Managing data ethics A process-based approach for CDOs

21 minute read

07 February 2019

There’s nothing easy about data ethics in an age where virtually everything we do leaves a data trail. But to curb the potential for harm—and harness data’s power for good—government CDOs must step up to the challenge.

The proliferation of strategies for leveraging data in government is driven in large part by a desire to enhance efficiency, build civic trust, and create social value. Increasingly, however, this potential is shadowed by a recognition that new technologies and data strategies also imply a novel set of risks. If not approached carefully, innovative approaches to leveraging data can easily cause harm to individuals and communities and undermine trust in public institutions. Many of these challenges are framed as familiar ethical concepts, but the novel dynamics through which these challenges manifest themselves are much less familiar. They demand a deep and constant ethical engagement that will be challenging for many chief data officers (CDOs).

To manage these risks and the ethical obligations they imply, CDOs should work on developing institutional practices for continual learning and interaction with external experts. A process-oriented approach toward data ethics is well suited for data enthusiasts with limited resources in the fast-changing world of new technologies. Prioritizing flexibility over fixed solutions and collaboration over closed processes could lower the risk of ethical guidelines and safeguards missing their mark by providing false confidence or going out-of-date.

Learn More

Read the full CDO Playbook

Create a custom PDF

Learn more about the Beeck Center

Subscribe to receive public sector content

The old, the new, and the ugly

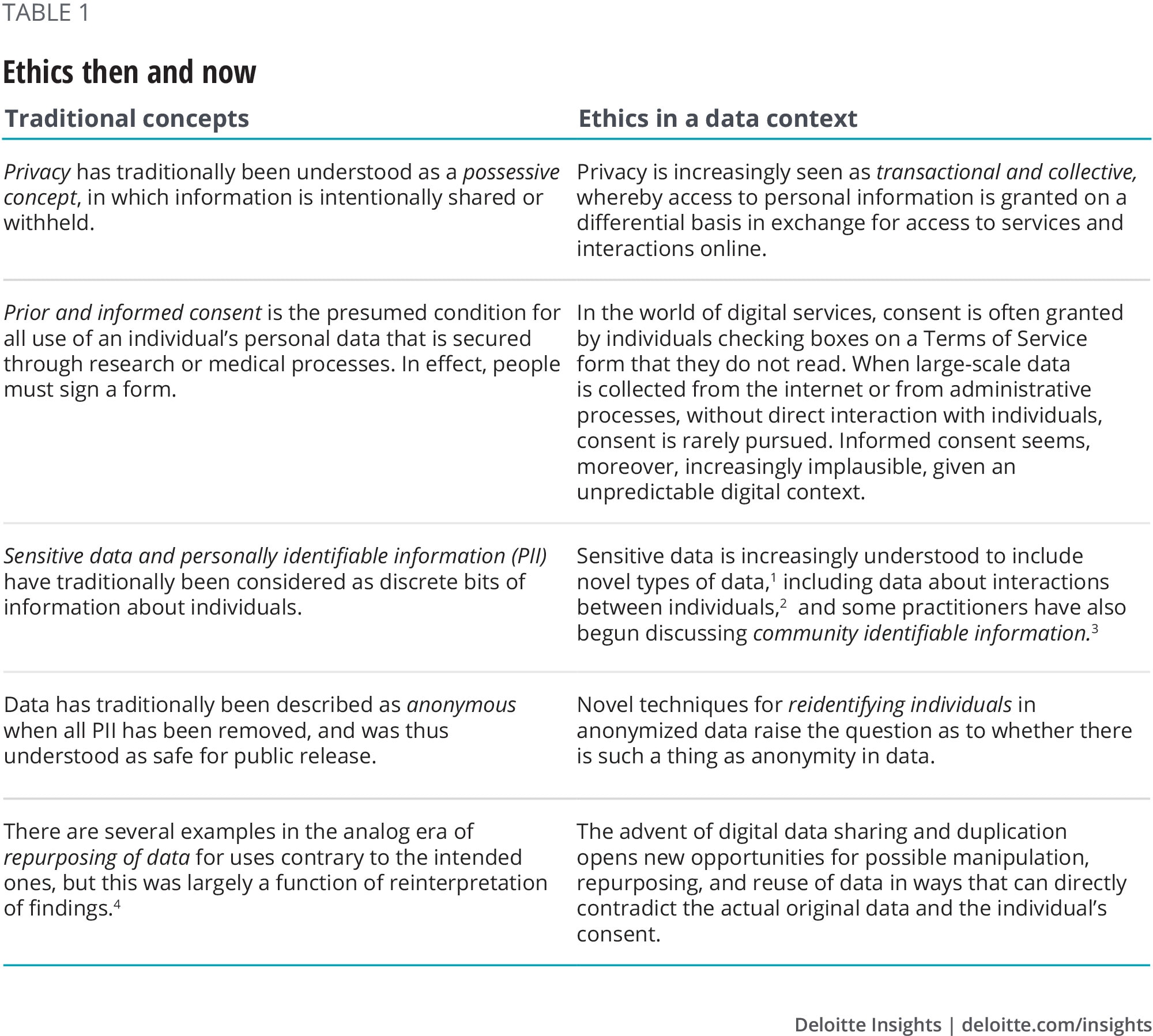

To a casual observer, many ethical debates about data might sound familiar. One doesn’t have to engage deeply, however, before it becomes clear that contemporary informatics have radically reshaped the way we think about traditional concepts (table 1).

