Achieving digital maturity Adapting your company to a changing world

14 July 2017

Findings from the 2017 digital business global executive study and research project

Our third annual study of global digital business, a collaboration with MIT Sloan Management Review, reveals five key practices organizations best able to achieve digital maturity employ—and the lessons all companies can learn from their success.

Learn More

In a hurry? Read a brief version

Take the 2018 Digital Business Survey

Explore the Digital Maturity collection

Read Deloitte Review, issue 22

Create a custom PDF or download Deloitte Review, issue 22

Executive summary

Adapting to increasingly digital market environments and taking advantage of digital technologies to improve operations are important goals for nearly every contemporary business. Yet, few companies appear to be making the fundamental changes their leaders believe are necessary to achieve these goals.

Based on a global survey of more than 3,500 managers and executives and 15 interviews with executives and thought leaders, MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte’s1 third annual study of digital business reveals five key practices of companies that are developing into more mature digital organizations. Their approaches, which may offer valuable lessons for companies that want to improve their own digital efforts, include:

- Implementing systemic changes in how they organize and develop workforces, spur workplace innovation, and cultivate digitally minded cultures and experiences. For example, more than 70% of respondents from digitally maturing companies say their organizations are increasingly organized around cross-functional teams versus only 28% of companies at early stages of digital development. We discuss how this fundamental shift in the way work gets done has significant implications for organizational behavior, corporate culture, talent recruitment, and leadership tactics.

- Playing the long game. Their strategic planning horizons are consistently longer than those of less digitally mature organizations, with nearly 30% looking out five years or more versus only 13% for the least digitally mature organizations. Their digital strategies focus on both technology and core business capabilities. We discuss how linking digital strategies to the company’s core business and focusing on organizational change and flexibility enables companies to adjust to rapidly changing digital environments.

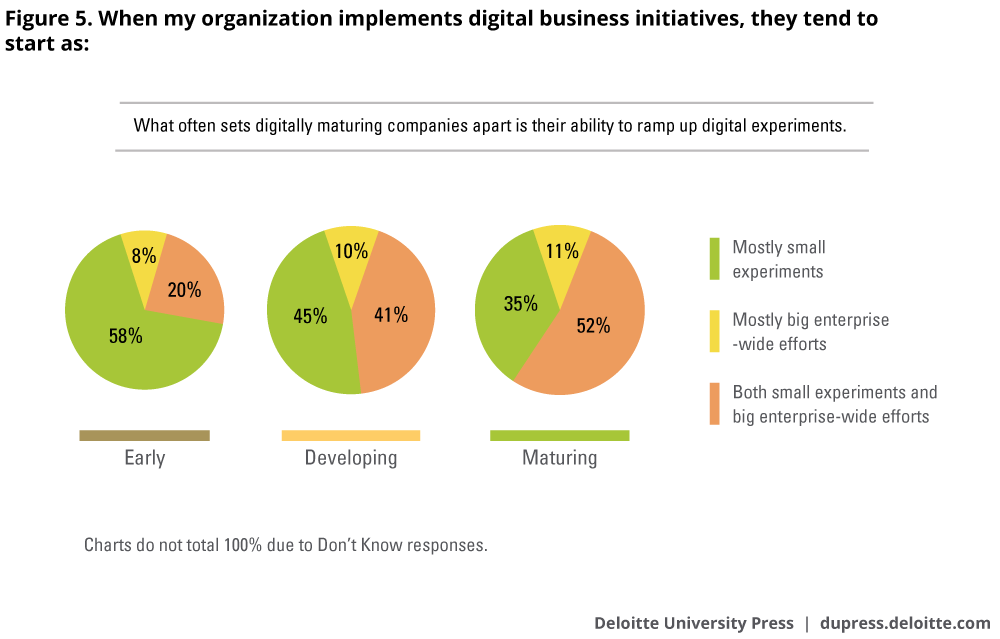

- Scaling small digital experiments into enterprise-wide initiatives that have business impact. At digitally maturing entities, small “i” innovations or experiments typically lead to more big “I” innovations than at other organizations. Digitally maturing organizations are more than twice as likely as companies at the early stages of digital development to drive both small, iterative experiments and enterprise-wide initiatives rather than mainly experiments. Digitally maturing organizations also can be shrewd and disciplined in figuring out how to fund these endeavors and keep them from languishing in the face of more immediate investment needs.

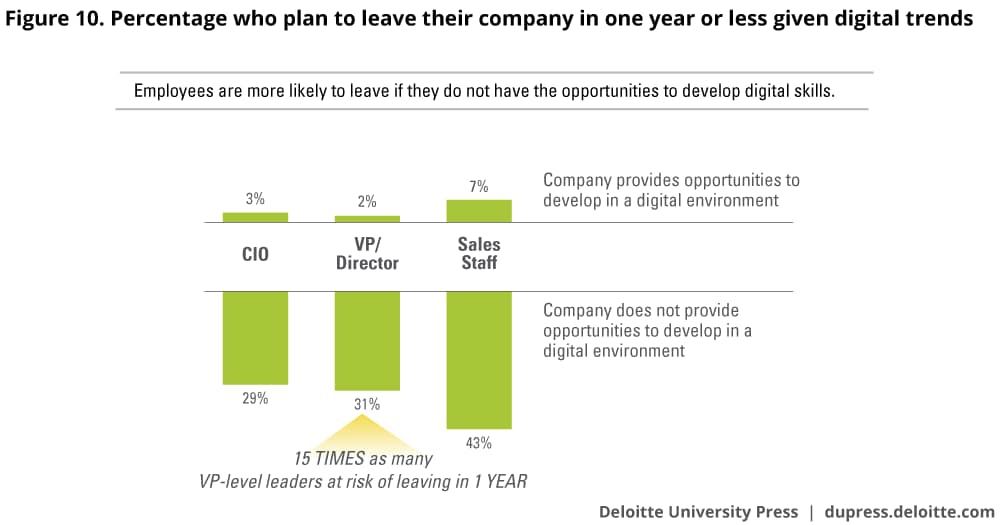

- Becoming talent magnets. Employees and executives are highly inclined to jump ship if they feel they don’t have opportunities to develop digital skills. For example, vice president-level executives without sufficient digital opportunities are 15 times more likely to want to leave within a year than are those with satisfying digital challenges. Digitally maturing organizations typically understand the need for and place a premium on attracting and developing digital talent. Their development efforts often go far beyond traditional training. These businesses create compelling environments for achieving career growth ambitions while acquiring digital skills and experience, which make employees want to stay.

