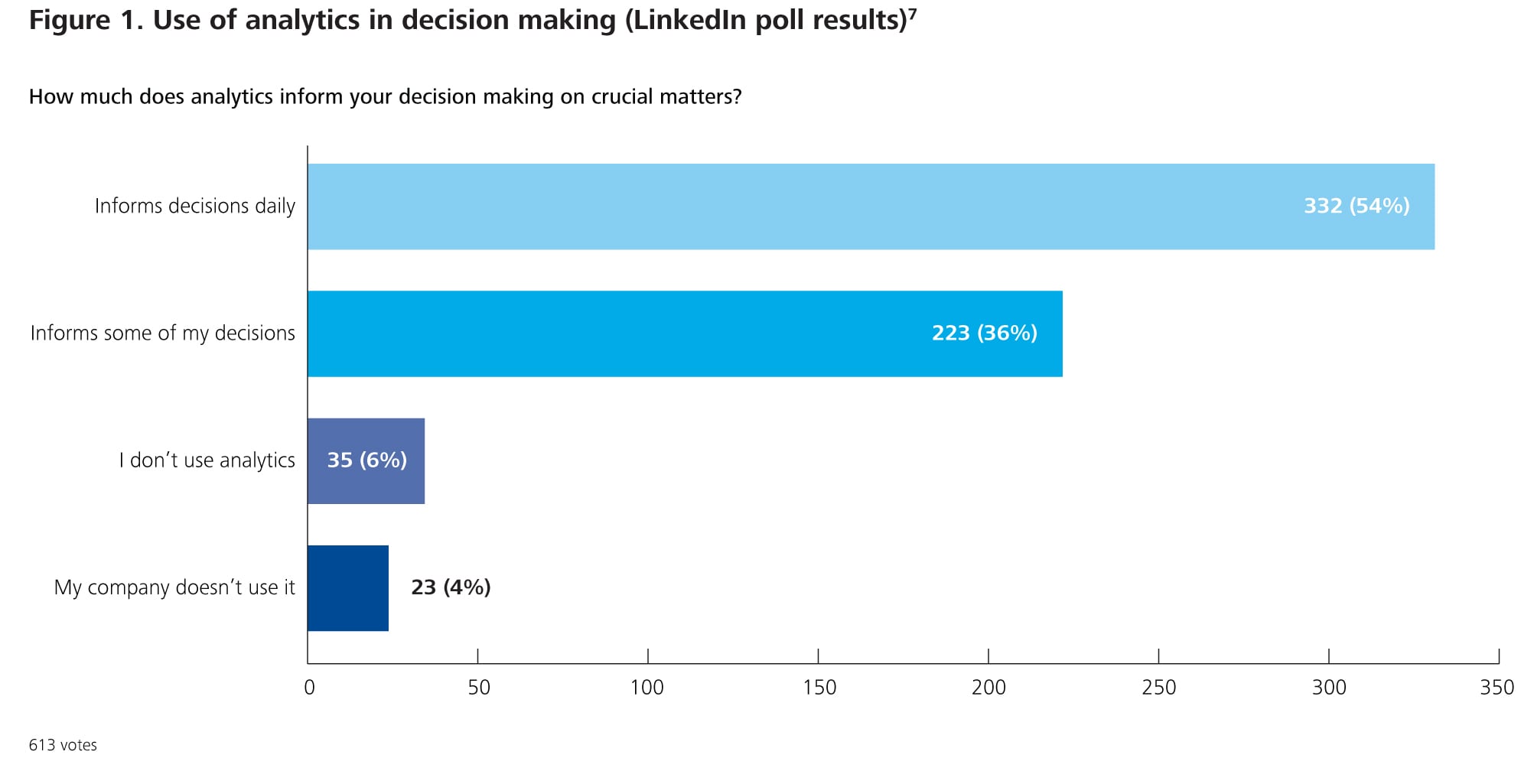

If the scale paradox allows small organizations to “punch above their weight,” it also provides the opportunity for large companies to become more nimble—what we call the agile enterprise. Analytics, in particular, can enable new levels of flexibility and agility that were once the domain of small businesses and startups. Executives surveyed at larger organizations understand the role that these new capabilities can play in daily decision making.6To capitalize on this shift, large companies should create a culture of action driven by insight.