Privacy is an excellent example. Following revelations on the controversial use of personal social media data for political campaign efforts, privacy has come to dominate popular debate about social and political communication online. This has highlighted the ease with which personal data can be collected, used, shared, and even sold without individuals’ knowledge. It also has reinforced the popular claim that digital privacy applies not only to the content of messages and personal information, but to metadata on when, how, and with whom individuals interact.

This kind of data is common to all kinds of digital interactions. Digital traces are created any time a person logs into a government website, receives a digital service, or answers a survey on their phone. These interactions need not involve users explicitly supplying information, but data about the interaction itself is logged and can be traced back to users. Often these interactions are premised with some kind of agreement to provide that data, but recent controversies illustrate just how tenuous that permission often is, and just how important people feel it is to exercise control over any type of data in which they are reflected.

These dynamics recall the concept of consent. Classically understood in terms of academic and scientific research on human subjects, the idea of consent has taken a distinct turn in the context of social media and interactions online. Not only is consent often more implied than given, the potential for informed consent is complicated by the fact that it has become virtually impossible to anticipate all the ways in which personal information can be used, shared, and compromised. Instant duplication and sharing are some of the greatest strengths data offers to government innovation, but these advantages also completely undermine the presumption that it is possible to control how data might be used, or by whom. The internet never forgets, yet from a data protection perspective, it is also wildly unpredictable.

