Beyond the EHR Shifting payment models call for hospital investment in new technology areas

13 minute read

11 January 2019

Many health systems seem to be waiting for the tide to shift to value-based care before adopting technology that will support new payment models. But waiting to invest could put health care organizations at risk of falling behind.

Executive summary

What kinds of technology are health systems investing in, and do investments vary depending on whether they have more payments based on quality and value?

To answer this question, Deloitte researchers analyzed data from approximately 4,500 US hospitals between 2012 and 2016. Two notable findings emerged:

- Hospitals with more payments based on quality and value were more likely to adopt technologies for population health and care coordination, data aggregation and management, and reporting and analytics.

- Few hospitals have been investing in patient and provider engagement technologies or core applications that support operational and financial aspects of their business (such as supply chain management and revenue cycle management). For these kinds of technologies, we did not see differences in adoption based on the share of payments based on quality and value.

Learn more

Explore the Health care collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

As hospital revenue tips more toward payments based on outcomes and risk and more consumers show an interest in taking their care into their own hands, health care systems—even those mainly working in traditional payment environments—should go beyond the electronic health record (EHR) to meet the demands of the new market. They should consider investing more in technology that supports patient and provider engagement and core applications. They may also need to make significant upgrades to core systems to adopt the capabilities required to manage downside risk under these new contracts. More recent evidence suggests that some leading health systems are investing in these areas as they gain more experience with new payment models.

Introduction

Several trends are causing health systems to adopt technology-enabled solutions to minimize cost and improve value. And, in response to rapidly changing consumer demands, many health systems are focusing on factors beyond price and quality to create customer-centered business models. Technologies such as EHRs and patient portals are often a key component of such strategies.

Many health systems are facing a margin cliff as the aging of the US population combined with lower reimbursement from government payers put pressure on traditional revenue sources.1 This, combined with reporting requirements under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), has contributed to hospital consolidation in recent years. Health systems’ ability to succeed and realize value after a merger or acquisition can largely hinge on capabilities to effectively collect, understand, and act on information.

The evolving market shift from payments based on volume toward payments that emphasize outcomes and risk is one of the largest drivers of technology adoption. Health systems need to derive meaningful information from data to monitor patients and reward providers throughout the care journey. New ways of collecting, processing, and analyzing data, coordinating care in and out of the hospital setting, and supporting clinicians throughout the care journey can be therefore critical.

