Navigating disruption

Five trends influencing tomorrow’s manufacturing industry

Brian Umbenhauer

Ben Dollar

Joe Zale

Heather Ashton

Introduction

For manufacturing leaders, the 21st century has brought with it an operating landscape that mixes longstanding patterns with new factors that are disrupting the industry. Many manufacturing companies that have not evolved are out of business, while digital-native companies are making a range of products from cars to phones to running digital marketplaces. At the start of the 2020s, it seems the only constant is an intensified pace of disruption and a call for manufacturers to recalibrate strategies and operations to prevail.

Learn more

Delve further into the five disruptive factors

Visit the Industrial products collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Deloitte has identified—through leadership discussions and analysis of primary and secondary sources—five factors that are expected to have an impact on manufacturers in the next 10 years (figure 1). Each varies in the time horizon of its potential impact, the scale of disruption it could deliver, and the level of preparedness manufacturers have for its expected impact. Nonetheless, all five could redefine how manufacturing will possibly look by 2030. This article describes these factors and suggests some of the primary ways in which they could alter where, when, and how manufacturers deliver value to customers and other stakeholders.

Specifically, manufacturing leaders will likely need to understand the following to differentiate themselves:

- The new properties of economic cycles and where manufacturers could create the most resilience to weather future market changes.

- The impact of different trade and tariff scenarios and the likelihood that manufacturers will begin to shift their operational models.

- The pace of disruption that digitization brings, and the investments manufacturers can make to best position themselves to succeed.

- The level of preparedness for the workforce changes brought about by the changing nature of work, the workplace, and the advancement of technologies.

- The primary factors that can advance electrification adoption in manufacturing and where manufacturers should focus their efforts in the near-term.

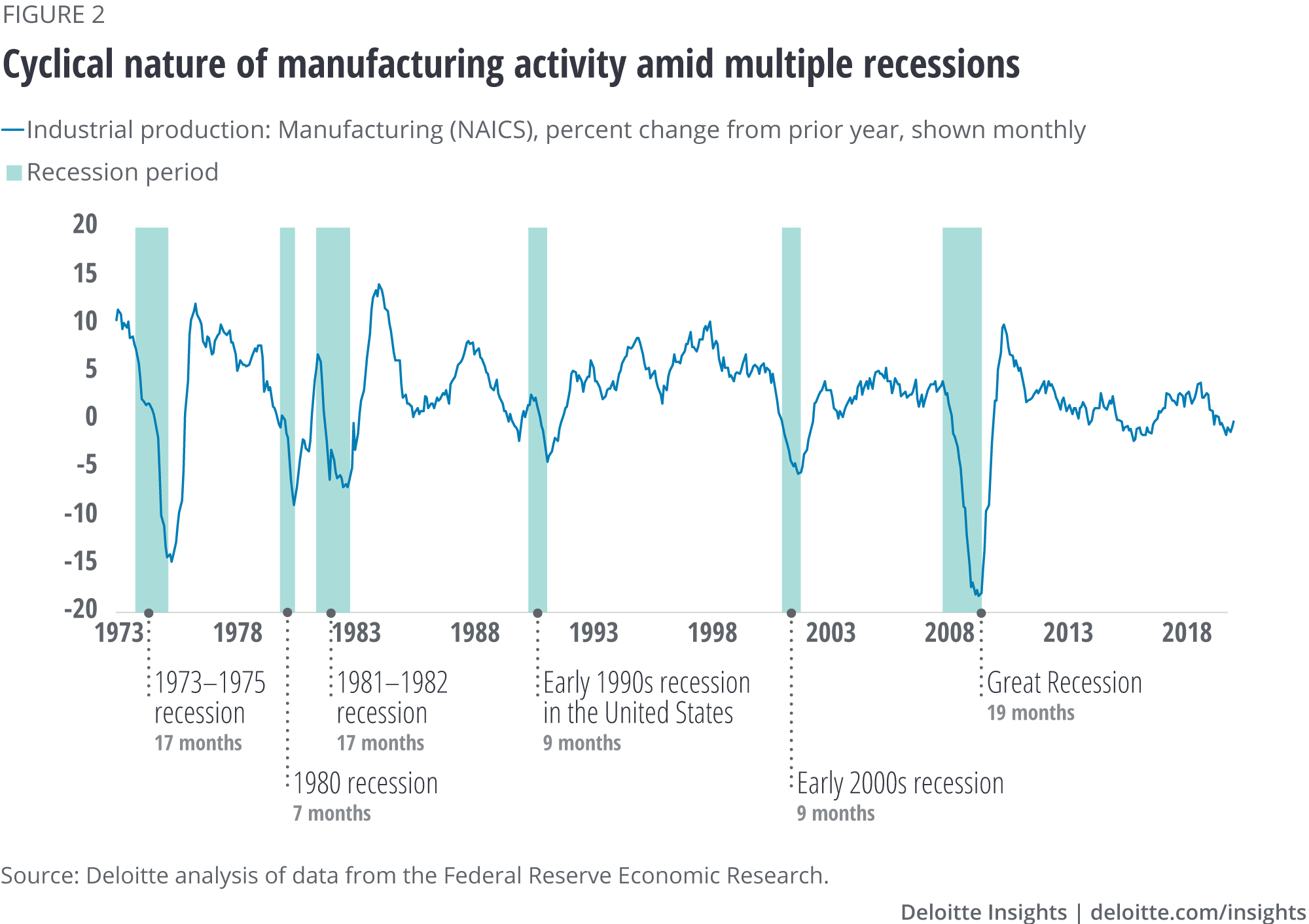

Building resilience in the face of changing economic cycles

Since World War II, the US economy has been through 11 recession periods, i.e., a recession every 6.1 years, each lasting about 12 months (figure 2).1 During the last two decades, the economy has already been through two recorded downturns, each of which impacted industrial production activity. An interesting aspect, however, is that the movement of these indicators has been volatile even during periods of overall US economic stability. This unpredictability likely suggests that some of the traditional barometers for manufacturing health may not reflect the new dynamics of today’s economy.

