Navigating the C-suite: Managing stakeholder relationships has been saved

Navigating the C-suite: Managing stakeholder relationships

08 March 2017

Among the three key resources that transitioning executives need to manage effectively—time, talent, and relationships—the last may be the most important. Addressing four critical areas of stakeholder relationship management can help avoid pitfalls and forge stronger ties with the C-suite.

Learn More

View the Executive Transitions collection

Our research (see Taking the reins: Managing CFO transitions) and our work on over a thousand transition labs to date have validated time, talent, and relationships as the three key resources that all incoming executives have to manage effectively to succeed. Among these resources, creating and establishing effective stakeholder relationships can sometimes be the most vexing and challenging task for the new executive.

Indeed, the unhappiest executives I encounter in a transition lab often have a difficult relationship challenge they must navigate in the C-suite. Difficult relationships can drain mental energy, distracting the CxO from critical tasks, and even undermine the effectiveness of their teams. Indeed, not managing executive relationships effectively can, in the worst cases, lead to isolation in the executive suite and the CEO considering replacing the new executive on the team if he or she is unable to get peer support. We also find many executives fail to invest early and adequately in relationships as they are inundated by the various tasks expected of their role. And indeed there can be many relationships to attend to; for example, CFOs have to quickly establish effective relationships with the CEO, the audit chair, the board, peer executives, and staff members as they advance their agendas. Not making adequate time to do this in the first six months often comes back to haunt them later when they need support from stakeholders for key initiatives.

From our research and work on transition labs, we have put together a few guiding principles that can help CxOs connect with and engage critical stakeholders. And explicitly addressing four areas in a transition can go a long way in establishing relationships and avoiding pitfalls. These guiding principles include:

- Determining which stakeholders are critical early and scheduling time with them

- Knowing what critical stakeholders want—and, more importantly, knowing what they do not want

- Adapting communication styles to the context and the personalities of individual stakeholders you want to relate to

- Connecting where key conversations occur

Determining the critical stakeholder set

The first step to effectively establishing and managing relationships is determining the critical stakeholder set. The obvious stakeholders in the C-suite are the CEO and peer executives. In addition, there may be other critical relationships outside the C-suite. For example, the CFO would want to have a strong relationship with the audit chair and other select board members. There may also be some other employees in the company in the C-suite and, often, outside the C-suite who are well-respected by and influential with the CEO or other key stakeholders.

As a first step, it is important to determine which individuals can significantly influence your success in your new role, either directly or indirectly. These include the obvious peers and those who are not peers but who are influential. Next, it is important to schedule time with these critical stakeholders—ideally for face-to-face meetings, or if that is impossible in the near term due to location differences, connect with them by telephone. Ideally, work with your executive assistant and have him or her try to schedule a get-together with each of your key stakeholders within the first 45 days to two months. Large companies can have many stakeholders, from presidents of four or five divisions to five to ten other leaders in the C-suite or the extended leadership team. Preparing for and attending meetings with these stakeholders will likely take at least half a week to a full week of work time in the first two months of your new role.

Listening tours can be valuable in getting a read on your organization and potentially your brand and the brand of the organization you inherited with stakeholders. Preparations for your listening tour with your stakeholders can also involve talking to your own team members who face off with a particular division or area. Even if your primary focus is to listen, it is important to get your team’s perspective on issues in any specific area and be able to get inputs from the stakeholders on the issues. For example, one CFO in retailing visited all the senior leaders of the company. He acknowledged that both the company and the finance function had made progress in recent years, but he wanted to know “how to go faster going forward, what issues clients wanted to fix, and how finance could help.” He followed up on each meeting with a return visit to play back what he had learned, giving them a perspective through the lens of the finance team on how finance was working and how it could contribute better. This proved invaluable in considering major partnering issues. “Even though I had been here a long time, it wasn’t until I started to talk to people that I really learned what they actually thought. Make sure you begin to unpack the old issues, and spend time with your internal customers talking about what’s working and what’s not working. Like all things, it’s always a two-way street.”