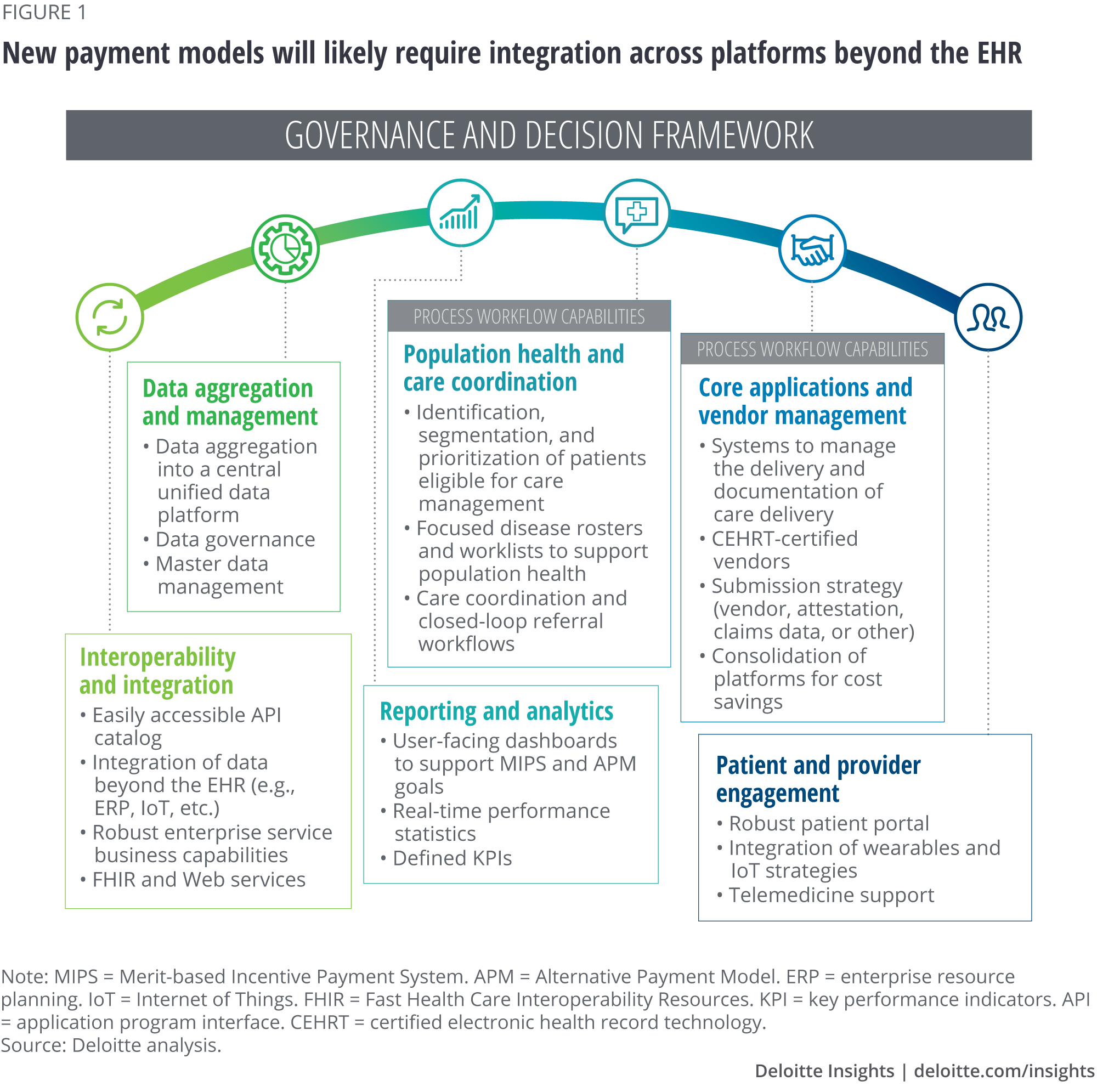

While 96 percent of hospitals have adopted EHRs, the shift to value-based payments will likely require integration across platforms beyond just the EHR.2 Consider the governance and decision framework in figure 1. Hospital technology strategies should reach across these different functions to support an enterprisewide strategy. For example, interoperability and integration will become increasingly important as consumers demand that their information be portable and as care coordination becomes a central feature of new payment arrangements.

Many health systems are already experiencing a shift in consumer demand. For instance, more than half of Kaiser Permanente’s 12.2 million patients are registered on Kaiser’s member website where they can view lab test results, fill prescriptions, send secure emails, request appointments online, and consult with doctors over video. Virtual interactions with patients rose from 56 percent of total interactions in 2015 to 59 percent in 2017.3

Are health systems responding appropriately as the move toward new payment models speeds up?

Deloitte Center for Health Solutions researchers used data from a sample of approximately 4,500 US hospitals to explore to what degree the shift in payment incentives drove technology adoption between 2012 and 2016. We focused our analyses on two central questions:

- Were hospitals that receive a higher share of revenue from quality and value contracts more likely to adopt technology that supports new required capabilities?

- Which technologies were hospitals with quality and value incentives more likely to adopt?

After dividing the hospitals into two groups (see sidebar, “Stratifying hospitals”), we ran regression analyses to understand the relationship between hospitals’ focus on quality and value contracts and their adoption of different technologies using the governance and decision framework in figure 1. To learn more about the methodology, see the appendix.