So, what are the new rules of play for manufacturers amidst economic cycles that may no longer resemble past history? The rise of advanced manufacturing technologies appears to be redefining traditional methods for measuring production, inventory, and other traditional performance metrics. Imagine a manufacturing environment where the purchasing managers’ index (PMI), which measures five key areas (new orders, inventory levels, production, supplier deliveries, and employment), no longer accurately tells how the manufacturing economy is performing. Today, six consecutive months of PMI contraction mean a recession. However, improved connectedness and analytics ability in the supply chain could change inventory levels; the increase in automation could alter how labor productivity is measured; and just-in-time manufacturing could change the cadence of supplier deliveries. The PMI could, therefore, become obsolete as an indicator of manufacturing economic performance.

With transformations like digitization helping manufacturers build resilience throughout their operations to weather downturns, the next recession could look distinctly different from the past few recessions. However, there are still some measures manufacturers can take now to build resilience even as they move through the transformation that digitization brings. Deloitte performed a statistical analysis that identified some telling patterns from the past two recessions that could provide valuable insights into how some manufacturers fared better than others. Our companion report Did someone say recession? How manufacturers can create resilience during downturns provides a deeper look at our statistical analysis and outcomes. In particular, two distinct areas emerged.

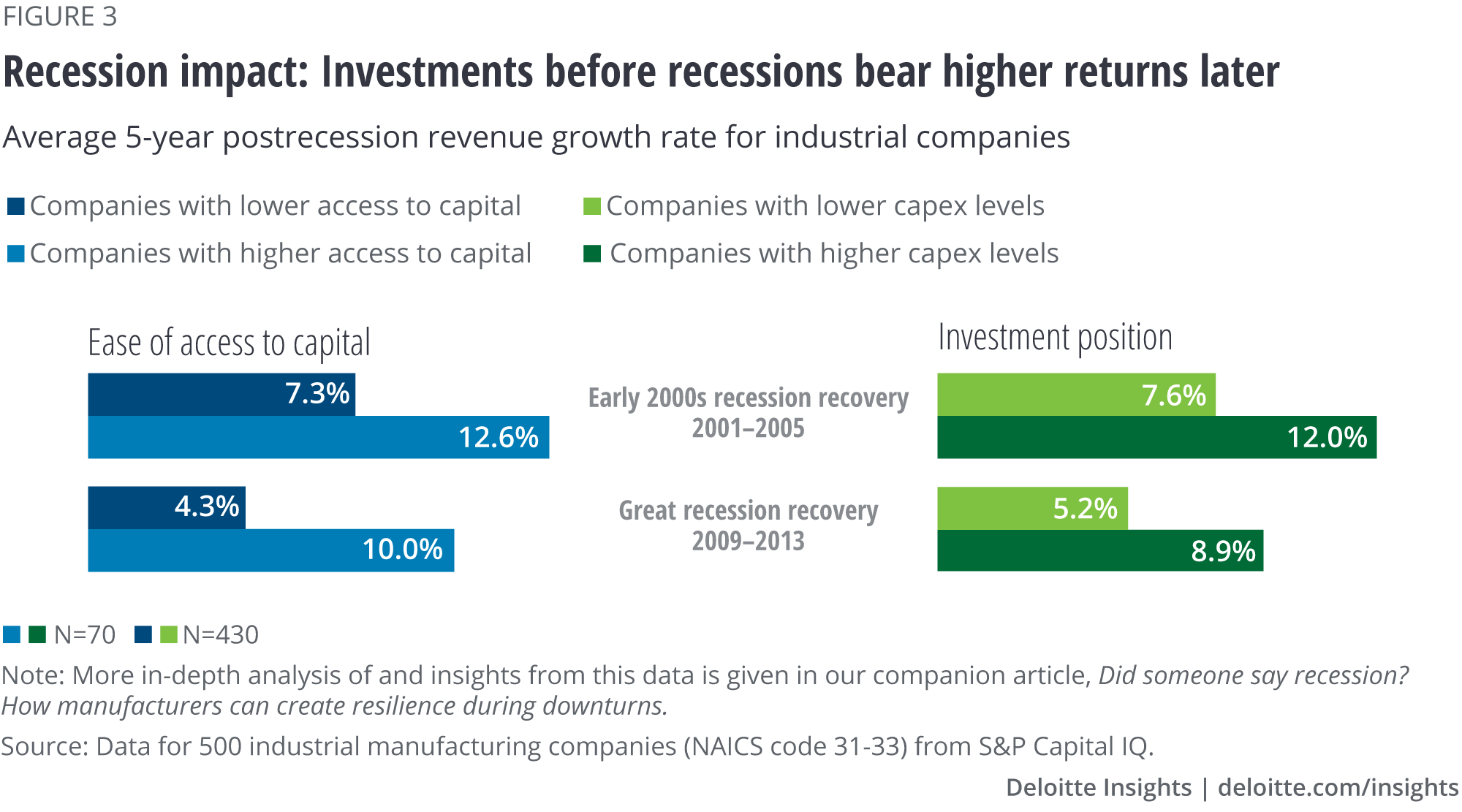

Liquidity and cash position. This is typically the most important measure to identify recession-resilient manufacturers. Manufacturers with easier access to capital and relatively lower debts were able to not only navigate through the recession better, but they also posted higher revenue growth during the recovery periods. Not just that, manufacturers with higher interest coverage ratios were able to generate capital when they needed it to invest back into operations.

