Introduction has been saved

Introduction Navigating the next wave of globalization

01 April 2014

New consumers. New collaborations. New leadership. How will the next wave of globalization impact your organization?

Learn More

Visit Deloitte.com for more on Strategy & OperationsCreate and download a custom PDF of the Business Trends 2014 report.

Globalization—broadly defined as increasing worldwide integration and interdependence, based on the flow across national borders of goods, services, capital, people, ideas, cultures, and values—has been an enduring driver of change and development. While the overall trajectory of increased worldwide engagement and interaction has been sustained over many hundreds of years, the process has not been smooth or continuous. A hundred years ago, in the buildup to World War I, many decades of global economic integration—sometimes referred to as the “Golden Age”—were rapidly reversed: Meaningful globalization did not resume for around 40 years.

Most senior leaders today cut their managerial teeth during a period of deep and rapid global integration. From around 1980, and for almost three decades, global trade increased at about 7 percent per annum on average—twice the rate of growth of global GDP.1 This extraordinary dynamic was empowered by the interplay of three key factors: falling transportation costs coupled with increasingly efficient logistics; radically faster, better, and cheaper communications, including the rise of the Internet from the mid-1990s; and increasingly supportive policy regimes, especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Despite growing resistance in some quarters to the impacts of globalization—especially related to charges of growing inequality and the exploitation of people and the environment—a strong consensus emerged in the worlds of policy, economics, and business regarding both its “rightness” and its apparent inevitability. But today, serious and legitimate questions are again being posed regarding the future of globalization.

The widely respected chief international economist of Morgan Stanley, Joachim Fels, recently put forward a “tentative thesis” that 2013 might prove analogous in some respects to 1913. He points to the rush of liquidity into emerging markets (fueled by Western monetary policies after the 2008 financial crisis)—a trend that is now clearly reversing—and the recently growing evidence that many Western companies are repatriating parts of their production processes.2 However, these are not the only reasons to question the current status of globalization.

In 2009, following the financial crisis and during the consequent recession, global trade plummeted, and while it has subsequently bounced back, it has not been increasing much faster than global GDP—far below the long-standing trend line. Capital flows have decreased even more substantially, and have still not returned to their pre-financial-crisis levels. While there has been no significant resurgence in traditional tariff-based protectionist measures, less blatant impediments to free trade have been growing: A recent report by Global Trade Alert identified 431 new “backdoor” protectionist moves—in a single one-year period.3 China, India, and others are becoming increasingly important rule- and norm-makers, not simply takers—notably in industries such as life sciences, where they are actively challenging Western intellectual property and pricing standards. The United States, motivated by security concerns, has blocked recent market entry attempts by Chinese companies.4 Notwithstanding the modest success of the December 2013 Bali summit of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) Doha round of trade liberalization reforms, most trade agreements in recent years have been regional or “preferential” rather than global. Bearish scenarios for the future of the hugely consequential BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) economies are gaining support as each shows signs of weakness along with a recent slowdown in growth. The short-term impact on some emerging market economies of the US Federal Reserve’s imminent “tapering” of asset purchases could prove highly disruptive.

Given these clear indications of uncertainty and possible disruption ahead, it would be foolish indeed to predict a single scenario for the future of the global economy. Yet business leaders must continue to act with conviction, even in an era of growing complexity and disruption. The opportunities and challenges are too great to adopt a “wait and see” stance. The purpose of this report is to inform such action through the identification of important and robust trends that will certainly matter for years to come—in all but the most extremely catastrophic scenarios for the future of globalization.

Two critical and related foundations underpin most of these trends. First, the center of gravity for the world economy has obviously shifted profoundly over the last 20 years, blurring the previously stark distinction between the developed (primarily Western) economies and what was until relatively recently described as “ROW”—the entirety of the rest of the world. Second, this rebalancing of economic might is inevitably creating a far more complex and diverse environment for business. The “next wave of globalization” includes powerful new actors, and it is multipolar, not a straightforward rollout of Western practices, standards, and values.

In many respects, both of these foundational shifts are obvious—but the magnitude of the changes underway, and the extraordinary scale of their implications, challenges many deep-seated assumptions and can be hard to comprehend fully. Here, a brief historic overview is helpful.

Look back five hundred years, and we witness a very different world. In 1500, global differences in per capita wealth were extremely small.5 China overtook India after 1700 as the largest economy in the world (and would remain so well into the 19th century).6 China had also been, for well over a thousand years, a source of remarkable innovation: the compass, rudders, paper, pasta, crop rotation, gunpowder—the list of Chinese inventions is impressive and long. Indian scholars created the concept of “zero,” upon which the Islamic universities of the Middle East had subsequently built modern mathematics. Those same universities also constructed the modern method of scientific discovery, based on hypothesis setting and iterative experimentation. Discovery, innovation, and invention were widely distributed—and Europe was, since the fall of the Roman Empire in the eighth century, a relative backwater: violent, divided, and fragmented. But that continent was entering a period of “renaissance” and would soon drive the creation of the modern world.

