Rx CX has been saved

Rx CX Customer experience as a prescription for improving government performance

What could happen if government viewed certain public sector challenges through the lens of customer experience? By changing the way people interact with a process rather than focusing solely on the process itself, agencies can broaden the range of available solutions.

Introduction

When rail operator Eurostar sought to improve the journey between London and Paris for its customers, it turned to a group of engineers. The engineers focused on how to improve operations and concluded the best way to make the journey better was to shorten it. So Eurostar spent £6 billion on new tracks that shaved about 40 minutes from what had been a three-and-a-half-hour journey.

But what if Eurostar changed the customer experience rather than the infrastructure?

In a TED talk, ad guru Rory Sutherland reframed the problem:

Why is it necessary to spend £6 billion speeding up the Eurostar train when, for about 10 percent of that money, you could have top supermodels, male and female, serving free Chateau Petrus to all the passengers for the entire duration of the journey? You’d still have £5 billion left in change, and people would ask for the trains to be slowed down.1

It’s a simple but profound idea. By focusing on the customer experience (CX), rather than simply optimizing an existing business process, you widen the range of solutions available to tackle any given problem, often at a far lower cost.

What could this shift in focus mean for the public sector?

Learn More

View the Customer Experience in Government collection

Explore the interactive case studies

The customer experience lens: A new approach to problem solving

Consider the problem of reducing the cost of doing business in regulated industries, to help make the United States a more attractive place to do business. Public sector red tape generates many costs: paperwork, attorneys’ fees, extra equipment, endless training seminars, wasted executive time, and fees for the armies of consultants who provide advice on compliance.

The traditional response is almost always the same: Reduce the number of regulations on the books. The typical problem with this approach is that the political will to do so is almost never in adequate supply. The problem never gets solved.

Viewed through the lens of CX, the problem looks different. While most businesses would welcome lighter regulation, what is really important to them is lowering the burden of compliance. By focusing on clarifying rules, simplifying interactions, and cutting turnaround times, a solution to a seemingly intractable problem becomes more achievable.2

This approach applies to a host of other areas. Take the problem of improper government benefit payments, which costs the federal government $137 billion annually.3 On the surface, it may seem like a problem warranting improved fraud-detection capabilities and greater enforcement. And in some cases it is. But in other cases, the CX lens reveals a more nuanced picture.

A large portion of fraudulent claims are not the result of identity theft or “hard” fraud, but rather of small fibs such as “I was laid off, not fired,” or “I’m actively looking for work.” The traditional “pay-and-chase” approach of pursuing low-level fraud to recover funds after the fact is expensive and resource-intensive. A customer-centric solution, based on an understanding of who claimants are and why they do what they do, can nudge them toward more honest behavior and preempt improper payments in a more economical and sustainable way (see the sidebar “CX and behavioral economics”).

Or consider another chronic problem facing many government agencies: attracting and retaining the best and brightest talent. What may appear to be an issue fixable only through better salaries and benefits may actually have more to do with the hiring experience. Knowing your candidates and how they learned about the job is critical, and viewing the employee experience through the lens of CX can help reframe traditional notions of marketing, screening, and interviewing. For example, in its search for candidates with software coding expertise, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau advertised a fellowship in a place only coders would look—the source code of its website. This exercise helped identify curious and skilled technologists.4

An agency’s ability to effectively execute its mission is linked to its ability to deliver an effective customer experience to businesses, citizens, and its own employees.

The truth of the matter is that an agency’s ability to effectively execute its mission is linked to its ability to deliver an effective customer experience to businesses, citizens, and its own employees.

CX and behavioral economics

Customer analytics and CX techniques such as customer segmentation can unlock a treasure trove of insights into customer behaviors, issues, needs, and pain points. In the commercial arena these insights inform actions on marketing spend, channel choice, pricing, advertising message, and other tools of the marketing and sales trade. But many of these actions are not relevant or not available to government agencies.

But, there are levers available beyond those of the traditional marketing department that can be utilized to activate the opportunities CX insights have identified. The field of behavioral economics suggests small, discreet actions that can yield powerful results through “nudges.”

Nudging more honest behavior in unemployment insurance programs

New Mexico used this approach to tackle the problem of small-scale fraud in unemployment insurance (UI) claims. Officials at the New Mexico Department of Workforce Solutions (DWS) recognized that a large portion of their fraudulent claims were due simply to small fibs rather than criminal intent.

Take Eric, for example. Eric was fired from his job as a line cook for repeatedly being late. When he applies for UI benefits, he’s asked whether he was fired or laid off. Eric picks the latter. Or consider Karen, a single mom who’s been laid off and has begun collecting unemployment. In her search for full-time work, Karen opts to take a temporary job at 20 hours a week until a full-time position opens up. But when she’s asked if she worked in the last week, she checks the “no” box. George lost his job when a local paper downsized. He’s tackling that novel he always wanted to write. And while he occasionally scans the job openings on Craigslist, he never really follows through. But when George is asked if he’s actively looking for work, his response is “yes.”

One traditional solution is to pursue low-level cases of fraud more vigorously, which is typically expensive and heavy-handed and may deny benefits to those who genuinely qualify. Instead of pursuing a more traditional “chase and recover” approach, however, New Mexico’s DWS opted to use behavioral economics principles to nudge claimants toward honesty through targeted interventions. Showing Eric a preloaded letter of inquiry about the circumstances surrounding Eric’s termination addressed to his ex-employer may provide just enough of a nudge to make him do the honest thing. Letting Karen know that nine out of ten people report all new income could be enough to encourage her to report hers. And asking George to commit to a specific job-search goal each week may increase his follow-through—and his chances of finding another job.

