Managed services has been saved

Managed services A catalyst for transformation in banking

22 March 2017

As part of their ongoing efforts to innovate and grow, some banks are leveraging managed services to help bridge gaps in internal capabilities and adopt a more holistic, value-based approach to outsourcing. Learn what’s behind this trend, when it works well, and why.

Introduction

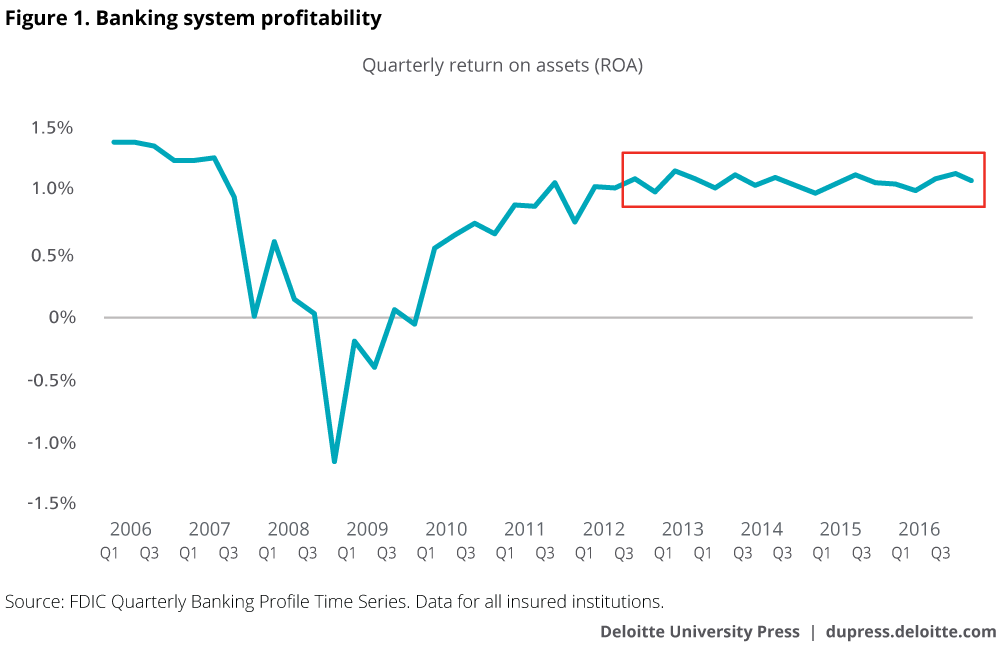

It may be tempting to imagine that the structural transformation banks have undertaken for nearly a decade is giving way to a period of stability. But the future will possibly show otherwise. While there has been more stability in recent years, the industry’s core operating profitability has been far from impressive (see figure 1) and needs a boost through innovative cost management as well as alternate revenue streams.1 Spurred by new technologies and an evolving competitive landscape, banks should continue their ongoing transformation.

This transformation may be especially needed in risk management and regulatory compliance. According to Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited’s (DTTL) most recent global risk management survey (10th edition), risk managers from financial services firms believed “cyber risk” and “regulatory or compliance risk” would grow the most in importance over the next two years.2 As regulatory paradigms evolve, many firms will likely continue to prioritize sharpening institutional expertise in risk management, compliance, internal controls, technology integrity, and data management.

Managing these business-critical processes requires vast resources, both internal and external. Take regulatory compliance, for instance. It now costs the banking industry nearly $270 billion annually, or 10 percent of operating cost, to meet the demands of regulatory compliance.3 Much of this spend is because many of the biggest global banks have doubled the size of compliance and regulatory teams.4 This expansion in internal compliance resources occurred even as institutions increased reliance on third-party firms in myriad areas: Banks around the world have spent nearly $200 billion on consulting services in the years following the financial crisis.5

Amid this period of heavy investment in risk management and regulatory compliance, some firms are choosing to bridge gaps in internal capabilities and adopt a more holistic and value-based approach to outsourcing relationships by using managed services. Managed services are strategic, experience-driven, outcome-based relationships with high levels of operational integration and scalability that leverage the specialized skills, processes, and technology of an external service provider.

Exploring managed services for your organization

Who should care about managed services?

Risk and operations decision makers across banking and capital markets firms should closely observe the evolution and integration of managed services within the industry’s operating models. Managed services are strategic, long-term relationships by definition, demanding the attention of senior leadership spanning the banking organization. And with growing complexity and operational integration in relationships between banks and their providers, monitoring the adoption of managed services could also be an important consideration for bank regulators.

