Oil, gas, and the energy transition

How the oil and gas industry can prepare for a lower-carbon future

Stanley Porter

Duane Dickson

Kate Hardin

Thomas Shattuck

Energy transition amid economic disruption

In the wake of COVID-19 and the related economic downturn, the oil and gas industry faces an array of issues ranging from employee health and safety to capital constraints. Many of these concerns are familiar to industry executives who have made careers of managing uncertainty. But the new twist here is the severity of the downturn and the health risks and their simultaneous occurrence. As companies find their footing after the downturn, the extent to which executives can continue to focus on longer-term priorities such as decarbonization and positioning for the energy transition is being questioned. Indeed, the recent oil price decline and demand downturn may make it even harder for executives to deliver dividends and meet investor expectations. Deloitte’s recent study Navigating the energy transition from disruption to growth, found that some areas of investment are expected to be put on hold as companies address immediate and critical challenges, including most investments in new technologies and new business areas which would position these companies for the energy transition.

Learn more

Explore the Energy transition series

Browse the Oil, Gas & Chemicals collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

But in the longer term, the transition toward a lower-carbon future remains on track, particularly for the larger integrated oil and gas companies. This is due in part to the need to retain their competitive position as energy providers in a growing market in which newcomers are competing to provide cleaner energy to consumers and businesses alike. In addition, the current downturn and price volatility have shown that these companies’ sustainable investments and increased asset diversification have added some value even during the crisis. Pressure from consumers, investors, and policymakers toward a lower-carbon future is not expected to abate longer term. Our energy transition survey results indicated that oil and gas executives were already well aware of the importance of decarbonization: Seventy-one percent of CEOs listed “improving the environment” as a key benefit of their decarbonization strategies, and 56% reported that their decarbonization goals were linked to executive compensation, a higher percentage than noted in the utilities and the industrial manufacturing sectors.

Consumer and executive concerns over carbon and other greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have already driven global investment in wind, solar, and other alternative energies to more than US$350 billion per year and subsequently reduced dependence on fossil fuels to power our economies.1 Oil and gas companies have played a role in the progress to date—a role that could continue to increase as nonfossil fuels compose a larger portion of the energy mix in the coming decades. For example, five European oil and gas companies have announced net-zero 2050 ambitions so far.2 And despite the economic and health impacts of COVID-19, the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative in May 2020 reaffirmed the commitment of its member companies, which include a dozen producers worldwide, to accelerate their emissions reduction efforts, support the development of low-carbon technologies, and invest in opportunities to scale up carbon capture, use, and storage.3 As other companies expand their health, safety, and environment (HSE) and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) programs, the number of oil and gas companies investing in the energy transition will likely grow.

To dive deeper into how oil and gas companies can shape the future energy landscape (see sidebar, “The six channels driving the energy transition”), we have combined analysis of what companies have said publicly about their plans with our own proprietary survey of executives at energy companies today. Analysis of companies’ decarbonization strategies shows that company size and regional presence are often key determinants of action plans. In addition, our survey results demonstrate that views and approaches to decarbonization tend to differ across functions in an organization.