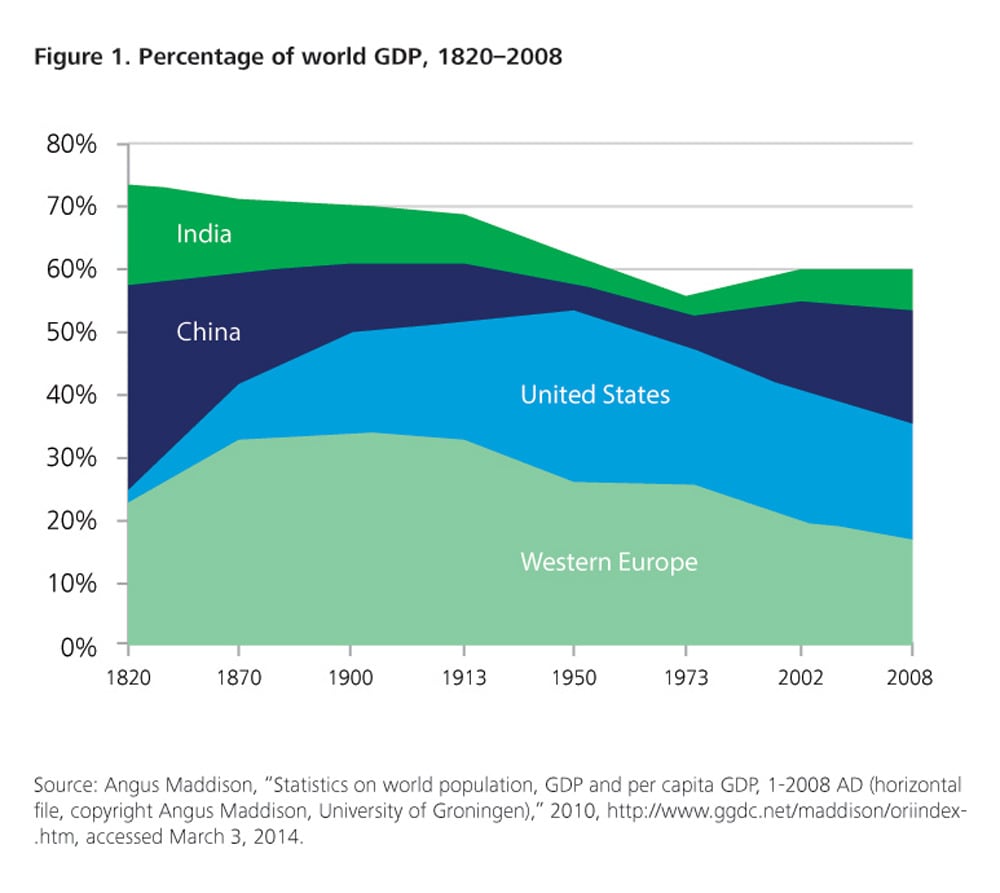

In the 18th century, Europe was home to the twin forces of modernity—the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution—and a remarkable period of global transformation followed. Europe—followed by North America—enjoyed astounding levels of economic growth and separated rapidly from the rest of the world. Economic historian Angus Maddison obtained telling data from his research, represented in figure 1.

This massive divergence of “developed” and “less developed” economies continued throughout the 20th century, leading to a growing disparity between the richest and poorest countries—a ratio of about 10 to 1 in 1900, increasing to around 60 to 1 by 2000.7 One important consequence of this sustained dynamic was a fundamental shift in global demography. As people become wealthier and receive higher levels of education, they have fewer children—a process greatly reinforced by birth control techniques. As a result, population growth has stalled—and in some cases, significantly reversed—in the richer countries, and accelerated elsewhere. For example, in 1950, the population of Europe was about two-and-a-half times the population of Africa. By 2000, the population of Africa was the larger—and it is projected to be almost three times that of Europe by 2050.8

The resulting state of the world by the latter years of the 20th century—sometimes caricatured as rich old millions in the West and poor young billions in the rest—was, arguably, unsustainable. And it has of course been transforming, in large measure as a direct consequence of the decades of intense globalization dating from around 1980.

In the first decade of this century, the world changed profoundly. Twenty-one countries (all of them developing economies) more than doubled their GDP.9 The BRICs—home to around 3 billion people10—collectively quadrupled their GDP,11 emphatically dwarfing growth in the United States (18 percent GDP growth over the same decade), the United Kingdom (18 percent), and Germany and Japan (both less than 10 percent). In aggregate, developing economies grew at an average annual rate of 4.4 percent. They have contributed substantially more, even in absolute terms, to global GDP growth than the developed economies for more than a decade.12

These rapid gains have been matched in other critical areas beyond economic growth. For example, in China, life expectancy has increased by more than 30 years since 1960, while participation in secondary education has increased from little over one-third as recently as 1990 to over 80 percent today.13 Business start-up rates during the five years between 2006 and 2010 were an astonishing 40 times greater in the BRIC economies than the rest of the world.14