- Securing leaders with the vision necessary to lead a digital strategy, and a willingness to commit resources to achieve this vision. These leaders are more likely to have articulated a compelling ambition for what their digital businesses can be and define digital initiatives as core components to achieving their business strategy. A larger percentage of digitally maturing companies are also planning to increase their digital investment compared to their less digitally mature counterparts, which threatens to widen an already large gap in the level of digital success.

Introduction: Digital maturity and the long game

In 2016, Walmart made headlines by acquiring online retailer Jet.com for more than $3 billion and bolstering that purchase with other e-commerce acquisitions, including Zappos competitor Shoebuy.com, women’s fashion brand Modcloth, and outdoor outfitter Moosejaw. But just a few years before, Walmart began playing the long game and looking at a 10-year horizon of investments, wanting to strengthen its own digital capabilities. Its leaders realized that competing in a digital world demanded more than snapping up leading online retailers to compete with Amazon.com. Walmart is rethinking virtually every aspect of its business to keep pace with changing customer behaviors over the long haul.

First, Walmart is revamping its business strategy. But not just in terms of the next steps it can take today, which the company is doing with everything from developing shopping apps to making investments in frontline training to strengthening its logistics muscle. Instead, the global retailer is creating a digital strategy to address what its leaders believe the company must be able to do 10 years from now. As Jacqui Canney, Walmart’s executive vice president of global people, puts it: “Between the 5- and 10-year mark, people are going to shop in very different ways and expect different experiences. If we don’t work within that time frame, we could be left behind as a customer choice.”

Playing the long game isn’t what Walmart executives dreamed up to challenge the enterprise. It is an intentional response to the changes company executives see emerging in the digital landscape. “Three years is what we can push and move forward,” says Brian Baker, senior vice president of global people. “But over 10 years, we are being pulled by our customers, technology, and globalization.”

In its stores, Walmart has already adapted to change in customer expectations by hiring tens of thousands of workers for new, tech-empowered roles like online grocery personal shopper and self-checkout host.

Achieving its vision of a digital future likely requires the company to work in fundamentally different ways. Enterprises need talent, organizational structure, and culture to be in sync with digital environments around them. “Not everybody sees digital as changing the way you work,” says Canney. “It’s an education to teach people that it’s not really just about technology.”

Walmart is pursuing a score of non-technical, operational changes across the organization to prepare for this digital future. The company is bringing digital talent skills to the entire organization, including a customer-first mindset, collaboration, and design thinking.

The company is also changing how it organizes its employees, encouraging them to collaborate across organizational boundaries. “We are purposefully creating ‘collisions’ between associates who work on projects but who might not have worked together previously,” says Canney. “That is helping accelerate results because people who have different backgrounds and come from different countries are now working together on common problems.”

The above changes are also an integral part of executive job descriptions. “Metrics and objectives focused on digitizing the businesses are now in each of the executive communities for this year,” says Canney. “This year, we’re actually adding digital leadership as one of the competencies for leaders and calling out specifically that this is a new competency they must have in order to be promoted.”

Changes of this magnitude are often destined to fail or stagnate without considerable support from an organization’s leadership. Walmart has support from its CEO, board, and key investors for its digital endeavors.

Walmart is an example of the findings from the 2017 MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte study of digital transformation across industries. This report marks the culmination of our third year exploring how companies do business differently because of digital technology. We continue to probe beneath the surface to find fundamental differences between those who are succeeding with digital change and those who are struggling with it.

Through a global survey of more than 3,500 executives, managers, and analysts, the study finds that companies having some of the greatest success with technology are those that track how their customers, partners, leaders, employees, and competitors are using digital technologies and change how they do business accordingly. Although technology is an important part of the story, it certainly isn’t everything. It may not even play a starring role. Many companies understand technology yet struggle to derive business advantage from it through needed changes to talent, culture, and organizational structure.

Walmart’s approach is indicative of what we are calling digital maturity—how organizations systematically prepare to adapt consistently to ongoing digital change. Digital maturity draws on a psychological definition of “maturity” that is based upon a learned ability to respond to the environment in an appropriate manner.2

Digital maturity is about adapting the organization to compete effectively in an increasingly digital environment. Maturity goes far beyond simply implementing new technology by aligning the company’s strategy, workforce, culture, technology, and structure to meet the digital expectations of customers, employees, and partners. Digital maturity is, therefore, a continuous and ongoing process of adaptation to a changing digital landscape. For that reason, we intentionally use the term “maturing” instead of “mature” to describe the most advanced companies we study.

What sets digitally maturing companies apart

Which companies are digitally maturing, and what can other organizations do to keep pace? To identify digitally maturing organizations, we asked business leaders to “imagine an ideal organization transformed by digital technologies and capabilities that improve processes, engage talent across the organization, and drive new value-generating business models.” (See “About the research.”)

We then asked respondents to rate their company against that ideal on a scale of 1 to 10. Respondents fell into three groups: companies at the early stages of digital development (rating of 1-3 on a 10-point scale, 34% of respondents), digitally developing companies (rating of 4-6, 41% of respondents), and businesses that are digitally maturing (rating of 7-10, 25% of respondents). (See figure 1.)

Across all levels of maturity, the vast majority of business leaders believe in the importance of digital business. Approximately 85% of respondents agree that “being a digital business is important for the success of my company.”

But progress toward that ideal is a different matter. During the three years of our study, the proportion of each group stayed much the same. That consistency may indicate that companies are not advancing digitally—but it could also signal that, amid the rising tide of digital change, many businesses are simply treading water as new digital capabilities emerge to change the definition of the “ideal” digital organization.

