Architecting an operating model A platform for accelerating digital transformation

11 minute read

05 August 2019

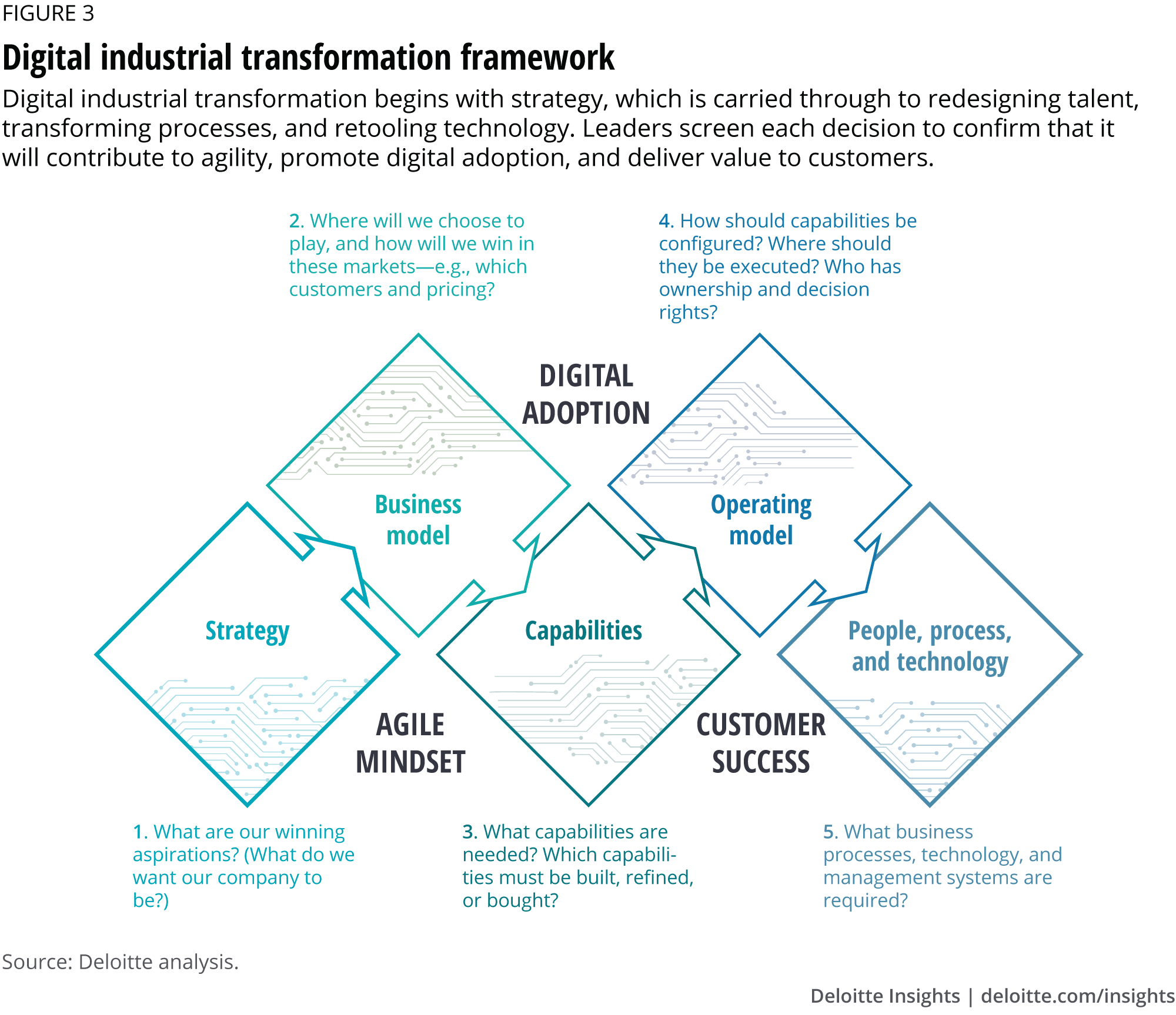

Many transformation efforts begin with reinventing the operating model. How to keep such a big project on track? This article, fourth in a series, explores how successful transformations align models with clear strategies.

Across a broad spectrum of sectors, artificial intelligence (AI), digital, the Internet of Things (IoT), process automation, and other technologies are shifting value from manufacturers and distributors to companies that operate end-to-end platforms and provide outcomes as-a-service. For many enterprises, that means constant change and disruption—and a growing threat of market obsolescence.

