Drug and inpatient spending lines are crossing How might emerging therapies accelerate these trends?

15 minute read

08 February 2020

As spending shifts from inpatient settings to prescription drugs, stakeholders may need to consider how wider availability and greater adoption of targeted therapies could accelerate this trend—and what to do in response.

Executive summary

Today, the balance of spending is shifting from inpatient hospital (historically the costliest sector) to prescription drugs, according to an analysis of Medicare and commercial spending on inpatient medical services and prescription drugs. In the future, wider availability and greater adoption of targeted therapies (precision medicine), such as cell and gene therapies, will likely accelerate this trend, according to qualitative interviews with pharmacy benefit experts, providers of specialty care, and clinical researchers.

Learn more

Explore the Health care collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

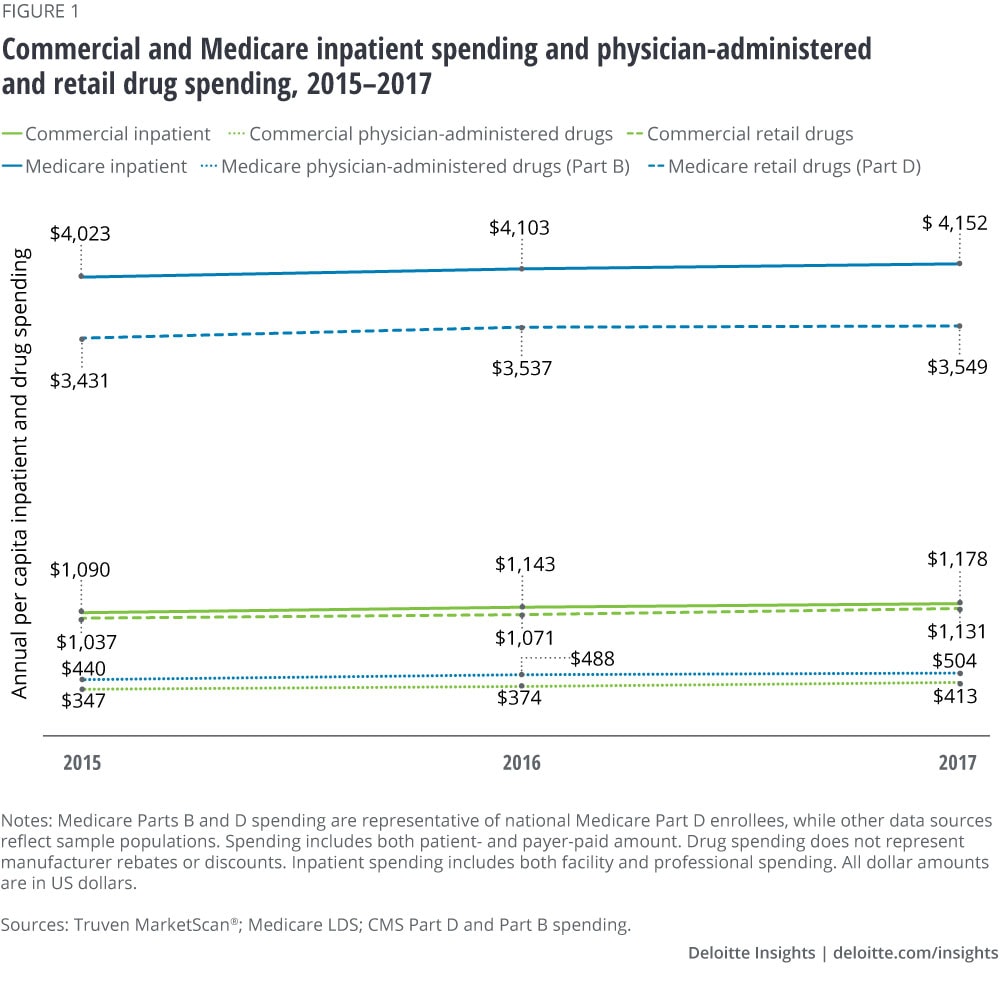

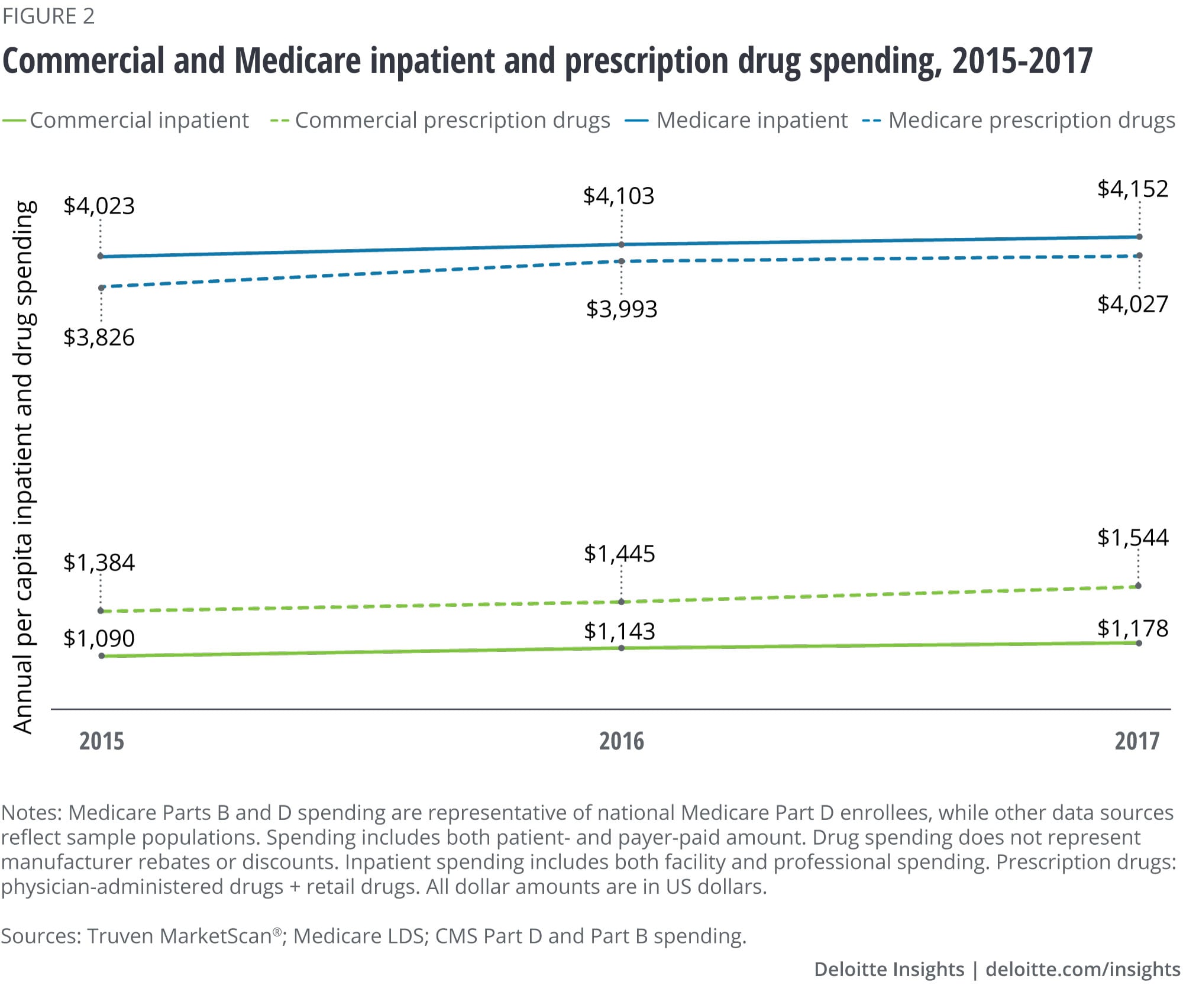

Quantitative analysis reveals that prescription drug spending (retail and physician-administered, including mail order and specialty) already surpasses inpatient spending in the commercial population. This is driven mostly by increases in spending in two areas: hormones and synthetic substances and immunosuppressants. The lines are close to intersecting in the Medicare population.

