Reducing recidivism An ecosystem approach for successful reentry

15 minute read

18 December 2018

Emily Livingston United States

Emily Livingston United States Nell Todd United States

Nell Todd United States Andrew Forth United States

Andrew Forth United States Bruce Chew United States

Bruce Chew United States

As individuals reenter society, numerous challenges threaten a return to prison. In order to lower recidivism, agencies should work to tackle issues related to probation requirements, job opportunities, housing, and behavioral health services.

The United States has struggled for years to provide effective support for the more than 650,000 individuals returning to society from prison every year.1 Over 75 percent of those leaving prison are back behind bars within five years.2 A recent study estimates that the cost of incarceration is US$1 trillion annually, taking into account the foregone wages and debt accumulated by those behind bars, as well as increased rates of homelessness among the family members of those who are locked up.3 For every dollar in corrections costs, incarceration generates an additional 10 dollars in social costs. 4 Therefore, reducing recidivism is a widely recognized imperative, whether due to humanitarian or hard dollar costs.

The problem, however, does not have an easy solution. On the surface, it might seem successful reentry simply requires that the person walk a straight and narrow path. But the intractable problem of recidivism is often more complicated and may be better understood by examining the complex challenges many individuals face on their journey to reenter society.

A reentry journey

Learn More

Read more from the Government and public services collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

As incarcerated individuals prepare to reenter their communities, there are many factors that determine whether they will build successful lives postincarceration or end up back behind bars. The potential challenges to successful reentry include complying with probation requirements, finding a job, securing housing, and, for many, accessing behavioral health services. To better understand these challenges, it can be useful to examine reentry from the perspective of an incarcerated individual.