Investment position. When heading into a slowdown or a possible recession, a basic instinct is often to dial down capital investments and wait for the onset of the recovery period. However, those industrial manufacturers that invested more during the period leading to a recession actually posted much better results. Ahead of the 2000–2001 recession, investment-resilient manufacturers invested US$15.1 for every US$100 in revenue, compared to an average of only US$4.7 per US$100 for other companies. Similarly, leading up to the recession of 2008–2009, the same group invested US$14.8 for every US$100 in revenue, compared to just US$3.4 per US$100 by other manufacturers. As a result of these capital investments in technology and assets, the resilient manufacturers observed much higher revenue growth during the recovery phases (figure 3).

Take action from these insights

- Recessions are unpredictable, both in terms of when they begin and their impact. To protect themselves, manufacturers should start preparing now rather than later.

- Assess liquidity, as well as cash position, to determine if there is adequate access to capital now.

- Determine potential capital investments that would build resilience in the current environment.

- Digitization of core processes and operations is an option worth considering.

- Measure technology and the capital asset investment/revenue ratio to compare with the resilient manufacturers’ performance in our analysis.

Trade shifts … and a turn toward regionalization

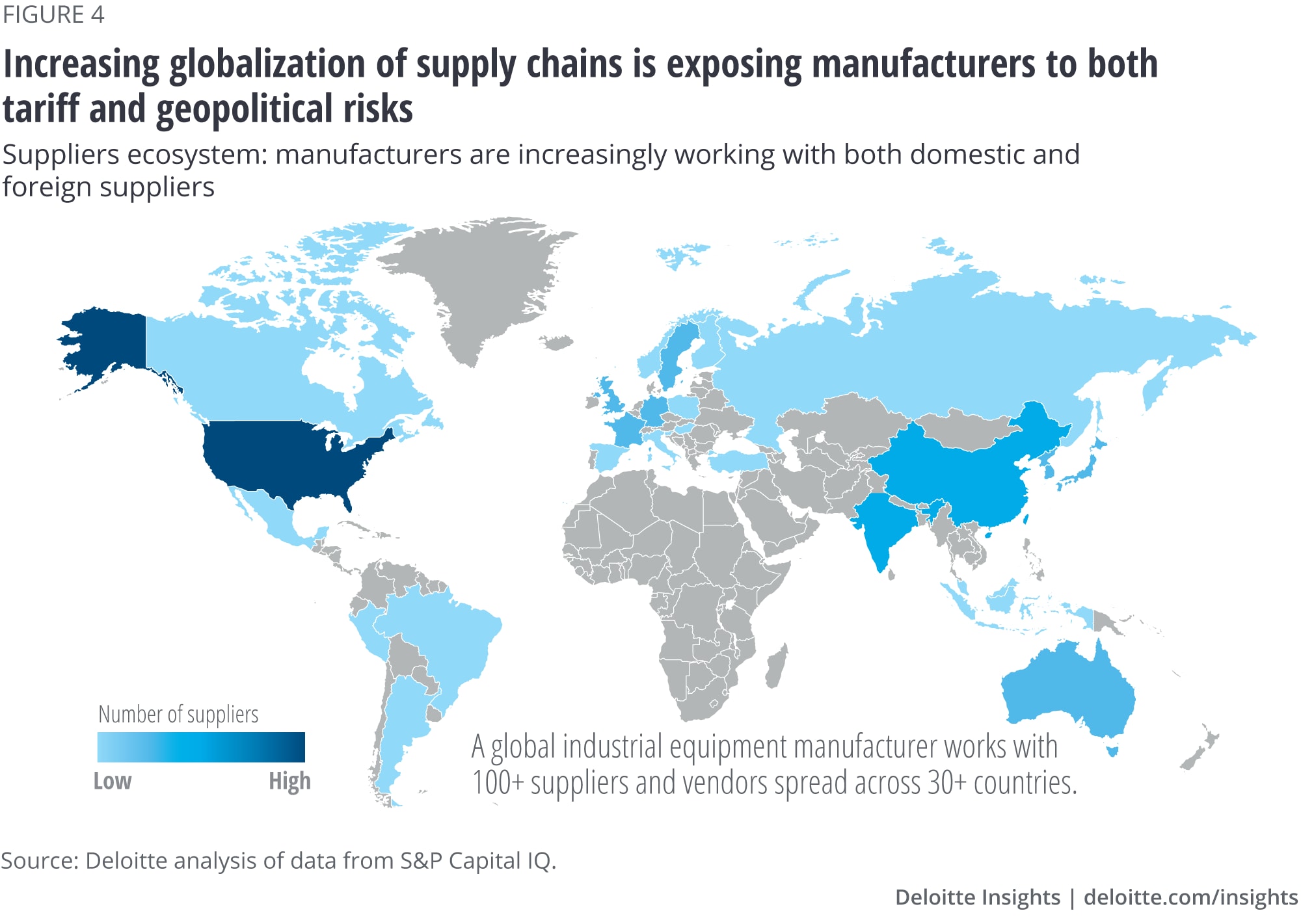

Globalization of the manufacturing ecosystem has transformed industrial supply chains into complex global networks. For example, in 2019 alone, US industrial manufacturing output was US$ 2,586 billion and the United States imported US$ 1,045 billion of industrial products and components.2 As such, many industrial products (machinery, vehicles, aircraft, etc.) reflect an intricate tapestry of origin (figure 4). So, what is a truly “American-made” car or airplane? Is it a product made of parts from all over the world, but assembled in the United States? Is it a product where a majority of the dollar value of content comes from the United States? Is it a product for which a US-listed company owns the manufacturing, or that is being built by an Asian company in Ohio, Kentucky, or Indiana? Today’s lines are clearly blurring about finished product origin, but they remain firm in country-specific trade rules and import/export compliance (figure 4).

The ongoing complexities in trade relationships between the United States and many of its global trading partners have put a strain on many industrial manufacturing companies’ operational and financial performance. The US-China Agreement, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (commonly known as the USMCA), and the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (commonly known as TTIP) between the United States and the European Union all have the potential to redraw traditional trade balances. For industrial manufacturers, a global accord landscape like this could affect everything from profit margins to production decisions.