New Mexico’s use of these techniques made claimants twice as likely to report new earnings, half as likely to commit fraud, and up to 20 percent more likely to find work. By nudging its customers toward positive behavior, the agency was able to improve outcomes and deliver on its overall mission.5

Getting started with nudges

How can organizations encourage certain behaviors and nudge users to choose option A rather than B? According to the UK government’s Behavioral Insights Team, there are four basic principles to the application of behavioral nudges, summarized by the mnemonic EAST—easy, attractive, social, and timely.6

Make it easy. It’s human nature to avoid doing things that require effort, whether physical or cognitive. This hurdle can be sidestepped by reducing the effort involved with a task. Whether it’s making the desired behavior the default (such as automatic employee enrollment in an employer’s 401K plan), auto-populating information into online forms, or simply communicating in plain language, reducing the hassles of transactions can help nudge customers toward desired behaviors.

Make it attractive. If a nudge grabs our attention, we’re more likely to follow it. Images, color, positioning, and personalization all play a role in ensuring the right things catch the eye and drive behavioral change. For example, when letters sent to automobile tax offenders in the United Kingdom began including images of their vehicles, payment rates rose by nearly 10 percent.7

Make it social. Peer and social networks can be a powerful tool in the context of behavior. For example, simply showing customers that most of their peers do perform the desired behavior—paying taxes on time, conserving power usage, or recycling—can be enough to nudge them in the right direction.

Make it timely. The same request made at different times can elicit different responses. People tend to be more receptive to changing their behavior when their habits have already been disrupted, so orienting nudges around life events can be helpful. For example, in the United Kingdom, sending text message reminders to those owing court fines 10 days before collection officers were sent to their homes doubled the value of payments made.8

Harnessing customer experience to drive performance improvement

In the private sector, once-skeptical executives have come to appreciate the importance of a great customer experience to achieving superior financial performance.

A study by Watermark Consulting compared the cumulative market performance of a portfolio of leading CX companies to CX “laggards.” Between 2007 and 2015, the portfolio of CX leaders outperformed the broader market, generating a total return 35 points higher than the S&P 500 index and 90 points higher than a portfolio of the laggards.9

Additional analysis by Forrester reveals that the correlation between CX and performance holds true across most industries, except in those offering customers uniform products and a limited number of choices, such as health insurance. Even in these instances, CX leaders in health care have identified other benefits: an increase in positive behaviors such as timely submission of forms.10 This factor is particularly important for government, given its inherent challenge to encourage customer compliance with administrative requirements, while balancing customer service demands.

Until recently, CX approaches have generally been limited to improving customers’ interactions with agencies that have a “retail” function, such as mail delivery or the issuance of licenses. However, when rooted in a deep understanding of customers, CX can be a prescription for change—a toolset that can be applied to a wide range of transformation efforts. Everything from optimizing budgets and improving regulatory compliance to boosting employee engagement could benefit from a dose of CX. By widening the definition of “customer,” you widen the range of problems that CX tools can address.

CX can be a prescription for change—a toolset that can be applied to a wide range of transformation efforts.

The customer experience mind-set

There has been no shortage of initiatives aimed at improving customer service. In 2011, President Obama issued an executive order for federal agencies to streamline and improve their customer service.11 Since then, the rollout of healthcare.gov and controversies at the Internal Revenue Service and Department of Veterans Affairs have thrown the spotlight on the need for improved service delivery. The notoriety of such failures in service delivery has hardened public opinion and raised questions about the ability of government to fulfill its mission.

In response, government leaders are renewing their focus on service improvement. In 2014, the White House launched the US Digital Service with an eye toward applying technology in more effective ways to improve the delivery of government services to citizens. In the words of the US Digital Services Playbook,

We must begin digital projects by exploring and pinpointing the needs of the people who will use the service, and the ways the service will fit into their lives. Whether the users are members of the public or government employees, policymakers must include real people in their design process from the beginning. The needs of people—not constraints of government structures or silos—should inform technical and design decisions. We need to continually test the products we build with real people to keep us honest about what is important.

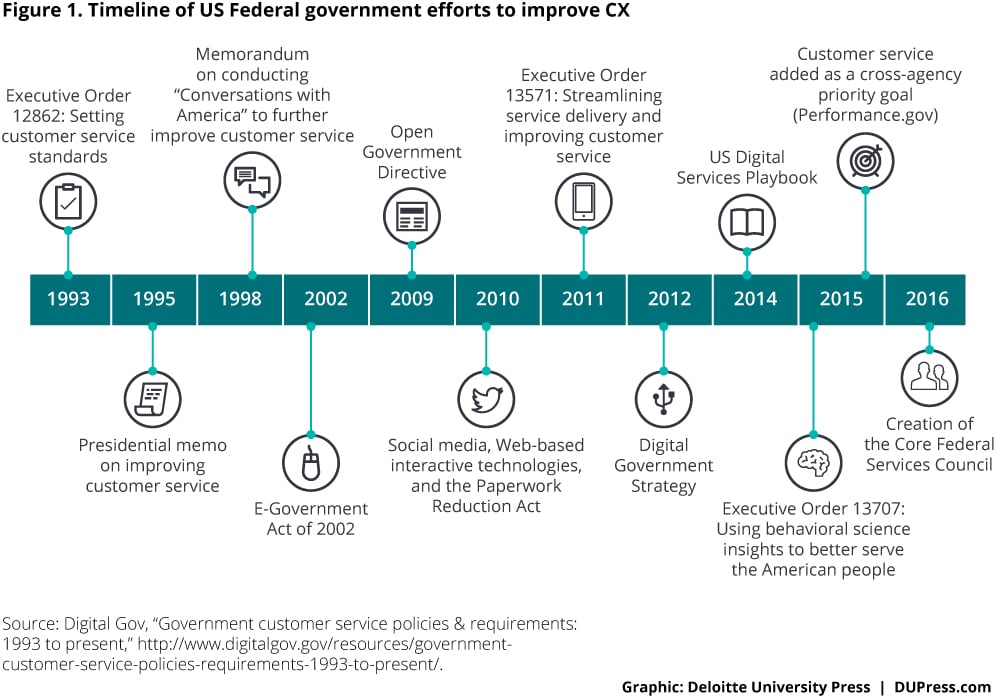

The White House also recently announced the creation of the new Core Federal Services Council, which will serve as a “government wide governance vehicle to improve the public’s experience with federal services” (see figure 1).12

