Redesigning customer privacy programs to enable value exchange How financial services firms can make privacy a competitive differentiator

15 minute read

09 November 2020

Privacy is a two-sided coin for financial services firms. On one side: formidable challenges. The other: untapped opportunities. Learn how firms can flip the coin to build value and engender more consumer trust.

Key messages

- Our survey findings reveal that privacy concerns remain top of mind for most consumers, and in fact, seem to have only grown since the pandemic.

- Respondents are often unwilling to share more personal information, creating a high bar for financial services firms that will likely keep rising as new data collection tools and technologies proliferate.

- Despite these concerns, many respondents seemed willing to provide financial services firms more personal data in exchange for added value and benefits—but only if it is clear why the information is needed, how it will be used, and what’s in it for them.

- Privacy policies are often a missed opportunity for financial institutions, which should go beyond issuing the usual, compliance-centric statements to create a more powerful tool that establishes an ongoing, mutually beneficial dialogue with consumers.

- To make privacy management a competitive differentiator, financial services firms should establish a strategic, collaborative effort across multiple business functions, including marketing, risk, and, of course, compliance.

The bar for privacy keeps rising

Right now, privacy programs in the financial services industry seem to be a purely defensive exercise that focus almost exclusively on data protection and regulatory compliance. Many firms’ privacy policies are not forward-looking and fail to account for new forms of data and tools to collect and analyze information.1

Learn more

Explore the Financial services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Most importantly, based on our analysis, it seems there is rarely any give-and-take with consumers to explain what kinds of data firms need to effectively serve customers. Firms rarely explain to consumers why sharing such information might be mutually beneficial. The lack of these kinds of communications could be a self-defeating strategy in the long run.

What if, instead, privacy policies were expanded to become something bigger and better—in fact, a competitive differentiator?

This is not a small task. Clearly, addressing privacy and its many facets could require a radically new paradigm. As a follow-up to Deloitte’s 2019 report, Reimagining consumer privacy for the digital age,2 and to glean additional insights, we surveyed more than 2,000 consumers in the United States to estimate trade-offs consumers are willing to make in exchange for additional value. (For details, see the Methodology section in the Appendix.)

Our survey findings reveal that privacy concerns remain top of mind for most consumers, who are often unwilling to share their data. As a result, banks, insurers, and investment management firms have a high bar to clear to convince customers to share more information than what is required of them. This bar will likely only keep rising as new tools and technologies in collecting data continue to proliferate and become popular.

However, our survey revealed that under the right conditions, some consumers would be willing to share data with their financial providers—if they receive some additional benefit in return. To enable this value exchange, financial institutions should design a clearer, more robust interactive privacy management strategy that involves all business functions, not just compliance.

