No time to retire Redesigning work for our aging workforce

17 minute read

07 December 2018

To capitalize on a new talent pool—not millennials, but those who continue to work past traditional retirement age—leaders should understand who these workers are, what motivates them, and the opportunities they present.

The aging of populations represents the most profound change that is guaranteed to come to high-income countries everywhere and most low-and middle-income ones as well.—Joseph Coughlin, founder of the MIT Age Lab1

Today’s fastest-growing workforce segment is taking organizations by storm—wanting flexibility, equal opportunities, and better access to training and development. They are asking for deeper meaning in their work and looking to make societal impacts that transcend their own footprint. And no, we are not talking about millennials. We are talking about employees working well into their 70s, forging their way into uncharted territory and redefining what it means to be an aging worker.

The current volume and rapid increase of people remaining in the workplace well past traditional retirement age is unprecedented. For the last two centuries, life expectancy has increased by about three years every decade, according to the authors of The 100-Year Life, Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott. This is pushing many to extend their working years.2 While overall, the United States labor market is projected to grow at an average rate of 0.6 percent per year between 2016 and 2026, the 65–74 age group is projected to grow by 4.2 percent each year, and the 75+ worker group is projected to grow by 6.7 percent annually.3 This trend is tilting overall workforce demographics toward the high end of the age spectrum, and the impacts of the aging workforce can already be seen at the individual, organizational, and societal level.4

Learn More

Read more from the Future of Work collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights app

Some leaders, attuned to attracting and retaining top talent regardless of age, are actively redesigning their workplaces to accommodate the diversity of needs across a five-generation workplace. But many other organizations are dramatically underprepared for this large shift. To navigate this generally requires an understanding of who these workers are, their needs and motivations, and the business opportunities this trend presents. In this article, we’ll explore these topics as well as how organizations can create meaningful jobs that work with and for this valuable talent pool.

Hiding in plain sight: Understanding the roots of our aging population

Recent research released by the US Department of Labor shows that, by 2024, one in four workers in the United States will be 55 or older. To put this in context, in 1994, workers over the age of 55 accounted for about one in 10 workers.5

This sharp increase in older workers was entirely predictable. The baby boom generation—those born between the mid-1940s through the mid-1960s—received its name due to its sheer size.6 People started to take notice of the implications as early as 1989, when Dr. Ken Dychtwald’s book, Age Wave, described the aging American population as a sleeping giant, just then “awakening to its social and political power.” 7 But what has made this trend particularly pronounced today is that average life expectancy has also increased by 50 percent in the last 100 years.8 With this large of a generation experiencing such a massive increase in longevity, it’s no surprise that we are also seeing changes in the way people think about work, retirement, and age itself.

But longer life is not without its challenges. Many individuals are not financially prepared for retirement. Only 24 percent of today’s US workers aged 55+ have saved more than US$250,000 (excluding homes and pensions).9 The need for work may never be as strong as it is now for baby boomers, still supporting their families, recovering from a recession, and trying to save enough for a 100-year lifespan.

Even for those with the means to retire, Jonathan Rauch, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, observes: “People are getting to their sixties with another 15 years of productive life ahead, and this is turning out to be the most emotionally rewarding part of life. They don’t want to hang it up and just play golf. That model is wrong.”10

As a result, either by choice or by need, 85 percent of today’s baby boomers plan to continue to work into their 70s and even 80s.11 And so, for the first time, societies, organizations, and individuals are grappling with the implications of this and how to handle it. The sleeping giant that Age Wave predicted nearly 30 years ago is fully awake, ready to upend our existing paradigms of age and work. And the need to redesign our workplaces to accommodate this has never seemed more urgent.12

The aging workforce: A business leader’s bookshelf

In the past 30 years, a great deal has been written about the aging workforce. Four key books frame much of this literature:

Age Wave by Ken Dychtwald, PhD

Based on 15 years of research by a leading researcher on aging, this book gives one of the first wide-ranging analyses of the consequences of the aging baby-boomer population on society.

The 100-Year Life by Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott

Drawing on the unique pairing of psychology and economics, this book offers an analysis to help us all rethink retirement, finances, education, careers, and relationships to create a fulfilling 100-year life.

