Social determinants of health and Medicaid payments Steps states can take to factor social determinants of health into Medicaid payment policies

08 November 2018

States that can successfully factor social needs into their health care payment policies may see health and well-being improvements among citizens while helping reduce health care utilization and spending.

Greater use of the emergency room has been linked to homelessness,1 diabetes-related hospital admissions have been attributed to food insecurity,2 and social isolation has been identified as a risk factor for stroke and heart attack.3 These are just a few of the ways in which the social determinants of health (SDoH) contribute to health outcomes, health care utilization, and spending. These determinants, which include social, economic, and environmental factors such as income, housing, transportation, and education, account for roughly 20 percent of premature deaths in the United States.4

Learn more

Read more from the Government and public services collection

Explore the Health care collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

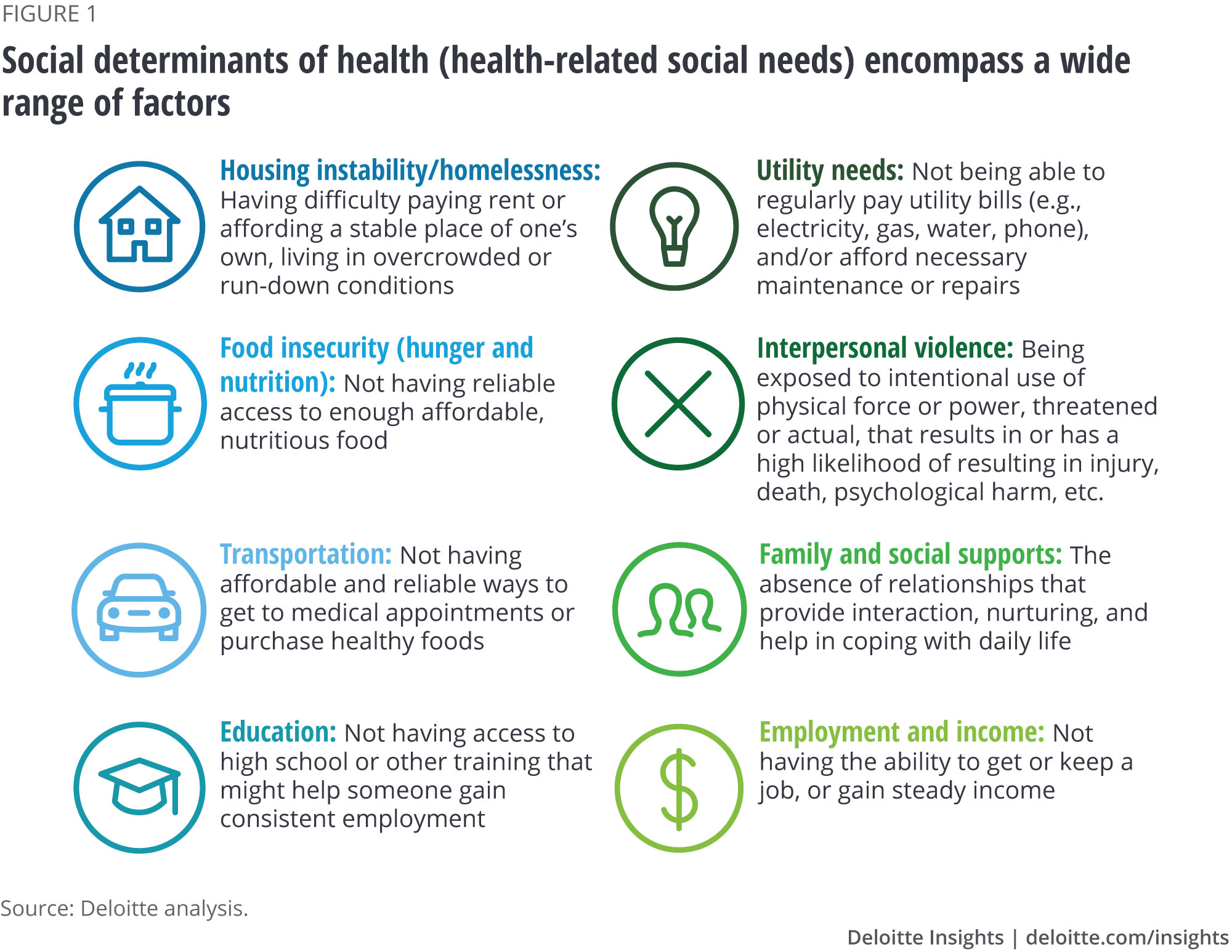

Increased awareness of how SDoH can affect health outcomes has prompted many practitioners and policymakers to rethink health care delivery—especially for Medicaid beneficiaries, whose low incomes typically make them disproportionately likely to have health-related social needs.5 In fact, there are a number of broad-scale efforts now under way to identify and direct resources toward individuals with social needs. For example, some states are beginning to require managed care organizations (MCOs) to screen enrollees for social needs. Meanwhile, some providers and plans around the country are working with community-based organizations (CBOs) to link individuals to resources such as food pantries, housing supports, and transportation assistance.6 (For more information about social determinants of health, see figure 1.)

But another powerful, largely untapped way states can address social needs is through payment arrangements with MCOs, which cover nearly two-thirds of Medicaid beneficiaries nationwide.7 States that can successfully factor social needs into their health care payment policies with MCOs may begin to see significant improvements in the health and well-being of individuals who face socioeconomic and environmental challenges and help reduce avoidable health care utilization and spending.

In this article, we discuss two complementary strategies states can use to address SDoH among Medicaid beneficiaries: risk adjustment and pay-for-performance (P4P). Both strategies are directed at MCOs. By factoring social needs into risk adjustment formulas, states can ensure that MCOs that have more members with social needs receive more money to take care of those members. This strategy also provides MCOs with the incentive to assess their members for social needs and capture data that can be shared with, and useful to, the state. Incorporating social needs measures into managed care P4P arrangements can help states develop, implement, track, and measure the impact of interventions that address health-related social needs.

Because these strategies will require careful data collection and evaluation, it is unlikely states will be able to implement them immediately. But they can start on the path now. In this article, we outline the steps states can take to achieve these longer-term policy goals.

