The C-suite: Time for version 3.0? has been saved

The C-suite: Time for version 3.0? Business Trends 2014

01 April 2014

The next-generation C-suite must transcend functional boundaries to secure enhanced alignment and coherence, without defaulting back to the command-and-control arrangements of a bygone era.

Overview

Learn more

Visit Deloitte.com for more on Strategy & Operations.Create and download a custom PDF of the Business Trends 2014 report.

Chief executive officers today have more direct reports than at any time in the past. The positions that collectively make up the “C-suite” in large businesses (so named because of the tendency for all of their titles to feature the word “chief”) have, according to one authoritative study, doubled since the 1980s.1 But the trend at the top of organizations is not just a matter of numbers—it’s also about composition. In C-suites today, functional specialists—including chief financial officers, chief marketing officers, chief human resources officers, and more—far outnumber the generalist heads of business units.2

If the original top leadership group of a handful of general managers constituted “version 1.0” of the C-suite, the prevalence of functional specialists puts us solidly in the “2.0” era. The problem is that this model is ill-matched to a business environment in which companies must transform themselves, and continue transforming themselves, to remain competitive. In the new era of globalization, teams of functionally oriented executives sometimes struggle to formulate and act on integrated, coherent strategies for future success.

For many businesses, it’s time for another reconfiguration of the top leadership team—here comes C-suite 3.0.

What’s behind this trend?

The C-suite is and will likely continue to be an evolving construct. The origins of a small executive team responsible for overarching enterprise leadership date back to the 1920s, when businesses were gaining unprecedented scale and regulators and shareholders demanded more management accountability. Alfred Sloan, whose years at the helm of General Motors turned it into the world’s largest company, created the prototypical model when he distributed profit-and-loss responsibility across managers of key business divisions and regularly assembled them to decide on matters above the divisional level.3 Other corporations followed suit, establishing centralized leadership groups to make critical decisions, allocate resources, provide for execution through clear hierarchical structures, and monitor performance. The typical executive team included a financially oriented CEO and several key general managers of the firm, and was empowered by a growing suite of financial tools and control and measurement systems. This leadership system endured for about 60 years. It’s fair to call it “C-suite 1.0.”

Around the 1980s, the general manager-packed C-suite came under real pressure as businesses increasingly found themselves competing on particular dimensions of performance. There were new technologies to master and competitors excelling along new lines (for example, Japanese manufacturers attending to “total quality management”). Markets were globalizing and being deregulated. GE’s Jack Welch famously warned in the 1990s that “if the rate of change on the outside exceeds the rate of change on the inside, then the end is near.”4 The work of driving “change on the inside” fell mainly to executives with technical and functional specialist backgrounds. The result was a radical shift in the composition and role of the executive team—the rise of C-suite 2.0.

A recent Harvard Business School working paper reports that there were two primary characteristics to this shift. First, the span of control broadened. As scholars Maria Guadalupe, Hongyi Li, and Julie Wulf find, “From the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s, the size of the executive team (defined as the number of positions reporting directly to the CEO) doubled from 5 to 10.” Second, the vast majority of the new additions have been “functional managers rather than general managers.”5 This leadership system, with its expanded and far more specialized composition, provided essential professional depth and strength, and contributed substantially to the ability to deliver complex and often highly technical change. By now, it has become so prevalent that the model goes unquestioned. Few can imagine that 30 years ago many large firms did not have in place chief financial officers, let alone chief marketing officers, given the critically important roles both now usually play.

Having functional specialists in the C-suite has sharpened companies’ capabilities on many fronts. Professionals in information technology, marketing, finance, human resources, sales—and more recently, knowledge management, innovation, risk management, and sustainability—have been able to continuously hone their craft. It has been mainly within functional realms that new “best practices” are identified and shared. Aiding this development is the fact that business-school curricula and in-house management training by firms are often also organized along functional lines.

But functional depth has come at a cost. Increasingly, we recognize that organizations are complex systems whose many elements interact in a dynamic fashion. When change is underway outside, it rarely means that only one function inside the business must keep pace. Many interdependent changes may be required and the need is for them to be mutually reinforcing. How is this necessary coherence and alignment achieved? It is the responsibility of senior leadership. So a serious tension exists in many leadership teams: They need to implement specific (and often technically complex and mission-critical) changes and simultaneously achieve systemic coherence in transforming the overall business.