Encore by Marc Freedman

Encore tells the stories of baby boomer career pioneers who are not content, or affluent enough, to spend their next 30 years on a golf course.

The Longevity Economy by Joseph F. Coughlin

Coughlin challenges myths about aging with groundbreaking multidisciplinary research into what older people actually want—not what conventional wisdom suggests they need.

The business case for mature workers

Public policy leaders are pushing to ensure that older workers are “able to thrive at work and adequately prepare for retirement.”13 While many organizational leaders are aware of the trend toward an aging workforce, few say they are acting. A 2016 survey of human resource professionals by the Society for Human Resource Management revealed just 17 percent of organizations have considered the trend’s longer-term impacts over the next decade.14

Part of this inaction is fueled by inaccurate views on the value of aging workers. In Deloitte’s 2018 Global Human Capital Trends report, nearly half of the respondents surveyed (49 percent) said that their organizations have done nothing to help older workers find new careers as they age. Rather than seeing opportunity, 20 percent of respondents viewed older workers as a competitive disadvantage, and in countries such as Singapore, the Netherlands, and Russia, this percentage was far higher. In fact, 15 percent of respondents believed that older employees were “an impediment to rising talent” by getting in the way of up-and-coming younger workers.

And so, the looming question, often fueled by these inaccurate views of older workers’ capabilities, is: Why would a business pursue older workers? What are the potential benefits to workplace culture and the bottom line? It turns out, there are many.

Engagement and grit levels increase with age

Engagement levels tend to increase with age, likely because older workers have had the time to find roles that suit their skills and career preferences.15 Of course, not all baby boomers are in their preferred roles, but the data shows that compared to other generations, they tend to persist longer and have more engagement in their work.16 Traditionalists (born prior to 1945) still in the workforce have the highest levels of engagement, but baby boomers seem to be closing that gap as the years go by.17 Fairly consistently across studies, millennials tend to show the lowest engagement levels.18 This may be no surprise, as many younger workers are not yet in their preferred roles and are still working their way through entry-level or lower-management-level roles.

Just how important is engagement? According to a 2016 Gallup study, when comparing groups in the top quartile of engagement with the bottom quartile, the engaged worker groups performed better across a variety of important business metrics, yielding 21 percent higher profitability, 40 percent higher quality, and 10 percent stronger customer loyalty, and performing 70 percent better in terms of safety.19 In aggregate, highly engaged workers typically perform twice as well as those who are disengaged across a range of metrics.20

Experienced workers can help fill the talent gap

The growing labor shortage has been a topic of discussion for many years, and we seem to be reaching a critical point as baby boomers choosing to retire leave the workforce. In July 2018, ADP and Moody’s Analytics reported that the United States added only 177,000 jobs in June, though Thomson Reuters expected a gain of 190,000.21 “Business’s No. 1 problem is finding qualified workers,” Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, said in a statement for CNBC. “At the current pace of job growth, if sustained, this problem is set to get much worse. These labor shortages will only intensify across all industries and company sizes.”22

Experience is a critical asset right now, and one that older workers have accumulated over the course of their lives and careers. According to author David DeLong, this experience makes older workers more likely to possess three types of knowledge in particular: human, social, and cultural. Human knowledge relates to skills or expertise specific to a role, such as a legacy system or tools, while social knowledge relates to relationship skills. Cultural knowledge is a combination—it is the understanding of how things actually get done in an organization.23

Work quality improves with age

While stereotypes about age-related rigidity and cognitive decline abound, research shows that age and core task performance are largely unrelated.24 In fact, certain skills that can help older workers provide unique value to their organizations, such as social skills, can actually improve as we age.25 In addition, studies have also shown that older workers can be just as creative and innovative as younger employees.26 And while speed and the ability to multitask tend to decline after age 55, mature workers often display a great deal of wisdom, which can lead them to make more realistic judgments than some younger people do.27

These dueling positive and negative effects associated with aging seem to produce a consistent net effect: While older workers may be somewhat slower to complete some tasks, their work product tends to be of higher quality than that of younger workers.28

Mature workers tend to display stronger relationship skills and organizational citizenship behaviors

Outside an employee’s core tasks, there is a long list of behaviors that can promote how well your business functions—for example, showing up to work on time, displaying a positive attitude, complying with organizational norms and safety standards, and listening to instructions. All these things fall into the category of organizational citizenship.