In fact, many of Deloitte’s industrial manufacturing leaders identified the significant impact of ongoing trade restrictions and tensions as increasing costs and margin pressure.3 More significantly, most manufacturers could be minimally prepared to handle a long period of trade volatility.4 Despite the announcements of bilateral trade agreements in the past 18 months, all indicators suggest that this restructuring of the new global trade landscape may well last for the foreseeable future. How should manufacturers navigate trade dynamism and how can they better prepare to weather the ongoing uncertainty in the future of trade?

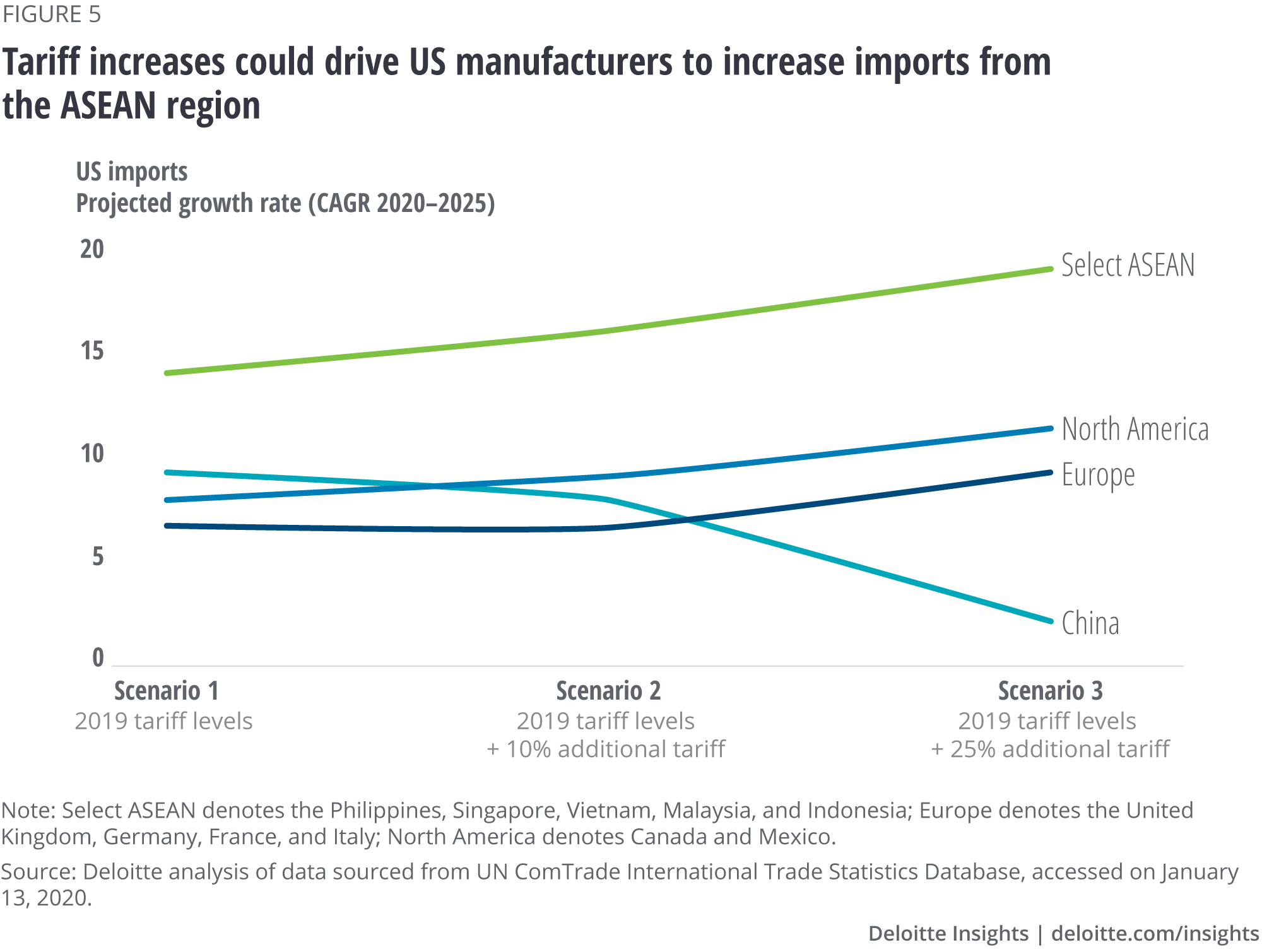

In our article, Changing global trade policies: How manufacturers can navigate the dynamic trade climate?, we list some of our key insights related to the ongoing trade dynamics. We’ve also developed a proprietary trade-tariff model for manufacturers that we’ve used to illustrate the potential consequences of changing tariffs and duties on a typical US manufacturing company (figures 5 and 6).

Among the high-level findings are the following:

- Deloitte analysis reveals gross margins could fall by almost 17 percent, and net margins by almost 5 percent, if import duties for US manufacturers on a select group of goods were to increase by 25 percent.

- The impact on profit margins may force US industrial companies to look for options to reduce their input cost by sourcing from other geographies and eventually adapt to new trade routes.

- The region that could benefit most in the near-term if US industrial companies source components and move production to tariff-friendly geographies would be the ASEAN region, especially Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Singapore, and Malaysia.

Still, where could manufacturers focus their efforts to thrive in the new trading landscape? Possible approaches to consider include the following:

- Analyze and improve trade processes as they continue to face a maze of complex import and export regulations.

- Manage supply chain risks through opening new channels of suppliers and focusing on strategic sourcing activities, including geographic concentration of suppliers.

- Build agility by altering inventory levels during periods of disruption.

- Mitigate single points of failure by developing relationships (including those involving financial support) with second- and third-tier vendors.