If anything, the necessary integration seems to be getting harder to achieve. For example, one of the most obvious points of mutual interdependence in many C-suites is between the CIO and the CMO. As data-driven customer insights grow in volume, availability, and importance, the ability to capture and act on them becomes a competitive necessity. Yet, as research undertaken by Forbes and Forrester in 2013 confirms, the relationships and collaborations between those two critical executives, and their respective teams, are typically challenging and underdeveloped.6

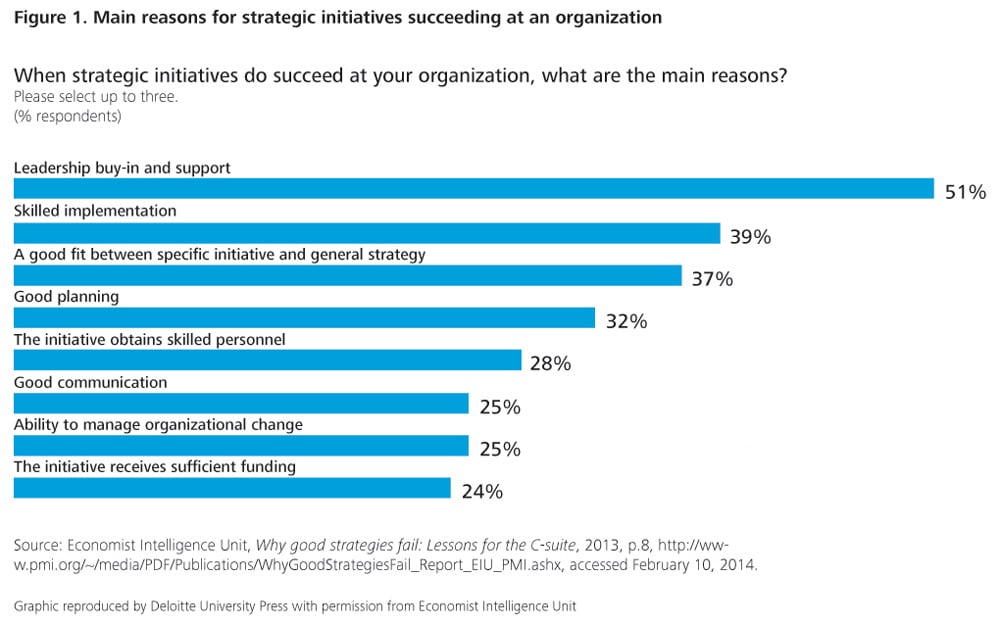

The strain shows across the organization. In a recent Economist Intelligence Unit survey, global executives identified C-suite buy-in and direct support to be by far the most important determinant of success for important initiatives (figure 1)—yet, answers to other questions showed how hard it is to get unified support from the top.7 For example, half reported insufficient collective attention from that team to the implementation of strategic priorities. Moreover, “A majority of respondents say that their companies’ activities are only somewhat aligned with their strategy across every element of the business model. Worse, the number saying they are unaligned to some degree is greater in each case than those saying they are extremely well-aligned.”8

If the 1.0 era is now easy to dismiss as “command and control,” it might be time to also fault the 2.0 C-suite’s tendency to “divide and conquer.” It has created challenges of alignment and coherence, as different forms of functional expertise—and their associated worldviews, priorities, and language systems—have been brought together at the cost of the natural integration once provided by a small team of general managers.

Given today’s constant need for well-integrated transformation along many dimensions of the business, the leadership team will surely evolve—but not revert to the original C-suite 1.0 model: The business environment is decreasingly suited to centralized, hierarchical control. The need for greater coherence and alignment across multiple geographies and functions is matched by the need for agility, adaptation, “localization,” openness, and fast learning. C-suite 3.0 should address both—and master the inevitably growing tensions this balancing act will create.

Implications

Chief executives and their boards of directors already recognize the challenges facing their existing C-suite configurations. Many are asking individual members of the C-suite to extend their roles, and make higher-level, more strategic contributions. But not everyone can become the new “hero” of the firm. Some are adding new “chiefs” to take care of complex new imperatives—witness, for example, the emergence of “chief experience officers” and “chief data officers.” But adding more players, even to take on cross-cutting responsibilities, is unlikely to bring tighter integration to the team. Others are placing new emphasis on integrative business skills alongside functional expertise when promoting new members to the top team. But that is a long-term replacement process.

