What's next for bank board risk governance? has been saved

What's next for bank board risk governance? Recalibrating to tackle new risk oversight expectations

31 October 2017

As organizational risks continue to evolve and grow, bank boards need to step up their efforts to provide effective stewardship to anticipate and combat those threats. Here are some leading practices boards can employ to meet the new risk management demands.

Foreword

Dear colleague,

We are now about a decade removed from the defining days of the financial crisis. As the financial system stood on a precipice, the risk management and governance functions at most banks were challenged as never before. In the wake of the crisis, risk management and board oversight of risk became fundamental priorities for bank management teams and shareholders. The breadth and intensity of regulation, compliance requirements, and supervisory expectations increased exponentially, and bank executives and boards poured time and money to meet them.

In that sense, “All hands on deck!” may be the most appropriate characterization of how most banks responded. Institutions seem to have become more vigilant and resilient from a financial, process, and governance perspective. But the constant readjustment also led to a blurring of lines between the role and accountability of boards vis-à-vis senior management1—an observation that regulators now directly acknowledge.2 Board member responsibilities and obligations have substantively heightened, and the time and complexity associated with serving as a member of risk committees have soared.

In August 2017, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) proposed revisiting supervisory expectations of bank boards “to establish principles regarding effective boards of directors focused on the performance of a board’s core responsibilities,” with comment period for external input closing recently.3 The Fed’s proposal aimed at reviewing the role of boards to create stronger delineation between board member oversight responsibilities and management’s obligations and laid out new Board Effectiveness (BE) guidance. This followed the US Department of the Treasury’s June 2017 recommendation of an interagency review of requirements imposed on banks’ boards.4

These proposals can be considered positive for the banking industry. Board members have frequently found themselves being drawn “into the weeds” of risk management issues, and are sometimes left with inadequate time to guide and challenge management on broader strategic issues. The Fed’s proposal, therefore, heralds a fundamental rethinking of the way that boards prioritize their focus. Its delineation of board and management responsibilities also creates an environment in which senior executives and business line leaders can be unambiguously held accountable for their management responsibilities.

This paper, the fourth in our continuing series of studies on board risk governance, is a timely addition to the current discussion around the role of boards at large banks. It extends Deloitte’s5 effort, first started in 2009, to evaluate risk governance standards at the largest and most systemically important US and global institutions against regulatory requirements and an expanded array of leading practices.6

At a broader level though, as the nature of oversight expectations evolves, bank boards—particularly the board risk committee—will have to recalibrate to provide “effective challenge”7 to management on overall risk strategy and develop mechanisms to hold management accountable. Fulfilling these mandates is likely to be demanding and far from easy, yet the enormous progress that institutions have made in risk management and oversight over the past decade should leave them better prepared to step up to the challenge.

Scott Baret

Edward Hida

A sea change beckons

This fourth iteration of Deloitte’s series analyzing the charters of board of directors’ risk committees appears to confirm that systemically important US banks, their global peers, and US-based nonbank systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) have come a long way in their efforts to increase the level and breadth of their oversight of risk management. Since late 2014, when we last analyzed banks’ board risk committee charters, many institutions have made large gains in documenting compliance with expectations from the Federal Reserve’s Enhanced Prudential Standards (EPS), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s (OCC) Heightened Standards, and the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision’s (BCBS) guidelines on bank corporate governance.

However, evolution in the risk environment is creating new governance priorities, and articulating clear mandates around them is an all-important step; hence, despite significant progress, there is likely still work to be done.

Given a more complex and interconnected operating environment, most boards should prepare to question and evaluate the interplay of risks institutions are exposed to as a result of management’s business strategy, and probe risks to the bank’s chosen strategy. As a corollary, risk committees should challenge the capability of the risk management apparatus to identify, report, and remediate risks relating to strategy. In this respect, the role of risk oversight and governance goes beyond the notion of mere risk avoidance; it demonstrates how risk committees can help create and protect firm value.

Ironically, these demands for heightened risk awareness come just as regulatory expectations appear to be levelling off, after a decade of continuous escalation. A few far-reaching rules instituted after the downturn, such as the Volcker Rule, are even being reevaluated.8 And while regulatory compliance may still pose a major challenge, after considerable time and investment, most banks seem to have mastered certain aspects—all US banks passed the Fed’s 2017 Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review process, for example.9

In short, the risk committee should take a proactive role in: fully appreciating and understanding the nature of risks to which institutions are exposed; reevaluating or reconsidering the bank’s risk strategy and appetite in the context of these new and shifting risks; and reengineering mechanisms to assign accountability and oversee management’s execution of risk strategy and appetite. These imperatives seem to align with the recent Fed proposal’s guidance on the role of boards in defining risk strategy and in clearly holding management accountable.

In this paper, we present the results of our analysis of board risk committee charters, along with guidance for bank boards as they confront this evolving risk environment. While these charters are one yardstick to measure the level and quality of risk management oversight of a board’s risk committee, we acknowledge that theydo not necessarily equate to high performance (see sidebar, “An important caveat”). That said, we apply this methodology as transparent, public, and comprehensive documentation is a likely first step to a board risk committee demonstrating its oversight accountability and intent.

An important caveat

As in our previous studies, we use board risk committee charters of bank holding companies (BHCs) and nonbank SIFIs, to assess practices in risk governance. Board risk committee charters are guiding documents on board-level risk oversight; they signal the bank’s commitment to risk governance. Risk charters also help stakeholders, such as counterparties, investors, and regulators, understand the role boards play in risk governance.

