2024 Deloitte-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study

State chief information security officers are striving to counter ever more sophisticated threats and build resilience

Foreword

2024: Bigger threats, bigger responsibility for CISOs

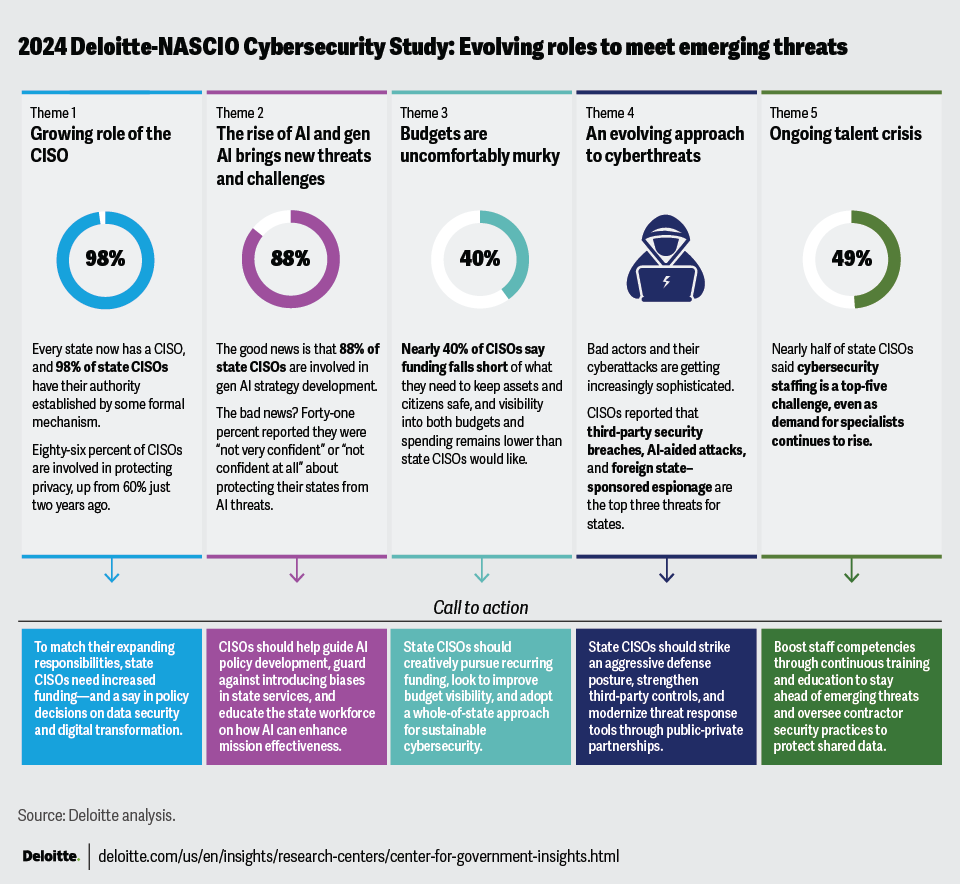

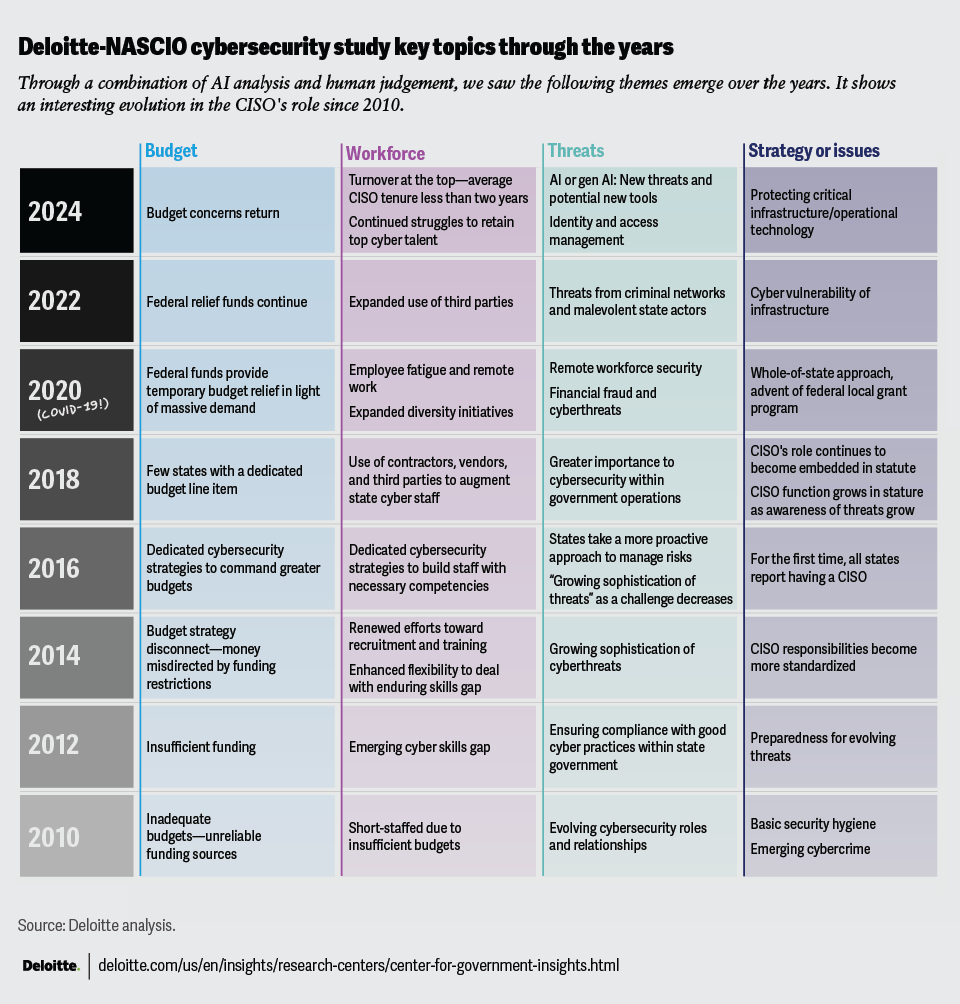

The 8th biennial Deloitte1-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study reveals a landscape roiled by fresh challenges, most notably the extensive advances in artificial intelligence and generative AI. This year’s study reflects insights from the CISOs of all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The CISOs completed this year’s survey in spring 2024, at a time when the massive disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic had subsided, but fresh cyberthreats had emerged.

The attack surface is expanding, with the public sector’s reliance on information becoming increasingly central to the operation of government itself. The ability of government to deliver on its mission rests on data—and on the security of that data.

As cyberspace grows, more of the world’s economy, public services, and infrastructure rely on the cyber-resilience of information networks.

The continuing growth of CISOs’ roles in an increasingly dangerous threat environment emerged as a major theme of this year’s survey.

The rise of AI and gen AI, bringing both substantial risks and new opportunities, is far from the only challenge facing states today. Budget concerns for CISOs—which federal COVID-19 recovery funds briefly aided—have returned in force. And ongoing workforce challenges make a difficult task even harder: It simply isn’t easy to retain top-notch cybersecurity professionals in a tight labor market.

The stresses of the pandemic have also translated into turnover at the top. It’s no secret that security professionals work under enormous strain, with a number of recent studies and surveys citing frequent burnout.2 Since our 2022 survey,3 nearly half of the states—23 of them to be exact—have new CISOs. The median tenure of a state CISO is 23 months, down dramatically from 30 months two years ago.4 However capable and talented these new leaders may be, turnover can be disruptive.

The good news is that state governments increasingly recognize the critical role that CISOs play, formalizing their authority. It’s promising, though there’s plenty of progress yet to be made.

The survey results helped us identify five common themes reflecting the specific challenges that state CISOs are facing—and takeaways suggesting what they might do to move forward.