These moves are smart—but they focus mainly on changing the configuration of the C-suite and individual roles with it. Looking forward, the more fundamental questions probably relate more to the overall role, collaboration, focus, and collective agenda of the top team. There are no simple, and certainly no universal, answers. But a good starting point for many will be to pose a sharper question: “In the turbulent, opportunity-rich, and challenge-laden world ahead, what is the unique role that only we can perform, and only together, for the sustained success of our business?”

Many of the answers can probably be found in the following four key areas:

- Ensuring coherence across multiple strategies

- Nurturing and protecting the organization’s most critical strategic capabilities

- Recognizing and empowering informal networks of power and influence

- Decision making supported by the “three Ds”: data, diversity, and dialogue

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Ensuring coherence across multiple strategies

The growing importance of specialist and focused functions has not only reshaped the C-suite over the last 20 years or so—it has also reshaped the role and locus of strategy-making. Over the last decade, strategy has largely devolved from the corporate level to more specific areas of enterprise endeavor. Most firms today have a broad array of distinct strategies—for example, talent strategy, customer strategy, technology strategy, finance strategy, innovation strategy, and government relations strategy—each typically “owned” by a C-suite executive. There have been substantial benefits from this more granular approach to strategy—but it has often resulted in a trade-off between strategic and operational excellence at multiple functional levels, and strategic coherence at the enterprise level.

The resolution of that tension certainly does not lie in a return to the often heavy-handed and over-centralized strategic planning practices of the past. But the C-suite is typically the only team that has access to the information, insight, skills, and influence to establish and communicate the overall strategy for the business—a critical set of integrated choices that help secure alignment and integration. To be clear—this is never a comfortable exercise in reaching easy consensus, but a tough-headed and robust process of sharing, debating, and converging.

If the 1.0 era is now easy to dismiss as “command and control,” it might be time to also fault the 2.0 C-suite’s tendency to “divide and conquer.”

Procter & Gamble has long deployed one pragmatic approach to heading off fragmentation without disempowering either its specialist functions or the next levels of leadership and management of its businesses. CEO A. G. Lafley and Roger Martin, long-time dean of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School, describe it in their recent book Playing to Win as a “Choice Cascade.”9 A set of choices at the highest level of strategy—regarding the business’s long-term goals and aspirations (mission, purpose, and vision)—is followed by clear definitions of “where to play” (in what markets, geographies, and customer segments) and “how to win” (with what differentiated capabilities, which must be created and sustained).10 In a period of growing disruption and proliferating options, part of operating in the C-suite 3.0 mode will mean using a process like this to regain the power of a clear, shared, and choice-based corporate-level strategy.

Nurturing and protecting the organization’s most critical strategic capabilities

Various schools of thought regarding strategy have focused on differentiated capabilities as a foundational source of sustained advantage. Michael Porter described the role of “activity systems,”11 Hamel and Prahalad defined “core competencies,” and Kees van der Heijden pointed to the cohering “business idea.”12 All these concepts call for the identification, development, and protection of strategic capabilities that are hard to replicate and that work together systemically. These can be surprisingly enduring—some corporations’ activity systems described by Porter almost 20 years ago remain powerful strengths today. But they are hard-won, and need to be carefully nurtured: They are sometimes eroded by well-intentioned initiatives, narrowly defined efficiency moves and cost-reduction programs.

In a disruptive environment, fresh emphasis must also be placed on the development of new organizational capabilities. These vary, obviously, from industry to industry and from firm to firm. But, for example, a company might recognize the advantage it could gain from a strong capability to collaborate or engage in co-creation in its innovation efforts. It might develop a distinctive capability in gathering (and interpreting) data from multiple sources. Or it might cultivate strength in attracting and mobilizing nonprofit or public sector partners.

Very rarely can the most critical strategic capabilities be created and sustained entirely from a single function or part of the enterprise: They are built from smart, cross-cutting configurations of assets and involve high interdependence and collaboration. It therefore will be an increasingly vital role of C-suite 3.0 to ensure that enterprise-level capabilities are clearly identified, their dependencies crisply defined—and any high-impact initiatives scrutinized in terms of whether they will enhance them or, at a minimum, protect them from degradation.