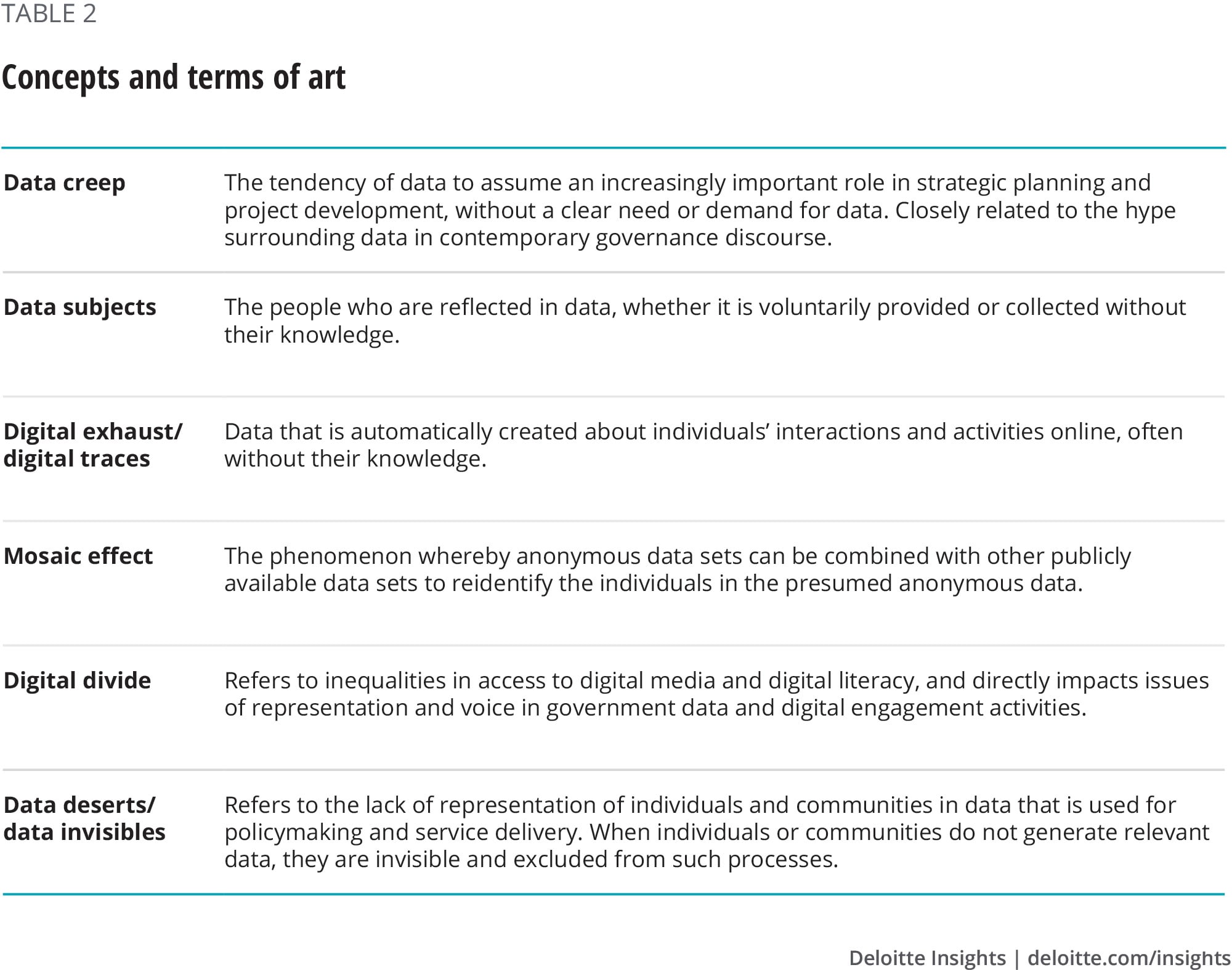

We might put trust in government security protocols to protect sensitive data, but even in the most stable of democratic contexts, we can never be entirely certain of what political agendas will look like a decade from now. Even when they do remain stable, however, technology can throw a wrench into future-proofing data. Consider the mosaic effect, the phenomenon whereby it is possible to identify individuals in an anonymized data set by combining that data with external data sets. The trouble with this phenomenon is that it is never possible to know how advanced technologies for reidentification will become—they are consistently surprising experts with their effectiveness.5 Thus, it is never possible to determine how much de-identification is sufficient to protect data subjects. Even without such capacities or access to multiple data sets, recent events highlight how easy it is to identify individuals in deidentified data sets on the basis of public information about singular events.6 There really no longer is any such thing as completely anonymous data.

These are profound complications to familiar ethical challenges, but digital data poses entirely new challenges as well, and at least two types of potential harm deserve mention for being central to democratic processes.