But the gap between actual customer expectations and what government agencies think they deliver persists.

In a recent survey of federal managers, 65 percent indicated their organization goes above and beyond to deliver a customer experience tailored to users’ unique needs. Two-thirds said their agency’s service is on par with that of the private sector.13

But that’s not how customers see it. Consumer surveys indicate that satisfaction with government services is at an eight-year low. The federal government ranks near the bottom in a cross-industry comparison. According to the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ASCI), federal customer service rankings have declined for the third consecutive year.14 Recent Gallup poll results reinforce this view, with Americans polled continuing to name dissatisfaction with government as the nation’s second most-important problem, after the economy.15

Moving an organization beyond incrementally improving customer service to transforming customer experience entails a change in mind-set and an organizational strategy that puts the customer at the center.

What explains this dissonance?

Part of the answer lies in understanding the distinction between customer service and customer experience. The two aren’t synonymous. Customer service is one component of customer experience.

Consider a simple purchase of a book. The experience begins the moment a customer contemplates buying a book, and doesn’t end until she’s finished reading it and, if it’s really good, recommended it to her friends.

Customer service, on the other hand, is narrowly focused on the actual transaction. “Was the book in stock?” “Was the salesperson friendly?” “Was there a line at the register?”

When government agencies assess their performance by focusing primarily on their own process measures such as speed and accuracy, they risk being misled by this narrowed focus on the moment of transaction. Narrowly improving customer service isn’t enough to move the needle on customer satisfaction, which reflects the entirety of a customer’s experience.

Improving customer service requires doing things right. Improving customer experience requires this plus doing the right things and broadening the traditional definitions of which things matter. If agencies focus only on customer service, then, like Eurostar, they may wind up believing they need a faster train or more tracks and it’s unlikely that we’ll see a significant movement in public opinion about government’s ability to fulfill its mission.

Moving an organization beyond incrementally improving customer service to transforming customer experience entails a change in mind-set and an organizational strategy that puts the customer at the center (see figure 2). For government agencies this will require action on three fronts:

- Understanding your customers

- Tying CX to a specific mission outcome

- Creating a unified vision for change

We begin with a look at some leading applications of CX tools and thinking used by government organizations to understand who their customers are, how they are segmented, their beliefs, values, and behavioral triggers.

Understand your customers

Empathy is at the heart of customer experience. No amount of data on customers can replace the insights gained through experiencing firsthand what they encounter—the highs, the lows, and everything in between. Understanding the contextual, behavioral, and emotional dimensions of customers through observation is what differentiates “ethnographic research” from other methods.

Leading public and private organizations routinely use ethnographic research techniques in combination with customer segmentation analysis; social media scans; behavioral insights; customer interviews; survey data; and call center, web, and other customer interaction data to answer fundamental questions: Who are my customers? How do they behave? And what do they want?

Insights gleaned from firsthand experience can also provide a way to reach the employees responsible for delivering that experience. While it may be impractical for everyone to talk directly to customers, their unfiltered voices—recordings of call center conversations, video footage of different aspects of the experience, customer journey maps that depict the experience from the customer’s vantage point, and personas that provide a face to the data and include quotes from customer interviews—make CX real for employees in a way nothing else can.

Watch and learn: What do your customers need?

Those working on the inside of an organization may not immediately grasp the difficulties customers face, understand what their unmet needs are, or have an awareness of the informal workarounds they may have created to get something done. While focus group discussions and surveys offer valuable data on customer opinions, they don’t necessarily reveal motivations or actual behaviors.

Leading CX organizations commonly use a customer-focused method of problem solving, commonly called human-centered design, to gain a more nuanced understanding of the variety of customers they serve. Rather than requiring users to adapt their behaviors and preferences to a tool or system, a human-centered system supports existing behaviors. It involves a deep understanding of customers’ needs and experiences—both the ones they tell you about and, perhaps more importantly, the ones they don’t.

Customers contacting Amtrak call centers, for example, could get a quick cost estimate for travel on any route. Using ethnographic methods, researchers observed, however, that call center workers were jotting down the customers’ request on pen and paper and generating these estimates with a calculator. The fact that their existing platforms were unable to generate such estimates highlighted a technology gap that needed to be addressed to improve customer service, accuracy, and ease of work for employees. Uncovering behind-the-scenes situations such as this can direct you to areas in dire need of transformation. “You hear that certain areas are broken… [W]hen they say something is working well, it’s because they have workarounds that are completely counterintuitive to someone who’s actually designed a digital platform,” says Mark Waks, one of the project researchers. “But you need to see that to know what it is that’s actually broken.”16

In short, understanding the unmet needs of customers, as well as the employees who serve them, is a first step to helping improve their experiences with government.

Developing a deeper understanding of your customers involves two main activities: defining meaningful and actionable customer segments and developing a journey map that depicts common customer interactions, behaviors, and experiences across the customer’s end-to-end experience.