Discussions with experts centered on the intersection of this trend with the emergence of new curative and preventive, yet costly, treatments. One key takeaway from the interviews is that higher drug spending isn’t necessarily bad if it helps keep people out of the hospital and provides value to the system. Moreover, newer innovative treatments, such as cell and gene therapies, target a relatively small population, so they don’t make a major impact on total spending trends today. However, future therapies might expand to treat broader patient populations, potentially driving up spending, while technology could allow mass customization for precision medicine at a lower cost. This will likely drive spending in the future, but it’s unclear yet in which direction.

As we look toward the future of health, which Deloitte envisions will be very different by 2040, we anticipate that care will shift out of traditional settings and that prescription drug utilization will change from being only oral solids and biologics to include digital therapeutics, food as pharmacy, implants, and 3D-printed combination therapies. We also anticipate a greater mix of curative and preventative treatments instead of the current focus on maintenance and management of chronic conditions. In this future, as next generation emerging therapies become available and more affordable, we could see lower disease burden as people live longer, healthier lives.

Today, emerging therapies present a unique challenge to the health care system: How will we pay for these potentially curative therapies, especially as their indications expand? We expect payers to continue asking this question as they seek more information on the durability of these treatments and to continue demanding that care shift out of more expensive settings. And, as health care stakeholders prepare for tomorrow, we could see an acceleration of these trends.

Drug spending exceeds inpatient spending in some cases

The Office of the Actuary at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) projects that retail drug spending—drugs furnished by retail pharmacies as part of the drug benefit—will grow faster than other areas of spending over the next decade.1 Spending on physician-administered drugs—those administered by physicians or hospitals as part of the medical benefit—is growing even faster.2

Analysis of the three most recent years of data from IBM Truven MarketScan®, the Medicare Limited Data Set (LDS), and Medicare Part D and Part B finds that prescription drug spending (retail and physician-administered drugs) appears to have surpassed inpatient spending in the commercial population (see Appendix for methodology). Meanwhile in Medicare, the gap between inpatient spending and prescription drug spending is narrowing. (See figures 1 and 2.) Population growth and aging, the number of prescriptions per person, general inflation, drug prices, and the introduction of high-cost novel drugs are all contributing to this trend. The drug spending analyzed here does not account for manufacturer rebates or discounts. Recent estimates suggest that gross-to-net reductions paid by drug manufacturers, most of which come in the form of rebates, equaled US$166 billion in 2018.3

The hormones and synthetic substances therapeutic area (TA)—drugs that manage conditions such as diabetes and asthma—make up the highest proportion of prescription drug spending in both the commercial (21 percent) and Medicare (17 percent) populations. Beyond that, we see considerable differences between the two populations. In the commercial population, nearly half of total retail drug spending is driven by only three therapy areas: hormones and synthetic substances, immunosuppressants (systematic immunosuppressants indicated for inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, etc.), and central nervous system (CNS, drugs indicated for depression, Alzheimer’s disease, pain management, etc.). (See figure 3.)

In the commercial population, spending on immunosuppressants as a share of the total grew fastest among all therapeutic areas over the three years, from approximately 10 percent of drug spending in 2015 to 16 percent of drug spending in 2017. Greater understanding of how inflammation impacts diseases and organs coupled with an explosion of available therapies could help explain the spending growth in this area. Meanwhile, spending on cardiovascular drugs declined as a share of the total, from 9 percent in 2015 to 6 percent in 2017.

In the Medicare population, the share of cardiovascular drugs declined from 12 percent in 2015 to 9 percent in 2017. The entrance of generics into this space and rebates for newer, but not clinically innovative, drugs could be the drivers of this decline. Finally, oncology drug spending grew from 6 percent in 2015 to 8 percent in 2017 in Medicare. There are likely several drivers behind this, but a few could be the aging population, availability of higher priced drugs and greater penetration of those drugs, and the introduction of combination therapies in this space.