We acknowledge that charters might not fully reflect all of the actions, policies, and activities that board risk committees at many banks actually follow. Conversely, there may be items in the charters that are not implemented in practice. Nevertheless, clear, direct, and comprehensive articulation of board risk oversight in the charter documentation seems an essential foundation of strong board risk governance.

Study methodology

For our latest analysis, we used 33 criteria to assess the degree to which bank board risk committee charters explicitly outlined or elaborated on various topics. These criteria reflect some key regulatory requirements and leading practices identified by Deloitte subject-matter specialists. They particularly draw heavily on the requirements of the Fed’s “enhanced prudential standards for bank holding companies and foreign banking organizations,”10 and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s “corporate governance principles for banks.”11

We reviewed the following documents, where publicly available:

- Board risk committee charters of bank-affiliated US financial holding companies with assets greater than $50 billion as of March 31, 2017, according to the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC).

- Risk and/or hybrid board risk committee charters, or similar documents, where available in English, of all non-US G-SIBs. G-SIBs were identified using the Financial Stability Board’s November 2016 list.

- Board risk committee charters of US nonbanks that have been designated SIFIs by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC).

In total, board risk committee charters or corresponding documents of 50 banks—28 large US banks and 22 non-US G-SIBs—and 2 US nonbank SIFIs were reviewed and assessed using the questions shown in Appendix A to determine if the charter met each criterion. Since performing this analysis, the FSOC voted to revoke the SIFI status of one large US nonbank. The population is hereafter referred to collectively as “banks” for brevity. The assessments were performed from May through July 2017 using the latest, publicly available documentation, and depended to a certain extent on the professional judgment of the researchers.

Analysis of 2016–2017 charters, and comparison to progress made since late 2014

The Fed’s August 2017 proposal12 laid out Board Effectiveness (BE) guidance, specifying five clear expectations for bank boards to perform effectively. Banks, regulators, and other market participants have likely already begun to adopt them as a frame of reference. Within this context, we thought it would be valuable to assess, to the extent possible, the results of our analysis of banks’ 2016 and 2017 risk committee charters based on these five supervisory expectations.

Overall, we note a significantly higher measure of compliance with regulatory requirements and guidelines by both large US banks and non-US G-SIBs on—for lack of a better word—“vanilla” expectations. These are baseline requirements that relate to the structure and composition of the risk committee, the establishment of the committee’s role in setting risk policies and tolerance, the delineation between risk oversight and management, the committee’s reporting structures, and internal coordination with some other key board committees.

However, we also note potentially large gaps in documenting compliance with some regulatory requirements and guidance, most notably about ensuring the independence of the risk management function. In addition, we only found sporadic or insufficient references to leading practices related to very prominent issues in most banks’ risk environments, such as cyber risk, conduct risk, model risk, and third-party risk.13 Again, as we note throughout, a lack of mention in charters does not translate to actual neglect, yet inadequate attention may indicate immature governance.

Finally, from a geographic perspective, we observe that US banks continue to document their risk committee mandates more thoroughly than their non-US G-SIB counterparts across the vast majority of evaluation criteria, despite some significant improvements in documentation by the latter in several areas. While the focus of our analysis on US regulatory expectations does account for some of these gaps, these differences also outline the potential for these global behemoths to drive the elevation of risk governance standards (see sidebar, “Non-US G-SIBs should grab the opportunity to crystallize risk governance standards”). Please note that the US nonbank SIFIs are included in the US banks’ group due to the general consistency of their results with the latter.

The next five subsections follow the outline of the five supervisory expectations proposed for boards in the Fed’s BE guidance,14 albeit with modifications to reflect how these expectations relate to, and intersect with, our own granular analysis of the risk committees of these boards.

- Setting risk policies, overseeing the risk management and governance framework, and risk strategy and tolerance

- Actively managing information flow, resources, capabilities, and committee discussions

- Holding senior management accountable for overall risk management, and for specific emerging risk issues

- Supporting the independence and stature of the CRO, and risk management and compliance functions

- Maintaining a capable board risk committee composition and structure

“…the firm’s strategy should clearly articulate objectives consistent with the firm’s risk tolerance, and the risk tolerance should clearly specify the aggregate level and types of risks the board is willing to assume to achieve the firm’s strategic objectives.”15 This Fed guidance describes a broad remit of the full board, which works with senior management to set the strategic agenda for the bank. The risk committee has a fundamental role to play in questioning strategic choices and setting risk tolerance at a level that reflects organizational strategy. These responsibilities should complement the committee’s input to the formulation of a risk appetite statement, the risk management framework and its review, approval, and oversight of these key documents.

The Fed’s guidance additionally states: “An effective board considers the capacity of the firm’s risk-management framework when approving the firm’s strategy and risk tolerance . . . An effective board assesses whether the firm’s significant policies, programs, and plans are consistent with the firm’s strategy, risk tolerance, and risk management capacity prior to approving them.”16 Both of these features should be considered core responsibilities of the board risk committee.