The six channels driving the energy transition

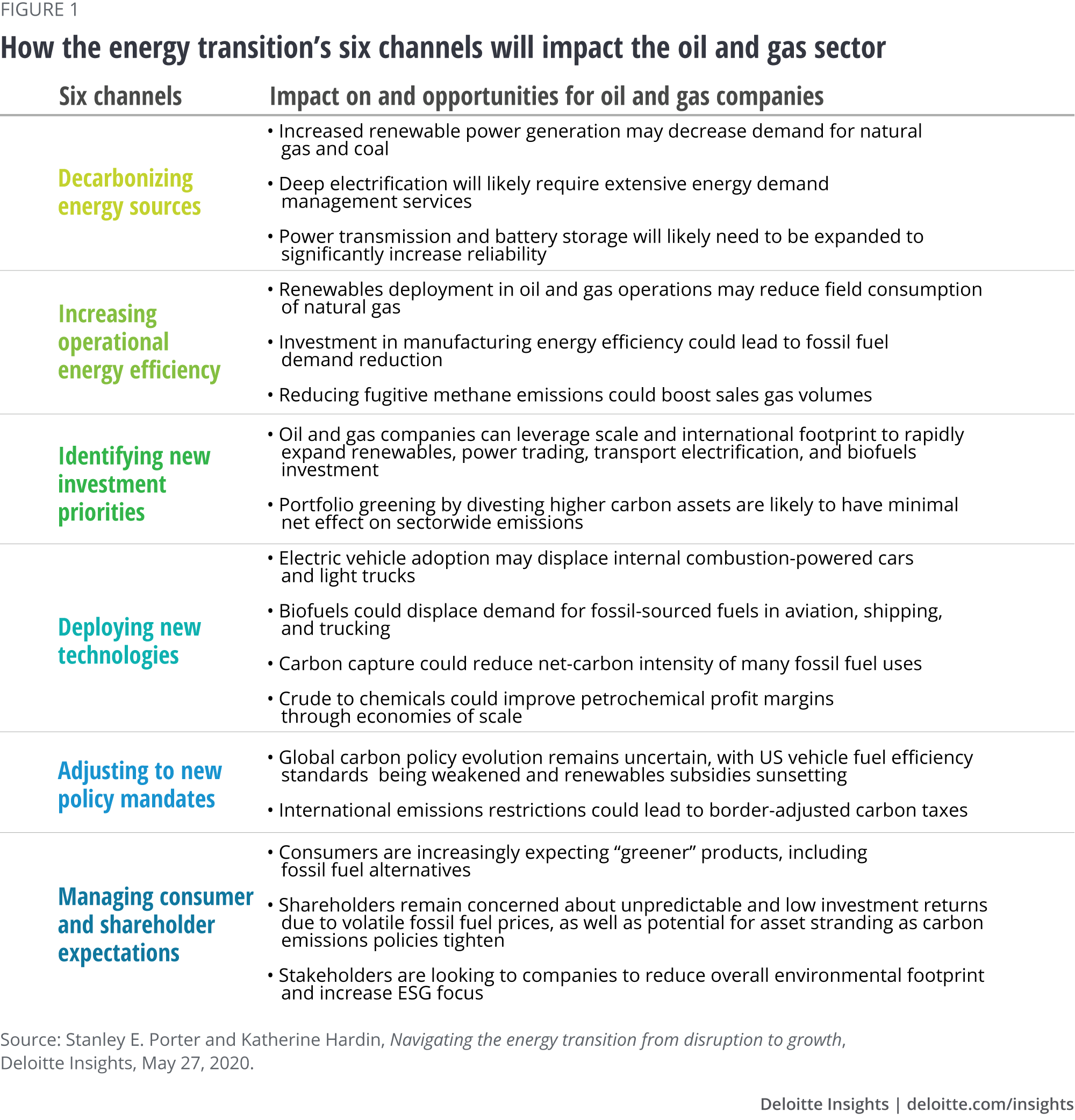

In Navigating the energy transition from disruption to growth, we outlined six channels driving the energy transition across the broader energy, resources, and industrials sectors including oil and gas companies, power utilities, chemical companies, and manufacturers. The six channels include decarbonizing energy sources, increasing operational energy efficiency, identifying new investment priorities, deploying new technologies, adjusting to new policy mandates, and managing consumer and shareholder expectations (figure 1). Oil and gas companies will likely need to leverage all six channels to prepare for a lower-carbon future.

Different circumstances necessitate different strategies

The energy transition will play out over decades and through industry cycles, but many oil and gas companies are already taking steps to cut their carbon emissions. For example, in our recent survey on the energy transition, more than 90% of oil and gas respondents said their company has or is developing a long-term strategy for a sustainable, low-carbon future. Furthermore, 50% of oil and gas respondents said their company is already investing in energy efficiency, cleaner fuels to power field operations, and acquiring businesses outside their core focus.