In the regression models, we controlled for hospital characteristics such as size, ownership status, system affiliation, and case and payer mix, as well as unobserved differences in local market conditions and common time trends such as those stemming from demographic changes and meaningful use incentives.

Stratifying hospitals

Based on their revenue from quality and value contracts (such as bundled payments and global risk capitation) we classified hospitals into two groups:

- Hospitals with no incentives. Those that have no revenue from such contracts (88 percent of the sample)

- Hospitals with incentives. Those that receive some fraction of their total revenue from such contracts (12 percent of the sample)

Hospitals with incentives were more likely to adopt some of the six technology functions4

Our analyses reveal that between 2012 and 2016, quality and value incentives were strongly associated with the adoption of certain data-related technologies, particularly those pertaining to population health and care coordination, data aggregation and management, and reporting and analytics. Notably, we found that hospitals with and without incentives did not differ in their adoption of patient and provider engagement technologies, nor in the adoption of most of the core applications that support operational and financial aspects of their business, such as supply chain management and revenue cycle management (figure 2).

Hospitals with incentives were more likely to adopt population health management, as well as clinical analytics and reporting technologies

Regression analyses performed on each individual technology within the six overarching technology functions show more nuanced trends in adoption across hospitals with and without incentives.

Population health management

Hospitals with incentives were more likely than hospitals with no incentives to have adopted population health management technologies, but less likely to have adopted case mix management technologies. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the adoption of patient acuity, outcome and quality management, and clinical decision support technologies (figure 3).

Investment in population health management solutions can pay off in many ways. In 2009, Adventist HealthCare partnered with Conifer Health Solutions to overhaul its population health management approach. Conifer’s solution helped Adventist identify high-risk patients, connect them with primary care physicians, and assign a care management nurse to oversee outreach and care plans. After a year of implementation, the health of nearly half of the targeted patients improved and they moved out of the high-risk category.5

Reporting and analytics technologies

Hospitals with incentives were more likely than those without incentives to have adopted clinical analytics and reporting technologies. Our analyses showed no significant difference between the two hospital segments in their adoption of finance-focused technologies, such as business intelligence and data warehouse mining (figure 4).

Anecdotal evidence suggests that leading health systems’ investments in emerging technology solutions to support clinical data warehouse mining have begun to pay off. For example, researchers at Johns Hopkins created a machine learning model to predict which patients were most at risk for developing sepsis. Their model took 54 medical measurements and built a scoring system for identifying patients. Furthermore, they accounted for missing data and notified physicians only when a threshold of certainty was reached in order to avoid false positives. Approximately 300 doctors tested the software and within a year of use, they saw a 75 percent drop in calls to the Rapid Response Team (teams that are brought in to quickly treat sepsis; but often, by the time they are alerted, it is too late to save the patient).6