Concerns about privacy are complex and multidimensional

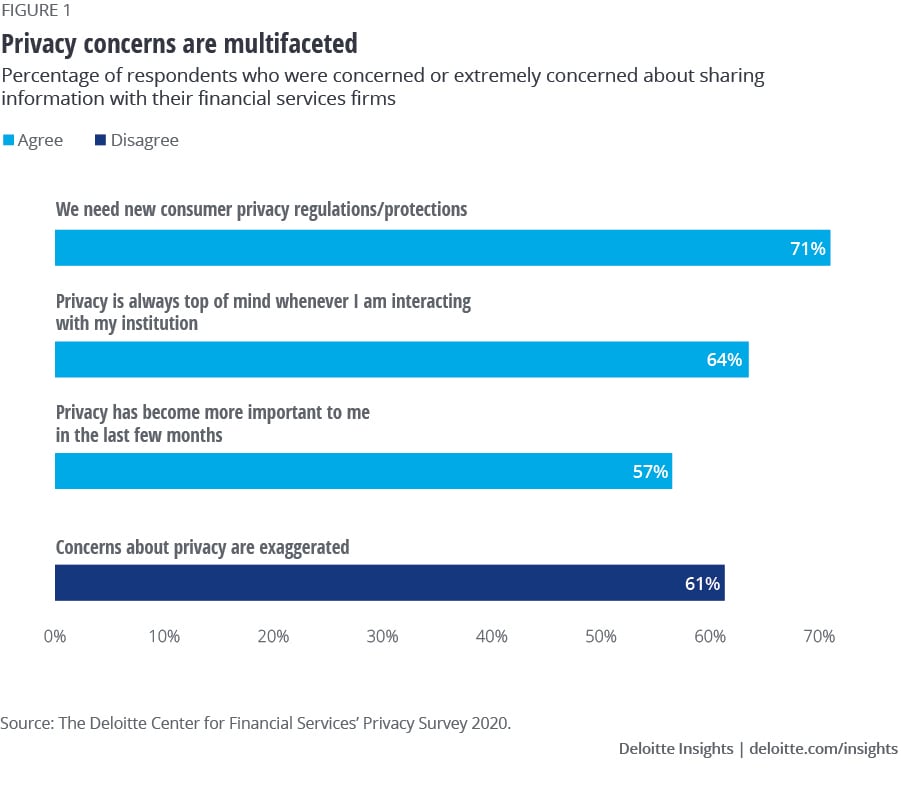

Our survey confirmed that most consumers are worried about privacy: 64% of respondents said that privacy is always top of mind whenever they interact with their financial services institution. The pandemic appears to have only heightened these concerns: 57% of respondents agreed that privacy has become even more important in the last few months. Most consumers (61%) also firmly disagreed with the notion that concerns about privacy today are exaggerated (figure 1).

Sharing financial information topped the list of privacy concerns in our survey. Approximately 56% of respondents said they were most concerned about sharing their financial information, followed by 27% who rated sharing health information as most concerning. Concerns about sharing other types of information, such as online browsing history, social media usage, and shopping habits, for example, appeared to be significantly lower.

But overall, most consumers surveyed were either uncomfortable or unwilling to share any piece of data with financial services providers. Respondents clearly wanted to have control over the data collected by their financial institutions: 83% wanted the opportunity to opt out of sharing certain types of information, and the same percentage said they were uncomfortable with their provider sharing their information with third parties, especially without their knowledge or permission.

Respondents also expressed great concern about the accuracy of data collected about them by their financial institutions from third-party sources. Seventy-nine percent felt strongly about wanting an opportunity to verify information used by their financial institutions.

Furthermore, most survey respondents wanted more clarity about ways to protect their privacy when dealing with financial institutions. About 80% wanted their providers to be clearer about what types of data they were collecting and how that information would be used. Such sentiments were elaborated upon in responses to open-ended questions. One respondent summed up the consensus: “Privacy while dealing with financial institutions to me means clear communication regarding my rights and how my data will be used, stored, and shared, and allowing me some choice in this matter. I should be updated whenever a policy changes that impacts my privacy in regard to said financial institution.”

