Influencing stakeholders: Persuade, trade, or compel has been saved

Influencing stakeholders: Persuade, trade, or compel Executive Transitions series

09 August 2017

New executives need to identify and map their strategy for influencing stakeholders in order to bring about change. Options range from friendly persuasion to the last resort—a power play.

Executives are usually hired to drive business improvement and not just maintain the status quo. But change can be uncomfortable for existing stakeholders, and incoming executives will likely have to build the capacity to influence other stakeholders to drive change and improve performance. This essay in our Executive Transitions series focuses on how incoming executives can build the capacity to influence and effectively exercise influence to deliver on their initiatives.

Begin by mapping influence needs

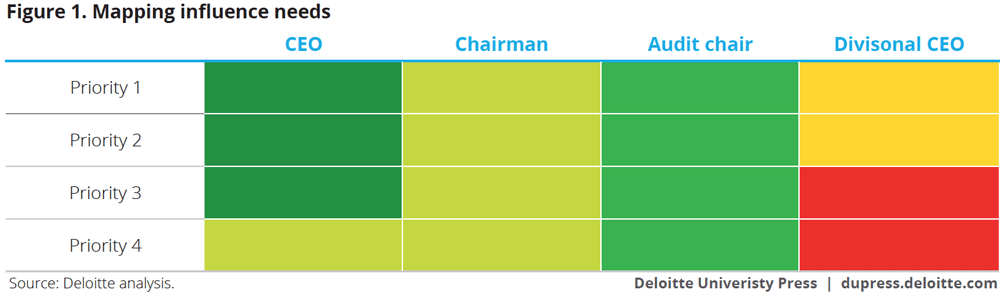

The starting point to developing an influence strategy is mapping out where you will need to spend time and effort convincing others to support your initiatives. A useful way to do this is to determine who among your critical stakeholders is likely to be a supporter, a neutral party, or blockers of your priority initiatives. One way of mapping this is to create a table like the one below where you list your top five priority initiatives by row and each critical stakeholder (beginning with the most influential individual) by column. Next fill out the resulting grid with a color indicating stakeholder support for a priority if they are relevant to the priority. For example, you may use green if they are supportive, yellow if they are neutral, and red if they are likely to block.

There are many ways to interpret the above table. The more stakeholders there are relevant to a priority the more time you will likely spend informing and communicating to them about the initiative. The more yellow and red spots in a row, the more effort it will take to persuade and influence stakeholders to support the initiative and successfully deliver it. The more red and yellow spots in a column, the greater the effort and focus needed to convince the particular stakeholder to support and not stand in the way of your collective initiatives. Understanding the influence map can help you prioritize attention to the stakeholders and initiatives that drive the design of your influence strategy.

Frame your influence strategy

As in the case of talent issues, incoming executives should invest in stakeholder relationships early. They can perhaps begin with a listening tour about what is working and what is not working with respect to their area of responsibility. Such ongoing investments in relationship building can generate the return of influence at a later time when it is needed.

There are many models of influence such as Cialdini’s six principles of influence: consistency, reciprocity, social proof, authority, liking and scarcity.1 In the labs, though, I generally observe three different types of influence responses to different types of resistance that executives confront:

- Gentle persuasion for mild or unintentional resistance

- Trade to align interests and commitments

- Power play to overcome significant resistance

Gentle persuasion: Often, stakeholders may not act with the intention to block your initiative. They may simply be busy attending to their own priorities or they may not have a clear idea of the urgency of your project and its impact on the overall business, though their delay in attending to your needs may appear like blocks. Where there are no conflicts in intention, it is probably best to consider direct communication with the stakeholder, using likeability and charm or asking for their help as a way of enlisting their support. People are often more willing to support those whom they like; so the more likeable or charming you are, the more likely the stakeholder is to support you. At other times, asking for help may also drive supportive action. Some stakeholders derive considerable satisfaction from demonstrating expertise or from helping others. Thus, a useful starting point for resolving a blockage and influencing a stakeholder may simply be direct, thoughtful, and simple communication clarifying a need and soliciting help.