Firstly, datafied government processes have the potential to cause procedural harm. Data-driven and evidence-based policy is often heralded as an inherent good by many commentators. But data-driven policy is only as good as the data that drives it, and if technical capacities in government agencies are sub-optimal, poor data accuracy and reliability can produce worse policy than would have been created otherwise. The ideologies that underpin data-driven processes can also end up privileging certain social groups over others. For example, some commentators have noted how an economic rationale for innovation could inevitably privilege those who contribute most to economic activity, at the expense of the poor or economically marginalized.7

The collection of data can itself also have a deleterious effect on communities and be perceived as exploitative when data collection is not accompanied by visible benefits to those communities. This has led several groups, and indigenous communities in particular, to pursue guidelines for ensuring responsible data collection processes and interactions.8 There are common threads to these guidelines, having to do with meaningful engagement and participation, but they also display a profound diversity, suggesting that any government effort to collect data on vulnerable groups will require a thoughtful allocation of time and resources to avoid getting it wrong.

Secondly, and closely related to procedural harms, data-driven government processes can lead to preferential harms by over- or underrepresenting specific groups. This is most easily considered in terms of the “digital divide.” Individuals with access to the internet and with technological literacy will be most likely to participate in participatory processes or to be represented in digitally curated data, which can result in prioritizing the voice and representation of groups that are already well represented.9 “Data deserts” and “data invisibles” are terms that have been coined to understand how some groups are not represented in the data used to develop government policy and services.10 In extreme cases, institutional constraints and limited information mean that this can effectively exclude consideration of the interests of vulnerable groups from consideration in government processes.

Procedural and preferential harms are especially difficult to anticipate given the institutional tendency toward data creep, whereby an interest in technology’s potential may drive the adoption of data and technology to be pursued as an end in itself. When data is itself presumed to be a selling point, or when projects aspire to collect and manage maximum amounts of data without clear use cases, it can be hard to spot and mitigate the kinds of ethical risks described above.

Much has been written about the novel ethical challenges and risks posed by contemporary technology and data strategies. A number of taxonomies for harm have been created in the contexts of government work, private sector activities, smart cities, and international development.11 At the end of the day, however, the list of things that can go wrong is as long and diverse as the contexts in which data can be leveraged for social good. Context is indeed king. And for data enthusiasts in government, no context is typically more important or unique than the institutional context in which these strategies are developed.

Ethics in an institutional context

Government use of data and technology is often divided into “front office” and “back office” activities. It can be tempting to consider ethics as most relevant to the former, where there are direct interactions with citizens and an opportunity to proactively engage on ethical issues. This would be a mistake, however. Even when data is collected without any direct interaction with citizens, there are important questions to be asked about consent and representation. Apparently anodyne methodological issues having to do with data validity and harmonization can have ethical consequences just as profound as processes related to data collection, data security, or open data publication. Perhaps most importantly, it is worth recalling that unforeseen challenges, whether related to anonymity, reuse, or perceptions of representation, can impact the public’s trust in government, and aggrieved citizens are unlikely to make nuanced distinctions between back- and front-office processes.

Data ethics should be considered across governmental institutional processes and across different types of data, whether they target government efficiency or civic engagement. The most useful heuristic may be that ethical questions should be considered for every process in which data plays a role. And data plays a role in almost all contemporary projects.

Once it is clear whether or not an activity or policy development process has a data component, it is important to ask questions about what ethical risks might be present, and how to address them. In particular, there are several inflection points at which ethical vulnerabilities are most profound. These are listed in the sidebar “Common points of vulnerability in project cycles,” together with examples of the types of questions that can be asked to identify ethical risks at various stages.

Common points of vulnerability in project cycles and questions to consider

- Project planning and design

Does the project collect the right data and the right amount of data? What are the ethical implications? What are the most immediate risks and who are the most important stakeholders? What resources are needed to manage data ethics? What are the opportunities for engaging with experts and the public along the way? How can the data ethics strategy be documented? What are the most important points of vulnerability? What data protection strategies and controls to deploy in case of a breach?

Note that organizations can employ a “privacy-by-design” strategy to comprehensively address vulnerabilities across the project life cycle. This approach aims to protect privacy by incorporating it upfront in the design of technologies, processes, and infrastructure. It can help restrict the collection of personal data, enable stricter data encryption processes, anonymize personal data, and address data expiry.