The ongoing evolution of the C-suite and the critical integrative role it must perform are likely to have far-reaching implications across many firms.

Recognizing and empowering the informal networks of power and influence

Seasoned C-suite advisor Bob Frisch has described the typically dominant sway of “the team with no name”;13 business writer Art Kleiner identifies the massive influence of the “core group.”14 Both are describing a reality seldom made explicit: The formal leadership system is invariably shadowed by powerful, informal networks and relationships of consequence. This is a fractal phenomenon in most organizations, with a repeating pattern of “kitchen cabinets” surrounding individual senior executives. One of the most important groups is the one structured around the CEO, usually including several (but seldom all) C-suite members along with other insiders and, often, external advisors.

The effective C-suite response is usually not to attempt to “remedy” this by reclaiming its rightful status, but to embrace the reality of the firm’s power and influence dynamics. Failure to understand and acknowledge these undocumented, distributed, trust-based arrangements often causes frustration and dysfunction. But when recognized and incorporated into the leadership processes, they can add considerable value. The most senior “team with no name” can help the CEO make quick decisions with confidence and conviction. The fractal networks of such teams can help scale and disseminate those choices, and help align and integrate action in their support rapidly and pervasively.

The executive committee of heavy building materials firm CEMEX understands these networked dynamics well, and has established distributed global leadership networks to promote more collaboration, information sharing, and the spread of best practices for each of its primary strategic priorities. The company has also designed and integrated all of its leadership development processes around strong network principles, systematically connecting the top executive team, its direct reports, and high-potential populations in all leadership training programs.15

When networked leadership arrangements are carefully designed and incorporated, bewildering obstacles to clean implementation of important changes often evaporate. Add the growing prevalence of top leadership support to informal “communities of practice” and other emergent networks, all enabled by social media, and the energy to be tapped is impressive. The “off the chart,” invisible organization can greatly enable any innovation, adaptation, and dissemination of good practices that the C-suite 3.0 hopes to catalyze in a period of disruption and change.

Decision making supported by the “three Ds”

In an increasingly volatile and uncertain world, companies are likely to rely more, not less, on the judgment of managers in making critical decisions and choices. A fundamental and unique role for most C-suites is the application of collective knowledge and experience in exercising judgment on the most critical issues—and enabling others in the enterprise to do likewise. To do this more effectively, top management should consciously review their approaches to decision making, and determine how these might be enhanced by thoughtfully designed support from the “three Ds”: data, diversity, and dialogue.

From the worlds of social psychology, behavioral economics, and most recently, neuroscience, a great deal has been learned about the reality of how humans make decisions, individually and in teams. It is typically a far less rational process than assumed. The power of heuristics and biases, the dangers of certitude, the risk of reliance on experts—these and other factors are well understood. But with the convergence of disciplines, and an increasing focus on techniques for better team-based and individual decision making, this is a field starting to move from the world of theory into the world of practice.

Then, there are the opportunities afforded by exponentially increasing access to hard data. The hype around big data reflects real promise in the form of greater transparency and insight, delivered through executive dashboards and powerful and intuitive visualization technologies. Judgment will never be replaced by data—but it will be increasingly supported. Access to sound information in close to real time can enable the C-suite to agree on necessary course correction, focusing on facts from the field rather than the specific (and sometimes competing) interests of different functions and executives.

But data are sometimes tortured to “reveal” whatever the interrogator wishes to learn: They do not always overcome inevitable cognitive biases. Two other opportunities for enhancing judgment come from the “softer” domain of social science. Few executive teams today are as diverse in their composition as their talent base and the markets they serve. But that is changing, with global experience and background becoming more highly valued, and the evidence mounting of the benefits of designing leadership systems to accommodate greater diversity.

Difference also brings challenges—of conflict, misunderstanding, and misalignment. Here, a great deal has been learned, and codified, about the skills that underpin productive dialogue. These are learnable skills that can transform the effectiveness and outcomes of senior executive communication and interaction—and some leading firms are already investing heavily in building such leadership capabilities.