Learn more

Explore the Digital industrial transformation collection

Explore the Industry 4.0 collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content

Leaders, revising their five-year plans every quarter, are seeking ways to constantly reinvent their companies to stay ahead of the pack, with competitors of varying capabilities and scale and customers who expect more for less. And for many companies, the answer is large-scale global transformation. Indeed, 80 percent of CEOs in one study claim to have transformations in place to make their businesses more digital; 87 percent expect to see a change in their operating models within three years.1

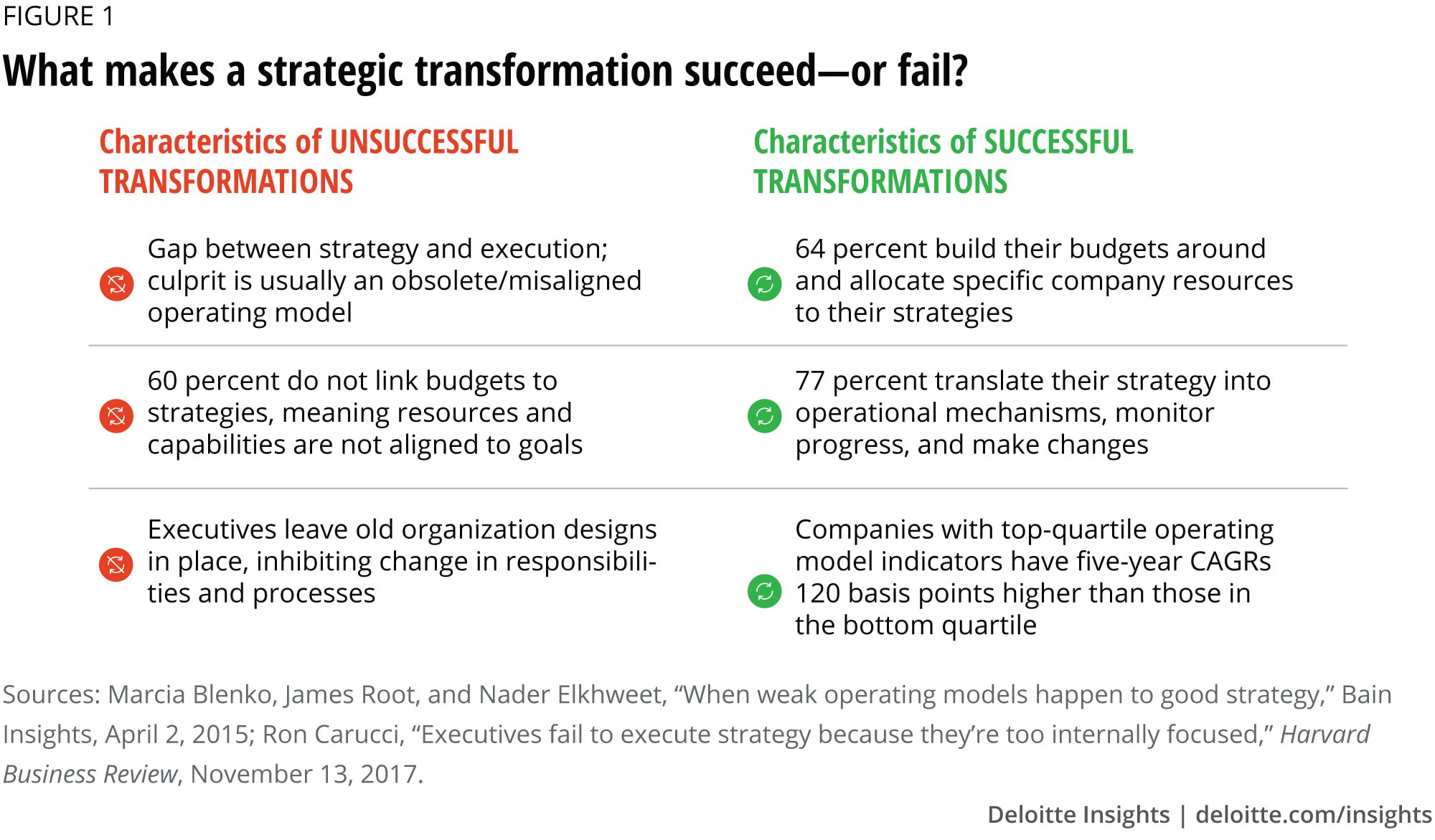

But leaders see establishing those operating models as their top challenge in achieving digital transformation.2 So how might they move forward? Reviewing transformations across industries reveals a common theme: Successful transformations realign the organization to a singular vision; failed endeavors typically do not. In short, an organization has a far better chance at succeeding when an operating model—or how an organization creates value—is aligned to the strategy. And this means that, for transformations to succeed, leadership teams should examine and possibly revise their organizations’ operating models. (See figure 1.)

