Opting in: Using IoT connectivity to drive differentiation has been saved

Opting in: Using IoT connectivity to drive differentiation The Internet of Things in insurance

03 June 2016

Connectivity is changing the way people engage with their cars, homes, and bodies—and insurers are looking to keep pace. Even at an early stage, IoT technology may reshape the way insurance companies assess, price, and limit risks, with a wide range of potential implications for the industry.

Insurers’ path to growth: Embrace the future

In 1997, Progressive Insurance pioneered the use of the Internet to purchase auto insurance online, in real time.1 In a conservative industry, Progressive’s innovative approach broke several long-established trade-offs, shaking up traditional distribution channels and empowering consumers with price transparency.

Receive IoT insights

Subscribe

Explore the

Internet of Things collection

This experiment in distribution ended up transforming the industry as a whole. Online sales quickly forced insurers to evolve their customer segmentation capabilities and, eventually, to refine pricing. These modifications propelled growth by allowing insurers to serve previously uninsurable market segments. And as segmentation became table stakes for carriers, a new cottage industry of tools, such as online rate comparison capabilities, emerged to capture customer attention. Insurers fought to maintain their competitive edge through innovation, but widespread transparency in product pricing over time created greater price competition and ultimately led to product commoditization. The tools and techniques that put the insurer in the driver’s seat slowly tipped the balance of power to the customer.

This case study of insurance innovation and its unintended consequences may be a precursor to the next generation of digital connectivity in the industry. Today, the availability of unlimited new sources of data that can be exploited in real time is radically altering how consumers and businesses interact. And the suite of technologies known as the Internet of Things (IoT) is accelerating the experimentation of Progressive and other financial services companies. With the IoT’s exponential growth, the ways in which citizens engage with their cars, homes, and bodies are getting smarter each day, and they expect the businesses they patronize to keep up with this evolution. Insurance, an industry generally recognized for its conservatism, is no exception.

The IoT is fundamentally a technology architecture stitching together existing technologies in a specific way so that new benefits can be achieved.

IoT technology may still be in its infancy, but its potential to reshape the way insurers assess, price, and limit risks is already quite promising. Nevertheless, since innovation inevitably generates unintended possibilities and consequences, insurers will need to examine strategies from all angles in the earliest planning stages.

