The new calculus of corporate portfolios has been saved

The new calculus of corporate portfolios Part of the Business Trends series

16 April 2015

The rise of business ecosystems is compelling strategists to value assets according to an additional calculus, often generating different conclusions about what should be owned.

Ecosystems are dynamic and co-evolving communities of diverse actors who create new value through increasingly productive and sophisticated models of both collaboration and competition. Read more about our view of business ecosystems in the Introduction.

Ecosystems are dynamic and co-evolving communities of diverse actors who create new value through increasingly productive and sophisticated models of both collaboration and competition. Read more about our view of business ecosystems in the Introduction.

The rise of business ecosystems is compelling strategists to value assets according to an additional calculus, often generating different conclusions about what should be owned.

Overview

EXPLORE

Create and download a custom PDF of the Business Trends 2015 report.

In 2014, a Forbes report on the pending merger of AT&T and DirecTV started with an observation: “A few years ago, the idea of a satellite TV provider merging with a phone company might have seemed weird.” It went on to quote Charlie Ergen, the Dish Network chairman who wanted to buy Sprint just a year earlier:1

We saw the world changing six years ago into several different technologies, right? We had the home covered on a nationwide basis, but there were things such as broadband. There was something called OTT (over-the-top, or TV via Internet Protocol) that was starting to be used around the world, and then there was mobile. And all those things have to come together, and they come together in the ecosystem of communications.

In Ergen’s rationale, there is a key word—one that simultaneously underscores and dispels the weirdness. It’s the word “ecosystem.” That is a term we’re seeing more and more to explain the logic of mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures. From Xerox’s Ursula Burns to Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, many enterprise leaders are strategically reconfiguring their asset portfolios with an eye to the fast-evolving business ecosystems in which their firms are situated. This isn’t just a language change as a trendy metaphor enters the management lexicon. Ecosystem thinking is making strategists value assets differently, and think differently about whether those assets need to be owned.

What’s behind this trend?

Firms have always used mergers and acquisitions to accelerate their entry into new businesses and markets and to build their competitive strengths. Smart management teams approach the question of what to buy and sell as a portfolio exercise in building positions, hedging risks, and looking to maximize capital efficiency. Their rationale for strategic transactions has generally focused on some key goals—quests for synergy, market share, cross-selling, economies of scale, tax advantages, geographical expansion, diversification, and vertical integration. Firms have also always sold assets. Traditionally, the rationale for selling has often been as simple as the need to raise cash or remove the earnings-dilutive effects of a chronically underperforming business. In the modern era, however, deliberations about both M&A and divestiture have become much more complex. Largely due to fast-evolving technologies enabling information flow and communications, the options have proliferated for firms to make productive use of assets with or without owning them. Those options are further energized by enablers like standardization, market transparency, and IP protection which allow ecosystems to take shape, often reconfiguring entire industries as they do. The “transaction costs” that once made it uneconomical to buy many components of one’s offering from outside suppliers have also dropped dramatically. The effect, to use John Hagel’s memorable phrase, has been a long-term trend toward “unbundling the corporation.”2 Today, a management team can decide to produce a specific solution for a specific kind of customer, and then cobble it together with elements procured from specialist firms, with very little capital investment required on their own firm’s part. But by the same token, some management teams find themselves in a newly defensive posture—having to defend why, in that case, they have invested their capital in the assets they have. How do those assets fit with their purported areas of strategic focus? Of all possible owners of a particular part of the business, are they really the owner in whose hands it produces most value? To the extent that management teams do not naturally engage with such questions, they now have a rising chorus of activist investors compelling them to do so. Such investors, who first came on the scene in the 1980s (see the sidebar “Optimizers at the gate”) have a dispassionate view of business units and their owners, and have no reservations about pressuring CEOs to think harder about the cards they hold in their hands, and how to play them. Activists are good at spotting what does not fit—those assets that would likely be more productive in others’ hands. By applying pressure to the disaggregation process, they help keep ecosystems reforming fluidly.