Prioritizing critical stakeholders and following through with a listening tour helps identify stakeholders’ needs and issues that you will likely have to address. Prioritizing ensures that you meet key influencers quickly in the process. To accelerate relationships, it is sometimes helpful to recruit the help of well-respected members or influencers in the company as an introductory reference. But while referential trust is helpful in building a relationship, you will ultimately need to translate this to reputational trust earned through actions that sustain and grow specific relationships.

Know what stakeholders want and what they do not want

Our research and work on transitions finds new CxOs often undertake listening tours to understand what their key stakeholders “want.” These conversations are seen as vital to establishing relationships and to addressing any legacy issues your newly inherited organization may have with these stakeholders. But despite these conversations, CxOs often run into roadblocks to their initiatives due to a lack of information.

To better know what key stakeholders want, CxOs should:

- Consider “walking in the stakeholder’s shoes” and hypothesizing what key stakeholders would want or what you would want of a new executive hired on your team. Some of the most common “wants” we encounter from CEOs of a new C-suite member

in our executive transition labs include:

- Understanding how the business works. In particular, for executives coming from outside the organization, the C-suite wants to see the new CxO really reaching out to peer business operators and learning the nuances of the various businesses and how they make money.

- Establishing good working relationships with peers. CEOs want to see the new CxO work to establish trusted relations with his or her peers.

- Bring focused solutions not just problems. Often CEOs note they want the new CxO to separate the forest from the trees and, most importantly, think through solution alternatives when raising a problem.

- Recruiting and managing a strong team. This helps improve the capabilities of the companies and creates stability.

- Good stewardship of their function. Make sure the basics of the responsibilities are well taken care of and commitments met.

- Partnership on strategy and change. The ability to translate the change agenda of the CEO into actionable steps and help inform strategy.

- Confidence. The ability to confidently challenge and bring different perspectives to discussion. The CxO while challenging the CEO may want to have private discussions with the CEO on areas of differences and concern.

- Understand that what stakeholders say they “want” may not express their entire universe of “wants.” For example, a business unit leader may say he needs better information and support from finance to create budgets or make investment decisions. But his true “want” may be that the finance organization “listen” to what he has to say, or he may want finance to help support the personal initiatives he believes will advance his career. By understanding stakeholders’ true wants, you can better identify the currencies you can use as a CxO to gain support and sponsorship for your agenda.

- Know that what key stakeholders do not want is as important as, or more important than, knowing what they want. Imagine, for example, an entrepreneurial CEO who hires a COO to help build better processes. The COO dutifully designs those processes only to find the CEO reluctant to implement them. To the CEO, the processes he or she thought were needed undermine the collaborative, entrepreneurial approach to problem-solving prevalent in the organization. In the quest for efficiency, the COO misread the importance of the existing culture and values because the COO didn’t know what the CEO did not want. Thus, due diligence to find out what key stakeholders do not want is as vital as discovering what they want.

Knowing what people truly do or do not want begins with questions. But as we have noted, it is often difficult for stakeholders to clearly articulate what they do and do not want. A savvy CxO will need to construct and test his or her own hypotheses of “wants” and “don’t wants” through a series of conversations directly with stakeholders or indirectly with his or her peers.

Adapting communication styles

In our transition labs we find many CxOs get into relationship difficulties because they have a communication style that works counter to the style of their key stakeholders. There are many different typologies for personality, such as the Myers-Brigg Type classification or TetraMap. Many of the typologies derive from the work by psychologist Carl Jung and provide similar guidance on how to adapt communications to different styles.

