Making it Millennial has been saved

Making it Millennial Public policy and the next generation

03 April 2014

The well-being of any society depends on each successive generation’s ability to contribute to the common good. Yet today’s rising generation, the Millennials, faces many obstacles to success.

Introduction

Millennials, the rising generation of adults in the United States born between 1980 and 1995,1 are a topic of societal fascination. A quick Internet search returns more than 15,000 blog posts, editorials, and news articles on Millennials, in which they are characterized by adjectives as varied as apathetic, engaged, selfish, civic, entitled, and impatient. They are the focus of popular television shows and box-office hits. In boardrooms, marketers suggest how to appeal to them as consumers, while managers contemplate how to attract and retain them as employees. At dinner tables across the country, parents and grandparents fret about their plans for the future.

The story is not new; the young have always concerned their elders. Circa 500 BC, Socrates swore the youth of his day loved luxury, displayed poor manners, and contradicted their parents and teachers.2 A letter to the editor of the Atlantic, published in 1911, describes the rising generation as shallow, amusement-seeking, and selfish.3 In 1990, Time magazine ran a cover piece on Generation X, which labeled it indecisive and unmotivated.4 The concern is reasonable, if somewhat clichéd by now. As with every rising generation, the stakes for success are incredibly high. The future quite literally depends on it.

Today’s rising generation, the Millennials, faces a particularly bumpy path down the road to success. Millennials’ coming of age corresponds with a global financial meltdown, a housing bust, the worst recession in the United States since the Great Depression, and soaring higher education costs. While Americans of all ages share these same experiences, the ways in which they impact the rising generation, both now and in the long term, are unique. Consider the economic environment in which today’s young people currently operate, and the changing family planning and consumption trends among the Millennial generation.

Economic realities

Millennials entered the workforce during or in the wake of the Great Recession. Among Millennial college graduates, unemployment and underemployment, at 8.8 percent and 18.3 percent respectively, are historically high compared with the same age cohort in prior generations, and wages for employed Millennials have dropped 7.6 percent since the onset of the Great Recession.5 High unemployment levels and low wages are making it difficult for many Millennials to make even minimal payments on their record-high amounts of student loan debt. At present, loan default rates are approaching historic highs, damaging Millennial credit scores along the way.6

Social realities

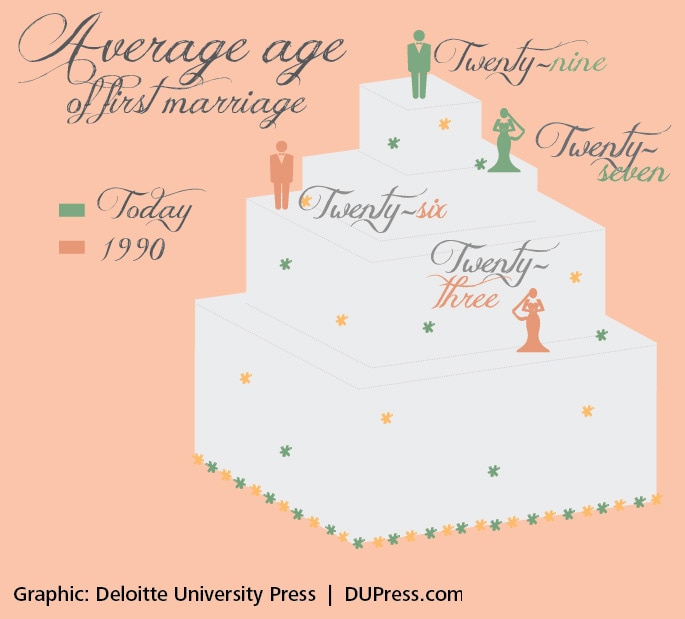

Millennial marriage and family formation trends also differ from those of past generations. The average age of first marriage in the United States is now 27 for women and 29 for men, up from 23 for women and 26 for men in 1990.7 The total fertility rate—or the average number of children each woman is having—is at 1.93 among Millennials,8 compared with 2.1 for Generation X.9

While some of the delay in marriage and child rearing can be explained by economic circumstance, these trends predate the Great Recession. Instead, they are closely related to a series of cultural changes over time that include more women in the workforce, the increased prevalence of higher education among women, and greater social acceptance of premarital sex, birth control, and cohabitation before marriage.10

Consumer realities

Given economic realities and delays in family formation, it’s not surprising to see reduced Millennial consumption of big-ticket items. Many Millennials are simply unable to purchase cars or homes due to poor job prospects, student loan debt, and lack of access to credit. According to decennial US census data, homeownership among 25- to 34-year-olds was at 42 percent in 2010, compared with 52 percent among 25- to 34-year-olds in 1980.11 There is also a decline in Millennial new car purchases. According to a report by CNW Research, Millennials account for 27 percent of new vehicles sold in the United States, compared with 38 percent of new vehicles bought by Generation X at the same point in life.12

Implications for government

Whether Millennials are adequately equipped or positioned for the future is still largely unknown—the generation is only in the very early stages of writing its own chapter of history. But like every generation before the Millennials, there is a lot riding on their success: the level of tax revenues, the level of demand for public assistance, the speed of economic growth, and the ability to honor the intergenerational contract that supports the social safety net.

Perhaps a less tangible concern, though arguably as important, is the future of the “American dream” itself. Americans have always believed that with hard work, they will find opportunities for success, prosperity, and upward mobility. But 2013 polling data show that only 15 percent of the country believes that today’s children will be better off than their parents were.13

The way Millennials live—their opportunities and constraints; the choices they make while navigating their formative years—will shape American society and ultimately impact governments at the federal, state, and local levels. Through analysis of current economic, social, and consumption trends, this paper considers the potential future for the Millennial generation, associated impacts on government, and potential mitigating strategies. The paper is not meant to predict whether current trends will endure; it instead considers the potential implications of current trends on the future, described through trend analysis. The research is based on a comprehensive literature review, a quantitative trend analysis, and extensive interviews with experts in generational dynamics, sociology, demography, economics, and governmental structure.

While the economic, family planning, and consumption trends examined in this paper certainly manifest differently for different segments of the Millennial generation, the frame of reference for the paper is generally that of young Americans with some college education,14 who account for more than 50 percent of the generation as a whole.15 In modern history, young people have pursued higher education to increase their likelihood of success with positive outcomes, and education is generally referred to as a societal equalizer.16 A focus on Millennials equipped with the standard tool for success provides unique insight on the potential significance of the trends discussed throughout.