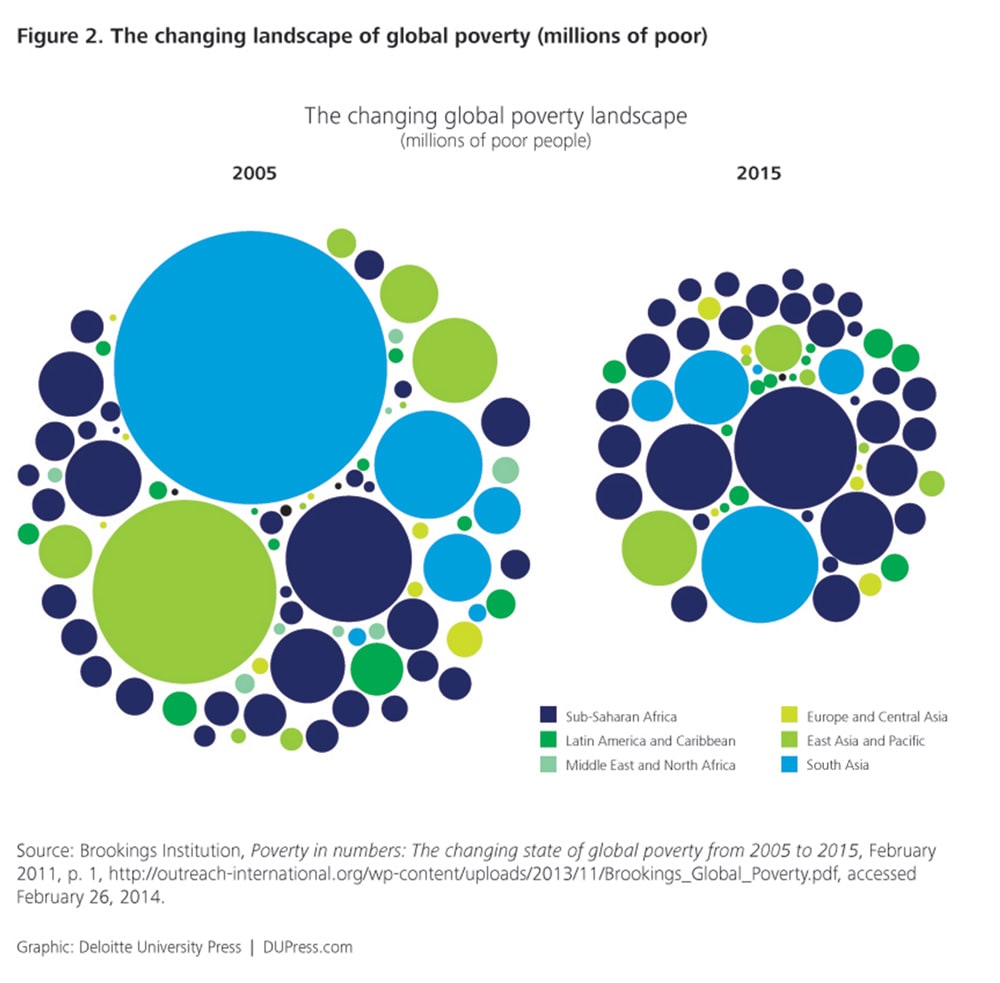

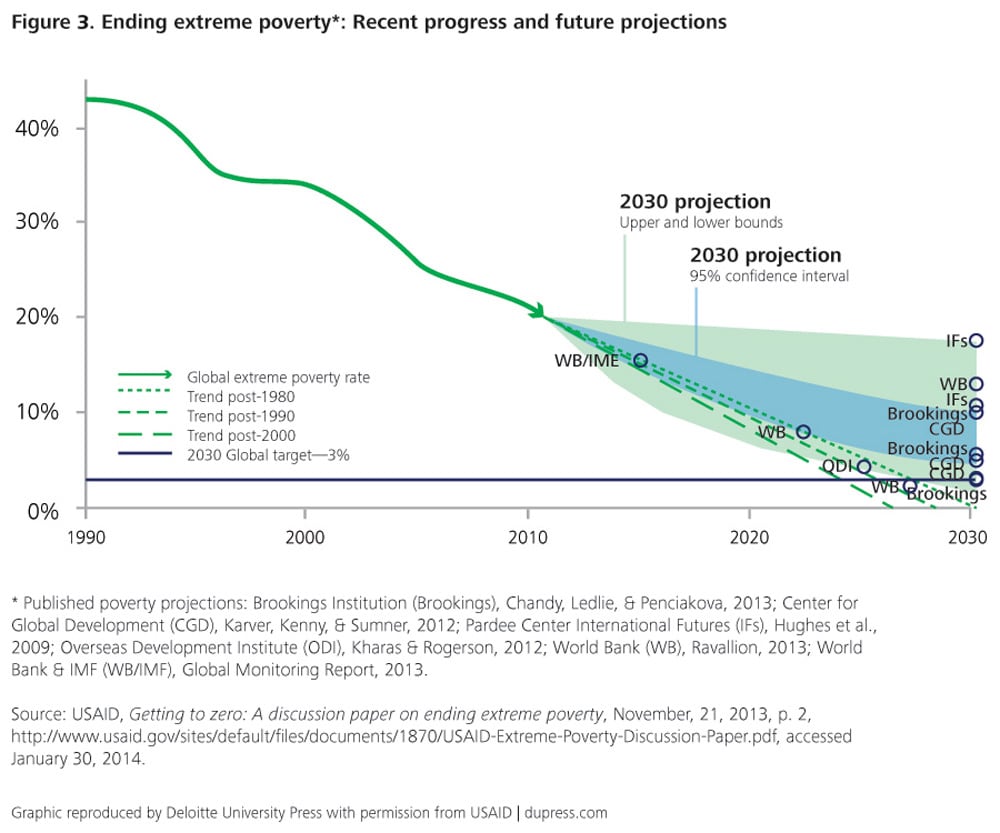

Massive inroads have also been made in the radical reduction of extreme poverty around the world. The infographic in figure 2 illustrates the reduction of poverty now forecast between 2005 and 2015—and this follows on the heels of similar reductions that have taken place for the past 20 years. In fact, according to research by Chandy and Gertz of the Brookings Institute, the percentage of the world’s population living in extreme poverty could be on track to reduce from over 40 percent in 1990 to as little as 10 percent next year15 (though other commentators anticipate a more modest reduction, to just below 15 percent16). The 1.2 billion people in extreme poverty as of 2010 constituted 20.6 percent of the developing world’s population—that is, 700 million fewer than in 1990, more than halving the poverty rate in just 20 years.17

It would be foolish, of course, to suggest that the gap between the developed and developing economies has closed, or will do so soon. The US economy is still almost twice as large as China’s, and Germany’s almost twice as large as India’s—and the gaps remain vast on a per capita basis. The worst impacts of the Western financial crisis and recession appear to be over. The United States’ economy grew by 1.9 percent in 2013 and is expected to grow by 2.8 percent in 2014, and while the Eurozone has only recently emerged from recession and had negative growth of 0.4 percent in 2013, it is also expected to resume growth at a rate of 1 percent in 2014.18 Moreover, each of the BRIC economies has slowed down recently, and each displays signs of stress. China’s shadow banking system and the prospect of a speculation bubble bursting; India’s overdue labor law reforms and governance weaknesses; Brazil’s infrastructure problems; Russia’s commodity dependency—all are legitimate and well-documented causes for concern.

But it would be even more foolish to assume that the seismic shifts witnessed over the last 20 years are over. The “slowing” economy of China grew at 7.7 percent in 2013, and it is forecast to show roughly equivalent performance in 2014; India grew at 4.4 percent, with a 2014 forecast of 5.4 percent.19 And the BRICs are hardly the only show in town. With the exception of 2009, sub-Saharan Africa has averaged annual growth rates of more than 5 percent over the past decade—and its growth is forecast to continue at around that level.20 Jim O’Neill of Goldman Sachs, the originator of the BRIC acronym, has recently created a new one—MINT (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, Turkey)—which he identifies as additional high-growth and high-potential economies.21 Thailand, Vietnam, Poland, and the Pacific Coast nations of Latin America—as well as many others—might also hold real future promise. Meanwhile, demography continues to favor many developing economies over the more mature nations. They are enjoying the “demographic dividend” associated with a healthy “potential support ratio” between those of working age and those of non-working age—which is heading into uncharted low territory in many industrialized countries, most notably Japan, Italy, and Germany.22 The fundamental rebalancing of the global economy is likely to remain a persistent dynamic for many years to come.