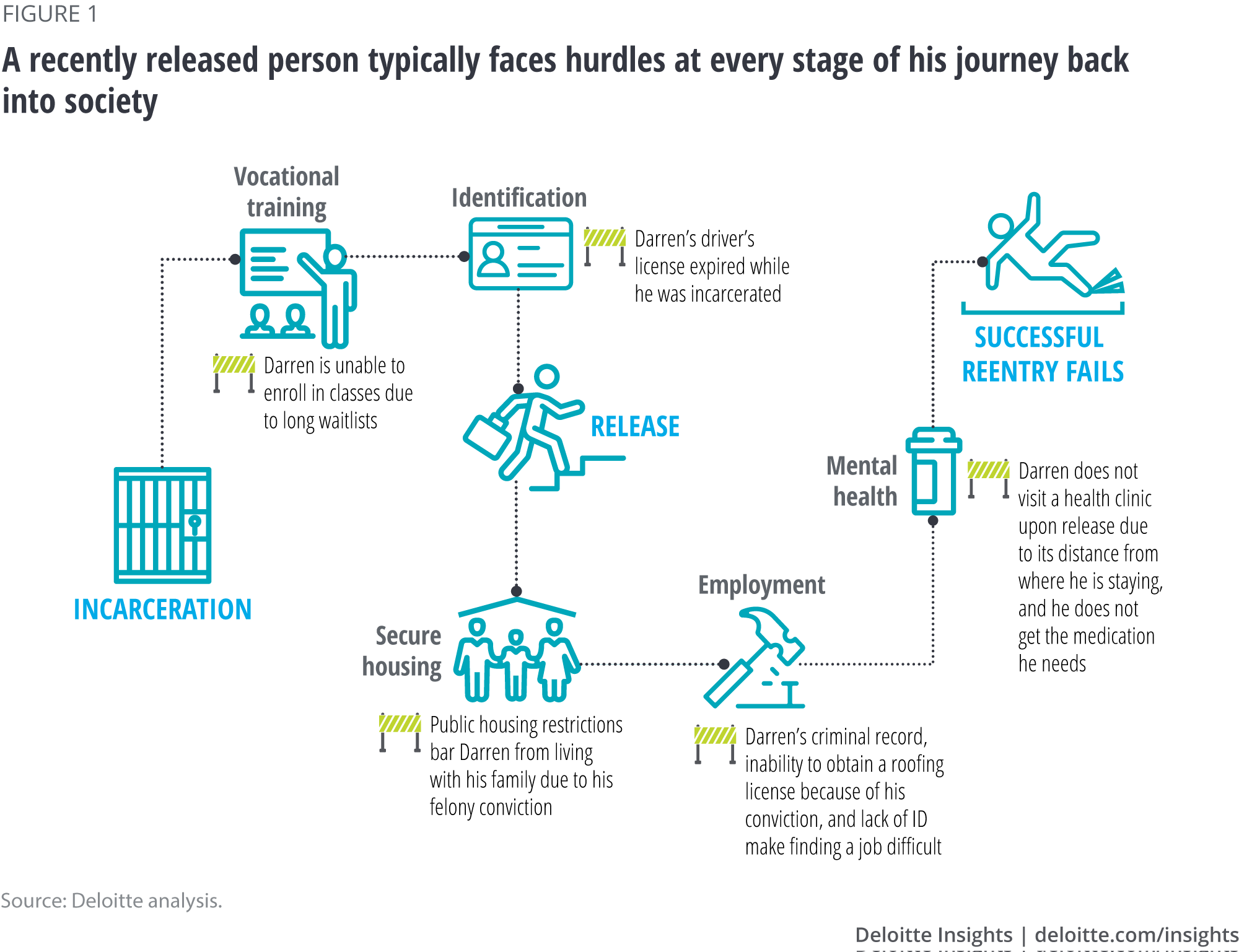

Consider Darren, a 25-year-old man who pled guilty to felony distribution of cocaine, served five years, and was just released, but remains on probation for five years. While he was in jail, Darren completed his GED, or high school diploma, and tried to enroll in the two vocational training programs offered, but he never got off the long waiting lists that commonly exist for such programs. Once released, he stays with his mom and two brothers in their federally subsidized two-bedroom apartment while he tries to get back on his feet.

Darren worked for a construction company before he went to prison and specialized in roof repairs, though he never obtained his roofing license. He applies for a roofing license once released, knowing this would make him more marketable, but he is surprised to learn his state will not issue him a license due to his felony conviction.

Darren applies for several jobs in other industries, but applications always ask about a criminal history, which makes it difficult for him to get an interview. When he finally does get an interview, he must explain to potential employers that he would need to leave early twice a week—once to meet his probation officer and once to take a court-ordered urine test. He is offered a minimum wage job delivering groceries, but his driver’s license expired while he was locked up, and he has not been able to renew it yet. Having a license is a condition of the job, so Darren cannot accept the offer.

When his family’s landlord finds out that a convicted felon is staying in the apartment, he informs Darren’s mother that the entire family will be evicted unless Darren leaves. Darren considers staying with a friend but knows that his old friends are not good influences and would likely put him at risk for reoffending. Darren has no choice but to pack his things and move to a men’s shelter, where he plans to stay just for a few days. He applies for other apartments, but without a valid ID or enough money for first and last month’s rent and a security deposit, he is unable to get his own place.

Two weeks later, Darren is still in the shelter, and his bag is stolen while he sleeps, which contained some cash his mother had given him and the 30-day supply of medication for his depression that his doctor gave him before he left prison. He has a referral for a community health center but has not been there yet, mostly because it is an hour-long bus ride to get there. The loss of his medication represents a major setback for Darren, especially because the shelter is rife with drug use and crime. With no housing, no job, and no medication, Darren’s plans for a new life seem impossible to attain (figure 1). Seeing no other options, he decides to reconnect with some of his old friends after all. Darren is at serious risk of reoffending and ending up back in jail.