- Data collection and consent

Who owns data? Who should give permissions and consent? How will the act of data collection affect the people it is collected from and their relationship to the government? Is more data being collected than necessary? Is the data secure during collection? Are there any methodological issues that affect the reliability of the data? Would the data collected be seen as valid by the people it is collected from? How to procure consent for alternate use of the same data?

- Data maintenance

Who has access to the data? Does the level of data security match the potential threats to the data? Is there a timeline for how long data will be maintained and when it will be destroyed? What are the specific guidelines around data portability? Which formats and structures are used to share data with the data subjects, other data controllers, and trusted third-party vendors?

- Data analysis

Does the data have any biases or gaps? Does other information exist that would contradict the data or the conclusions being drawn? Are there opportunities to involve data subjects in the analysis? How can you avoid inherent algorithmic bias in the data analysis?

- Data sharing and publication

Is an appropriate license selected for open data? Does the data contain sensitive information? Have all potential threats and harms from releasing or publishing the data been identified? Are there explicit ethical standards in data-sharing agreements?

- Data use, reuse, and destruction

What were the ethical issues surrounding how the data was originally collected? Has the context changed since then in a way that requires regaining consent of data subjects? Are there data ownership or licensing issues to be aware of? What methods are used for secure data destruction?

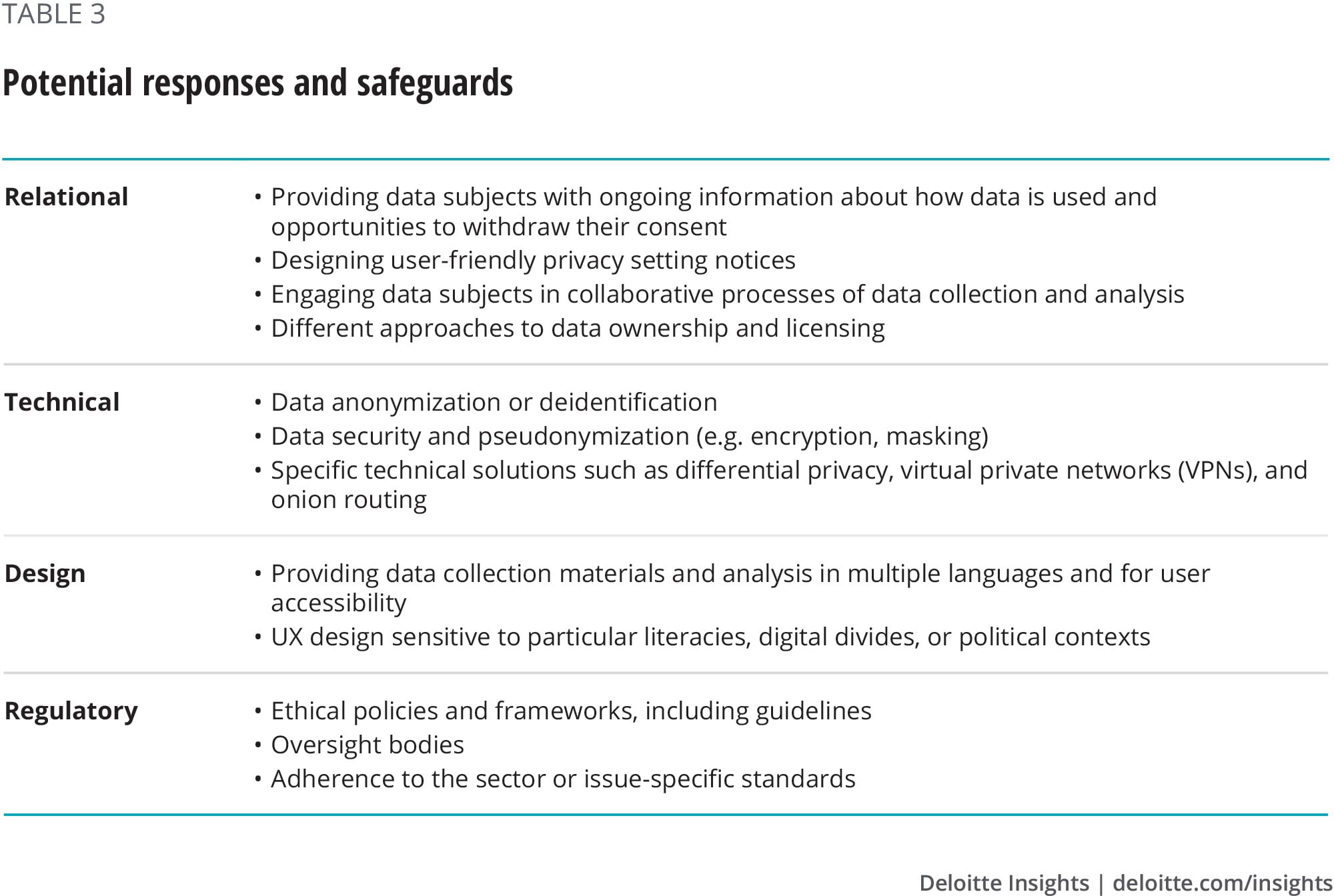

These are some key points in projects and processes where asking questions about ethics can be most effective. These questions should focus on potential risks and are likely most effective when pursued by groups and in conversation. When potential risks have been identified, there are many types of potential responses, some of which are listed in table 3.

It should be noted that any response or ethics strategy could further exacerbate ethical challenges by installing a false sense of security. It is very easy for civil servants to overestimate the security measures taken to protect personal data when their technical capacities are limited or when they do not have a full overview of the vulnerabilities and threats that might be posed to that data or the individuals reflected in it.

Chief data officers and information officers likely have an advantage in this regard but will likely also struggle to keep up to date on all cutting-edge data ethics issues. This is an inevitable challenge for people working to advance innovative use of data inside of government, where demands are often high and resources low.