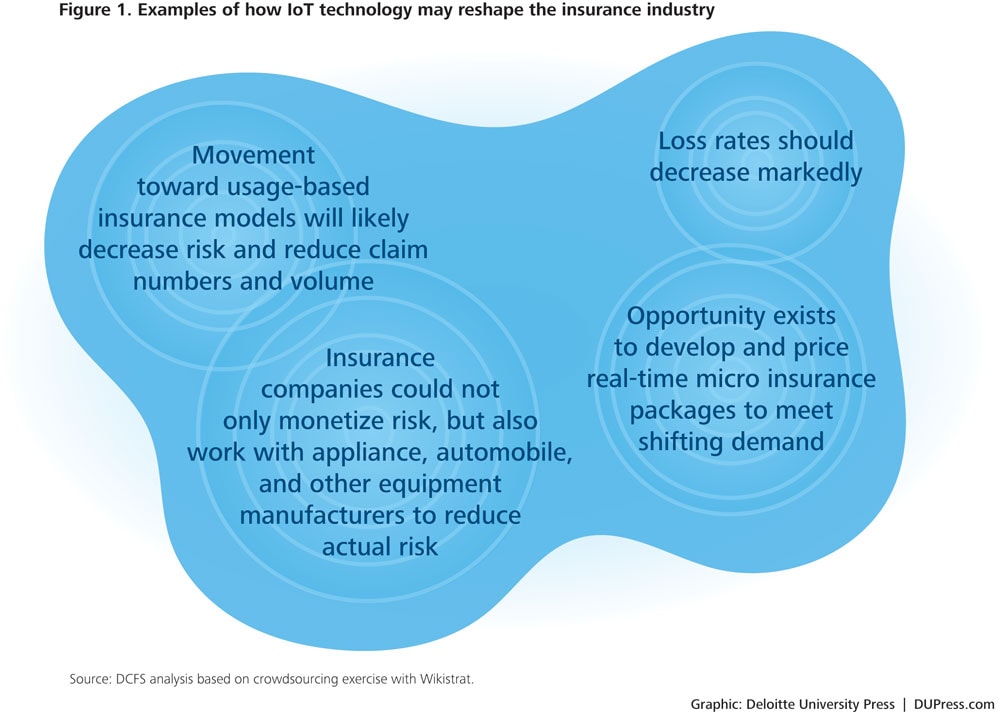

To better understand potential IoT applications in insurance, the Deloitte Center for Financial Services (DCFS), in conjunction with Wikistrat, performed a crowdsourcing simulation to explore the technology’s implications for the future of the financial services industry. Researchers probed participants (13 doctorate holders, 24 cyber and tech experts, 20 finance experts, and 6 entrepreneurs) from 20 countries and asked them to imagine how IoT technology might be applied in a financial services context. The results (figure 1) are not an exhaustive compilation of scenarios already in play or forthcoming but, rather, an illustration of several examples of how these analysts believe the IoT may reshape the industry.2

Connectivity and opportunity

Even this small sample of possible IoT applications shows how increased connectivity can generate tremendous new opportunities for insurers, beyond personalizing premium rates. Indeed, if harnessed effectively, IoT technology could potentially boost the industry’s traditionally low organic growth rates by creating new types of coverage opportunities. It offers carriers a chance to break free from the product commoditization trend that has left many personal and commercial lines to compete primarily on price rather than coverage differentiation or customer service.

For example, an insurer might use IoT technology to directly augment profitability by transforming the income statement’s loss component. IoT-based data, carefully gathered and analyzed, might help insurers evolve from a defensive posture—spreading risk among policyholders and compensating them for losses—to an offensive posture: helping policyholders prevent losses and insurers avoid claims in the first place. And by avoiding claims, insurers could not only reap the rewards of increased profitability, but also reduce premiums and aim to improve customer retention rates. Several examples, both speculative and real-life, include:

- Sensors embedded in commercial infrastructure can monitor safety breaches such as smoke, mold, or toxic fumes, allowing for adjustments to the environment to head off or at least mitigate a potentially hazardous event.

- Wearable sensors could monitor employee movements in high-risk areas and transmit data to employers in real time to warn the wearer of potential danger as well as decrease fraud related to workplace accidents.

- Smart home sensors could detect moisture in a wall from pipe leakage and alert a homeowner to the issue prior to the pipe bursting. This might save the insurer from a large claim and the homeowner from both considerable inconvenience and losing irreplaceable valuables. The same can be said for placing IoT sensors in business properties and commercial machinery, mitigating property damage and injuries to workers and customers, as well as business interruption losses.

- Socks and shoes that can alert diabetics early on to potential foot ulcers, odd joint angles, excessive pressure, and how well blood is pumping through capillaries are now entering the market, helping to avoid costly medical and disability claims as well as potentially life-altering amputations.3

Beyond minimizing losses, IoT applications could also potentially help insurers resolve the dilemma with which many have long wrestled: how to improve the customer experience, and therefore loyalty and retention, while still satisfying the unrelenting market demand for lower pricing. Until now, insurers have generally struggled to cultivate strong client relationships, both personal and commercial, given the infrequency of interactions throughout the insurance life cycle from policy sale to renewal—and the fact that most of those interactions entail unpleasant circumstances: either deductible payments or, worse, claims. This dynamic is even more pronounced in the independent agency model, in which the intermediary, not the carrier, usually dominates the relationship with the client.

The emerging technology intrinsic to the IoT that can potentially monitor and measure each insured’s behavioral and property footprint across an array of activities could turn out to be an insurer’s holy grail, as IoT applications can offer tangible benefits for value-conscious consumers while allowing carriers to remain connected to their policyholders’ everyday lives. While currently, people likely want as few associations with their insurers as possible, the IoT can potentially make insurers a desirable point of contact. The IoT’s true staying power will be manifested in the technology’s ability to create value for both the insurer and the policyholder, thereby strengthening their bond. And while the frequency of engagement shifts to the carrier, the independent agency channel will still likely remain relevant through the traditional client touchpoints.

By harnessing continuously streaming “quantified self” data, using advanced sensor connectivity devices, insurers could theoretically capture a vast variety of personal data and use it to analyze a policyholder’s movement, environment, location, health, and psychological and physical state. This could provide innovative opportunities for insurers to better understand, serve, and connect with policyholders—as well as insulate companies against client attrition to lower-priced competitors. Indeed, if an insurer can demonstrate how repurposing data collected for insurance considerations might help a carrier offer valuable ancillary non-insurance services, customers may be more likely to opt in to share further data, more closely binding insurer and customer.

