Equipping physicians for value-based care What needs to change in care models, compensation, and decision-making tools?

11 minute read

15 October 2020

Mark J. Bethke, FSA, MAAA United States

Mark J. Bethke, FSA, MAAA United States Dr. Randolph Gordon, MD, MPH United States

Dr. Randolph Gordon, MD, MPH United States Natasha Elsner United States

Natasha Elsner United States Hemnabh Varia India

Hemnabh Varia India

Value-based care is a critical part of any health care organization’s short and long-term strategy to contain costs and enhance quality, but data trends suggest change is slow. Discover the essentials for successfully reorienting physicians from volume to value.

Executive summary

Value-based payment models are designed to reduce spending while improving outcomes. Compared to fee-for-service (FFS), these models place greater accountability for clinical and cost outcomes on organizations and/or individual practitioners delivering care.

Learn more

Explore the health care collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app.

Even as health systems have been gradually adopting more contracts incorporating value-based care metrics on cost and quality, the data from our nationally representative physician survey shows slow progress on developing essential capabilities for value-based care: physician compensation, tools for decision-making, and care models.

We have analyzed trends from the Deloitte Survey of US Physicians from 2020, 2018, 2016, and 2014 to understand how things have changed. We found:

- Physician compensation continues to emphasize volume more than value. Physician compensation comes mainly from traditional sources, and meaningful performance bonuses are the exception rather than the norm.

- In 2020, as in 2018, almost all physicians (97%) relied on FFS and/or salary for their compensation and 36% also drew compensation from value-based payments.