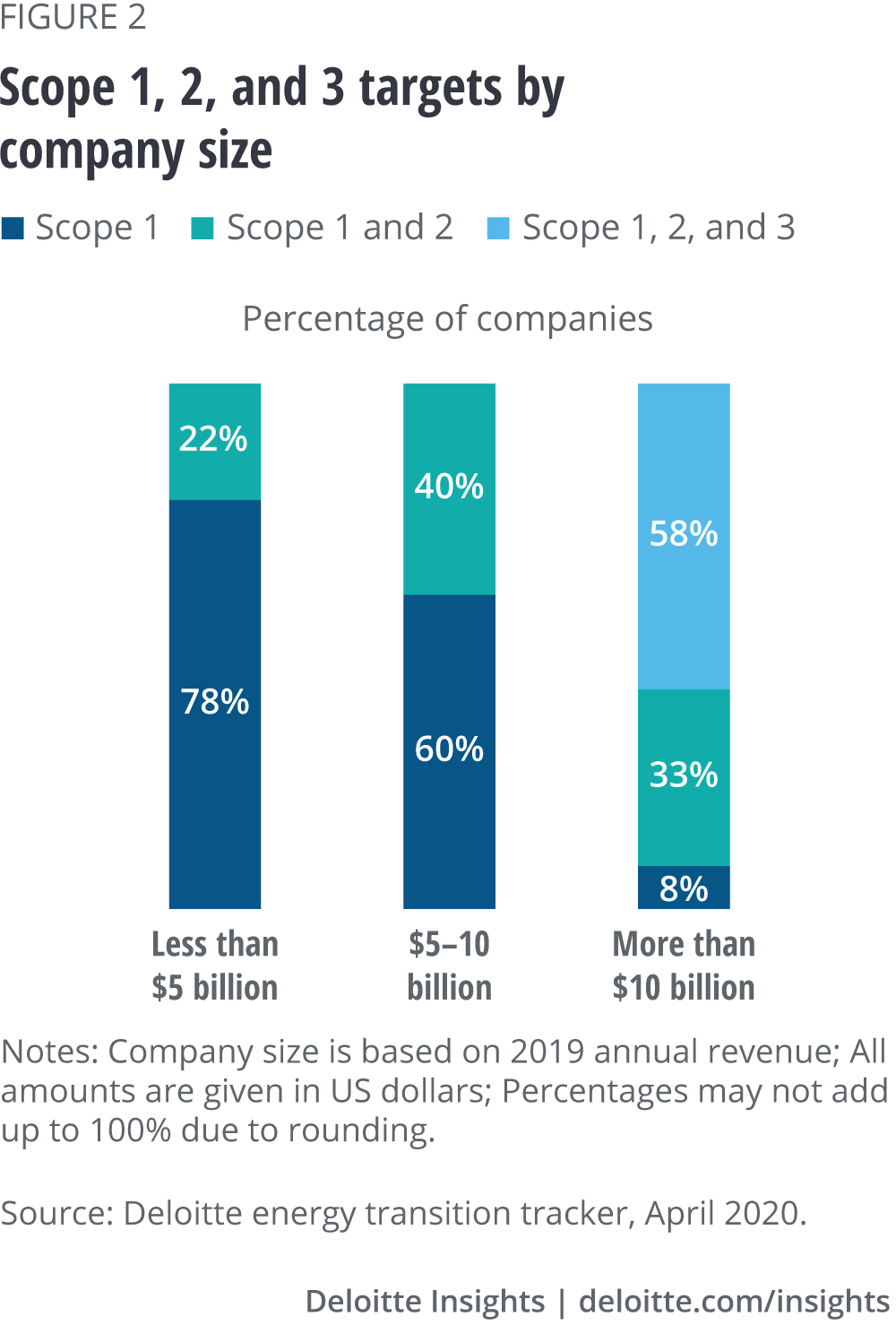

However, different companies are taking different approaches, with their reduction targets clearly differentiated by size. For example, only seven companies have so far publicly announced they are targeting Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions (see sidebar, “What are Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions?”), and only three have announced a Scope 3 globally net-neutral target—all of these companies are among the largest international oil companies (IOCs).4 Most other companies focus primarily on Scope 1, or Scope 1 and 2 emissions, with targets and company size correlated (figure 2).

