2016 Deloitte-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study has been saved

2016 Deloitte-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study State governments at risk: Turning strategy and awareness into progress

21 September 2016

For state governments, many challenges of managing cyber risk—in both funding and talent—have persisted over the years. Yet states have also made progress, as governor-level awareness rises and CISOs make strides in collaborating with other government agencies.

Foreword

Today, no one disputes that state governments need to be concerned with cyber risk. The 2016 Deloitte-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study shows that cyber risk has risen in importance in the eyes of governors and other state executives. For CIOs and CISOs, this governor-level attention is encouraging news and an opportunity to secure resources and support for state cybersecurity programs.

Given its current trajectory, cyber risk in state governments is unlikely to dissipate, and may even grow—largely a result of the increase in innovation and use of technology and data. State governments have rapidly adopted new technology to better serve constituents and reduce dependency on legacy systems that are difficult to maintain. Ironically, the very steps governments have taken to embrace these new innovations add to the cyber risks. This is why we need to begin viewing the management of cyber risk as a core function of running government operations.

Since 2010, Deloitte and NASCIO have been conducting biennial surveys of CISOs and state officials to explore how states are managing cyber risk. In our fourth survey to date, we found that even as the importance of cybersecurity has gained ascendancy, many of the issues CISOs are grappling with are stubbornly persistent. Following are some of the top takeaways from the 2016 survey:

Governor-level awareness is on the rise. The survey results indicate that governors and other state officials are receiving more frequent reports from CIOs/CISOs. Initiatives such as the National Governors Association (NGA) “Call to Action” seem to be helping to maintain the prominence of cybersecurity on executive agendas.

Cybersecurity is becoming part of the fabric of government operations. For the first time, all respondents report having an enterprise-level CISO position. The CISO role itself has become more consistent in terms of responsibilities and span of oversight. CISOs are also focusing their energies more on what they can control.

A formal strategy and better communications lead to greater command of resources. Securing sufficient resources—both funding and talent—remains a top challenge for CISOs. This year, we found evidence that states that take a proactive approach to strategy setting and communication are more likely to see improvements in funding and access to talent.

We believe that, overall, the survey results spell out a clear message for CISOs: State leaders are paying attention. Take advantage of this focus to make substantial progress.

Finally, we would like to thank participants in this year’s survey: the 49 CISOs who responded to the longer version of the survey—24 of whom were new to their role—and the 96 state officials who responded to the accompanying state officials survey. Your time and commitment will help states in their efforts to effectively manage cyber risk and protect citizen data.

The authors of the survey,

Doug Robinson

Executive Director

NASCIO

Srini Subramanian

Principal

Deloitte & Touche LLP

Governor-level awareness is on the rise

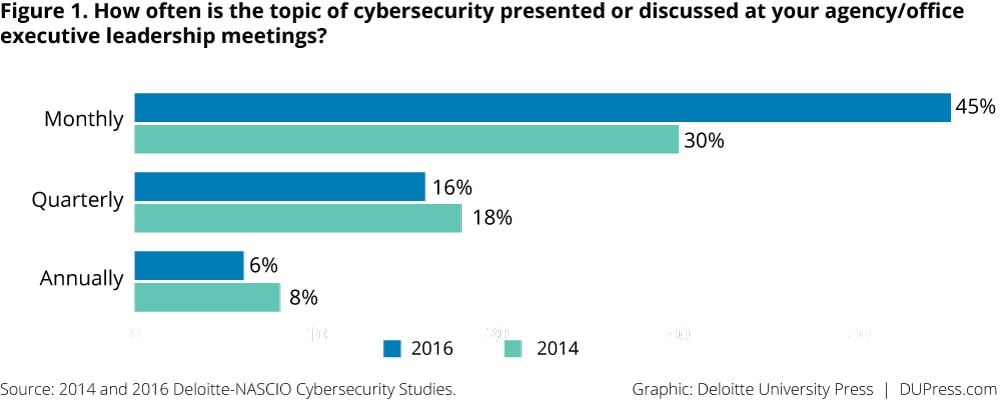

The critical nature of cybersecurity has not been lost on governors and other state officials. The state officials survey this year shows that over 90 percent say that cybersecurity is important to their state, and over 94 percent say that it is important to their individual agency. Cybersecurity is also a more frequent topic of discussion at state executive leadership meetings (figure 1). More than three-fifths (61 percent) of state officials say that cybersecurity is discussed at executive leadership meetings at least quarterly, if not monthly, compared with less than half (48 percent) in 2014.

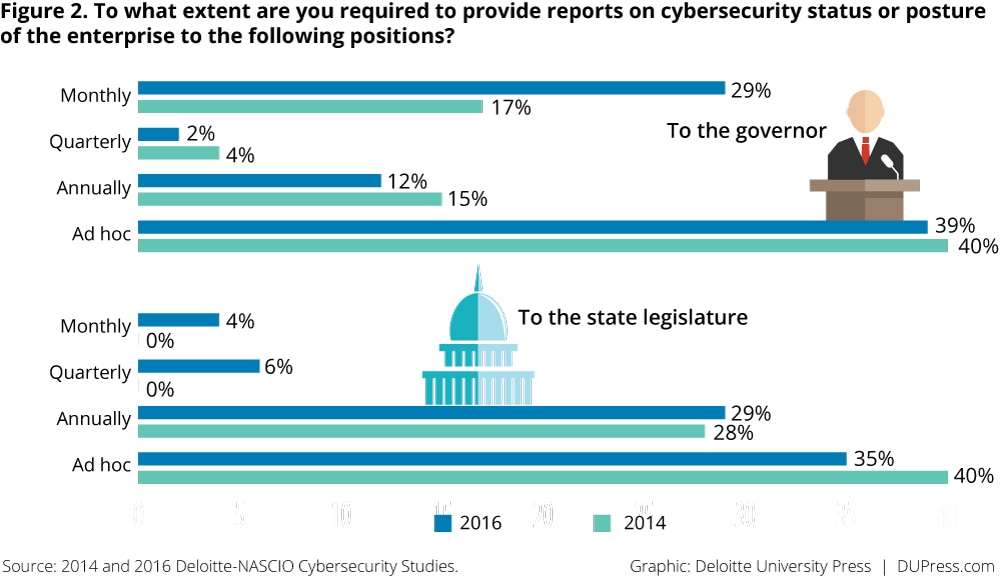

Governors are receiving more frequent briefings on cybersecurity. Nearly a third (29 percent) of CISOs provide their governors with monthly reports on cybersecurity, compared with only 17 percent in 2014 (figure 2). However, this level of communication has not extended to state legislatures. Nearly a third of respondents say that they never communicate with their legislatures, unchanged from 2014. This is an important consideration, given the legislature’s role in appropriating funds.