Firms have always used mergers and acquisitions to accelerate their entry into new businesses and markets and to build their competitive strengths. Smart management teams approach the question of what to buy and sell as a portfolio exercise in building positions, hedging risks, and looking to maximize capital efficiency. Their rationale for strategic transactions has generally focused on some key goals—quests for synergy, market share, cross-selling, economies of scale, tax advantages, geographical expansion, diversification, and vertical integration. Firms have also always sold assets. Traditionally, the rationale for selling has often been as simple as the need to raise cash or remove the earnings-dilutive effects of a chronically underperforming business. In the modern era, however, deliberations about both M&A and divestiture have become much more complex. Largely due to fast-evolving technologies enabling information flow and communications, the options have proliferated for firms to make productive use of assets with or without owning them. Those options are further energized by enablers like standardization, market transparency, and IP protection which allow ecosystems to take shape, often reconfiguring entire industries as they do. The “transaction costs” that once made it uneconomical to buy many components of one’s offering from outside suppliers have also dropped dramatically. The effect, to use John Hagel’s memorable phrase, has been a long-term trend toward “unbundling the corporation.”2 Today, a management team can decide to produce a specific solution for a specific kind of customer, and then cobble it together with elements procured from specialist firms, with very little capital investment required on their own firm’s part. But by the same token, some management teams find themselves in a newly defensive posture—having to defend why, in that case, they have invested their capital in the assets they have. How do those assets fit with their purported areas of strategic focus? Of all possible owners of a particular part of the business, are they really the owner in whose hands it produces most value? To the extent that management teams do not naturally engage with such questions, they now have a rising chorus of activist investors compelling them to do so. Such investors, who first came on the scene in the 1980s (see the sidebar “Optimizers at the gate”) have a dispassionate view of business units and their owners, and have no reservations about pressuring CEOs to think harder about the cards they hold in their hands, and how to play them. Activists are good at spotting what does not fit—those assets that would likely be more productive in others’ hands. By applying pressure to the disaggregation process, they help keep ecosystems reforming fluidly.

Optimizers at the gate

As the logic of ecosystems begins to guide more strategic transactions, the rising prominence of activist investors is an accelerant.

Certainly we are seeing pressure from activist investors. Recent data suggests that the success of activism campaigns has more than doubled over the last decade, to the point that more than 70 percent of such campaigns now prompt change.3 Moreover, nearly every senior corporate executive and activist hedge fund manager surveyed in 2014 by the law firm Schulte Roth & Zabel and the data provider Mergermarket stated a belief that activism would rise over the next 12 months. More than half said the increase would be “substantial.”4

Activist investors came on the scene in the 1980s, portrayed mostly as “Barbarians at the Gate”— corporate raiders with an interest in a quick financial return, and little interest in the creation of long-lasting value. This often meant breaking up corporations and selling off the constituent parts. This remains the characterization of activist investors by much of the mainstream media. However, today, there are many more activists claiming a willingness to consider value-creation stories that take time to play out. Jeffrey Ubben of the hedge fund ValueAct Capital Management claims that he and his partners are “patient investors,” and would like to see activism mature into an asset class, like private equity, providing long-term value to companies rather than just giving a quick jolt to activists’ returns.5

A recent survey found that only 16 percent of activist investments were held for less than six months, while 36 percent were held for more than a year.6 In recent months, we see that activist investors have worked in concert with pension funds, which clearly have long-term value as their primary consideration. The California Public Employees Retirement System (Calpers) has “dabbled” in being an active partner with funds,7 while California State Teachers Retirement System urged PepsiCo to put activist investor Nelson Peltz on the board.8

In this sense, it is revealing to think of activist investors as a critical—and natural—element of an ecosystem-focused deal environment. They are interested parties who are willing to think broadly—and sometimes radically and painfully—about the position and assets held by a corporation. They approach opportunities in bigger and more fluid terms than corporate executives because they have a single role: to spot opportunities where shifting an asset from one place to another will deliver greater value. They are facilitators of movement within and between ecosystems.