Economic realities: The Millennial economy

For Millennials, the employment picture is challenging. The unemployment rate among Millennial college graduates is 8.8 percent.17 The underemployment rate among Millennial college graduates—a measure of part-time workers looking for full-time work, and workers not making full use of their skills in their full-time positions—is 18.3 percent.18 Additionally, average wages among employed Millennials are down nearly 8 percent since the Great Recession began.19

Graduating during a recession or depression could result in substantially less income over the lifetime of the Millennial earner. A recent Yale study found that starting from a lower base income has significant effects in each subsequent year of an earner’s lifetime. The trend persists over the long term, as recession-era graduates in this study “earned 4 to 5 percent less in their 12th year out of school and 2 percent less by their 18th year.” For a typical worker, this loss amounts to roughly $80,000, in real terms, over a 20-year period.20

Graduating during a recession or depression could result in substantially less income over the lifetime of the Millennial earner. A recent Yale study found that starting from a lower base income has significant effects in each subsequent year of an earner’s lifetime. The trend persists over the long term, as recession-era graduates in this study “earned 4 to 5 percent less in their 12th year out of school and 2 percent less by their 18th year.” For a typical worker, this loss amounts to roughly $80,000, in real terms, over a 20-year period.20

Graduating during a recession

Millennials are not the first generation to graduate into a recession. Late Baby Boomers faced a tough economic outlook in the early 1980s, and Gen X graduates confronted economic downturns in the early ’90s and again in the early 2000s. But the Millennial situation is unique. The Great Recession was the longest recession since the Great Depression, with a sustained higher unemployment rate than the recessions of the 1980s, 1990s, or early 2000s. Additionally, there continues to be only modest job growth in the current recovery, compared with robust job growth in the recovery of the 1980s. Though the recessions of the ’90s and early 2000s were also followed by modest job growth, the base rate of unemployment was five and seven percentage points lower, respectively, during these recessions.21

The economic outlook

The economic outlook for unemployed and underemployed young people is uncertain. Dr. Harry Holzer, Georgetown public policy professor and former chief economist for the US Department of Labor, notes that although the economy will almost certainly get better, there remains reason for concern. In the long term, the economy may look similar to the period of 2000–07, when job growth stagnated even though the market was strong. Holzer noted with some optimism that “no one saw the boom of the ’90s coming,” with a caveat that he did not know anyone who thought we would get back to the growth of the ’90s.22

Learn more

In our Millennials collectionProlonged unemployment and underemployment among the Millennial generation could also impact future generations. Long-term unemployment has negative impacts on family well-being, and for children with unemployed parents, it is associated with poor academic performance, risky behavior, and impaired social relationships.23 Additionally, lack of either real or perceived economic opportunity for one generation dampens optimism among the next generation, according to Jason Peuquet, research director at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, who added, “From a human capital perspective, this is just another reason why we could grow even slower. And to be quite frank, we don’t need any other reasons.”24

Millennial entrepreneurship

A recent report by the Kauffman Foundation and the Young Invincibles indicates the entrepreneurial spirit among the Millennial cohort is strong. More than 50 percent of survey respondents said they would like to start their own business; 38 percent of those respondents, however, said they’d delayed starting a business due to the economy.25 The predominant concern was access to capital, as 41 percent of respondents stated they were not eligible for a line of credit needed to start a business. The results in this survey are echoed in a recent report by the Small Business Administration, which found a 19 percent decline in entrepreneurship among Millennials age 25 and under from 2005 to 2010. 26

More than 50 percent of survey respondents said they would like to start their own business; 38 percent of those respondents, however, said they’d delayed starting a business due to the economy. . . . 41 percent of respondents stated they were not eligible for a line of credit needed to start a business.

Policy impact: Decreased tax revenue

The economy is creating fewer jobs, and this might be the case for the foreseeable future.27 Many of the jobs that do exist require specialized skills and are highly competitive. As such, Millennials could continue to struggle to find and maintain gainful employment, which will impact contributions to federal, state, and local tax revenues in the short and long term.

Entitlement programs

The Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) estimates for Social Security and Medicare are already bleak. In the 2012 Long-Term Budget Outlook, the CBO reports, “If current laws stay in place . . . the aging population and the rising cost of health care would cause spending on major health care programs and Social Security to grow from more than 10 percent of GDP today, to almost 16 percent of GDP in 25 years.” It goes on to say that, absent substantial increases in federal revenues—which primarily comprise income and payroll taxes—such growth in outlays would result in greater burdens than the United States has ever experienced.28

CBO projections could be optimistic, given what is known about the current economy and expert opinions on prospects for long-term economic growth. In a worst-case scenario, insolvency could come much sooner for Medicare and Social Security, which would be problematic for the Millennials’ Boomer parents, 51 percent of whom are at risk of not having saved enough to maintain their standard of living after retirement.29

The economic situation of the Millennial generation only exacerbates concerns regarding Boomer retirement security. As Millennials struggle to find employment and pay their student loans, they are relying on support from their parents to make ends meet. A 2012 Pew report found that 48 percent of Baby Boomers still support their children financially, and 27 percent serve as the primary supporter of their grown kids.30

Money spent by Boomer-generation parents to finance the food, shelter, communication, and transportation needs of their children comes with an opportunity cost—it is money that could otherwise bolster their retirement funds. But if Boomer parents were not supporting their Millennial children, there would likely be increased demand for public assistance by young people unable to support themselves in the current economy. The societal trade-off, then, is between paying for the increased need for public assistance now and deferring it to later into Baby Boomers’ retirement years.

States and localities

Poor job prospects and low wage growth among the Millennial generation could also adversely impact state government tax receipts. This is particularly concerning because state and local revenues are already in decline across the country, due to weak tax collections following the Great Recession.31 States that rely heavily on revenues from individual income taxes and states that rely heavily on sales and gross receipt taxes—assuming that lower wages and higher unemployment impact Millennial consumption—stand to lose the most.

Across the 50 states, individual income taxes account for 20 percent of all revenues. Reliance on income tax receipts varies from state to state, with some states, such as Florida and Texas, collecting no income tax at all. In states such as Oregon and Maryland, though, where roughly 35 percent of revenues come from income taxes, the burden could be significant.32 Sales and gross receipt taxes account for 34 percent of revenues across all states; however, in states such as Washington, Tennessee, and Louisiana, these taxes account for more than 50 percent of all revenues. In these states, downward shifts in consumption among the generation could greatly strain budgets.

Mitigating strategy #1: Increase youth employment programs

Millennials need opportunities for gainful employment—and the sooner the better. At the federal level, the government could increase investments in job- and service-oriented youth programs. For example, AmeriCorps funds community service positions at not-for-profits, schools, public agencies, and community- and faith-based organizations across the country. AmeriCorps volunteers receive benefits that include cost-of-living allowances, student loan deferment, and education awards that can be used to pay for college costs or student loan debt.33

Expanding AmeriCorps, and other federally funded programs with similar benefits, could get young Americans to work quickly. Though the program provides only modest wages, it gives young people a valuable opportunity to gain work experience in a degree-related field while remaining active in the workforce. Additional benefits include reduction in student loan debt—a significant burden for Millennials, covered in the next section of this paper—as well as access to resources that help alumni translate their AmeriCorps experiences into full-time jobs.