This spread of prosperity and opportunity is welcome and a potential source of long-term growth for enterprises from all parts of the world. But it is also substantially increasing the level of complexity and uncertainty in the business landscape. Twenty years ago, it appeared plausible to many that the “Washington Consensus”23—essentially an agenda and rule set established primarily by Western governments and Western-led global institutions—might provide a permanent framework for the future of the global economy. That scenario appears far less credible today. China, having recently overtaken the United States as the world’s largest trading nation,24 is central to new alliances and partnerships that have no Western involvement—including, importantly, a rapidly growing and deepening relationship with the continent of Africa. Many important trade, cultural, and political linkages are decreasingly led by or dependent upon Western actors. Recently released UN data show that the share of south-south trade in total world exports doubled in the last 20 years. Its share now stands at 25 percent, and is set to rise further.25

Perceptions of the appropriate role of government vary substantially, too. The rise of so-called “state capitalism”—a model that coharnesses the power of markets with powerfully interventionist government practices—is historically, culturally, and philosophically more resonant in many developing economies than purer free market capitalism. The result is a trend toward increasingly divergent policy regimes—and a rise in preferential, if not openly protectionist, behaviors as governments around the world seek to promote a growing portfolio of “strategically important” industries, sustain and create employment for their population, and promote their national security. Standards and practices around the protection of intellectual property (which naturally tends to advantage incumbents) are also being challenged and might well continue to diverge in the years ahead.

These shifts in relationships and rules might also be accelerated by growing challenges related to sustainability, linked in particular to climate change, food production, energy, and water. These have already been important contributing factors in the difficulties encountered in the WTO’s Doha round, and are set to become increasing sources of tension. Over the next 15 years, the global population will likely increase by more than a billion; food and energy requirements are both forecast to rise by 50 percent and 40 percent, respectively; and water requirements (already under enormous stress in many parts of the world) will increase by around 30 percent.26 Each of these challenges will be compounded to an unknown degree by climate change—which is in part caused by current carbon-intensive, fossil-fuel-based energy sources, and which will almost certainly impact water availability and food production.

The next wave of globalization will bring fresh challenges on many levels for businesses and the people who manage them. As a consultant to many of the world’s largest enterprises, Deloitte is in a position—and has the obligation—to see the unfolding patterns of change. In this report, we offer a set of nine trends with real implications for managerial decision making and action. Do these represent the entire story of change? Not at all. Our selection of these particular trends reflects our conviction that, amid the turmoil of many ongoing and dynamic changes, it is possible to put some stakes in the ground. These managerially relevant trends are very robust and can be acted upon with confidence as organizations seek to grow, innovate, and achieve breakthrough performance in a changing world.

In choosing this year’s trends, we are not claiming that these shifts are products of the past 12 months or that they reached their peaks of impact in 2014. Quite the contrary: All are changes that have been many years in the making. Nor do we make a conscious attempt to cover the waterfront and describe how the new wave of globalization will hit every aspect of business management. Nonetheless, the trends we describe end up falling into three major categories of impact, and that has prompted us to present them in the order we have. The first three relate to the very deep changes companies are beginning to encounter in the nature of global consumers. The second three all reflect a fascinating shift in how business gets done, focusing on collaboration both inside and outside the walls of the enterprise. The final three identify key ways in which leadership is being challenged and changed by the next wave of globalization.

New consumers

If, as Peter Drucker so simply put it, “the purpose of business is to create and keep a customer,” then nothing could have more impact on a business than a large-scale change in its customer base. The first three trends unleashed by the next wave of globalization go straight to this core issue. Global businesses will need to comprehend the growth of consumer markets that are geographically and socioeconomically dissimilar to their traditional ones. The consumers they serve will have different needs—and higher expectations of the businesses they choose to patronize.

The first trend we note is the emergence of another billion. As noted above, extreme poverty has been in steady and meaningful decline over the last 20 years—both as a percentage of global population and, remarkably (given the continued rise in overall population), in absolute numbers of people as well (figure 3). This reduction in poverty, the direct result of economic growth, is giving rise to a greatly expanded “consuming class.” In the near term, expect to see it expand by roughly another billion people. What consumer-serving company could fail to be excited about that growth?

The problem for many, however, is that all this growth will take place in parts of the world they have not traditionally served. It is in the emerging markets of Asia, Africa, and Latin America that growth rates over the past two decades have raised income and consumption to unprecedented levels. By 2020, it is estimated that the number of people in the global middle class will amount to 3.2 billion (up from 1.8 billion in 2009).27

As consumers coming out of poverty in emerging markets increasingly shape global demand, managers will need to understand the types of products and services they seek. Understanding the complex demands of this diverse cohort will be a difficult task—they are geographically and culturally diverse, more youthful, and less affluent than their Western counterparts. But given their scale and contribution to overall global growth in consumption, the task is an essential one. Our discussion of this trend explores the needs of this consumer group and discusses the ways in which businesses must rethink their market and growth strategies to reach and serve them effectively.

Exploring the changing nature of demand points us toward another consumer-oriented trend. In emerging markets, in particular, companies’ abilities to serve the new consuming classes often depend on their helping to solve the social problems that impede commercial activity. In large part because of the new wave of globalization, there is a far more powerful connection between business and social impact.

The global ambitions of large companies demand a new approach to social and environmental concerns. In the absence of stable infrastructure in many locations, businesses are working with other stakeholders to find and maintain solutions. While the motivations for attention to social challenges can range from risk mitigation to competitive positioning to achieving market differentiation and growth, a commitment to finding socially based solutions will increasingly be a requirement for success in serving an array of markets. Our exploration of this trend describes the new business imperative and offers examples of businesses that are addressing broader social goals as they pursue success.