And now, into these high-stakes considerations of what core businesses, complementary businesses, and other assets firms should hold, a new way of thinking about the commercial environment has been introduced. Many managers have begun to see their competitive environs—and the strategic options available to them—as dynamic and diversely populated ecosystems. Talk of ecosystems—and deals that only made sense in those terms—showed up first in the high-tech clusters of Silicon Valley and Route 128 outside Boston. But this new basis for planning mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures is now seeping into other sectors from health care to industrial manufacturing.

The trend

In the years of weak economic recovery after the 2008–09 financial crisis, corporations were reluctant to invest in major strategic transactions.9 The result was that corporations came to hold substantial piles of cash on balance sheets. By 2014, capital was abundant and inexpensive; and a buoyant US equity market supported the growing sense of confidence among consumers, investors, and executives. Meanwhile, some market worries of previous years—spikes in the euro crisis, concerns over the US debt ceiling—became less prominent. All this set the stage for a return to heated merger activity. The 2014 worldwide deal count, led by activity in technology, media, health care, and energy, was up by 6 percent, and the value of those deals had increased by 47 percent.10 But something else was happening at the same time, at a deeper level. Now that deal activity has picked up, it’s possible to see new and different patterns in the transactions. Many are no longer only about financial engineering, cost-cutting, or straightforward growth, where corporations would stitch new parts on to their organizations to reap the benefits of scale. More deals appear to be done with the dispassionate perspective of the “activist inside.” Again, activist investors are the enforcers in the current M&A landscape and, as much as anything, they use the quantitative logic of capital efficiency to motivate portfolio moves. Their attention, or even just the threat of it, focuses many executives’ minds on how their firms create value as the business landscape changes around them. Indeed, a CEO today who isn’t hyper-focused on where the firm’s value is created (and where it may be destroyed) may quickly find activist investors making the argument for them about what ought to be owned and what ought to be disposed of. So, many leaders tend to cast a keen and constant eye on this equation and make the argument themselves—essentially bringing the activist in-house. Take, for example, Time Inc. chairman Joe Ripp describing his team’s deliberations:

We are in the process of looking at everything that we have today and trying to figure out, are there ways to make them more valuable than they are today? And if not, does selling them or enhancing them or investing in them or partnering them with other people make them more valuable to our shareholders. While we’re not commenting on any one particular asset, we’re willing to sell those things that make no sense for the portfolio and invest in those that do.11

New options for growth

As this newly disciplined thinking spreads, we see firms migrating toward a new calculus for sizing up the available options. Increasingly they are thinking in terms of ecosystem plays. When a leadership team has a different philosophy guiding its portfolio of assets, it makes different choices than it might otherwise have made. Much of the M&A activity today is being guided by business leaders’ points of view on how ecosystems are evolving. Importantly, a management team attuned to the dynamics of ecosystems also sees that some deals don’t have to be done at all. The assets they need are often present in the ecosystem, able to be readily leveraged. Thus, the world of ecosystems is creating a “third pathway” to growth: using strategic alliances in place of transactions or organic growth initiatives. This third pathway allows firms to pursue “leveraged growth”—that is, to secure the use of others’ owned assets to support their own expansion. Pharmaceutical companies, for example, have many years of experience in constructing “global strategic alliances”12—collaborations to help ensure that they get the benefits of growth without the burdens of ownership.