Leveraging IoT technologies may also have the peripheral advantage of resuscitating the industry’s brand, making insurance more enticing to the relatively small pool of skilled professionals needed to put these strategies in play. And such a shift would be welcome, considering that Deloitte’s Talent in Insurance Survey revealed that the tech-savvy Millennial generation generally considers a career in the insurance industry “boring.”4 Such a reputational challenge clearly creates a daunting obstacle for insurance executives and HR professionals, particularly given the dearth of employees with necessary skill sets to successfully enable and systematize IoT strategies, set against a backdrop of intense competition from many other industries. Implementing cutting-edge IoT strategies could boost the “hip factor” that the industry currently lacks.

With change comes challenges

While most stakeholders might see attractive possibilities in the opportunity for behavior monitoring across the insurance ecosystem, inevitable hurdles stand in the way of wholesale adoption. How insurers surmount each potential barrier is central to successful evolution.

For instance, the industry’s historically conservative approach to innovation may impede the speed and flexibility required for carriers to implement enhanced consumer strategies based on IoT technology. Execution may require more nimble data management and data warehousing than currently in place, as engineers will need to design ways to quickly aggregate, analyze, and act upon disparate data streams. To achieve this speed, executives may need to spearhead adjustments to corporate culture grounded in more centralized location of data control. Capabilities to discern which data are truly predictive versus just noise in the system are also critical. Therefore, along with standardized formats for IoT technology,5 insurers may see an increasing need for data scientists to mine, organize, and make sense of mountains of raw information.

Insurers may see an increasing need for data scientists to mine, organize, and make sense of mountains of raw information.

Perhaps most importantly, insurers would need to overcome the privacy concerns that could hinder consumers’ willingness to make available the data on which the IoT runs. Further, increased volume, velocity, and variety of data propagate a heightened need for appropriate security oversight and controls.

For insurers, efforts to capitalize on IoT technology may also require patience and long-term investments. Indeed, while bolstering market share, such efforts could put a short-term squeeze on revenues and profitability. To convince wary customers to opt in to monitoring programs, insurers may need to offer discounted pricing, at least at the start, on top of investments to finance infrastructure and staff supporting the new strategic initiative. This has essentially been the entry strategy for auto carriers in the usage-based insurance market, with discounts provided to convince drivers to allow their performance behind the wheel to be monitored, whether by a device installed in their vehicles or an application on their mobile device.

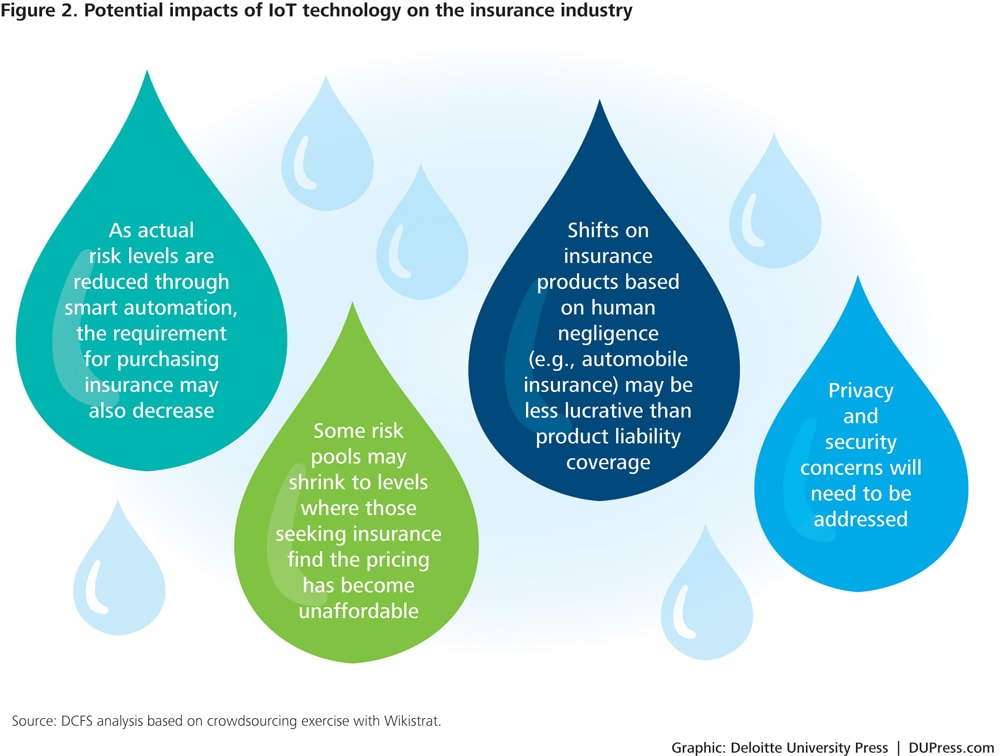

Results from the Wikistrat crowdsourcing simulation reveal several other IoT-related challenges that respondents put forward. (See figure 2.)6

Each scenario implies some measure of material impact to the insurance industry. In fact, together they suggest that the same technology that could potentially help improve loss ratios and strengthen policyholder bonds over the long haul may also make some of the most traditionally lucrative insurance lines obsolete.