It is also worth noting that the danger of false security can be just as important for policy responses as it is for technical responses. It might be easy to create a consent policy for digital service delivery that would check internal boxes and satisfy internal project managers, but eventually could lead to resentment and anger from communities that did not understand how the data would be used or shared. The danger that ethical regulatory measures will produce a false sense of security has on occasion been blamed on poor “hard” technical capacities.12 However, the “soft” capacities required to assess ethical risks, conduct threat assessments, and anticipate how specific constituencies will experience data-driven processes are typically just as important, and can be just as challenging for civil servants to secure.

In addition to capacity constraints, the use of data in government is often subjected to a host of other limitations, including resource constraints, institutional cultures, and regulatory frameworks. Each of these poses unique challenges to managing ethical risks. Resource constraints are perhaps the most obvious, as community consultations, developing tiered permission structures for data, and even SSL certificates all cost money and time. Some of the more novel and aggressive approaches to managing ethical risks might clash with political priorities or cultures for short-term outputs. Regulations such as the Paperwork Reduction Act are notorious for the impediments they pose for proactive engagement with the public.13

These challenges will manifest differently for different types of projects and in different contexts. Some will require deep familiarity of differential privacy models or the UX implications of 4G penetration in specific geographic areas. Others will require deep expertise in survey design or facilitation in multiple languages. Nearly all will likely require close and thoughtful deliberation to determine what the ethical risks are and how best to manage them. The ethical challenges surrounding innovative data use are generally never as straightforward as they first appear to be. It’s simply not possible for any one person or team to be an expert in all of the areas demanded by responsible data management. Developing cultures and processes for continual learning and adaptation is key.

Recommendations for CDOs: A process-focused response

Ethically motivated CDOs could find themselves in a uniquely challenging situation. The dynamic nature of data and technology means that it is nearly impossible to anticipate what kinds of resources and expertise will be needed to meet the ethical challenges posed by data-driven projects before one actually engages deeply with them. Even if it were possible to anticipate this, however, the limitations imposed by most government institutions would make it difficult to secure all the resources and expertise necessary, and the fundamentally ambiguous nature of ethical dilemmas makes it difficult to prioritize data ethics management over daily work.

Progressively assessing and meeting these challenges require a degree of flexibility that might not come naturally to all institutional contexts. But there are a few strategies that can help.