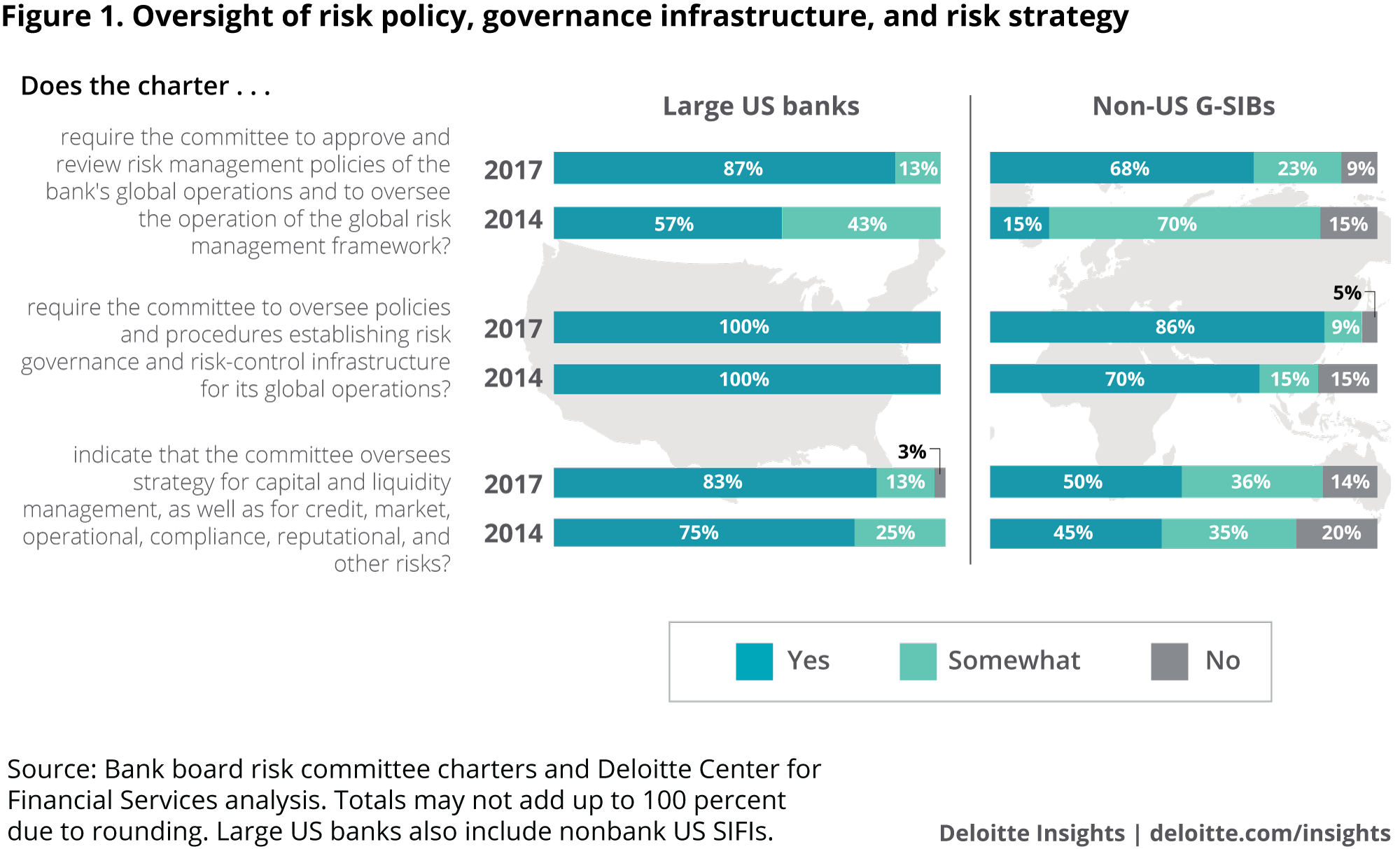

Quite simply, language in risk committee charters that directly relates to the committee’s role in defining the institution’s broad risk appetite, establishing risk management policies, and overseeing the operation of the overall risk management framework seems to have become more prevalent and focused since our last review. Our charter analysis revealed that 87 percent of US banks required the committee to review and approve the bank’s risk management policies and oversee the risk management framework, and 83 percent required the committee to oversee strategy for capital and liquidity management, as well as for a host of individual risk types. Both of these numbers reflect material gains since our last analysis (see figure 1).

Yet, an improvement was expected, since the EPS established these expectations of board risk committees shortly after our 2014 analysis. In fact, the significant progress that non-US G-SIBs have made in mandating these fundamental policy issues, despite not being subject to the same regulatory expectations, is likely more notable. Nonetheless, this measure of documentation seems to only fulfill basic requirements and expectations regarding the role of a bank’s board risk committee.

The Fed proposal noted: “. . . boards of large financial institutions face significant information flow challenges. . . . Absent actively managing its information flow, boards can be overwhelmed by the quantity and complexity of information they receive. Although boards have oversight responsibilities over senior management, they are inherently disadvantaged given their dependence on senior management for the quality and availability of information.”17

Consistent with and building upon the Fed’s view, managing and channeling information flow is also fundamental to boards’ ability to effectively question risk exposure associated with business strategy. Effective information flow structures often go beyond mere metrics related to profits and risk tolerance; that is, many probe deeper than the P&L column. Qualitative reporting of strategy performance can help board members understand and question the potential unintended consequences of business choices. Board risk committee members should also seek to challenge the strength of the risk-control environment, reporting structures and metrics, and training needs that relate to business choices.

In light of the concerns expressed by the Fed, it is encouraging that board risk committee charters generally mandate that committee members have unfettered access to resources, including access to internal executives and information, and the ability to obtain external legal or expert advice. Proactive use of this open access to information, resources, and expertise can be critical for board risk committees to meet regulatory expectations around overseeing and channeling information flow.