The IOCs that have focused more broadly on their GHG footprint by targeting Scope 3 emissions have set long-term timelines, often 2050, and aim to substantially reduce the energy intensity of their products, including targeting net-zero emissions. These companies have also invested substantial sums outside their core business—for example, in renewables and natural gas–fired generation, electricity demand management, energy storage, and vehicle electrification. They have also increased spend on biofuels R&D and petrochemicals. Overall, these IOCs are in a class of their own, in some cases spending up to 5% of their capex budget on lower-carbon projects, a sum larger than what most other independent oil and gas companies are spending combined.5 Other large companies have begun to follow in their footsteps, ramping up biofuels research or taking incremental steps into the power markets, but progress has been slow for some.6

What are Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions?

GHG emissions can be classified by source as Scope 1, 2, or 3. Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions from operations, including burning produced gas on site to power pumps and compressors and gasoline and diesel burned to power a company’s vehicle fleet. Scope 2 includes indirect emissions that are used to power operations such as third party–generated electricity as well as process heat and steam common in refining and petrochemicals. Scope 3 emissions include those generated by producing the raw materials purchased by the business and—significantly—the emissions from using the company’s products. Scope 3, unlike 1 or 2, covers broader life cycle–type emissions that holistically capture a company’s footprint.

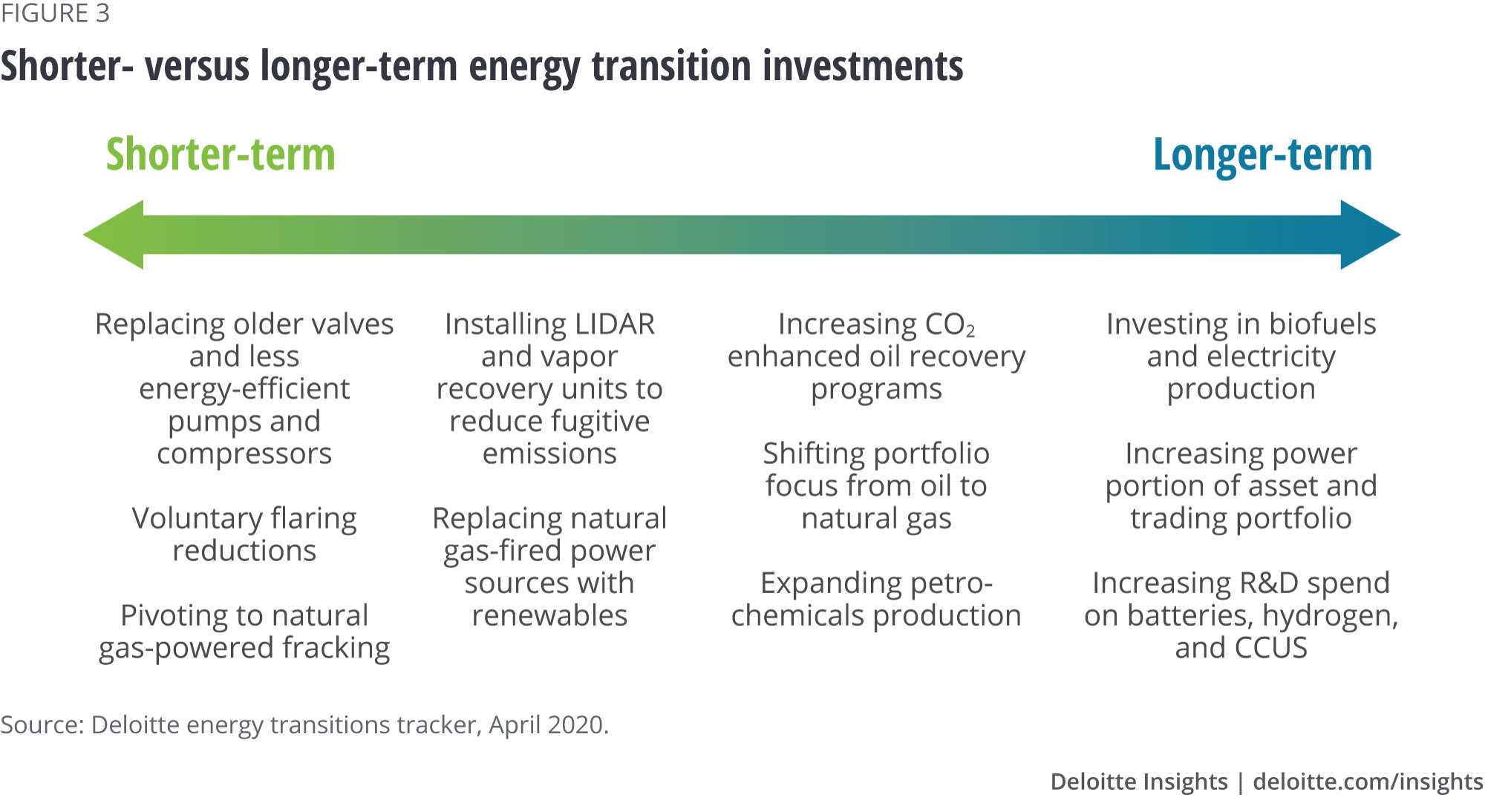

For oil and gas companies, reducing Scope 1 emissions can be straightforward, including replacing older kit with more energy-efficient equipment or installing LIDAR to identify methane leaks. Increasing onsite renewables power generation can also cut Scope 1 emissions and improve margins by saving natural gas for future sale. Reducing Scope 2 emissions can be more challenging, requiring companies to source energy from lower-carbon sources, not always available in some geographies. However, Scope 3 emissions reductions will likely prove the most challenging and would have the largest impact. End-user fuel consumption represents 80% to 90% of some oil and gas companies’ total GHG emissions. Reducing Scope 3 emissions requires a two-fold approach. First, companies would need to reduce the carbon intensity of their total energy sales by increasing the proportion of renewables and biofuels in their portfolios. Second, companies would need to invest in net-negative technologies such as carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) to offset emissions from their natural gas and fossil fuels sales.7