- The expanding role of the state CISO

- The hazards and opportunities of gen AI

- Budgeting and funding remain uncomfortably murky

- An evolving approach to cyber threats

- The cyber workforce—foundational to everything

We appreciate the participation of 50 states and the District of Columbia whose representatives responded to our detailed survey, including some open-ended questions. We applaud participants’ ongoing commitment to safeguarding citizen data and state institutions.

The CISO role: An expanding role in uncertain times

Government is becoming increasingly digital. To operate, state governments need to both enable the sharing of critical information and maintain the confidentiality of that data. To deliver services efficiently and inspire citizen trust, governments are increasingly leveraging digital technology. Not surprisingly, cybersecurity has taken center stage.

The attack surface is growing. More information is flowing online as well as through the Internet of Things. More servers in more places than ever hold the public’s health, financial, and more personal data. More critical infrastructure—including transportation, water, and power—are integrated with online operational components. All of this creates a greater number of sites of vulnerability, and state officials are recognizing information security as foundational to the efficient functioning of essential government services.

The public sector is an attractive target for both foreign state actors and criminal enterprises. The cyberthreats confronting state and local governments are wide and varied, often leveraging highly sophisticated approaches. The City of Oakland, California, for example, faced a serious ransomware attack in February 2023.5 And the UK Electoral Commission was the victim in 2022 of what it called a “complex cyberattack” that exposed a broad range of information relating to 40 million registered voters.6

There’s no mystery why interest in information security is rising, especially given the high stakes when things go wrong.

Not only are malicious external threats growing, the emergence of AI, especially gen AI, has also introduced new mechanisms for exploiting human vulnerabilities. In addition to boosting the effectiveness of phishing scams that seek to fool employees and contractors into divulging sensitive information, gen AI’s ability to produce audio and visual deepfakes adds another level of potential deception. With everyone looking to the state CISO to lead the effort to protect citizens and systems, the role is rising in prominence; indeed, the survey results suggest that the CISO is now firmly established as a central part of most states’ information technology organizations.

Nearly every state now relies on CISOs for a range of key services, particularly security management and operations (98%); strategy, governance, and risk management (98%); and incident response (96%) (figure 1).7

The state CISOs reported a significant expansion of their role in maintaining data privacy, jumping from 60% in 2022 to 86% in 2024 (figure 1). This may be explained at least in part by the increase in state laws and statutes aimed at protecting consumer privacy,8 even if some of those laws and statutes have thus far been less effective than hoped.9 As gen AI heightens concerns about corporate uses of online data,10 CISOs might expect a continued increase in their data privacy responsibilities.11 As of 2024, 20 states have comprehensive data privacy laws in effect.12 Our survey shows that more CISOs are taking on responsibility for privacy compared to those in the 2022 survey. In some cases, CISOs may be performing dual roles as both CISO and chief privacy officer (CPO), while in other cases, the CPO might be reporting to the CISO.13 Our survey shows that only 21 states have CPOs.14

The scope of CISOs’ work is expanding to encompass some high-salience areas and shrinking in other tasks. For instance, 10 fewer state CISOs than in 2022 report taking responsibility for physical security—that is, the security of data centers and other buildings (figure 1). One factor: Only six CISOs report that their states’ cybersecurity budgets cover physical security, down dramatically from 15 in 2022.The trend could also be an indication that states are consolidating data centers and moving to third-party cloud providers.

Every state now has a CISO, and in most cases, the CISO’s authority is formal, typically established by a state administrative rule or statute (figure 2).

States are instituting statutes, legislation, or both on some elements of cybersecurity—for instance, cyberthreat information sharing (figure 3) on which some states now give CISOs more authority—while other areas remain more informal.

Regardless of how formal or ad hoc–specific responsibilities are, CISOs will have crowded daily itineraries for the foreseeable future. In volunteering their top cybersecurity initiatives for the next year (figure 4), survey respondents drew up a robust agenda that includes established activities including risk assessments and monitoring the security operations center, and other areas of the digital enterprise such as citizen digital identity and election security. The CISOs’ broad mandate suggests that state leaders are looking to them to help achieve a variety of critical goals, including protecting government-held data, securing citizen-agency interactions, and boosting overall trust in public institutions.