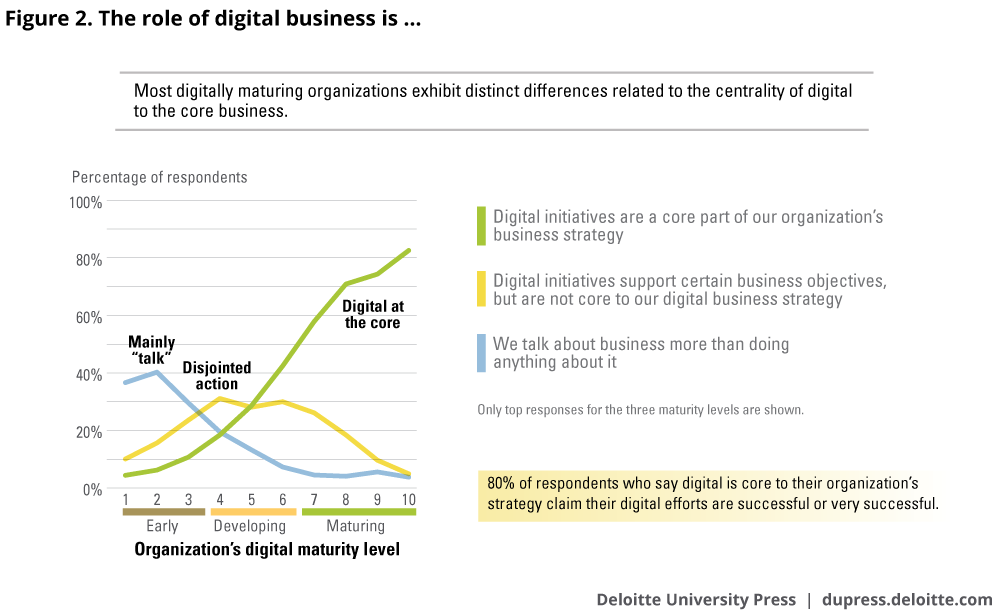

The key issue, however, is how seriously companies go about becoming more digitally mature. Compared to their less digitally mature counterparts, most digitally maturing organizations exhibit distinct differences related to the centrality of digital to the core business.

For example, some 34% of respondents from organizations at early stages of digital maturity say that their company spends more time talking about digital business than acting on it. Although developing stage companies use digital initiatives to support certain business objectives, these efforts may not be core to the business strategy. For digitally maturing companies, on the other hand, the vast majority of respondents say that the company’s digital initiatives are core to their business. (See figure 2.)

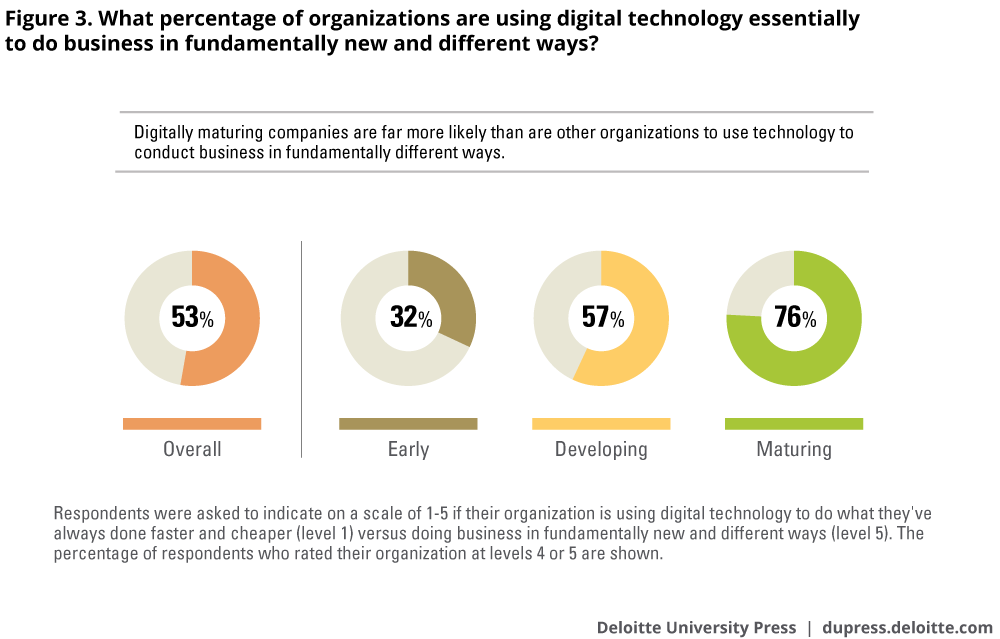

Digitally maturing companies are also far more likely than are other organizations—76% of digitally maturing companies versus 32% of businesses at early stages of digital development—to use technology to conduct business in fundamentally different ways. For digitally maturing organizations, technology typically is not simply an add-on to existing processes and practices. Instead, it prompts these companies to rethink how they do business. (See figure 3.)

The distinctive qualities of digitally maturing companies don’t end here. These companies often tackle strategy, talent, organizational structure, culture, innovation, and technology differently than the rest of the pack. As executives we interviewed often point out, selecting and developing strong leadership is paramount. But most important, digitally maturing organizations have a formidable approach to digital strategy.

A digital lens on business strategy

Our studies consistently find that strategy is the strongest differentiator of digitally maturing companies, which are more than four times as likely to have a clear and coherent digital strategy in place as early-stage companies—80% of digitally maturing organizations versus 19% of companies at early stages of development.3 Digitally maturing organizations also take a longer view on digital strategy: They are twice as likely as early-stage companies to develop these strategies with time horizons of five years or more.