Analytics enables greater visibility into execution as well as the ability to monitor how changes in strategy are affecting business performance in near-real time. While execution of strategy may have been center-led historically, large enterprises that take advantage of the scale paradox can learn to experiment with trial and error and other methods that enable them to be more fluid and adaptable to the pace of change.8

Such was the case for one large-scale global retailer that used analytics to push past its size barrier. Adept at collecting, managing, and deriving insights from data, the company was facing challenges around execution. Because of its size and culture, moving from insight to action was a slow process. To meet this challenge, the company developed an “insights group,” staffed by analytics specialists with business acumen, and charged it with improving decision making and financial performance across the business. In just two days, the group was able to provide decision makers in supply chain and sales with a visual representation of inventory positions that were used to resolve important product supply challenges for both organizations.

Looking ahead

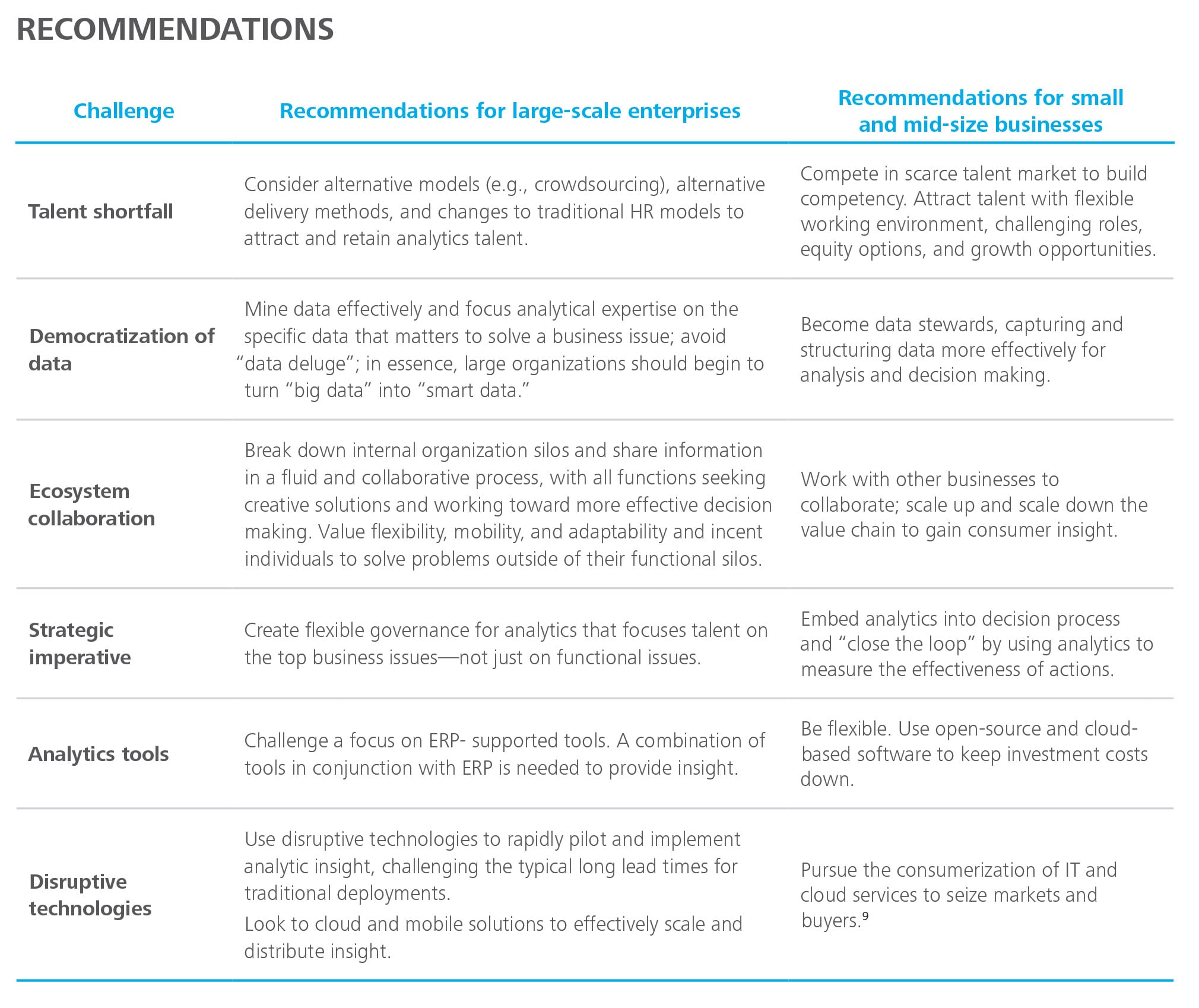

The scale paradox is pushing small and larger enterprises out of their comfort zones. From talent to tools, organizations are discovering they can—and should—create new approaches to move forward.

Large enterprises should have a good understanding of their analytical maturity before investing in talent. In addition, they should be more agile in using analytics to help set their strategy and measure its effectiveness. And most important, they should empower decision makers to adjust the execution of their strategy based on analytic measurement of its effectiveness on a much more frequent basis.

Culturally, the shift toward embracing analytics in decision making will likely accelerate. More and more companies may realize that analytics doesn’t always “answer the question,” but instead can be used to reduce the risk of unknowns, allowing leaders to focus on issues that truly require their attention.

Disruptive forces are eroding the historical scale advantage once held by large enterprises. Effectively using analytics can help address this disruption for organizations large and small.

For many large companies, becoming an agile enterprise requires a focus on execution, linking analytics to specific business issues. In many large organizations, the largest barrier to change is the cultural shift needed to empower decision makers throughout the organization to execute effectively—and then provide the analytics needed to measure results and adjust in a timely manner. Smaller organizations should retain their ability to execute with speed and precision, while taking care of their data and finding creative ways to scale up to compete with larger, resource-rich competitors.