Ultimately, companies should focus on reducing Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions as part of their HSE and ESG programs as they contribute to their environmental footprint. This requires companies to invest in a range of both shorter- and longer-term technologies (figure 3).

In contrast, many mid-to-large companies are focused on Scope 1 and 2 emissions reductions and have set a shorter timeline: Most surveyed plan to reduce GHG intensity of production by 15% to 30% by the mid-2020s or 2030 at the latest.8 While these companies represent a sizeable wedge of the global production, the ability to rapidly scale emissions cuts could be hampered by their often wide geographic footprint and smaller spend on zero-carbon energy sources. These targets will likely increase over time, reflecting both changing market expectations as well as the increased availability and reduced cost of energy efficiency technologies.

Unlike larger oil and gas companies, most small-to-mid-sized E&Ps are targeting only Scope 1 emissions and often have not set explicit timelines. Furthermore, their targets are typically narrower, focusing on specific GHG sources such as methane leaks rather than topline carbon emissions.9 These companies have mainly expanded their traditional HSE focus to incorporate carbon into their sustainability reports, highlighting water recycling and community investments alongside flaring reductions. Even when a carbon reduction goal is absent, many small-to-mid sized oil and gas companies are taking ESG programs seriously—Diamondback announced in its first quarter 2020 earnings that flaring, GHG emissions, water recycling, fluid spill control, and worker safety targets will account for 15% of management’s short-term incentive compensation.10

Company size and regional presence are not the only drivers of decarbonization strategy; a respondent’s position in the value chain and their business function are also factors. For example, 68% of midstream respondents indicated that the energy transition would have a positive impact on their company, versus 60% of upstream and 56% of downstream respondents. However, those at downstream companies believe their companies are taking more steps to prepare for a lower-carbon world and were bullish on the potential of technology to improve their company’s resilience. Seventy-two percent of downstream respondents reported that digital technologies that improve energy efficiency and management could accelerate their organization’s transition toward a sustainable, low-carbon future.