Some key questions to evaluate

Organizations should seek to understand several critical issues about the application of managed services in the context of their overall strategy, culture, and structure. Through this paper, we attempt to answer the following questions to help banks make these assessments:

- How are managed services different from traditional outsourcing?

- How can organizations create a framework to determine which activities can benefit from managed services? In particular, how could managed services benefit the risk, compliance, and governance functions within banks?

- What are the qualities to look for in a managed services provider? How can managed services help balance different stakeholders’ demands?

- What are the key considerations in implementing managed services? What risks should be evaluated before entering a managed services relationship, and how can these be managed?

Traditional outsourcing in the banking industry

To view managed services in the right context, it’s often helpful to understand the evolution and growth of outsourcing in financial services companies. Historically, banks have used a variety of outsourcing models to maximize resource efficiency. These models have evolved with changing times. A good example of this progression is business process outsourcing (BPO), which has existed for at least several decades. In 1992, American Express (Amex) spun off its transaction processing unit, where it already had developed scale and experience, and partnered with a third-party card processing unit. Amex anticipated the commoditization of the transaction processing business, so it placed a strategic bet to focus on the growth of the card issuing business.6

Cost mutualization, where firms, or divisions within a multi-business organization, collaborate to create a utility-like entity, has been another common outsourcing strategy. One example is the Know-Your-Customer (KYC) Registry launched in 2014 by SWIFT, the global provider of financial messaging services.7 The registry is a centralized utility that decreases the burden of banks’ KYC compliance requirements through cost mutualization and enables industrywide standards in data formats and structure. From small beginnings, this effort now includes more than 3,000 financial institutions in over 200 countries.8

Outsourcing to third parties is only expected to increase in the future, especially in areas of the enterprise that do not significantly enhance competitive differentiation.9 Since the birth of the modern corporation, the trade-offs of using external resources vs. internal capabilities have been a perennial theme in management strategy. The in-house approach may provide greater control, but impacts time-to-market and diverts management attention away from innovation, both key determinants of success. Conversely, the reliance on third parties, although beneficial in cost reduction and other ways, carries risks that may not be apparent up-front, including reputational, contractual, and information security risks.10

Evolving from traditional outsourcing to managed services

DTTL’s 2016 Global outsourcing survey of executives from firms representing 26 sectors found that “respondents [across industries] increasingly see outsourcing as a vital way to drive innovation into the enterprise. . . . It is becoming a means of potentially attaining and maintaining a competitive advantage—and not just a way to cut costs.” Academic research supports this viewpoint, showing how strategic outsourcing drives value to firms.11

As firms’ expectations of providers increase, the scope of outsourcing is widening. Managed services could be the next stage in this evolution. Banks can proactively limit enterprise risk and strengthen compliance by using well-designed managed services to address deficiencies in internal talent, improve process quality, and adopt technologies to keep up with market trends. Ultimately, such relationships often refocus managers on growth, innovation, and bolstering the competitiveness of their core business.

To frame our perspectives on this topic, we relied not only on existing academic literature and the experiences of Deloitte professionals, but also on discussions with business executives. Twelve C-suite executives from a range of industries, including financial services, shared their views on the topic of managed services, with a particular focus on compliance or risk management functions.

How are managed services different from traditional outsourcing?

Traditional outsourcing applications span a wide spectrum. IT outsourcing and BPO models include staff augmentation contracts, infrastructure-as-a-service, and subscription-based software-as-a-service models. Cost mutualization, also a form of outsourcing, is common in the industry; examples include custodial entities in the financial markets, or internal shared services organizations in large global banks with different business lines.

Cost management has historically been the primary motive for outsourcing.12 This still holds true: DTTL’s 2016 Global outsourcing survey showed that cost remains the top driver of outsourcing decisions today.13 But firms are now also looking for specialized knowledge at scale to solve complex problems. Many are seeking relationships with long time horizons instead of short-term, transactional exchanges. A specific characteristic of such relationships—the sharing of risk in outcomes—is increasingly attractive to many organizations.