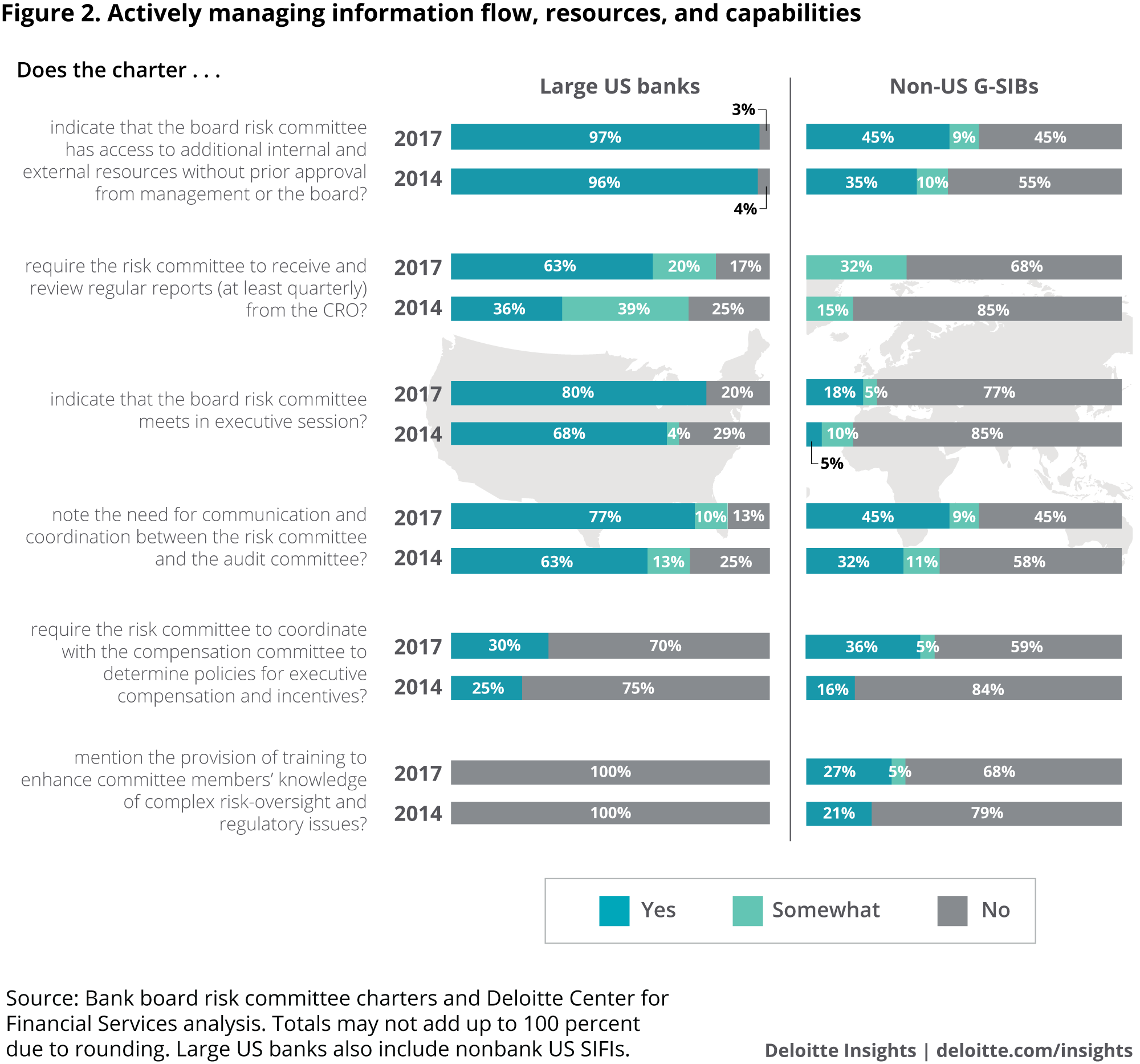

More than eight in ten charters of US banks mentioned that the committee received regular reports from the bank’s chief risk officer (CRO), a requirement stipulated by the EPS. Moreover, a similar percentage of charters noted that the committee had the authority to meet in executive session, or privately with key risk management executives, further promoting healthy information flow and minimizing communication gaps.

Coordinating information flow among different board committees could also play a role in the committee’s ability to meet its mandate. Our research found that documenting coordination between the risk and audit committees of the board has become relatively more common compared to previous years (figure 2). However, coordination between the risk and compensation committees (as also stipulated within the BCBS’ corporate governance principles) is noted in only a few charters. This potential lack of coordination may hinder the risk committee’s ability to effectively oversee management’s implementation of strategy, which may be influenced by the nature and structure of compensation incentives set for management.

Finally, in what was perhaps the most surprising result of our analysis, not one US bank risk committee charter mandated training for committee members. Due to the rapid change in the types, scope, and severity of risks to which most banks are exposed, we consider the lack of a training mandate to be especially fraught. Interestingly, non-US G-SIBs are ahead of the game on this front, with nearly one in three charters mentioning training for committee members.