Despite increased executive-level awareness of cybersecurity, there remains a “confidence gap” in terms of how well CISOs versus state officials think security threats can be handled by their states. For instance, two-thirds (66 percent) of state officials say they are very or extremely confident that adequate measures are in place to protect information assets from externally originating cyber threats, compared with only a quarter (27 percent) of CISOs. These findings, which are similar to those from our 2014 study, indicate that CISOs may need to take a different approach when communicating the severity of cyber threats to state officials.

States are also starting to act and make progress in areas visible to governors. Since the NGA issued its “Act and Adjust: A Call to Action for Governors for Cybersecurity” in 2013, more than half (54 percent) of respondents say that they have implemented at least some of the NGA’s recommendations, compared with only a third (33 percent) in 2014 (figure 3). In fact, governors have launched initiatives ranging from state cyber academies and public-private partnerships to dashboards and preparedness and response plans.1

See survey analysis section for more data.

Cybersecurity is becoming part of the fabric of government operations

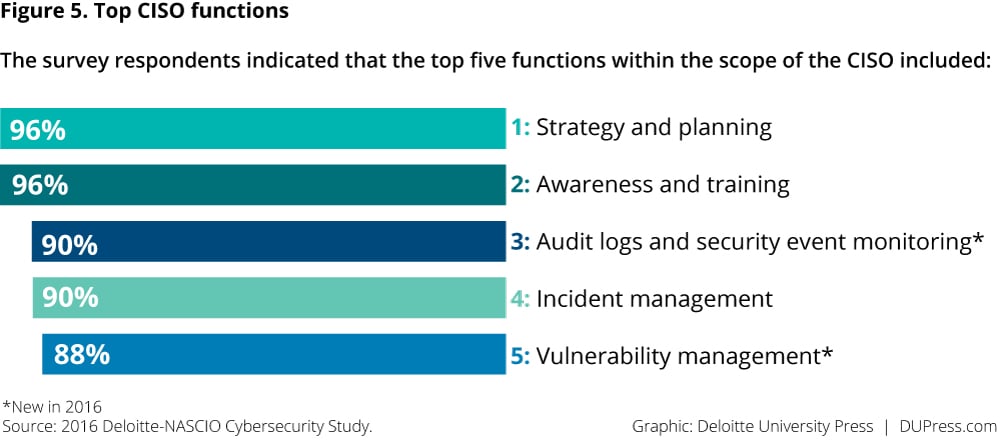

CISOs have begun to take a more programmatic approach to managing cyber risk and are starting to concentrate on areas that are in their control (figure 4). Only 45 percent of CISOs cited the "growing sophistication of threats" as a barrier to addressing cybersecurity challenges, down from 61 percent in 2014. CISOs are focusing on areas where they can take proactive steps to better manage risks. Some of the top areas CISOs say are within their purview include audit logs and security event monitoring, strategy and planning, and vulnerability management (figure 5).

The CISO role itself is now a well-established position in state government. For the first time, all respondents report having an enterprise-level CISO position, an indication that states consider protecting information assets—including citizen data—from cyber threats to be an important government responsibility. CISOs’ responsibilities and top priorities have remained consistent over the past two years, a sign that the role is solidifying. This conclusion is supported by the fact that some 50 percent (24 individuals) are new to the role—yet they say their responsibilities are the same as those who have held their position for several years.

In terms of priorities, three initiatives that made the top five—training and awareness (39 percent), monitoring and SOCs (37 percent), and strategy (29 percent)—were also among the top five in 2014 (figure 4).

The mechanisms by which CISOs’ authority over other organizational entities is established have not changed significantly since 2014. In addition, alignment of cybersecurity initiatives with business initiatives has increased, with 29 percent of respondents reporting appropriate alignment, versus only 14 percent in 2014. However, we continue to see CISOs have challenges in making progress on enterprise-wide initiatives in a largely federated model of governance with the agencies. For example, our results show challenges in operationalizing state-wide identity and access management (IAM) implementations. To overcome these challenges and help close the confidence gap that we continue to see, more will need to be done to elevate the authority and influence of the CISO role. CISOs need to improve communications around risks and metrics to better inform agency business executives and help promote their agendas.

See survey analysis section for more data.

A formal strategy can lead to more resources

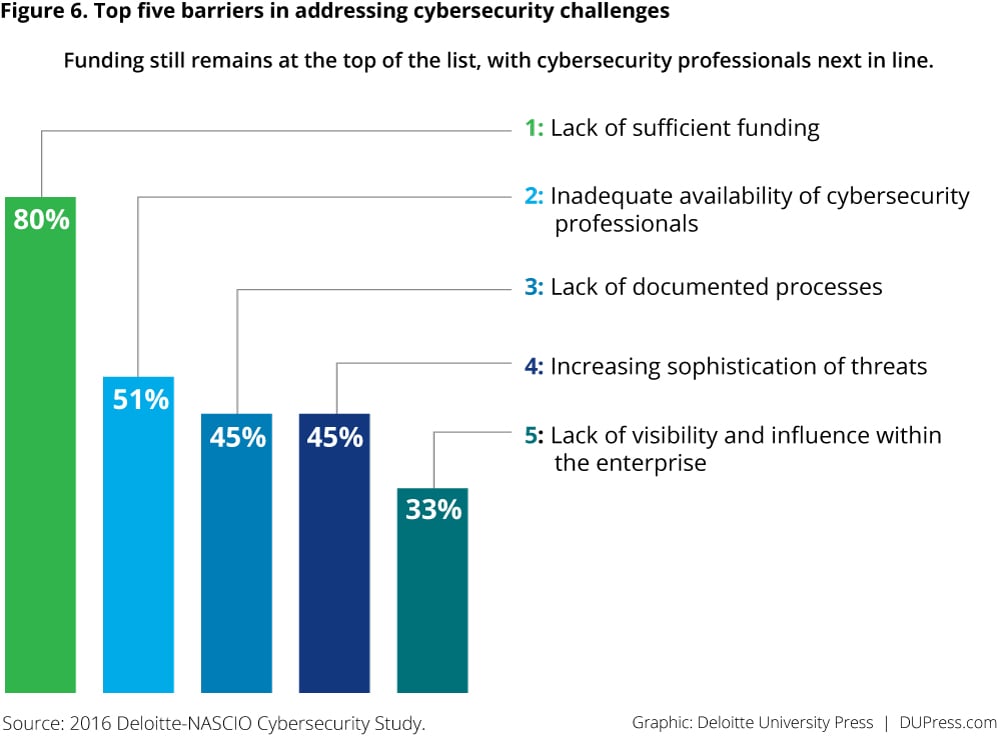

Even as CISOs better define their roles and become an integral part of state government, they continue to face challenges, particularly in securing the resources they need to combat ever-evolving cybersecurity threats. Four-fifths (80 percent) of respondents say inadequate funding is one of the top barriers to effectively address cybersecurity threats, while more than half (51 percent) cite inadequate availability of cybersecurity professionals (figure 6).