Define meaningful and actionable customer segments: Who are your customers?

When the sad saga of long waits and improper scheduling practices at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities in Phoenix began unfolding in spring 2014, they included allegations that as many as 63 veterans had died while waiting for appointments. While these allegations couldn’t be substantiated, it was clear that there were serious problems with scheduling backlogs and overloaded care providers within VA.17 Under the leadership of Secretary Robert McDonald, VA embarked on a journey of transformation based on understanding the customer. “The Department of Veterans Affairs is in the midst of overcoming problems involving access to healthcare. We own them, and we’re fixing them,” McDonald said. “VA’s vision for change is not only Veteran-centric, but Veteran-driven—putting our customers in control of their VA experience,” he added.18

Rather than requiring users to adapt their behaviors and preferences to a tool or system, a human-centered system supports existing behaviors.

VA spent time listening to its customers, hearing their unique stories. Through more than a hundred conversations with veterans and their families, it pieced together a rich picture of how many veterans experience services at VA.

The agency discovered that the veterans it serves often feel overwhelmed and confused when navigating the VA system and its services. Adding to their frustration was an absence of follow-up communication and acknowledgement in their interactions. Many felt it was “like speaking into a black hole.”19 They wanted to see follow-through, and welcomed a personal touch.

On the other hand, some vets reported more positive interactions with VA, and maintained that the Phoenix incidents didn’t represent their own experience.20

Different groups of veterans had different needs and behaviors. Senior vets who use VA services frequently prefer relationship-based interactions while younger vets generally want quick transactions and easy-to-use websites.21 Based on these behaviors, distinct customer personas emerged—the “fast tracker,” the “day-by-day,” the “proud patriot,” and the “unaffiliated,” among others. Personas were also developed for those who formed the support system for veterans—the “frontline provider,” the “knowledgeable buddy,” and the “family member.”

Personas help determine which issues or preferences are universal and which are specific to certain groups and how to effectively prioritize agency action. Understanding the needs and behaviors of different groups of veterans and developing distinct personas or profiles for each are helping VA decide how services should be designed for each group as the agency embarks on its journey to becoming a provider of quality medicine and first-rate health care delivered with the same proactive, real-time, courteous, coordinated service as the top-ranked customer service companies in the country.

A logical next step is understanding how each persona interacts with the system, and what the experience looks like from their perspective. That’s where journey mapping comes in.

Journey mapping: Walking in your customer’s shoes

As humans, we’re wired to pay attention to the climactic event. In a post office, it’s the moment you finally step up to the counter. In the doctor’s office, it’s actually meeting the physician after the forms, the wait, and the weigh-in. In a workforce development office, it’s when you sit across from your career counselor. But so much of what shapes a customer’s experience comes before and after the actual transaction. While a veteran may have a very positive relationship with his doctor, if he has to jump through hoops to get an appointment, or receives an erroneous bill that should never have come to him, there’s little the doctor can do to improve the overall experience.

Journey maps are designed to depict the customer’s end-to-end experience interacting with a product, service, or system, providing a unified picture of a customer’s engagement from beginning to end, when many organizations only see the sliver they work within.

In the case of the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), its current state journey map provided a picture of applicants’ touch points, common pain points, and contributing factors, supplemented with qualitative data for a better understanding of the magnitude of issues. USPTO discovered some of the issues customers were facing downstream in the examination process could be eliminated if they made some relatively simple modifications to the front-end. These would help them to focus on particular customer segments for specific issues.

The Internal Revenue Service created a future-state journey map as an anchor for what the future operations of the agency should look like. This helped employees understand where they were headed and what is needed in order to get there.

VA took a different lens, creating a journey map around life events and triggers that would likely prompt the need for services. This map helped them to anticipate needs, emotions, and contributing life factors so they could assess current services and create new ones to fill gaps.

For USPS, journey maps helped visualize its physical footprint and how customers were engaging with its retail stores. When they come in, what are they doing? Do we really need all these kiosks in all these places? Is our storefront effective—the way our customers want and need it to be?

Amtrak used journey maps to shed light on the experience that frontline staff often face and how that can affect their customers. Understanding the unmet needs of its employees and the workarounds they used enabled Amtrak to address those gaps.

There’s no one way to do a journey map—it depends on the problem you are trying to solve. But in each case they offer an anchor and a compass and serve as the jumping-off point for developing a blueprint that helps define the path forward.

Tie customer experience to a specific mission outcome

A common misconception about customer experience—one that often prevents it from being seen as a priority for cash-strapped government agencies—is that it’s only about delivering a great experience for customers and creating “moments of delight.” The fact is the same customer- centered tools and techniques can be used to advance a specific mission outcome.

As senior Forrester analyst Rick Parrish observes, “[Government] agencies all have missions they have to accomplish, and improving the experience that their customers have…helps them to accomplish those missions.”22

Take the US Transportation Security Administration’s (TSA) “PreCheck” program, for example. PreCheck allows passengers who pass a background check to speed through airport security lines. Travelers voluntarily provide data, which when combined with other layers of security, allows TSA to direct more screening resources to higher-risk passengers and deliver on its mission of protecting the nation’s transportation systems.23 The program has been expanded across 160 airports across the United States. “Expanding TSA PreCheck will enable more travelers to experience the program’s benefits while improving security and reducing checkpoint wait times,” said TSA administrator Peter Neffenger. “As more people enroll, we will be better positioned to increase overall security effectiveness and create more efficiency in the screening process.”24

Reducing costs by focusing on what matters to customers

Improving CX represents an opportunity for many organizations to reduce costs. Co-creation and customer testing, often through prototypes or storyboards, for example, help teams more clearly define what’s important to customers. Organizations can then avoid spending money on features and tools their customers will never use, or messaging that misses the mark. Early testing of new features helps give organizations a better feel for customer adoption and leads to more relevant products and services.