Using an integrated ecosystem perspective to overcome challenges

No one set out to make Darren’s journey difficult, but the diverse set of organizations involved has ended up doing just that, with each focused only on its own narrow piece of the world. Darren, who must navigate interactions with all these parties to be successful, is not well prepared to take this task on alone. In the private sector, many businesses already think about their business and their customers not just in terms of providers and consumers but also as part of an interconnected network. These networks—or ecosystems—typically bring together multiple players of different types and sizes to create, scale, and serve markets in ways that are beyond the capacity of any single organization. Their diversity and their collective ability to integrate, learn, adapt, and innovate together are key determinants of their longer-term success.5

The same thinking can be used for public policy challenges such as failed reentry programming. This view moves us beyond just examining reentry policies to exploring reentry’s role within the ecosystem of agencies, businesses, and society as a whole. This integrative perspective explores how components relevant to the reentry ecosystem play a role in creating barriers or fostering success.

Seen through this lens, Darren’s journey highlights five ecosystem components that can have a significant impact on recidivism.

Education and vocational training: The provision of education and vocational training during incarceration has consistently reduced recidivism rates. A recent RAND report found that the odds of recidivating are 43 percent lower for people who participate in educational programming than for those who do not. That same study found that participating in vocational training decreased the likelihood of recidivism by 36 percent.6

Although most prison systems offer some form of educational programming and vocational training, participation rates have declined over time.7 However, this is likely because as prison populations have grown, investment in postsecondary educational and vocational programming has not kept pace, and a smaller proportion of prisoners are able to participate.8 Just as Darren was unable to get off the waitlist for two vocational programs, many prisoners who want to participate are also unable to do so. This was a serious opportunity missed, and one that could have been the difference between success and failure for Darren.

Employment: Finding a job is often a crucial component of successful reentry, and those who are employed have been significantly less likely to reoffend.9 Not only does employment enable returning offenders to meet basic financial needs, but it can also provide a sense of dignity and self-worth that is key to becoming a stable, law-abiding citizen. However, securing a job often proves to be especially difficult for former offenders for several reasons. Employers are often wary of hiring those with a criminal record, and many states bar the issuance of certain professional licenses to those with felony convictions.10 Those just coming out of prison may also lack proper identification to prove employment eligibility.11 We saw a number of these factors impacting Darren’s job search: He was denied a roofing license because of his conviction, which limited him from entering a field where he had job experience; answering questions about his criminal history on a job application prevented him from even being interviewed by many prospective employers; and his lack of a current driver’s license forced him to decline a job for which he was otherwise qualified.

Criminal justice system compliance: Conditions of probation or parole are intended to make success more likely, but they may have unintended effects on other parts of the ecosystem by stressing monitoring, potentially at the expense of ease of reentry. Specifically, some conditions can hinder employment prospects. For example, sentencing judges often require those with drug offenses to have regular tests and check-ins with their parole officer during what could be working hours. Balancing all of these obligations in addition to the transition into society can be challenging.12 Darren’s probation obligations made the logistics of working a full-time job during normal business hours extremely difficult. In addition to asking employers to overlook his criminal history, he was also forced to ask for special accommodations once employed. Given these limitations, it is not surprising that most employers were unwilling to hire him.

Housing: Housing is another critical component of the ecosystem for those reentering society; those who do not have stable housing are more likely to recidivate.13 Many citizens returning from prison cannot afford to pay market price for a place to live, while federal law grants public housing authorities broad discretion in denying benefits to those with criminal histories.14 Even if tenants have not engaged in criminal behavior, the Public Housing Agency can evict them for the conduct of anyone in their household.15 These broad restrictions put Darren’s family in a terrible position; they had to choose between supporting him in his transition and losing their subsidized housing. Darren’s inability to stay with his family meant he stayed in a shelter, and when that proved unsafe, he reconnected with old friends who were a bad influence.

Behavioral health care: Finally, behavioral health care is another important component for the majority of those returning from prison. According to a study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 56 percent of state prisoners, 45 percent of federal prisoners, and 64 percent of those in local jails have a diagnosed mental health issue.16 Adults with mental illness are likely to recidivate more quickly and at higher rates than those who do not have a mental illness.17 It is critical that former offenders maintain continuity in their treatment when they return home, including treatment for substance abuse disorders. Darren’s inability to connect with a community health center due to the distance and cost of travel proved to be an impediment in his recovery and exacerbated the other challenges he was already facing.