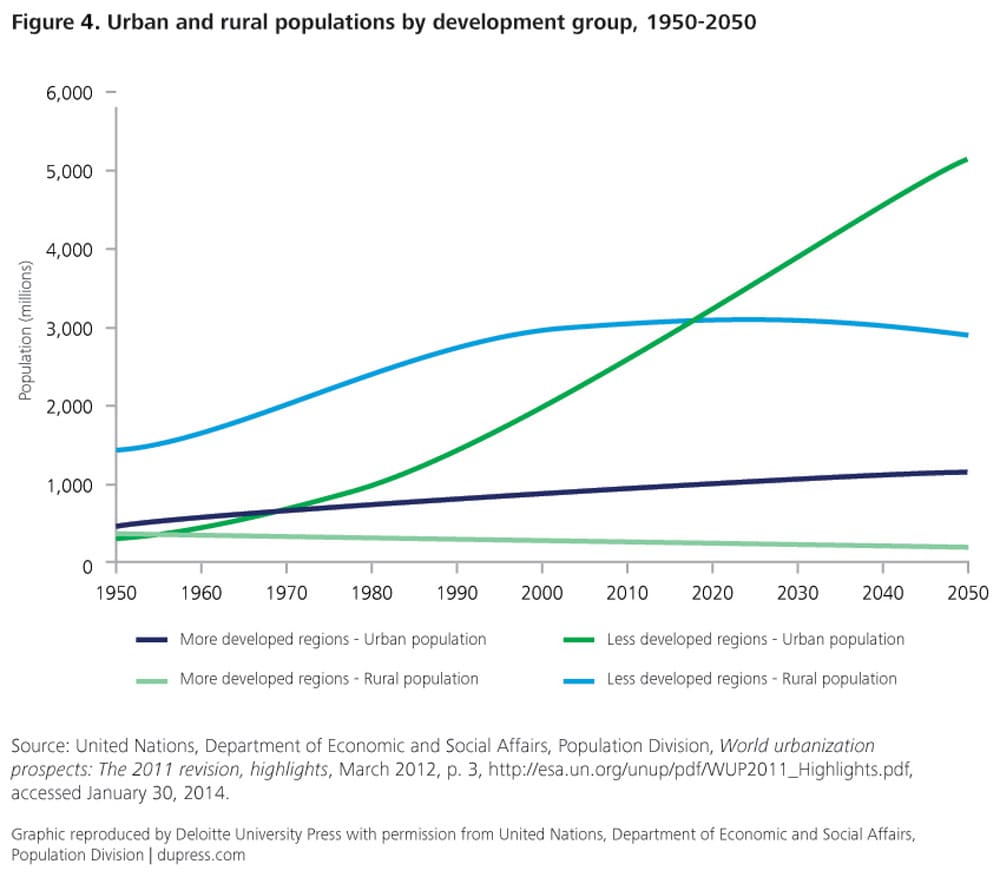

Meanwhile, there is yet another dimension to the dynamic of new consumers. Not only are these new consumers citizens of emerging economies, they are also increasingly urban. Our third trend notes that, today, we exist on a city planet. This creates the need for forward-thinking companies to pay far more attention to their city strategies—because urban areas are so rich in opportunity but so complex and challenging to serve. We are living through the largest wave of urbanization in history, and have already reached the point where the majority of the world’s population lives in urban areas (figure 4).28 (The crossover from mostly nonurban to mostly urban populations occurred in 2009.) By 2030, urban populations will reach almost 5 billion, with growth concentrated in the cities of Asia and Africa. Urban populations are more prosperous; for example, 80 percent of Africa’s total GDP emanates from urban centers, yet currently only 30 percent of the population lives in towns and cities.29

Global megacities such as Shanghai and Mumbai are powerful, recognizable symbols of this urbanization. They are taking their place alongside the long-established global cities of the developed world to exert powerful influence, especially as centers of talent and innovation. However, such vast cities are only part of the new urban story; collectively, they account for less than 10 percent of global city dwellers. It is cities with populations of less than a million that are growing most quickly, and that are home to 60 percent of the world’s urban population.30

Our discussion of these vibrant urban centers emphasizes the need to approach them with multifaceted strategies. Smart business leaders recognize cities as much more than just sources of concentrated and growing demand. They see them as hotbeds of talent and innovation, and as the setting for some of the most interesting and important problems that businesses could help to solve. A promising approach we have observed is the treatment of individual cities as “learning labs,” where strategic engagement can proceed experimentally and yield keys to replicating successes in other locations.

New collaborations

The fast-paced change of today’s business world puts a premium on innovation and agility—and therefore, as many companies have discovered, on collaboration capabilities. In an increasingly interconnected global economy, more businesses will discover the power of looking beyond their own organizations and their familiar markets for the inspiration for their next products and services. They will recognize that the best use of a toolkit they have been using in marketing communications—social media—is actually to connect and collaborate across many areas of the business and with all manner of stakeholders. And, leveraging the richer connections they have made with supply chain partners over the past two decades, they will develop the ability to respond flexibly and efficiently to changes in demand wherever they occur in the world.