Balancing growth and risk

Given the pace of change—and the volatility in the impact of potential disruptors—executives may struggle to determine where to place bets, how much to invest, and when to do it. Wait too long and they risk seeing market value quickly erode; invest inefficiently or ineffectively and they could face a cash crunch or investor backlash. Management teams must increasingly balance growth and risk. We consistently see executives try to solve for six questions—each of which can fundamentally pull the organization in a different direction, all of which are critical in the effort to “win” in the digital economy.

Executives often ask themselves, How do we:

- Grow amid increasing market and customer expectations

- Respond faster to market and competitive disruptions

- Simplify organizational processes, both internal and external

- Maximize returns on limited financial and human capital

- Incubate and test new products and technologies

- Pivot to competitive business models

The good news for companies born before the digital era is that they often quickly understand the value in transforming to agile, adaptive, and responsive enterprises because they already have the other intangibles in place: strong brands, an entrenched customer base, established sales methods, and partners—suppliers, distributors, and technology.

Successfully driving these changes, though, depends on executives addressing a range of organizational barriers and risks—particularly functional silos, incomplete enterprise data, and a product-out (versus a market-in) philosophy of value creation. In our experience, a well-designed and purposefully executed enterprise operating model can help companies balance growth with risk and overcome organizational barriers.

At one global consumer technology company, executives set out to unify the organizational vision across AI and machine learning (ML) technology. The company made a strategic decision to bolster its capabilities through acquisition of a startup and hiring new talent, combining teams dealing with ML and voice-assistant technology. The changes resulted in unified leadership and aligned incentives across development functions and product lines; the company has since embedded its AI offering into new products, extended the reach of the operations performed, and launched new software centered around AI and ML.

Target operating model

Before addressing the value of an operating model, we must first acknowledge the potential for widespread confusion and disagreement: Poll any number of executives, and you’ll likely find yourself with as many definitions of operating model. But most commonly, operating model transformations are associated with cost takeouts or organizational redesigns—“box and wire diagrams.” While these can be byproducts of an operating model shift, the common associations are myopic and discount the full value.

Our definition of an operating model is simple but comprehensive: An operating model represents how value is created by an organization—and by whom within the organization.