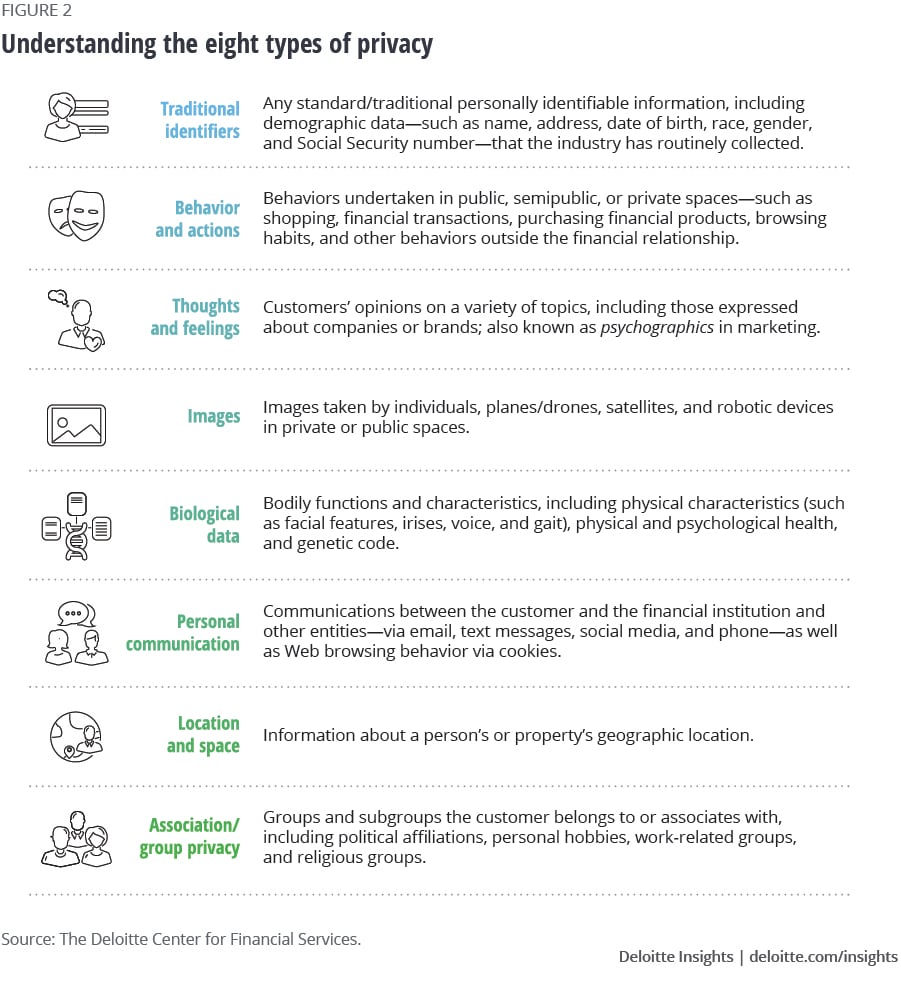

Achieving clarity in communications and giving consumers more control over their data, however, will likely be challenging because consumers are concerned about various types of privacy and data mining technologies and tools. In our first report, we identified eight types of privacy (figure 2) that highlight its multidimensionality, as well as various technologies and tools that could encroach on each type.

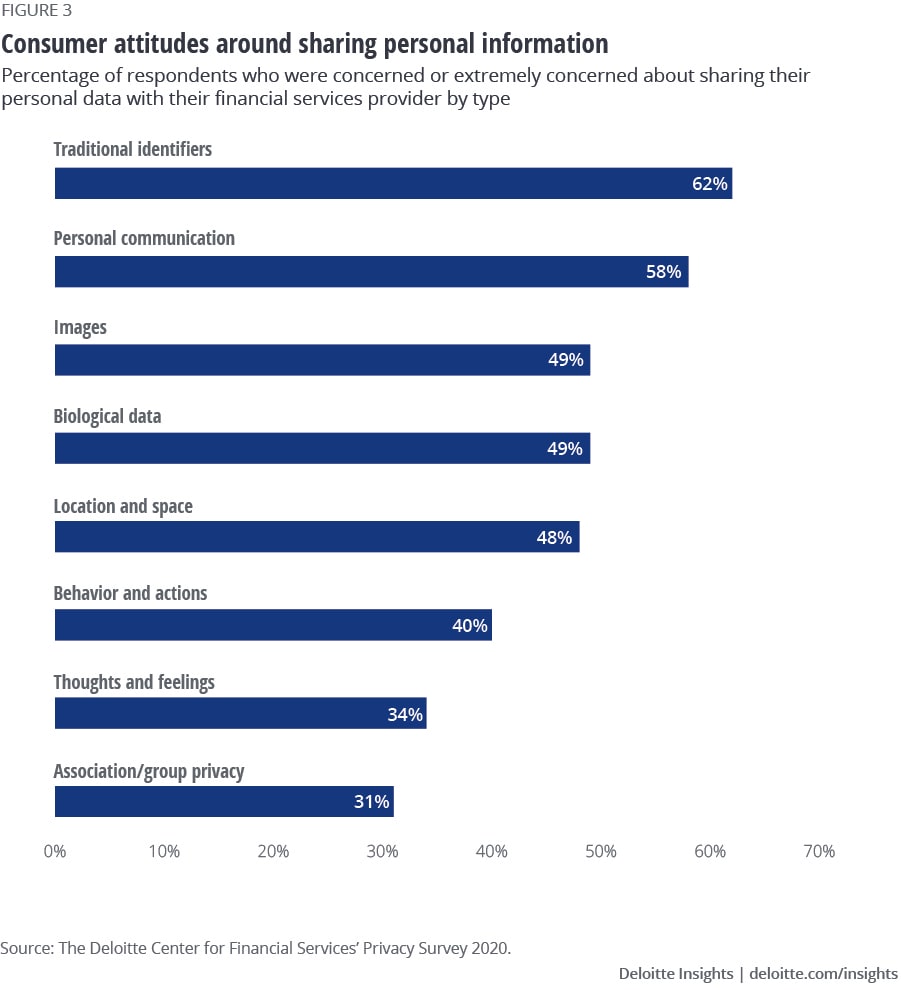

With the eight types of privacy, consumer concern varied across the board (figure 3). More than six in 10 respondents said they are concerned or extremely concerned about sharing personal identifiers (for example, their name and Social Security number) with their financial provider, even though nearly every financial institution collects this information to conduct routine transactions. The next type of information that surveyed consumers found most concerning was records of communication (such as emails, text messages, and phone records). On the opposite end of the spectrum, fewer respondents expressed concern over sharing information around their thoughts and feelings on a variety of topics and memberships/associations (such as work-related groups, religious groups, or political affiliations.)