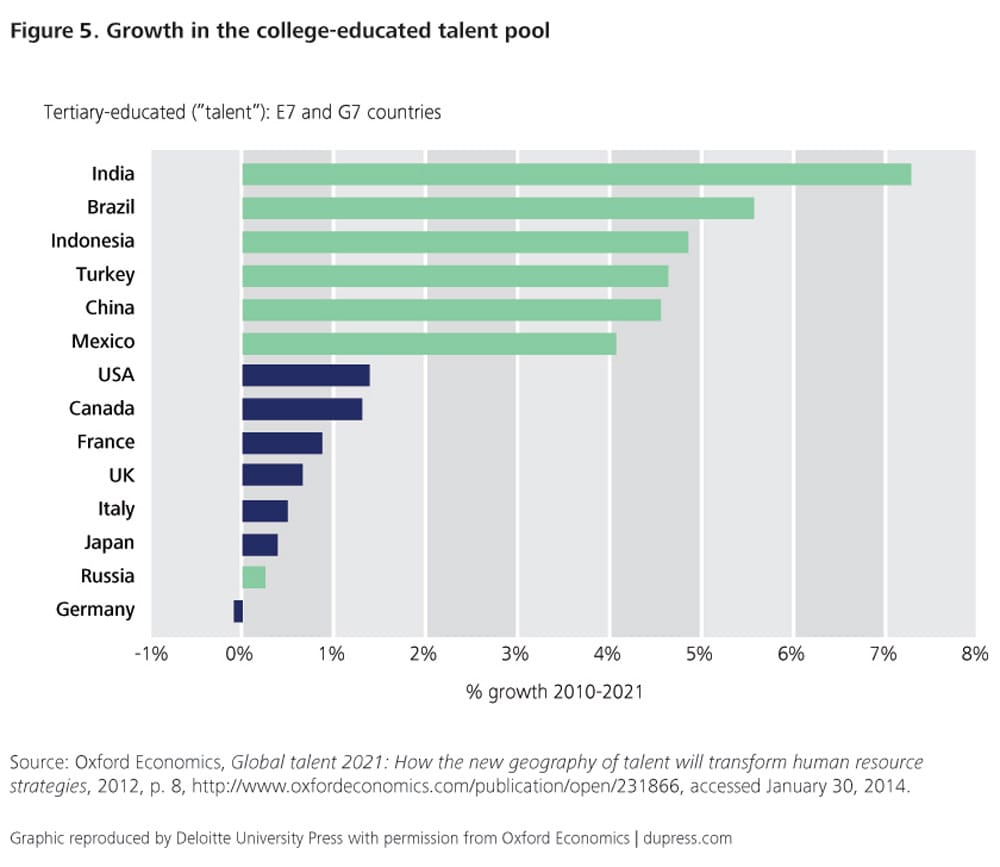

The first of the trends we explore in this section is the fact that, increasingly, innovation happens everywhere. The phrase is true in two senses. First, the Western-centric multinationals that have traditionally developed innovative offerings for their home markets, then adapted them (or didn’t) for foreign customers, are now recognizing the limitations of that approach. We survey how the world of innovation is becoming globally dispersed, broadly moving eastward as a result of the pull of new consumers and new talent. We see the evidence of this in the gleaming new technology parks of Shanghai, and in the research labs multinationals have located in Asia. R&D expenditure in the developing economies grew in their share of the global total from 17 percent to 27 percent between 2002 and 2009.31 Asia’s share of the global researcher population increased from 16 percent in 2003 to 31 percent in 2007, a direct consequence of improving educational output (figure 5).32 While the West might still have advantages in many high-tech fields, emerging markets may promise at least equal dynamism in future years, given the motivation of the population and the lack of legacy systems.

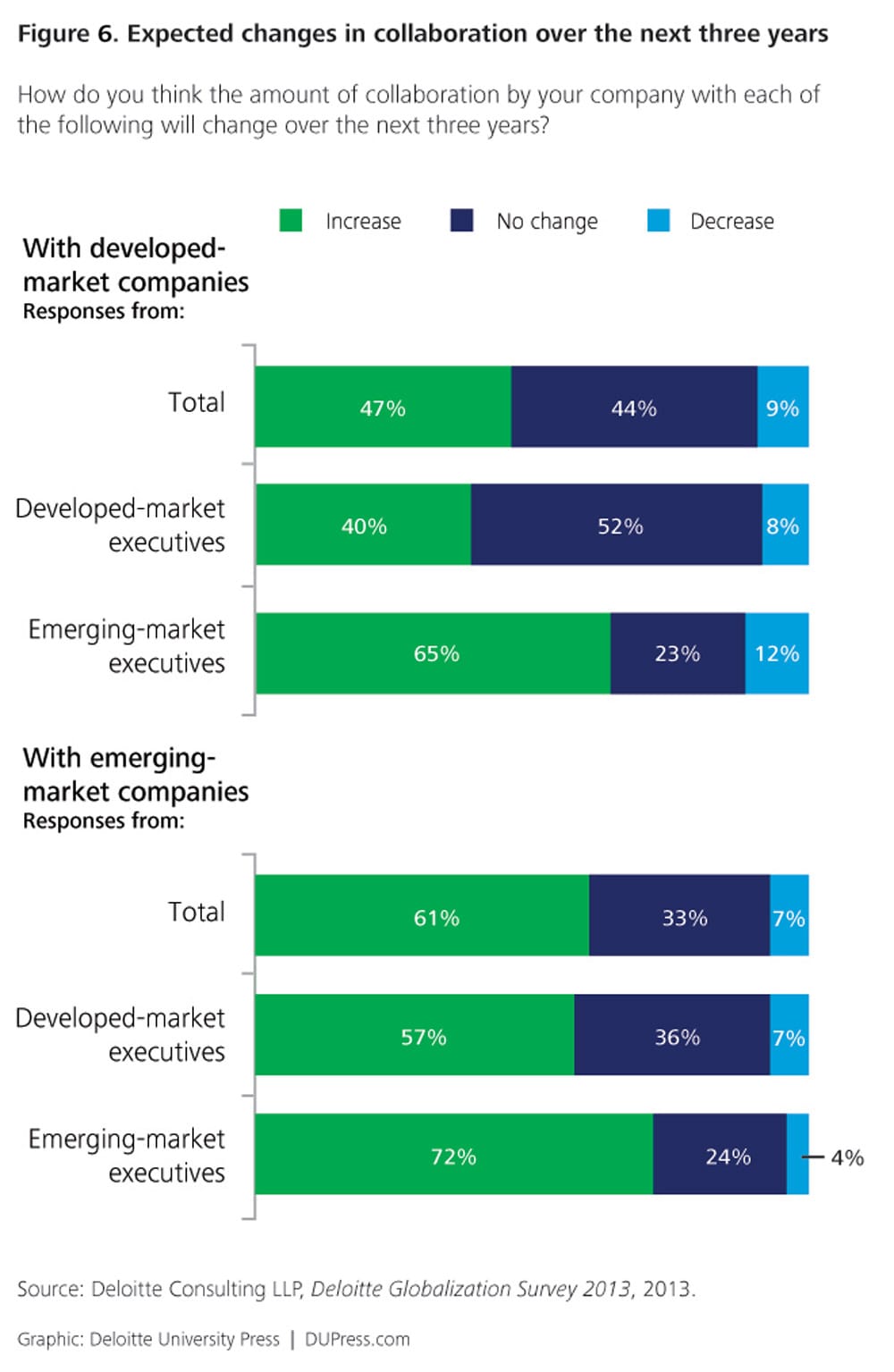

But the second sense in which innovation happens everywhere, and the even more powerful trend, is the shift from reliance on innovators employed by companies and solely devoted to R&D. Today, the whole process of innovation is moving—from “walled gardens” to open spaces, from protecting knowledge stocks to encouraging more collaborative knowledge flows. Interestingly, these two shifts in the locus of innovation seem to fuel each other. In a recent survey by Deloitte of global executives (figure 6), emerging market executives were more likely to state that they anticipated increased collaborative efforts, both with developed market companies (with which 65 percent of emerging market executives expected more collaboration) and with other emerging market companies (with which 72 percent expected more collaboration).33

While a growing attitude of openness to more people, companies, and institutions greatly broadens the range of collaboration opportunities, technology continues to offer the means for such connection and cocreation, within and beyond corporate and national boundaries. These factors combine to create new horizons, in a trend we call social business, global business.