Mitigating strategy #2: Develop or expand local community partnerships

In the short term, an increase in partnerships between industry, academia, and state and local governments can improve on-the-ground conditions without federal intervention in many communities across the country. In some areas of the country, similar partnerships are already successfully in place. A partnership between the United Parcel Service (UPS), the Jefferson Community and Technical College (JCTC), and the state of Kentucky is one such example. UPS, a major employer in Louisville, considered leaving the city due to talent shortages in the late 1990s. Through negotiations, it instead worked with state and local officials and JCTC to create Metropolitan College, a higher education and training program for UPS. Half the cost of the program is covered by UPS, and the other half is covered by the public sector. Students attend courses while working part-time at UPS with full benefits. Since its inception, 2,200 people have received a degree from Metropolitan College, and UPS has seen an 80 percent increase in worker retention.34

Mitigating strategy #3: Support Millennial entrepreneurship

The Millennial generation, though decidedly entrepreneurial, will not be able to start businesses without access to capital. At the local level, community banks can provide microcredit for Millennial businesses, with academic institutions, incubators, and lenders determining eligibility and selection criteria. Financial institutions and social enterprises in developing nations around the world employ similar microfinance techniques in an effort to combat high levels of youth unemployment. The Alexandria Business Association in Egypt provides one successful example. The association finances modest group-based loans without collateral requirements, and it links the borrowers to entrepreneurship training and financial education courses as a part of the loan agreement.35

At the federal level, the US government could mitigate the issue of access to capital by backing a subset of small business loans specifically geared toward young people. At present, small business loans generally require a decent credit score, sufficient equity investment by the borrowers in their business, and collateral assets. These are difficult standards to achieve for young people, especially those with high debt levels. A version of the Small Business Administration’s loan program, geared toward Millennials, could provide small loan amounts over shorter periods of time, mitigating the risks associated with default. The loans could be renewable at larger amounts contingent on successful repayment and completion of financial literacy courses. A program similar to this would help Millennials build positive credit over a period of time, at which point they could transition to a traditional small business loan.

Economic realities: High levels of student loan debt

For the Millennial generation, costs associated with pursuing a college degree are higher than ever. College tuition continues to rise each year at two to four times the rate of inflation, making it four times more expensive to attend school than it was 20 years ago.36 Tuition is also rising at a much faster rate than family income. The percent of median household income needed to pay for tuition is now 35 percent, compared with 19.5 percent 20 years ago.37

More Millennials are borrowing to pay for their education than generations past, and the average cumulative debt among Millennial undergraduates is also on the rise.38 In the graduating class of 2012, 71 percent of students took loans averaging $29,400. Compare this to 1992, when 49 percent of students took an average of $15,000 in student loans, in real dollars.39 The long-term impact of student loan debt will be significant. According to a recent study by the think tank Demos, a college-educated couple with the average amount of student loan debt will see a reduction of more than $200,000 in lifetime wealth accumulation.40

The percent of median household income needed to pay for tuition is now 35 percent, compared with 19.5 percent 20 years ago.

Student debt is increasing, while the ability to pay debt is decreasing. College graduates are now, more than ever, struggling to realize the return on the investment in their education. A recent report on the status of graduating classes during 2009–12 indicates that 48 percent are currently working at jobs that require less than a four-year degree.41 In part, this is related to the economic downturn. As previously noted, Millennials across the board are struggling with high levels of unemployment and underemployment coupled with low levels of wage growth.

Not all college graduates face the same struggles on the job market. Graduates with degrees in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields are faring better than their counterparts with liberal arts degrees.42 This highlights the American “skills gap”—or the mismatch between the skills possessed by job seekers and those required by employers. A recent report noted that, while more than 70 percent of colleges and universities think graduates possess the right skills to enter the labor market, only 42 percent of employers agree.43

The price of college continues to rise each year, even as the economic value of many degrees has been stagnant for a decade.44 Clayton Christensen, the preeminent scholar on disruptive innovation in higher education, says this is a result of American universities placing a higher premium on prestige than on the return on investment a student gains from the education.45

Christensen explains that for decades, traditional universities—similar to businesses in many other industries—focused primarily on getting “bigger and better,” under the assumption that becoming more prestigious and reputational would be the best way to serve all their constituents.46 As such, universities across the country made significant investments in “growing the number of courses and degrees offered, adding graduate programs, doing more research, and trading up to bigger athletic conferences,” all while increasing admissions selectivity.47

Higher education’s “bigger and better” strategy did successfully create bigger and arguably better universities, able to provide higher education to larger swaths of the population and, by extension, improve social and economic welfare in the United States overall. But in the wake of the Great Recession, many universities are faced with shrinking endowments, cuts in government subsidies, and increased scrutiny on the value of higher education. The unsustainable costs associated with pursuing a “bigger and better” growth strategy are now obvious and pressing.48

Higher education’s “bigger and better” strategy did successfully create bigger and arguably better universities, able to provide higher education to larger swaths of the population and, by extension, improve social and economic welfare in the United States overall. But in the wake of the Great Recession, many universities are faced with shrinking endowments, cuts in government subsidies, and increased scrutiny on the value of higher education. The unsustainable costs associated with pursuing a “bigger and better” growth strategy are now obvious and pressing.48

Another explanation for rising tuition costs is the accessibility of federal financial aid. In 1987, then-Education Secretary William Bennett wrote in a New York Times opinion piece, “Increases in financial aid have enabled colleges and universities blithely to raise their tuitions, confident that Federal loan subsidies would help cushion the increase.”49The argument, since titled the “Bennett Hypothesis,” states that instead of improving college affordability, increases in student financial aid insulate universities from pursuing market-driven efficiencies such as cutting costs and improving productivity.50

Policy impact: High levels of debt and limited access to credit

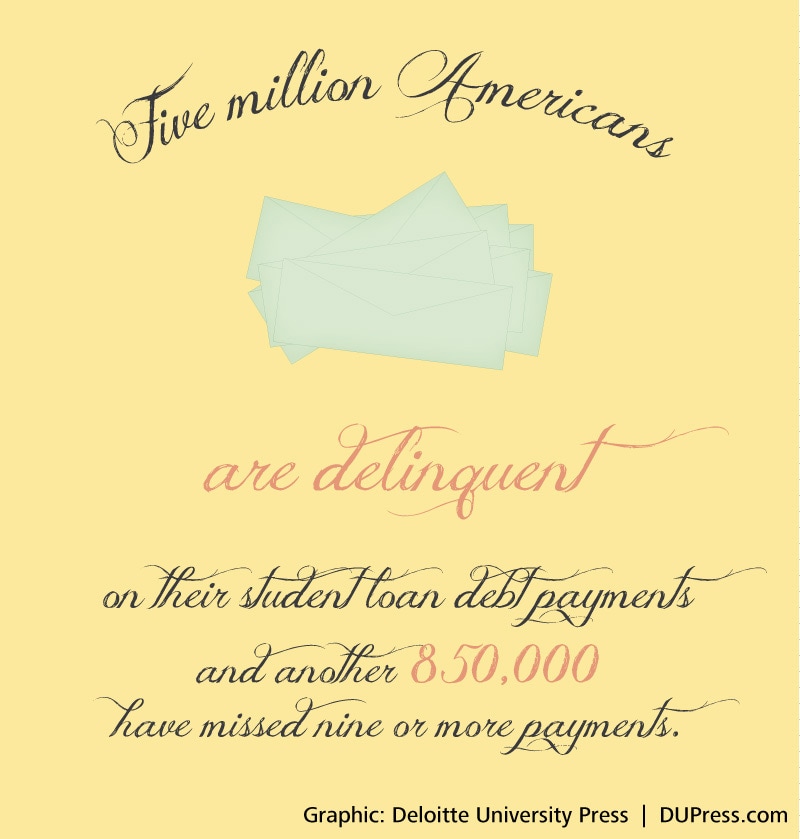

Assuming regular payments, student loans can take up to 25 years to pay off entirely; however, unemployment and low wages have made it difficult for many Millennials to make minimal loan payments early in their careers.51 As a result, student loan delinquency and default rates are approaching historic highs and damaging Millennial credit scores along the way.52