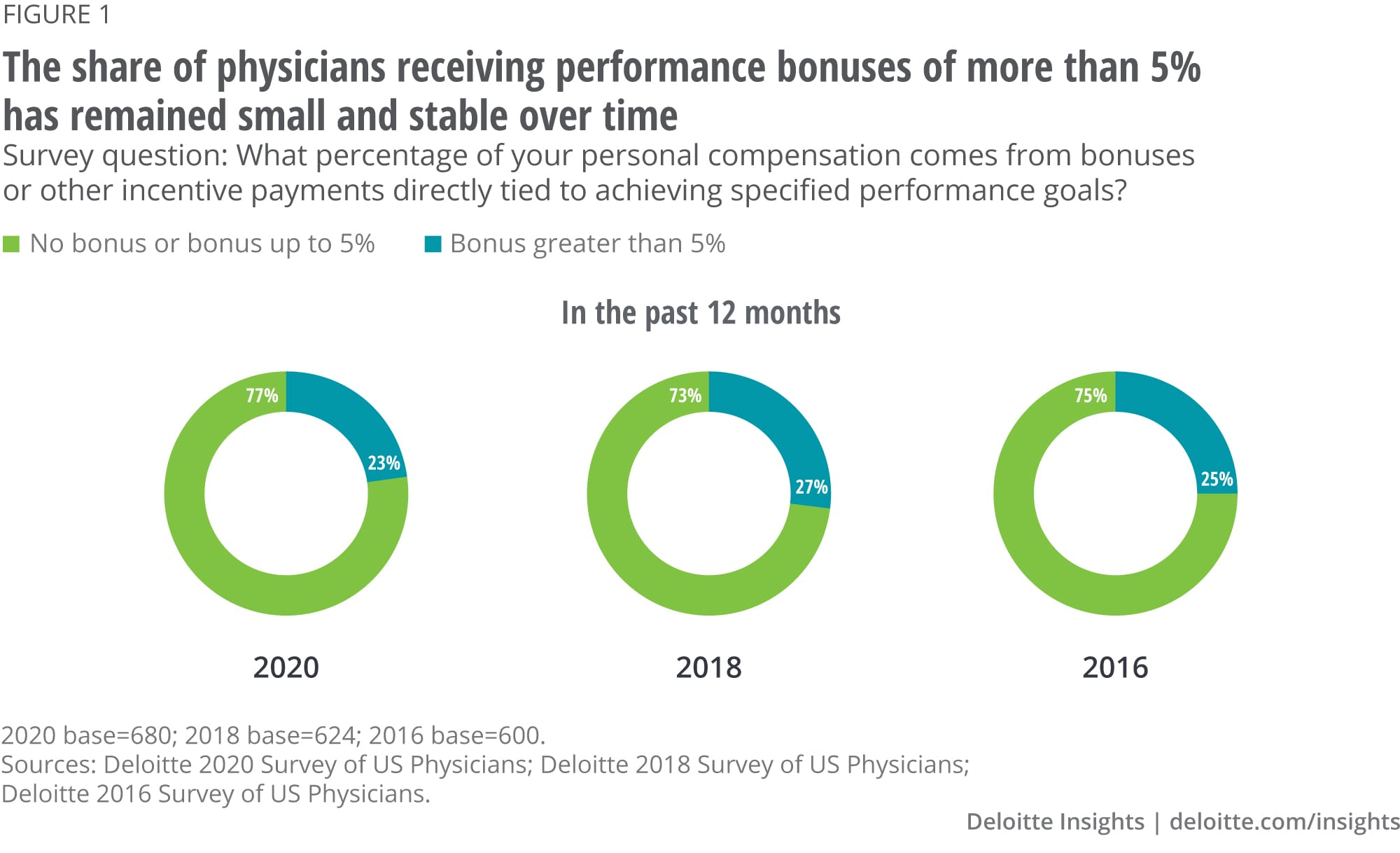

- The proportion of physicians (23%) who receive performance bonuses of more than 5% also hasn’t changed.

- Availability and use of data-driven tools to support physicians in practicing value-based care continue to lag:

- Only one in two (51%) physicians are aware of the costs of treatments they select.

- Almost half (48%) are comfortable discussing costs with patients.

- Just under half (46%) say they follow clinical pathways adopted at their organization.

- Existing care models do not support value-based care and many untapped opportunities remain for improving the quality and efficiency of care. For instance:

- Physicians estimate significant portions of their work today can be performed by nonphysicians (30%) in nontraditional settings (30%) and/or can be automated (18%).

We believe the time has come for the industry to move more decisively toward value. To accomplish this, organizations should implement three parallel initiatives:

- Reorient physician compensation from volume to value and hold physicians accountable for outcomes.

- Give physicians easy-to-use tools for decision-making and performance improvement.

- Build care management capabilities, such as multidisciplinary coordinated care teams, risk stratification, care navigation, and site-of-care optimization.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the financial security of many health systems and physicians as traditional revenue streams based on FFS plummeted. According to the Medical Group Management Association, in late April 2020, 97% of medical practices experienced a negative financial impact directly or indirectly related to COVID-19. This included a 60% decrease in patient volume and a 55% decrease in revenue, forcing many practices to furlough or lay off staff.1

Before the pandemic, most health systems approached value-based arrangements with caution. According to the analysis by the Catalyst for Payment Reform, although the percentage of dollars flowing through value-oriented methods in commercial health insurance has increased from 10.9% in 2012 to 53% in 2017, only a small share of total dollars (~5%) is at risk, and this share has not changed over time.2 We see parallels in the public sector: Seventy-one percent of 2019 Medicare Shared Savings Program participants were in upside-only arrangements.3 With most of providers’ revenue still tied to FFS, there has been little business need for organizations to reorient their care models and physician compensation around value.

In this article, we study the trends in the data from the Deloitte 2020 Survey of US Physicians against 2018, 2016, and 2014 to review progress over the past six years. We think this nationally representative data can inspire further discussions for organizations that consider transitioning to value-based care, with more significant shares of revenue at risk. We propose ideas on how they might engage and enable their physicians to practice value-based care.