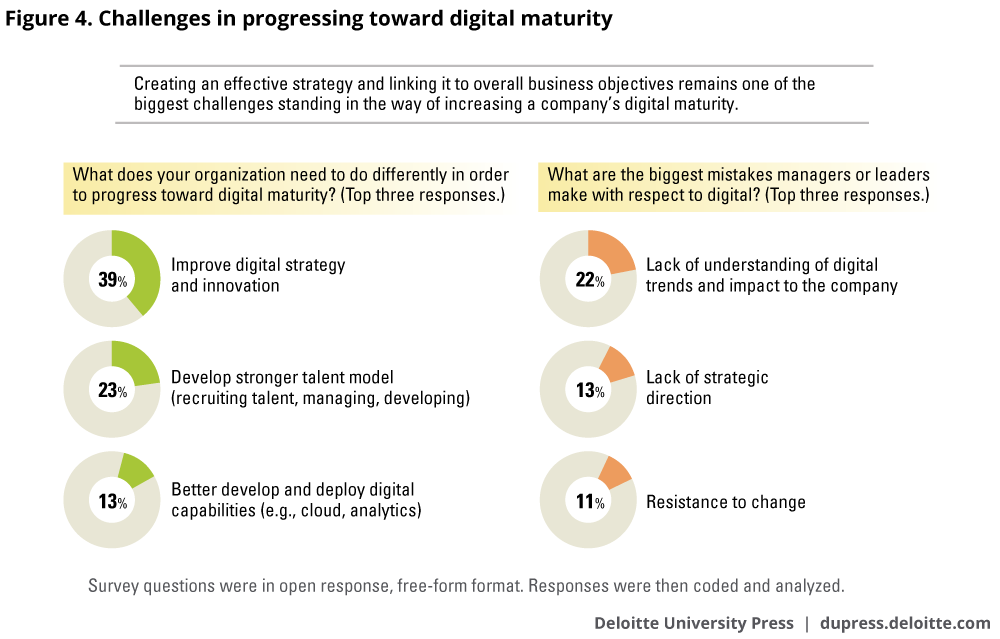

However, creating an effective strategy and linking it to overall business objectives remains one of the biggest challenges standing in the way of increasing a company’s digital maturity. When asked in an open-ended question what their organizations need to do differently in order to advance their digital maturity, nearly 40% of respondents say their company needs to improve digital strategy and innovation. Only 13% report that improving technology development and deployment is a source of concern.

When asked about the biggest mistake managers make with digital business, strategy is again front and center: A weak understanding of digital trends and a lack of strategic direction are the two largest criticisms of managers. (See figure 4.)

Digital strategies aren’t limited to technological issues such as using mobile or migrating to the cloud. Instead, they chart how the organization can and should do business differently as digital technologies change the market. (See “MetLife’s Digital Lens on Business Strategy.”) David Cotteleer, vice president and chief information officer at Harley-Davidson, describes the difference: “Everybody is always talking about digital. But that is not about creating a digital strategy for the company. It is really looking at our business through a digital lens to find where technology could really change our dynamics.” Effective digital strategies are not about implementing technologies for the sake of becoming more digital, but they involve identifying the opportunity for greatest business impact.

Effectively executing a digital strategy requires a focus on organizational change and creating flexibility in order to adjust to rapidly changing digital environments. Volvo is a case in point. The company’s leaders understood that the carmaker needed to not only redesign its cars, but also make fundamental changes in how it approaches innovation, design, collaboration with partners, and governance. The changes yielded a connected car with flexible digital platforms that can accommodate new applications and other enhancements after the owner buys the car.4 Volvo’s digital strategy tackles how the company needs to change its leaders’ mindsets and how its workforce evolves while supporting its core business of building cars—a double challenge that many early-stage digital companies may find familiar.

The importance of putting digital technology into the service of business strategy rather than the other way around is growing to the point that several executives we interviewed actually avoid using digital terminology. “It sounds like the catchy new phrase, and there are people who react poorly to that,” says Christine Halberstadt, vice president, servicer and client management, multifamily, at Freddie Mac. “People should speak in words that resonate. There is strong support on the part of our management team for digital transformation. But I don’t think they’d use that phrase.” An executive at another organization went so far as to quip that his organization feels it has to “trick” its employees into embracing digital transformation by couching it in non-digital language.

MetLife’s digital lens on business strategy

A global financial services company facing intense competitive pressure from its global peers and fintech upstarts, MetLife develops strategies that address the financial services it provides and then looks at how digital technology can make them more competitive.

“There are four pillars that make up MetLife’s strategy—which aren’t of and in themselves digital,” says Martin Lippert, executive vice president and head of global technology and operations. “The first is optimizing value and risk. The second is delivering the right solutions for the right customers. The third is strengthening our distribution advantage. And the fourth is driving operational excellence.”

Lippert wants the organization to think of these pillars with a digital mindset in order to improve the customer experience and make the organization as efficient and effective as possible. As he puts it: “Digital sits in the middle of these four pillars and brings them all together.”

To imbue the company with a digital mindset, Lippert works both top down and bottom up. To strengthen digital thinking on the part of senior management, he recently took several top executives and other senior leaders to Silicon Valley to meet with venture capital executives in whose companies MetLife has invested. The company has also partnered with technology companies, startups, and universities to bring new ideas and approaches into executive offices.

To drive ideas from the bottom up, MetLife hosts an annual event called MetLife Ignition. At the company-wide gathering, portfolio companies from the venture capital companies in which MetLife invested present ideas to employees, including the challenges the innovations address. The event stimulates many new ideas that often move into proof-of-concept and, if preliminary results hold, are eventually rolled out globally.

Digital innovation: More than just experimentation

The vast majority of organizations across the digital maturity spectrum experiment with technology. For example, Cardinal Health has embraced lean and agile approaches to add vigor to its experimentation process. “We use techniques that mirror Google’s one-week sprints,” says Brent Stutz, senior vice president of commercial technologies and chief technology officer of Fuse at Cardinal Health. “For example, we experiment with our customers running week-long innovation and design sessions at their location.”

The scope and scale of experiments, however, don’t always yield results with enterprise-level impact. What often sets digitally maturing companies apart is their ability to ramp up digital experiments. While much is made of the mantra to “fail fast,” deciding what to do when experiments succeed can be a much bigger challenge. “Every large company has an innovation lab here in Silicon Valley,” says John Hagel, co-chairman of Deloitte’s Center for the Edge. “They will always point to those innovation labs as evidence that they are embracing technology creatively. But most are just outposts and have very little impact on the core business.”

One executive describes the challenge in terms of “small i” innovation (experimental efforts) and “big I” innovation (enterprise-wide efforts). Senior leaders at this organization think about the most pressing business problems and what experiments would drive innovations with a “big I.” They then conduct smaller experiments to figure out how innovations with a “small i” can lead to bigger change.

At digitally maturing entities, “small i” experiments lead to more “big I” innovations than at other organizations. As Figure 5 shows, digitally maturing businesses are 2.5 times more likely than early-stage companies to be conducting both small experiments and large enterprise-wide initiatives.

A tolerance for failures and the ability to learn from them underpins the ability to ramp up “small i” experiments. Cardinal Health, for example, regularly kills initiatives and reports on the casualties. “I’m not afraid to create a slide that describes 42 failures and four successes,” says Stutz. “The sooner we stop working on an idea that isn’t panning out, the faster we can move on to the next, better solution.”