The ongoing increase in high bandwidth connectivity, coupled with a tremendous expansion of highly effective social media technologies, continues to increase collaboration capabilities. Until now, social media has been used mostly by individuals, and the result has been an explosion in growth in the use of social platforms across the world, creating a truly global phenomenon. In the next few years, we expect to see businesses use social media to extend their connections with customers, suppliers, partners, and employees, and to become more globally connected. Our discussion of this trend highlights the ways in which companies are using social technology to maintain a balance between local intimacy and global reach, and hence are becoming more effective global organizations.

There is much progress to be made. In both developed and emerging markets, 61 percent of surveyed executives expected social media to become somewhat or much more important to their business over the next three years.34 As social technologies have evolved, though, they have become much more than simply an advertising platform or a place to connect with consumers. As sophisticated use increases, companies are finding that social media provides benefits in operational efficiencies and collaboration opportunities. The effects may be so profound that it could reshape how we think about organizations in the years to come.35

Global supply chains are critical areas where collaboration and information combine together. They have been central drivers of successful globalization throughout history.

In the chapter on anticipatory supply chains, we describe the changes happening in the world of global supply networks, and the critical role that data, strategy, and collaboration should play in success. In recent years, optimal supply chains were designed, in principle, for standardization and cost-efficiency. But as the next wave of globalization is characterized by change and uncertainty, many businesses are finding their supply chains to be less than fit for purpose. We know that successful global businesses now construct supply arrangements that encourage adaptability and flexibility; supply networks of the future will be designed to anticipate changes and respond to them accordingly. Working seamlessly with partners to develop anticipatory supply chains will require more powerful predictive analytics and a far closer connection with strategy.

New leadership

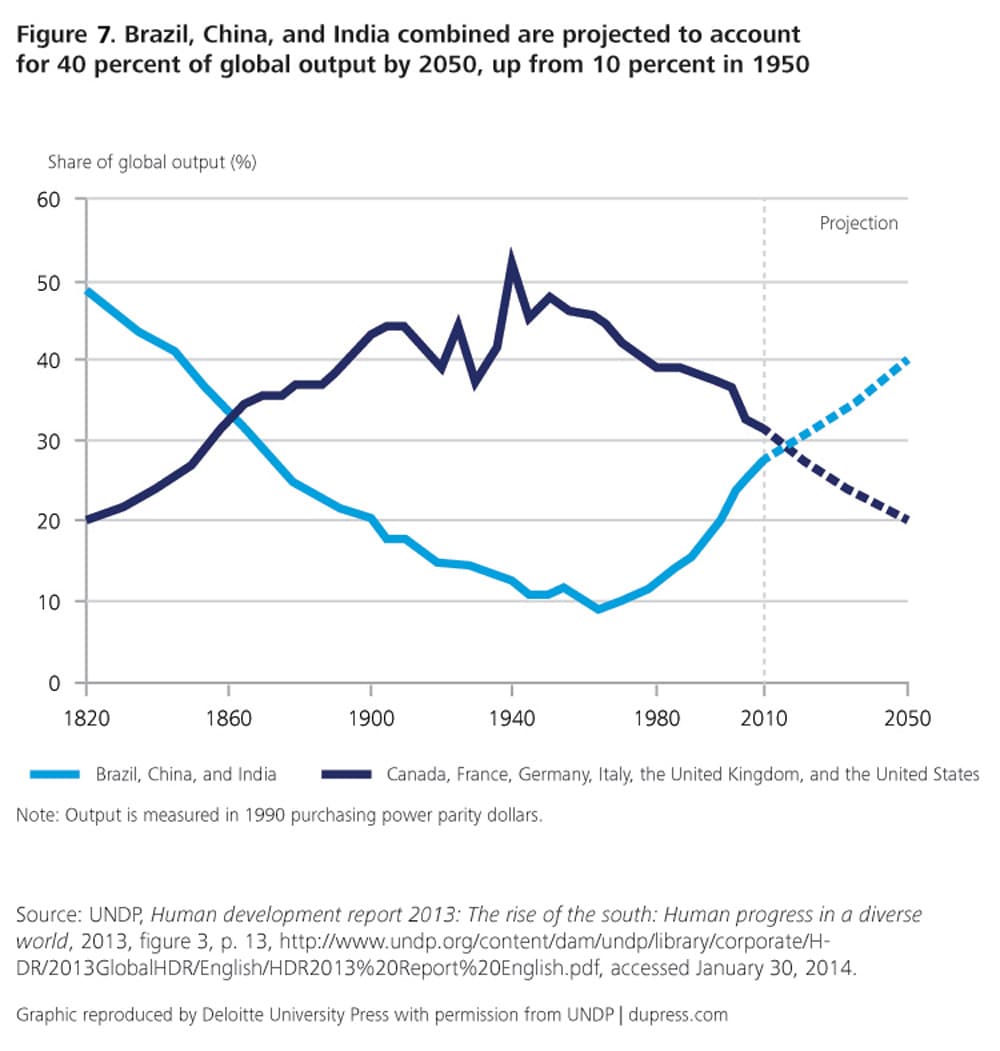

Periods of turmoil, disruption, and uncertainty have been, almost invariably, accompanied by shifts in leadership—of industries and institutions, and at the individual level, by creating new imperatives. The three remaining trends Deloitte highlights for 2014 touch on all these levels. At the level of global industries, we are seeing new organizations emerge as leaders, challenging the influence of established players. The powerful influence of developed economy (and primarily Western) institutions—including corporations—is being eroded. For the first time in 150 years, the combined output of the developing world’s three leading economies—Brazil, China, and India—is about equal to the combined GDP of the long-standing industrial powers of the North—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States (figure 7).36 In the next wave of globalization, leadership and influence—and new business practices—will emerge from new corporate players.