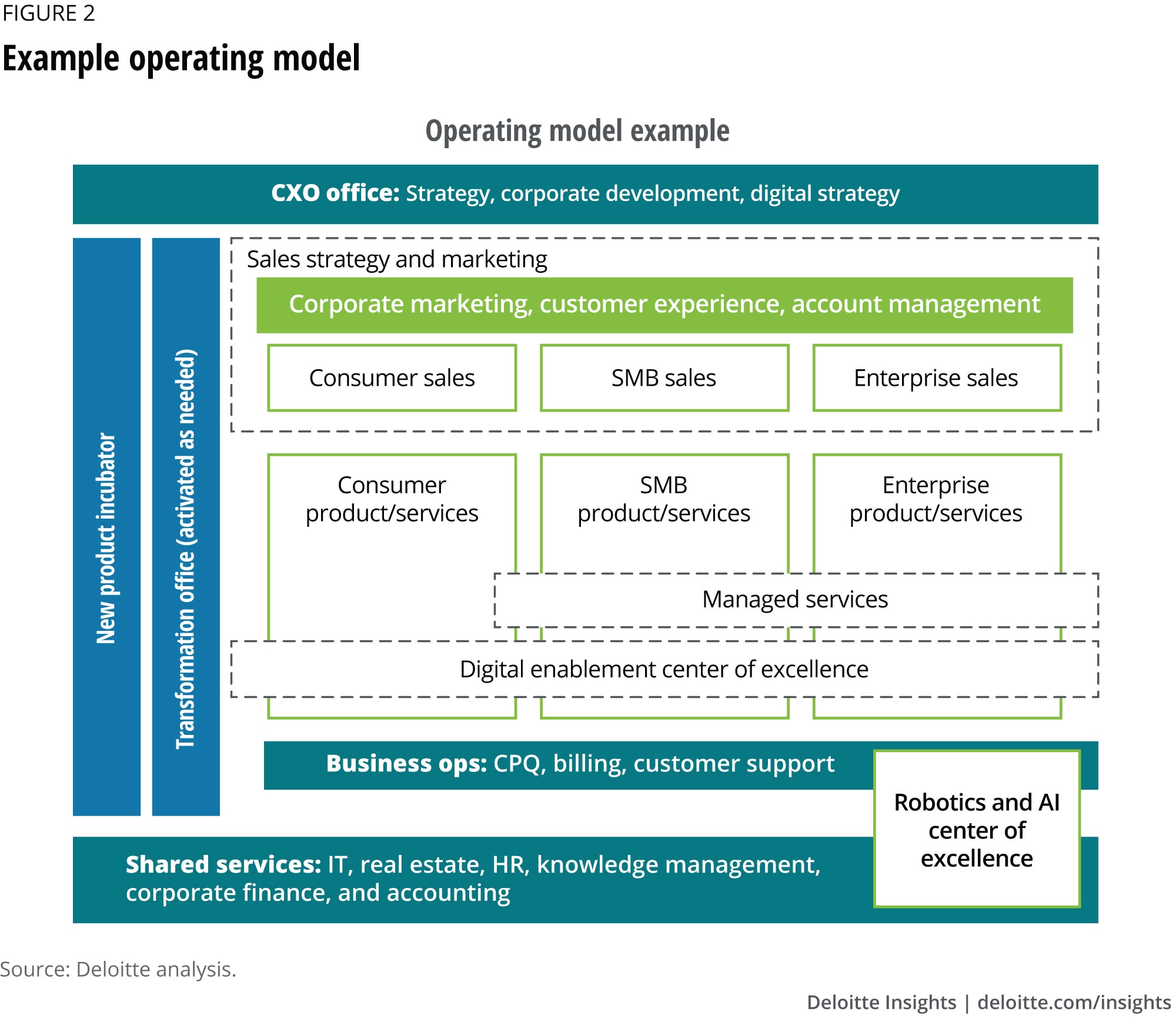

To better illustrate this, figure 2 depicts an example of an operating model; each box represents a unique set of capabilities aligned to the enterprise’s strategy, with skilled leadership teams, tailored metrics, unique investment profiles, and tight coordination across the value chain.

This illustration lays out the characteristics of this example’s operating model:

- Centralized strategic planning functions to set a unified direction for the enterprise

- Emphasis on customer experience with consolidated marketing, account management, and customer experience functions

- Independent business lines (consumer, small/medium businesses, enterprise) responsible for product, operations, etc.

- Close partnerships between product and sales teams using product-aligned sales teams, with some overlap

- Separate product and business incubator with end-to-end responsibility and direct access to C-suite

- Managed services overlay for SMB and enterprise customers

- Digital enablement center of excellence (CoE) to drive companywide adoption of tools and technologies

- Centralized business ops teams—likely offshore—to drive economies of scale

- Robotics and AI CoE to drive operational efficiencies in mid- and back-office operations

Most critically, an organization’s operating model must be inextricably linked to the corporate and business-unit strategy and varying business models. The operating model is the anchor for the enterprise and is critical to the strategy’s effectiveness and longevity. And understanding how your organization maps onto the model is key to an effective digital transformation.