Accounting for the social determinants of health in risk adjustment

Under a managed care arrangement, a state pays a capitated rate—a fixed fee to an MCO for each person enrolled in the plan—and the MCO assumes the total cost of care for its population of Medicaid beneficiaries.8 States have traditionally considered age, gender, eligibility category, and region/locality when setting capitation rates. However, because financial risk varies based on the health of individuals covered by different MCOs, several state Medicaid programs apply risk adjustments to these capitation rates to offset the difference in cost between MCOs of providing health insurance for individuals who represent a relatively high risk to insurers. Under risk adjustment, an insurer who enrolls a greater than average number of high-risk individuals receives compensation to make up for extra costs associated with those enrollees. These risk adjustment models often account for enrollees’ medical histories and factor in chronic conditions, which tend to be strong predictors of care needs and expenditures.9 States typically gather health status information from medical claims, encounter data, and pharmacy data.10

Though research demonstrates that socioeconomic status and social needs can influence health care utilization and expenditures, risk adjustment models typically do not account for these factors. Massachusetts is a notable exception (see sidebar, “Massachusetts incorporates two social indicators into their risk adjustment formula”). By incorporating social determinants into risk adjustment formulas, states can improve the accuracy of the relative rates they pay their MCOs while also providing MCOs with the incentive to assess their members for social needs and capture data that can be shared with the state and used to inform social interventions.

Massachusetts incorporates two social indicators into their risk adjustment formula

In 2016, Massachusetts implemented a new Medicaid payment model that incorporates housing indicators and neighborhood stress scores into its MCO risk adjustment formulas. In this state’s model, individuals who have had three or more addresses in a single calendar year, or individuals who are coded as “homeless” in a medical encounter record, increase an MCO’s risk score, resulting in higher payments to the plan. Neighborhood stress scores include a composite measure of “financial stress” from census data, based on addresses that are geocoded to the census block group or tract.11 Enrollees who live in neighborhoods with higher-than-average stress may also trigger higher payments for MCOs. Early evaluations of the Massachusetts model have found that adding social determinants and related variables to risk scores strengthens the predictive power of risk adjustment and yields more accurate payments to MCOs.12

Steps states can take to incorporate SDoH into risk adjustment models

A risk adjustment model could include factors such as housing instability, financial stress, food insecurity, social isolation, and low educational attainment. To date, no state has incorporated a robust set of SDoH-related indicators into its risk adjustment models. There are several possible reasons for this.