Looking ahead

The ongoing evolution of the C-suite and the critical integrative role it must perform are likely to have far-reaching implications across many firms. A recent Harvard Business Review article reports that some CEOs are already “double hatting” key executives, giving them significant responsibilities beyond their official jobs—for example, a functional chief leading an integrated operational initiative.16 Some specific “chief” roles are likely to evolve and grow. Relationships between leadership teams and boards will perhaps realign. Promotion paths to top leadership will likely take on some new contours. It is even possible that belonging to the “top team” will cease to be the permanent destination (which results in potential calcification of the team), but become a time-bound tour of duty for executives prior to returning to their own specialist areas.

It will be up to top leadership, too, to address the perennial challenge of balancing different time horizons. Top executives carry unique responsibility for both short-term performance and long-term stewardship of the firm. Intense pressure from capital markets for immediate results, coupled with a shortening average tenure for some senior executives (especially CEOs), have underscored the former in many Western corporations. Two factors are likely to enforce a more balanced perspective here. First, axiomatically, discontinuity demands anticipation—to avoid catastrophic and irreversible missteps. Second, in most industries, the competitive set now includes powerful new players who might secure advantage from a traditionally stronger orientation toward longer-term horizons, enabled by the more patient capital support of their state- and family-owned legacies.

Finally, one of the most profound changes in the years ahead might well come in the area of executive incentives and metrics designed explicitly to encourage more aligned and collaborative leadership, and to help ensure a balanced focus on short- and long-term imperatives.

My take

By Roger Martin, Premier’s chair in productivity and competitiveness and former dean at the Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

As companies have gotten larger, more complex, and more globally distributed, the job of managing them has become harder. Creating sustainable competitive advantage is also more difficult. And against this need for managerial innovation, the last major organizational breakthrough arguably was the move from functional structures to product-line structures. That shift is now almost 50 years old.

Given the gap between the tools that management has and its growing challenges, we have seen a greater level of disquiet in the C-suites of global firms. It is a generalized level of discomfort—and I don’t think there is a shared sense of the problem behind it. However, executives feel increasingly buffeted and have a general awareness that they may need some capability that they have yet to develop.

I’ve been suggesting for some time that the competency most required by senior executives is integrative thinking. Integrative thinking is a way of holding multiple conflicting points of view at the same time, and rather than being overwhelmed by the discomfort and ambiguity that results, leveraging it to formulate new, better answers. It’s a mindset and a practice that seeks to link models and perspectives, even when those points of view openly contradict one another or are based on opposing logical structures. When practiced well, integrative thinking allows leaders to develop strategies that are elegant even in the face of the fuzziness that inevitably exists at the intersections of functional domains.

To take one example: The reason why it is hard to think about marketing and operations simultaneously is because each of these disciplines has a truly distinctive set of inputs, outputs, underlying assets and theories. There is some overlap, of course, but not that much when you get right down to it. Operations links to the factory and to operations research theory, while marketing links to the buyer and to the discipline of psychology. When they come into conflict—and they do—there are very few C-suite executives in the world who have the capacity to really pull together and knit the best of the warring perspectives into a higher understanding that productively cuts across both.

As a starting point, the C-suite will need to get comfortable with being uncomfortable. The CEO has a special role to play in modeling that behavior, but so does the board of directors. If the board says, “Only bring me things that are free of ambiguity,” they are setting a tone that is hostile to integrative thinking. The C-suite must become the place where uncertainty is not only acknowledged, but embraced. And the dialogue among the board, the C-suite, and the rest of the organization must be one in which choices can be made as wisely as possible, by accepting both the known and the unknown, the knowable and the unknowable, and creating strategy in the face of both.

The bottom line

The bottom line is that if a company sticks with the C-suite model it probably has in place today, it might find it hard to remain competitive. The next wave of globalization is bringing unfamiliar opportunities and challenges, along with increased diversity and complexity. These dynamics are intertwined with rapid technological change and fast-evolving business models, industry structures, and organizational forms. Plotting the course forward will test the limitations of the typical team of functionally oriented executives.

A key requirement for the next-generation C-suite will be the ability to secure alignment and coherence across multiple dimensions of essential change, without defaulting back to the command-and-control arrangements of a bygone era. Achieving deeper integration and coherence is unlikely to be achieved by C-suite 2.0 fragmentation—but neither will it be accomplished by a return to the smaller, tightly centralized C-suite 1.0 model. Boards and CEOs might make this a subject of discussion and debate, and come up with their own definition of their future C-suite 3.0.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.