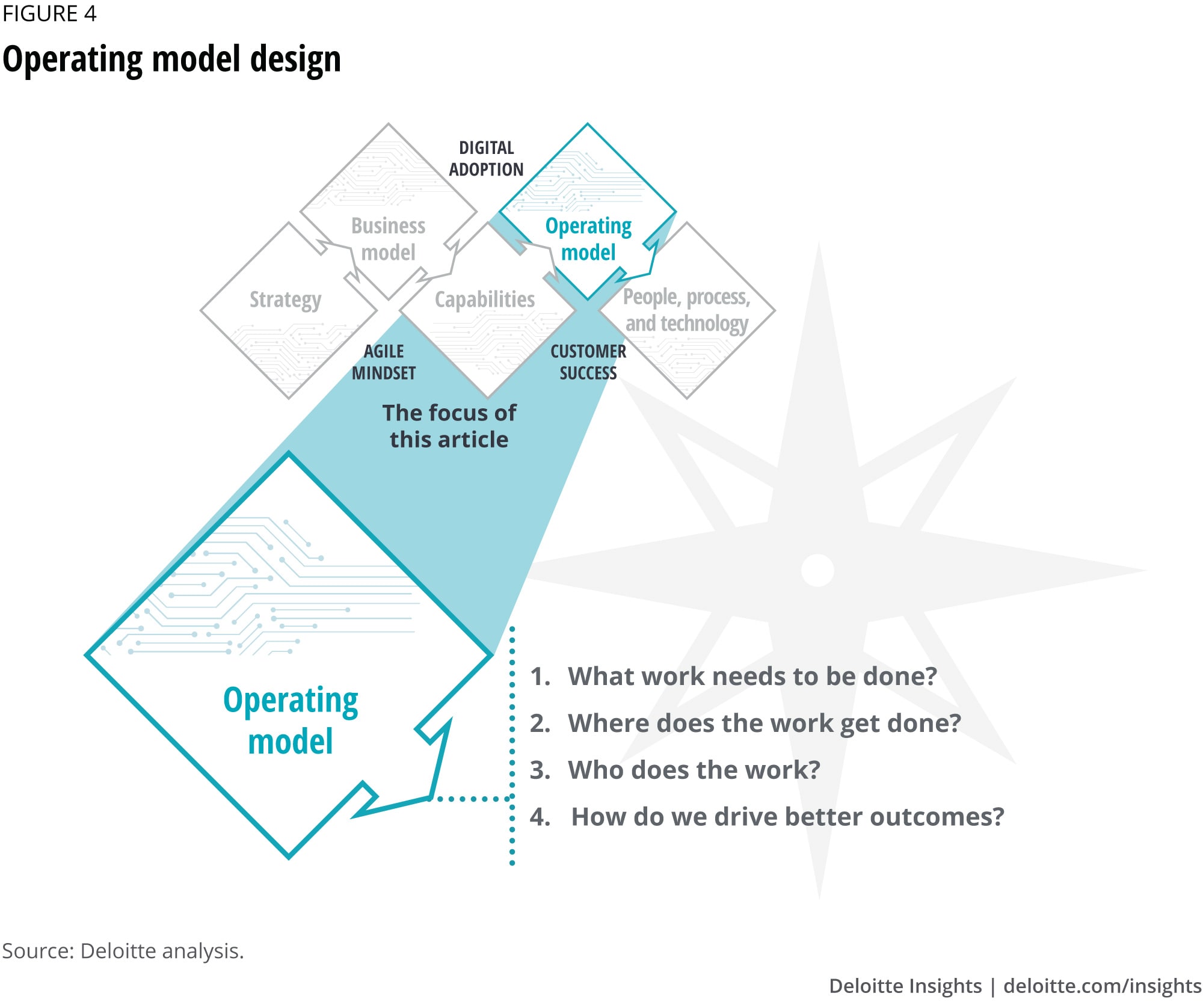

Operating model design

Leaders should develop a clear sense of their strategic ambitions—where to play and how to win—and the business models they wish to employ, including target customer segments, channels, pricing, and delivery models, since both the strategy and business model directly influence the operating model design. Organizations that try to short-cut their way to a new operating model may find the design to be ineffective and the implementation lacking employee traction—or, worse, dilutive to value.

A global entertainment company aimed to share technology across its business units to improve customer experience. In 2013, for the first time in nine years, the company effected a large reorganization: combining console and handheld divisions. The change was driven by criticism about a “lack of a unified vision” related to previous launches. Executives intended the new structure to promote sharing of technology across groups, and thus far it has worked, with the company launching its most successful console to date.

What work needs to be done?

In moving forward with a digital transformation, the first step is to identify the holistic set of capabilities required to meet the enterprise’s strategic ambitions. The capability set should include both existing capabilities and new ones (as needed) and address front-, mid-, and back-office functions across all product lines.