Action insights

Based on these findings, state CISOs can consider the following courses of action.

- Continue to make the case for robust cybersecurity. The responsibilities of state CISOs have expanded, while the authority and funding have not always kept pace. Cybersecurity issues will probably continue to escalate—especially with gen AI applications rapidly multiplying—and the CISO role is likely to continue expanding. CISOs need resources to support these expanding responsibilities. Public leaders throughout state government—from governors to legislators, from CIOs to agency leaders—need to understand and support the funding of cybersecurity.

- Promote the CISO’s role in digital transformation. As states increase their use of online transactions with constituents, the state CISO should have a seat at the table in helping to inform policy choices that affect data vulnerabilities. Areas such as digital identity and access management—for state workers, contractors, citizens, and businesses—should include a CISO perspective to confirm that system security is considered. The CISO’s mandate positions the state to serve as a catalyst for digital transformation, improving service to citizens as well as to agencies.

- Proactively participate in policy development. As emerging technologies grow in prominence, CISOs should consider a whole-of-state approach that includes proactively providing guidance to state and local government leaders on policy, technology, and operations relating to cybersecurity.15

- Enhance succession planning efforts. States are seeing significant turnover among cybersecurity leadership, and filling these vacancies can take six months or more. A greater focus on succession planning may help improve continuity in leadership, particularly in terms of ongoing relationships with higher education, local government, and federal officials.

Gen AI: The hazards and opportunities for governments

The gen AI genie is out of the bottle—and while this genie has immense powers, authorities need to give the transformative technology proper oversight. In the short time since its public release, the rapid rise of gen AI has leaders in both private and public sectors scrambling to balance opportunities and risks, with each new use case inspiring fresh hopes and concerns.16 At the state level, CISOs are center stage in managing gen AI threats, with nearly all involved in developing state strategy and security policy and even more expecting future engagement (figure 5). All except two state CISOs report being involved in gen AI security policy development.

Survey responses indicate that many CISOs are concerned about the unique security risks associated with AI and gen AI. Asked whether their states’ information assets are adequately protected from AI-enabled attacks, all but a handful of CISOs indicated they were only “somewhat confident,” with many reporting “not very confident” or worse (figure 6). As one survey respondent remarked, “Gen AI just makes it easier and cheaper for bad actors to continue their actions”; another cited a concern about “increased risk for security, privacy, and ethics.”

Overall, AI-enabled threats were the second most concerning form of cyberthreat (figure 7), with 71% of CISOs characterizing AI threat levels as “very high” or “somewhat high,” trailing only security breaches involving third parties and landing higher than concerns such as “foreign state-sponsored espionage” and “malware and ransomware.”

Despite registering this high level of concern regarding AI/gen AI, only one-quarter of state CISOs list implementing gen AI security controls among their top five cybersecurity initiatives for 2024 to 2025 (figure 4). As one CISO indicated: “We will need to put in more governance and security controls in place before completely leveraging gen AI.” Another summarized the state’s position: “We are in the process of developing acceptable usage policies and general guidance on how to properly use AI within state government technology. Recently, the requests for AI use at the agency level have increased exponentially and have been reviewed on a case-by-case basis, but we need to establish official guidance on its use.”

Most state CISOs appear to be moving forward with plans to formalize strategy and guardrails.17 One reported that the office is “in discovery phase with an executive order to study the impact of gen AI on security in our state.” Another “has established a committee that is reviewing use cases, policies, procedures, and best practices for gen AI.”

Strikingly, CISOs clearly see this new technology as not only a potentially dangerous tool for bad actors but also an opportunity to expand capabilities and better protect operations and citizens. Twenty-one state CISOs report that they are already using gen AI to improve security operations, with another 22 planning implementation within the next 12 months (figure 8). If the respondents' expectations of future AI use prove correct, 43 states would be using gen AI to enhance their cybersecurity posture within the next year.

“There is a high demand for gen AI services and solutions; enterprise policy has been defined but is broad,” one CISO said, suggesting plans to leverage third-party resources: “It is anticipated that we will look for private solutions that will allow for the containerization for more sensitive uses of gen AI, but at this time, we are mainly mapping potential use cases to evolve a potential statewide approach and governance model.”