For example, if embedding sensors in cars and homes to prevent hazardous incidents increasingly becomes the norm, and these sensors are perfected to the point where accidents are drastically reduced, this development may minimize or eliminate the need for personal auto and home liability coverage, given the lower frequency and severity of losses that result from such monitoring. Insurers need to stay ahead of this, perhaps even eventually shifting books of business from personal to product liability as claims evolve from human error to product failure.

Examining the IoT through an insurance lens

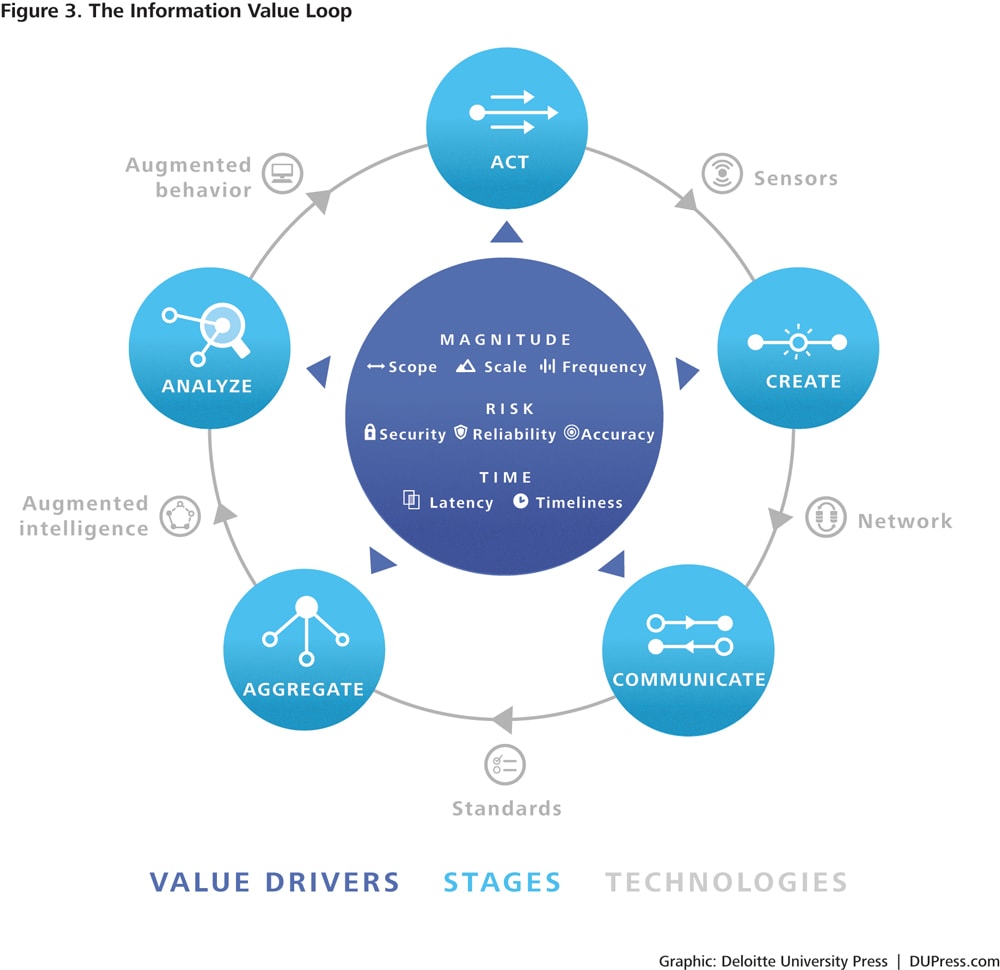

Analyzing the intrinsic value of adopting an IoT strategy is fundamental in the development of a business plan, as executives must carefully consider each of the various dimensions to assess the potential value and imminent challenges associated with every stage of operationalization. Using Deloitte’s Information Value Loop can help capture the stages (create, communicate, aggregate, analyze, act) through which information passes in order to create value.7

The value loop framework is designed to evaluate the components of IoT implementation as well as potential bottlenecks in the process, by capturing the series and sequence of activities by which organizations create value from information (figure 3).