Responses to the survey differed depending on the respondent’s functional role, such as marketing, finance, operations, engineering. For example, nearly 100% of respondents in marketing functions believed their organization was somewhat or completely ready for the energy transition, much higher than that in operations at 77%, engineering at 44%, or finance at 20%. In fact, finance proved less sanguine about what steps their companies had taken so far or would take to adapt to the energy transition, except for investment in carbon capture. Operations and engineering respondents, however, were generally confident that a wide range of technologies could improve their organization’s resiliency. This apparent gap could indicate that progress made in pilot projects and in initial R&D has not permeated through different business functions. Alternatively, however, it may be a sign that companies should continue analyzing the costs and benefits of carbon reduction strategies.

Ultimately, emission reduction goals will likely prove a moving target. Over the last few years, there has been a clear evolution with some companies, mainly those targeting Scope 2 and 3 on top of Scope 1 emissions, providing more in-depth guidance on ESG metrics with a specific emphasis on carbon. Only since December 2019 have some companies announced Scope 3 targets with net neutral ambitions. While the recent downturn may delay carbon reduction plans as companies find their footing, shareholder expectations will likely continue to evolve along with consumer preferences and policy mandates. Subsequently, oil and gas companies will likely need to increase their ambitions as well as their reporting. We are likely to see even smaller companies expand their HSE and ESG frameworks. This evolution could be critical because there is still a significant gap between what companies have announced so far versus what will likely be necessary to reduce carbon emissions in line with sub-2 degrees Celsius scenario in line with the 2016 Paris Agreement’s goal.11

Investing in technology

With most oil and gas companies’ emissions coming from Scope 3 sources, mainly fuel consumption, the current focus on reducing Scope 1 and 2 emissions can only be a starting place rather than an end goal. Reducing GHG intensity of oil and gas production, transport, and refining would lower emissions over the course of the 2020s but could hit a wall by the 2030s without widespread electrification as low-cost options such as reducing older equipment and implementing leak detection and repair programs are exhausted. Investing in technology could be critical to meeting the low-carbon imperative. Fifty percent of oil and gas respondents in our survey indicated that they would invest in digital technologies to boost energy efficiency and in operational technologies such as carbon capture to reduce future emissions (see sidebar, “Net-negative carbon technologies in the United States”). Similarly, more than half indicated their carbon reduction strategies would leverage organic investment, including R&D as well as collaborations with academia and startups. Many companies are also relying on their vendors and suppliers, with 59% planning to develop new strategies to work with their vendors to lower carbon intensity through the entire supply chain.

Net-negative carbon technologies in the United States

US oil and gas companies’ energy transition strategies are often compared to those of their European counterparts. But the abundance of relatively cheap natural gas in the United States creates different options for the US companies. According to our survey, 49% of oil and gas respondents report that their companies are focused on developing sustainable or lower-carbon products as part of their carbon reduction strategy, including natural gas. In many cases, companies are reducing flaring and methane emissions and using more natural gas and other low-carbon fuels in operations. But cheap natural gas is also an input into hydrogen production, which could yet prove to be an area in which the US oil and gas companies could leverage existing expertise. If combined with CCUS, hydrogen could be another low-carbon option. Affordable, zero-carbon hydrogen could provide companies with an alternative to fossil fuels in applications where renewable electricity and battery storage may not work.