Depending on the state, rules regarding gen AI use by state employees and agencies may come from the legislature, the governor, and/or specific task forces and committees. Guidelines regarding employee use of gen AI are under active discussions in many jurisdictions, and CISOs have an important perspective in this conversation. Many states have executive orders, study committees, or acceptable use guidelines in place.18 One CISO called the technology’s potential value to the workforce “extremely high.”

One CISO summed up the costs, benefits, and strategies of gen AI: “While there are concerns over the use of AI across the state, we do not want to stifle the potential benefits from its use. We are establishing guardrails for use of AI. However, we also find that we do not have a well-defined data management program which is crucial to the effective and secure use of AI. Both need to be further developed.”

States are moving at different speeds to implement gen AI policy guidelines. Only 25% of state CISOs report that they are choosing to spend a portion of their state budgets on gen AI governance and security controls (figure 9),19 suggesting that many in the budgeting process may not fully grasp the need to have guardrails and guidelines in place as soon as possible.

Action insights

Based on the findings in this survey, state CISOs may consider the following approaches.

- Bring the CISO perspective to the AI/gen AI policy conversation. As emerging technologies including gen AI grow in prominence, CISOs should consider proactively providing guidance as state and local governments set policies for secure, ethical usage of these technologies. CISOs can also consider tapping into experts from different domains to help inform gen AI policy.

- Review the operational uses of AI/gen AI. Using AI as part of state service delivery introduces issues of trust, reliability, and possible unintentional inequities in service delivery. CISOs have a role in ensuring that AI doesn’t introduce biases or create unethical distribution of services and resources. While it’s encouraging that most states are putting CISOs at the center of gen AI planning, operational risk in using AI/gen AI could increase as well.

- Educate the state workforce about the positive possibilities of AI/gen AI. CISOs and other IT staff may readily see the innovative possibilities of these new technologies. IT leaders should keep in mind, however, that some state employees may have concerns about AI. Leaders should stress the role of AI and gen AI as tools that can support workers and enhance mission effectiveness, as well as the upside of employees becoming adept at using these transformative tools.

Budgeting and funding remain uncomfortably murky

Do state CISOs have sufficient funding to get the job done? Compared with 2020, more survey respondents report adequate funding for projects to comply with regulatory or legal requirements. But nearly 40% still find themselves short of funds to address those requirements (figure 10). It is one thing to get decision-makers’ commitment and support—as nearly every state CISO claims to have—and another to translate that commitment and support into funding to bring operations up to code.

One challenge that many state CISOs face: While they told us they were highly engaged in cyber strategy and discussions, respondents reported having limited visibility into funding, possibly because many states operate in a federated model rather than one that is centralized. Nearly half of state CISOs—even more than in 2022—couldn’t readily attribute from available financial data how much of their states’ IT budget is allocated to cybersecurity (figure 11).

Perhaps a larger issue: In many states, CISOs find it challenging to secure adequate funding—an ongoing concern and source of frustration. As in the 2022 survey, four state CISOs report cybersecurity getting 1% or less of their states’ IT budget (figure 11). By contrast, federal agencies generally allocate 10% to 12% of their IT budgets to cybersecurity.20

In our 2024 survey, 35% of respondents cited the lack of a cybersecurity budget as a top-five challenge (figure 17); four CISOs also cited lack of a dedicated cyber budget. Especially with stakes so high, it’s a challenge to protect the whole range of critical assets; it’s even harder to do so without a commitment that funding and staffing will be in place when needed.

With federal agencies offering critical supplemental funding, many state CISOs tap multiple funding sources to pay for operations, often including a blend of appropriations and chargebacks (figure 13). The lack of certainty is itself a challenge at a time when information security is paramount—and when CISOs are working diligently to staff up for preventative and responsive roles. The lack of budget ownership and predictability for CISOs can make planning and execution a challenge.