Quick facts about the study

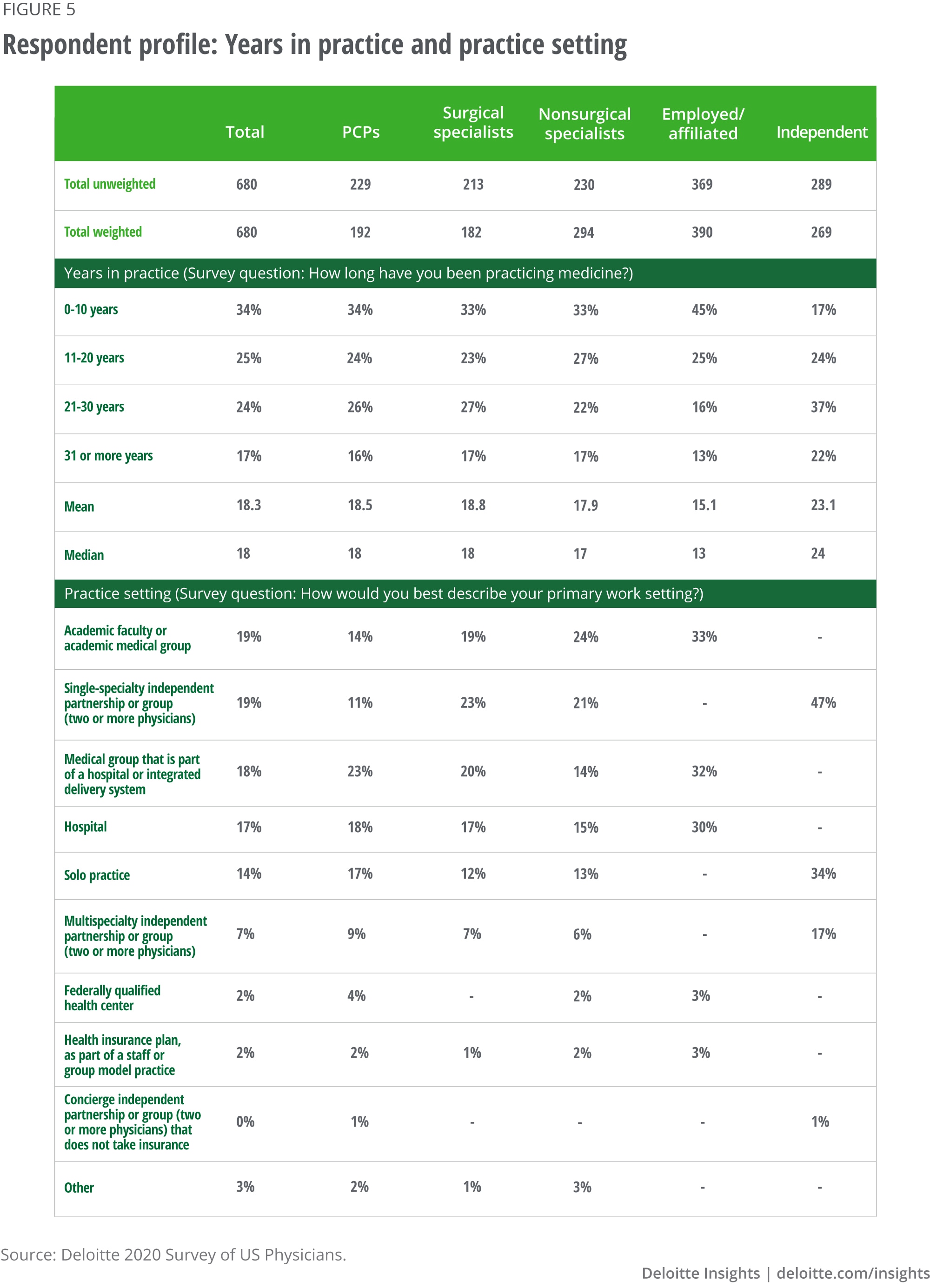

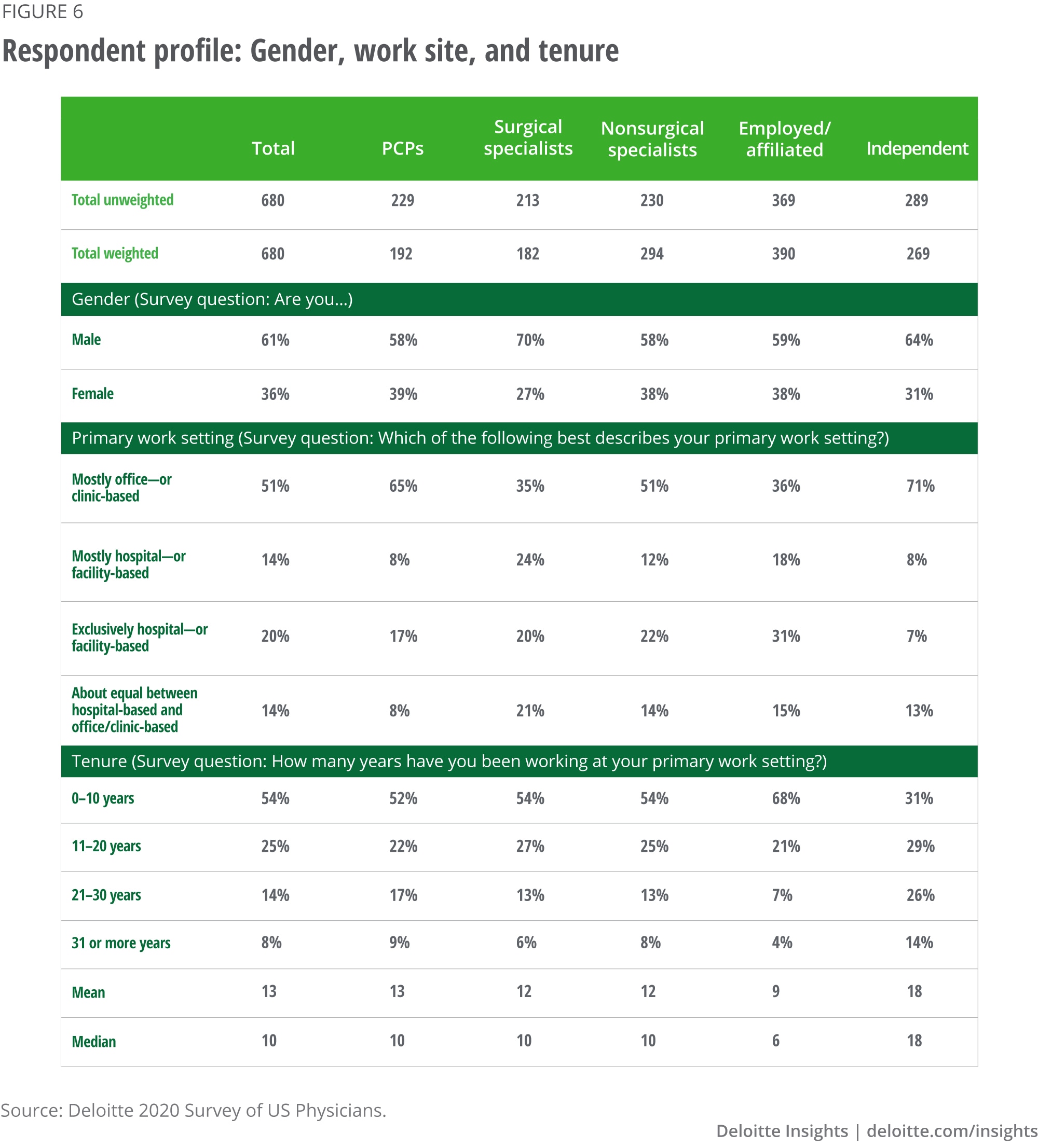

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions fielded its biennial survey of US physicians, performed since 2011, from January 15 to February 14, 2020. This survey of 680 physicians is nationally representative of US primary care and specialty physicians with respect to years in practice, gender, geography, practice type, and specialty. See the Appendix for detailed information on our sample.

For this article, we compared the responses from the 2020 survey to identical or similarly worded questions in previous surveys from 2018, 2016, and 2014.

Key findings

Physician compensation continues to emphasize volume more than value

Traditional sources of payment remain common in physician compensation

Over the years, we have asked physicians about payments that represent sources of their compensation. We put them in two broad categories, although it is possible to draw compensation from more than one source at once:

- Traditional sources of payment include salary and/or FFS.

- Value-based sources can be any of the following: bundled payments, shared savings, shared risk, procedural episode-based payment, or capitation.

This year, as in previous years, we do not see shifts in sources of payment compared to two years ago. Traditional sources (97%) continue to be the predominant way physicians are paid, whereas value-based payments (36%) remain less common sources of compensation.

Our client experience echoes these findings: Compensation models inherited from the 1990s remain common, such as work relative value units, number of admissions or shifts, revenue minus practice expenses, or percentage of collections or gross charges billed.

Performance-based bonuses continue to play a small role in physician compensation

Over multiple years of the survey, we asked physicians about the share of their compensation tied to specific performance goals. And even though we see some (nonsignificant year-over-year) fluctuations, the proportion of physicians who receive meaningful bonuses of more than 5%, has remained largely unchanged, about one in four (figure 1). In 2020, the majority (77%) either received small performance bonuses of up to 5% (39%) or were not eligible for bonuses altogether (39%).