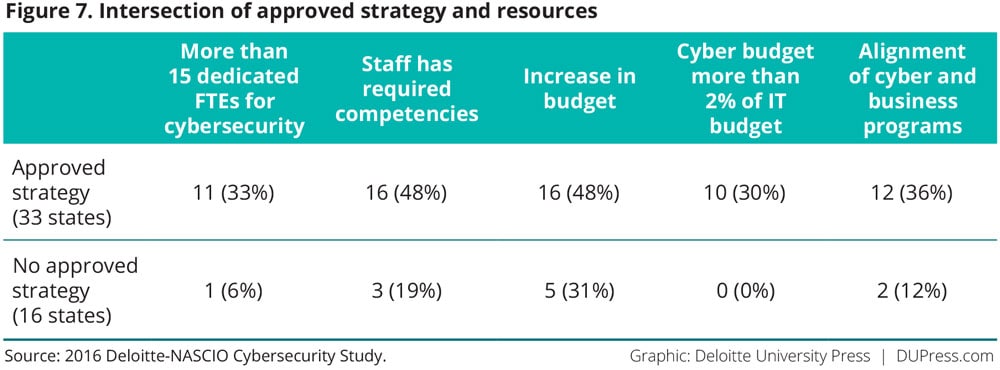

Survey evidence suggests that when CISOs develop and document strategies—and get those strategies approved—they can command greater budgets and attract or build staff with the necessary competencies. A direct correlation can be seen between having an established strategy and obtaining more full-time equivalents (FTEs) dedicated to cybersecurity, as well as year-over-year budget increases (figure 7). For example, 11 out of 33 states that have an approved strategy also reported they have more than 15 FTEs dedicated to cybersecurity, and 16 out of 33 states with an approved strategy reported they also had an increase in budget. An approved and proactively communicated strategy can also help CISOs overcome another barrier: “lack of visibility and influence in the enterprise,” an ongoing challenge in the largely federated governance model in state government.

See survey analysis section for more data.

Key takeaways overview

Survey data analysis

In the following section, we take a detailed look at the survey findings.

Strategy and governance

Strategy is central to driving states’ cybersecurity direction, which makes it especially important for CISOs to push for approval of their strategies. This year’s survey shows that more CISOs are making progress in this regard: Two-thirds (67 percent) had cybersecurity strategies that were both documented and approved, compared with 55 percent in 2014 (figure 8). From a governance perspective, most states’ security functions use a largely federated model of governance, which makes it even more important for CISOs to be effective in influencing agency business and technology stakeholders and getting their buy-in for the strategy.

Strategy is central to driving states’ cybersecurity direction, which makes it especially important for CISOs to push for approval of their strategies. This year’s survey shows that more CISOs are making progress in this regard: Two-thirds (67 percent) had cybersecurity strategies that were both documented and approved, compared with 55 percent in 2014 (figure 8). From a governance perspective, most states’ security functions use a largely federated model of governance, which makes it even more important for CISOs to be effective in influencing agency business and technology stakeholders and getting their buy-in for the strategy.

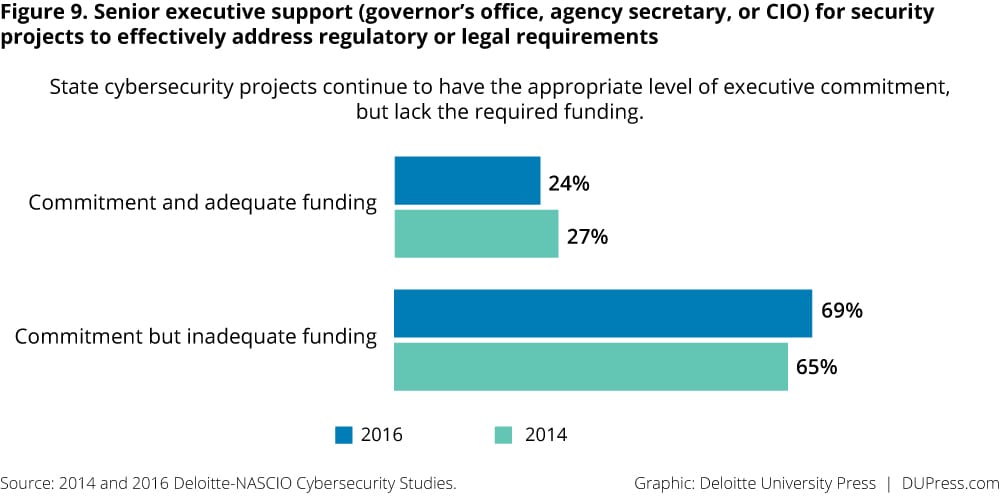

Strategies continue to involve both lines of business and technology decision makers; however, significant confidence gaps continue from the 2014 study, signifying that improvements need to be made in defining the priorities, risks, and strategies in place. A disconnect can also be seen between senior-level commitment and adequate funding (figure 9).

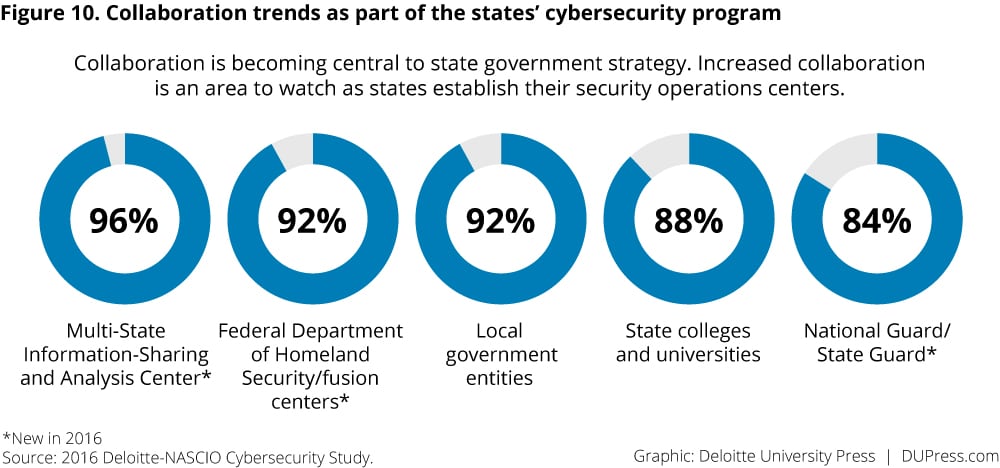

Collaboration across state lines and with federal agencies is also part of respondents’ strategies, and it is an important means of sharing practices for addressing cybersecurity challenges (figure 10). This year, almost all respondents say that they are collaborating with the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MS-ISAC) and the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) fusion centers.