- Determine how to make things at a lower cost in the United States by, say, taking out components, labor, shipping time, and costs.

Deloitte’s industrial leaders expect that, if the volatility persists, manufacturers could move to managing their operations and production more regionally, as soon as in the next one to three years.5 This would require significant efforts and could redefine the global manufacturing footprint for many companies.

Take action from these insights

- Evaluate the risk from the current tariff exposure.

- Assess the visibility of your global supply network and increase investments in digital supply network (DSN) capabilities if a comprehensive view isn’t possible.

- Evaluate the ability to move production to other, more favorable regions.

- Explore what managing operations regionally could mean for your organization.

Digitization in the Fourth Industrial Revolution

The convergence of inexpensive data storage with increased computing power and Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies is transforming manufacturing at an increasing rate.6 In fact, as much as 90 percent of all data was created in the last two years, all on the heels of a substantial increase in computing power.7 However, many manufacturers have fallen behind in adopting broader digital transformation initiatives that span the entire enterprise.8

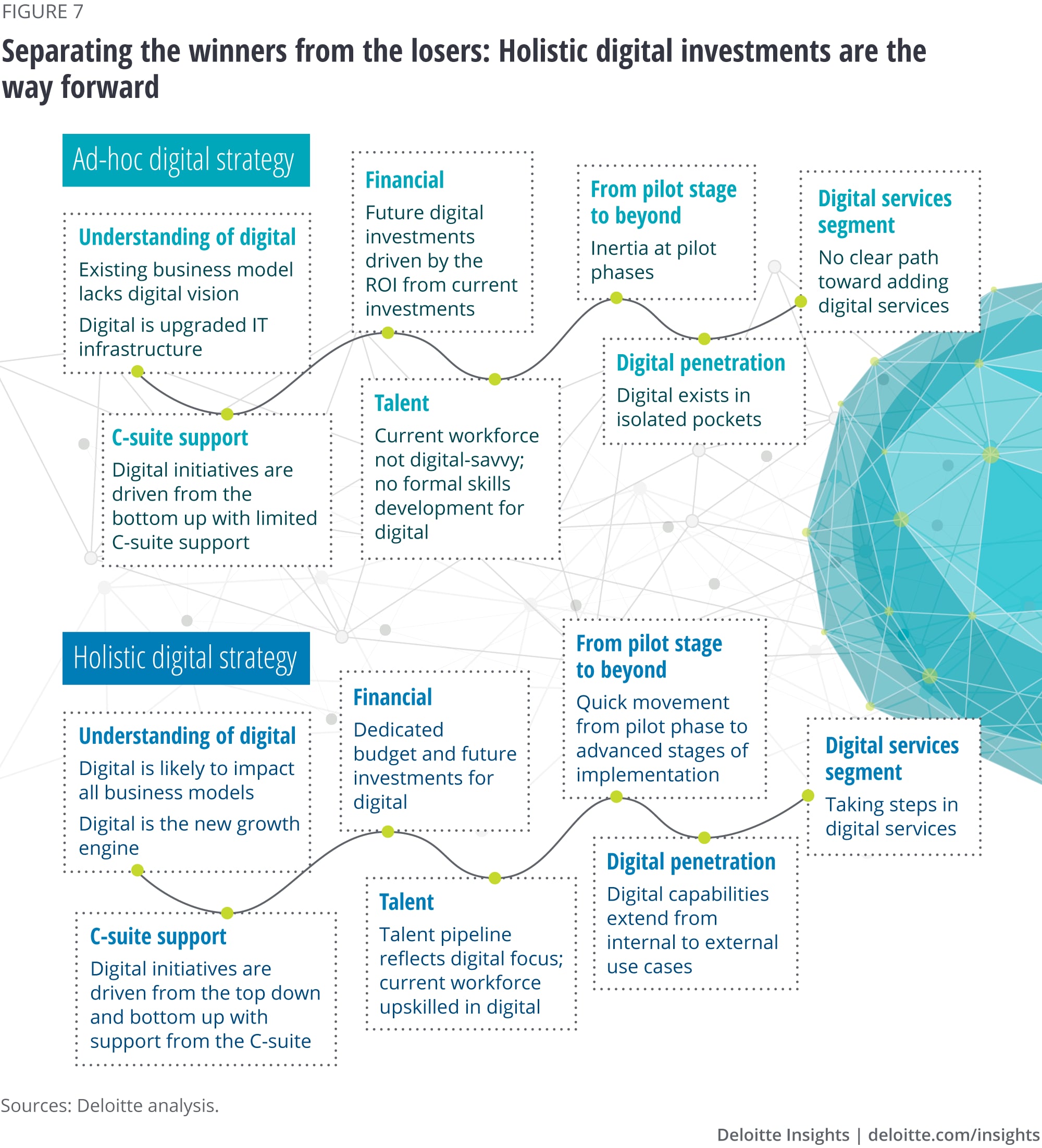

The consensus from Deloitte’s industrial manufacturing practice leaders is that if manufacturers don’t embrace digitization, as many as 35 percent of today’s industrial companies could be out of business or significantly changed in 10 years.9 In fact, in 2019, an annual C-level executive survey from North Carolina State’s Poole College of Management identified “competing against ‘born digital’ firms” as the top risk.10 The sense of urgency to embrace digitization is upon manufacturing, and digital investments in the next few years will likely separate the winners from the losers (figure 7).

Where do manufacturers stand in terms of their approach to digitization? Our 2020 global annual survey on businesses’ preparedness for a connected era had some interesting findings. Nearly two-thirds of CxOs at industrial companies said their company either had no formal strategy or was taking an ad-hoc approach to digitization.11 At the ground level, this often results in companies with several distinct business models across their product lines or brands, creating confusion in the channel/customer experience, and making the business difficult to optimize. In contrast, the 9 percent of companies that have a comprehensive, holistic digital strategy that cuts across the organization are poised to break ahead of the competition in the coming years.12 The survey data suggests that companies with comprehensive digitization strategies might be innovating and growing faster, successfully integrating Industry 4.0 technologies, and doing a better job of attracting and training the people they’ll likely need in the future.