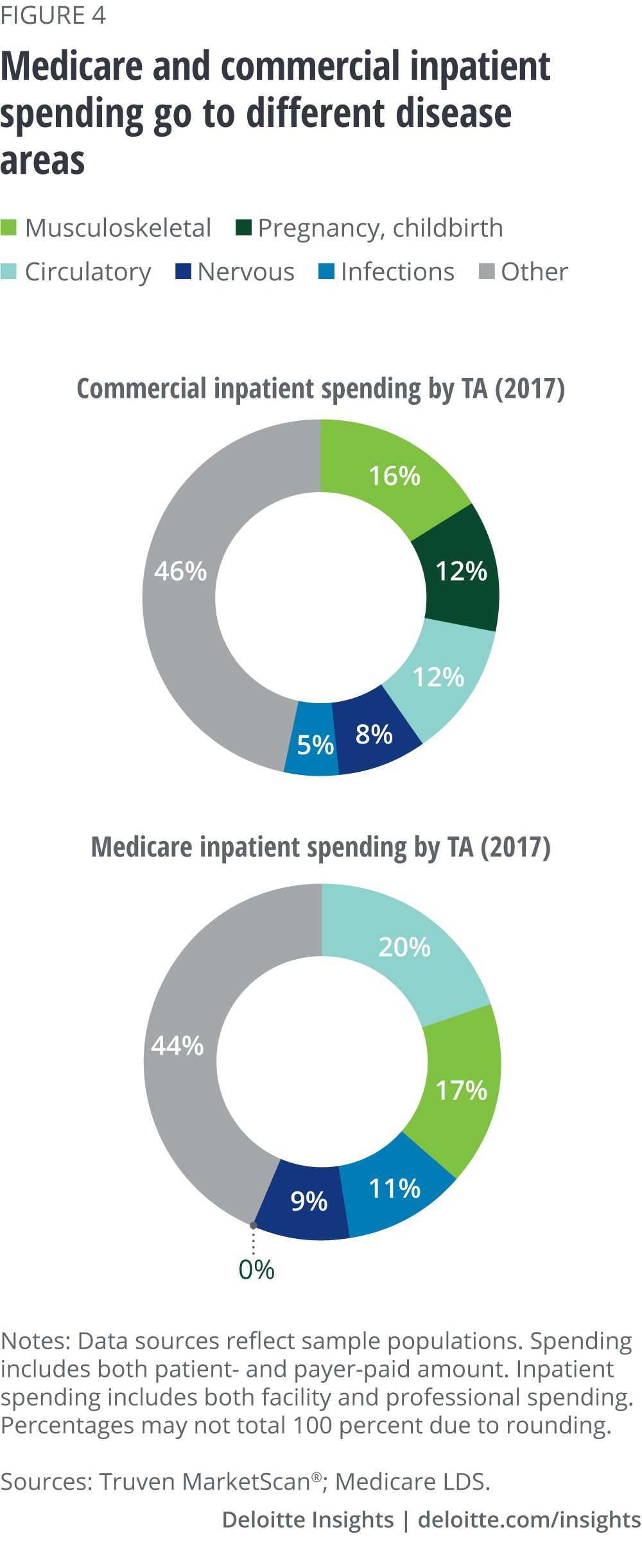

Like drug spending, inpatient spending also differs in Medicare and commercial populations. For example, spending on circulatory diseases accounts for 20 percent of the total in Medicare and only 12 percent in commercial. Musculoskeletal accounts for approximately the same share (16–17 percent) in both commercial and Medicare populations. (See figure 4.) While drug spending saw significant shifts over this period, inpatient spending remained relatively stable—no one disease area saw significant growth or decline.

Stakeholders expect new therapies to be major drivers of future spending trends

To get some insight into what the future will hold, we asked experts at pharmacy benefit managers, providers of specialty care, and clinical researchers to help us look into the future. These experts focused on the acceleration of adoption of emerging therapies (e.g., cell therapy, gene therapy—see sidebar, "Defining next generation therapies," for definitions) as one of the major trends that might take us off conventional forecasts.

Defining next generation therapies

Cell therapy is the transfer of intact, live cells into a patient to help mitigate or cure a disease. Cellular therapy products include cellular immunotherapies, cancer vaccines, and other types of both autologous (from the patient) and allogeneic (from a donor) cells for certain therapeutic indications, including hematopoietic stem cells and adult and embryonic stem cells.