CCUS technology is already an area of investment for many US oil and gas companies, partly due to the United States’ geological advantage for storage. CCUS can be combined with traditional fossil fuel manufacturing plants including those that produce biofuels to capture and inject carbon dioxide underground or convert it into chemicals products such as methanol. The US government has incentivized CCUS through its 45Q tax credit, which targets carbon capture and injection for both carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery and long-term sequestration, as well as carbon emissions reductions through use in industries such as chemical manufacturing. Beyond tax incentives, the US government has also invested in R&D with the U.S. Department of Energy providing almost US$250 million for domestic CCUS research and pilot projects in the past two years, building on its prior research developed through its Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnerships started in 2003. These projects could promote technologies that could reduce emissions from plants across the energy and industrials sector.12

The United States may have an edge in both CCUS and hydrogen because developers can leverage the United States’ preexisting extensive pipeline infrastructure for storage, transport, and distribution. Moreover, the lower population density and significant petrochemical and manufacturing industry may make electrification more challenging. Using green hydrogen to power energy-intensive industries and offsetting any carbon production through CCUS may make more commercial sense, particularly in regions with low renewable energy potential. Ultimately, both CCUS and green hydrogen could be needed to reduce global carbon emissions, and particularly for countries with significant fossil fuel resources such as the United States.