It’s not too late to use digitization as a strategic weapon—the 2019 Deloitte and MAPI Smart Factory Study identified a cohort that is doing just that. This pioneering group of digital adopters has identified the potential value that smart factory initiatives can deliver and stepped up to invest in that potential.13 And it’s this group that has already registered benefits in the form of employee productivity and factory capacity utilization—double that of the others.14

These findings establish the urgency to make bold moves in digitization. A holistic strategy is a solid first step, and it can be combined with intentional digital experimentation to ensure companies are creating opportunities for small wins along the pathway toward broader transformation. Deloitte’s industrial manufacturing leaders identified several approaches that could enable companies to best position themselves to benefit from digital transformation.15 Each approach represents a different maturity level, but all are effective. Manufacturers should focus their digital investments in one of the following areas in the coming 12–24 months to ensure they are not left behind.

- Build out the digital core. For those companies still working in ad-hoc mode for digitization, a solid—and almost nonnegotiable—first step is to concentrate on building out the enabling core that can power the key Industry 4.0 use cases that are important to their company. This core could incorporate cloud technologies, big data analytics, and network connectivity with low latency for all areas of the business.

- Embrace Industry 4.0 technologies. For those manufacturing companies that have successfully built their digital core, incorporating advanced technologies (like augmented and virtual reality, video analytics, and machine learning) across their operations is generally a logical next step. These technologies could support a DSN that optimizes activities from product design through production and out to field services.

- Change or transform the business model. In 10 years, as much as 30 percent of new revenue for manufacturers could come from digital revenue streams. In fact, industrial companies could see a 50/50 split between selling “products” and selling “outcomes/solutions.” This is a transformational business model, and will likely require unprecedented changes, from the way companies engage with their customers through design, production, and service delivery.16

Accordingly, now is the time to make bold decisions regarding digitization in the midst of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Manufacturers that do will likely be able to see the turn of the next decade.

Take action from these insights

- Expand on your pilot programs; it is still not too late to use digitization as a strategic weapon.

- Develop a comprehensive, holistic digital strategy to take advantage of Industry 4.0 technology.

- Perform a product mix evaluation (What portion of existing product lines could likely add digital services to increase revenue or margins?).

- Take stock of your organization’s digital core (Does it provide seamless connectivity across business areas and geographies and support advanced technologies?).

- Measure the viability of shifting your product offerings to “outcome/solutions” in the coming years.