Prioritize processes, not solutions

Whenever possible, CDOs should establish flexible systems for assessing and engaging with the ethical challenges that surround data-driven projects. Identifying a group of people within and across teams that are ready to reflect on these issues and are willing to be on standby for discussions can greatly enhance the efficiency of discussions. Setting up open invitations at the milestones and inflection points for every project or activity that has a data component (see sidebar, “Networks and resources for managing data ethics”) can facilitate constant attention. Also, it allows the project team to step back and explore ways to embed privacy principles in the early design stages. Keeping these discussions open and informal can help create the sense of dedication and flexibility often necessary to tackle complex challenges in contexts with limited resources. Keeping them regular can help instill an institutional culture of being thoughtful about data ethics.

Networks and resources for managing data ethics

There are several nonprofit, private-sector, and research-focused communities and events that can be useful for government CDOs. The Responsible Data website curates an active discussion list on a broad range of technology ethics issues.14 The International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) manages a community list serve,15 and the conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency in Machine Learning convenes academics and practitioners annually.16

Past activities and consultations like the UK government’s public dialogue on the ethics of data in government can also provide useful information,17 and has resulted in the adoption of a governmentwide data ethics framework, which includes a workbook and guiding questions for addressing ethical issues.18 Responding to the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) regulations, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has set up a new project committee to develop guidelines to embed privacy into the design stages of a product or service.19

Several other useful tools and frameworks have been produced. The Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT) has developed a Digital Decisions Tool to help ethical decision-making into the design of algorithms.20 The Utrecht Data School has developed a tool, data ethics decision aid (DEDA) that is currently being implemented by various municipalities in the Netherlands.21 The Michigan Department of Transportation has produced a decision-support tool dealing with privacy concerns surrounding intelligent transportation systems,22 and the IAPP provides a platform for managing digital consent processes.23 The Sunlight Foundation has developed a set of tools to help city governments ensure that open data projects map community data needs.24

Many organizations also offer trainings and capacity development, including the IAPP,25 journalism and nonprofit groups like the O’Reilly Group,26 and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which offers trainings on specific activities such as conducting privacy threat assessments.27

Several white papers and reports also offer a general overview of issues and approaches, including the European Public Sector Information Platform’s report on ethical and responsible use of open government data28 and Tilburg University’s report on operationalizing public sector data ethics.29

This list is not exhaustive, but it does illustrate the breadth of available resources, and might provide a useful starting point for learning more. Participants in the MERL Tech Conference on technology for monitoring, evaluation, research, and learning also maintain a hackpad with comparable networks and resources for managing data ethics in the international development sector.30

In some contexts, it might make sense to formalize processes, creating bodies similar to the NYC task force mandated to assess equity, fairness, and accountability in how the city deploys algorithms. In other contexts, it may make more sense to consider alternative formats like data ethics lunches or short 30-minute brainstorming sessions immediately following standing meetings and try to get everybody on the same page about this being an effort to build and sustain meaningful trust between constituents and government.

Flexibility can be key to making this kind of engagement effective, but it’s also important to be prepared. For each project, consider identifying a key set of issues or groups that are worth extra attention, and prioritize getting more than two people into discussion regularly. Group conversations can help surface creative solutions and different points of view, and having them early can help prevent unpleasant surprises.

Engage with experts outside the box

A process-based approach to managing data ethics will only be effective if teams have the capacity to address the risks that are identified, and this will rarely be the case in resource-strapped government institutions. CDOs should invest in cultivating a broad familiarity with discourses on data ethics and responsible data and the experts and communities that drive those discourses. Doing so can help build the capacity of the teams and stakeholders inside government and also support innovative approaches to solving specific ethical challenges through collaboration.

Many sources of information and expertise are available for managing data ethics. Research communities regularly publish relevant reports and white papers. Government networks discuss the pros and cons of different policy options. Civil society networks advance cutting-edge thinking around data ethics and sometimes provide direct support to government actors. Increasingly, private sector organizations, funders, consultants, and technology-driven companies are also offering resources.