First, since not all MCOs screen for social needs, states may lack data on such needs. Second, even when MCOs collect SDoH data, the screening tools organizations use can vary widely. They may be collecting different indicators, or two MCOs may define the same indicator in different ways. For example, one organization may define housing instability as chronic homelessness, while another defines it as frequent changes of address. Because risk adjustment models attempt to capture the relative risk of the population across organizations, MCOs must use the same indicators, defined in the same way, to make their comparisons. Without standardized definitions and data collection, states could struggle to develop and apply sound risk adjustment formulas.

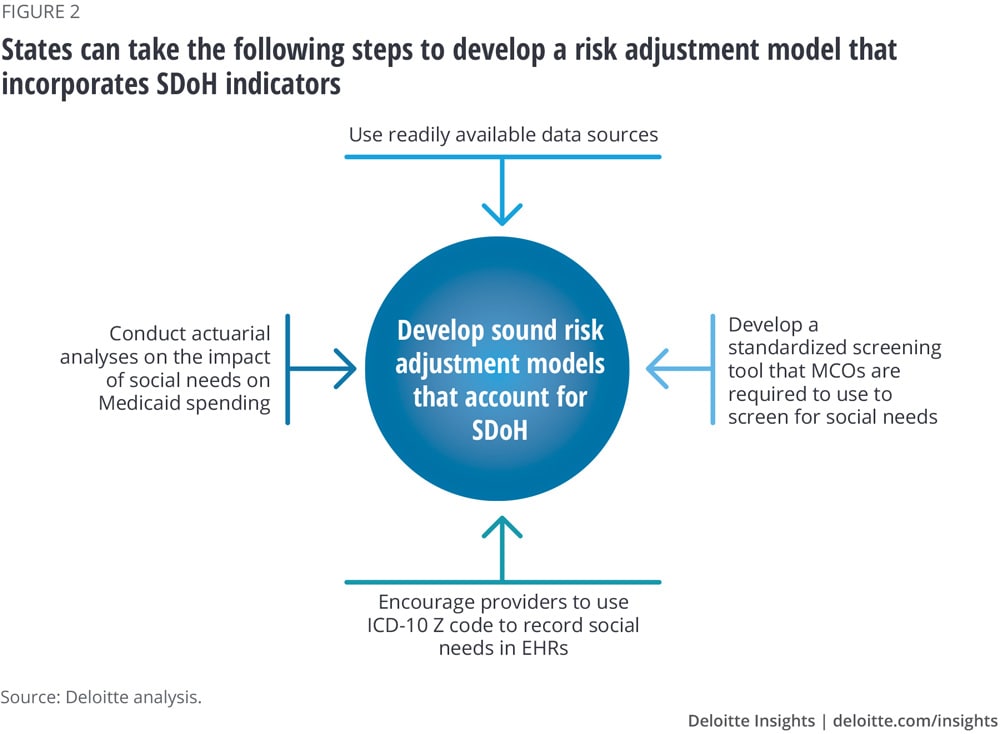

Despite these barriers, states can take several immediate steps to lay the groundwork for a risk adjustment model that considers a robust set of SDoH indicators (see figure 2).

- Use readily available data sources. While some SDoH data can be difficult to collect, states can find other individual- and aggregate-level indicators in a host of currently available data sources. These may include unstructured data stored in electronic health records (EHRs); health risk assessments collected by health plans and providers; integrated eligibility systems for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), child care, and Medicaid; and census data. (See sidebar, “SDoH data sources.”) States would need to standardize and integrate this data to make it meaningful, interpretable, and actionable.