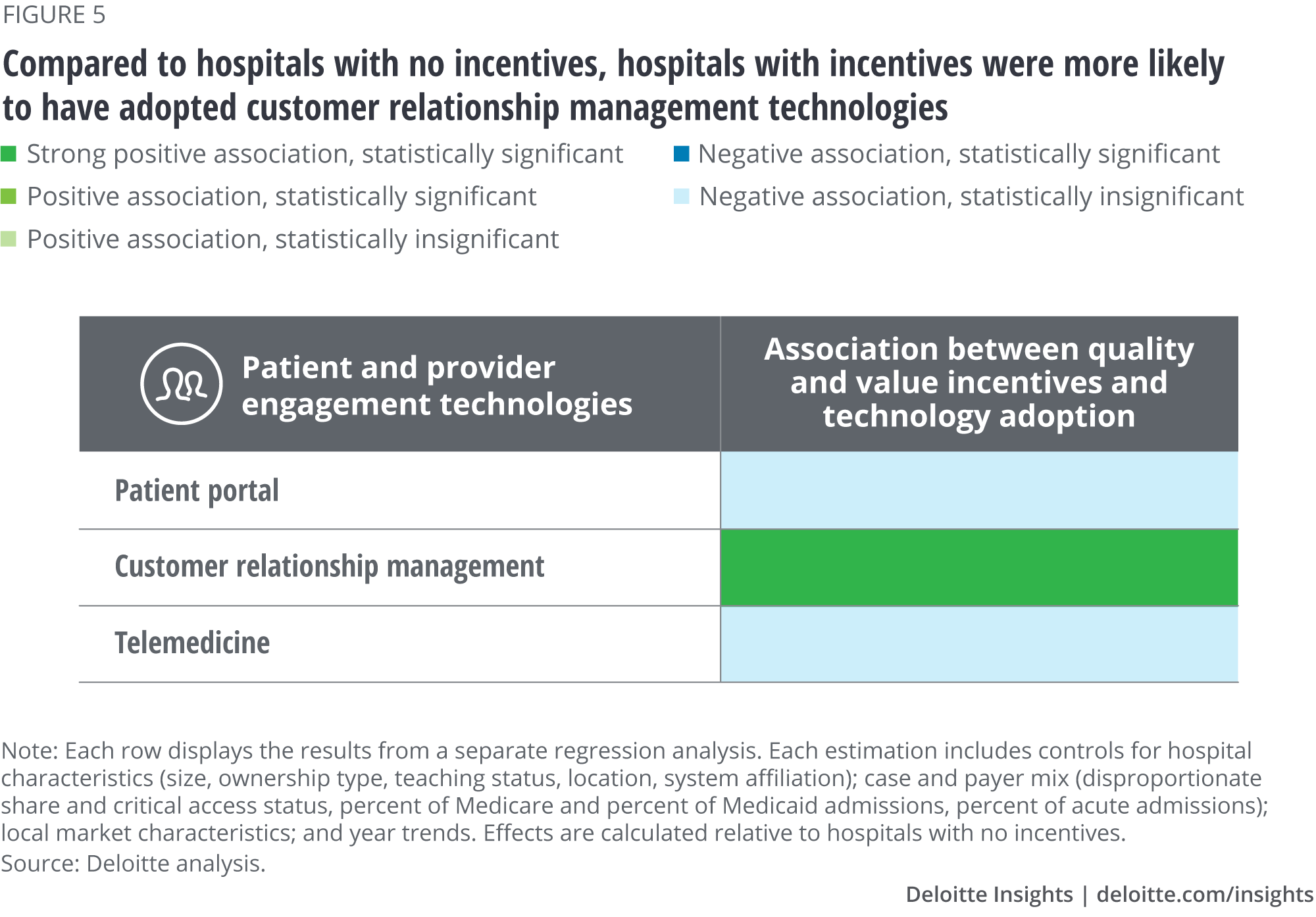

Overall, hospitals with incentives were not significantly more likely to adopt patient and provider engagement technologies

Our analyses also reveal that as of 2016, hospitals with incentives were not significantly more likely to adopt patient and provider engagement technologies. This trend was observed both overall and within individual regression analyses. Within this function, hospitals with incentives were more likely to adopt only one of the three technologies: customer relationship management (CRM) (figure 5).

One explanation for this could be that many organizations view patient and provider engagement technologies as essential for delivering good care in general, and not just in the context of the shift to value-based care. Another explanation is that our data do not go beyond 2016. Health systems have rapidly adopted new technologies and moved more deeply into value-based care over the last several years. It could be that, at the time, these technologies were less mature and few systems had enough revenue under risk-based contracts to substantiate significant investments in these areas.

More recently, hospitals started employing traditional CRM tools in their care coordination strategies. For example, Mount Sinai Health System has partnered with Salesforce to overhaul the way it manages thousands of Medicaid patients. Using Salesforce’s Health Cloud and Community Cloud allows all care providers (such as clinicians and social workers) to see the status of patients in the system. The solution is mobile-friendly and real-time.7

Implications

Moving beyond the EHR

As this data shows, most health systems’ technology adoption strategies are focused on organizing clinical data and information and adopting EHR systems and analytics capabilities to interpret the data. These technologies will likely continue to be critical. But, our analyses also show that many health systems—even ones that are farther along the road to new payment arrangements—may still lack critical technologies. Health systems should go beyond the EHR to focus on patient and provider engagement technologies (such as virtual care) and core operational and financial applications.