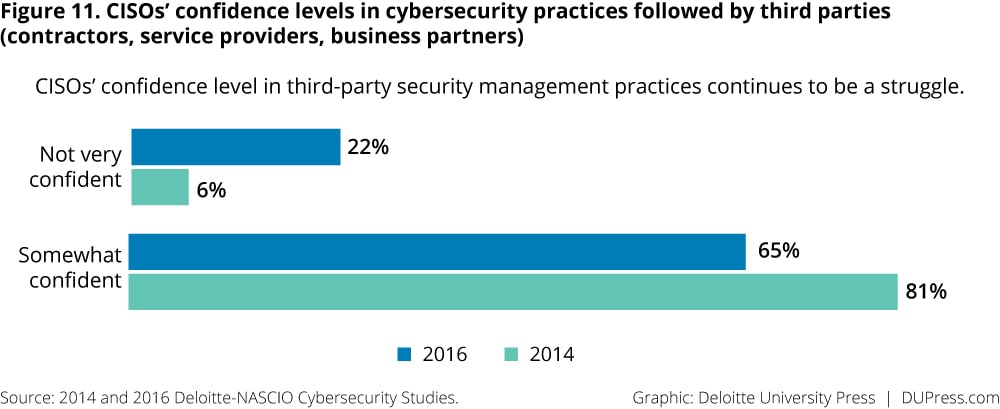

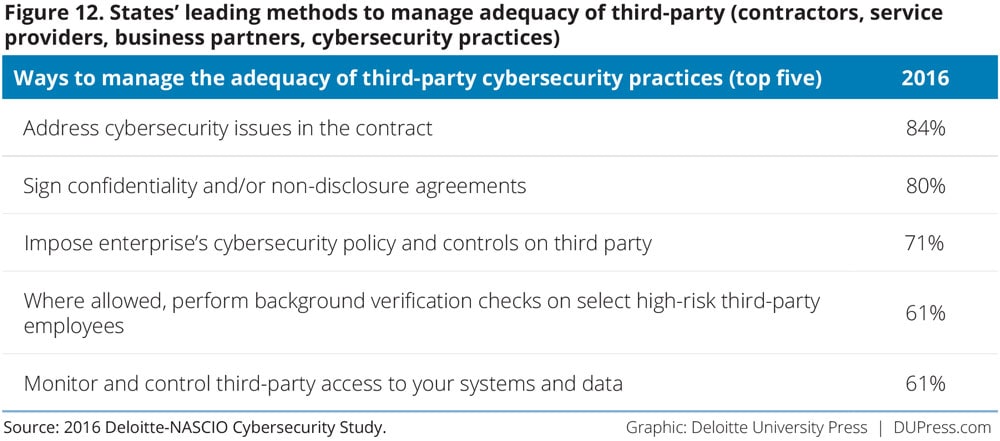

CISOs are expressing a growing concern about the security practices of third parties, including those of contractors, service providers, and business partners. Nearly a quarter (22 percent) of CISOs say they are not very confident in this regard (figure 11). CISOs indicate that addressing cybersecurity in the contract is their leading option for managing the cybersecurity practices of third-party organizations (figure 12).

Budget and funding

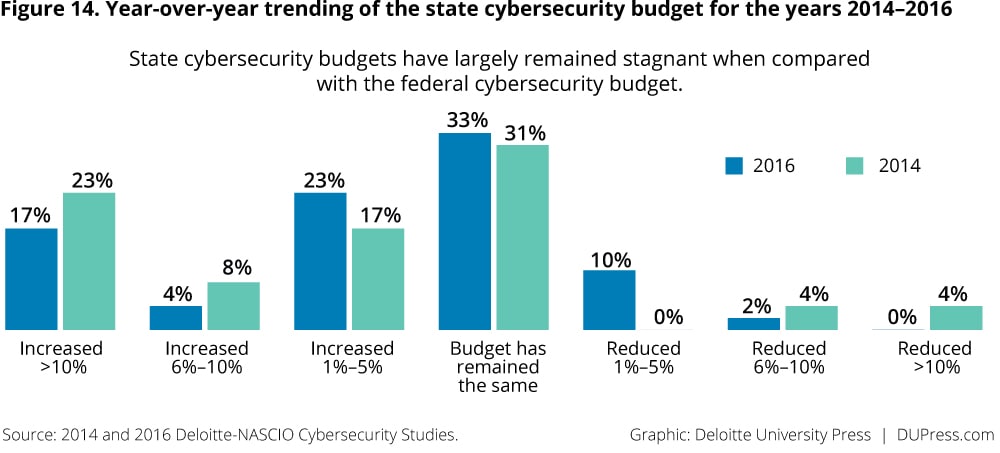

Lack of sufficient funding remained the most significant challenge for CISOs in 2016. The majority of respondents continue to indicate that their cybersecurity budgets were only between 0–2 percent of their state’s overall IT budget (figure 13). The results did show an increase over 2014 in the 3–5 percent range of the state’s overall IT budget. From a year-over-year budget perspective, 33 percent of respondents note that their budgets have remained the same (figure 14). Of the 43 percent of respondents with an increase, most of them noted increases only in the 1–5 percent range. In contrast, the federal cybersecurity budget has seen an increase of 35 percent over the 2016-enacted level.2

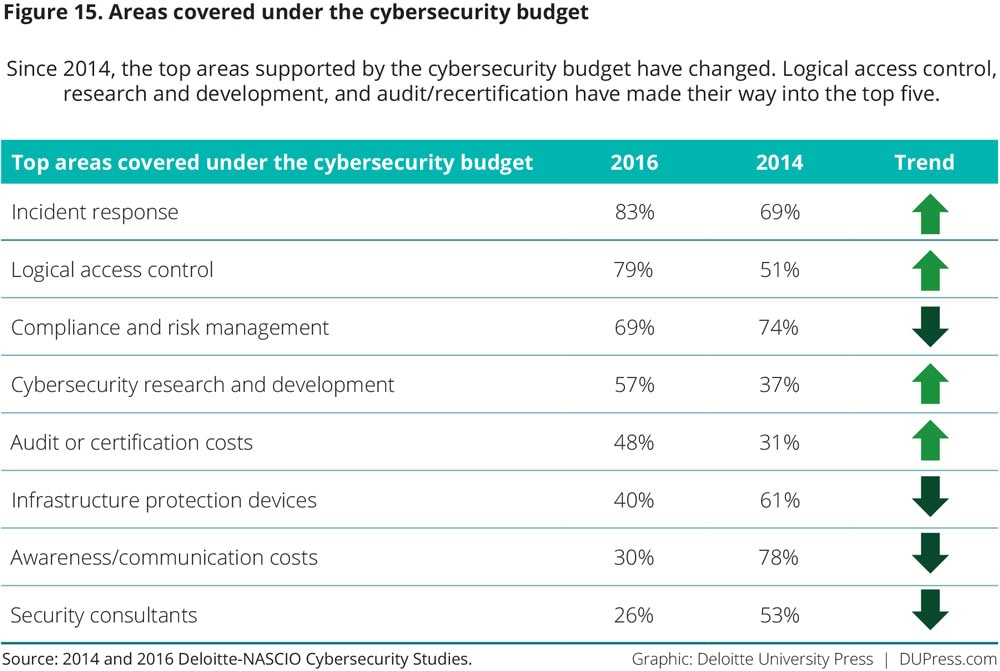

Looking at the top items covered within a budget, this year’s survey shows incident response as the most frequently cited (figure 15). Cybersecurity research and development and audit and certification costs moved up significantly from 2014.