A better understanding of customer needs and behavior can enable government agencies to not only serve constituents more effectively but to do so in a more cost-efficient way. Take the case of call centers. While most citizens would prefer not to have to place repeated calls to agency call centers, they are often left with no other choice when they are trying to determine the status of an application, tax return, or other query. How can agencies reduce the volume of these “status-checking” calls? By serving customers completely the first time.

Many call centers are designed to keep customers away from expensive staff. A maze of complex Interactive Voice Responses (IVR), call routing, and queue management systems divert calls to the least expensive resources (online or to a lower-paid, less knowledgeable worker) with the objective of lowering costs. But often what ends up happening is exactly the opposite.

For human services agencies, for example, attempts to drive down transaction costs by redirecting calls actually increase total system costs in the long run, with multiple calls required to resolve a single issue. Think about it. Is it better to serve the customer once for $30, or five times at $15 each? For a thousand customers, that’s $30,000 versus $75,000 (assuming these callers are never directed to an expensive staff member), to say nothing of the increased customer frustration and its impact on call center staff.

Call center staff in Arizona conducted more than 20,000 interviews in June 2015, completing almost 60 percent in one touch. If 41 percent of these were unresolved and called five additional times, those are 43,050 unnecessary repeat contacts. According to Michael Wisehart, assistant director of the Division of Benefits and Medical Eligibility at Arizona’s Department of Economic Security, “The understanding of the root cause of the immense ongoing workload allowed us to redefine both our processes and outcome measures. These changes have allowed us to absorb over twice as many cases in the system, while improving services and without any additional taxpayer investment.”25

Reducing call center volume

While it may not be possible for agencies to quickly answer every single call that comes to their call centers, it is possible for them to try to optimize resource allocation by shifting routine, status-check type queries to online channels. By encouraging customers to use specific channels for different tasks (depending on nature and urgency), agencies have an opportunity to save on costs and staff time while also making the experience better for customers.

More taxpayers are going online to get tax help, and actively use digital services such as the IRS’s “Where’s My Refund?” electronic tracking tool. Taxpayers have used it more than 193 million times in 2015, surpassing the total of 187 million for all of 2014.26 In fact, overall call volume at the IRS—the number of callers attempting to reach a live assistor—dropped from 54.2 million calls in FY 2013 to 39.9 million in FY 2014.27

Ultimately, listening to customers and getting to the bottom of their issues can also help identify recurring themes and help agencies prioritize remedial action and as a result save significant dollars. When telecom company Sprint found itself bombarded with support calls and complaints from unhappy customers, it renewed its focus on understanding its customers. Conversations with customers revealed the most pressing needs and focus areas for the organization. By addressing these problems, Sprint not only increased customer satisfaction but reduced service costs by 33 percent—over $1.7 billion per year.28 For government agencies, unhappy customers mean more call center traffic and more employee time spent on resolving issues, often putting pressure on already strained budgets. Improving the customer experience can help alleviate these issues and lower costs.

Reducing improper payments

A customer-centric approach can help reduce costs incurred due to errors or improper payments. Consider the example of the US Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS). Its National School Lunch Program that provides low-cost or free meals to 30 million children each day faced the issue of improper payments.29 Schools weren’t being accurately compensated for discounted meals, creating errors in district and federal accounts. A 2015 USDA study found that the improper payment rate in the lunch program was 15.8 percent—$1.9 billion in overpayments and underpayments. In partnership with the Innovation Lab at the US Office of Personnel Management (OPM), FNS applied human-centered design (HCD) to discover the root cause of the errors. What was suspected to be a software glitch turned out to be a customer problem with most errors the result of an overly complex application process. The team used customer insights gleaned from observation and interviews with parents to design and prototype a simplified application. “As co-creators in the project, we saw HCD’s power to uncover root causes, rather than fix symptoms of public sector problems,” observed Jeff Greenfield, a manager of strategic initiatives and partnerships at USDA. FNS officials anticipate the simplified application will reduce improper payments by 10 percent, or $600 million, by the 2019–20 school year.30

Using CX to transform human services programs

Human services programs, too, can benefit from more tailored service strategies enabled by CX.

Although their core mission is to improve the trajectory of people’s lives, human services has long been more transactional rather than transformational. Instead of probing the circumstances that bring individuals and families into the safety net, and the problems that must be addressed to get them back on their feet, case managers tend to focus on simple classification—identifying the programs for which the individual or family is eligible.

The challenge is to understand what types of interventions are successful for different groups of people, so that individuals and families embark on the most appropriate path toward greater independence. Without a deeper understanding of what actually works for different groups, agencies may over-treat—or entirely miss—the problems that brought clients into the safety net.

That’s where CX comes in.

Segmenting customers by their “household DNA”

We all have a unique combination of characteristics that make us individuals: our employment history, financial circumstances, and educational background, among other things. Where we live, how we live, and with whom further shape us. Moreover, as individuals we exhibit specific behaviors in our reactions to different situations. In all, these characteristics and dispositions make up a distinct profile that can be called “household DNA.”

Yet, while each of us is unique, we also share commonalities with others at different points in our lives, in our financial or nonfinancial characteristics, in the way we interact with others. Some of these change over a lifetime while others remain constant.

By grouping clients according to their individual or household DNA commonalities, distinct clusters or segments emerge. These customer segments offer insights into their distinct attributes that can be used to determine individual needs based on the desired outcome and the most effective method and frequency of communication. More broadly, segmentation can help us better understand the needs of the population served, their preferences and behaviors and how those attributes may evolve over time.