Funding innovation

A key challenge to playing the long game is finding resources to move digital initiatives forward while tending to the existing business. Scaling successful initiatives can be accomplished in a number of different ways. While many companies rely on capital investment coming from leadership, other companies are finding new creative ways to fund growth.

For example, many companies are finding investment capital through shrewdness and discipline. At Marriott International, for example, George Corbin, senior vice president of digital, says that some of the company’s most important innovations are its funding models. “Finding ways that we can make a growth opportunity become self-financing is critical,” he says. “If I can do that, the digital opportunity can stand on its own two feet, and scale sustainably.”

MetLife is another example. To fund its digital forays, the company relies on operating profit. “Our CEO said that we needed to become a digital business but had to fund the investment out of expense reductions,” says Martin Lippert, executive vice president and head of global technology and operations. “We agreed early on that for every three dollars of expenses the company can save, two dollars will be reinvested in digital efforts. We have been using this process for three or four years, and we’re investing up to $300 million a year to modernize our foundation and leapfrog the industry with good returns.”

Organizing for digital maturity

Organizational structures based on traditional command and control systems may be impeding the agility needed to operate in fast-paced markets. Nearly 60% of respondents from early-stage companies say that their management structure and practices, which include leadership and decision rights, interfere with their organizations’ ability to engage in digital business successfully. (See figure 6.) In contrast, last year’s study found that 80% of respondents from digitally maturing organizations say their leaders have sufficient knowledge and ability to lead the company’s digital strategy.5 In addition, digitally maturing companies are far less likely than others to rely on hierarchical management structures to make decisions.

The need for cross-functional collaboration

Breaking down functional silos and focusing on cross-functional collaboration is considered crucial to success in digital environments. More than 70% of digital maturing businesses are using cross-functional teams to organize work and charging them with implementing digital business priorities. This compares to less than 30% for early-stage organizations. In addition, respondents from digitally maturing companies are far less likely to say that organizational structures are a barrier to successful digital business.

To some degree, the drive toward cross-functional teams is inherent in how digital technologies change how work is done. “It’s just more difficult to think about any function in isolation because the processes are becoming so integrated,” says David Cotteleer at Harley-Davidson. “The opportunity for integration and collaboration is so great that it drives greater effectiveness and efficiency.”

As an example, Cotteleer points out that connected vehicles demand a stringent cross-functional approach to design and manufacture. “It’s no longer just about product engineering,” he says. “It is about software design, system integration, and other elements that fall outside traditional product engineering. Multiple functions in the company are now realizing that what used to be their domain is now also a domain of technology.”

Improving digitally enabled customer experiences also drives an increasing use of cross-functional teams. A leader at one organization noted that his teams may eventually dissolve boundaries between business units and P&Ls. As digital platforms allow customers to approach the company’s product line as a coherent whole, the company will likely need to reorganize in order to meet these customers’ needs effectively.

Cross-functional teams also encourage employees to think differently. “People have been focused on business capability delivery but just within particular segments of the business,” says Halberstadt of Freddie Mac. “Until you have a cross-functional view, you can’t ask people to think differently.” (See sidebar, “Cross-functional hospitality at Marriott.”)

The importance of working cross-functionally has become so important at MetLife that the company is training its hiring managers in behavioral-based interviewing skills to ensure that new hires have the requisite cross-functional abilities needed to get work done.

Cross-functional hospitality at Marriott

When George Corbin, Marriott’s senior vice president of digital, tried some competitors’ apps, he found that although they worked well technically, they didn’t deliver—he wasn’t checked in when he arrived and he never received the dinner he ordered.

The experience sparked an important realization: “We can create the best website on the planet and we can build the best search campaigns to reach customers,” he says. “But if we can’t deliver an exceptional stay, guests won’t come back.”

To tackle the guest experience head-on, Corbin began working closely with his counterparts in operations and, as he recalls, spent more time with them than with his own team. Corbin made good use of the operational knowledge and has been able to mobilize ground forces to make sure that Marriott’s apps deliver on their promises.

Cross-functional teaming has become a permanent fixture. Multiple functions at the global hotelier now have the same performance metrics including operational effectiveness and costs. There are also digital professionals in almost every function, not just the digital units. “We all work with the same scorecard and address issues together,” he says. “The company takes it seriously. A number of our metrics are reported all the way up to the CEO.”

Technology can spur collaboration and help overcome the common barriers of functional silos. For example, one life sciences company is combining collaboration software and artificial intelligence tools to monitor what its research scientists browse online; connect like-minded scientists; and expedite early-stage drug discovery among the 6,000 researchers in its research division.

Individual functions or departments can also drive collaboration. At CarMax, IT teams host weekly open houses for the entire company that the CEO and other senior leaders of the company often attend. “The open houses foster a tremendous amount of openness and cross-communication that we didn’t have before,” says CarMax chief information officer and senior vice president Shamim Mohammad. “It also shows our teams that we support them. If the senior executive team takes time from their busy schedules to attend these open houses every week (which often last over an hour), that means it’s important to the company.”

Collaboration at some companies moves beyond the organization itself. Cardinal Health, for example, established its Fuse innovation lab to bring together physicians, patients, pharmacists, and providers. These ecosystem partners work with Cardinal Health innovators to deeply understand issues, craft solutions, and try them out. Stutz recalls being in the lab recently and seeing one of the Cardinal Health developers in scrubs because he was shadowing clinicians at a local hospital. “It’s not just about bringing people in,” Stutz notes. “It is about getting them out and observing.”

Digital cultures—collaborative and risk-tolerant

Corporate cultures shift with the transition from siloed operations to cross-functional teamwork. Shared goals and incentives that make cross-functional teaming effective also influence employee mindsets by exposing them to new ways of engaging each other. New mindsets and working styles, in turn, strengthen the company culture and boost its agility. (See “Cardinal Health: Collaboration ‘fuses’ innovation and culture.”).

Cardinal Health: Collaboration ‘fuses’ innovation and culture

Cardinal Health, a global, integrated health care services and products company, enhanced its culture by establishing (in 2014) a new innovation center called Fuse. The Fuse team is housed 2 miles away from corporate headquarters in Dublin, Ohio, and places a premium on cross-functional work.

Cross-functional teams, including Cardinal Health engineers, creative designers, and scientists, work alongside pharmacy customers, health care providers, and other ecosystem participants. Customers and employees regularly propose ideas that are screened and tested using agile one-week sprints.