- Develop a standardized screening tool that MCOs are required to use to screen for social needs. If all MCOs collect the same indicators, and those indicators define the same social needs in the same way, states would be able to compare populations served by different MCOs in a manner that ensures a fair distribution of capitation payments.

- Encourage providers to use ICD-10 Z codes to record social needs in EHRs. Providers use International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes to add virtually all patient diagnoses to EHRs. While most ICD-10 codes reference clinical conditions, symptoms, or procedures associated with health care delivery, a subset of these codes—Z codes—captures encounters related to social circumstances such as malnutrition or history of criminal conviction.13 Z codes are rarely used today, but they have the potential to serve as a valuable SDoH data resource.14 Recent Deloitte research shows that providers in a fee-for-service system may not have incentives to use the codes, and that state and federal regulations surrounding providers’ ability to collect and share data can conflict, leading to confusion among providers.15 States may be able to encourage the use of Z codes by requiring MCOs to enter into value-based care arrangements with providers, and by clarifying the rules governing providers’ collection and use of social needs data. (For more on Z codes, see the sidebar, "SDoH data sources.")

- Conduct actuarial analyses on the impact of social needs on Medicaid spending. By using available data sources and collecting additional data through a standardized screening tool and Z codes, states could begin to develop a more precise calculation of the relationship between various social needs and Medicaid spending. This, in turn, would refine states’ risk adjustment models over time. Ideally, they would do this work in cooperation with MCOs to keep the process transparent.

Accounting for the social determinants of health in P4P

While accounting for SDoH through risk adjustment may improve the accuracy of payments from states to MCOs and incentivize MCOs to collect data on their members’ social needs, it does not incentivize MCOs to address those needs. To ensure that the needs of beneficiaries are not only identified but met, states can require or incentivize MCOs to implement SDoH interventions. States are beginning to move in this direction: Among the 39 states with comprehensive risk-based MCOs, 19—or roughly one-half—currently require their MCOs to screen for social needs and refer beneficiaries to social services.18 While screening and referrals are an important step, it’s even more important to ensure that Medicaid beneficiaries are actually completing the screening assessments, and that the interventions implemented successfully address social needs. States could use a combination of contractual requirements and incentive payments to achieve this goal.

In existing arrangements with MCOs, states often offer bonus payments or other incentives to MCOs that succeed in measurably improving access to care, disease management, and clinical outcomes. Such P4P arrangements may also reward measurable reductions in preventable health care utilization and total cost of care. To date, however, these quality incentive programs have primarily focused on clinical measures alone.19 By also including SDoH in their P4P initiatives, states could encourage insurers and providers to address the social needs that research has linked to health outcomes.