Each of these ecosystem components—educational and vocational training, employment, criminal justice system compliance, housing, and behavioral health care—have room for improvement on their own, and much has been written on this. However, the ecosystem perspective brings additional insight by examining them as an integrated set and understanding their interactions. This allows for unintended consequences to be identified and potentially addressed—the effect of probation requirements on employment opportunities noted above is a prime example (and is examined further below). The ecosystem perspective also highlights integrative elements whose importance may be underestimated otherwise, such as the lack of a simple driver’s license.

Consider the difficulties Darren encountered simply because his driver’s license expired while he was incarcerated; it became more difficult to find a job and a place to live. This is a common barrier for returning individuals, and its impact may be best understood by looking across the various components of the reentry ecosystem. The opportunity to remove this challenge also potentially involves participants from across the ecosystem.

Many state agencies require identification to access services. For example, to apply for Medicaid, most states require a current photo identification and a birth certificate.18 However, only one-third of state prisons ensure that individuals leave prison with a state-issued identification.19 According to a 2016 Deloitte report, approximately 58 percent of individuals enter federal halfway houses without identification20—effectively barring them from driving a car, opening a bank account, leasing an apartment, or verifying their identity for prospective employers. It can take weeks or months to get a new ID postrelease—for instance, parolees in California wait an estimated two to six months to receive an identification card from the Department of Motor Vehicles.21

How can taking an ecosystem perspective help tackle the identification issue? From arrest to reentry, there are opportunities to ensure that individuals maintain or obtain identification that “follows” an individual throughout the criminal justice ecosystem. What if …

At arrest, the apprehending law enforcement officer checks to see if an individual has an ID. If an individual does not have an ID, the pretrial services officer provides support for getting an ID and documents their progress in the sentencing report that is prepared for the court. During incarceration, the Department of Corrections then takes the responsibility to ensure that IDs follow the incarcerated throughout their sentences and checks on expiration dates for IDs, helping those with expiring IDs obtain relevant paperwork (e.g., birth certificate) prior to release. The prison would invite representatives from the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) or other state administrative agencies into the jails when necessary to facilitate the acquisition or renewal of IDs. Rates of prisoners leaving with current IDs would be tracked, and there could be financial incentives (determined by local, state, or federal lawmakers) for correctional facilities to comply. Halfway houses and parole officers then provide final support to ensure the released individual retrieves his/her ID as quickly as possible. Joining in advocacy efforts and potentially participating in process activities (e.g., travel) may be reform-oriented nonprofits or religious groups whose ministries based in forgiveness, redemption, and the importance of second chances make them natural partners in promoting successful reentry. Support might also be found from other nonprofits focused on victims’ rights and public safety, and law enforcement agencies that understand that successful reentry efforts lead to reduced victimization and safer communities and potentially frees up money that would otherwise be spent on prison costs. These funds could potentially be redirected toward supporting these organizations’ efforts by increasing law enforcement resources, or to nonprofits through grants.

Getting Darren and others like him an ID requires a governance structure that appreciates and incentivizes disparate units of the criminal justice system and beyond. The structure strives to create an environment in which documents do not slip through the cracks and information is handed off seamlessly across the ecosystem. But because organizations within ecosystems often lack central coordination and aligned goals, fixing the current system likely means providing targeted incentives and nudges to help critical actors play a proactive role in reducing recidivism. In Darren’s case, providing incentives for the DMV to send incarcerated individuals new IDs just prior to release—even without a well-coordinated interagency effort—would have substantially improved his transition.