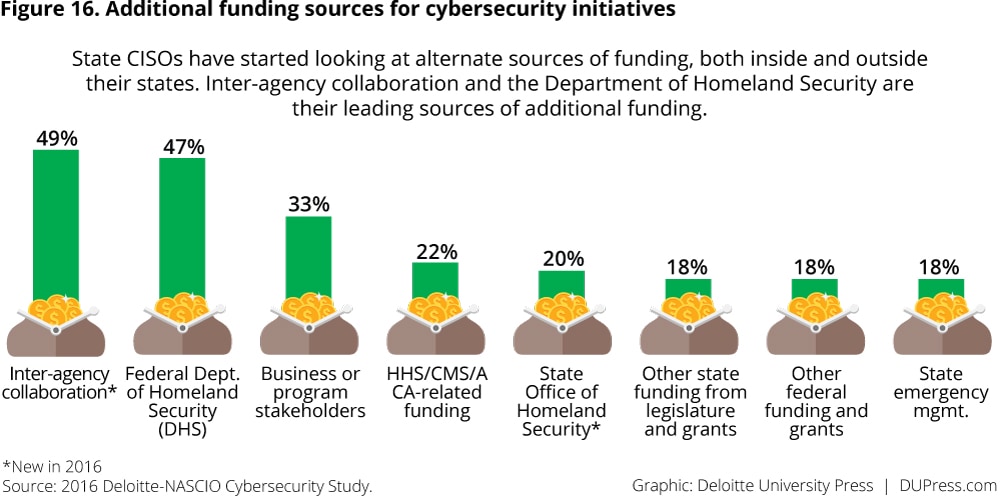

Given cybersecurity’s status as a national issue, states are able to tap into a range of state and federal programs and initiatives to secure additional funding (figure 16). Although limited, these are important avenues for CISOs as they build strategies to bridge the funding gap.

Talent

In 2016, the cybersecurity talent crisis continues. Overall, the size of state cybersecurity staff moved up slightly, consistent with budgets (figure 17)—but not to the levels seen in the private sector or at federal agencies, which may have well over 100 FTEs handling cybersecurity. CISOs cite the inadequate availability of cybersecurity professionals as one of their biggest challenges, second only to obtaining sufficient funding, and note salary and competition with the private sector as the top factors negatively impacting their workforce strategies (figure 18).

For many CISOs, their challenges are exacerbated by underfunded pension plans and budget constraints that have forced states to change retirement plans for those now entering the workforce. Attractive benefit plans, historically one of the “carrots” of a state government career, are no longer a given, and retirement packages are being restructured to more closely resemble those found in the private sector.3 In addition, private sector salaries for information security professionals have risen dramatically in recent years, making state government less competitive on the compensation side.

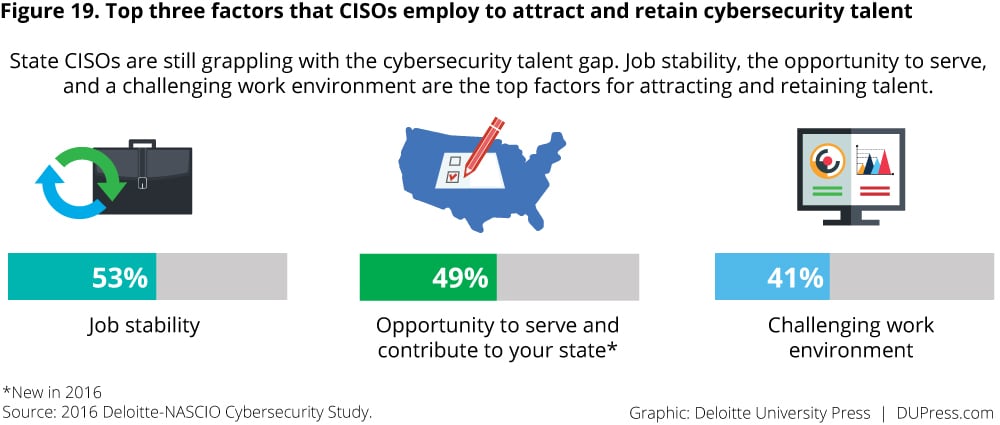

CISOs are therefore looking for other ways to win the hearts and minds of prospective employees. While more than half say that job stability is one of the top three ways to attract and retain cybersecurity talent, nearly as many point to the opportunity to serve as an important factor as well (figure 19). Promoting the potential to “give back” may be an especially effective way to attract Millennial talent, and should be built into talent acquisition plans.