Innovation centers can sometimes be thought of as outposts that are disconnected to the overall company. Continued support from Cardinal Health’s leaders helps ensure that Fuse initiatives are integrated successfully into the broader organization. “Senior leadership came with the idea of Fuse, supports it, and talks about it,” says Brent Stutz, senior vice president of commercial technologies and chief technology officer of Fuse at Cardinal Health. “Without that, I’m not sure we would have the buy-in or the engagement from the rest of the organization or even from our customers.”

Stutz stresses that maintaining (rather than just building) a digitally supportive culture is critical. Supporting collaboration can be one of the more demanding challenges. Collaboration needs the right talent. When it comes to hiring for and building a digitally supportive culture, Stutz looks for characteristics such as empathy, problem-solving ability, curiosity, and adaptability. As he puts it, “It’s not always the smartest person we hire, but the person who is going to be the team player and bring a genuine passion and energy for solving big problems.”

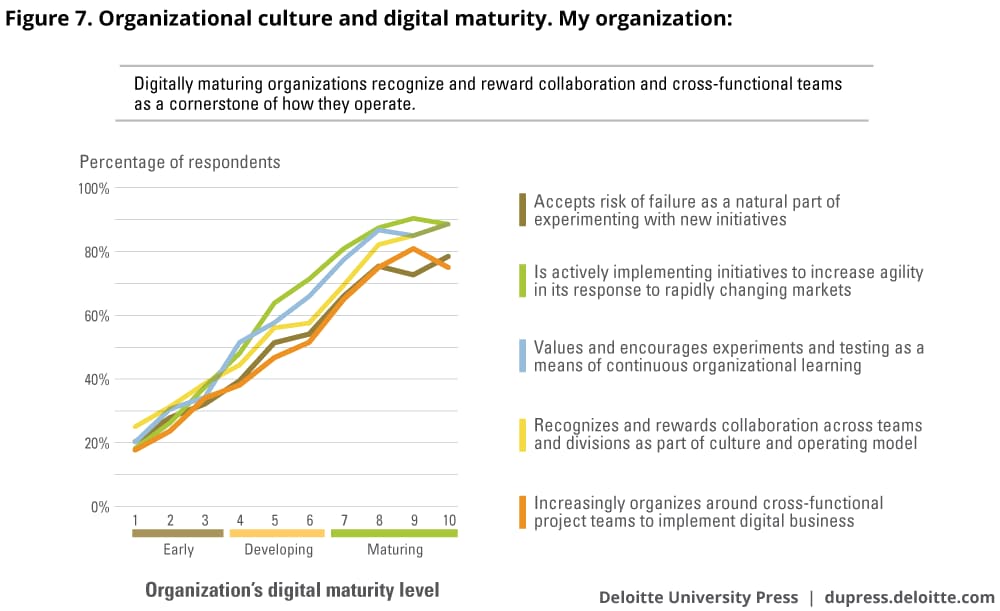

Thus, digitally maturing organizations recognize and reward collaboration and cross-functional teams as a cornerstone of how they operate—nearly 77% of digitally maturing entities versus 34% of early-stage entities. Approximately 85% of digitally maturing organizations place a premium on initiatives that drive organizational agility. Among their early-stage counterparts, far fewer (30%) express the same value.

Overcoming aversion to risk is perhaps the most important characteristic of digitally maturing cultures. They have conquered this cultural barrier by encouraging their organizations to experiment and accept the risk of failure—approximately 71% of digitally maturing organizations versus some 29% of early-stage companies. (See figure 7.)

Although leaders need to cultivate the right culture to achieve digital maturity, digital maturity also drives the culture and its most important traits. Early-stage companies, for example, often attempt to drive digital business adoption through senior management mandates. Developing companies have progressed to the point that they expect employees to embrace digital business opportunities. Digitally maturing companies, however, intentionally cultivate their digital cultures in support of critical business initiatives. (See figure 8.) In our previous research, we found that digitally maturing companies were more likely than less digitally mature companies to take active steps to improve their digital culture further.6 These combined observations suggest the development of a virtuous circle where digital maturity spurs change by increasing adoption of digital business and vice versa.

Invest in digital talent: Use it or lose it

Digitally maturing organizations are far more confident than are others about having sufficient digital talent in their workforce. (See figure 9.) To develop and hold onto that talent, developing it needs to go far beyond training to creating an environment where employees are eager to continuously learn, gain digital experiences, and grow. “Firms are focused on creating the types of environment where workers can continuously learn,” says Prasanna Tambe, associate professor of information, operations, and management sciences at New York University. “They create environments where workers like to spend time.” (See “Unleashing learning at Cigna.”)

Unleashing learning at Cigna

Cigna, the global health care services company, has made learning a priority for not only its leaders and employees but also for health care professionals, sales brokers, and consumers to help keep them healthy.

Part of the equation is formal education initiatives both inside and outside the organization. The company has calculated that its investments in reimbursements to employees to pursue relevant degrees and professional programs have ROIs ranging from 129% to 144%. Employees who participate in these programs are also up to eight times more likely than others to be promoted, given stretch assignments, and be retained.

Yet, Cigna does not adopt a laissez-faire approach to these initiatives. As part of the company’s strategic planning, it determines which skill sets will be most important. Cigna then offers employees three times the tuition reimbursement allowance for key strategic skills it has determined will be critical in the coming years.

Cigna’s efforts also go beyond traditional training initiatives. A key principle in finding the right solution is to meet users where they are. One of chief learning officer Karen Kocher’s first major initiatives was implementing a collaboration platform to stimulate ongoing learning. When the company rolled it out, it discovered that users wanted it to include all relevant information about their jobs and roles. To meet users where they are, Cigna put its performance management system on the platform. Now, users consult the platform for the information they need but remain there to collaborate with others. “We had to figure out what people wanted to learn in a social context,” says Kocher. “We need to be there when they need something in order to sustain the collaborative learning.”

To make work a place where people want to learn, Tambe observes that many companies are encouraging employees to participate in platforms and communities where they can share ideas with and learn new skills from experts in other organizations. Instead of asking staff members to be secretive about their work, some businesses encourage them to be active on platforms such as GitHub, where they can collaborate on the development of cutting-edge technologies with experts in other organizations. This can help attract the types of workers who want to be able to learn about the newest technologies, and some of the skills and knowledge gained by working on these projects can directly benefit their employers.