Talent and the future of work in manufacturing

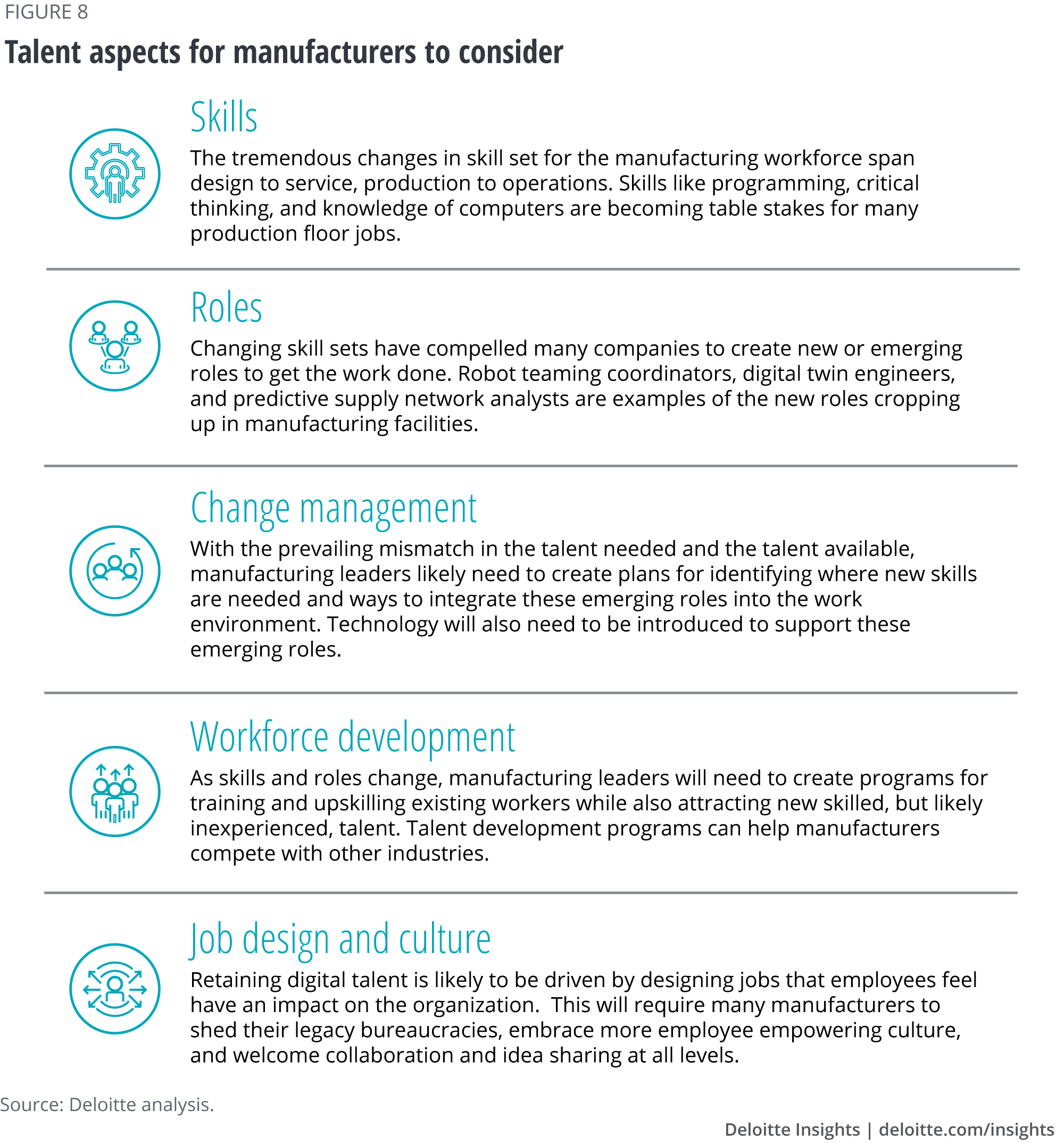

Deloitte and the National Association of Manufacturers have traced the ongoing challenges many US manufacturers face in attracting, upskilling, and retaining a workforce that is prepared for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.17 Unsurprisingly, “attracting and retaining a quality workforce” remains the number one business challenge that surveyed manufacturers report.18

Challenges related to talent in manufacturing stem from several areas, with some being beyond the control of individual manufacturers. For example, the prolonged economic boom has drained the sidelines of potential candidates for factory positions, while there is a burgeoning skills mismatch between the increasing digital skills that employers need and those of the existing manufacturing workforce. In fact, in the 2019 Deloitte and MAPI Smart Factory Study, 45 percent of manufacturers surveyed believe that they don’t have the right skills or competencies to implement an effective smart factory strategy.19 Deloitte industrial leaders have expressed concern that many manufacturers are poorly prepared for the workforce changes brought by advanced technologies.20

The demand on the manufacturing workforce for new skills is unprecedented, and is expected to require a deliberate strategy for success (figure 8).

Each of these aspects is important for the future of work in manufacturing and is expected to evolve in the coming decade, as the full thrust of digitization hits the manufacturing industry. Thus, addressing talent-related needs stemming from the fundamental shifts in manufacturing will likely require a multifocal approach.

Take action from these insights

- Define the new roles that will emerge in your organization to support the initiatives you may have around smart factory, DSN, or other digitization efforts.

- Perform a skills-mapping exercise to identify gaps between existing skill sets and those needed for digitization initiatives, like smart factory.

- Create a change management strategy to more effectively absorb the new capabilities that digitization brings.

- Identify workforce development frameworks that will meet current needs in terms of skills and roles, while also creating a talent pipeline for the next five years or so.

The rise of electrification

The sound of the manufacturing industry’s drumbeat toward sustainability is slowly getting louder. One of the key enablers is electrification, and the shift toward electrification in fleets, factories, warehouses, and offices is real.