Research has shown that older workers are more likely than younger workers to demonstrate positive organizational citizenship. In other words, they tend to show up on time, avoid gossip, help their teammates, and keep their frustrations in check.29 They are also recognized for attributes such as loyalty, reliability, a strong work ethic, high skill levels, and strong professional networks.30

Older workers can help companies gain older customers

The population is aging not only in our workplaces, but also in the market generally—and older individuals tend to have a lot of spending power. In the United States alone, people aged 50+ spent more than US$5.6 trillion in 2015—well above the US$4.9 trillion spent by those under age 50, and accounting for nearly half of the country’s GDP for that year.

By maintaining representation of this customer base within the workforce, an organization can improve its ability to engage with and even create new products and services for older buyers. As the saying goes, “nothing about us, without us;” in other words, to serve a population well, it’s best to have members of that population involved.

Six personas: Understanding the aging workforce

Who exactly is the aging workforce? What are their stories, their motivations, and their work arrangements within organizations?

To help bring greater clarity to who these people are, we have developed six personas based on recent research to help management understand, attract, and retain the 60+ talent pool in their workplaces. In figure 1, we have plotted these six personas based on their primary motive for work, and if they continue on with their same employer. We also show our estimates of what percentage of the aging workforce falls within each of these categories.

About the research

To help quantify the impact the aging workforce is having within organizations and their preferred working style, we conducted a year-long literature review by turning to academic literature, government resources, and statistical data to determine the personas themselves as well as identify the data behind figure 1. The following resources were used during the literature review process: US Labor Bureau of Statistics, United States Senate Committee report on America’s aging workforce: Opportunities and challenges, The Longevity Economy, The 100-Year life, The Encore Career, and multiple academic research articles from the Journal of Applied Psychology, Society of Human Resource Management, and Gallup. Each of these articles and resources provided insights into the different types of work emerging for this generation, with four specific themes arising from the qualitative coding analysis. Workers either stayed within their own organization to reach retirement or more commonly sought employment elsewhere. The other two themes were that workers chose to stay within the workforce primarily due to financial reasons—such as needing more money for retirement or access to benefits—or their primary concern was personal. These reasons may have included caring for an ailing parent or partner, requiring more time to pursue a hobby or interest, or simply wanting more autonomy over their remaining years. We were then able to plot these themes into figure 1 and make approximate estimates on what percentage of the aging workforce fell into the respective categories.

Bridge worker

Summary:

- Percentage: ~25–30 percent (largest percentage of aging workers)

- Motivation: Primarily financial

- Strengths: Often an experienced worker with strong work ethic and emotional regulation

- Goals: Financial savings, benefits, may desire flexible hours

Jerry, a corporate trainer in the New England area, met with his financial advisors at age 50 and expressed a desire to retire by the time he was 60. But there was a problem with his plan. He still had to put two kids through college and couldn’t obtain the raises he anticipated as a result of the economic slowdown. The financial advisors suggested a more realistic retirement age of 70, and they were right. Jerry is now 65 and sees at least another 5 to 7 years of work in his future. The problem? His organization restructured, leaving him with a yearlong severance package, but no work. He quickly shopped his resume around, but had trouble securing a full-time job within his industry. After a six-month job search turned up dry, Jerry turned to local retail shops within his community. A hardware store offered him a part-time job with benefits. Jerry accepted and now sees the next few years as bridge years toward retirement. With the cost of living on the rise, Jerry may need to hold onto this job well into his early 70s before entering full-time retirement. But it helps pay the bills without dipping into his savings, which is Jerry’s primary concern at the moment.