To complete the loop and create value, information passes through the value loop’s stages, each enabled by specific technologies. An act is monitored by a sensor that creates information. That information passes through a network so that it can be communicated, and standards—be they technical, legal, regulatory, or social—allow that information to be aggregated across time and space. Augmented intelligence is a generic term meant to capture all manner of analytical support, collectively used to analyze information. The loop is completed via augmented behavior technologies that either enable automated, autonomous action or shape human decisions in a manner leading to improved action.8

For a look at the value loop through an insurance lens, we will examine an IoT capability already at play in the industry: automobile telematics. By circumnavigating the stages of the framework, we can scrutinize the efficacy of how monitoring driving behavior is poised to eventually transform the auto insurance market with a vast infusion of value to both consumers and insurers.

Auto insurance and the value loop

Telematic sensors in the vehicle monitor an individual’s driving to create personalized data collection. The connected car, via in-vehicle telecommunication sensors, has been available in some form for over a decade.9 The key value for insurers is that sensors can closely monitor individual driving behavior, which directly corresponds to risk, for more accuracy in underwriting and pricing.

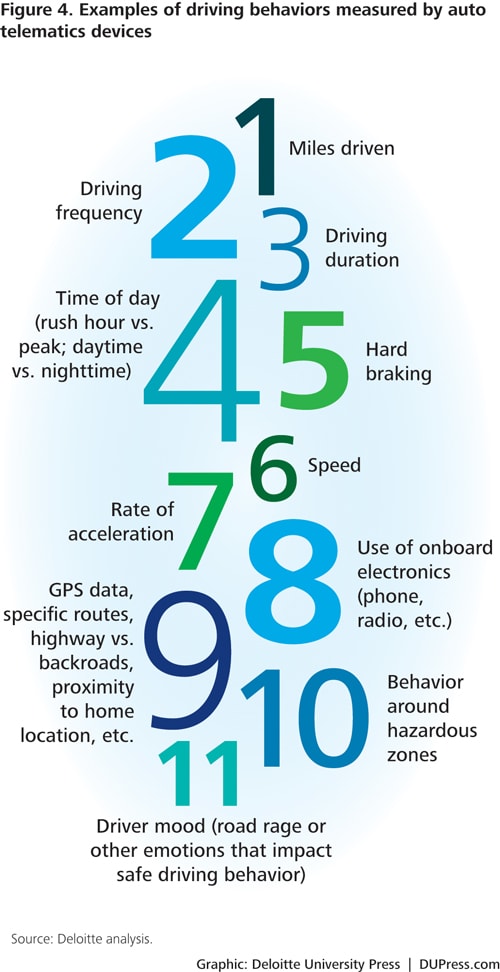

Originally, sensor manufacturers made devices available to install on vehicles; today, some carmakers are already integrating sensors into showroom models, available to drivers—and, potentially, their insurers—via smartphone apps. The sensors collect data (figure 4) which, if properly analyzed, might more accurately predict the unique level of risk associated with a specific individual’s driving and behavior. Once the data is created, an IoT-based system could quantify and transform it into “personalized” pricing.

Sensors’ increasing availability, affordability, and ease of use break what could potentially be a bottleneck at this stage of the Information Value Loop for other IoT capabilities in their early stages.

IoT technology aggregates and communicates information to the carrier to be evaluated. To identify potential correlations and create predictive models that produce reliable underwriting and pricing decisions, auto insurers need massive volumes of statistically and actuarially credible telematics data.

In the hierarchy of auto telematics monitoring, large insurers currently lead the pack when it comes to usage-based insurance market share, given the amount of data they have already accumulated or might potentially amass through their substantial client bases. In contrast, small and midsized insurers—with less comprehensive proprietary sources—will likely need more time to collect sufficient data on their own.

To break this bottleneck, smaller players could pool their telematics data with peers either independently or through a third-party vendor to create and share the broad insights necessary to allow a more level playing field throughout the industry.

Insurers analyze data and use it to encourage drivers to act by improving driver behavior/loss costs. By analyzing the collected data, insurers can now replace or augment proxy variables (age, car type, driving violations, education, gender, and credit score) correlated with the likelihood of having a loss with those factors directly contributing to the probability of loss for an individual driver (braking, acceleration, cornering, and average speed, as figure 4 shows). This is an inherently more equitable method to structure premiums: Rather than paying for something that might be true about a risk, a customer pays for what is true based on his own driving performance.