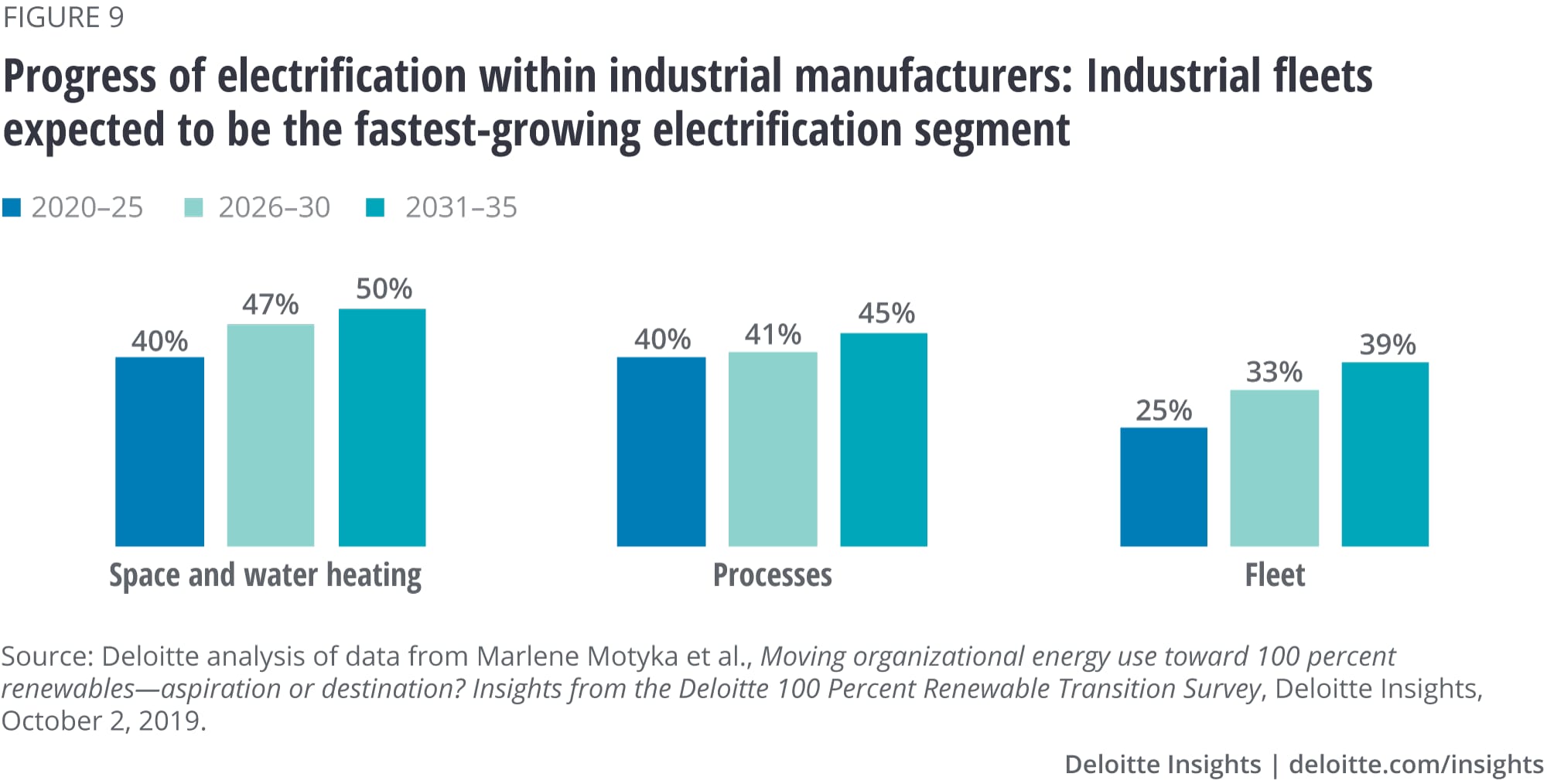

In manufacturing, a combination of the push toward environmental, social, and governance (ESG) measures, increased investor awareness, and the potential for cost efficiencies and savings is driving increased adoption of electrification. Overall, electrification in industrial companies is segmented as: fleets, processes, and facilities (i.e., space and water heating). In a recent Deloitte survey, industrial manufacturers indicated that they target electrifying almost 40 percent of their fleet by 2035.21 As for space and water heating, they’re targeting 50 percent, and 45 percent for electrification of processes.

Where and how these changes take place depend on a number of factors, from cost parity to technology maturity. Specifically, Deloitte’s 2019 Resources Study evaluated the pace of adoption of electrification for industrial processes, spaces, and fleets. Deloitte’s 2019 100 Percent Renewable Transition Survey identified a disparity in adoption rates across three particular categories (figure 9).22 For that reason, fleet electrification could likely be the major focus area in the coming years, with a target increase of almost 14 percent between 2025 and 2035.

Industrial fleets: Running on electricity

According to Deloitte analysis and the 2019 100 Percent Renewable Transition Survey, the primary area of focus for electrification in the coming decade by industrial companies is their industrial fleets. A recent Deloitte survey found that electric-powered vehicles (from vans to service trucks) could make up almost 40 percent of industrial fleets by 2035, compared to nearly 20 percent now.23 This is still years from happening and there are a number of reasons that executives offer to explain the slow adoption rate, including lack of management buy-in and funding.

There are certain challenges—introducing a disruptive new technology into industrial fleets could upset the existing supply chain for services and spare parts, while building charging infrastructure could be costly. Additionally, reliability, battery costs, and product knowledge among fleet owners and the service workforce present challenges to adoption.

That said, policy and regulatory influences (like country-level emission regulations) could push adoption more quickly. Country-level emission regulations, such as carbon dioxide fleet targets, and local access policies, such as emission-free zones, should spur adoption to the extent manufacturers have their own fleets. In the United States, phase 2 emission standards, passed in August 2017, target trailers and heavy-duty pickup trucks to reduce fuel consumption by 9 percent and 17 percent, respectively, by 2027.

Deloitte analysis projects that over the coming years, the total cost of ownership of battery electric vehicles will likely be on par with their internal combustion engine counterparts.24 Industrial manufacturers that take early steps toward an electrification strategy could gain a head start in creating an efficient green ecosystem.

Industrial processes: Changing how production is powered

The ongoing move toward electrification of industrial processes (e.g., chemical treatment, cutting, metalworking, and molding) seems to continue for a number of reasons. Electric systems have a superior design, yield, process controllability and flexibility, quicker start up times, and higher performance over their lifetime. This also means a higher energy cost, but electric systems could still become the preferred option.25

Here’s why: While initial equipment and installation costs of electrified equipment may be higher, their low operating cost, increasing efficiencies, and a high penetration rate of electrification (45 percent target by 2035, according to the Deloitte survey) can all enable companies to achieve their return on investment (ROI).26 However, cost parity will likely remain the main driver of adoption, although burgeoning ESG efforts are increasing focus and investment in the coming years. As Deloitte analysis shows, adoption is expected to be moderate, with industrial companies planning to increase their footprint by only 5 percent over the next 15 years.

Industrial spaces: Capturing ROI from space and water heating

The confluence of electric-powered facility heating and cooling systems and the rise of smart, connected building management systems is a powerful combination. It could be a catalyst for using electricity to optimize industrial spaces, including factories, warehouses, and offices. Electric-source heat pumps for industrial applications could be more cost-competitive by 2035 than conventional gas-based space heating, mainly driven by higher efficiency.27

Smart connected HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems and building climate-control systems enable a host of benefits to facility managers, such as forecasting demand and better control of ambient temperature parameters, which could increasingly become an important aspect of industrial space retrofitting and a standard choice for greenfield buildings. While industrial spaces are not an area of priority for electrification, in the coming five to seven years, manufacturers are expected to continue to explore how changing the way they manage their climate control can influence cost savings and broader ESG measures.

Take action from these insights

- Consider the timing of cost parity and technology maturity for electrification across industrial processes, spaces, and fleets. Work with your vendors/providers in each area to create transition plans.

- Create a plan that reflects the varying adoption levels for each area. Include with “shorter-timeframe” milestones in each of the three areas, modifying them as policy, customer expectations, regulations, and technology continue to evolve.

- As a current or potential industrial fleet owner, evaluate the cost and benefits in line with the regulatory environment and create a strategy for starting the transition to electric vehicles in the coming decade.

- Redesign maintenance/spare parts programs to incorporate the transition from internal combustion to battery-powered engines.

Final thoughts

There is no doubt that the manufacturing industry is facing a number of disruptive forces and that the new normal will likely be one of creating resilience ahead of it, using digital technology to anticipate the changes coming as early as possible. Five of them, in particular, are worth noting:

- Economic cycles

- Trade dynamism

- Digitization

- Talent and the future of work

- Electrification

Keeping these five factors top of mind and creating actionable plans for each can mitigate some of the uncertainty of the coming years.