More strategic divestitures

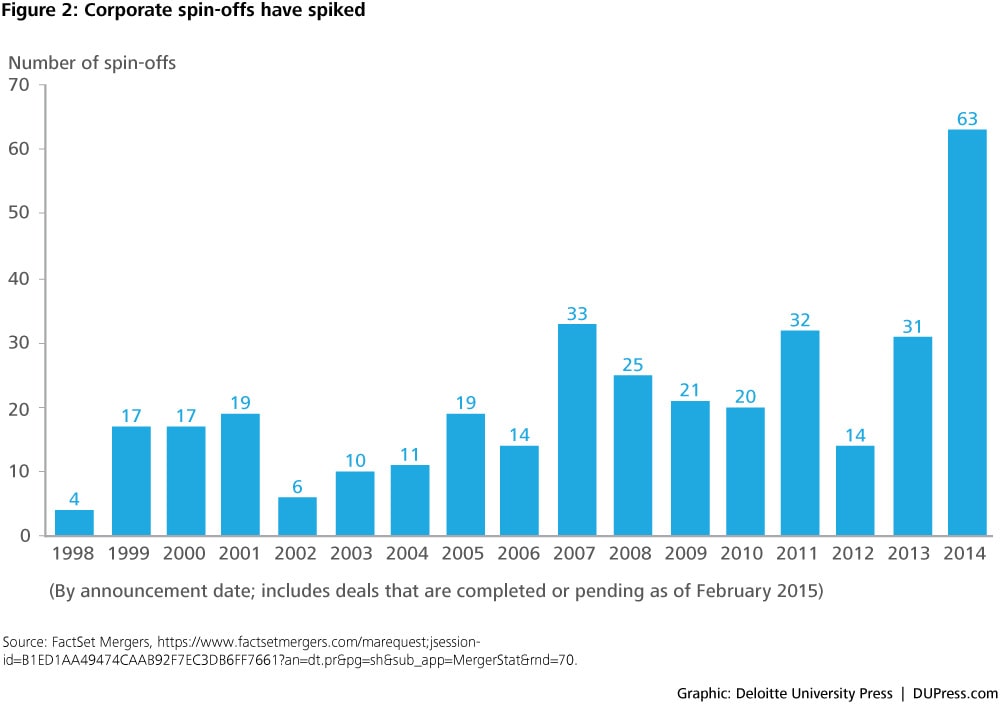

One result of increased activist pressure and ecosystems perspective-taking is a more deliberate and strategic focus on divestitures. Certainly we are seeing strategic separations show up more in the mix of corporate transactions. In 2014, 63 US companies completed or initiated pending spin-offs,13 up from just 31 in 2013.14 That makes 2014 the busiest year for corporate spin-offs since 1998, the first year for which full data is available. The higher numbers reflect higher-level thinking. Divestitures are becoming more strategic, as executives take a common question of activist investors seriously: “Are we really the best owner of this asset?” If a part of the business would be more valuable in someone else’s hands, it may make sense to participate in that higher value by selling it—especially if, thanks to easy transactions within the ecosystem, it can be sold without any real risk to the company’s ability to deliver its offerings.

One might well ask, in a business ecosystem where it is possible to own or not own nearly any asset required to produce a customer offering, what should be the rationale for owning some things and not others? What, to use the economist’s terminology, is the theory of the firm? In response to this fundamental strategic question, we see managers increasingly citing a new or shifting “focus” as the key driver of their strategic transactions. Take Hewlett-Packard, which recently took the bold step of announcing its intention to separate into two companies, HP Inc. and Hewlett Packard Enterprise. In its statement to the business press about the move, HP’s management used the word “focus” and its variants no fewer than a dozen times.15 Media giant Gannett did the same when it announced that it would spin off the business that was its genesis—publishing regional daily newspapers—to allow it to focus on the broadcast and digital media businesses it sees as its future.16 In a recent Deloitte survey, top executives were asked to name the most important reasons behind their recent divestitures. The importance of pruning their business of “non-core assets” landed in the top two reasons for 81 percent of executives, up from 68 percent when the same question was posed in 2010.17 In recent years, GE has broadly moved away from owning assets in clearly defined industries. By divesting NBC, GE Capital, and GE Appliances, it has reset its focus to succeed in one of the largest of all ecosystem plays. As CEO Jeff Immelt states it, “We will lead as the industrial and analytical worlds collide. We believe that every industrial company will become a software company…. We call this the Industrial Internet.”18 Similarly, in life sciences, Bayer divested its plastics business in order to better apply its skills in human, animal, and plant health. It is now focused on working in solution ecosystem spaces, like food security, population, and access to health care.19