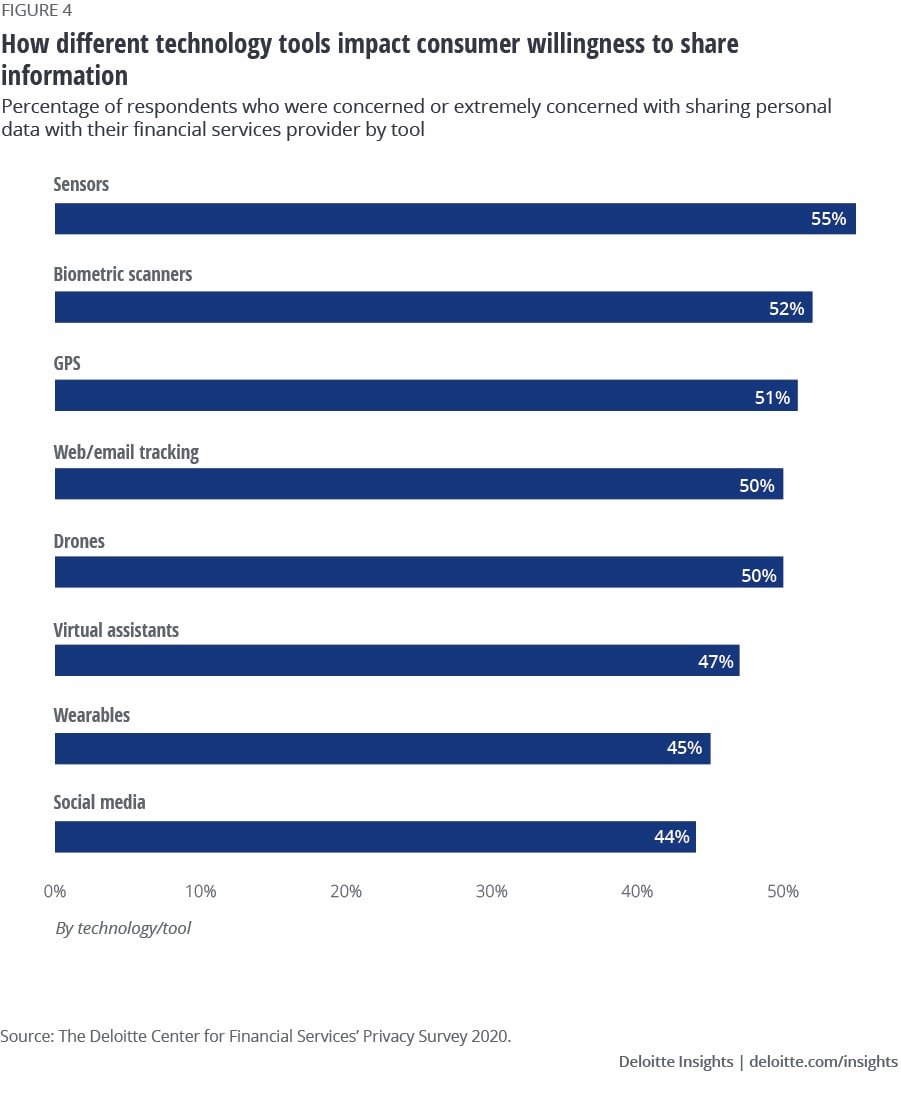

However, respondents’ level of concern among the types of technologies and tools financial institutions use was comparable across each type (figure 4). This may indicate that consumers do not fully understand how financial providers could use these various tools and technologies to collect data.

With these findings in mind, and given the multifaceted nature of privacy concerns, financial institutions undoubtedly have a high bar to clear to put consumers at ease and gain their trust.

Some consumers are willing to exchange data for value

Despite their multifaceted concerns and heightened sensitivity around privacy, security, and data collection and sharing, survey responses revealed that many consumers indeed would be willing to provide access to more information—under the right conditions.