But even armed with all the data necessary to improve underwriting for “personalized” pricing, insurers need a way to convince millions of reluctant customers to opt in. To date, insurers have used the incentive of potential premium discounts to engage consumers in auto telematics monitoring.10 However, this model is not necessarily attractive enough to convince the majority of drivers to relinquish a measure of privacy and agree to usage-based insurance. It is also unsustainable for insurers that will eventually have to charge rates actually based on risk assessment rather than marketing initiatives.

Substantiating the point about consumer adoption is a recent survey by the Deloitte Center for Financial Services of 2,193 respondents representing a wide variety of demographic groups, aiming to understand consumer interest in mobile technology in financial services delivery, including the use of auto telematics monitoring. The survey identified three distinct groups among respondents when asked whether they would agree to allow an insurer to track their driving experience, if it meant they would be eligible for premium discounts based on their performance (figure 5).11 While one-quarter of respondents were amenable to being monitored, just as many said they would require a substantial discount to make it worth their while (figure 5), and nearly half would not consent.

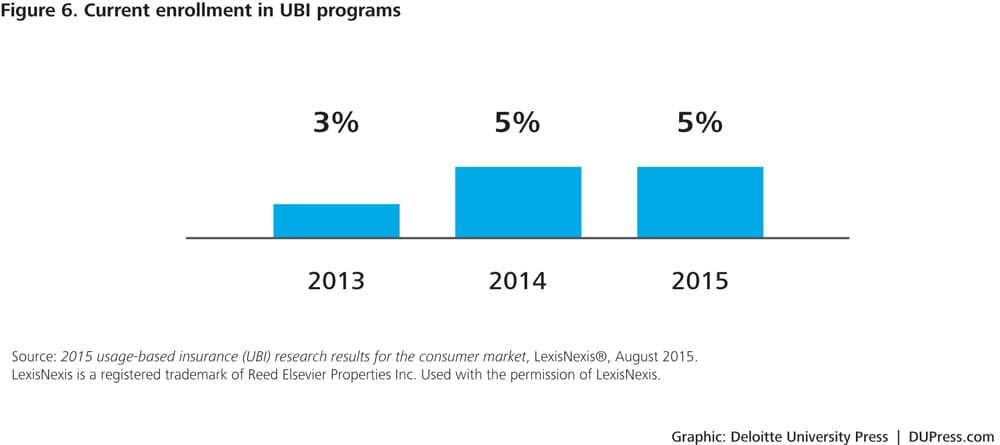

While the Deloitte survey was prospective (asking how many respondents would be willing to have their driving monitored telematically), actual recruits have been proven to be difficult to bring on board. Indeed, a 2015 Lexis-Nexis study on the consumer market for telematics showed that usage-based insurance enrollment has remained at only 5 percent of households from 2014 to 2015 (figure 6).12

Both of these survey results suggest that premium discounts alone have not and likely will not induce many consumers to opt in to telematics monitoring going forward, and would likely be an unsustainable model for insurers to pursue. The good news: Research suggests that, while protective of their personal information, most consumers are willing to trade access to that data for valuable services from a reputable brand.13 Therefore, insurers will likely have to differentiate their telematics-based product offerings beyond any initial early-adopter premium savings by offering value-added services to encourage uptake, as well as to protect market share from other players moving into the telematics space.