Gene therapy is a technique that modifies a person’s genes to treat or cure disease. Gene therapies can work by replacing a disease-causing gene with a healthy copy, inactivating a disease-causing gene that is not functioning properly, or introducing a new/modified gene into the body to help treat a disease. The transferred genetic material changes how protein is produced by the cell and is delivered into the cell by a vector, typically a virus. Gene therapy is provided through an IV injection. Gene therapies can be developed using gene-editing technologies such as clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR). Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, a form of cancer treatment that uses a patient’s own genetically modified immune cells to fight disease, is the first type of FDA-approved gene therapy.

While today there are few approved treatments on the market, many more are in development. For example, there are only two approved CAR-T therapies on the market,4 but projections expect approximately 350,000 patients to have been treated with 30 to 60 cell and gene therapy products by 2030.5 Nearly half of the products are expected to target B-cell (CD-19) lymphomas and leukemias.6 So far, these products have come with major challenges to the US health care system while also presenting optimistic results for the future. For one, they often offer the promise of a cure in patients who qualify for the treatments. On the other hand, they usually come onto the market with high prices. One recently approved gene therapy costs US$2 million per patient.7 And, they are complex therapies to administer; today these treatments are administered primarily in hospital settings, which drives additional costs on top of the drug costs.

Payers are looking down the road

Many payers desire more certainty around the pipeline, durability, and speed of future therapies, and whether the site of care will shift in the future.

Many payers say they are not worried about ultra orphan indications, but applications for cell and gene therapies are expected to expand

The budgetary impact of emerging therapies today for ultra orphan indications (even with US$2 million treatments), while not insignificant, is mostly manageable when spread across a broad population. This is mainly because they affect small populations. Experts said that most commercial payers are setting up arrangements with providers to pay for these therapies today. For example, Cigna recently announced its Embarc Benefit Protection program, which will operate under its pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts. The program will charge plans a monthly, per-member, per-month fee to enroll, requiring physicians to submit prior authorization and charging patients no out-of-pocket fees in exchange for access to two high-cost gene therapies.8 Another model is using stop-loss insurance, as suggested by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Center for Biomedical Innovation (CBI) through its NEW Drug Development ParadIGmS (NEWDIGS) Initiative.9 This group has also examined other models such as the Orphan Reinsurer and Benefit Manager (ORBM), which are entities that would work to give “payers with predictable costs; providers with appropriate reimbursement; developers with market access; and patients with a single point of contact.”10