Delinquency, which begins one day after a missed payment, is now higher among student loan borrowers than holders of any other kind of debt.53 An estimated 5 million Americans are currently delinquent on their student loan debt payments.54 An additional 850,000 Americans have defaulted on their student loan debt, meaning that they have missed nine or more consecutive payments.55

Default on federal student loans can have serious consequences for the borrower and, unlike privately held debt, cannot be shed through bankruptcy.56 The federal government can garnish wages without a court order and deduct money from Social Security benefits, disability checks, and tax refunds. In addition, the government can charge late fees and penalties or sue the borrower.57 The long-term impacts of defaulting on federal debt include damage to credit scores and jeopardizing access to future credit.

Policy impact: Declining reputation of the American higher education system

The US university system is already at risk of losing its “best in the world” reputation, as citizens, employers, and credit agencies alike question its value and sustainability. Recent Pew polling data indicate that 57 percent of Americans believe the US higher education system fails to provide students with good value for money.58 Only one out of every four employers believes that the higher education system is preparing students for a globally competitive economy.59 Recently, the credit agency Moody’s downgraded the whole US higher education sector’s outlook to negative based on strained resources, the negative perceptions of the industry due to student loans, and the prospects for long-term sustainability.60

Advances in other countries are only exacerbating the problem. Traditionally, the United States has been able to attract top talent from around the world, especially in STEM fields, but countries such as China and India are not only improving their own educational systems, but also providing better employment opportunities for their homegrown graduates. As other countries improve their education and employment opportunities, the US system risks a decline in enrollment from international students and a decline in public perception of the American university system overall.61

For now, the United States is still home to the majority of the world’s top-ranked universities.62 Each year the system attracts millions of students from across the country and the world.63 In 2012, more than 17 million Americans and nearly a million international students were enrolled in the US university system—paying tuition and subsidizing ongoing operations.64 But if the disconnect between the cost and value of attending America’s traditional universities continues, and global university systems improve at the same time, the United States’ reputation as a world leader in higher education could suffer.

Mitigating strategy #1: Simplify student loans and repayment

In the near term, the federal government could consider a series of policy shifts to stabilize debt burdens among the Millennial generation of students, which in turn would reduce delinquency and default rates. A good starting point might be simplifying the student loan system, which currently includes a complicated mixture of grants, loans, work programs, and repayment options that students struggle to navigate. In a recent survey by the Young Invincibles—a national organization that represents the interests of 18–34-year-olds—65 percent of respondents said they did not understand aspects of their student loans or the student loan process.65 Additionally, despite federal mandates, 40 percent of respondents said they did not receive loan counseling from their school.66

To streamline the student loan system, the government might consider offering a single type of grant and loan system for college students, with income-based repayment (IBR)67 as the default repayment option—a measure that more than 75 percent of students support.68 A single type of financial aid, with consistent and predictable application standards, interest rates, and repayment options, might mitigate the difficulties students face understanding the loan process. In addition, IBR as a default option for loan repayment immediately following graduation could help students manage their debt levels during a volatile life stage. Though IBR is already an option for struggling graduates, of the 5 million Americans currently in default on their debt, only 1.1 million borrowers are enrolled in IBR plans.69

There are trade-offs to implementing automatic enrollment in IBR. Primarily, it would necessitate a shift of federal resources away from subsidizing interest rates—currently a policy lever in providing affordable education to low- and middle-class borrowers—in favor of supporting sustainable loan repayment after graduation.70 Research by the Young Invincibles indicates low interest rates do little to improve access to education or completion rates, though.71 The group suggests that IBR as a default, coupled with a single, predictable interest rate, could make the IBR program budget-neutral over the long run, while more efficiently allocating federal financial assistance through sustainable repayment options to those in greatest need.72

In addition, some changes to current IBR programs should be enacted to ensure efficiency. For example, as currently structured, IBR programs stand to provide the largest benefit to borrowers with high federal debt and high incomes. Often these are borrowers with graduate or professional degrees, who may not have the greatest need for repayment assistance.73 Repayment requirements should be modified to correct this and similar loopholes prior to implementation.

Mitigating strategy #2: Standardize accreditation for online learning

A second set of policies could address the rising costs of higher education by encouraging growth in online education. Institutions that develop or leverage new technology and online learning platforms can reduce overhead costs associated with higher education while expanding access to more students across the country and around the world.74 However, barriers to growth exist in this industry, a prominent one being accreditation.75

Accreditation is meant to ensure consistent standards of quality across the higher education market. In higher education, it is a de facto prerequisite for successful institutions, given that students must attend accredited learning programs to qualify for federal financial aid, and that they are generally only able to receive transferrable credit for courses taken through accredited institutions.76

Antiquated standards for accreditation create significant barriers for online education institutions that leverage new learning models. The process is rigid and onerous and relies on evaluation standards, such as site visits, that favor traditional and established models for higher education.77

The US government could update accreditation standards so they more accurately assess the quality of education received across online and residential education programs, and lessen barriers to entry for new competition in the higher education market. An overhaul in current accreditation practices could unleash a whole new educational experience online, at a much lower price point, and force market efficiencies in traditional higher education. Students could leverage the massive open online course (MOOC) revolution to achieve a full degree, selecting requisite courses from companies such as StraighterLine, Udemy, Coursera, and EdX based on costs and peer reviews.78

Social realities: Delayed marriage and declining birth rates

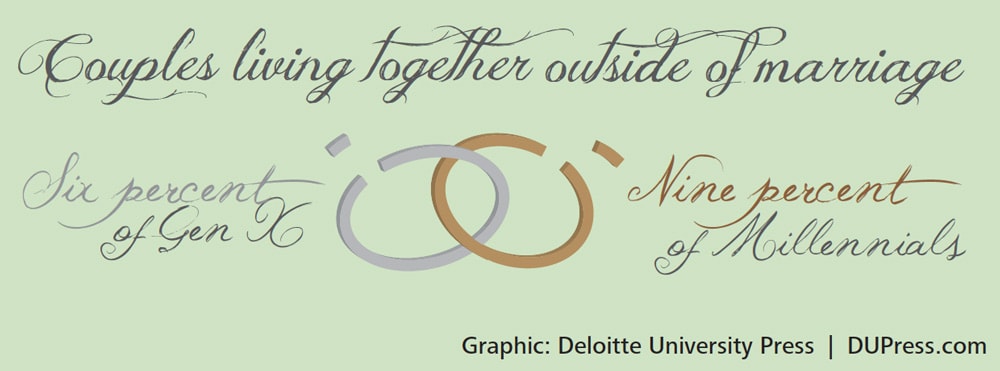

Millennials show different social and cultural trends around marriage and family formation than previous generations. Millennials are marrying later and cohabting with a partner before marriage at rates higher than ever before. The average age of first marriage in the United States is now 27 for women and 29 for men, up from 23 for women and 26 for men in 1990.79 Additionally, 9 percent of Millennial couples are currently living together outside of marriage, up from 6 percent among Generation X at the same point in life.80

Dipping below the replacement rate

Millennials are having fewer children than previous generations did. According to a recent Pew report, since 2008 the number of births in the United States has dropped to the lowest level in history.81 The US total fertility rate is currently 1.93, below the replacement rate—the rate of births needed to maintain a stable population—of 2.1.82A major driver of this trend is the decline in births among minority women. While the recession may partially explain this trend, increased educational attainment among minority women is likely another contributing factor.83

One out of every 12 first births in the US is now to a woman age 35 or over, compared with 1 out of every 100 first births in 1970.