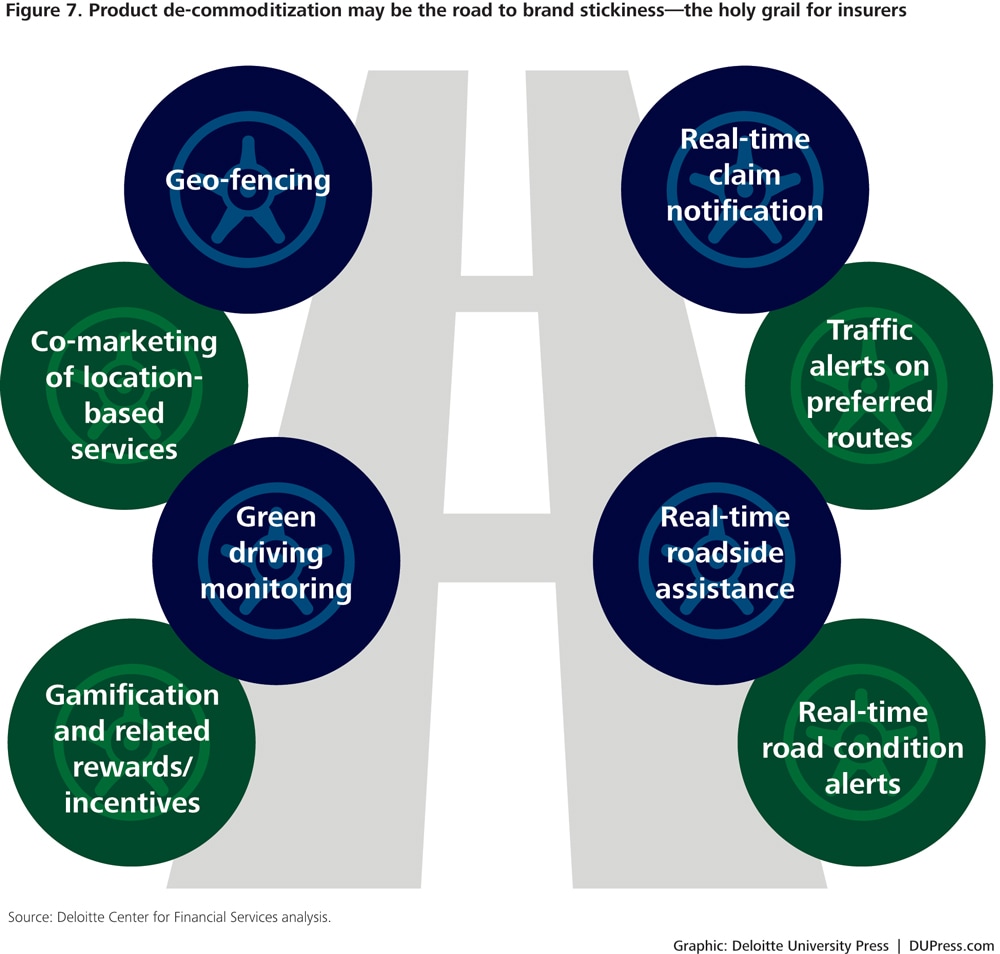

In other words, insurers—by offering mutually beneficial, ongoing value-added services—can use IoT-based data to become an integral daily influence for connected policyholders. Companies can incentivize consumers to opt in by offering real-time, behavior-related services, such as individualized marketing and advertising, travel recommendations based on location, alerts about potentially hazardous road conditions or traffic, and even diagnostics and alerts about a vehicle’s potential issues (figure 7).14 More broadly, insurers could aim to serve as trusted advisers to help drivers realize the benefits of tomorrow’s connected car.15

Many IoT applications offer real value to both insurers and policyholders: Consider GPS-enabled geo-fencing, which can monitor and send alerts about driving behavior of teens or elderly parents. For example, Ford’s MyKey technology includes tools such as letting parents limit top speeds, mute the radio until seat belts are buckled, and keep the radio at a certain volume while the vehicle is moving.16 Other customers may be attracted to “green” monitoring, in which they receive feedback on how environmentally friendly their driving behavior is.

Insurers can also look to offer IoT-related services exclusive of risk transfer—for example, co-marketing location-based services with other providers, such as roadside assistance, auto repairs, and car washes may strengthen loyalty to a carrier. They can also include various nonvehicle-related service options such as alerts about nearby restaurants and shopping, perhaps in conjunction with points earned by good driving behavior in loyalty programs or through gamification, which could be redeemed at participating vendors. Indeed, consumers may be reluctant to switch carriers based solely on pricing, knowing they would be abandoning accumulated loyalty points as well as a host of personalized apps and settings.

For all types of insurance—not just auto—the objective is for insurers to identify the expectations that different types of policyholders may have, and then adapt those insights into practical applications through customized telematic monitoring to elevate the customer experience.

Telematics monitoring has demonstrated benefits even beyond better customer experience for policyholders. Insurers can use telematics tools to expose an individual’s risky driving behavior and encourage adjustments. Indeed, people being monitored by behavior sensors will likely improve their driving habits and reduce crash rates—a result to everyone’s benefit. This “nudge effect” indicates that the motivation to change driving behavior is likely linked to the actual surveillance facilitated by IoT technology.