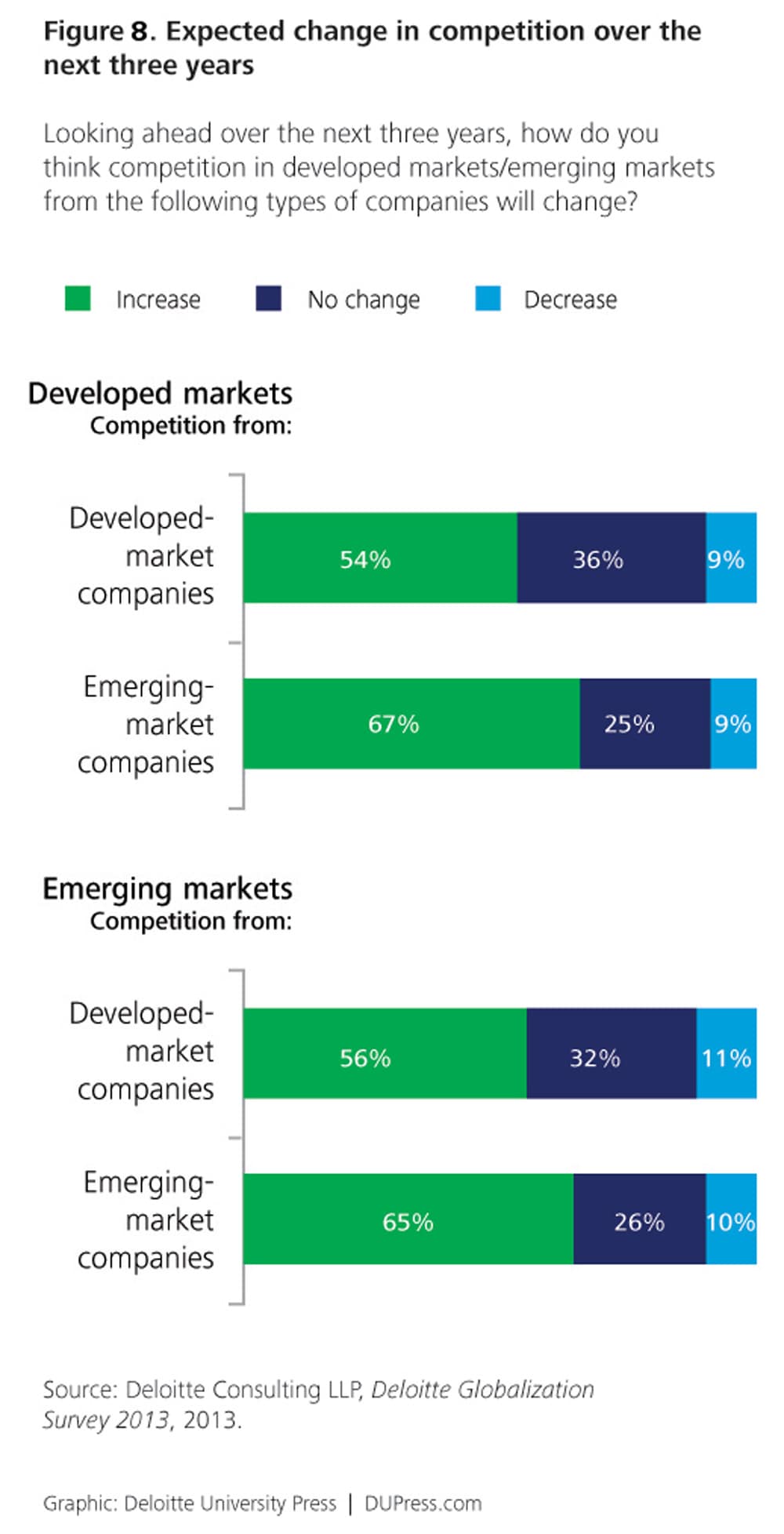

Leadership in the next wave of globalization will be made up of a much more global and diversified group of companies than ever seen before, with much of the ideas and influence emanating from emerging markets. Western corporations have long provided almost unchallenged leadership in most industries—and have in fact created most of them. That is no longer the case. In our survey, over the next three years, business executives expect competition from companies headquartered in emerging markets to become more intense, exerting more of a leadership influence than ever before (figure 8).37

In the chapter on giants, old and new, we describe how “new global giants,” grown from the soil of emerging markets, are gaining the leading capabilities and reach formerly enjoyed almost exclusively by Western multinationals. We expect to see the global business landscape change as companies from very different backgrounds, cultures, and systems compete with each other. The trend outlines the arguments that highlight how new corporate players are becoming globally influential, and also discusses the challenges that these emerging market giants will face. As rivalry becomes more intense, both emerging giants and established players have much to learn from each other as they strive to become truly world-class global organizations.

In quite a difference sense, leadership is transforming for individual business executives, as the changing business scene compels them to shift their attention to new priorities. As the most striking example, the chief financial officer (CFO) becomes the chief frontier officer. One notable consequence of the changing global policy landscape is that we are likely to see divergence in regulatory environments affecting businesses—with implications for tax, audit, capital market, and other finance functions. Thus CFOs of growing global companies are increasingly being called upon to understand and manage a much broader set of business issues than they often oversee in their home or core markets. While the chief executive officer is ultimately accountable for the successful growth of the company, the CFO is often the person to assume the helm of strategic decision making abroad, particularly in emerging economies where little organizational infrastructure is in place. Exploring new frontiers needs the objective, quantitative skillset intrinsic to CFOs. However, CFO roles will often go beyond the traditional market entry analysis to also lead on-site business operational needs.

Our final trend also describes a shift within organizations’ top leadership cadre, but here we argue that the need for change goes beyond changing responsibilities for particular executives. Instead, we ask whether it is time for C-suite version 3.0. This trend explores the composition and role of the group of senior-most executives who routinely convene to chart the strategy of the enterprise and ensure its implementation. Between the mid-1980s and mid-2000s, the size of the C-suite doubled from five to ten, with approximately three-quarters of the increase attributed to functional managers rather than general managers.38 This disaggregation of leadership and decision making along functional lines was appropriate as organizations expanded their reach and influence. However, for this trend we argue that this model might be less suitable for the complex, integrated challenges that lie ahead for global companies. Additionally, we outline the dilemmas that the new model C-suite must master and describe a number of critical new roles that CXOs must play.

****

Welcome to the next wave of globalization. There will be more change to contend with than could possibly fit into one report’s exploration of major trends. We are confident, however, that these nine trends will remain highly relevant for years to come and deserve companies’ strategic attention. The winners in this new age will be inspired by new consumers with new needs, enabled by new collaboration models, and guided by new leadership with a focus on the future.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.