Think about cybersecurity, a function typically managed in-house. In 2016, financial services industry firms incurred an average cybercrime cost of $16.5 million, the highest across all industries.14 This functional area not only poses a high degree of enterprise risk, but is also growing in complexity. In a letter about its customer security program sent to its customers late last year, SWIFT noted that there “are likely to be multiple groups of cyberattackers attempting to compromise customer environments.” SWIFT also noted that “there has been an evolution in the modus operandi, signifying that attackers are further adapting their methods.”15 The problem is often compounded by the challenge of acquiring and retaining qualified talent that demonstrates a confluence of “technical, business know-how, and strategic thinking capabilities to implement cyber risk initiatives quickly and effectively,” as pointed out in the Deloitte Center for Financial Services’ (DCFS) study on cyber risk management in financial services last year.16

Clearly, banks aspire and need to achieve stronger cyber risk management capabilities. Money doesn’t seem to be an object—the DCFS study found that cybersecurity budgets have risen dramatically.17 But keeping up with the growing number and complexity of threats, managing legacy infrastructure, framing a proactive cyber strategy, and dealing with talent challenges are serious hurdles. Could firms appropriately access knowledge and experience that exists outside their organizations to limit risk while overcoming these challenges?

The use of traditional, cost-focused BPO in such a critical activity, one might argue, is suboptimal. At first glance, there would be the lack of available, high-quality expertise at adequate scale. Next, the nature of the cybersecurity function demands extremely close integration with an external provider, something that can be difficult to achieve in contract-based outsourcing, which tends to become transactional. Outsourcing service agreements now generally include curative provisions and clawbacks for process failures,18 yet the nature and degree of failures are different compared to a cyber incident, for instance. Instead of reduced systems availability in IT outsourcing, customers’ personally identifiable information and company trade secrets may be compromised due to weak cybersecurity safeguards. The costs of such a failure can be hard to measure and may pose existential risk to the institution.

In this case, a well-structured managed services relationship can be a strategic solution. Continuing with the cybersecurity example, a managed services provider brings in experience spanning multiple organizations (for instance, around information sharing, risk measurement, and reporting consistency) to build and manage a proactive cyber risk defense-and-response mechanism, replacing reactive approaches. While this provider would be charged with notifying the firm about a potential breach of security, it also brings to the table a wider tool-set, including threat intelligence and analytics, threat response, breach remediation, identity management, cyber strategy design and governance, third-party cyber risk exposure limitation, and vulnerability assessments. Often critical to this capability is a talent pool that possesses the relevant functional skills and can adapt to a rapidly growing knowledge base. Providers in such long-term and outcome-based relationships also typically have “skin-in-the-game” to invest their full resources, capabilities, and institutional expertise to achieve the desired outcomes for their clients.

For banking and capital markets, governance, risk, regulation, and compliance are some key challenges where managed services are immediately relevant. We will now narrow our focus to managed services in banks’ risk and compliance activities to offer more specifics about how managed services relationships generally work and when it may be appropriate to use them.

Which operations in banking and capital markets could benefit from managed services?

Significant shifts in banks’ operating environments and business models have created an environment ripe for the application of managed services. However, the scope of these experience-based relationships should be tightly defined. To that end, we present a simple framework composed of four questions, to help banking institutions assess operating model choices—managed services, traditional outsourcing, or in-house execution—for three different banking activities or functions.

Our first example considers the design and validation of internal controls. When banks fail to identify weaknesses or process gaps in internal controls, deficiencies can grow to be systemic and cause severe financial and reputational damage to the enterprise, hurting long-term sustainability. But while process excellence in this critical task tends to lead to a more vigilant and agile organization, it creates little differentiation for the bank in the marketplace. Customer perceptions of a bank’s products and services are unlikely to be influenced by the quality and integrity of its internal controls.

For a long time, banking organizations have demanded specialized talent for internal controls, but in recent years, the industry has experienced a paucity of highly technical experts. The greater the number and complexity of internal controls and the procedures to validate them, the more likely that lapses in oversight may occur. Moreover, the functional knowledge base for many areas is expanding and deepening quickly. This high velocity of change can make it difficult to ensure that in-house staff in specialized processes possess cutting-edge domain knowledge and skills. For instance, growing concerns around data security or the integrity of new technology might demand additional controls that internal managers may not be well-equipped to develop and institute.

The intersection of these four attributes in critical activities, ranging from the example of internal controls discussed above to ones such as tax compliance or cyber defense, present a specific mix of challenges that managed services may be well-suited to address, as we illustrate in figure 2.