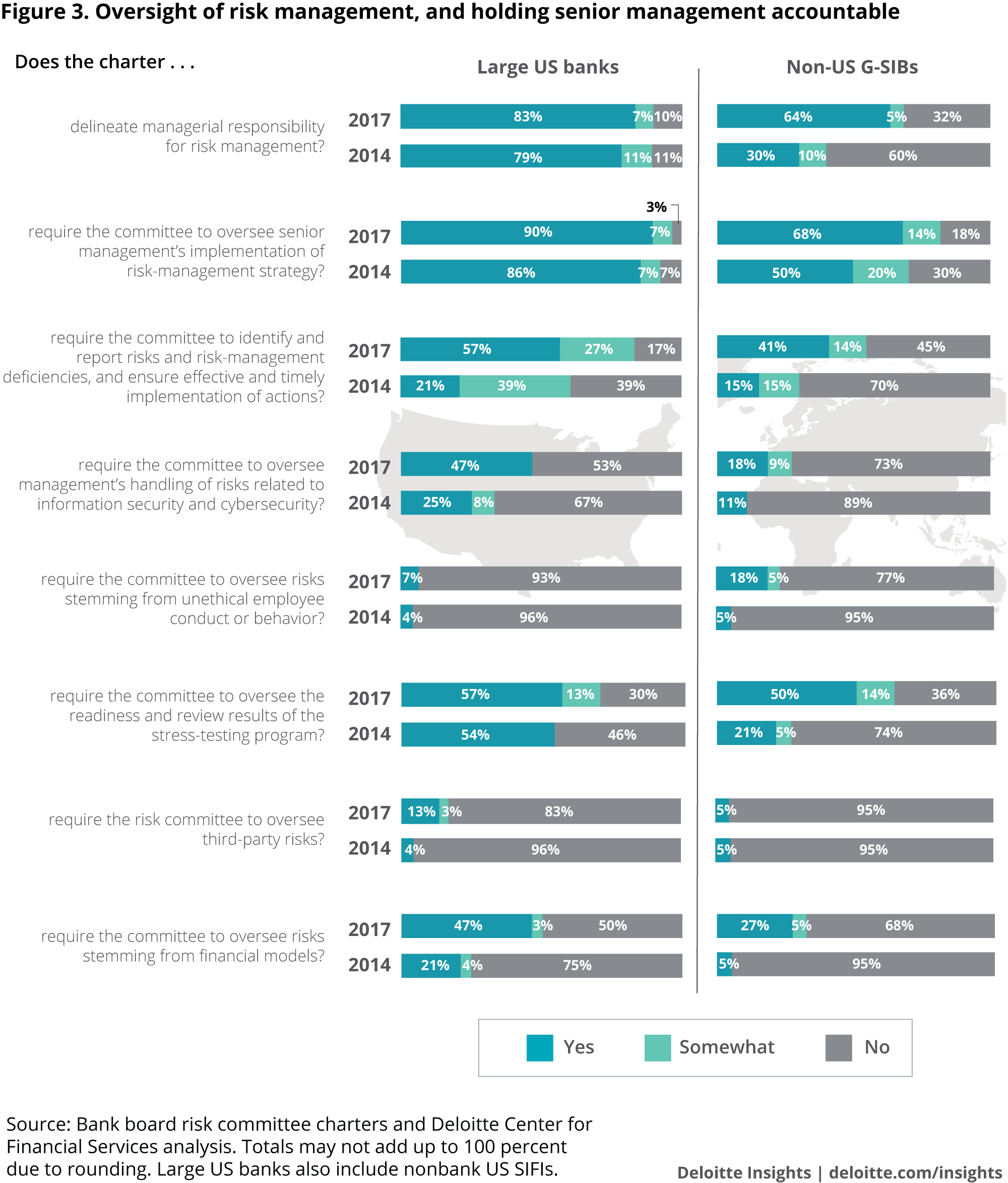

As principal agents for shareholders, a fundamental role of bank boards is to ensure that management is accountable for its actions, which the Fed’s BE guidance also states. Our risk committee charter reviews showed that committees (under the remit of the overall board) appear to be prioritizing this management accountability aspect of oversight. Moreover, in general, it seems the qualitative heft associated with such language in charters has also increased compared to previous years.

Similarly, we found that most risk charters included language that requires committees to oversee management’s execution of risk management strategy. And although the percentage of charters that do so remain at a lower level compared to those of US institutions, non-US G-SIBs have made notable improvements on both these criteria (figure 3).

However, we had expected greater improvement regarding the committee’s role in identifying emerging risks, risk management deficiencies, and in overseeing management’s remedial actions. And the Fed’s BE guidance is also specific about this expectation: “An effective board engages in robust and active inquiry into, among other things, drivers, indicators, and trends related to current and emerging risks; . . . material or persistent deficiencies in risk management and control practices; . . .”18 Explicitly documenting this mandate in charters may drive committees to focus on the information flow, risk control, and governance structures necessary for them to fulfill it.

As noted earlier, our 2017 analysis included new assessment criteria based on recent regulatory guidance as well as emerging leading practices. On the whole, we found most banks’ performance on these new criteria to be quite fragmented. For example, about one-half of US banks’ board risk committee charters mentioned oversight of cyber/information security risk and model risk, both registering notable increases compared to 2014. Committee oversight of stress-testing programs, whether internal or regulator-driven, has also become more notable. On the flip side, mention of third-party risks and conduct risk, both issues that have led to billions in fines for many large banks across the world,19 was surprisingly limited.

Given the scale of these risks, most banks have ramped up programs to confront them. But it is also essential for the board risk committee to have documented oversight responsibility to monitor these programs. In some cases, due to the complexity and interconnectedness of these risks, many risk committees share oversight responsibility for specific risks with other board committees or the full board—another possible instance of the need for tighter coordination among board committees.

As part of the fallout from the financial crisis, many regulators advocated for banks to empower their CROs to serve as the head of an independent risk management function. Various mandates from regulatory agencies across the world noted the need for a strong, independent CRO role, and included requirements or guidance that would enable him or her to act independently of business leadership.