These trade-offs, however, appear to vary by the type of data collected, the financial product involved, as well as certain demographic differences, such as gender and age.

We performed a conjoint trade-off exercise to determine exactly which types of data respondents would be willing to provide in return for added value.

Consumers tend to be least sensitive about sharing location data

Among all types of data, sharing location data—where consumers go and when— seemed the least objectionable to respondents. For example, 56% of respondents with auto insurance were willing to provide live location data for their vehicles to help insurers better assess their risk factors, if offered a premium discount or deductible reduction in return. That rose to 61% among those who are 25-39 years old and jumped to 69% for those between 40 and 56, while dropping to 48% for respondents 57 and older. There was a gender gap as well, with 61% of men surveyed open to such a deal, versus only 50% of women. This trend was even more pronounced when combining age and gender, with men between 40 and 56 more likely (74%) than women (60%) to make this trade-off.

Location data is a valuable asset for other segments of financial services as well. Sharing location was not an issue for many credit card holders surveyed if it resulted in lowered fees or interest rates, with 59% open to such tracking at all times—a segment that remained steady by gender and age. Among those 57 and older, 70% of respondents were amenable to being monitored if they received benefits in return.

Banks can make use of location data in a number of areas, such as fraud detection, by syncing up where a customer’s phone happens to be versus where their credit card is being used. Meanwhile, investment management firms are using geolocation data to help make investment decisions based on aggregated foot traffic in retail outlets and restaurant chains.3 However, investment account holders do not appear as keen on sharing location data: Only 27% of respondents overall stated they would agree to full-time tracking, including only 17% among those 57 and older.

Our survey detected greater resistance among certain segments when auto insurers sought more than just location information. While about 55% of those between 25 and 56 were willing to have their driving be monitored in terms of speed, turning, and braking, along with what they do while driving (such as talking or texting on the phone), only 20% of respondents 57 and older would agree to that level of surveillance, no matter the benefits offered. Gender responses tracked with age, but overall, women (46%) were less open to sharing driving behavioral and performance data than were men (53%).

Biometric data may be the most challenging ask

Asking for biometric data (which was only asked of respondents with auto insurance) appeared to be the most concerning to respondents among all the elements we tested. Only 25% of respondents would be willing to limit access to their vehicle by providing an iris scan or fingerprint to start their car, even though these technologies could help prevent theft or keep uninsured drivers from getting behind the wheel.

Yet the overall number ticked up to 38% if physical condition (such as respiration, heart rate, or blood alcohol level) was also being monitored. This suggests that many consumers may consider health-related monitoring a good personal safety feature. Still, the offer appealed mainly to respondents between 25 and 39 (at 44%). Acceptance dropped to 35% for anyone between 40 and 56, and was only 25% for those 57 and older. There weren’t any gender differences except when combined with age: Among respondents 57 and older, women (24%) were less likely than men (37%) to sign on.

The situation gets more complex when we combined different types of data requests. Allowing access to location, driving behavior, and biometric data, which could potentially offer a greater total benefit to the consumer, was acceptable to 53% of all respondents. Age played a major part, however, as 76% of those between 40 and 56 were open to such a wide-ranging package, versus only 13% of respondents 57 and older. Men (55%) were more likely than women (47%) to take on the full data-sharing agreement. Yet acceptance levels were higher all around if biometric data requests were excluded, leaving only driving location and behavior monitoring.

Social media monitoring is often a deal breaker

Monitoring social media could help financial services firms in risk assessment or preference profiling. They could gain potentially valuable information, such as complaints posted about their company or competitors, evidence of behavior such as heavy drinking or reckless driving, or identification of environmentally focused customers for firms marketing sustainable investment products. But our survey revealed this type of monitoring can be a sore point, at least among credit card and investment account respondents.

For credit card holders surveyed, only 37% were willing to share their posts, comments, and “likes” about financial products and services. There was a big gender gap in willingness between men (46%) and women (31%), as well as a generation gap (only 22% for those 57 and older, versus 39% for the 40–56 segment and 46% for those 25–39). On the investment side, even fewer (24%) were willing to share social media information, including only 19% of women and just 12% of those 57 and older.