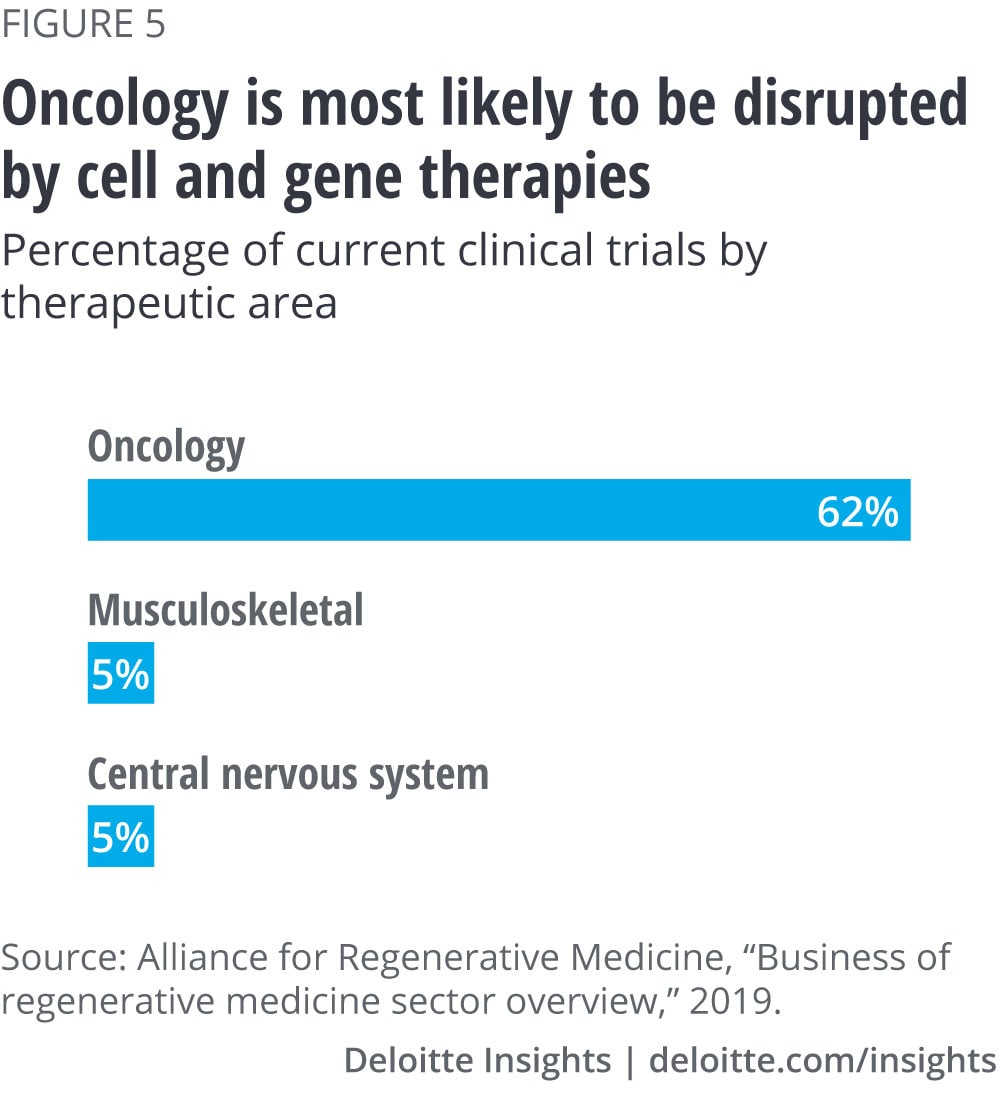

Payers are watching what’s coming down the pipeline. One expert we interviewed predicted that 50 percent of new spending will come from oncology and 50 percent from everything else (Alzheimer’s, heart failure, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis). Researchers have found that of the 1,052 clinical trials currently underway, oncology trials make up 62 percent of them.11 (See figure 5.) If there were a therapy that tackled Parkinson’s disease, payers would be concerned about the number of patients who can be affected. To limit costs in the future, some payers may also turn to imposing restrictions such as step therapy, requiring patients to take cheaper alternatives/cheaper standard of care prior to gaining access to the new, expensive drug.

Uncertainty around what successful therapies will target and whether site of care will shift

While many payers are concerned about what new therapies will emerge in the future, many of the experts we interviewed said they are unclear what the therapies will successfully target. Many brought up Alzheimer’s disease as an area they are tracking closely. There have been many recent failures in this therapeutic area, but the potential is great at the same time. Today nearly 6 million people have Alzheimer’s, and it is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States.12 Another important trend to note is that emerging therapies for diseases that lack good therapies today are not likely to have significant competition, which otherwise would drive some of the cost down.

We also asked the interviewees to weigh in on whether they think that site of care for these therapies will shift in the future. Today, many of these therapies are administered in complex treatment centers and require significant monitoring of the patient for complications postadministration. But some said they believe these treatment centers could follow the same pathway as infusion clinics. They note that infusions were primarily done in the inpatient setting at the outset. But once the models were perfected, and clinicians gained more control over complications, infusion began to move into the outpatient setting. More recently, home infusion has been an option for many patients. As treatment centers for cell and gene therapy gain more experience—and more economies of scale—they may move into less complex settings of care, too. One expert also cited regulatory barriers around where and how CAR-T is administered as a significant issue today.

Experts are uncertain where net costs for emerging therapies will land in the future

Interviewees predict that cell and gene therapy applications could expand to larger populations, but uptake by payers depends on several factors, some of which are still uncertain.

Payers should consider the costs associated with these therapies as they’re applied to larger populations

When it comes to predicting the costs of future therapies, there is no one-size-fits-all answer, according to the experts we spoke with. The size of the population and typical disease trajectory are two factors that were frequently discussed. Many of the experts we spoke with believe that commercial payers might bear the brunt of the costs for these treatments, without receiving much benefit in the long term. For example, if there were a therapy to prevent or treat Alzheimer’s before a patient develops significant symptoms and that therapy was administered when a patient is in their 40s, it is likely to hit employers and commercial health plans. However, many of the costs for Alzheimer’s hit in later years, most often when a patient is enrolled in Medicare. In this scenario, commercial payers would not see much budget savings down the road. Some experts did note, however, that this could save significant Medicaid dollars in the long run, as long-term services and supports for patients with Alzheimer’s are mostly funded by Medicaid.