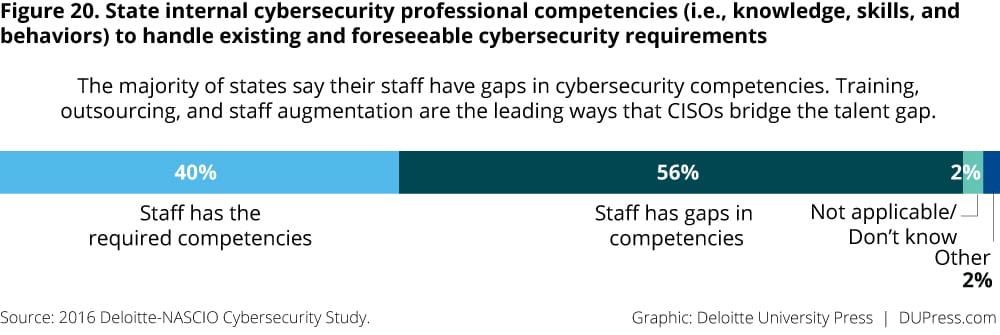

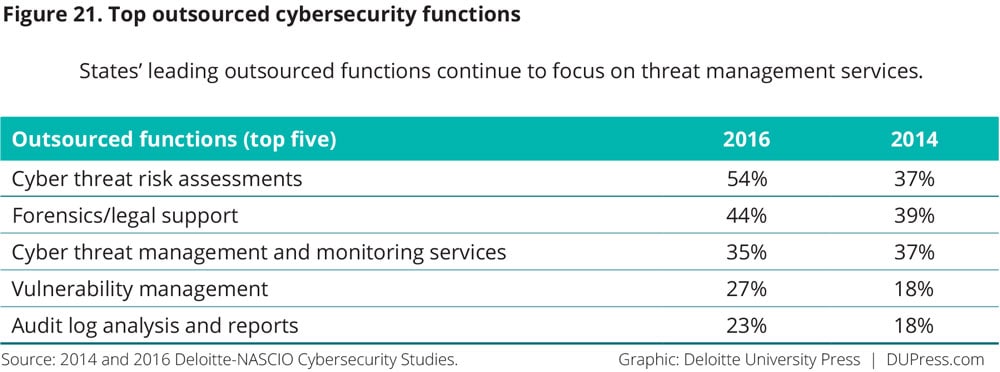

The majority of states (56 percent) see a gap in required competencies (figure 20). To close the cybersecurity competency gap, states are using a range of strategies, including providing training, enlisting outside specialists, and outsourcing certain functional areas (figure 21). Training and awareness, the top initiative reported by states in 2016, has improved since 2014, with more respondents saying that they train a broad range of employees, from systems administrators and programmers to executives and those handling sensitive information (figure 22).

Emerging trends

Identity and access management (IAM)

Identity and access management (IAM)

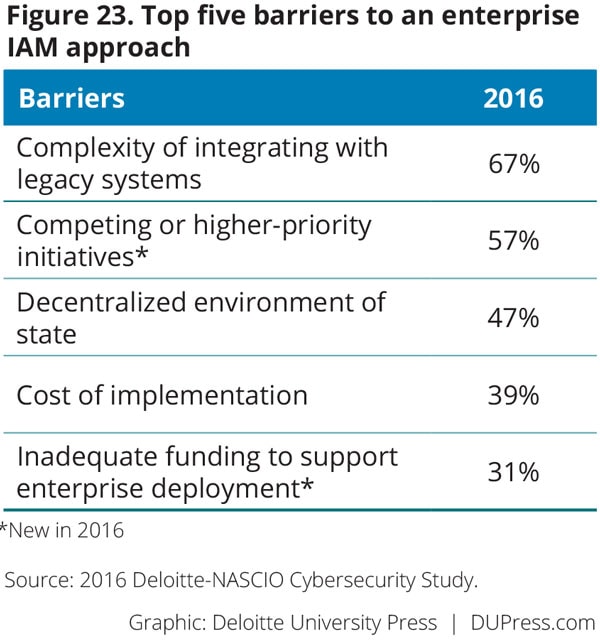

More states in 2016 (47 percent) than in 2014 (33 percent) have an enterprise IAM solution that covers some or all of the agencies under the governor’s jurisdiction. However, CISOs continue to face the same barriers to implementing enterprise IAM solutions, including the complexity of integrating with legacy systems, cost, competing or higher-priority initiatives, and the states’ decentralized IT environment (figure 23). Similar to 2014, CISOs are focusing on implementation of multifactor authentication, federated IAM, and privileged identity management solutions. Cloud-based IAM solutions and citizen identity proofing solutions follow closely as leading initiatives (figure 24).

More states in 2016 (47 percent) than in 2014 (33 percent) have an enterprise IAM solution that covers some or all of the agencies under the governor’s jurisdiction. However, CISOs continue to face the same barriers to implementing enterprise IAM solutions, including the complexity of integrating with legacy systems, cost, competing or higher-priority initiatives, and the states’ decentralized IT environment (figure 23). Similar to 2014, CISOs are focusing on implementation of multifactor authentication, federated IAM, and privileged identity management solutions. Cloud-based IAM solutions and citizen identity proofing solutions follow closely as leading initiatives (figure 24).

Cyberthreats

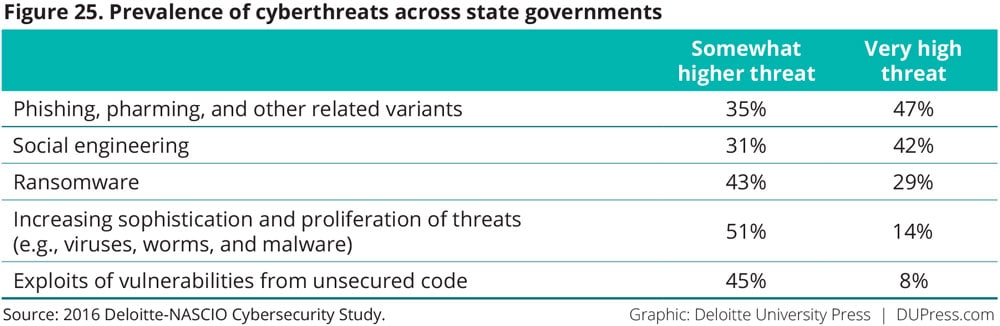

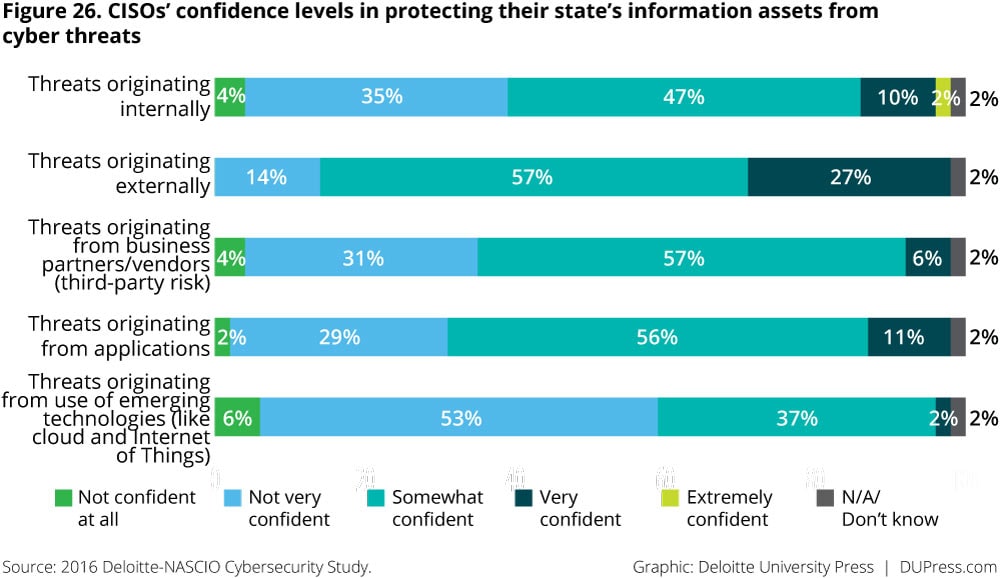

CISOs view threats targeted at employees—including phishing, pharming, social engineering, and ransomware—as likely to be the most prevalent in the coming year (figure 25). This is a change from 2014, when attacks exploiting various vulnerabilities and foreign-sponsored espionage topped the list. CISOs continue to be “somewhat confident” in their states’ abilities to protect against cyberthreats (figure 26). They appear most confident in their ability to protect against internal threats and least confident when it comes to threats originating from emerging technologies.