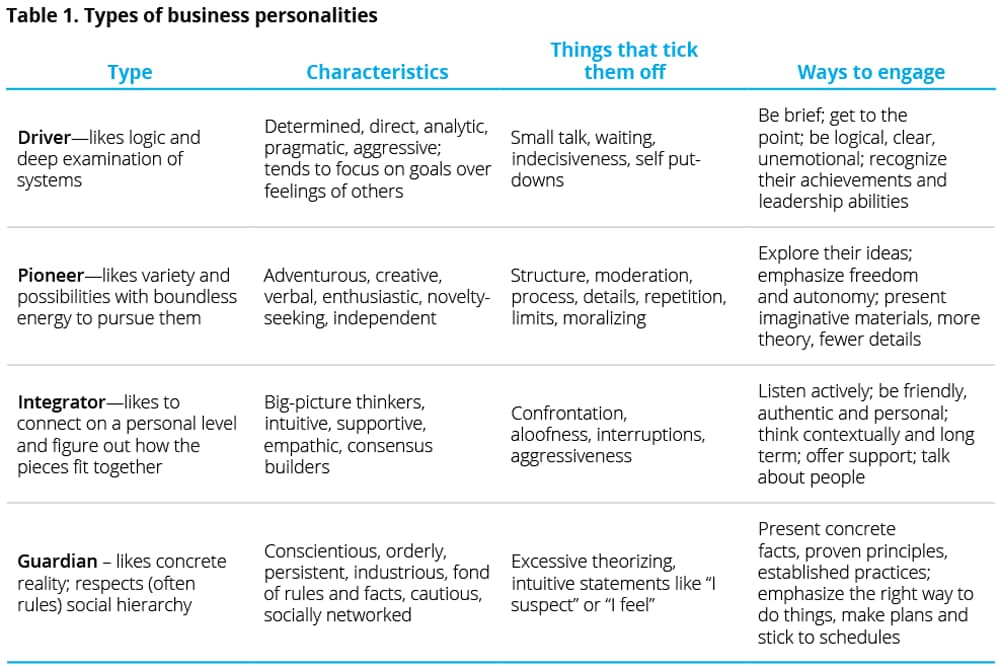

At Deloitte, we have co-developed a typology of business personalities rooted in the work of Dr. Helen Fisher, a well-known author and research professor in the Department of Anthropology at Rutgers University, which we abbreviate in table 1.1 This Business Chemistry typology focuses on effective interactions between its four key types.2 A person could be more than one type—dominant in one and secondary and tertiary in others.

Awareness of personality types can help CxOs modify how they communicate to be better heard and understood by their stakeholders. In my transition labs with CFOs, they usually hunch themselves primarily into the driver or guardian categories, their CEOs primarily into the driver and pioneer categories, the CHRO into the integrator category, and the audit chair into the guardian category.

Another communications issue I encounter with very bright functional executives is how fast they speak or solve problems in meetings. For example, many CFOs I work with are very smart, but can lose their peer audience if they arrive at conclusions and communicate them while others are still getting a handle on the problem. Speaking fast also makes it difficult for the audience to hear and process what you are trying to communicate. This is especially the case with multinational leadership teams where English is a second language for some. Thus, modulating communication style to the needs of the audience can set a more positive context for relationships going forward.

Connecting where critical conversations occur and making time

As an incoming executive it is also important to attend social and other events that bind key people in the organization together and to go where the informal conversations occur. Sometimes this may be at the bar over drinks as a group after work. It could be other social events that occur outside of normal work hours. Being absent from these meetings is noticeable, especially in the early phases of joining a new company, and is sometimes a negative observation from stakeholders in our pre-lab interviews.

For some incoming executives the social setting may be awkward or compete with other family priorities. For example, imagine you are a teetotaler and much of the work socializing occurs after hours at the pub next to your office. You may naturally be inclined to skip the pub, but attending to converse while skipping the drink will likely help you read the issues in the organization better, connect more personally with stakeholders, and help establish an ongoing relationship of value later. So identify and engage stakeholders where they converse.

Most stakeholders also want to be helpful to an incoming executive. One observation we have from our transition labs is that some incoming executives do not take advantage of this, especially if the stakeholder is a highly accomplished board member or is perceived to be a very busy executive. Scheduling time to update them at a regular cadence or finding time to meet with them if you are traveling to their city on another matter helps bind the social ties to be more effective.

The takeaway: Incoming executives have to establish effective stakeholder relationships and this can demand considerable time in a transition. Not investing in these relationships early can undermine future success. Determining, prioritizing, and scheduling a listening tour with key stakeholders early can help start the relationship. Discovering what they want and do not want, and awareness of their personality type can shape more effective communications with these stakeholders. Finally, making time and connecting with stakeholders in venues that may not be work venues where critical conversations occur is also important to effectively connect and engage with stakeholders and build effective relationships.