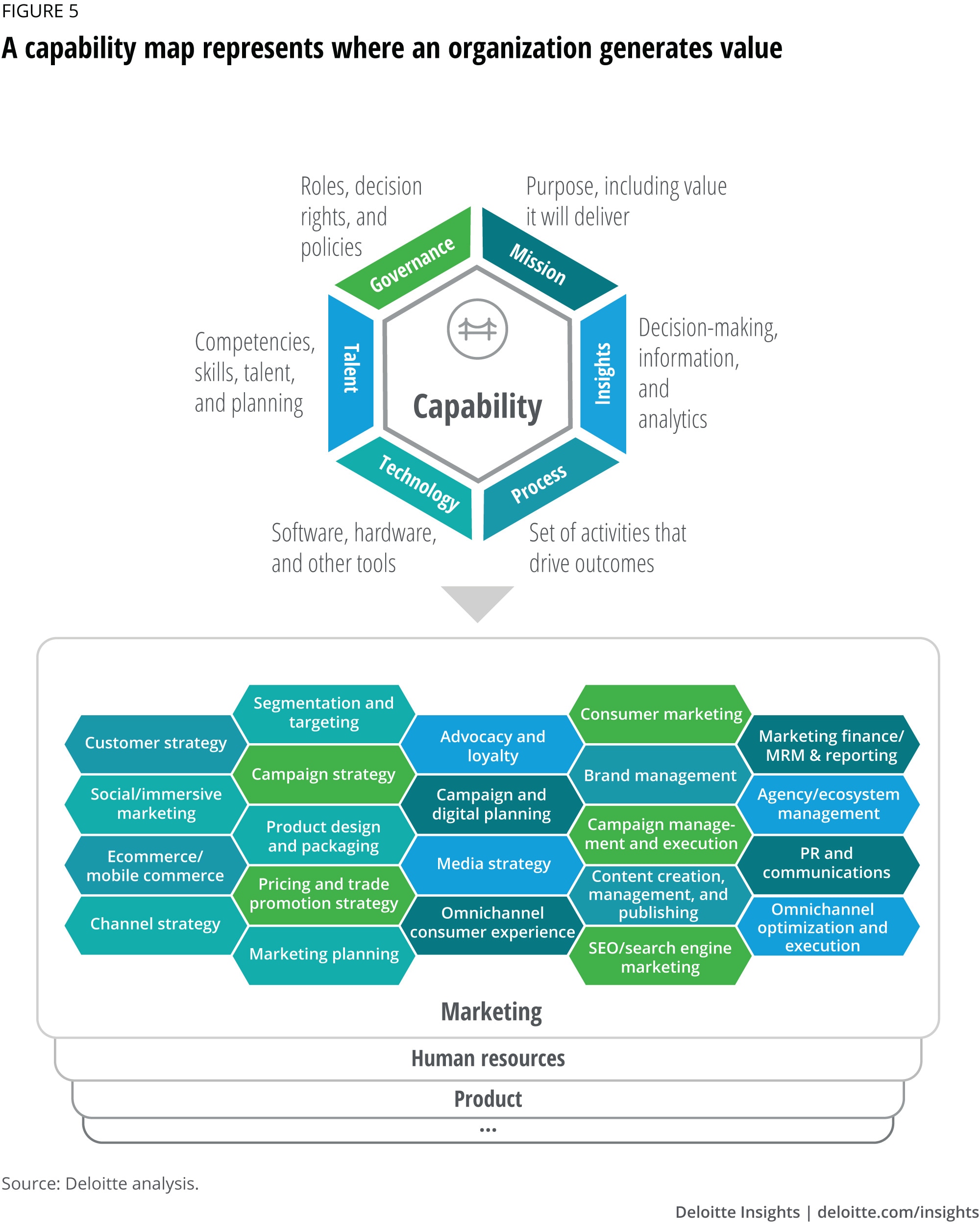

A capability represents a discrete set of objectives, processes, technologies, and talent that collectively generate value for an organization.

For example, product strategy is a capability that creates product road maps to realize customer requirements; campaign management is a capability that launches, measures, and reports on the success of marketing campaigns. When brought together, capabilities comprise a capability map, representing the collective set required to execute against the strategy and business model.

A capability map provides a foundation on which organizations can build their target operating model. Moreover, capabilities serve as building blocks for the organization—they can be used to determine skill set requirements, hire talent, set performance metrics, build teams, and identify partnership opportunities.

Where does the work get done?

Once leaders have established the capability map, the next step is sourcing capabilities. Several capabilities will likely already exist—some mature or fit-for-purpose, others recent arrivals. This step is often the most difficult to execute, as companies can be resistant to change their existing ways of working when instead they can leverage the opportunity to untether themselves from legacy processes and technologies.