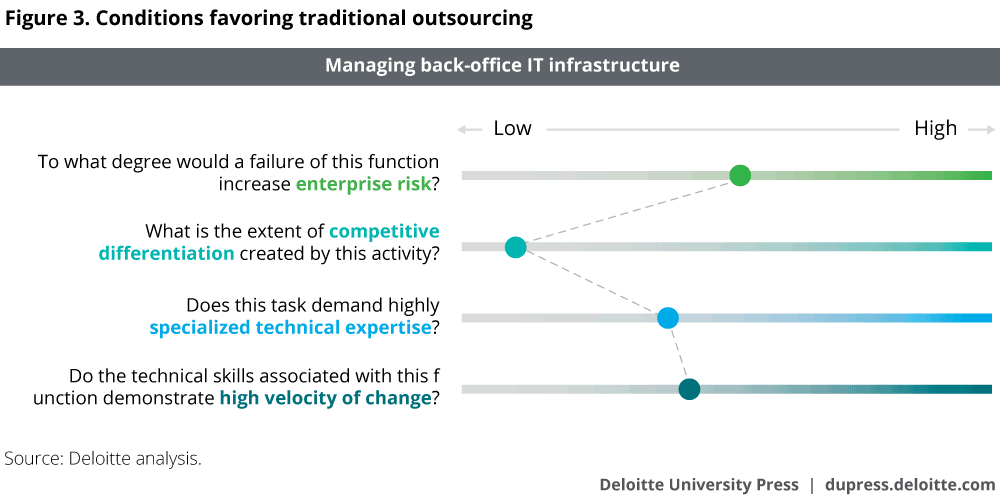

In contrast, consider the case of managing back-office IT infrastructure (figure 3), a process that firms across industries have outsourced in the past. These systems are important to the everyday operations of the bank yet pose varying levels of enterprise risk if deficient: While a failure of the core deposit system may be crippling, lags in some ATMs or the digital banking platform would likely be less damaging. These activities also demand some measure of specialized technical expertise, but back-office IT infrastructure by itself is rarely a competitive differentiator. Furthermore, even if the technology, especially cloud-based infrastructure, may be changing rapidly, the talent gap may not be as pressing an issue. The cost reductions that firms have achieved from the outsourcing of such activities have generally been a sound value proposition.

Our third case pertains to credit underwriting and monitoring (figure 4), which—in many respects—is the beating heart of any bank. While risk to the enterprise as well as competitive differentiation (especially on the commercial loan book) are both very elevated, talent for this function is relatively simple to hire, and the functional knowledge base in this area is well-trodden and has evolved only incrementally. The nature of this activity—a differentiating task that can be effectively performed and continuously upgraded within the bank—suggests that it should likely remain in-house.

The four criteria we consider—enterprise risk, competitive differentiation, specialized technical expertise, and velocity of change—address the urgency of resource acquisition due to the level of risk involved, the proprietary nature of the task, the ability to hire talent at scale, and the likelihood that talent would remain equipped with and acting upon the latest knowledge in the field. A strategic managed services relationship is often most applicable when resource needs are urgent, specialized, and evolving quickly, but where competitive differentiation from the task is low or moderate. In these scenarios, the costs and challenges of building a cutting-edge function in-house may not pay off by enabling adequate differentiation in the marketplace.

Lessons learned: Why one life sciences firm turned to managed services

The banking and capital markets industries share some important common characteristics with the life sciences industry. Like banks, life sciences firms are heavily regulated worldwide. Companies are required to draw on specialized compliance and technological expertise to maintain reliable internal processes. Similar to banks, life sciences companies have also witnessed significant change in the regulatory environment.

An operational risk management issue shared by both industries is technology integrity; that is, verifying that all IT systems and software applications fulfill their intended purpose within stated performance parameters. Rapid development cycles, increasing volumes of data, phasing in of new technologies and platforms, and limited staff with the requisite skills pose operational and budgetary concerns. Moreover, process failures or noncompliance pose significant business risks, including disruption of customer-facing and internal operations, not to mention potential fines, penalties, and reputational damage—outcomes that banks also have to protect themselves against.

Several years ago, a global Fortune 100 life sciences firm outsourced its systems validation processes using traditional staff augmentation to achieve cost efficiencies. After a painful transformation, end-to-end process needs still remained unsatisfied. Gradual degradation in service levels followed; the provider focused on meeting the bare-minimum process requirements and efficiency parameters stipulated in the contract. The firm decided to replace the vendor, but found the quality of standard outsourcing offerings in the marketplace insufficient. With this operating model, vendors had little incentive to focus on process success as it related to business success.

