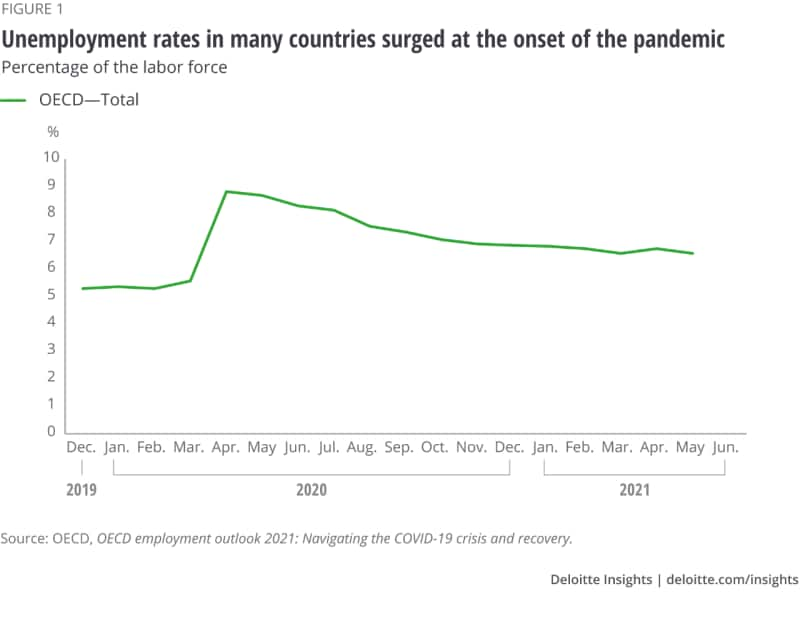

This relatively rosy unemployment picture is hiding a great deal of turmoil. The recovery this time doesn’t seem to be following traditional patterns. The global decline in labor force participation rates is one troubling signal. Meanwhile, many workers are switching jobs, seeking higher pay or more flexibility.9 About 41% of employees globally are considering quitting in the next year, according to a 2021 survey of more than 30,000 employees.10 While many may be moving to greener pastures, employee stress and burnout may be contributing to what some have called the “great resignation.”

To function effectively in this fluid environment and endure future shocks, economies need adaptive workforces. Unfortunately, many government workforce policies have been based on an industrial-era model of employment. Work is changing at a dizzying pace and labor policies need to keep up.

Trend drivers

Governments face multiple pressures to develop workforce resilience:

- The pandemic and its enduring impact on the labor market.

- A rapidly changing technological landscape, with automation, AI, and digital technologies disrupting workers and industry alike.

- A growing need for an adaptable, resilient workforceto enable the economy to quickly react to rapid shocks.

Trend in action

Many jobs lost during the pandemic are not expected to come back. Researchers at the University of Chicago project that 32–42% of COVID-19–induced layoffs will be permanent.11 This means that despite a strong labor market, some workers will need to learn new skills for new careers.

Many governments are enacting policies that equip people to adapt not only to new jobs, but to entirely different fields. Six adaptive workforce shifts identified are:

- Shift 1: Government’s role in promoting alternative credentialing

- Shift 2: Job-centric upskilling

- Shift 3: Governments playing matchmaker

- Shift 4: Redefining employment for gig workers

- Shift 5: Infrastructure support to enable an adaptive workforce

- Shift 6: Adapting to the changing nature of higher education

Shift 1: Government’s role in promoting alternative credentialing

Alternative credentialing can encourage reskilling amid rapidly evolving technology.12

The shrinking shelf-life of digital skills requires continuous reskilling. Employers desire tracking and verification of those skills. As a result, the job market increasingly calls on training providers and academic institutions to offer “credentialized” records of learning and mastery.13

Rather than relying heavily on two- and four-year degrees, skill-specific microcredentials, digital badges, or certificates specify the exact technologies an applicant has mastered. This simplifies career shifts and employee selection, making labor markets more efficient.

The New Zealand government’s policies acknowledge alternative credentials. The New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA), a government agency, aims to deliver a unified vocational education system that will bring together industry, Māori groups, and educators. The process invites industry to work with higher education to develop microcredentials,14 which are reviewed to ensure quality standards.15 As of January 2022, there were 203 NZQA-approved microcredentials.16 For example, forestry operations—environment was a microcredential developed for building practical skills in forestry; 65 learners were awarded the microcredential within the first year of introduction in FY19–20.17

In March 2021, the Ontario government in Canada expanded the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP) to include more than 600 microcredential programs, making those programs feasible for students on financial support. The 2021 provincial budget includes an additional CAD 2 million to develop a virtual skills passport.18 The passport will track learners’ credentials and let them share credentials digitally with prospective employers. Similar efforts are also being undertaken in Australia, Europe, and parts of the United States.19

Shift 2: Job-centric upskilling

Even before the pandemic, many sectors faced a skills gap. Traditional job training programs, however, often struggled to fill the gap.20