Enterprises typically have four sources for capabilities: They can develop, transform, or mature them internally (use as is); they can acquire capabilities through targeted hires, or outright M&A; they can partner to access them; or they can outsource the capabilities and have them delivered as-a-service. The decision to develop, acquire, partner, or outsource is a critical one, since each lever provides organizations unique advantages. Executives should consider the following in making decisions:

- Speed. How urgently do we need this capability?

- Control. How important is it that we control the outcomes?

- Specificity. To what degree do we need to tailor this capability to our business?

- Competitive advantage. To what extent does this capability provide us an edge over competitors?

- Operational leverage. How much do we want to take on in fixed/on-balance-sheet commitments?

Each of the four sourcing options varies widely across this spectrum and has different use cases (see figure 6).

The choice is distinct for every organization. Take the case of an industrial products company: The management team may decide to own manufacturing capabilities because the company’s processes and technologies give it a competitive advantage, even though this means operating with a higher base of fixed costs and regularly investing in talent and technology upgrades. On the other hand, a technology company may choose to outsource manufacturing—the same capability—given the variety of low-cost providers available in other countries.

Among the toughest decisions leaders can make is to decommission an owned capability and opt to partner or outsource it.

While this may be painful in the short term, these decisions can accrue long-term value by freeing up cash and receiving best-in-class service. For example, one company trying to establish a digital gaming platform chose to partner with established hardware providers rather than build its own controllers. Executives chose to control and focus on their core value (customer experience) while partnering for scale (labels, platforms, devices).

Who does the work?

Simply said, this step involves allocating work to the most efficient parts of the organization.