More critically, this compliance unit lacked the technical expertise, adaptability, and decision-making maturity to keep pace with rapid changes in the business and regulatory environment. Competitors, especially nimble start-ups, could leverage new technologies faster to create a competitive advantage. The compliance team’s inability to facilitate adoption was therefore directly hurting the business.

In response, the company chose to enter a managed services relationship characterized by two key attributes: First, the managed services provider brought high-quality talent with not just technology and regulatory expertise, but also the maturity to make risk-sensitive decisions about adopting new technologies, such as robotics and advanced cloud applications. Second, the relationship was structured on an output-based pricing model, instead of the typical hourly billing approach. The company benefited from much more expense predictability, and for the managed services provider, this pricing structure created incentives to strengthen testing, validation, and reporting processes. Compared to the curative clauses generally used in traditional outsourcing, here the provider’s remuneration was tied to delivering results up-front.

The provider also insisted on consistency in enabling technology to reduce process gaps, a simpler organizational structure for better communication, and established procedures for escalation within the provider’s team and with functional executives at the firm. This holistic alignment of people, process, and technology created value additions to the systems integrity process, making it more responsive to business needs. It also improved the integration of the function with the wider enterprise. Not only did initial performance metrics improve to the satisfaction of the firm, but the managed services provider was also able to set the stage for a long-term relationship.

This application of managed services tightly aligns with the criteria we defined in the framework above—the risk inherent in the task was high, the nature of talent needed was specialized, the knowledge base in the function was evolving rapidly, but competitive differentiation from the task of systems integrity itself was relatively low. The confluence of these criteria made the use of managed services with aligned incentives for a provider an appropriate management choice.

What to look for in a managed services provider

Managed services involve a significant transfer of operational control in critical tasks from firms to the service provider. Yet traditionally, the operational risks inherent in outsourcing have made many firms reluctant to share control of such activities. To alleviate internal stakeholders’ concerns, certain qualitative and contractual factors should be considered in this new operating paradigm. Discussions with executives generated some key criteria that are often used to select a managed services provider:

- A track record of domain expertise, and an understanding of the compliance, risk, and auditing functions are often considered critical. A managed services provider should also demonstrate maturity in process design and execution that limits risk, enhances auditability, and actively detects new vulnerabilities.

- High-quality staff and a process management team with access to intellectual property and technology that bridges the internal expertise gap are generally obvious requirements. However, banks should also consider insisting on a measure of continuity, with clear expectations around staff turnover rates in the provider’s team, and contingency plans in case key personnel leave.

- An up-front assessment of fit—across tangibles such as technology systems and work processes, and intangibles such as culture—between the bank and the service provider can prevent future surprises.

- The provider’s reputation with other industry participants and credibility with regulators, supervisors, and vendors (such as marquee software firms) likely speak to its ability to be a responsible long-term provider. The presence of its own thought leadership in banking and relevant risk or governance functions may also indicate a stronger ability to anticipate emerging business issues.

- A global footprint combined with the ability to understand the operational nuances of cross-border businesses could be an important consideration for large global banks and capital markets firms, which often have to deal with conflicting regulatory mandates and fragmented policy environments.

- Finally, institutional strength, measured by financial soundness, size, and the general ability to compete for high-quality talent, are factors that may directly affect the provider’s ability to consistently deliver high-quality services over a long period of time.

Of course, cost inevitably plays a role in the decision, but discussions with executives suggested that the characteristics of successful collaboration, outlined above, often took precedence. This is likely due to the fact that managed services are applied to critical functions of a bank’s operations. In addition, these characteristics likely merit ongoing monitoring throughout the life of the relationship, as changes may impair the provider team’s performance and expose the bank to risk.

Managing the interplay of different stakeholder demands

Our discussions with senior executives yielded a curious mosaic of the internal organizational dynamics involved in implementing a process externalization model. The goals and pain points of different stakeholders obviously vary based on the type of activity, and are particularly intense for critical processes. A well-considered application of managed services can bridge many of these differences.

For instance, executive interactions suggested that many boards of directors are particularly concerned with prominent headline risks to their enterprise, cybersecurity being a fundamental area of focus these days. Therefore, the board typically prioritizes reputation and track record when choosing a provider, a top consideration in adopting a managed services strategy.

Meanwhile, though chief executive officers are concerned with prominent headline risks, they also generally want process challenges to be resolved efficiently so that they can focus on more strategic business decisions. This prioritization, again, reflects the limited differentiation inherent in the activities in which managed services may be most applicable.