Assessments

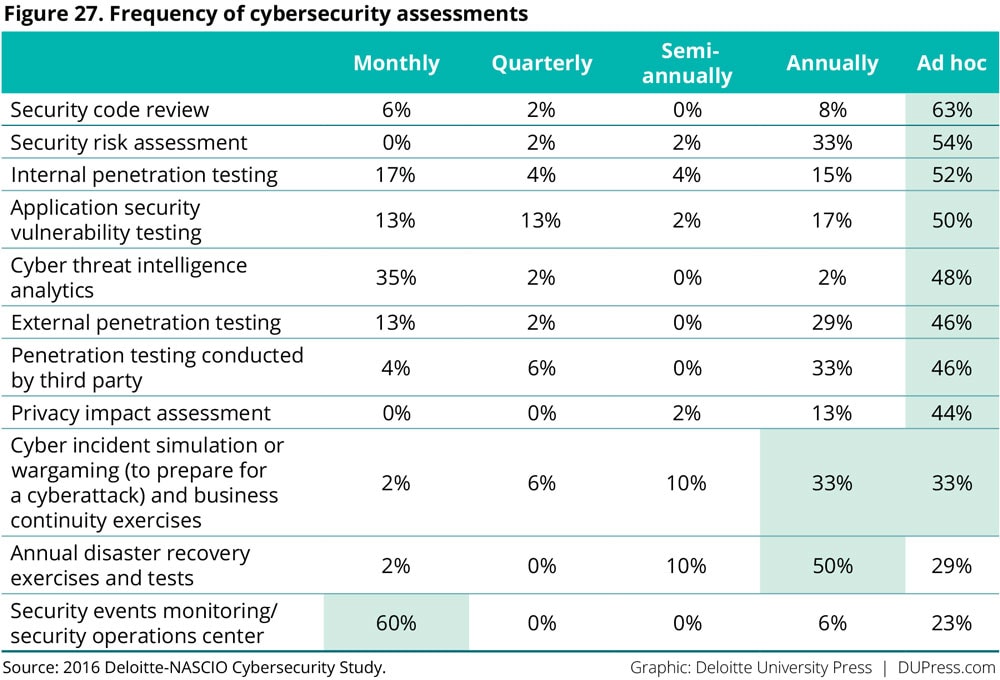

The majority of the states continue to perform ad-hoc assessments to evaluate their cybersecurity posture (figure 27). More frequent assessments could provide a better baseline for determining the effectiveness of cybersecurity controls.

Cybersecurity technology adoption

More states have adopted traditional cybersecurity solutions, such as firewalls and antivirus software (figure 28). CISOs indicate that security compliance, network behavior analysis, data protection, and IAM solutions lead the next wave of enterprise adoption.

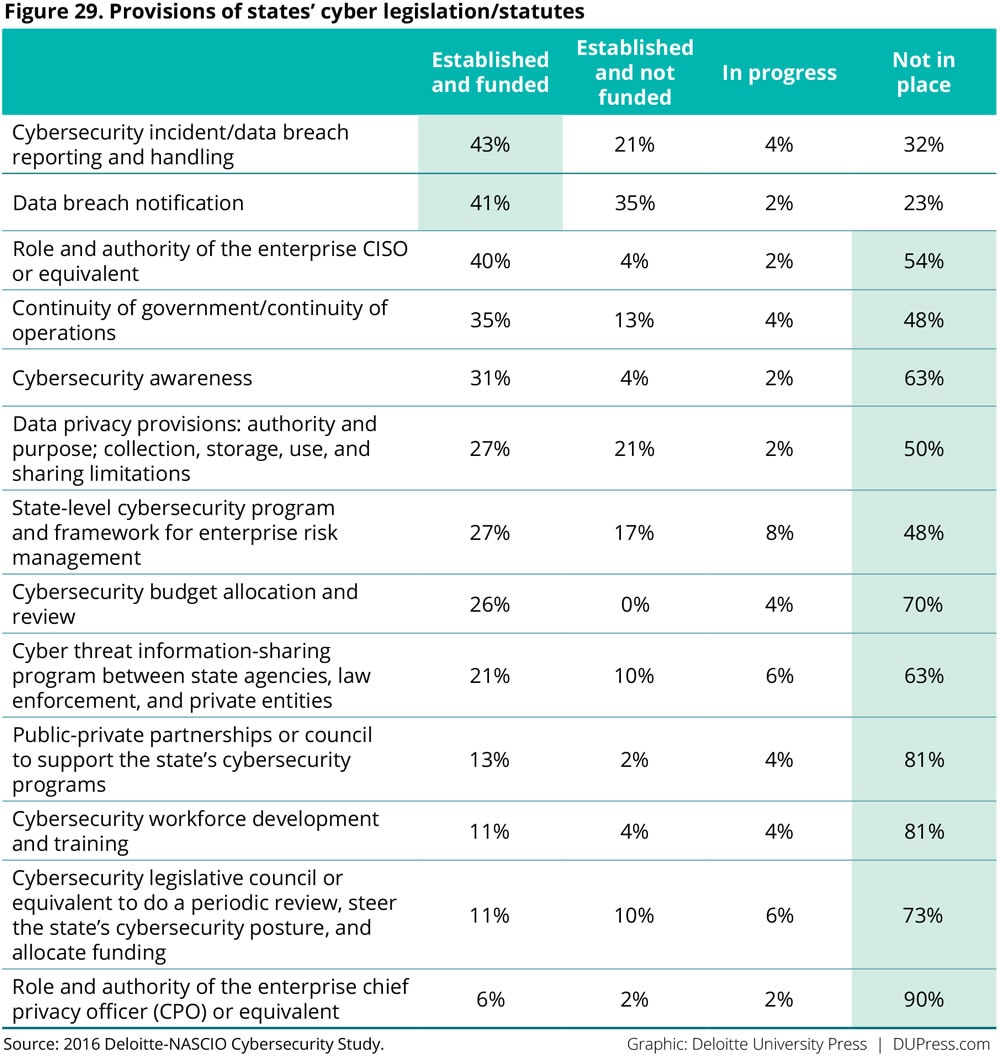

Cyber legislation

Several state legislatures have been active in providing guidance to CISOs regarding implementation of cybersecurity measures—particularly in the areas of data breach reporting and notification. However, most states do not have established cybersecurity legislation in place (figure 29). More than a quarter (29 percent) of states have reported an increase in funding from legislation and grant sources.

Moving forward

In the past two years, CISOs have moved their states forward in the fight against cyber risk. But the threat environment is so complex and evolving that many challenges remain. States faced with a myriad of priorities and ongoing resource constraints may be hard-pressed to allocate sufficient funding to cybersecurity initiatives. Competition for top talent can make it difficult to attract the professionals needed to effectively combat constantly evolving threats.