Speed and durability are key for many payers

Payers want to be able to recoup costs quickly. Payers also want more certainty around the durability of these treatments.

The experts we spoke with acknowledged that cost savings may come downstream from the initial treatment. But this can be an issue in the commercial market, where the average tenure of employees—and thus the average time they stay on an employer’s insurance—is around four years today.13 In addition to concerns about long-term cost savings, many experts said that a key concern for payers is that the treatments do what they were found to do in clinical trials in the long term as well.

The products are expensive—and so are the ancillary costs

Finally, many of the experts said that in addition to the cost of the actual products, they are tracking the large costs of the facilities and professionals needed to administer these therapies. Treatment centers need adequate, well-trained staff—and there aren’t many right now. As of February 2019, there were only 160 locations certified to provide CAR-T therapy.14 Payers want to ensure their patients are going to the right place to get the right diagnostics and procedures. Health systems that have these treatment centers could see large increases initially in both products and patients.

But, down the road, payers will likely push for care to shift out of these settings. Indeed, according to Deloitte’s 2019 Health Care CEO Perspectives Study, CEOs say that one of the most important drivers of change in the next 10 years is the shift in care settings. As this trend accelerates, it will likely impact all services, including provision of curative therapies.

Implications

As more curative or preventive therapies emerge, health care stakeholders should weigh the great potential they have to tackle disease burden and, at the same time, consider the significant costs that are associated with these treatments.

Payers—health plans, employers, Medicare, and Medicaid

- Continue driving toward value by shifting care out of more expensive settings and identifying emerging therapies that are shown to be effective.

- Identify the best outcome measures to base decisions in efficacy of treatments.

- Explore alternative payment models including value-based contracting.

- Push for comparative effectiveness studies that compare drug therapies with alternatives, especially as digital therapeutics and other solutions come to market.

Health systems and centers of excellence

- Work with payers to develop appropriate treatment guidelines and to understand the costs of both the products and the facilities and professionals associated with currently approved cell and gene therapies.

- Identify ways to improve outcomes and be paid for outcomes as providers increasingly take on risk. This should include weighing the tradeoffs between being viewed as an innovative organization and whether they're able to provide cost-effective services.

How will the future of health affect inpatient and drug spending?

Today, emerging therapies present a unique challenge to the health care system: How will we pay for these potentially curative therapies, especially as their indications expand? We expect payers to continue asking this question as they seek more information on the durability of these treatments and to continue demanding that care shifts out of more expensive settings. And, as health care stakeholders prepare for tomorrow, these trends could accelerate.

Indeed, Deloitte envisions a very different health system by 2040. Data-sharing and interoperability, consumer engagement and demand, access to care, and scientific breakthroughs will likely drive many of these changes. As a result, we anticipate much less care being provided in traditional settings, and possibly even lower use of traditional medications over the long term. We expect our definition of health to broaden to include other aspects of well-being, and economic activity in health to focus on keeping people from getting sick in the first place. We expect data-sharing to drive both insights and proactive, real-time interventions. Targeted therapies, such as the ones discussed in this report, may become available and affordable broadly. Scientific breakthroughs could exponentially increase, leading to lower disease burden in the long run.