Consumers seem lukewarm on web and email monitoring

A pitch offering lower credit card rates and/or fees in return for access to web browsing/shopping activity on all devices was acceptable to 42% of the overall respondent pool. But age again played a factor: Only 28% of respondents 57 and older would go along, versus 50% of those between 25 and 39 and 45% of those in the 40–56 age group. There was also a significant difference in willingness between men (50%) and women (36%).

For financial firms, in some cases, it may not hurt to ask for certain data—even sensitive material—if there is compelling value offered in return. For instance, about 41% of credit card respondents indicated they would be okay with their credit card issuer monitoring their email communications with other financial institutions if they were then offered additional benefits. Acquiring this data might help firms identify emerging and unmet customer needs and provide intelligence on potential cross-selling opportunities.

Still, once again there was a big age difference (23% of those 57 and older versus 48% between 25 and 39, and 41% between 40 and 56), as well as between men (49%) and women (33%). Among investment account holders, only 28% of those surveyed would go along with email monitoring, including just 17% of those 57 and older, compared with 35% of those between 25 and 39.

Enhancing privacy policies could expand data-sharing

Overall, our survey indicates that respondents across segments would be willing to trade data access in exchange for added value, but only under the right circumstances. For example, survey responses indicated that customers would likely be more willing to share their data if they are told clearly what’s being asked of them and why. Given the emphasis on control of their personal information, most surveyed consumers indicated they would want to be given the final say over what kinds of data can be collected and how it may be used or shared with others. Last, but perhaps most important, most consumers cited expecting a compelling benefit in return.

The major challenge, then, will not be how financial institutions can better micro-target specific demographic and even psychographic groups. Instead, they likely need to reinvent their privacy program infrastructure to reach and convince a wider array of customers to enter into a more interactive, symbiotic, and mutually beneficial relationship. They should start by reimagining the purpose and execution of privacy policy statements.

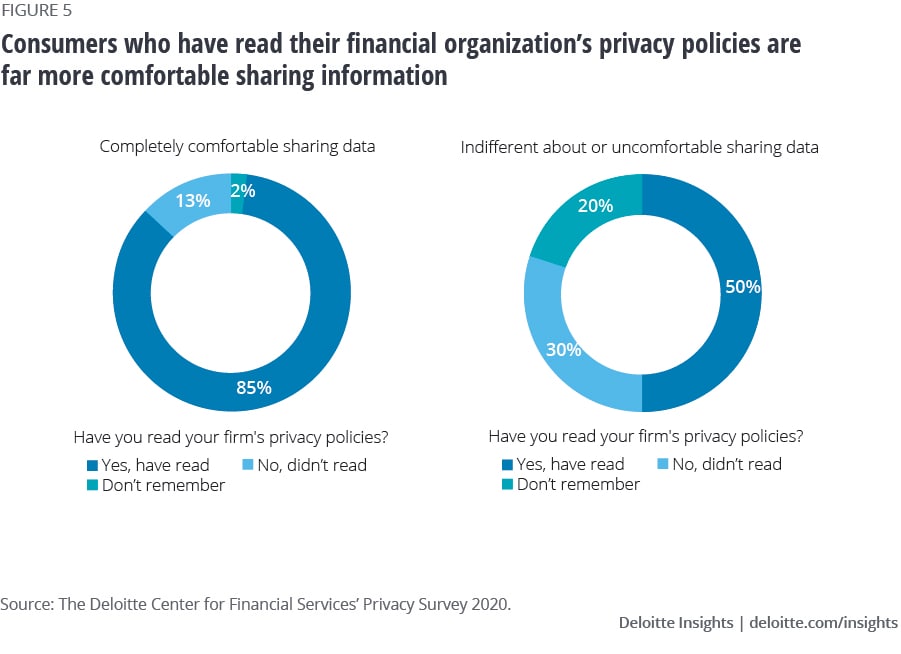

At present, the survey revealed that only 54% of respondents had read the privacy policies of their financial institution, while 28% had not and 18% did not recall. Of those who read the policies, only slightly more than one-half understood them completely. This suggests that privacy policies are likely not having the intended effect: consumers reading and understanding how their data is collected, used, and shared with third parties.

This is a fundamental problem and a lost opportunity. For example, our survey research indicates that there is a strong association between reading policies and comfort level in sharing data with third parties. Among those who are completely comfortable with their financial institution sharing data, 85% of respondents had read the firm’s privacy policies. That compares with just 50% among those who are indifferent/uncomfortable (figure 5).