Delay might mean decline

Women who do have children have them later in life. The average age for a woman’s first birth is now 25 in the United States, up from 21.4 in 1970.84 Additionally, 1 out of every 12 first births in the United States is now to a woman age 35 or over, compared with 1 out of every 100 first births in 1970.85

American attitudes toward having kids remain stable, with most people still believing it ideal to have at least two children.86 So the story around fertility in the United States may be more about delay than decline in the long run, which could be positive, as the delay that drives lower birth rates may produce better outcomes for the well-being of Millennial children. Dr. Anastasia Snyder, a family science professor at Ohio State University, explains that parents who delay childbirth are typically in better economic positions, with more stable relationships and calmer parenting styles. These characteristics generally lead to a stable early life and are associated with positive outcomes for children.87

However, delays in childbearing have a biological impact on women, which may ultimately result in a decline in childbearing, irrespective of a family’s preference for two children. Female fertility gradually declines after the age of 28, and by the age of 35, a woman’s chance of conceiving naturally is cut in half.88In addition, the health risks to mother and child increase in pregnancies among women over 35, making it more difficult to carry a child to term.89

However, delays in childbearing have a biological impact on women, which may ultimately result in a decline in childbearing, irrespective of a family’s preference for two children. Female fertility gradually declines after the age of 28, and by the age of 35, a woman’s chance of conceiving naturally is cut in half.88In addition, the health risks to mother and child increase in pregnancies among women over 35, making it more difficult to carry a child to term.89

Emerging adulthood

Why are Millennials taking so long to get married and have children, or deciding not to do it at all, and will the trend reverse with the economy? Snyder subscribes to the view that today’s young people see their 20s as a time of self-exploration, rather than a time for settling down. This is commonly called “emerging adulthood theory,” a term coined by psychology professor Dr. Jeffery Arnett, the preeminent scholar on the topic.90

Emerging adulthood theory states that young adults are no longer following the traditional path to adulthood, marked by five milestones: completing school, leaving home, becoming financially independent, getting married, and having a child.91In the 1960s, 77 percent of women and 65 percent of men achieved all of these milestones by the time they turned 30. In the 2000s, less than 50 percent of woman and 33 percent of men had accomplished the same.92

A series of societal value and attitude shifts underlie emerging adulthood theory. Specifically, emerging adulthood can be explained by a mix of social and cultural developments over the past 20 years, including the increased demand for higher education, particularly among women; the general increase in acceptance of premarital sex, birth control, and cohabitation before marriage; an increase of women in the workforce and better career trajectories for working women; and the extended timetable for women’s reproduction.93

When asked whether these trends could more simply be explained by the down economy, Snyder said that while the current labor market is an important factor in some of the delayed behavior, these trends predate the Great Recession.94 She expects this to be long-term: “I don’t think this is some sort of temporary response to an economic or historical shock in some way.”95 This view is reinforced by a movement of psychologists, sociologists, and neuroscientists, who, in light of new research on cognitive development, are working to officially change the definition of adolescence to extend from 18 into the mid-20s.96

Advances in neuroscience make it clear that brain development, specifically in the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for reasoning, planning, and problem solving, continues in young people into their mid-20s. While the brain has presumably always worked this way, for the first time economic and cultural changes have aligned to make the delayed transition to adulthood a more socially acceptable path for young people. In the words of New York Times Magazine contributing writer Robin Marantz Henig, “The rate of societal maturation can finally fall into sync with the rate of brain maturation.”97

Policy impact: Greater strain on the social safety net

The decline in fertility rates, if not countered through increased immigration, could pose significant challenges to the United States.98 As future generations retire, declining birth rates will exacerbate mounting pressures on the social safety net by upsetting the worker-to-retiree balance. In 1970, there were five working Americans for every retired American. By 2025, that ratio will decline to 3:1.99 The impact on the next generation will be substantial, as the estimated economic burden on a child born in 2015 will be nearly twice that of a child born in 1985.100

Policy impact: Lower growth and productivity

Declining population growth could be associated with lower economic growth rates and a decline in innovation.101 Take the case of Japan, a country where more adult diapers were purchased in 2012 than baby diapers.102 Since the 1990s, the country has experienced lower GDP growth, deflation, and higher levels of public debt. Though Japan’s economic problems are also related to macroeconomic mismanagement, the trends are exacerbated by the country’s aging crisis.103

According to a recent working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, older people have greater economic needs and provide fewer economic contributions.104 As a result, economies with a higher proportion of older people tend to have lower labor supply, productivity, and savings—key contributors to economic growth. In effect, “other things equal, a country with a high proportion of elderly people is likely to experience slower growth than one with a high proportion of working-age people.”105 At the same time, as people stay in the workforce for longer periods of time, it is reasonable to assume this dynamic will change to some degree. Cultural norms will shift, and technological improvements will increase productivity over longer periods of life, which could ultimately mitigate some of the impact of an aging population.

Mitigating strategy #1: Pursue population growth policies

Increase total population growth

The United States educates many foreign-born workers in STEM fields, which are increasingly important to the US economy. Many of those students are in the United States only on temporary visas, and absent a job and company that will sponsor them after graduation, they return back home, taking their talent with them. Current proposals for immigration reform seek to expand visa opportunities for foreign-born STEM-educated students. If passed, this reform could both increase the US population and fill a gap in the country’s labor pool.106

Increasing total population growth through immigration reform could also help to fix the current imbalances in the worker-to-retiree ratio in the United States. The “proportion of the United States population between the ages of 25 and 44 is 25 percent higher when including foreign-born workers than when considering native-born alone.”107 Immigrants also have higher birth rates than native-born Americans, and increasing the number of foreign-born workers in the United States could in turn increase the country’s overall birth rate.

Increase natural population growth

Examples of government policies that seek to increase the number of child births in a country include child-bearing tax incentives, generous parental leave policies, and child-care assistance policies, to name a few. Compared with most Western countries, these kinds of family policies are limited in the United States, though the income tax deduction for dependents provides one example.108

France and Sweden have much more expansive pro-natal policies, as each country devotes approximately 4 percent of GDP to support families.109 Programs provide up to one year of paid parental leave (with costs split between the government and employers), state-sponsored child care, and the ability for a parent to return to work either full- or part-time after having a child without penalty. Given the declining childbirth rates across Europe, both countries have fared comparatively well, staying just below the replacement rate.110 In Germany, pro-natal policies have been less successful at increasing the child birth rate, but studies indicate they have led to an increase in parent happiness and child well-being.111 In countries with declining birth rates, these outcomes are arguably just as important. With fewer children, there is greater weight on the success of each individual child.