Take the case of Jennifer, for example. In her eighteenth month of assistance, Jennifer reports that her employer has reduced her work hours by 10 hours a week, and that her husband has moved out. How has Jennifer’s “DNA” changed? How does she align with individual and household DNA segments based on her latest experiences? And what specific services and interactions have helped people in her position increase their work opportunities and overall financial health? By isolating specific events human services providers can identify and recommend services that have worked in the past for individuals with household DNA similar to Jennifer’s.

With this approach, individuals seeking assistance no longer confront a one-size-fits-all model that’s indifferent to their unique circumstances, but rather one that takes their household DNA profile into account and offers an evidence-based approach for getting them tailored assistance tied to meaningful outcomes.

Tapping into CX to boost employee engagement

Frontline employees play a pivotal role in shaping an agency’s CX. As the face of an agency for its customers, disengaged or unfriendly employees can negatively impact customer satisfaction. According to Tom Allin, VA’s chief veterans experience officer, “If you get high employee satisfaction, you’re going to get high customer satisfaction—it starts with the employee.”31 Yet VA employees often find themselves bound by rules and protocol that interfere with the customer experience. Can you give them permission to do what’s right for the veteran? Allin wants all VA employees to have what he calls “the courage of common sense,” to feel comfortable taking risks when it may help veterans. “You want them to understand what the minimums are but give them the freedom to engage themselves, and build that relationship,” he says.32

Making the connection between employee experience and its impact on the business can deliver powerful results. The sales organization at the United States Postal Service (USPS) made a similar effort to connect employee contributions and business impact through peer recognition of employees who created “moments that matter” for customers. The organization identified critical moments and associated behaviors, and then set up a simple online platform to recognize when others demonstrated these behaviors—and saw overall employee engagement rise by 8 percent in the initial pilot group.33

On the other hand, unhappy customers can lower employee morale, often resulting in attrition. It’s disheartening, particularly for frontline employees, to always be on the receiving end of negative customer feedback and issues. Empowering employees through training programs can help them be co-creators of CX, creating a virtuous cycle of employee and customer satisfaction.

By placing the customer at the heart of transformation initiatives—whether budget optimization, process improvement, or employee engagement—agencies can begin to achieve a broad range of mission outcomes.

Create a unified vision for change

It’s not hard to understand why the private sector is often so far ahead of government when it comes to CX. In addition to the obvious market forces requiring companies to compete on CX, private organizations have long had a chief marketing officer—and, increasingly often, a chief customer officer as well—whose job involves looking after the customer, whose recommendations carry weight, and who has a built-in budget to pay for CX improvements.

Contrast that capability with government agencies. Fewer than a quarter of federal managers surveyed in 2015 said their organization uses analytics to define customer segments, integrates its own data with those of other agencies, uses a customer relationship management system, or offers incentives concerning customer service. Furthermore, fewer than half of respondents believed that their organization does a good job soliciting feedback from customers, and only 42 percent said their organization uses quantitative metrics to track progress toward customer service goals.34

Creating a unified vision for change starts with an assessment of the organization’s current state and maturity with respect to customer experience.

The checkup: Assess your CX maturity

Experience is the way we feel about events and our interactions with people, organizations, facilities, and technology. It can be defined. It can be designed. And it can be improved.

But is improvement possible if you don’t know where you are at present? Probably not. That’s why professional athletes analyze their individual scores and performance statistics. It’s not just about winning or losing, but understanding how far they are from the goal, what is and isn’t working, so they can recalibrate their performance. The same is true for organizations.