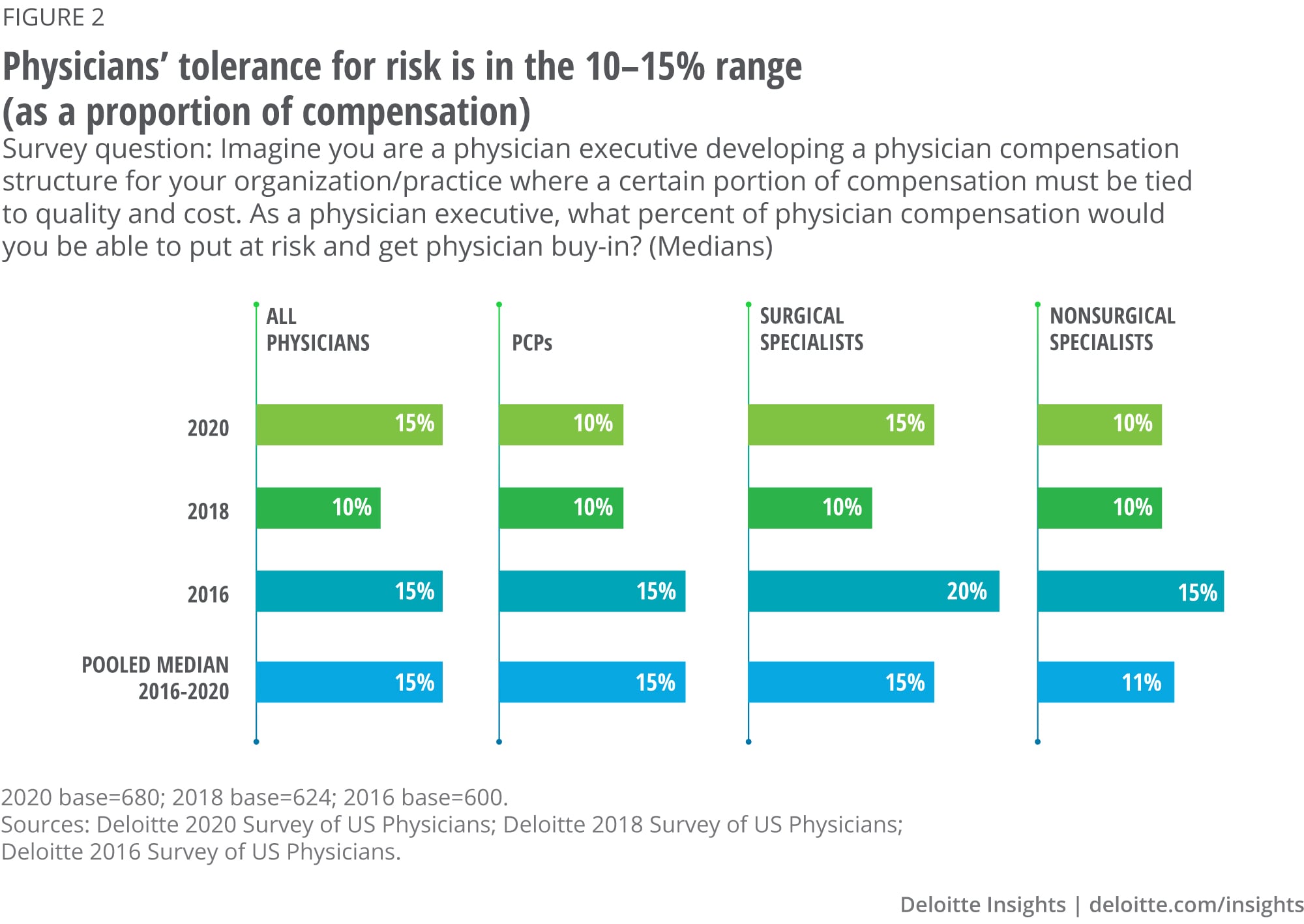

Physicians’ tolerance for risk is greater than their typical bonus—in the 10%–15% range.

At the same time, physicians have told us that they are willing to accept more risk than their typical bonus today: They would accept between 10% and 15% of total compensation tied to quality and cost. This tolerance for risk has remained stable over time and tends to be lower among nonsurgical specialists (figure 2).

Progress in providing data-driven tools to support physicians in practicing value-based care is slow