Tenured worker (phased retirement)

Summary:

- Percentage: ~15–20 percent

- Motivation: Often to leave a legacy and pass on implicit knowledge to others in the organization

- Strengths: Institutional knowledge of organization, often serves as a strong mentor

- Goals: Mentorship, stability easing into retirement, successful transition of work

Susan, age 64, has worked her entire life in the health care industry, starting as a nurse nearly 40 years ago and transitioning into hospital administration halfway through her career. She is now the COO of one of the nation’s largest health care systems. Susan has always had a knack for not only maintaining high customer service standards while identifying the most efficient and effective way to do so. But she is now looking to shift the pace of work to better match her lifestyle. Now that she is nearly 65, she wants to spend more time with her family, travel, and even take up a new hobby. However, she isn’t quite yet ready to let go of her work and the legacy she has spent her entire working life building. Susan met with the CEO and board of directors and expressed her desire to stay within her position but begin to build a longer-term succession plan that would result in her rolling off in the next three years. This would give her enough time to bring a successor up to speed, and also allow her to begin the transition to her next phase of life. The CEO is thankful for the transition period and Susan is grateful for a phased approach to retirement.

Gig worker

Summary:

- Percentage: ~5–7 percent

- Motivation: Social interaction, flexible hours

- Strengths: Relational skills and free capacity to engage in gig work

- Goals: Extra spending money and flexibility

Tom spent nearly 40 years as a corporate executive in the financial services industry. His career was marked by much success, as he advised clients on the numbers behind potential mergers and acquisitions. But after the financial crisis, at age 62, he was forced into early retirement. Being financially savvy, Tom was well ahead of his peers when it came to his retirement fund, so he decided to take a year off and move closer to his grandchildren. He spent a lot of time on the road during his career and didn’t want to miss out on his grandchildren growing up. But after a year, Tom found himself with too much time on his hands and not enough connection with the outside world. His adult children talked him into joining a freelancing platform as a gig worker. Tom could work only when he wanted to, have a chance to connect with others, and share the skills he built over his career, not to mention making some extra spending money for that family cruise he was planning. This gig work would allow him the flexibility and connection he was looking for postcareer. It’s not the money, he explains, but the flexibility and opportunity to connect with others that keeps him going.

Self-employment

Summary:

- Percentage: ~9–12 percent

- Motivation: Fulfilling an unrealized dream or maintaining an existing business

- Strengths: Entrepreneurialism, career experience

- Goals: Autonomy, ownership

Steve and Nancy, both aged 55, had always wanted to start a small business together. It was this shared passion to own a business that first attracted them to each other nearly 25 years ago. But, three kids later, mortgage payments and yearly vacations had put the dream to own a business on the back burner. However, now it seems the timing might be right. Nancy has just left her job as a high school teacher with a state pension in hand to care for her ailing mom. Meanwhile, Steve, who has worked in nearly half a dozen manufacturing organizations as an engineer, is being offered the opportunity to buy the business from his latest employer. Steve and Nancy still plan to work at least another 15 years, and they think it is finally time to work for themselves. It will certainly be a financial risk that may result in their having to work longer than anticipated, but one they are willing to take for the chance to own a business.

Alumni worker (un-retirement)

Summary:

- Percentage: ~20 percent

- Motivation: Meaningful work, many need flexible hours

- Strengths: Institutional knowledge, strong relational networks

- Goals: Flexibility, passing along tacit organizational knowledge, play a consulting or mentoring role

Sam, approaching age 60, loved his company. But after having worked there for nearly 15 years, he decided it was time to take a much-needed break. Sam had developed a disability and needed time to address his overall health. In his departure announcement, he did not mention the disability, but simply expressed a need to take a step back and reprioritize his schedule. His organization felt Sam’s departure within months. Processes that had seemed to flow effortlessly began breaking down, and the staff previously working under Sam was relatively junior and didn’t have the legacy knowledge required to fix the breakdowns. Clients began asking for refunds due to the poor quality of services. In the meantime, Sam was actively seeking out a part-time arrangement within the industry. He still wanted to stay engaged, but needed work that would allow for his doctor’s appointments and accommodate his disability. His old company asked Sam if he would consider coming back on as an alumni worker. They needed him to help transfer the legacy knowledge and relationships that he had spent nearly two decades building. And, he could set his own hours. Sam was thrilled. He could work part-time hours and yet make an immediate impact to the organization he had developed such an affinity for.