With cybersecurity investment demands rising, CISOs are continually looking for not only more funding but more guaranteed ongoing funding (figure 14). While three-quarters of state CISOs report that their budgets have indeed increased, nearly 40% still say funding falls short of what they need to keep assets and citizens safe.

CISOs have found the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program21 a helpful funding boost—to a point (figure 15). One respondent, assessing the program as “not very effective,” echoed others in citing the complex guidelines involved: “The rules have defeated the whole-of-state goals of the funding. The concept of subgrants has enabled local governments to invest in nonstrategic solutions against state recommendations. There is also the loss of competitive negotiations, since we are buying individual entity licenses at significant sticker prices.”

Some CISOs were more direct: “This level of funding is not enough to make a dent on the needs across the state,” another told us. “It is off by an order of magnitude, at least if you include critical infrastructure such as drinking water and wastewater.” Overall, while CISOs appreciated the sentiment behind the grants, they often found the effort involved in administering the grants high relative to the value of the grants—in some cases, the juice wasn’t worth the squeeze.

Action insights

Based on the findings in this survey, state CISOs can consider the following approaches.

- Work creatively to boost budgets. In many cases, state CISOs have broad authority but insufficient staff and budget to deliver on their mission. While one-time infusions are relatively easy to obtain in strong fiscal times, cybersecurity is not a project with a defined end, and one-time infusions offer only temporary help for persistent funding needs. To obtain the needed recurring funding, CISOs may need to pursue creative options. This might mean making a compelling business case to political leaders; collaborating with business partners; or—perhaps—integrating security efforts into broader technology programs, from cloud and networking to state telecom contracts.

- Work to improve visibility. CISOs can work on improving visibility into both where funding comes from and where it goes. This can be helpful to state decision-makers, including legislators, in directing investments to where they’re most needed.

- Take a whole-of-state approach. State CISOs can work toward implementing a phased whole-of-state approach—encompassing local, city, and county governments as well as higher education institutions—that uses available federal and state funds to bolster a sustainable cybersecurity program.22 For example, Texas state government funds a Regional Security Operations Center Pilot Project, which leverages a public university to provide “boots on the ground” support for local governments struck by cyber incidents.23 In Tennessee, a statewide cybersecurity review program aims to identify and fill local security gaps.24

States take an evolving approach to threats

The rapidly changing landscape of cyberthreats demands that state CISOs respond with new defensive approaches. Over the last two years, states have done exactly that. Indeed, CISOs are guiding state governments’ entire threat posture through an evolution as they seek to defend against a set of threats that are constantly evolving.

These threats include sophisticated criminal syndicates and state-sponsored cloak-and-dagger attacks. The bad actors are making use of new technology, including AI/gen AI, as well as exploiting human vulnerabilities in the form of employee errors or, in some cases, breaches by disgruntled employees and contractors.25 The increasingly connected nature of information makes a wide range of physical appliances and infrastructure vulnerable, including everything from printers to satellite-based sensors.26

In 2022, CISOs were most concerned about malware and ransomware. Though still a concern, there is some evidence that governments are making progress in fending off those attacks.27 This year’s survey shows that other threats have emerged as more serious concerns—most notably, third-party security breaches, AI-aided attacks, and foreign state-sponsored espionage (figure 16). Phishing, the CISOs’ biggest concern four years ago, is a less urgent worry today though still very much on the radar.28 While hackers have only begun to exploit gen AI tools for malign purposes, defenders will likely find themselves dealing with more AI-aided attacks in the near future.29

This year, state CISOs cited a number of factors to explain why existing systems and staff are struggling to keep pace with increasingly sophisticated attackers and methods. Survey results suggest that legacy systems are falling further behind as hacker technology improves (figure 17).

As physical infrastructure such as water, wastewater, transportation, and power rely more on IT systems bad actors have targeted these critical systems’ cyber vulnerabilities, and more cyber leaders in the federal government and elsewhere are already aiming to boost awareness.30 A March 2024 White House letter alerted governors to recent attacks against US water systems by “threat actors” linked to foreign governments, noting, “Drinking water and wastewater systems are an attractive target for cyberattacks because they are a lifeline critical infrastructure sector but often lack the resources and technical capacity to adopt rigorous cybersecurity practices.”31 Because such attacks may put the physical well-being of the public at risk, in some sense, these are more consequential threats than financial extortion through ransomware.