Although working on open-source platforms allows other companies to experience an employee’s capabilities and poach them, environments that stimulate learning are more likely to retain talent. “We’ve changed how we look at work,” says Brad Keller, director of workplace strategy at Humana. “We look at it as a verb instead of a noun. Work is something you do, not necessarily a place that you go to.”

Organizations that don’t develop their talent are likely to see employees and executives jump ship to competitors that do. In our previous research, we found that employees want to work for digitally maturing companies—and that these companies were taking advantage of that desire to attract the best talent. Schumacher Clinical Partners, a national physician staffing company, is a case in point. “Doctors care about technology when deciding where to work,” says Chris Cotteleer, chief information officer. “Physicians come here because they’re attracted to the platforms and the technologies we offer. Doctors don’t like spending 30 minutes with a patient only to then spend an hour working with an electronic medical record. We provide technologies that streamline their interaction with the computer so physicians can focus on serving patients.”

In past years, we found that employees are more likely to leave if they do not have the opportunities to develop digital skills. The average shelf life for an employee skill is decreasing, which makes it critical for companies to constantly refresh development opportunities.7

This year’s results further underscore the importance of providing growth and development opportunities. Vice president-level executives who don’t feel they have access to sufficient digital development opportunities are 15 times more likely to say they are planning to leave in one year or less than are executives who have those chances. Needless to say, companies can’t afford to lose their leadership ranks at the same time that digital environments are becoming increasingly complex. (See figure 10.)

Businesses also need to be more creative in their recruitment efforts. Tambe cites Google as an example. The company has identified certain internet search terms as being indicative of the backgrounds or interests of the technical candidates it seeks. When someone enters that set of terms, they may be offered an invitation to take a short test to assess whether the candidate should be offered a more formal interview.

Yet, novel approaches are also available for companies that aren’t global search giants. For example, one organization is using questionnaires, analytics, and online interviews to be more efficient in identifying candidates and improving the recruitment experience. A director of talent acquisition we interviewed noted that technology is not only helpful in candidate assessment but can also be used to assist candidates in finding job openings.

Many organizations also emphasize recruiting from within. “We found people within the company that were in different parts of the business,” says CarMax’s Mohammad. “Some of them became product managers. We assessed the talent caliber and skill set to make sure we have the right folks in the right roles.”

Successfully assimilating new hires into the business and organizational culture can also be central to success. “There will always be this natural tension between insiders and outsiders,” says Wissam Magazachi, vice president, digital platforms at American Express. “Whenever you bring in the outsiders, it’s harder for them to get meshed into the culture. There are many people who come into the company and end up frustrated with existing culture and silos and leave. And then some people thrive in the culture and actually drive change. We have seen a bit of both. You need a bit of both.”

Do you have the will for digital transformation?

Walmart wasn’t born a digital company. It is forging its path toward digital maturity in a disciplined and systematic way. “We are constantly looking for ideas that can make a process better and faster,” says Baker. “We have purposeful conversations—whether it’s with finance, HR, or in the stores—to find and do what will help us all reach our larger aspiration and ambition of becoming a digital enterprise.”

It starts with adopting a product mindset, or as Baker puts it, “realizing that with the people function, everything we do is built with the end user and a desired outcome in mind.” Walmart’s iterative process aims to create a people-led, tech-empowered workforce, from the halls of the home office to the aisles of its stores.

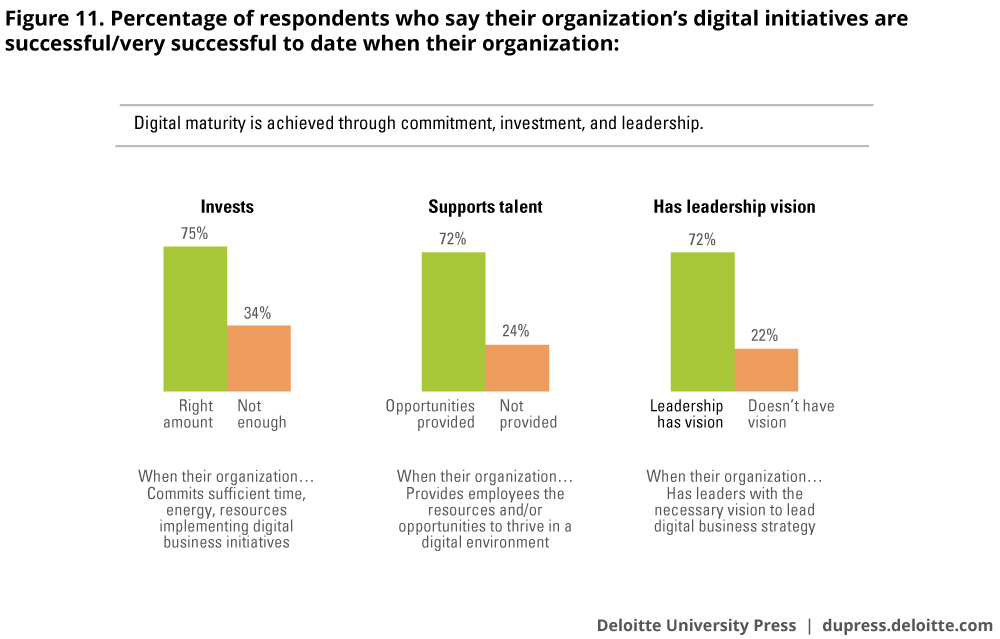

As Walmart’s approach demonstrates, digital maturity doesn’t develop accidentally, nor is it the result of a quick fix. Rather, digital maturity is achieved through commitment, investment, and leadership. Digitally maturing companies set realistic priorities, put their proverbial money where their mouth is, and commit to the hard work of making digital maturity happen.

Digital initiatives are two to three times as likely to be successful if there is sufficient commitment behind them. (See figure 11.) For example, 75% of respondents whose organizations commit sufficient time, energy, and resources to digital endeavors say these efforts are successful. Only about one-third of those who don’t make that commitment report the same results. More than 70% of organizations that provide their employees with the opportunity to thrive and whose leaders have sufficient vision to lead digital efforts say their initiatives are successful. On the part of organizations that don’t, fewer than 25% can make the same claim.