Governments are embracing a job-centric upskilling model. Job-centric upskilling focuses on capabilities for specific, in-demand jobs. Industry contributes suggestions for training, and in many cases, offers on-the-job-support to workers. Results are measured not merely by job placement, but by success in the job. For example, through a public-private partnership called “Back to Work RI,” the state of Rhode Island provides targeted skills training and support services to displaced workers, ushering them into growing sectors such as health care and information technology.21

Job-centric upskilling can be especially important for workers with limited job skills or those going through life challenges that make professional success difficult. The Hospitality Workers Training Center (HWTC) in Toronto found that the personal needs of its participants varied widely, ranging from child care, to housing and food security, to substance abuse counseling, to transportation. To help participants overcome these hurdles, the HWTC performs an extensive assessment of participant needs upfront. After participants’ training, a job coach assesses their post-training needs and works with employers to address performance issues that may impact job retention. This program, funded by the government of Canada, has improved its participants’ job prospects. About 80% of HWTC’s participants get employed in Toronto’s hospitality industry within eight weeks of training.22

Shift 3: Governments playing matchmaker

Governments are creating online talent platforms to help businesses find the skills they need. Online matchmaker platforms can introduce jobseekers to the educational requirements of their desired careers, identify training opportunities, and establish contacts with employers.

India’s National Career Service (NCS) is a job search and matching initiative launched by the Ministry of Labor and Employment that aims to provide end-to-end employment-related services to workers. Through the NCS digital centralized portal, a wide range of career-related services including job search, job matching, rich career content, career counselling, and information on job fairs are provided. This portal brings together job seekers, employers, skill providers, career counsellors, government departments, and other stakeholders under one roof.23

Similarly, in Australia, the Tasmanian Government’s Rapid Response Skills Matching Service was developed to support Tasmanians whose positions were affected by the pandemic and to simplify access to reemployment funds. The Skills Matching Service is an easy way for employers to identify the right person for a vacancy. Between March and December 2020, it facilitated the introduction of nearly 600 Tasmanian job seekers to their next career opportunity.24

Governments are also trying to expand the universe of people welcome in the labor market. For instance, in the United Kingdom, there are 7 million working-age people with a disability or long-term health condition, but only a little over half of them hold jobs. According to the 2021 UK Disability Survey, 56% of people with disabilities wanted more support in finding a job.25 The Department for Work & Pensions (DWP) collaborates with the National Autistic Society to adapt DWP’s “Jobcentre Plus” sites to accommodate job seekers on the autism spectrum. Additionally, more than 26,000 work coaches at these sites undergo specialist accessibility training to better understand disabled clients.26

Shift 4: Redefining employment for gig workers

COVID-19 not only highlighted the value of gig workers but also the risks they face every day. Many governments are considering new policies to patch holes in the safety net, which gig workers once used to fall through. In the United States, a new federal program, Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, provided unemployment benefits to independent workers. Gig workers, including drivers, technology contractors, and house cleaners—who were traditionally ineligible for unemployment benefits—collected benefits during the worst of the pandemic.27

The European Union launched a public consultation with trade unions and other employers on the need to improve long-term working conditions for gig workers. In the first stage of consultation, it identified seven areas where action is needed. Some of these include employment status, working conditions, access to social protection, and bargaining. In June 2021, it launched the second stage of consultation to identify actions to take in each area.28 A similar effort began in New Zealand, which formed a tripartite working group between the government, business, and the Council of Trade Unions to improve work conditions for contractors. Options under consideration include steps to deter misclassification of employees as contractors and enhance the protection of contractors who are not classified as employees.29

Shift 5: Infrastructure support to enable an adaptive workforce

As the workforce continues to adapt to a digital world, governments are increasingly focused on providing workers and companies access to broadband, which helps working-age adults access education, work remotely, and find employment.

The United Kingdom’s Project Gigabit, for example, is a £5 billion government infrastructure project that aims to deliver fast and reliable digital connectivity to the entire country.30 In the United States, the infrastructure law enacted in November 2021 includes US$65 billion to expand broadband access.31

Shift 6: Adapting to the changing nature of higher education

The explosion of digital technology, automation, and changes in the nature of work are prompting many universities to rethink their mission.

According to a 2020 World Economic Forum report, employers believe the following competencies will be most in demand by 2025: critical thinking; analytical skills; problem-solving; and skills related to self-management, such as active learning, resilience, stress tolerance, and flexibility.32 However, very few education programs explicitly include developing these competencies in their curricula.33 The report also indicates that employers estimate they will need 40% of their employees to learn new skills in the next six months.34

Some governments are playing a major role in transforming higher education to meet these demands. The National University of Singapore (NUS) launched the School of Continuing and Lifelong Education in 2015 to expand its offerings for working adults. This includes part-time degrees, modular certificate courses, executive development programs, and even free classes for NUS alumni wishing to keep their skills sharp.35 Similar continuing education training centers have been launched across other institutes of higher learning in Singapore.36