A challenge for state CISOs is to stretch available resources to protect these critical systems and—where needed—to advocate for additional resources to meet this growing threat.

Outsourcing is an increasingly central component of states’ information security functions. It is evident that many state CISOs are tapping third parties to handle certain key tasks and functions. Topping the list: Three-quarters of survey respondents outsource their centralized security operations center, including around-the-clock security monitoring (figure 18).

Identity and access management (IAM) grew in prominence during the pandemic, when public and private sector organizations suddenly found themselves supporting a largely remote workforce. The sudden shift to “work from anywhere” strained online systems and had CISOs scrambling to support remote workers. The role of IAM was brought to the forefront, particularly for employees and contractors. An effective IAM framework can automate the task of assigning and tracking user privileges, helping protect assets across networks and limit cyber vulnerabilities. As states consider the viability of adopting a zero trust architecture, a robust IAM is a critical pillar. Rigorous identity verification, often including multifactor authentication, can help confirm that access requests are legitimate. In addition, least privilege access control only grants minimum level of access to users and devices necessary for them to perform their tasks.

Strong identity and access management is a key enabler of digital government services. As states increasingly move toward digital constituent services, IAM for the general public and employees is likely to gain more importance.

It is encouraging that 63% of CISOs reported having IAM systems in place for at least some employees and contractors (figure 19). Of those IAM systems, 94% provide multifactor authentication, 78% have single sign-on, and 53% provide privileged access management. In addition, 88% of the CISOs in states with IAM systems have responsibility to set overall security policies.

Action insights

Based on the findings in this survey, state CISOs can consider the following approaches.

- Strike a more aggressive posture. Today’s asymmetric cyberthreats demand more forceful responses. Incremental progress is important—CISOs should continuously be seeking to root out unsecure connections and shut software backdoors—but proactive efforts are increasingly necessary. State CISOs may want to explore the possibility of relationships with the private sector that can offer early warnings of viruses or hacking trends.

- Strengthen controls for third parties. As contractors, vendors, and other third parties play a key role in operations, controls such as limiting the use of contractor-owned computing devices—which can allow a contaminated device to plug into a state network—will continue to be important. Consider including third-party risk assessment services in contracts.

- Collaborate to modernize threat response. Too often, state CISOs are fighting emerging threats with outdated legacy tools and systems. CISOs should look to collaborate with public and private sector tech leaders to help modernize the approach to threats.

- Continue to advance adoption of IAM platforms, both internally and externally, especially in those states that are not currently fully operational in this area. Public-facing enterprise IAM is a particularly powerful tool for streamlining interactions, making them visible and enhancing government services.

- Build awareness and trust with regular reports for stakeholders. State CISOs should consider distributing a regular “State of Cyber” report to legislators, state leaders, and business executives, aiming to elevate ongoing and new challenges with an eye toward potential opportunities for collaboration.

The cyber workforce—foundational to everything

A skilled, professional cyber workforce is central to effective data security efforts. An effective cybersecurity strategy is only as effective as the workforce that implements it. In this year’s survey, respondents clearly indicated that workforce challenges and concerns continue to be top of mind for CISOs. These challenges include budget constraints that contribute to understaffing as well as difficulties in recruiting and retaining skilled workers.

Global demand for cybersecurity specialists continues to rise, and training efforts are struggling to make up the shortage.32 Therefore, it is no surprise that nearly half of state CISOs cited a lack of cybersecurity staffing as a top-five challenge, with another 31% citing inadequate availability of cyber professionals (figure 17).

In terms of core staff within the CISO’s enterprise security office, the data suggests that some CISOs have been able to expand headcount. Four years ago, 16% of CISOs indicated that they had five or fewer dedicated cybersecurity full-time employees, and that proportion has dropped to just 4% in this year’s survey. In general, about half of CISOs indicated they had between six and 25 cybersecurity professionals on staff, not including contractors (figure 20).