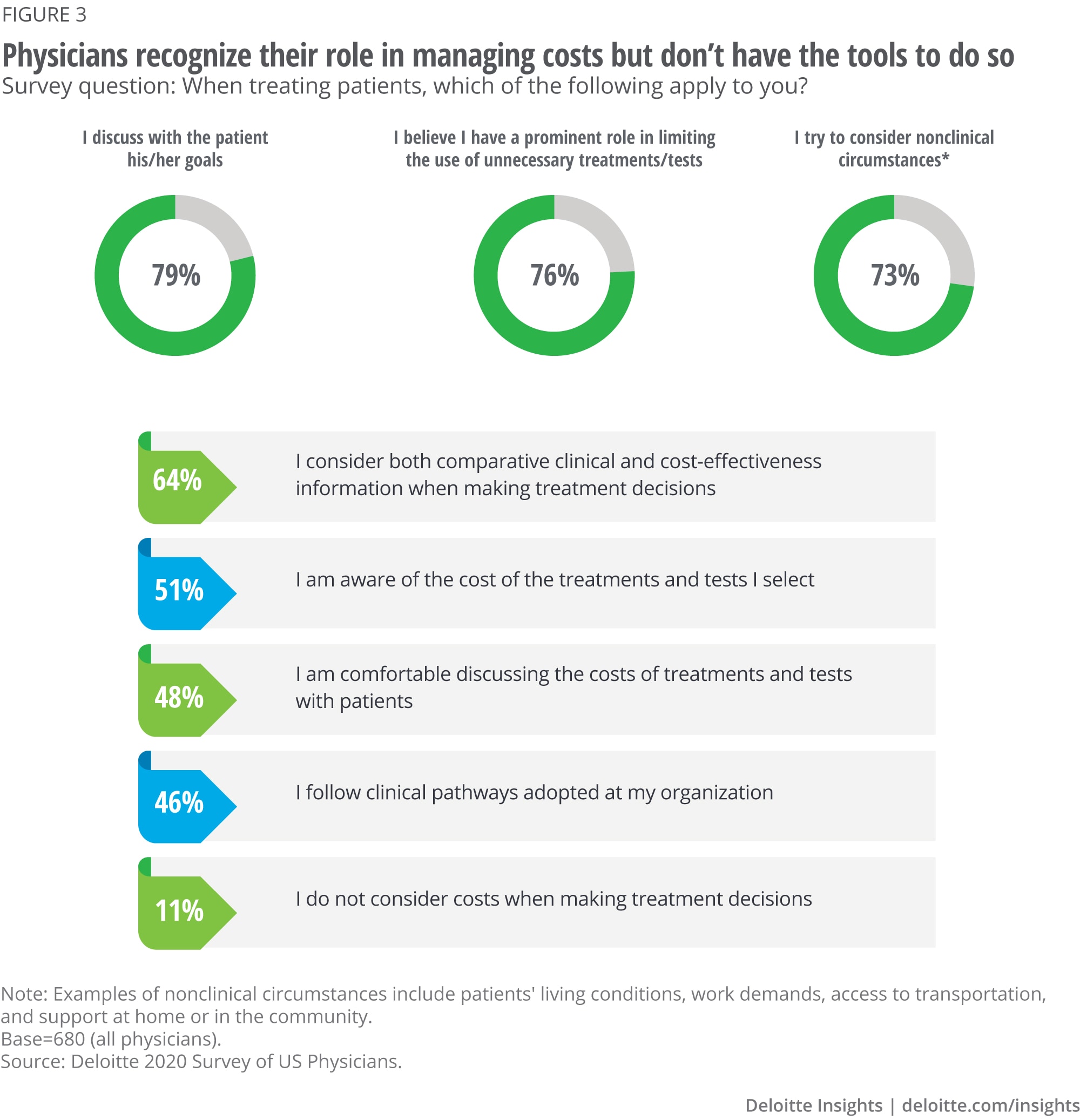

Progress is slow in equipping physicians with the tools and capabilities to support value-based care:4 Only 51% are aware of the costs and treatments they select, and 48% are comfortable discussing costs with patients (figure 3). These statistics haven’t increased from 2014. And even though 73% of physicians say they try to incorporate nonclinical considerations around social determinants of health (figure 3) into their decision-making, foundational information to help address social determinants is hard to come by. Fewer than half (46%) of our respondents have access to economic and community profile data of the patients their practice serves through either the electronic health record (EHR) (25%), a portal (12%), or paper or fax (10%).

One tool that we estimate is widely available doesn’t see much use. Designed to bring the evidence base to the practice and reduce variation in care, clinical pathways were available to 77% of physicians in 2016.5 Yet, four years later, less than half (46%) of our respondents say they follow clinical pathways adopted at their organization (figure 3). This suggests physicians remain concerned about relinquishing their independent clinical judgment and/or underappreciate the improvements in outcomes, quality, and the cost that can come from care standardization.

Today’s care models do not support value-based care

Physicians increasingly recognize their role in improving the affordability of care. We repeated a question we asked six years ago and saw a large increase in the proportion of physicians who say they have a prominent role in limiting the use of unnecessary treatments and tests: 76% in 2020 vs. 57% in 2014.