Bungee divestitures

In an ecosystem world, a divestiture is also sometimes seen as the way to free a business unit to pursue different opportunities within new ecosystems, or to enhance its positioning within ecosystems that are evolving. This is a recognized trend in the technology space, where firms now prepare more actively for divestitures, with more deliberate operational, financial, and structural planning. And more of these are what we might call “bungee divestitures.” These occur when firms must resolve competing pressures—on the one hand to divest themselves of any assets of which they are not the best owner, and on the other hand to provide more integrated total solutions to customers. Many managers are discovering that one resolution is to do divestures with “strings attached.” The separation also includes an agreement that ensures an ongoing privileged relationship between the formerly joined companies. Seen in this light, eBay’s decision to spin off PayPal as a free-standing business is more than simply an effort to capitalize on PayPal’s stand-alone market valuation. PayPal’s high valuation reflects a faith in the position it will come to occupy as a full and unencumbered player in the newly dynamic payments and payments processing ecosystem. As PayPal CEO John Donahoe puts it: “PayPal is in a position to really be the link between the technology ecosystem and the payment industry.”20 But while PayPal pursues “independent” growth in the payments ecosystem, it will also continue to serve as a critical part of the eBay-centered auction ecosystem.21 Similarly, AMD divested GlobalFoundries to allow the manufacturer to focus on providing high-quality semiconductor fabrication services to any customer. Subsequently, AMD has become one of GF’s largest customers.22 In a world characterized by interconnected ecosystems, expect to see more strategic separations attended by continued ties of this sort.

Implications

Ecosystems are far less stable than industries. They are resilient and enduring, but internally they are characterized by constant flux. There are simultaneous pressures for fragmentation and consolidation.23 Some businesses (especially in media, software, and retail) break up and get smaller, driven by demand for customization and lower barriers to entry. Other industries (think technology infrastructure) move toward fewer, more dominant players, as these large firms provide resources, information, and platforms for fragmented players.

Going forward, corporations will increasingly use strategic transactions to stake out and adjust their positions in dynamic business ecosystems.

One clear implication is that doing M&A and divestitures based on an ecosystem strategy will mean revisiting the portfolio on a more continuous basis. For corporations participating in fast-moving ecosystems, this means that all parts of the business are subject to constant reappraisal. Are they still suitable parts of the portfolio? Ecosystem dynamics can be complex. The roles of different players in an ecosystem can change, sometimes quickly. If this happens, then the logic of holding on to an asset can shift. Besides, coordinating across an ecosystem of several firms is a complex endeavor. For this reason, corporations will sometimes take a minority share in a collaborating business, as this becomes a way to align incentives and interests around an ecosystem. Minority shares also have the value of providing options—which may be vital in a world where ecosystem dynamics can be complex and unpredictable. A minority stake can be sold, and the position readily reversed, if the logic of collaboration weakens. One thing that likely won’t change is the desire to buy into high-growth businesses born of innovation. But veteran dealmakers used to monitoring the lifecycles of industries might find that ecosystems evolve in different ways. When Mark Zuckerberg oversaw Facebook’s 2014 purchase of virtual reality company Oculus, he cast it as “a long-term bet on the future of computing.”24 It is one of Facebook’s efforts to explore the next big platform after mobile. The acquisition might be a ten-year play, but Zuckerberg is already clear about the critical steps: “It’s building the first set of devices and building the audience and the ecosystem around that, until it eventually becomes a business.”25 Similarly, in the fast-evolving space of additive manufacturing (or 3D printing), we see deals being done in line with a vision of how the ecosystem will take shape. When Stratasys (a leader in 3D printing) recently acquired GrabCad (a leading cloud-based CAD collaboration platform and community site),26 David Reis, CEO of Stratasys, explained the strategic logic of the deal: “Future success with our industry will go beyond simply providing the market with best hardware and material solutions. We believe we must develop a leading 3D printing ecosystem.”27 Thus, we should also expect due-diligence reviews of proposed acquisitions to take on new kinds of questions and risks. Now, transactions need to be assessed in terms of more complex ecosystem consequences. Traditionally, a straightforward acquisition has involved a detailed review of the performance of the target business, coupled with an assessment of the future cash flow benefits. But any corporation pursuing an ecosystem strategy may need to conduct more sophisticated assessments, exploring how a new acquisition (or divestment) might affect the health and productivity of an ecosystem and the firm’s position in it. For all these reasons, deliberations about strategic transactions are becoming a more prominent and constant item on top management teams’ strategy agendas. Rather than experience them as occasional, highly distracting, and disruptive events, they must build a competence in managing their asset portfolios fluidly on an ongoing basis. Deal-making itself will perhaps be held just as close to the vest of the CEO. But the strategic scanning of the ecosystem and discussion of where things are going will be a conversation best informed by many perspectives.