Becoming familiar with these communities is a first step; just subscribing to a few RSS feeds can provide prompts every day, flagging issues that need attention and honing it to keep ethical challenges from slipping through the cracks. Cultivating relationships with experts and advocates can provide important resources during crises. Attending conferences and events can provide a host of insights and contacts in this area.

Open up internal ethical processes

Perhaps most importantly, process-focused approaches to managing data ethics should be open about their processes. Though some government information will need to be kept private for security reasons, CDOs should encourage discussions about keeping the management of ethics open and transparent whenever possible. This adheres to an important emerging norm regarding open government, but it’s also critical for making data ethics strategies effective.

Open source digital security systems provide an illustrative example. A number of services are available for encrypting communications, but digital security experts recommend using open source digital security software because its source code is consistently audited and reviewed by an army of passionate technologists who are vigilant to vulnerabilities or flaws. As it is not possible to audit closed source encryption tools in the same way, it is not possible to know when and to what degree the security of those tools has been compromised.

In much the same way, government data programs may be working to keep information or personal data secure and private, but by having open discussions about how to do so, they typically build trust with the communities they are trying to serve. They also open up the possibility of input and corrections that can improve data ethics strategies in the long and short run.

This kind of openness could involve describing processes in op-eds, blog posts, or event presentations or inviting the occasional expert to data ethics lunches or the other flexible activities described above. Or it might involve the publication of documents, regular interaction with the press, or a more structured way of engaging with the communities that are likely to be affected by data ethics. Whatever the mechanism or the particular constraints on CDOs, a default inclination toward open processes will contribute toward building trust and creating effective data ethics strategies.

Navigating the trade-off between rigor and efficiency

Data is hard. So are ethics. There is nothing easy about their interface either, and CDOs operate in a particularly challenging environment. This article has not provided any out-of-the-box answers to those challenges, because there are none. A proactive and meaningful approach to data ethics will typically involve compromises in efficiency and effectiveness. Ethical behavior isn’t easy and civic trust in a datafied society isn’t free. Being attuned to the ethical challenges surrounding government data means that CDOs and other government data enthusiasts will necessarily be faced with trade-offs between data ethics rigor and efficiency—between the perfect and the good. When that time comes, it’s important to have realistic expectations about the cost of strong ethics, the risks of getting it wrong, and the wealth of options and resources for trying hard to get it right. A careful and informed balancing of these trade-offs can increase CDOs’ chances of managing data ethics in a way that helps build trust in government and hopefully avoids disaster following the most innovative applications of data in governance.

Enabling strong data governance and ethical use of data

This article focuses on improving data ethics through process changes and improvements. However, it needs to be acknowledged that although the process-based approach is important and sometimes a critical first step, it’s not the only way to achieve privacy protection outcomes. There are also a host of technologies, strategies, and solutions that can enable strong data governance and ethical use of data.

- Data discovery, mapping, and inventorying solutions: These solutions can help you to understand data across organizational silos, map the data journey from the point of collection to other systems (both internal and external), and determine the data format and validity in the system.31

- Consent and cookie management solutions: There are many software-as-a-service (SaaS) solutions that can manage your website’s user consents. These services typically manage your website’s cookies, automatically detect all tracking technologies on your website, and provide full transparency to both the organization and the user.32

- Individual rights management solutions: This is a subset of digital rights management technologies that provide users the right to access, use, reuse, move, and destroy their data.33

- Data protection impact assessment (DPIA): An organization can conduct an extensive impact assessment of its data, systems, and other digital assets to identify, assess, and mitigate future privacy risks. These assessments can help organizations understand their technical capacities and evolve appropriate organizational measures around privacy.34

- Incident management solutions: These solutions help an organization to identify, analyze, quarantine, and mitigate threats to avoid future recurrences. Such software solutions can help restrict threats from becoming full-blown attacks or breaches.

Toward that end, this article aims to provide a brief discussion on why data ethics is such a challenging and important phenomenon, and to offer some entry points for informed, critical, and consistent ways of addressing them. The hard work of actually pursuing that challenge falls on the CDO.