Either way, the scale paradox in analytics represents an opportunity to achieve deeper insight and timely action, reduce risks associated with strategic and tactical decisions, and measure the impact of execution. Whether you are a large company or a small one, you can use the scale paradox to create more value for your organization and shareholders.

My Take

Tom Davenport, Independent Senior Advisor to Deloitte Analytics, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited

I agree with the authors on several points. First, it’s true that in the past, large organizations have had the advantage in building and exploiting analytical capabilities. Large banks, retailers, airlines, hotel chains, and insurers have been the primary users of analytics in their strategies. As a result, they’ve prospered and become even larger. The authors are correct that many of the factors favoring large organizations have diminished in recent years.

The authors also have the right focus on human capital—quantitative analysts and data scientists—as an important element to effectively using analytics. Software and hardware have become cheap, commoditized, and, in the case of open source, free. But human analytical talent remains difficult to source and retain, particularly if the organization seeks analysts who understand not only analytics, but also business issues and how to communicate effectively with decision makers.

In addition, there are two human capital factors that are critical to whether small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) can prosper with analytics. One works in favor of SMEs, the other against them.

The factor in SMEs’ favor is the fact that—at least in my research—many data scientists are not interested in working for large, bureaucratic organizations. When I researched them in 2012 (for the “Sexiest Job of the 21st Century” article cited by the authors), data scientists wanted timely impact, close relationships with specific decision makers, and the freedom to experiment and fail—all characteristics that are often more difficult to find in large firms.

The human factor working against SMEs in analytical competition is that many small business owners don’t have the orientation to analytics that I’ve seen in large company executives. Outside of online businesses, managers of startups don’t often think of analytics as a way to compete. Their greatest analytical limitation is their own imaginations. Perhaps this limitation will also be eased over time.