What’s next?

Going forward, corporations will increasingly use strategic transactions to stake out and adjust their positions in dynamic business ecosystems. Sometimes they will explore acquisitions to build the platforms that create foundational capabilities for other participants in the ecosystem. Sometimes they will divest assets and focus more tightly on the capabilities they need to succeed in highly focused roles, engaging with other firms via someone else’s platform. To make these decisions effectively, dealmakers will more explicitly study the evolution of ecosystems, especially looking for new ecosystems taking shape. As firm behavior changes around M&A and strategic separations, there will be implications for those outsiders whose business it is to assess or assist with the transactions. The analytic tools to assess ecosystems will likely proliferate and improve. We might well see “ecosystem analysts” arrive on the scene to provide more sophisticated commentary than traditional industry analysts can. Investment experts will value assets differently in light of emerging concepts of ecosystem value. Given the flux inherent in today’s business ecosystems, the frequency of strategic transactions might increase, too. Ecosystem thinking might drive not only a more constant review but also a more frequent reconfiguration of assets and relationships. Many firms will find this stepped-up pace and volume tough to manage. Mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures are expensive and complicated propositions—not least because they generally require some melding together of different corporate cultures and infrastructures. Finally, we expect to see today’s talk of “focus” in the communications around strategic transactions to become more sophisticated as well. In a world where ownership of many assets is less critical, management will be very aware of the signaling power of any acquisitions and sales they make. What does the transaction say about the firm’s point of view on the evolution of the ecosystem? Where does it indicate they will carve out their place? Over time, we may see managers change their attitude toward transactions to believe they are as much about signaling as synergy or scale.

My take

By Peter Shea

Peter Shea has been analyzing asset portfolios for over 30 years as operating partner at Snow Phipps, past president of Icahn Enterprises, and former managing director in Europe for H. J. Heinz Company.

I haven’t heard people in private equity use the term ecosystem a whole lot, but that doesn’t mean they don’t act on the concepts behind the term. As industry lines blur and as economic sectors evolve, the value of assets are constantly shifting. You don’t have to call the emerging opportunity spaces ecosystems to know that they trigger the need to rethink what you own and whether you really should own it.

I haven’t heard people in private equity use the term ecosystem a whole lot, but that doesn’t mean they don’t act on the concepts behind the term. As industry lines blur and as economic sectors evolve, the value of assets are constantly shifting. You don’t have to call the emerging opportunity spaces ecosystems to know that they trigger the need to rethink what you own and whether you really should own it.

Accepting and acting on the consequences of an evolving business environment—or ecosystem as you may say—can be truly difficult for individual executives. No one wants to be the leader who admits that something once considered ‘a winner’ has evolved to become a real financial burden. It’s also hard to be caught in the driver’s seat when an integration effort is labeled a lost cause. These facts can be hard to swallow and sometimes go ignored or denied for long periods, even when the evidence is overwhelming that something no longer fits or perhaps never really did.

Leaders have to constantly be asking the hard questions. Do the businesses I presently operate still make sense in relation to the competitive environment now taking shape? What really is our core business and do the various pieces we have strung together, perhaps over years of building the company, still complement one another in light of today’s market circumstances?

I’d like to hope that we are seeing executives show a growing willingness to engage with those tough questions. Maybe the uptick in corporate spin-offs going on right now is evidence of that. But I still think you see far too many cases of assets being owned and operated by firms which possibly aren’t the best homes for them. Activist investors have been pushing for higher levels of portfolio scrutiny for a long while. They will certainly continue that push as new sectors take shape, industry boundaries blur, and the need to move assets into and out of portfolios shifts with surprising speed.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.