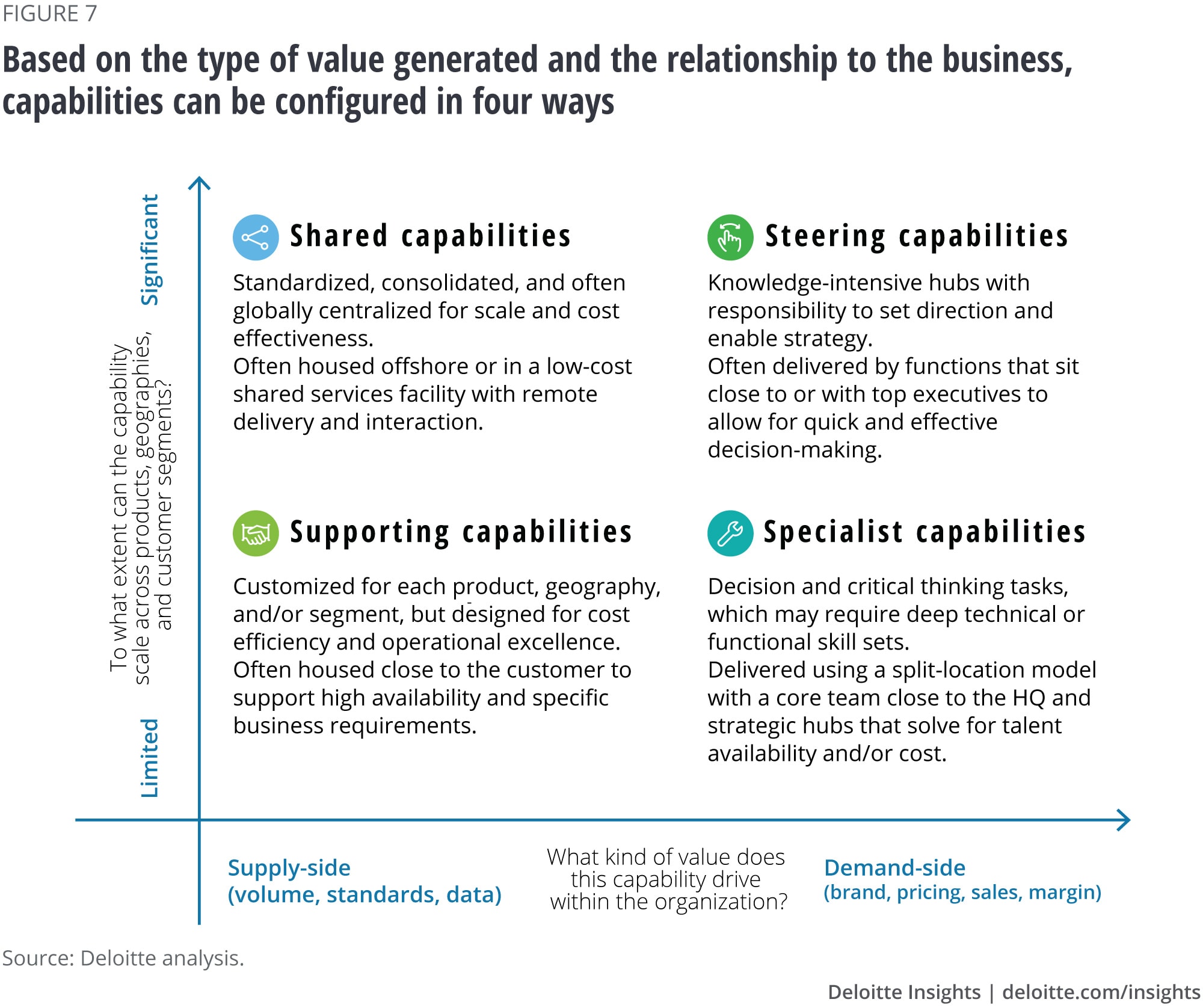

Capabilities (see figure 7) typically provide one of two types of value: demand-side or supply-side. Demand-side advantages drive increased attention toward a company’s offering, driving up pricing, revenues, and margins. Typically, these include capabilities such as sales, product engineering, recruiting, branding, and corporate strategy, where processes and skill sets are less repeatable, and where talent is a significant driver of value. Supply-side advantages allow a company to operate more effectively and get the most out of resources. These usually include areas in which value is related to scale, such as sales-quote capabilities, self-service, accounting, and manufacturing.

Similarly, the relationship to the business is twofold. Capabilities significantly tethered to the line of business often rely on some expert ability such as localization, R&D, product marketing, or technical sales. Those with limited relationship to the business—for instance, M&A, e-commerce, and supply chain management—rely on generalist skill sets and play across the enterprise.

In our experience, each capability has a different place within the operating model. For example, shared capabilities are often offshored, or even outsourced. Steering capabilities are delivered close to the headquarters (and executives) given decision-making velocity, while specialist capabilities can be structured as centers of excellence.

More importantly, companies can opt for different ways to deliver similar capabilities—and those decisions should be closely linked to the strategy. For example, a ride-hailing company with comparatively simple customer support requirements may choose to automate most functions in a shared service, offering specialized support or premium support only as a supporting capability. On the other hand, a cutting-edge electric-car maker might structure customer support as a specialist capability, with highly trained and available staffers who can solve a variety of problems, become product advisers, and potentially even upsell customers.

How can organizations drive better outcomes?

Operating models are ever-evolving, driven by feedback from employees and customers, the effectiveness of business processes, and evolving competitive landscapes. Leading organizations augment their capabilities through simple cross-functional processes, hyper-focused incentives, and best-in-class tools to drive simplicity, clarity, and speed in execution.

When assets—people, processes, and technologies—cease to deliver value, leaders should consider taking steps to upgrade or replace them. We have observed that companies whose execution embodies three evergreen principles are often successful at getting the most out of their operating models. (See figure 8.)

Building a functioning model

Given the challenges of effecting a digital transformation—particularly the intangible benefits—having in place an optimized and strategy-aligned enterprise operating model can be a tremendous help. When executed well, an enterprise operating model can improve resource utilization and efficiency, reinforce an outcome-based culture and mindset, and aid communication, collaboration, and knowledge-sharing. But the potential challenges in designing and implementing an operating model transformation are clear, from organizational resistance and misaligned visions to poor execution and missing data.

Our research points to at least six ways to potentially increase your chances of building a model that can help guide a successful digital transformation:

- Nominate and empower function and business leaders early on to drive the cultural change required across the organization

- Define clear roles and responsibilities across businesses, regions, and functional support groups

- Create complementary incentives and goals for businesses and functions to reduce conflict and optimize resource allocation

- Establish cross-functional debriefs to keep relevant parties informed, and nominate an owner to manage the process early

- Institute a governance model with clear KPIs for each leadership team—one that supports quick, independent decision-making

- Standardize resource and knowledge exchange to ensure that skill sets are cultivated and proliferated

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more from Industry 4.0

-

Industry 4.0: At the intersection of readiness and responsibility Article5 years ago

-

The Industry 4.0 paradox Collection6 years ago

-

When the Internet of Things meets the digital supply network Article5 years ago

-

Ethical technology use in the Fourth Industrial Revolution Article5 years ago