The survey shows some positive sentiment in terms of staffing skills. The glass-half-full perspective is that an increasing number of state CISOs reported that their staff possess the competencies required—47% in this year’s survey, up from only 28% in 2020. The glass-half-empty perspective: More than half of respondents—27 out of 51—still see competency gaps (figure 21). In a field changing so rapidly and with new threats constantly emerging,33 keeping knowledge and skills up to date can be challenging.

It is particularly challenging for information security offices, using public employment protocols and budget limits, to staff 24/7,34 which may help explain why 59% of CISOs report turning to third-party contractors to augment their internal teams. When it comes to responding to a cyber breach, states use a mix of resources to respond (figure 22).

In addition to staffing their own teams, state CISOs use a range of consultants and other third-party contractors for a variety of tasks—even when they lack confidence that some of those contractors’ practices are fully secure. And the number of state CISOs who feel “very confident” is falling (figure 23).

Workforce diversity: A wide range of approaches

In this year’s survey, we asked CISOs how their offices are addressing workforce diversity. CISOs offered a wide range of responses.

Some respondents expressed pride in their teams’ diverse composition.

- “The CISO office is the most diverse organization in the state. We have a perfect blend of amazing technology professionals learning, growing, and driving results together.”

- “Working with our HR office, we have developed a highly diverse cybersecurity team.”

- “Our team typically ranks as one of the most diverse teams in the enterprise here.”

Some surveyed CISOs specifically highlighted their pursuit of diversity through recruiting policies.

- “We make all attempts to support diversity through recruiting and hiring.”

- “We work to make the job postings as open and accessible as possible, while also promoting diversity efforts from the senior leadership team down.”

- “Our commitment to diversity is integral to our broader mission of establishing an inclusive, innovative, and high-performing cybersecurity team.”

Some CISOs cited policies or other circumstances that prohibited or limited diversity efforts.

- “[My state] passed legislation this last session forbidding DEI.”

- “Hiring is based on skills and qualifications, with no considerations given to factors such as race, religion, ethnic background, sexual preference, or gender identity.”

- “My office is not diverse, and I cannot address this concern until a job role opens up. Security personnel are unionized employees, and no roles have become available during my tenure.”

- “This is a centralized HR issue and subject to the state’s collective bargaining agreement.”

Action insights

Based on these findings, state CISOs can consider the following courses of action.

- Work to boost team’s competencies through training and education. With new threats constantly emerging, it is critical that people stay current on the latest technologies and potential threat vectors.

- Focus on workforce skills and diversity of experience. With cyberattacks originating from an ever-widening array of threats, it is ever more important that those keeping watch include skilled professionals with up-to-date capabilities and a variety of experiences and backgrounds.35

- Aim for visibility among and within contractors. Leaders should be confident in the security practices of their contractors including general IT contractors with administrator privileges. CISOs should confirm that there is adequate training and oversight of contractors who are allowed access to the state network.

- Continue efforts to work with local governments and public higher education. States share data with local government and public higher education in a variety of ways—for example, a county may administer a state’s child welfare program. This means that there are shared data vulnerabilities, and surveyed CISOs expressed particularly low confidence in these external but related organizations to keep data secure. Continued outreach, including to higher education and the private sector, can promote good practices and be instrumental in protecting public data.

Appendix 1

The 2024 Deloitte-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study uses survey responses from:36

Enterprise-level CISOs who answered 60 questions designed to characterize the enterprise-level strategy, governance, and operation of security programs. Participation was high: 50 states and the District of Columbia responded. Figure 25 illustrates the CISO participants’ demographic profile and that of their states.

For better readability, we have included relevant and select responses in the charts. Hence, the percentage totals may not equal to 100%.

The survey gave respondents the opportunity to add additional comments when they wanted to further explain an “N/A” or “other” response. A number of participants provided such comments, offering further insight into the analysis.

Appendix 2: Additional survey analysis deep dives

We want to hear

from you!

Complete a brief survey to provide your views on thought leadership content.