The United States could consider some combination of expanding tax credits for families and expanding benefits to parents to encourage higher child birth rates domestically. In the event the policies do not actually make strides in increasing the US population, they may result in better child outcomes overall, which could still be considered a success.

Mitigating strategy #2: Plan for less

The United States could instead accept the declining working-age population and plan to mitigate the consequences for the social safety net. The government could employ strategies such as increasing the eligibility age for Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries or means-testing benefits to limit them to those who need them.112 From a growth perspective, GDP is a measure of the total number of workers in an economy and the productivity of each of those workers. Population decline will decrease the total number of workers in the US economy, and if productivity remains constant, GDP will in turn decline.113 Changing cultural norms and technological breakthroughs could also increase the longevity of each worker, in effect naturally mitigating some of these adverse impacts.

Assuming there is a decline in the US working-age population, and with it an increase in the sizable strain on the social safety net, the public and private sectors will need to work together to devise measures that increase the productivity of a smaller workforce.114This should begin with steps to bring the workforce closer to full employment, including public and private investments in job creation. Additionally, public and private focus on increasing innovation and technological advancements can facilitate worker productivity and mitigate the impacts of a shrinking workforce.115

Consumer realities: Declining car ownership

The Millennial generation does not appear to be terribly interested in cars, or even in driving for that matter. A report by CNW Research found that today’s twentysomethings buy just 27 percent of all new vehicles sold in the United States, down from the peak of 38 percent in 1985.116 The report states that roughly one-third of the decline can be attributed to Millennial migration to the used-car market, while the other two-thirds represent an overall decline in driving among the generation.117 In fact, young people aged 16 to 34 drove 23 percent fewer miles on average in 2009 than the same age cohort in 2001—the greatest decline in driving among any age group.118

Companies such as Zipcar, Lyft, and Alta Bicycle Share are capitalizing on smartphone technologies and the Millennial preference for access to goods over ownership of goods.

How much of this trend can be explained by economic circumstance? In an interview with the online publication Automotive News, Mustafa Mohatarem, the chief economist at General Motors, said, “I don’t see any evidence that young people are losing interest in cars. It’s really the economics, and not a change in preference.”119 Mohatarem contends that as Millennials find jobs, shed student loan debt, and start families of their own, they will start purchasing cars. Others are less optimistic.

According to US PIRG, a decline in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) among Millennials began in 2005, three years before the recession hit.120 Another recent study by CNW Research finds that nearly 10 percent of households in the United States are currently carless, compared with only 5 percent two decades ago. CNW says that while the recession may explain some of this behavior, the trend was clear prior to the economic downturn.121

The truth behind the decline in driving and car ownership is likely a combination of these two assessments: It’s true that many Millennials cannot afford vehicles; however, a whole host of other transportation options also make it easier for the generation to opt out. Compared with previous generations, more Millennials live in urban areas, staying closer to work and entertainment. Instead of driving, they access public transportation or ride-share options, walk, or cycle to get from point A to point B.122 While vehicle miles of travel (VMT) declined among 16- to 34-year-olds between 2001 and 2009, the same age cohort took 24 percent more total bike trips and traveled 40 percent more miles on public transportation than their counterparts in 2001.123

Technology, especially the rapid spread of smartphones, is making it easier for Millennials to get around via ride sharing or car sharing. According to the report Digital-age transportation, “New transport models made possible by mobile phones, apps, and smart card technology are taking a good that sits idle most of the time and turning it into something else.”124

Technology, especially the rapid spread of smartphones, is making it easier for Millennials to get around via ride sharing or car sharing. According to the report Digital-age transportation, “New transport models made possible by mobile phones, apps, and smart card technology are taking a good that sits idle most of the time and turning it into something else.”124

Companies such as Zipcar, Lyft, and Alta Bicycle Share are capitalizing on smartphone technologies and the Millennial preference for access to goods over ownership of goods. These companies allow customers to rent cars, bikes, or seats in someone else’s car when they’re needed, instead of shelling out cash or taking a loan to own them personally. It’s a more affordable option. According to AAA’s 2012 “Your Driving Cost” survey, the average annual cost of owning a vehicle is $8,946, compared with the average cost of using Zipcar of $2,085 a year.125

As Millennials age, many—like members of all generations before them since the rise of the mass-produced motor vehicle—will buy cars as soon as they can afford them. Others, however, will likely retain a preference for access over ownership despite their ability to buy a car, and perhaps a new model of technology-driven, app-based, peer-to-peer transportation will flourish in the United States, leading to a host of positive associated health and environmental impacts. The degree to which the generation follows one of these trends will ultimately be determined by their lifestyle choices as they age. A Millennial that lives in a major city, with access to public transportation, for example, may never find use for a personal vehicle, whereas a Millennial in a suburb will almost definitely need one.

Policy impact: Decrease in tax revenue

Millennial driving trends, whether they remain constant or even increase but do not shift back to historical levels, will impact tax revenues at both the federal and state levels. The most notable impact will be on the gas tax. At the federal level, the gas tax is 18.4 cents per gallon. Revenues from the tax support the Federal Highway Trust Fund, which in turn passes the money to states through a series of formula grant programs. The funds are split between accounts that provide subsidies for highway maintenance and construction, as well as mass transit.

The Highway Trust Fund is already in trouble. Without a capital infusion, the CBO predicts that the fund will reach insolvency by 2015. This isn’t the first time it’s needed help: Over the past five years, the federal government has transferred more than $40 billion of general revenue to the Highway Trust Fund to keep it solvent.126 The fund is suffering due to multiple reasons, including the decline in American driving, the rise of fuel-efficient vehicles, and the fact that the tax has not increased in 20 years—not even to adjust for inflation. While the problem is well known, proposals to raise the gas tax or develop other transportation-associated fees have gained little traction in Congress.127

State and local tax implications

States are also impacted by the waning availability of the Highway Trust Fund as they rely on it to support local transportation budgets. While individual states face potential decreases in federal funding, they are also dealing with declining transportation taxes at home. The specific composition and percentage breakdown by funding source varies from state to state; however, most state transportation revenue sources are under stress due to changing trends around driving.128

In addition to gas taxes, some states could suffer further revenue loss from the fall in car ownership among the Millennial generation. For example, states such as Virginia and Rhode Island collect roughly 6 percent of their total own-source revenue from tangible personal property taxes, including taxes on motor vehicles.129 These funds will take a hit if Millennial vehicle consumption does not increase.130 Additionally, declining car sales now and in the future will impact states that rely heavily on sales taxes, such as Washington and Tennessee, where the sales tax comprises roughly 60 percent of revenue.131

Mitigating strategy #1: Creative financing for infrastructure projects

Traditional public-private partnerships

While there is less public financing available for transportation projects, the need for dynamic, modern, and revitalized transportation infrastructure systems are growing across the country. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are one alternative to government funding. PPPs are contractual agreements between public and private sector entities to share the risk and reward of delivering a public service.