Imagine how much more might be achieved if financial institutions went beyond check-the-box regulatory compliance requirements with their privacy policies. What if, instead, they worked to build more robust policies that were easier for customers to read and understand? This appears to be an unrealized opportunity for most financial institutions—but it doesn’t have to be. Privacy policies should be used as a tool to help consumers understand the value of sharing more customer data and how it can be of mutual benefit.

Redesigning privacy programs can enable differentiation

Our research indicates that current privacy practices among some financial firms fall short in engaging with consumers. To thrive in the digital age, insurers, banks, and investment management firms should think bigger, as well as be bolder and more proactive in communicating and giving value back to customers. Instead of viewing privacy as a check-the-box regulatory activity, firms should consider this an opportunity to invest in a world-class privacy program that offers customers a comfortable, secure environment and, in turn, engenders greater trust and cooperation.

To accomplish this, financial institutions can consider the following: (a) communicate more frequently and interactively; (b) be clearer about the data being collected and why; and (c) offer consumers more control in deciding what and how to share, and under what conditions.

Designing the optimal solutions may be easier said than done, since trade-offs vary by type of data and customer segment. Given this, financial services firms should consider conducting holistic research to gain insights about how trade-offs may apply to their products and customer segments. There may not be one universal, one-size-fits-all solution.

Financial firm leaders should be deliberate in choosing what data to pursue and how, keeping in mind that some data is harder to get customer buy-in for than others. Essentially, they should think through the privacy implications versus the value being offered in return.

To accomplish this transformation, financial firm leaders should ensure each function within the institution plays a key role in making privacy management a core competence. This new approach can only become a reality when privacy goes beyond the information security and compliance functions. While specific roles may differ, privacy should become everyone’s responsibility, and embedded in almost every customer-focused activity within the institution.

Here is a functional breakdown of how this transformation could occur:

Marketing. The marketing department should ensure that trust is established through clarity and transparency of privacy-related communications. Marketers should ensure consumers feel in control of their own data. Offering consumers the ability to change their preferences depending on the context and their own personalized needs can be critical to achieving this goal. Last but not least, marketers should work with the lines of business and financial leaders to ensure consumers are being offered compelling value.

Third parties/intermediaries. Similar to how financial institutions handle cybersecurity, another area of focus should be how third parties and intermediaries deal with customer privacy. Financial services firms increasingly rely on third parties to collect data and communicate the value in sharing more customer data, so it is critical that financial institutions ensure these partners have privacy practices that are in line with the firm’s framework. Perhaps these privacy-related expectations could be built into agreements/contracts, beyond data security.

Risk. The risk function should also weigh in. But it should work with other business groups to determine the appropriate risk-return trade-offs that the institution is willing to make in collecting customer data, and in deciding the value exchange it can offer, whether in new product development or in the adoption of new tools and technologies for data collection.

Compliance. Compliance is expected to continue to play a major role in privacy management. But the compliance function will likely need to accommodate and welcome a more expansive, integrated, and strategic approach to meet the future demands of the digital age.

Chief privacy officers should play a critical role in making privacy a strategic priority. They should also be empowered to become the orchestrators of the new approach we outline in this report.

Our research has focused on why it’s necessary and important for financial services firms to adopt a more sophisticated and nuanced approach to privacy management. But that’s not the only reason to act. Creating a robust privacy program that allows firms to partner with customers in mutually beneficial ways could be a competitive differentiator, engendering greater trust, loyalty, and cooperation. And while the industry is still grappling with formidable pandemic-related challenges, now may be the perfect time to reimagine and redesign customer privacy programs to enable value exchange.

Appendix

Methodology

We surveyed 2,000 US adult consumers who have either a credit card in their name, an investment account in their name (a brokerage or retirement account), or are the primary policyholder of auto insurance. We received a nearly equal distribution of men and women respondents, with ages spread among 18–35, 36–56, and 57+ years old. At least one-half of respondents said they were active on social media. The survey also included three separate conjoint exercises covering auto insurance, credit cards, and investment accounts to measure how consumers make trade-offs between the types of data they share and benefits they receive in return.

More from the Financial services collection

-

Insurers step up as financial first responders Article4 years ago

-

Opportunities for private equity post-COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

Potential implications of COVID-19 for the insurance sector Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the investment management industry Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 potential implications for the banking and capital markets sector Article4 years ago