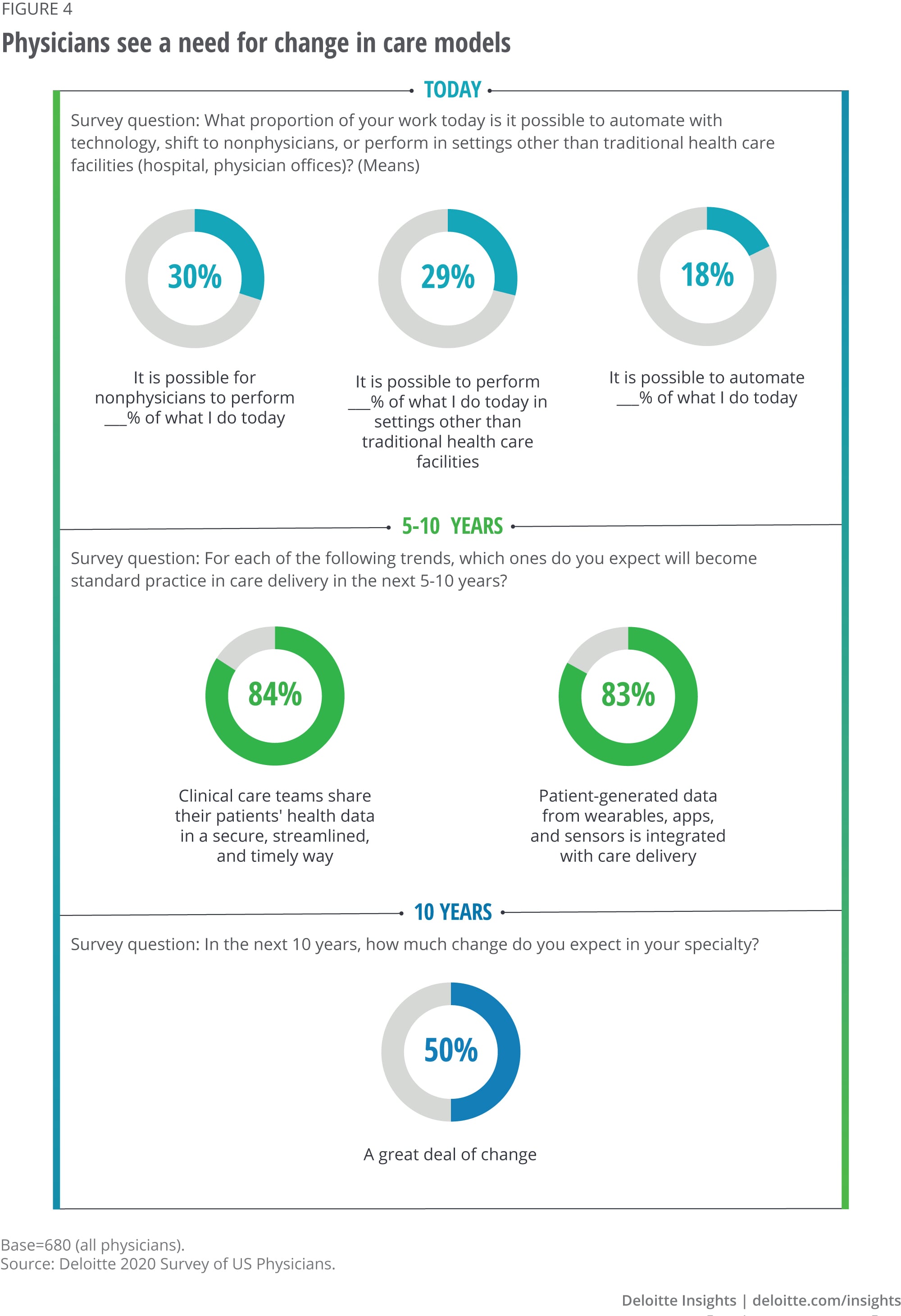

Physicians also recognize that today’s care models are not geared toward value. They see many untapped opportunities for improving quality and efficiency. They estimate that even today, sizable portions of their work can be performed by nonphysicians (30%) in nontraditional settings (30%)6 and/or can be automated (18%), creating opportunities for multidisciplinary care teams and clinicians to work at the top of their license. Other survey responses indicate that physicians see a possibility for considerable changes in care models in the future (figure 4). Physicians expect interoperability to be largely achieved in the next 5–10 years, opening possibilities for better care coordination and use of nontraditional data in patient care. One in two physicians expects a great deal of change in their specialty (50%) in the next 10 years, particularly primary care practitioners (61%).

Physicians’ views about knowledge and skill requirements going forward also reflect their expectations of changing care models. The top three issues they want medical education to address are:7

- Business and economics of medicine (65%)

- Prevention and sustaining well-being, such as nutrition or social determinants of health (59%)

- Development of teamwork skills (45%)

Between 2014 and 2020, there was a 19-percentage point increase in the proportion of physicians who say they have a prominent role in limiting the use of unnecessary treatments and tests

Our view is that a population health approach is essential for organizations to succeed in value-based care, and physicians’ work should be redesigned accordingly.