Encore worker

Summary:

- Percentage: ~9–12 percent

- Motivation: Meaningful work, social interaction

- Strengths: Life experience, passion

- Goals: Social change

A group of former engineers recently got together over breakfast to share their “life after work” stories.32 Each of the four women, aged between 59 and 63, recently retired and all were trying to adjust to new routines. While none of them wanted to work for a large organization again, they did miss making an impact, and deeply desired to do so again. During breakfast, they discussed how their own local Southern community was in dire need of improvement. There was a block of abandoned homes that needed to be brought back to code for them to be occupied again. Meanwhile, the homeless shelter was used beyond capacity. This group of former engineers realized they had the know-how and the capacity to fix up these homes. They formed a group, known as the Shingle Ladies, who spent their free time fixing up homes in their community. For the four founders, running and participating in the group was their encore career, and they couldn’t be happier applying their skills to make a difference in newfound ways.

Each of these personas are meant to illustrate the countless workers across our nation seeking to engage in careers well past the age of 55. Additional research surrounding motivations can be found in the sidebar, What motivates the aging workforce? Organizations seeking to capture the value within one of the fastest-growing workforce segments should account for all their different styles, preferences, and motivators as illustrated in the personas above.

What motivates the aging workforce?

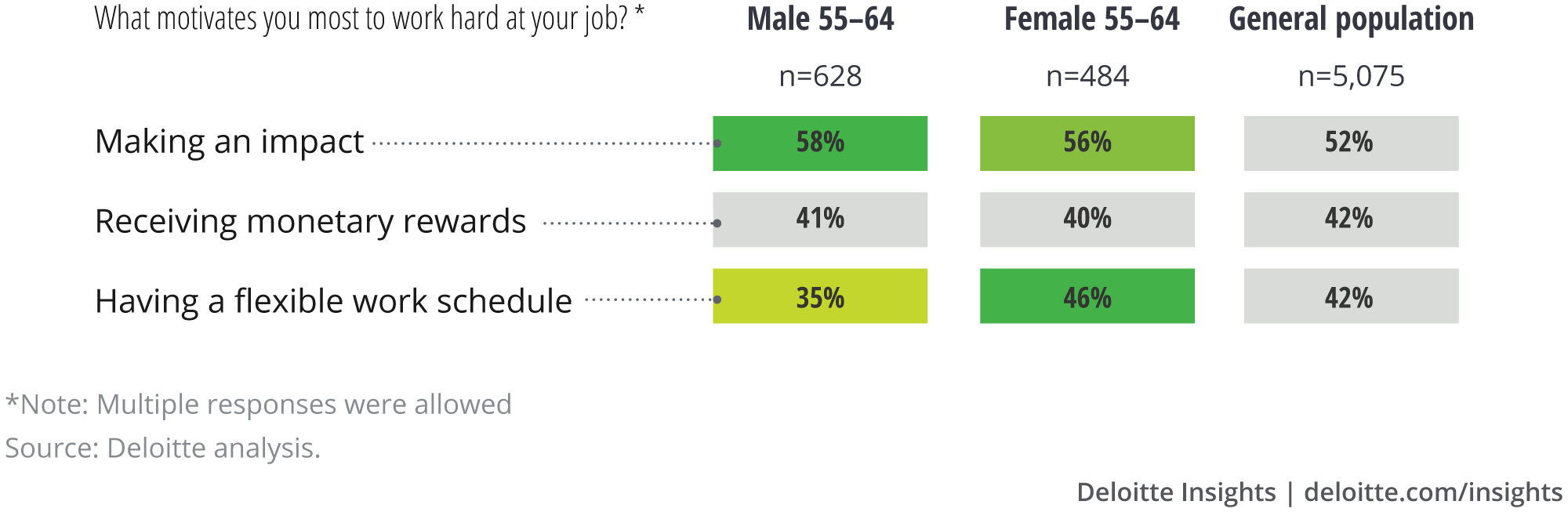

Understanding worker motivation could be key to unlocking productivity in your organization. We fielded a US-based survey to over 5,000 workers asking about their beliefs, motivations, and expectations of work. Three motivators appeared to emerge as key to working hard in a job—but the degree to which it showed up in the data seemed to differ in the aging population.