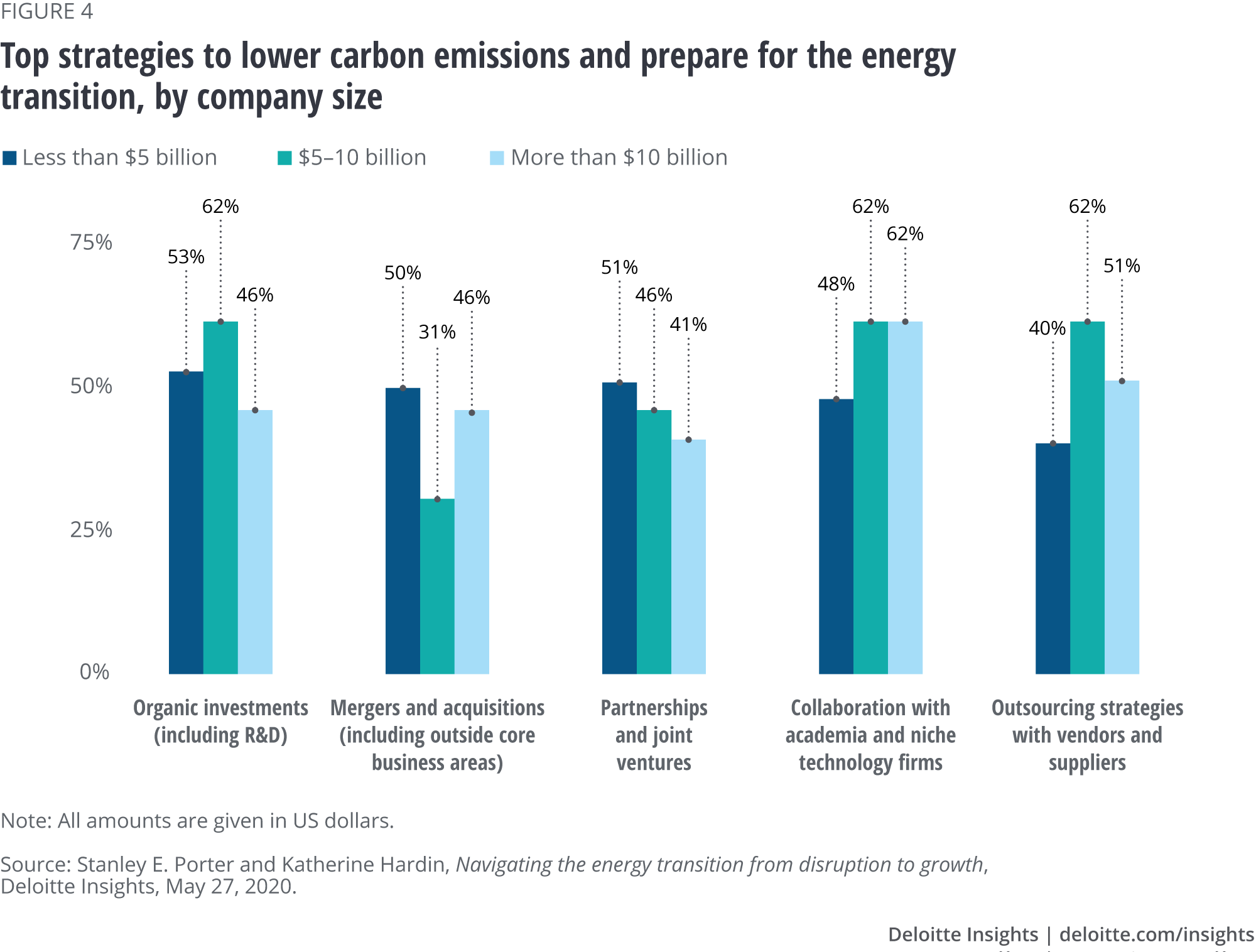

Companies’ approach to partnership in achieving lower-carbon operations also varies substantially by size, with larger companies emphasizing collaboration and outsourcing over organic investments and joint ventures. Many smaller companies are pursuing the opposite approach (figure 4), which reflects in part their past strategies and their current asset portfolio. For companies focused on replacing older, less energy efficient equipment, or reducing flaring, organic investment or working with joint venture partners will likely remain a high priority—particularly if their portfolio includes substantial non-operated assets and older fields. However, for the IOCs looking toward investment in zero- and negative-carbon technologies, working with academia, startups, and vendors is expected to play an increasingly important role.

Even for the largest spenders, however, low-carbon spend is often less than 5% of their capital budget.13 More than 40% of survey respondents expect their companies to increase low-carbon spend up to 10% of their budget over the next five years, but based on the last decade and current economic downturn, that may prove too optimistic. Partnerships could make organic and inorganic spend increase further, but companies will likely find there is no one-size-fits-all answer.

Many companies have begun to invest in technologies and business models outside of their core oil and gas operations. For example, Equinor now spends 25% of its R&D budget on low-carbon and energy efficiency technologies, and plans to operate up to six gigawatts of renewable electricity generation capacity by 2026.14 Total recently announced its US$3.7 billion acquisition of a major stake in a 1.1 gigawatt British offshore wind project.15 Other companies such as Shell have increased their renewable electricity portfolio and invested in new energy startups.16 Such investments allow IOCs to retain their role as energy providers by including in that portfolio a growing share of low- or zero-carbon energy options. Many of the larger integrated US companies have not followed this playbook, primarily focusing on biofuels and carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery.

Next steps for oil and gas companies

Most oil and gas companies have made headway in reducing their carbon intensity and are assessing which investments and technologies could drive further progress. Their approach will likely need to be holistic, examining the entire value chain including sourcing, operations, and sales. In sum, there appear to be two main levers most companies are using to reduce their long-term carbon footprint.

The first lever is eliminating almost all Scope 1 and 2 emissions. While many companies we surveyed have already made progress in reducing waste emissions from flaring or methane leaks, widespread deployment of renewables as well as including electric- or biofuel-powered vehicles in company fleets would be needed to bring emissions down to almost zero. Reducing vendor emissions could be key as companies take a hard look at their outsourcing strategies and supply chains, including oilfield service providers, to identify how carbon can be further wrung out of their operations.

And second, many companies are investing in and deploying net-negative carbon technologies. Nevertheless, from a practical standpoint, the only way to achieve near net-zero emissions in the next few decades might be by leveraging technologies that remove carbon from the product life cycle, either by sequestering carbon into noncombustible products (i.e. plastics, not fuels) or by capturing and injecting carbon underground with CCUS or as part of carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery. Partnerships and collaboration could be key. Internal R&D can help commercialize negative carbon technologies, but so would leveraging research from academia and new technologies developed by startups.

Even after taking these steps, achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 is likely to be challenging. However, as progress continues along the six channels of the energy transition, oil and gas companies are adapting and positioning themselves to provide lower-carbon energy to consumers around the world. Much progress has been made, but policy mandates, consumer preferences, and shareholder expectations may continue to change.