Health systems will likely need new capabilities in patient and provider engagement as health care consumers take care into their own hands and as clinicians are paid based on outcomes as well as volume. They may also need to upgrade the patient-facing aspects of the revenue cycle (for example, patient billing and collections) to protect their margins by more efficiently reducing costs and improving revenue. Significant upgrades to financial systems may also be necessary to manage downside risk under these new contracts. Anecdotal evidence from the last several years suggests that many health systems are already shifting their investment focus to these areas.

Understanding the impact of the shift in payments on margins is also important, as many health systems may need the capital to invest in new technologies. Today, many health systems appear to be in a holding pattern, waiting until the tide shifts to begin on the journey toward new payment models. Waiting to invest could put organizations at risk of falling behind on the adoption curve. Health systems should consider accelerating investment strategies now while fee-for-service (FFS) revenue remains a strong contributor to margins. Once the industry reaches a tipping point, revenue based on outcomes and risk could exponentially increase, leaving fewer resources for new investments.

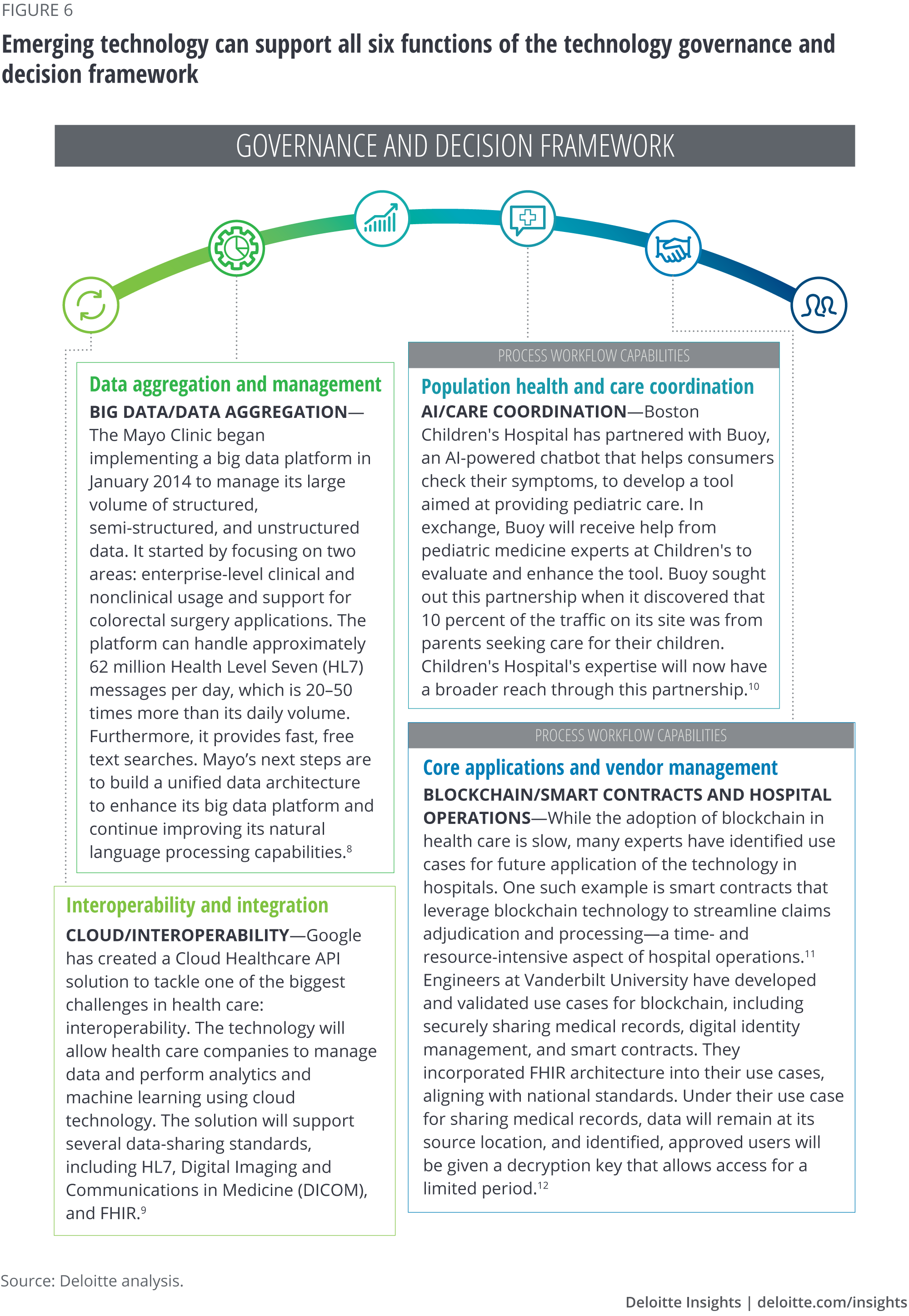

Integrating emerging technology into the framework

New and emerging technologies, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and blockchain, will likely play an increasing role in supporting the capabilities needed under new payment models. Many health systems are already using these technologies to support key business and clinical decisions (figure 6).