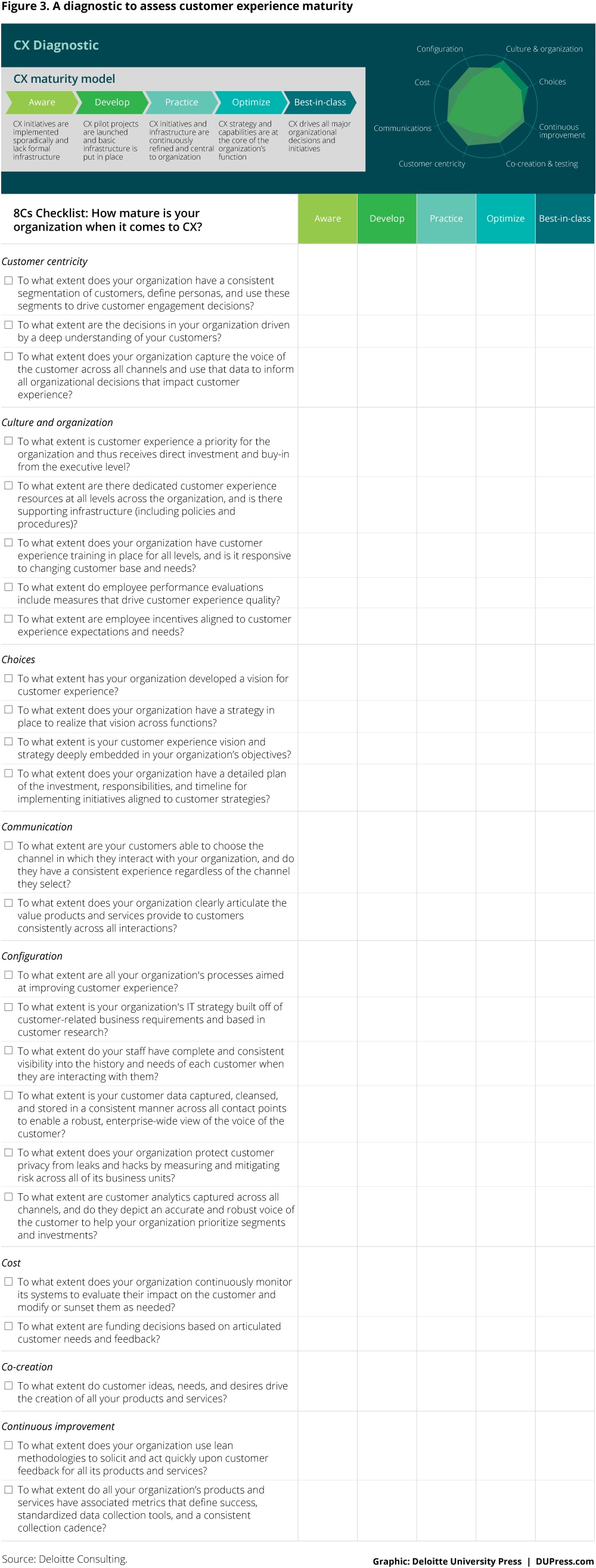

When it comes to putting CX to work in government to improve performance, many government agencies are still at the first stage of CX maturity wherein CX initiatives are implemented on an ad hoc basis in one part of the business and lack formal infrastructure (see figure 3).

The journey to becoming a more mature CX organization begins with an assessment of an organization’s commitment to CX, its current capabilities, and its vision for its customer and employee experience. The results of the assessment reveal an organization’s relative maturity along eight key dimensions and point to specific areas where organizations should focus their attention.

Define the CX future state

After defining the “as is” state, assessing CX maturity, and generating a clear picture of the organization’s core customer segments and their interactions with the system, the organization can define a more effective experience.

The future state vision or blueprint begins with basic design principles—core statements of what the system and culture will do. These principles become the basis for measurement and the test against which the program should be evaluated. A service design blueprint should address both front-end customer experience as well as the back-end operations, supporting decisions on business models, staffing, operations, training, and new services.

Returning to the case of VA, spending time understanding their customers and their journey illuminated unmet needs and pain points, as well as positive elements of their experience. The question then becomes, how can these bright spots be used to anchor broader improvements? For VA, the relationship veterans have with their doctors and health providers is generally viewed as a strength. Is there a way to take this positive element of the experience and amplify it through virtual care? Or take the case of military culture. After serving in the military, vets can relate to a certain way of living—structure and discipline, strong peer support, a sense of community and belonging, and a respect for teamwork. How can these familiar frames of reference be carried into their interactions with VA and ease the transition into civilian life? What if vets could navigate VA the same way they do the battlefield—in teams that supported one another, with a clear mission? Such considerations, when embedded into the future vision, can unlock creative ways to approach organizational problems.

For VA, progress meant reevaluating its role as a provider of health care. In mapping the end-to-end experience, it became clear that portions of the veteran experience lie outside VA’s control, making it part of a broader ecosystem including community health care providers, veteran-focused nonprofits, and other government agencies. Pivoting from its role as a provider of care to that of a facilitator and intermediary, VA is redesigning the Veterans Choice Program, which allows those enrolled in VA health care to receive health care within their communities. Veterans Choice allows those who live far away from VA facilities or need urgent attention to get care quickly.

Amtrak’s vision for its future state centers on customer needs. What if customers could have a seamless and consistent online experience with Amtrak across desktop, tablet, and mobile devices? What if they could use an app to request an Uber ride, reserve a table or seat, order and pay for meals, purchase amenities, and even receive alerts for sights to see along the journey? Amtrak found answers and added them to its redesign.

“We’re selling a journey, an experience, and not just a ticket on a train,” says Deborah Stone-Wulf, VP of sales distribution and customer service at Amtrak. “It has taken us a bit of time to understand that, but we do understand it, and that’s where we’re headed.”35

Whatever form the vision or blueprint takes, it provides direction on what changes need to take place across different parts of the business to realize the desired CX improvements.

Leadership and CX

Meaningful CX improvements in government require executive support, a mandate, and the resources needed to drive agency-wide improvements. As Forrester’s Rick Parrish observes, “No real customer-centered transformation can succeed without active sponsorship from the senior level…. you can get some stuff done, but without leadership, it’s just going be bits and pieces.”36

Since many government agencies operate in silos, it’s often difficult for agency leaders to make changes to CX because no single person or business unit owns all the touchpoints in the customer journey. As a result, making changes to one part of the business may inadvertently negatively impact CX in another.

As a result, it’s important for someone—be it a chief customer officer or a CX council comprised of leaders who collectively own all the touchpoints across the customer journey—to have a horizontal view across the entire agency and responsibility for ensuring that the customer experience is consistent across touchpoints that may span multiple business units. In recent years, a number of agencies have created a chief customer officer role including the General Services Administration (GSA), the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Export-Import Bank, and Federal Student Aid.37 Moreover, organizations are establishing CX councils that include representatives from every part of the organization that touches the customer—digital and technology specialists, program managers, human resources, and corporate communications, among others—to make coordinated changes across business units that are able to best meet the needs of their customers.

How did we do? Tracking metrics

When it comes to data, government agencies collect a lot of it—from user feedback, complaints, system logs, web analytics, and a bevy of other performance metrics, to third-party data such as the Best Places to Work in the Federal Government survey or American Customer Satisfaction Institute rankings, annual employee engagement surveys, and social sentiment scores that help identify the tone (positive, negative, or neutral) of social media chatter.

Often times what’s missing is not more quantitative data but rather the bigger-picture narrative that emerges when all of the data is stitched together and augmented with first-person ethnographic research. That provides a unified picture of what’s happening in terms of the customer journey across the enterprise and what the most important touchpoints are that have an outsized impact on CX and organizational performance.