PPPs have already funded transportation infrastructure projects in Florida, Indiana, Washington, DC, and Virginia—but only 32 states currently have legislation in place to allow for them.132To facilitate their ongoing and expanded use in future infrastructure projects across the country, states can pass PPP legislation.

Nontraditional public-private partnerships

Beyond conventional ways of leveraging PPPs—entering into partnerships where physical infrastructure is built and maintained by private companies for public good—states and localities can also consider PPPs that leverage private technology. These kinds of partnerships between the private and public sector can make current transportation infrastructure and systems more efficient. With the rise of technology, “almost every aspect of transportation—from electrification of cars and up-to-the minute information for drivers, to ways of reducing the wasted capacity of empty seats in cars and improving the experience of public transit passengers”—could benefit from private sector innovation.133

Mitigating strategy #2: Facilitate the sharing economy

Peer-to-peer transportation services have the potential to provide measureable benefit to cities across the country. Car sharing provides a good example: Every shared car replaces 9–13 owned cars, reducing parking demand and personal vehicle ownership expenses.134 Car sharing can increase citizen mobility without public subsidies, as 50 percent of new car-sharing members do not have access to a vehicle before joining.135 And in some cities, car sharing creates new sources of revenue. In Washington, DC, for example, the city auctioned 84 curbside parking spots to three different car-sharing companies, for nearly $300,000 in profit.136

Yet at present, approaches to regulating the industry are, in many cities, disjointed at best and punitive at worst.137 In Seattle, differing standards across the driver-for-hire industry are creating tension between city officials and the taxi unions. The city requires written exams, expensive insurance, special licenses, and criminal background checks for cab drivers, but there are no requirements to become a Lyft driver.138 The city of Los Angeles has issued cease-and-desist orders for car-sharing companies, while the city of Philadelphia has impounded car-share vehicles.139

Car and ride sharing are likely to persist in some way, whether they completely disrupt the transportation industry or continue to predominantly serve broke college kids and twentysomethings in need of a cheap or convenient ride. Localities should embrace rather than fight the trend and help the sharing economy flourish through sharing-friendly policies. Simple policy changes, already taking place in cities such as San Francisco and Washington, DC, can make a big difference. Cities can consider creating designated car-share parking in public parking spots, expanding high-occupancy vehicle lanes to allow for increased car sharing, and allowing rental of unused residential parking spots to car-share vehicles to enable a sharing-friendly environment while capturing the social and economic benefits.140

Consumer realities: Declining homeownership

Millennials are not buying houses at the same rate as generations past. Only 9 percent of 29–34-year-olds entered a first-time home mortgage agreement during 2009–11, compared with 17 percent a decade earlier.141 Homeownership rates among Americans under the age of 35 are currently at 36.5 percent, compared with 41 percent two decades ago.142

Various explanations account for the fall in homeownership among young adults in the United States, many relating directly to the housing bust of 2007 and the Great Recession that followed. Since the days of the subprime “NINJA” (no income, no job, no assets) loans, lending standards are more stringent. Today, purchasing a home requires a down payment, a good debt-to-income ratio, and a solid credit score143—three things many Millennials do not have.144

High levels of unemployment and underemployment, coupled with high levels of student loan debt, are problematic in both saving for a down payment and meeting debt-to-income requirements. In addition, high levels of debt (and default on debt) lower credit scores, a problem that especially affects younger people who have had less time to build credit and often less time to recover from past credit transgressions. The average credit score among all 20–29-year-olds is 638145—considered “poor” and about 80 points shy of the 720 needed to qualify for a private mortgage without public assistance.146

The intangibles

In addition to financial constraints, there are less tangible disincentives to Millennial homeownership. Many Millennials no longer see the investment value in buying a house in the same way their parents did.147In an interview, author David Burstein explained that “Millennials don’t feel the fundamental argument for buying a home is the same anymore.”148 While Burstein believes some of the change in homeownership can be attributed to the economy, he contends that the Millennial generation is also fundamentally redefining an American dream that doesn’t necessarily include owning a house or car. Others believe Millennials, one-third of whom move to a new residence every year, are simply too transient to buy into homeownership.149 This is attributed to the Millennial preference for seizing opportunities and experiences; however, many Millennials are also moving from place to place in order to secure employment opportunities.150

By preference or necessity, Millennials could conceivably be a generation of renters, favoring the freedom and flexibility associated with renting over the stability and investment value historically associated with homeownership. And maybe that’s not such a bad thing over the long term. On declining homeownership, Georgetown economist Dr. Holzer echoed the views of many economists and policy analysts following the Great Recession, observing, “If this is a long-term trend . . . it might actually be healthy. Americans put too much of their resources into homeownership. If some savings were redirected to more liquid assets, that would be a good thing.”151

By preference or necessity, Millennials could conceivably be a generation of renters, favoring the freedom and flexibility associated with renting over the stability and investment value historically associated with homeownership. And maybe that’s not such a bad thing over the long term. On declining homeownership, Georgetown economist Dr. Holzer echoed the views of many economists and policy analysts following the Great Recession, observing, “If this is a long-term trend . . . it might actually be healthy. Americans put too much of their resources into homeownership. If some savings were redirected to more liquid assets, that would be a good thing.”151

Sociological changes driving a longer-term trend

The current trend in Millennial homeownership could certainly still change as the generation settles into marriage and families. The decline in young homeowners, while exacerbated by the Great Recession, began more than two decades before the economic downturn. Between 1980 and 2000, the share of people in their late 20s buying homes declined from 43 percent to 38 percent. The share of people in their early 30s buying homes declined from 61 percent to 55 percent.152 Changing sociological trends around family formation are often cited to explain this longer-term shift.

The average credit score among all 20- to 29-year-olds is 638—considered “poor” and about 80 points shy of the 720 needed to qualify for a private mortgage without public assistance.

In the paper “Why has homeownership fallen among the young?,” economists Jonas Fisher and Martin Gervais show that marriage and homeownership are so closely linked that a decline in marriage rates invariably lowers homeownership rates.153Couples with children are also more likely to be homeowners than those without children.154 Since the Millennial generation is delaying both marriage and childbearing, it is reasonable to assert that it is delaying homeownership too.

The majority of Millennials claim they have no intention of putting off homeownership forever. One recent survey found that 93 percent of 18–34-year-olds plan to own a home someday.155 A similar survey by Fannie Mae found that 90 percent of respondents aspired to be homeowners in the future.156 In the event Millennials do become a generation of homebuyers, the question remains: Will they want the suburban housing stock their Boomer parents will need to cash in on for retirement?

Millennial preferences

The “great senior sell-off” is about to hit the United States. This phrase refers specifically to the impending retirement of the Boomer generation and the associated sale of its suburban, single-family homes in order to pay for retirement.157 Unfortunately, Millennial housing preferences may not align with the housing supply of large, expensive houses built by the Boomers in the height of the real estate boom of the 1990s and 2000s. While the market will eventually adjust to meet shifting preferences, it will take time and could result in declining values for Boomer homes.