Appendix: Quantitative analysis methodology

Data sources

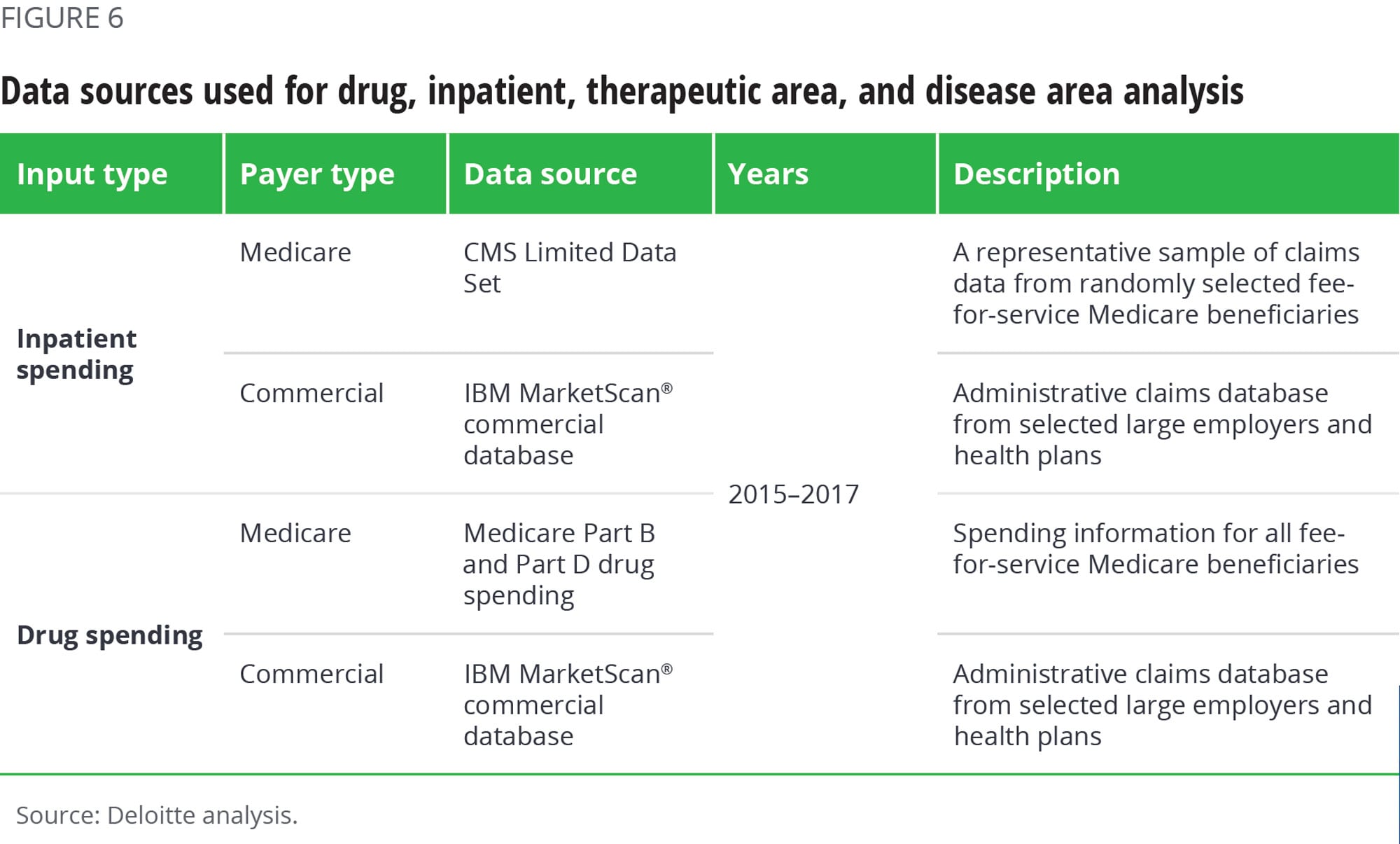

The quantitative analysis included data from the sources shown in figure 6.

Notes

- Spending includes the patient-paid and payer-paid amounts

- Drug spending does not include manufacturer rebates or discounts

- Inpatient spending includes facility and professional spending

Inpatient spending

ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes from the Medicare LDS and IBM MarketScan® commercial claims data were mapped to their respective diagnosis-related groups (MS-DRGs), which were in turn mapped to their respective major diagnostic categories (MDCs).

Drug spending

National Drug Codes (NDC) of drugs from the IBM MarketScan® commercial and names of the drugs from CMS spending claims data were mapped to their respective therapeutic class based on the American Hospital Formulary Service Classification Compilation (AHFSCC), which in turn were mapped to their respective therapeutic groups.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More on health care

-

Health care Collection

-

The future of health Collection

-

Digital health technology Article5 years ago

-

The health plan of tomorrow Article5 years ago

-

How physician networks can help bring down health care costs Article6 years ago