The power of peer pressure is another galvanizing influence that can provoke beneficial consumer behavior. Take fitness wearables, which incentivize individuals to do as much or more exercise than the peers with whom they compete.17 In fact, research done in several industries points to an individual’s tendency to be influenced by peer behavior above most other factors. For example, researchers asked four separate groups of utility consumers to cut energy consumption: one for the good of the planet, a second for the well-being of future generations, a third for financial savings, and a fourth because their neighbors were doing it. The only group that elicited any drop in consumption (at 10 percent) was the fourth—the peer comparison group.18

Insurers equipped with not only specific policyholder information but aggregated data that puts a user’s experience in a community context have a real opportunity to influence customer behavior. Since people generally resist violating social norms, if a trusted adviser offers data that compares customer behavior to “the ideal driver”—or, better, to a group of friends, family, colleagues, or peers—they will, one hopes, adapt to safer habits.

The future ain’t what it used to be—what should insurers do?

After decades of adherence to traditional business models, the insurance industry, pushed and guided by connected technology, is taking a road less traveled. Analysts expect some 38.5 billion IoT devices to be deployed globally by 2020, nearly three times as many as today,19 and insurers will no doubt install their fair share of sensors, data banks, and apps. In an otherwise static operating environment, IoT applications present insurers with an opportunity to benefit from technology that aims to improve profits, enable growth, strengthen the consumer experience, build new market relevance, and avoid disruption from more forward-looking traditional and nontraditional competitors.

Incorporating IoT technology into insurer business models will entail transformation to elicit the benefits offered by each strategy.

- Carriers must confront the barriers associated with conflicting standards—data must be harvested and harnessed in a way that makes the information valid and able to generate valuable insights. This could include making in-house legacy systems more modernized and flexible, building or buying new systems, or collaborating with third-party sources to develop more standardized technology for harmonious connectivity.

- Corporate culture will need a facelift—or, likely, something more dramatic—to overcome longstanding conventions on how information is managed and consumed across the organization. In line with industry practices around broader data management initiatives,20 successfully implementing IoT technology will require supportive “tone at the top,” change management initiatives, and enterprisewide training.

- With premium savings already proving insufficient to entice most customers to allow insurers access to their personal usage data, companies will need to strategize how to convince or incentivize customers to opt in—after all, without that data, IoT applications are of limited use. To promote IoT-aided connectivity, insurers should look to market value-added services, loyalty points, and rewards for reducing risk. Insurers need to design these services in conjunction with their insurance offerings, to ensure that both make best use of the data being collected.

- Insurers will need to carefully consider how an interconnected world might shift products from focusing on cleaning up after disruptions to forestalling those disruptions before they happen. IoT technology will likely upend certain lines of businesses, potentially even making some obsolete. Therefore, companies must consider how to heighten flexibility in their models, systems, and culture to counterbalance changing insurance needs related to greater connectivity.

- IoT connectivity may also potentially level the playing field among insurers. Since a number of the broad capabilities that technology is introducing do not necessarily require large data sets to participate (such as measuring whether containers in a refrigerated truck are at optimal temperatures to prevent spoilage21 or whether soil has the right mix of nutrients for a particular crop22), small to midsized players or even new entrants may be able to seize competitive advantages from currently dominant players.

- And finally, to test the efficacy of each IoT-related strategy prior to implementation, a framework such as the Information Value Loop may become an invaluable tool, helping forge a path forward and identify potential bottlenecks or barriers that may need to be resolved to get the greatest value out of investments in connectivity.

The bottom line: IoT is here to stay, and insurers need look beyond business as usual to remain competitive.

The IoT is here to stay, the rate of change is unlikely to slow anytime soon, and the conservative insurance industry is hardly impervious to connectivity-fueled disruption—both positive and negative. The bottom line: Insurers need to look beyond business as usual. In the long term, no company can afford to engage in premium price wars over commoditized products. A business model informed by IoT applications might emphasize differentiating offerings, strengthening customer bonds, energizing the industry brand, and curtailing risk either at or prior to its initiation.

IoT-related disruptors should also be considered through a long-term lens, and responses will likely need to be forward-looking and flexible to incorporate the increasingly connected, constantly evolving environment. With global connectivity reaching a fever pitch amid increasing rates of consumer uptake, embedding these neoteric schemes into the insurance industry’s DNA is no longer a matter of if but, rather, of when and how.

Deloitte’s Internet of Things practice enables organizations to identify where the IoT can potentially create value in their industry and develop strategies to capture that value, utilizing the IoT for operational benefit.

Learn more about Deloitte's IoT practice.

Visit the full Internet of Things collection.