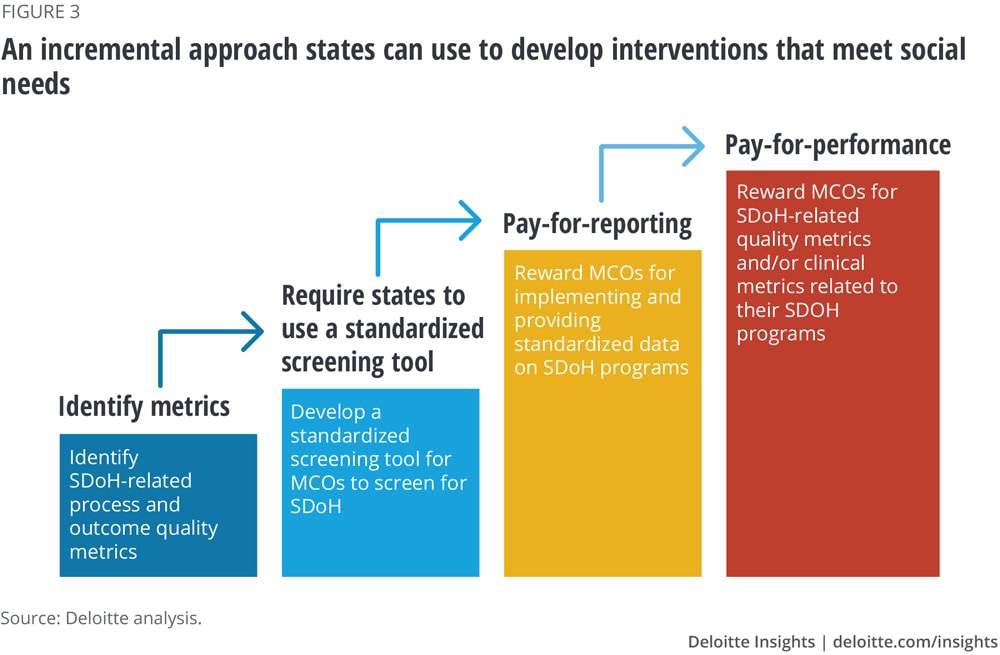

Optimally, states could set up a P4P arrangement that rewards MCOs for demonstrating that their SDoH interventions produce better health outcomes and reduce utilization and spending. It is important for states to recognize that if MCOs are to respond to payment incentives to address SDoH, bonus payments would need to exceed the investment costs. States would also have to rigorously monitor and evaluate these initiatives in order to provide accurate payments; before states can put such measures in place, they would need to standardize a set of quality metrics related to social determinants and assess which interventions work. By taking an incremental approach, states could gradually work their way toward implementing P4P arrangements for interventions that meet social needs (see figure 3).

- Identify metrics. States should identify which process and outcome metrics should be used to evaluate the most effective interventions for specific social needs. Process measures should focus on actions taken by MCOs. For example, they might include the percentage of beneficiaries screened; the number of referrals the MCO makes to resources such as food pantries or job training services (based on identified social needs); or the number of partnerships established with community-based organizations. Outcome measures focus on results. They might include enrolling a beneficiary in a social service program such as TANF or SNAP, helping a beneficiary retain stable employment, or helping a beneficiary find permanent housing. Besides gathering data, states could use existing sources of research and analysis to help determine how different SDoH interventions may affect health outcomes, such as the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps’ “What works for health” tool.20

- Require states to use a standardized screening tool. States should develop or identify a standardized screening tool, potentially incorporated into their integrated eligibility system, and require that MCOs use it to screen Medicaid beneficiaries for social needs. This step could improve risk adjustment, and could be just as crucial for establishing P4P programs. Standardization would enable states to make apples-to-apples comparisons and discover which interventions work for social needs at scale. It could also help ensure that all organizations collect the same indicators, and that those indicators measure social needs in the same way.

- Pay-for-reporting. Before advancing to P4P, states could require MCOs to implement and provide data on programs with clearly defined SDoH goals, target populations, and metrics aligned to the state’s chosen SDoH measures, and in exchange reimburse MCOs for the expected associated costs. Based on the data that emerges from these programs, states could then refine their ideas about which metrics should be used in a P4P initiative and how often MCOs should provide reports. Armed with this knowledge, states would develop P4P initiatives that provide incentives for the interventions most likely to produce the best outcomes.

- P4P. States can link their payments to SDoH interventions and health outcomes in two ways: First, they could give bonus payments to MCOs that exceed benchmarks on state-defined SDoH-specific process and outcome measures. Second, they could tie incentives to interventions that improve health outcomes. States could use related quality measures to evaluate the impact of MCO SDoH interventions. For example, for interventions aimed at food insecurity among beneficiaries with diabetes, states could look for improved diabetes control; for interventions aimed at homelessness, they could seek reduced hospital readmission rates and less nonurgent emergency room visits.

Conclusion

As this article outlines, incorporating SDoH into risk adjustment models can allow states to more appropriately compensate health plans that disproportionately cover populations with a high burden of social needs and incentivize MCOs to collect social needs data on their members. Giving MCOs incentives to address Medicaid members’ social needs through an incremental approach that culminates in P4P or contractually requiring them to do so can enable states and MCOs to better understand the links between social needs and health, and develop programs that effectively address those needs.

More broadly, if states incorporate SDoH into their health care payment policies, they can better address the socioeconomic barriers their citizens face, improve citizens’ health, and reduce avoidable health care utilization and spending. The step-by-step strategies outlined in this article can help states begin their journey toward achieving these goals.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.