Upgrading your organizations to attract and retain older workers

Aging workers come with a lot of potential value for a business. So, to create a mutually beneficial relationship, organizations will likely need to make some shifts to both attract and empower this talent pool to do their most valuable and rewarding work.

Within the future of work research conducted at Deloitte, we look at the way various trends are having an impact on the redesign of work, the workforce itself, and the workplace. Here are three considerations for redesigning the work and workplace to attract the growing workforce in your organization.

Redesign work to capture values and strengths of older workers

Much like other generations in the workforce, most of the aging population is seeking work that makes a difference and matters. They are looking to share their decades of experience and knowledge with others in the organization. Redesign work to leverage the power of this workforce’s tacit knowledge and seek to capture as much value as possible through mentorship and apprenticeship programs. Encourage older workers to work alongside younger employees as advised earlier in Gen Z enters the workforce to help facilitate successful industry knowledge transfer that can be otherwise hard to obtain.33 More than 80 percent of millennials are looking for on-the-job training opportunities, and list it as the most valuable element in helping them to perform their best, according to Deloitte’s 2018 Millennial Survey.34 To do this effectively, certain functions and teams can be structured around the unique characteristics and strengths of older workers, such as wisdom and judgment, and social and legacy knowledge—beyond mentoring, roles in customer service or support can benefit immensely from this. As much as possible, consider redesigning work away from routine and repetitive tasks and into mentoring relationships to capture the value of an aging workforce.

Intentionally design phased retirement programs to allow for greater flexibility

Within our research, we found that many workers aged 55+ are also acting as a caregiver for a loved one or dealing with their own disability. This additional pressure to make health care appointments and caregiving responsibility outside of work requires even more flexibility than what is often given. While many organizations agree that flexibility is important, few have acted to set policies in place.35 Organizations should seek to extend flexible schedules and remote work options to ensure their institutional knowledge and transition of the business work is successfully passed onto the next generation of workers. Supporting the migration of older workers into your gig or contingent worker network can be an excellent way to keep them connected, while giving them the flexible work schedules they are looking for.

Ensure the physical location of the workplace is accessible for your older workers

An easy-to-overlook element of becoming a destination of choice for an aging worker is to ensure that the setup of their work considers the physical impact it might have. For example, one of the largest factories for a car manufacturer relied heavily on workers aged 50+. Much of their workforce had been with the company for decades and represented a real risk if they left the business. However, the physical labor was creating an early exit for some of the workers. The company seeking to address this concern launched a wellness program to specifically target the well-being of its aging workforce. They instituted a total of over 70 specific changes to the workplace environment—such as ergonomic furniture, adaptable seats, new factory flooring that made it easier to stand, special shoes, and better computer monitors. In addition, the company just didn’t stop at the physical but also sought to engage their older workers by actively rotating them throughout multiple jobs to better stimulate them throughout the day.

Offer creative ways to reskill aging workers for the needs of your company

Aging workers bring a lot of valuable and transferable social and organizational skills. But to be fully ready for the needs of today’s workforce, they may need some degree of training. Think of creative ways to help onboard them into your organization—apprenticeship is one model that has seen a lot of success. One financial organization wanted to help older workers stay in the workforce. Many older workers could struggle with longer spans of unemployment that might leave them feeling discouraged and that their skills are out of date. To tap into this valuable talent pool, the financial organization designed an apprenticeship program to help these workers bring their value to an organization again. The apprenticeship model not only helped to retrain people with new skill sets, but it provided a key element of confidence-building that made this program a success.36

The longevity dividend presents opportunities for business leaders from both the consumer and talent markets. As many organizations are actively in the process of redesigning their work, workforce, and workplace to better prepare for the future of work, let’s not overlook the fastest-growing segment of workers—the baby boomers—during that process. Attracting and retaining the aging population could be key to unleashing the future of work in your organization. Preparing programs to engage the range of older workers should be a priority and may be a differentiator in talent and workforce strategies. It’s time to shift into action.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.