Marrying quantitative metrics with qualitative customer feedback can help identify pain points as well as untapped opportunities within the organization. For example, when Canada’s postal service, Canada Post, analyzed data on customer loyalty in conjunction with package scanning metrics, it overturned a long-held idea that customers actually want to track every single step their packages take. The data showed that beyond a point, more scans didn’t increase loyalty and more information wasn’t necessarily better. With this knowledge, Canada Post was able to recalibrate its package scanning process and save money on expensive equipment it didn’t need.38

Making metrics actionable

To be useful in improving CX, data needs to drive what people who impact CX do day in and day out. In other words, data has to be served up in such a way that it’s operational. That means having a macro-enterprise view that cuts across all the silos and corresponds with the customer journey that enables executives to drive strategy and improvement initiatives. It also means making that data available so that it can drive what people on the frontlines actually do in real time.

Break down organizational silos through a macro, enterprise-wide view of CX

Today, customer interactions are no longer confined to a couple of channels. Keeping track of every interaction means expanding the boundaries of metrics tracking to include a host of social media channels and third-party review websites along with physical offices, service centers, call centers, and online channels.

Metrics are most valuable when they cut across organizational silos. Every employee in an organization—from executives to frontline staff and everyone in between—contributes to the experience customers have in some way or another. What’s needed is an enterprise view of customer data that aligns to the end-to-end experience and that enables employees at all levels to take actions that improve CX.

To understand how well the city is serving its citizens, the City of Boston created a unified baseball-inspired index. “CityScore” combines 24 different metrics from across city departments—from crime and Wi-Fi availability, to energy consumption, public safety, economic development, education, and health and human services, along with citizen satisfaction scores. A value above one means that things are going better than planned while anything less than one signals that intervention or remedial action is needed. Using the dashboard, city employees can monitor the delivery of city services, hone in on areas in need of attention, and make better decisions.39 According to Boston mayor Martin Walsh, “This actionable overview of city metrics will help us improve our city services and make our city safer and smarter.”40

Measuring feedback and performance on a regular basis also creates a cycle of continuous improvement and responsiveness to changing needs. The General Services Administration’s Office of Citizen Services and Innovative Technologies (OCSIT) has developed a Government Customer Experience Index (GCXi) to measure customer satisfaction across the 135 federal agencies it serves. Using index scores and qualitative feedback for different programs it offers, OSCIT can identify high-level areas for improvement across its programs. For example, in response to feedback indicating low awareness about some of OSCIT’s offerings, the office introduced more outreach programs and online “101” courses to introduce new users to its offerings.41

Support prioritized action, real-time and continuous improvements

Too often agencies find themselves with multiple areas in need of improvement, but limited resources to resolve every issue. Being able to see which areas have the greatest impact on customer experience and organizational performance can help agencies prioritize action. For example, when the LEGO group observed that declining delivery timeline scores were having a significant impact on satisfaction scores in Europe, it decided to prioritize improving that facet of its operations. Moving its warehouse to a more central location led to an immediate improvement in timeline scores and in turn customer satisfaction.42

The power of real-time data is that it can enable iterative feedback loops that drive continuous improvement. Find—Fix—Repeat. The private sector has figured out how to do this well by putting the right data in the hands of those who can act on it. For example, PayPal tracks customer experiences across service channels and transactions. Customer feedback is delivered in real time to the service center team. But feedback isn’t just delivered arbitrarily, it’s assigned to those members who are best qualified to take action on a particular item—it’s customized. The result: Each of PayPal’s service centers and nearly 9,000 agents have the precise information they need to meet customer needs and make pointed improvements.43

Overall, metrics, data gathering, and data integration tools can complement but not substitute for the core process of knowing your customer through interviews, observation, journey mapping, and other techniques. These exercises allow organizations to understand where listening posts and metrics need to be set up and to make sense of the intelligence that analytics can provide.

Conclusion

Recent years have seen a renewed government focus on improving customer service. While many government agencies have invested significant amounts of time and money trying to improve customer service, these efforts haven’t yet translated into meaningful improvements in customer satisfaction with government services, which remains at an eight-year low.

Improving CX, however, requires embarking on a journey of discovery. It means leaving behind preconceived notions about why things are the way they are, and seeing things anew from the customer’s perspective.

Two misperceptions in particular often thwart the best-intentioned improvement initiatives.

First, agencies often approach CX issues through the lens of assessment: “How are we doing?” “What accounts for the half-point drop in customer satisfaction last quarter?” When scores go down or a customer problem is flagged, the natural disposition is to explain why: “The customer filled out the form incorrectly.”

Improving CX, however, requires embarking on a journey of discovery. It means leaving behind preconceived notions about why things are the way they are, and seeing things anew from the customer’s perspective. Adopting a CX mind-set often entails arriving at a different explanation as to why: “The form is confusing for new customers.” This focus on discovery opens up new possibilities for improving the customer experience and, in turn, organizational performance.

Second, improving customer experience is not a one-time event, but rather represents a new way of operating, with the requisite executive focus and enabling infrastructure that have led to the kind of sustained improvements in CX we’ve seen leading private sector enterprises make over the last decade.

Moving the needle on customer satisfaction with government services requires embracing the CX mind-set as a powerful lever for performance improvement, which places the customer at the heart of transformation initiatives. Realizing the mission benefits derived from delivering a better customer experience will not happen overnight. Public sector organizations must cultivate the culture, skill sets, and infrastructure necessary to support a customer-focused organization. So much the better for government agencies that start down this path sooner than later.