Appendix: Methodology

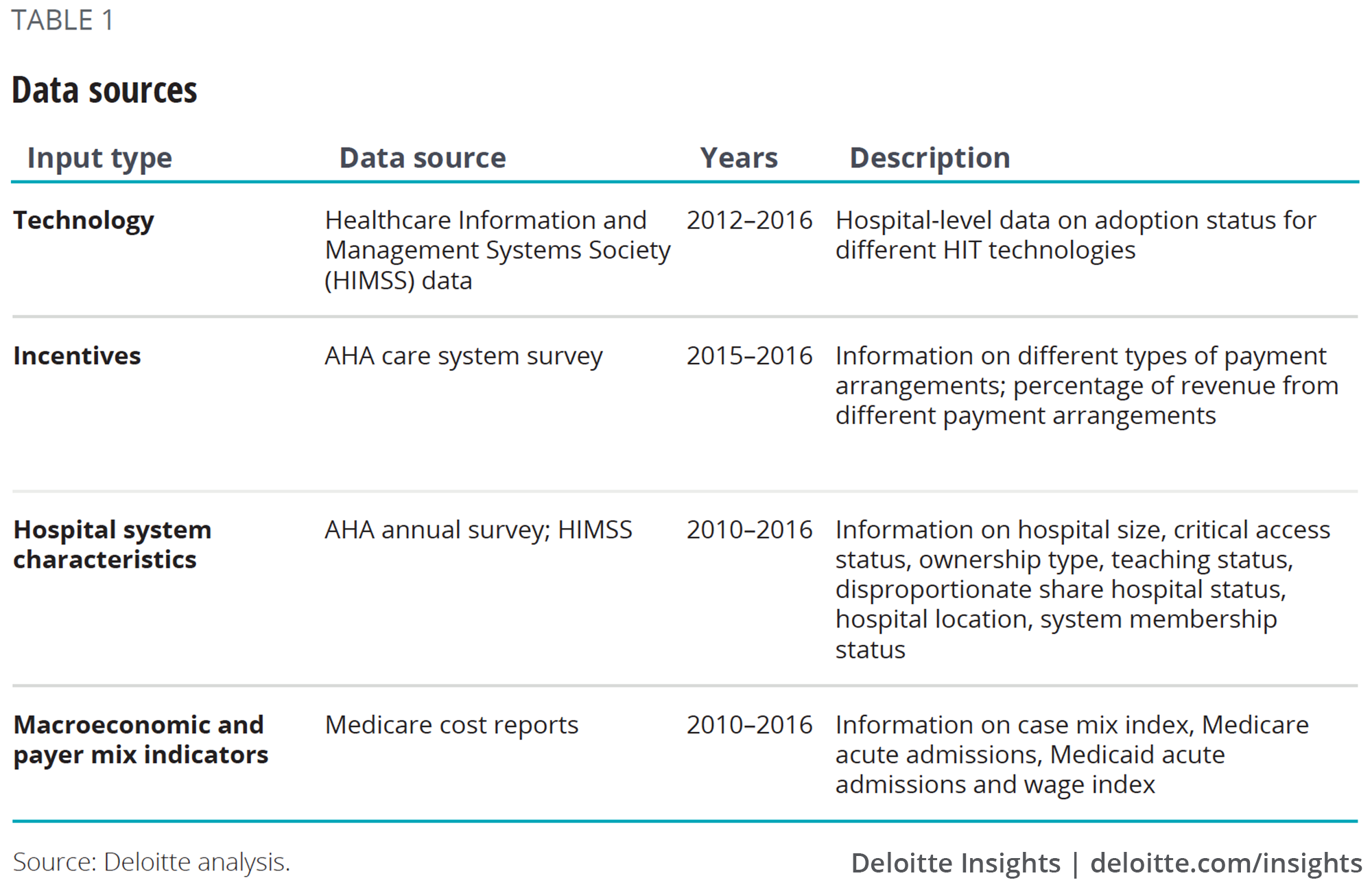

Data sources

The regression analyses included data from the sources shown in table 1.

Method of analysis

The analysis consisted of three steps:

Stratify hospitals

We classified hospitals into two categories based on the net patient revenue reported from arrangements that tie payment to performance. Hospitals that did not report earning any revenue from these models were treated as the base category.

The data we used for this analysis does not include information about the types of risk arrangements that hospitals have adopted. For example, we cannot tell whether hospitals are in upside-only or downside arrangements. This is the reason why we stratified hospitals as those with no incentives and those with incentives.

Group technologies into functions

The HIMSS survey defines 41 separate hospital technologies, which we grouped into six overarching technology functions:

Patient and provider engagement technologies: Patient portal, customer relationship management, telemedicine

Core technologies:

- EHR: Emergency department information system, clinical documentation, physician documentation, electronic medication administration record (EMAR)

- Supply chain management technologies: Asset tracking, pharmacy management system, real-time location solution (RLTS), material management

- HR & administration technology: Payroll, personnel management, time and attendance, benefits administration, staff scheduling

- Revenue cycle management technologies: ADT/registration, medical necessity checking content, credit/collection, cost accounting, budgeting

- Other core applications and vendor management: Electronic resource planning: patient scheduling, patient billing, bed management

Patient health and care coordination technologies: Case mix management, patient acuity, population health management, outcome and quality management, clinical decision support system, vendor: contract management

Data aggregation and management technologies: Clinical data repository, enterprise master person index, document management

Reporting and analytics technologies: Financial—business intelligence, clinical—business intelligence, financial—data warehouse mining, clinical—data warehouse mining, electronic forms management

Interoperability and integration technologies: Health information exchange (HIE), electronic data interchange (EDI)

Run regression analyses

We ran probit models at both the technology and the function level. We controlled for hospital and area characteristics (hospital size, critical access status, ownership type, teaching status, disproportionate share hospital status, hospital location, system membership status, and hospital referral region (HRR)) as well as payer-mix indicators (case mix index, Medicare acute admissions, Medicaid acute admissions).

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more Deloitte Health Care Content

-

Health care Collection

-

Electronic health records Article6 years ago

-

Surveys of health care consumers and physicians Collection6 years ago

-

Social determinants of health and Medicaid payments Article6 years ago

-

Physicians are willing to manage cost but lack data and tools Article6 years ago