Trade—Influence without authority: Communication and likeable appeals for help may not be sufficient to garner stakeholder support. And unlike a CEO, an incoming CxO may not have the operational authority and power to drive support. The next step to consider may be a trade using different currencies of influence. A trading strategy builds on the premise of reciprocity. In their book Influence Without Authority,2 Cohen and Bradford provide a useful typology of different currencies for influence that an executive can seek to accumulate and use to influence. These include among others:

- Task-related currencies such as budgets, people resources, information, and responsiveness

- Position-related currencies such as recognition and influence with other connections

- Inspiration-related currencies like vision, excellence, and ethical correctness

- Relationship-related currencies such as personal support and acceptance

- Personal-related currencies such as gratitude, autonomy, and discretion

In my work with CFOs, some currencies at their disposal that stand out are the ability to support budgets for key stakeholders, provision of people for analytic support, and improved access to information to support decision making. Beyond such task-related currencies, they can also provide recognition for financial and operational achievements or connectivity to select board members as currencies of influence. Many of the non-task-related currencies such as recognition and a reputation for excellence can take time to develop; so it’s important for incoming executives to foster relationships and develop and bank these currencies for future use.

A trading strategy can begin with a simple question to the stakeholder, “How can I help you?” Then consider which currencies are available to you to help align stakeholder commitments, actions, and interests.

Power play: Occasionally a change initiative will involve power play. Power is the ability to make decisions, allocate resources, and compel actions to carry out the decisions. In a power play, the choice is made to compel a stakeholder to take a course of action that they would not otherwise choose. Sometimes the power play diminishes the power of the other stakeholder or redraws organization reporting lines.

Consider the following situation: An incoming CFO to a high-growth private company finds out that power primarily resides with the founder corporate CEO in the center, and secondarily with divisional CEOs. Furthermore, divisional CFOs are recruited by and report to the divisional CEOs, who also control their compensation. This structure leads to rapid and sometimes undisciplined growth in the divisions, funded by debt raised at the corporate level. The incoming corporate CFO is tasked with preparing the company for an IPO and rationalizing investments and the go-forward capital structure. One of the divisional CEOs is resistant to change and is uncooperative, although the division expenditures and needs for cash have a significant financial and work impact on the incoming CFO and corporate finance. The divisional CEO and CFO do not provide timely budgets, forecasts, or requests for capital, and often go directly to the corporate CEO to authorize investments and commit resources without a thorough analysis from the center. The corporate CEO has worked with the divisional CEO for a considerable period and is favorable to approving the requests.

In order to change this uncooperative dynamic, the CFO can first try gentle persuasion of the divisional CEO. Next, they could do the same with the corporate CEO to provide the group CFO authority over all resource allocation. If that is not feasible they can try a trade with the divisional CFO. Assuming none of these strategies works, the next step to consider is to devise a power play that shifts behaviors to compliance. In the power play, the CFO can seek the authority of others and social pressure to compel more timely behaviors from the division CEOs and CFOs. Perhaps in visits with the audit chair to discuss IPO preparations, the corporate CFO works to leverage the positional authority of the audit chair by requesting more detailed scrutiny across specific divisions by the head of internal audit on behalf of the audit committee. If the audit findings are problematic, this may provide the basis for the CFO to gain the audit chair’s support to redraw reporting lines from the divisional CFOs to the corporate CFO to improve controls. It may also be the basis to replace a divisional CFO who has not established a good control environment or who has not been cooperative with the new corporate CFO.

In addition to leveraging positional authority, a complementary strategy is to leverage social proof or peer pressure. Here the CFO, along with a few of the division CEOs and CFOs, can implement a forecast and performance dashboard that clearly shows critical performance trends, future forecasts in the divisions, and how he or she can support adjustments to performance expectations and assist with corrective actions toward key targets. As some divisions provide social proof on how sharing of information leads to better outcomes, the divisions that do not participate in or provide timely and accurate information to the dashboard are likely to come under increasing peer pressure to do so. Thus, by leveraging the positional power and authority of a key leader and by establishing new norms via social proof among peers on the efficacy of timely information disclosure, the CFO can change the existing power dynamic to accomplish their mission to create a stronger control environment and more disciplined investment and execution of investment initiatives.

Power play, however, can be a costly strategy in terms of effort to communicate and build coalitions to exert pressure. Sometimes, power plays backfire in an organizational setting and the individual engaging in the power play may become an outcast from the leadership group. So power play is generally a last resort, once other approaches to influence have been tried and have failed.

The takeaway

Incoming executives are usually hired to improve performance and drive change. Delivering this change may require the consent and support of other key executives. Exercising influence to build support for change may range from conversations that leverage likeability to trading influence currencies to align stakeholder commitments and actions to your initiatives. In some difficult cases, incoming executives may have to exercise power—building on their own positional authority or the authority of other more powerful stakeholders, social pressure, and scarce resources to compel another party to more cooperative actions. Thus, understanding influence needs early and investing in relationships to build social capital can be essential for incoming executives to accumulate enough currencies to trade or establish coalitions among peers to support their initiatives.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.