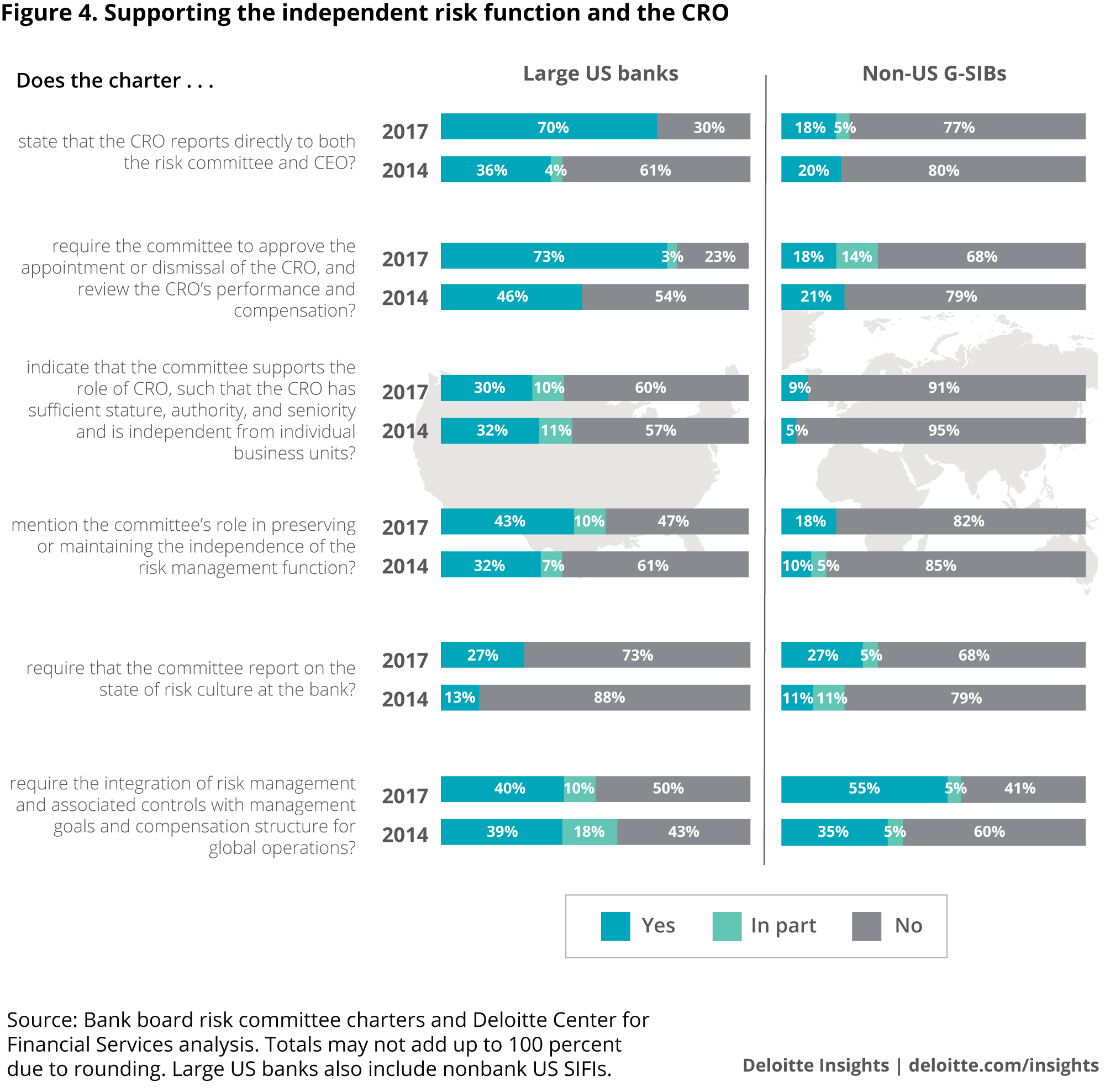

Our latest analysis shows that measures taken to empower the CRO and associated documentation have indeed increased substantively. A comfortable majority of charters now note that CROs report to both the CEO and the board risk committee. Likewise, nearly three-fourths of US bank charters outlined that the committee would approve changes to the CRO’s position and review his or her performance and compensation (figure 4).

However, there appears to still be significant room for improvement regarding the board’s role in elevating the stature and independence of the CRO, which the Fed’s proposal also explicitly endorses: “An effective risk committee supports the stature and independence of the independent risk management function, including compliance, by communicating directly with the CRO on material risk management issues . . .”20 Only a few charters noted the role of the committee in supporting the CRO’s stature and authority within the institution.

Moving past just the CRO's role, when we last conducted our analysis in late 2014, only one-third of risk committee charters stipulated that the committee ensure the independence of the risk management function as a whole, a stated requirement of the Fed’s EPS. Perhaps surprisingly, three years later, only a little more than four in ten US banks’ charters stipulate it. And mention of the committee’s role in integrating controls with management goals and the compensation structure, another EPS mandate, was also low. Hence, it was no surprise that few charters noted BCBS guidance that encouraged the risk committee to report on the state of risk culture at the bank.

On all of these counts, non-US G-SIBs trailed US banks substantially, but it is worth noting that the non-US G-SIBs were also not bound by the US EPS mandates. Nonetheless, given their outsized role in the global financial system, it could be worrisome that few non-US G-SIBs mention supporting the independence of the risk function, let alone the CRO, in their charters.