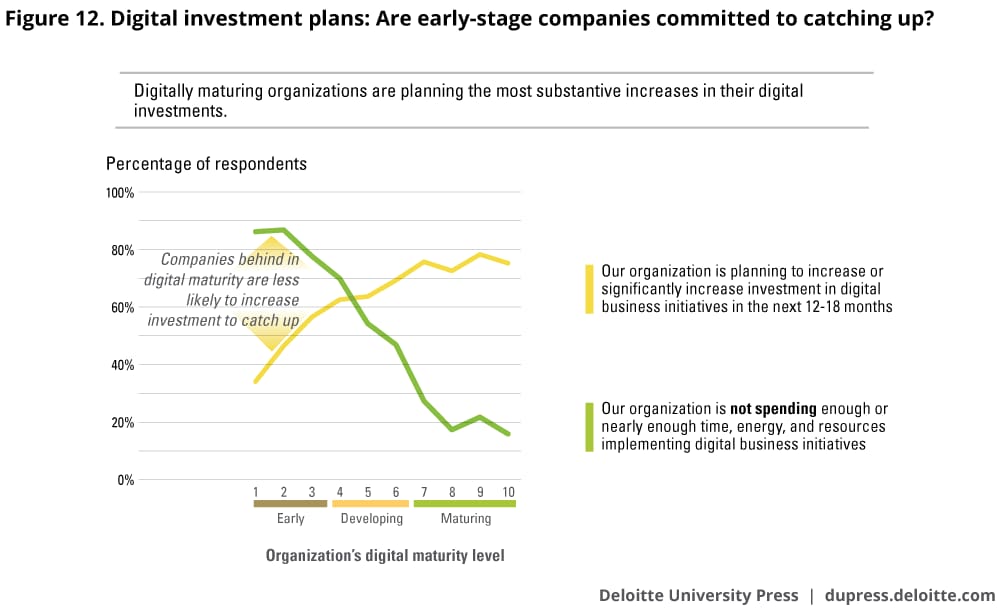

Digitally maturing businesses are also more likely to double down on their success to drive ever-greater results. (See figure 12.) Already experiencing the greatest progress with digital endeavors, these organizations are planning the most substantive increases in their digital investments: Approximately 75% of digitally maturing entities plan to increase the money and resources they put into digital business initiatives during the next 12 to 18 months. On the part of early-stage companies, the numbers drop to 49%. The gap between the digitally prepared and the rest of the pack threatens to become dangerously wide, leaving many companies decidedly unprepared to compete in rapidly changing digital environments.

Final words to the wise

The time to begin maturing is now. If an organization waits until it sees positive market proof that traditional business models are faltering, it may be too late. Becoming a mature digital business isn’t a quick process, and it requires business leaders to continuously rethink their entire business step by step from the ground up. To build a path toward digital maturity, organizations should consider embracing the following principles:

Commit to and make digital a core part of your organization: Having too many competing priorities is often the biggest barrier to achieving digital maturity. To surmount that challenge, a company’s leaders must stress that digital maturity is of paramount importance and tie digital business to the company’s core business strategy. Start with understanding your organization’s cultural traits that need to be changed—to help prioritize efforts to transform the business, customer experiences, and the bottom line. And the effort needs to include more than talk. The required change may be significant. Executives likely need to reconfigure aspects of their leadership team, organizations, workforces, and cultures to drive digital success.

Determine the funding model and generate momentum from experiments to drive scale: To ensure that organizations have the skills and resources needed to scale initiatives, leaders need to determine in advance where funding will come from. Options can range from capital funds to savings from operational improvements. To scale knowledge and build momentum, companies should develop short (8- to 10-week), intense digital initiatives or experiments. When successful, these sprints can build on each other and drive larger enterprise efforts—the heart of moving toward digital maturity.

Cultivate a culture and an organizational structure that enables digital maturity: Leaders can’t just command that the organization become more digital. They need to build a supportive culture that embraces collaboration, risk taking, and experimentation. Select the right leader(s) to drive change and have them start by focusing on the two to three areas where increased digital maturity can have the biggest and most visible impact. Our research reveals that a flexible mindset combined with a networked and team-based organizational structure supports an organization’s ability to react to digital trends and to become more digitally mature.

Strive to make the organization a talent magnet: Even the most digitally mature organizations don’t have all the needed talent. To compete, make your organization a talent magnet that recruits, retains, and develops staff with digital skills. While it’s possible to hire contractors and to recruit digital leaders to advance your efforts, our research shows that it’s imperative to develop your internal workforce. Companies often have pockets of people who want the organization to become more digital, and leadership needs to identify them and give them opportunities to develop and grow. These digital advocates are more likely to put in the required effort, and are less likely to resist changes. Put these advocates to work on the experiments and initiatives called out above and let them build and advance their skills as they make contributions to the shift in becoming a digital business.

Achieving digital maturity is an ongoing process; technology shifts and advancements, new business models, and changing market demands will continue to push companies to evolve and grow. It’s a process that takes time but can increase the likelihood that an organization will survive and thrive. Leaders in digitally maturing organizations understand that they have to take a long view, since the end points of digital change are continually being updated. Businesses have to craft strategies that account for what is on the horizon and make the objectives real through technology and business innovations.

“Through rapid iteration, we as a company are learning what is working and what’s not,” says Mohammad at CarMax. “We are going through a constant evolution.”

About the research

To understand the challenges and opportunities associated with the use of digital technology, MIT Sloan Management Review, in collaboration with Deloitte, conducted its sixth annual survey of more than 3,500 business executives, managers, and analysts from organizations around the world.

The survey, conducted in the fall of 2016, captured insights from individuals in 117 countries and 29 industries, from organizations of various sizes. More than two-thirds of the respondents were from outside of the United States. The sample was drawn from a number of sources, including MIT Sloan Management Review readers, Deloitte Dbriefs webcast subscribers, and other interested parties. In addition to our survey results, we interviewed business executives from a number of industries and academia to understand the practical issues facing organizations today. Their insights contributed to a richer understanding of the data.

Digital maturity was measured in this year’s study similar to the way it was measured in prior years. We asked respondents to “imagine an ideal organization transformed by digital technologies and capabilities that improve processes, engage talent across the organization, and drive new value-generating business models.” We then asked respondents to rate their company against that ideal on a scale of 1 to 10. Three maturity groups were observed: “early” (1-3), “developing” (4-6), and “maturing” (7-10).

Appendix

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.