From an execution standpoint, in many instances chief financial officers own the relationship with managed services providers, and are tasked with making value judgments from a short-term financial and long-term sustainability perspective. Managed services that operate based on clear, outcome-based pricing models typically offer a solid foundation on which these relationships can be structured.

For chief risk and operating officers, demonstrable technical expertise is generally the prime consideration. Additionally, these executives often have to deal with three major issues: discomfort at giving up operational control, the need to take ownership for an external service provider’s potential failure, and managing any talent disruptions that can emerge from engaging in such a relationship. The expertise benefits inherent in a managed services model can overcome some of these operational challenges, as the process at hand necessarily requires domain knowledge that may be lacking within the enterprise.

Given the divergent and often conflicting priorities of these different internal stakeholders, the application of a managed services model is likely to be more effective when viewed as a strategic choice within the bank. The concerns of different stakeholders should be reflected in specific and measurable goals that a provider should be able to achieve. Using such a mechanism to form organizational consensus can underpin a results-oriented and sustainable professional services relationship.

What are the key considerations in implementing managed services?

The nature of functions and degree of risks shared with a managed services provider should result in a tightly integrated relationship. But regulators, such as from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), are carefully watching the rise in the number and complexity of banks’ third-party relationships.19 Consider, for instance, scenarios in which a third party becomes an “integral component of the bank’s operations” or helps banks address “deficiencies in bank operations or compliance with laws and regulations.”20 With the OCC’s heightened focus on banks’ risk management procedures and surveillance of third parties,21 organizations should be mindful of several critical execution issues.

Managing the life cycle of risk: Trusting an experienced provider to handle a critical process introduces new principal-agency risks to the bank, which typically require the creation of financial and legal structures to tackle them. Foremost, to ensure that the provider has adequate “skin-in-the-game,” indemnification and clawback agreements triggered by process failure could be written into contracts. Obviously, the nature of these agreements would vary based on the type of work as well as the extent of operational transfer involved. In some cases, it may be difficult to estimate the extent of liability from a potential lapse. Banks may therefore want to insist that the provider obtain liability insurance to guard against outsized financial losses.22 Additionally, the distribution of decision-making accountability between internal executives and the provider’s team should be clearly delineated and dispute resolution mechanisms, such as arbitration and judicial recourse, should also be clearly stated.

Piloting, transitioning control, and establishing oversight: The steps of transition and workflow handover to the provider team typically depend upon the type of process involved. Some narrow activities may be better suited to using a parallel run, with the internal team ramping down once the effectiveness of the provider’s process has been verified. This is akin to software applications running in a test environment. Banks are familiar with this process, too—internal risk-based capital models have been implemented through regulator-supervised parallel runs in institutions around the world. But for complex and more extensive workflows, implementing parallel runs would likely be costly. In these cases, workflow may be transitioned better using a staggered schedule, with the provider and internal team working together on select stages. When initiating an activity that is completely new, such as a new risk management or regulatory compliance process, banks may also benefit from piloting select stages of the process, making course corrections along the way. From a governance perspective, having a transition or implementation period is also an ideal time to establish reporting, oversight, and remediation controls for the new process.

Mitigating employee, investor, and regulator concerns: As discussed earlier, some key stakeholders may experience discomfort when faced with the loss of operational control resulting from process externalization. Focusing on the strategic rationale to implement managed services—an ultimately stronger process—may be a way to address these concerns. The reputation, expertise, and performance track record of the provider could play a big role in acquiring the necessary buy-in from external parties such as regulators, while displaced talent could be internally re-skilled to focus on core business activities.

Forging a path forward with managed services

Whirlwind change over the last eight years has left many banks juggling a myriad of growth, operational, regulatory, and technological priorities. Although most have adopted traditional outsourcing models to delegate business functions to manage costs, retaining control of both high-risk and high value activities in-house has been the unsaid norm, and perhaps rightfully so. Until now.

Managed services take the notion of outsourcing to the next frontier. These outcome-focused strategic relationships take control of business-critical functions that are integral to protecting a firm’s overall value. Given that this model propagates a big change in firms’ modus operandi, three critical pillars—specialized skills, reliability of service outcomes, and trust in the managed services provider—form the foundation of successful managed services relationships.

While straightforward enough, the rewards of the managed services operating model are potentially vast. Banks and capital market firms get scalable process expertise and, simultaneously, gain the confidence to reallocate their most critical resources to focus on top strategic priorities: core business growth, differentiation, value creation, and profitability.