Nonetheless, for US banks, the Fed’s recent BE guidance should bolster EPS requirements or leading practices for banks’ risk committees to document their support of independent risk management and compliance. In addition, articulating relatively simple practices, such as providing independent risk management with direct and unrestricted access to the risk committee and including representatives of the independent risk management function on senior management-level committees, seem to be powerful signals that the committee is fostering an independent risk function.

The Fed’s BE guidance notes, “An effective board has a composition, governance structure, and established practices that support governing the firm in light of its asset size, complexity, scope of operations, risk profile, and other changes that occur over time. . . . An effective board is composed of directors with a diversity of skills, knowledge, experience, and perspectives. . . . ”21

In 2009, in our first paper in this series, we argued that a risk committee should stand on its own, independent of the audit committee, and have a formal written charter that documents the committee’s authority and risk oversight responsibility.22 Eight years hence, almost every bank in our analysis—in the United States and globally—has a dedicated risk committee, and most also have detailed charters or the equivalent (for example, terms of reference).

Regulatory requirements and guidance played a defining role in this transition. The Fed’s EPS required a separate risk committee with an independent chairman, and every US bank noted this membership requirement in its charter. Likewise, the requirement to have a risk expert on the committee, also imposed by the EPS, has come to be widely noted in charters (see figure 5). However, the risk expertise requirement now creates a wider gulf between the documented compositions of the risk committees of US banks vs. those of non-US G-SIBs, which seem to rarely require the inclusion of a risk expert. And many banks now insist that a majority (or, in some cases, all) of the members of the risk committee be independent.

Meanwhile, some BCBS recommendations, such as ensuring that the chair of the risk committee does not also serve as the chair of the board or the audit or finance committees, still need to be adopted across institutions; if these practices are adopted, they need to be stated in the committee charter. Ensuring that a risk committee chairman is not hindered by the chairmanship of any other committee is sound practice, given the fundamentally independent nature of the risk and compliance functions and, perhaps more importantly, the taxing and time-consuming nature of the job of chairing a risk committee.

As figure 5 shows, global counterparts have also made some progress in promoting independent risk committees. Yet they still continue to meaningfully trail US peers, possibly a sign of local practices as well as US regulators’ more demanding posture in recent years.

Non-US G-SIBs should grab the opportunity to crystallize risk governance standards

According to our analysis, most non-US G-SIBs appear to trail large US banks in crystallizing risk governance standards in a stand-alone charter across most of the dimensions we analyzed. We reiterate that these differences in documentation may not reflect gaps in actual practice, and they can also be partly attributed to US regulations’ heavy influence on our criteria. Non-US G-SIBs also operate in a variety of distinct regulatory regimes and market structures, where expectations about practices, documentation, and disclosure may be different.

Nonetheless, global institutions have an opportunity to raise their risk governance credentials by publicly setting standards similar to US risk committee requirements, especially since many of these institutions have material operations in the United States. A comprehensive, stand-alone board risk committee charter document communicates institutional commitment to risk governance more effectively; it is also a more resourceful touchstone to senior management, board members, and external examiners on the proper mandate of the committee.

French banks, for example, utilize annual “registration documents,” which contain a section for overall board governance, with subsections for committees, including their mandates and a list of the actions taken that year. At first glance, the language in the risk committee section could be considered thin compared to what you would find in stand-alone US board risk committee charters. However, risk governance mandates can be found buried in the risk management references within the sections for business, operating, and service units. Extracting and consolidating these references, and explicitly stating them as board risk committee mandates, would likely better communicate risk management governance intent and practice, and properly delineate it from management. And to clarify, we are not proposing that non-US banks create exact replicas of the US bank risk committee charter. The “terms of reference” document for board risk committees of UK banks, for example, while not a replica, aligns with the spirit of clearly documenting and delineating mandates.

Raising the bar on governance to navigate choppy seas

Analyzing risk committee charters offers us an imperfect but substantive basis to review the current state of risk governance at banks. But pairing our analysis with key priorities that banks face in the risk environment can make it truly valuable. Deloitte recently identified six fundamental risk priorities for financial services firms as they look forward to 2018 and beyond.23 Following are considerations on how bank boards can construct a governance agenda around these six priorities:

Present effective challenge to focus on strategic risk

Unexpected geopolitical shocks, rapid policy shifts (economic and regulatory), and growing activity by nonbank players can influence the risks to bank’s strategic choices, and the risks of those choices. Most firms seem to be concentrating efforts on early identification of external factors to address these strategic risks. Many have already established strategic risk working groups or centers of excellence that are owned by the CRO or the chief strategy officer (CSO) to proactively prepare for strategic threats.24

The Fed, in addressing the governance side of the coin, notes that effective bank boards “set clear, aligned, and consistent direction regarding the firm’s strategy and risk tolerance.”25 Risk committees should fundamentally focus on questioning chosen strategies and their risks, and their institutions’ capability and preparedness to track and manage them. Moreover, the absence of an apparent problem may not be adequate evidence of strategy performance. As we noted earlier, committees should look beyond metrics to evaluate why a strategy is working, probe what a failure would look like, and ask whether things are proverbially “too good to be true.” This overarching focus is important to, and should even influence the type and amount of, enterprise risk appetite and risk management policies.