Today, most physicians care for individual patients, one at a time, focusing on the problem at hand. FFS rewards such episodic problem-oriented care and EHRs are an adequate tool. Under value-based care, physicians should adopt a population health mentality that represents a philosophical change in the care model and borrows many elements from the health insurers’ playbook. It calls for advanced care-management capabilities that enable a longitudinal and more holistic view of the patient through use of multidisciplinary care teams, risk stratification, care navigation and site of care optimization, understanding of care variation, and influencing patients’ behavior. Increasingly, the role of physicians is going to shift from that of an individual contributor to a team player. For more ideas on how physicians’ roles and care models might evolve, please see Deloitte’s publication Shaping the physician of the future.

Designing toward value-based care

An effective transition to value-based care cannot happen without getting physicians on board. We heard this sentiment in the Deloitte 2020 Survey of Chief Financial Executives of Health Systems and Health Plans conducted in June 2020. The physician network (in terms of composition, competition, and compensation) and financial viability are top business concerns (both at 47%) for health system CFOs. For more details, see Building resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: How health care CFOs are navigating with an eye on the future

To successfully transition to value-based care, organizations should implement three parallel initiatives:

- Reorient physician compensation from volume to value. Value-based care is in line with physicians’ intrinsic motivation to deliver the best care to their patients, as it drives improvements in quality, outcomes, and patient experience. Refocusing work from productivity to value can bring meaning to physicians’ work and reduce burnout. We recommend that any physician compensation redesign begin with agreeing on a set of guiding principles that align to the mission, strategy, and payer mix.

- Give physicians the tools for success. This will require a strong data-analytics engine with interoperable data, advanced enterprise data warehouse or cloud capabilities, and dynamic real-time reporting and analytics.

- Tools for decision-making: To support care for individual patients, relevant patient-specific data on outcomes and social determinants should be available to clinicians at the point of decision-making, not retroactively. Cost-related decision tools that use cost, resource use, and outcomes data should also be available to help physicians and/or their staff optimize referrals.

- Design for the end user: These tools should make it easy for physicians to choose the best option, using human-centered design and choice architecture principles.8

- Build care management capabilities to enable population health. On the analytics side, this requires risk stratification and patient segmentation (to understand their preferences and propensity to engage), analysis of care variation, and integration of data from multiple sources (clinical, nonclinical, wearables). And multidisciplinary teams, that could, in the future, comprise humans and technology, should provide care coordination and navigation, motivational coaching, nudging, and site-of-care optimization.

Value-based care is in line with physicians’ intrinsic motivation to deliver the best care to their patients.

Conclusions

As health care costs continue to rise, the payment system is moving to value-based care models in which quality and cost outcomes determine continued inclusion in insurers’ networks. This means that value-based care is no longer something organizations can choose to do as a pilot or an alternative to FFS. Rather, it is a critical part of any health care organization’s short- and long-term strategy to create top-line revenue and contain costs. Moreover, it is a path to transform the business model and position oneself for the future in which we expect the balance to shift from care and treatment to prevention and sustaining well-being.9

The industry should use this opportunity to elevate the physician’s role as the steward of physical, financial, and population health.

Appendix

Since 2011, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions has surveyed a nationally representative sample of US physicians on their attitudes and perceptions about the current market trends impacting medicine and the future state of the practice of medicine.

The aim of the survey is to understand physician adoption and perception of key market trends of interest to the health care, life sciences, and government sectors. In 2020, 680 US primary care and specialty physicians were asked questions about a range of topics: future of work, future of health, virtual health, digital transformation, and value-based care. For this article, we compared responses from the 2020 survey to identical or similarly worded questions on value-based care from the surveys of 2018, 2016, and 2014.

The national sample is representative of the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile with respect to years in practice, gender, geography, practice type, and specialty to reflect the national distribution of US physicians.

Data was collected between January 15 and February 14, 2020.

About the AMA

The AMA is the major association for US physicians and its Masterfile is a census of all US physicians (not just AMA members). The database contains records of more than 1.4 million US physicians and is based upon graduating medical school and specialty certification records. It is used for both state and federal credentialing, as well as for licensure purposes. This database is widely regarded as the gold standard for health policy work among primary care physicians and specialists, and is the source used by the federal government and academic researchers for survey studies among physicians. We selected a random sample of physician records with complete mailing information from the AMA Masterfile, and stratified it by physician specialty, to invite participation in a 20-minute online survey.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More for health care providers

-

How the virtual health landscape is shifting in a rapidly changing world Article4 years ago

-

Clinical leaders' top concerns about re-opening Article4 years ago

-

Hospital revenue trends Article5 years ago

-

Drug and inpatient spending lines are crossing Article5 years ago

-

Virtual health care Video