But CISOs do have one thing in their favor: State executives, including governors, are starting to pay more attention to the issue of cybersecurity. Those who are able to harness this attention have an opportunity to garner more resources and support for their initiatives. In order to make further progress, CISOs should think about the following:

- Strategy: Document and formalize the cybersecurity strategy. Going through the process of socializing the strategy with a broad range of stakeholders has a number of benefits. It ensures input from each of these parties, improving the overall strategy as a result. It strengthens collaborative relationships with other state agencies and departments. It raises awareness of cybersecurity issues. And finally, as our results have shown, it increases the chances of garnering more funding.

- Funding: Work with stakeholders to make cybersecurity a significant line item on state IT and business initiative budgets. For most states, cybersecurity is less than 2 percent of the overall IT budget. Cybersecurity is a business risk to state government, and funding should be commensurate with the risk.

- Communications: Use metrics and numbers to tell a compelling story about cyber risk. The fact that state officials are significantly more confident than CISOs about their states’ ability to protect against cyber risk indicates that the right message still may not be getting across. State officials’ lack of insight into the true business risks of cyberthreats could even affect funding. It is important for CISOs to step up the frequency of their communications—especially with agency business executives and legislators—and to communicate the risks more effectively.

- Talent: Promote the right benefits, modernize your workplace culture, and better define required skills to attract the right talent. The nature of what states have to offer workers has changed—which can be an advantage if positioned correctly. Millennials are not necessarily attracted by the promise of a secure retirement—something fewer states today are able to offer. Many of them find the prospect of “giving back” to be a more compelling reason to gravitate toward an employer. This, along with a rich training and development program, can serve as the basis for a campaign to recruit Millennial talent.

States should consider these components as they better define their strategy and look to create a higher level of awareness. These approaches can help CISOs continue their progress in combating cyber risks.

Appendix: Survey methodology

The 2016 Deloitte-NASCIO cybersecurity study uses survey responses from:

The 2016 Deloitte-NASCIO cybersecurity study uses survey responses from:

- US state enterprise-level CISOs, with additional input from state agency CISOs and security staff members

- US state (business) officials, using a survey designed to help characterize how the state government enterprise views, formulates, implements, and maintains its security programs

CISO profile

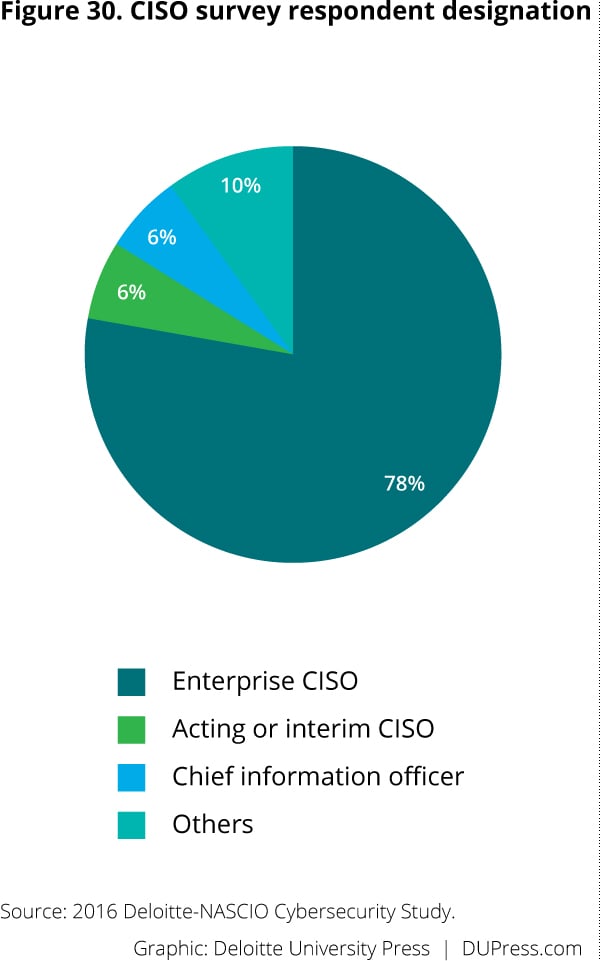

CISO participants answered 59 questions designed to characterize the enterprise-level strategy, governance, and operation of security programs. Participation was high: Responses were received from 49 states and territories. Figures 30–32 illustrate the CISO participants’ demographic profile.

CISO participants answered 59 questions designed to characterize the enterprise-level strategy, governance, and operation of security programs. Participation was high: Responses were received from 49 states and territories. Figures 30–32 illustrate the CISO participants’ demographic profile.

State official profile

Ninety-six state business and elected officials answered 15 questions, providing valuable insight into state business stakeholder perspectives. The participant affiliations included the following associations:

- National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO)

- National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers, and Treasurers (NASACT)

- National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG)

- National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS)

- National Association of State Personnel Executives (NASPE)

- National Association of State Chief Administrators (NASCA)

- National Association of State Procurement Officials (NASPO)

- National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD)

- National Emergency Management Association (NEMA)

- Federation of Tax Administrators (FTA)

- Governors Homeland Security Advisors Council (GHSAC)

- International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP)—Division of State and Provincial Police (S&P)

The two surveys provided an opportunity for survey respondents to add additional comments when they wanted to further explain “N/A” or “other” responses. A number of participants provided such comments, offering further insight into the analysis.

How Deloitte and NASCIO designed, implemented, and evaluated the survey

Deloitte and NASCIO collaborated to produce the 2016 Deloitte-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study. Working with NASCIO and several senior state government security leaders, Deloitte developed a questionnaire to probe key aspects of information security within state government. A CISO survey review team, consisting of the members of the NASCIO Cybersecurity Committee, evaluated the survey questions and assisted in further refining the survey questions.

In most cases, respondents completed the surveys using a secure online tool. Respondents were asked to answer questions to the best of their knowledge and had the option to skip a question if they did not feel comfortable answering it. Each participant’s response is confidential, and any identifying information was deleted after the preparation of the survey reports.

The data collection and analysis was conducted by DeloitteDEX, Deloitte’s proprietary survey and benchmarking service. Results of the survey have been analyzed according to industry-leading practices and reviewed by senior members of Deloitte’s Cyber Risk Services practice, the Deloitte Center for Government Insights, and Deloitte’s Technology and Human Capital practices. In some cases, in order to identify trends or unique themes, data were also compared to prior surveys and additional research. Results on some charts may not total 100 percent based on answer choices such as “not applicable,” “do not know,” or “other.”

Due to the volume of questions, and for better readability, this document reports only the data points deemed to be most important at the aggregate level. A companion report, including all questions and benchmarked responses, has been provided individually to the state CISO survey respondents.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.