Oversee the rethinking of the three lines of defense

The delineation of risk control intended by the three lines of defense model—with business units owning and managing their specific risks, risk management providing independent oversight and challenge, and internal audit reviewing the effectiveness of the overall risk-control framework—has been difficult for banks to achieve in practice.26 As management focuses on restructuring and eliminating overlapping responsibilities to create a more efficient governance structure, risk committees should ensure that these efforts strengthen the integrity of the three lines.

Specifically, the committee can help the stature and authority of risk managers through a strong control environment that includes empowering senior risk management executives with the authority to escalate emerging risk issues in a timely fashion to the board. For large global banks operating across multiple regulatory regimes, group boards should also strive to understand the structure and monitor the effectiveness of local and subsidiary boards.27 These local boards often have their own independent directors who are obligated to follow local jurisdiction regulations. Group risk committees should ensure that local boards provide effective challenge to local business heads on risk and strategic issues that pertain to the soundness of country-level entities, whether branches or subsidiaries.

Stay vigilant as management tries to “do more with less”

Executive orders signed earlier this year instructed the US Treasury Department to review financial regulations, including some key mandates of the Dodd-Frank Act.28 Expecting regulatory demands to stabilize, many banks have begun to optimize their internal risk and regulatory compliance footprint. Advances in automation, machine learning, natural language processing, and other cognitive technologies, and big data techniques could help banks meet these objectives.

On a governance level, the risk committee should ensure that optimization and budget reductions do not, in any way, diminish risk management capabilities. Committee members should be dedicated to understanding and challenging the effective capabilities of new technology solutions—even in stress scenarios. Members should also seek to assess information flow in an automated risk reporting and control environment; these IT structures directly affect the bank’s ability to identify and respond to emerging risks.

Strengthen formal conduct and culture programs

In the five-year period to end-2016, the world’s largest banks collectively paid large sums in conduct-related charges, including fines, legal bills, and the cost of compensating mistreated customers.29 Many banks have created conduct risk-and-culture programs, and regulatory focus on the issue of conduct has been more intense. In addition to high-profile US investigations by the Fed, the OCC, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the Senior Managers Regime in the United Kingdom has emphasized individual responsibility to prevent regulatory breaches.30

The first, likely obvious, step is for risk committees to clearly acknowledge oversight of conduct risk and risk culture in the language of their charters. Second, risk committee oversight of culture and conduct risk programs should look particularly at decision-making processes around product and service design, with a focus on senior management accountability. Risk committees can also set the right governance tone by demanding higher-than-required standards of compliance from management that includes enforcing a zero-tolerance policy on ethics breaches at all levels, and ensuring that conduct assessments are included in performance evaluation and compensation-setting processes.

Focus on the interconnectedness of risk

Many risks not only span the purview of specific business units, but of specialized committees outside and within the board of directors. Accordingly, board risk committees should work with other committees at the board level (for example, technology, audit, remuneration, and operations) and with management risk committees embedded in businesses to identify and understand risks holistically. While the EPS required designated risk experts to be part of the board risk committee, boards should also seek members with new types of expertise. For example, more institutions appear to be actively recruiting directors with technology expertise.31 Another way to approach interconnectedness is to prioritize training, which should include updating members’ knowledge of key risk and regulatory issues as well as helping them determine the right measures for oversight, enabling them to be effective stewards in a more complex operating environment.

Oversee the strategic management of capital and liquidity

Of all the risk management capabilities that most banks have built since the financial crisis, capital and liquidity stress-testing at an enterprise-wide level may have matured the most. As regulatory expectations around capital and liquidity standards have evolved, most banks have begun to use measurement tools and analytics not only for compliance, but also as guideposts for strategy. As we noted earlier, risk committee and board attention to stress-testing programs seems to have likewise increased substantially.

However, if business activity and loan growth eventually accelerates, banks could face tough choices in allocating capital and liquidity. Board risk committees would have to walk this tightrope while making sure that balance sheets continue to possess adequate capital and liquidity buffers. Extending robust enterprise-level analytics to subsidiary, function, and regional levels can provide board members insight through which they can more actively exercise their oversight of risk tolerance.

Orienting the compass to meet renewed expectations

As we conclude our study, let’s take a moment to reflect on the progress that banks have achieved in the area of risk oversight and governance. Even as late as 2011, having a dedicated risk committee on the board—now ubiquitous—was viewed as a leading practice. The codification of regulatory requirements, along with other leading practices, has contributed to more vigilant governance structures, potentially more resilient institutions, and hopefully a more stable banking system.32

However, as Fed Governor Daniel Tarullo had remarked as early as 2014, it was becoming apparent that the increasing operational burdens placed on bank boards were drawing director attention away from strategy and risk-related oversight.33 From this perspective, the recalibration and focus that may result from the Fed’s August BE proposal should help improve the quality of risk governance. And it would likely be a mistake to view the Fed’s new guidance as an easing of expectations. As Fed Governor Jerome Powell remarked at the Large Bank Directors conference in Chicago earlier this year, “We do not intend that these reforms will lower the bar for boards or lighten the loads of directors. The new approach distinguishes the board from senior management so that we can spotlight our expectations of effective boards. The intent is to enable directors to spend less board time on routine matters and more on core board responsibilities . . .”34

To that end, board members should prepare for these changing expectations with the operating principle of presenting effective challenge to management across the breadth of strategic issues, something we have reiterated throughout this paper. To meet and exceed expectations, board members should focus on creating robust information flow structures (especially around emerging risks), actively empowering the independent risk management function, and keeping pace with growing complexity in the risk environment.

Quite simply, now is not the time to stop evolving.

Appendix

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.