A recent study by the Urban Land Institute found that Millennials value proximity to public transportation, walkability, and mixed-use communities, and prefer to live in large to mid-sized cities. In the report, 39 percent of Millennial respondents said they wanted to live in a city, compared with only 17 percent who reported wanting to live in the suburbs.158 Though the numbers vary by survey, some reports find as many as 77 percent of Millennials would prefer to live in an urban core over a suburban area.159

RAND Corporation economist Dr. Matthew Hill touched on another potential obstacle to Millennials buying the houses built by the Boomer generation. In an interview, Dr. Hill said, “We’re seeing a decline in consumption and a desire to live more modestly among young people. If this continues, whether people live in cities or suburbs, we will see people living with less, in smaller spaces.”160 A recent survey by Better Homes and Gardens Real Estate confirms that Millennials aren’t looking for big luxury homes like those their parents built: 77 percent of respondents reported they would prefer a house that had only the essentials over a luxury home.161

Some argue the Millennials’ adoration of close quarters and urban living is ephemeral: Once married with children, they say, the Millennial generation will flee to the good schools and big backyards of the suburbs. While it’s hard to predict the way that Millennial housing preferences will change in the future, financial constraints may keep many Millennials from purchasing the homes of their parents’ Baby Boomer generation in the near term, irrespective of preference.162

Policy impact #1: Increased demand for federal housing assistance

Homeownership

Regardless of which Millennial housing trends persist, there will likely be increased demand for public housing assistance in the future. Poor credit scores, high debt-to-income ratios, and stagnating incomes—economic realities many Millennials currently face—will make qualifying for private mortgages difficult, even as the generation approaches its early 30s.

Of Millennials who want to buy houses, whether in cities or suburbs, many will need help from the Federal Housing Administration, which secures private-mortgage financing for riskier buyers by assuming some of the risk a bank would otherwise hold. The type of homes Millennials decide to buy and the rate at which their financial situations improve will be major determinants of future demand for federal home-buying assistance.

Affordable rentals

Already in short supply since the housing crisis, demand for affordable rental options could be exacerbated if more Millennials choose to act on the intentions stated in surveys by turning to rentals in larger percentages, even if this itself turns out to be only an extended period of renting before ultimately opting to purchase housing. Rental prices are on the rise in most local markets and are expected to continue upward.163 With low supply and high demand, landlords and property managers can be choosy when selecting renters—checking credit history, income, and debt to find the best candidates. Additionally, privately owned, unsubsidized, affordable rental units, which might be a next-best option, are also a dwindling asset.164

While already a point of focus for federal housing officials, the rental squeeze may be worse than anticipated due to the potential for high Millennial demand and their low ability to pay. In the event that Millennials continue to flood the rental market and are unable to secure affordable housing, there might be increased demand for public assistance to make housing more affordable. The private sector will likely adapt housing supply to meet consumer demand in the long run; however, federal incentives for expansion of the private affordable rental housing stock could speed up the process.165

Mitigating strategy #1: Standardize rent-to-own agreements

Rent-to-own agreements allow prospective buyers to sign multiyear leases and pay a higher monthly rent to a homeowner under a contract that stipulates a portion of the rent will go toward future purchase of the property.166 Expanding access to rent-to-own housing options might alleviate credit concerns and increase access to homeownership among the Millennial generation.

Contract terms vary on rent-to-own arrangements, but they are often two to five years in length and end with an option for the renter to buy the home at a predetermined price, minus the equity they have gained through payments during the contract period. In the event the renter decides not to buy the home, the homeowner keeps all money paid over the contract period—both the regular rent money and the additional money paid toward the future purchase of the home.167

Rent-to-own agreements can have benefits for both homeowners and prospective buyers. Homeowners can lock in a prospective buyer at a predetermined price and under specific contract terms up front. At the same time, prospective buyers can use the period of the contract to build up their credit while gaining equity in the home they are renting. There are drawbacks too, though, as both homeowners and renters can suffer in the event the contract terms are not explicit and fair to both parties.

While growth in this sector of the real estate market might have significant benefits given the current realities faced by many Millennials, it will also require scrutiny and consumer protection to ensure transactions are fair to all parties involved.168 The Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB), established to ensure consumers have access to information on fair financial practices and to enforce federal consumer financial laws, could help by issuing reports on rent-to-own trends and publishing best-practice guidelines for the rent-to-own industry.169 By providing more information, the CFPB can help create, socialize, and enforce fair standards for rent-to-own agreements.

Mitigating strategy #2: Partner to increase availability of affordable rental housing

While the nation is in great need of affordable rental housing, public funding to support building these properties is strained. To make up for the shortage in public financing, the government could turn to PPPs, which could effectively increase the availability of affordable rental homes at minimal cost to the public by leveraging private sector funding. This is already being done by some organizations across the country.170

One such organization, Enterprise Community Partners, works with financial institutions, governments, and community organizations to increase affordable housing options in communities across the country. Over the last 30 years, it raised and invested $14 billion to help preserve 300,000 affordable rental and for-sale homes in the United States.171 Organizations like Enterprise Community Partners could be of significant assistance to the rental market moving forward and should be considered a primary means of supporting government housing solutions.

Conclusion

The road to the future holds both significant challenges and boundless opportunities for the Millennial generation. Unemployment, underemployment, and student loan debt create real constraints for the generation from the outset of their adult lives. Research conducted for this paper indicates that the average college-educated young couple starts their lives roughly $360,000 behind past generations due to these burdens. But public-private partnerships, technological advancements, and new financial models are enabling exciting changes across the economy. Government can be a leader in leveraging these innovations for public good.

Through small policy adjustments, the public sector can clear the path for Millennial progress, to the benefit of federal, state, and local governments. Modest investments in employment programs can help Millennials get a foothold in the job market at a critical point in their lives. The expansion and replication of mutually beneficial partnerships between the public and private sectors can jump-start local economies, update the nation’s transportation infrastructure, and revitalize the US housing stock.

Additional policy changes bring little or no cost to government. Adjustments to the Small Business Administration’s loan portfolio could help Millennials build credit and businesses. Simplification of federal student loans could help the generation manage its debt while bolstering timely repayments to the government. Mandated changes to credentialing in higher education could make education more affordable and accessible in the future. Better information and standard guidelines for new ways to finance homeownership could help open the housing market to a new segment of the population.

The Millennials will write their chapter of history in the years to come, and, despite well-documented challenges, the generation is pretty optimistic about its prospects for success. Millennials—both employed and unemployed—believe overwhelmingly that they will do well enough to live out the American dream.172 Perhaps this is youthful naiveté—or maybe this new generation will simply redefine what it means to live a successful and fulfilling life. In either event, government can help clear the path forward and increase the chances for a Millennial success story.

About GovLab

GovLab is a think tank in the Federal practice of Deloitte Consulting LLP that focuses on innovation in the public sector. It works closely with senior government executives and thought leaders from across the globe. GovLab Fellows conduct research into key issues and emerging ideas shaping the public, private, and nonprofit sectors. Through exploration and analysis of government’s most pressing challenges, GovLab seeks to develop innovative yet practical ways that governments can transform the way they deliver their services and prepare for the challenges ahead.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.