This approach to solving the ecosystem challenge looks for high-leverage/low-cost intervention points in an individual’s journey to reintegration into society. These types of concrete ideas have been considered by the Department of Justice (as described in a 2016 memo22) but are also applicable at the state and local level. Recently, the White House highlighted the employment component of the ecosystem, announcing a program to help Americans who are reentering society from prison to find jobs. The Department of Labor recently released US$84.4 million in grants to community groups, states, and localities to advance programs aimed at reducing crime and filling open jobs.23

Applying technology to old activities and solutions

The ecosystem perspective seeks to integrate the roles of the diverse participants and fragmented perspectives associated with an individual’s reentry. In many ecosystems, that same fragmentation often leads to underinvestment in technology, as limited lines of sight may contribute to a mismatch between perceiving and capturing costs and potential benefits. Add to this the rising volume of incarcerated people that has taxed the ability to keep up with demand, and it is no surprise that there are untapped opportunities to take advantage of new technologies.

Ecosystem solutions can be supported through existing and emerging technology. One initiative that incorporates new technology solutions is the US$100 million Safety and Justice Challenge, led by the John D and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to reduce over-incarceration and address justice disparities through innovative criminal justice reforms.24 The city of San Francisco is developing a Web-based recidivism analysis dashboard, integrating data from multiple justice agencies to support the development of data-driven sentencing and supervision policies.25 The tool is intended to provide real-time data to inform resourcing decisions on supervision and programming as well as tracking and communicating progress on reducing recidivism.26

It is relatively straightforward to imagine other technology applications that would affect reentry. Cloud-based systems make it easier to share information and documents across stakeholders, including risks and associated needs. Web-based applications allow for automatic updates about employment opportunities and skills training. Augmented and virtual reality could be used to prepare incarcerated individuals for reentry through simulations of work or life situations, e.g., self-checkout, using a laundromat, looking at a subway map, and buying a subway ticket. Video conferencing and messaging tools for seamless communication could be used for check-ins with a probation officer, including check-ins after normal business hours that would minimize conflicts between probation obligations and work obligations.

For Darren, this would have meant that assessments and other information would follow him from arrest to release, saving his case managers time and Darren frustration. He would have had access to virtual training, especially useful while he was still on the waitlist. By practicing daily tasks that had become unfamiliar, he would have felt more prepared to reenter society. He would have been able to talk with his case manager, even if he didn’t have a car and driver’s license or the money for bus fare.

The case manager’s role is worth further consideration. Technology does not just allow the automation of existing tasks; it allows for the rethinking of roles entirely. Though a keyboard has replaced the typewriter, the activities and tasks of Darren’s case manager would look familiar to a case manager from 40 years ago. But new, smarter technologies can redefine the case manager’s role in significant ways. Predictive analytics, behavioral economics, the gamification of incentives, mobile communications, geospatial monitoring, machine learning, and other new and emerging technologies all have the potential to transform reentry compliance and interactions.27 In-person, calendar-driven check-ins could give way to analytics-driven ongoing monitoring of behaviors and risks that trigger real-time electronic outreach.

A future case manager might, for example, provide Darren with the exact information needed to refill his prescription, while a supporting system alerts them both via text when it is time to do so. This could have helped Darren respond to the loss of his medication, instead of leaving him alone to solve the problem. Using geospatial monitoring, Darren could check in when he arrives at the pharmacy, allowing his case manager to follow his progress. And gamifying good behavior, such as refilling his prescription on time, attending vocational training, and checking in at registered nonprofits and support groups, could increase Darren’s incentives as well. The case manager could be both monitor and enabler for a virtual hub of training, job opportunities, risk assessment, and communication. In government, this type of technology-augmented workforce of the future appears closer than one might think.28

The case manager’s agency can reinvent the role alone, but it can be far more impactful if it considers the broader ecosystem of actors. Coordinating with others, whether horizontally or led by state executives, can unleash even greater opportunities for leveraging data across the justice and reentry processes. Unfortunately, current insular and inconsistent data system designs can make this difficult. A more collaborative and consistent data management approach could create a platform for advanced analytics to better align needs to resources and actions today and, through probabilistic prediction, tomorrow as well.

Disrupting the existing systems

Technology today is not just transforming the nature of work; it is transforming entire industries. The rapid evolution of digital technology capabilities has enabled players such as Amazon, Uber, and Airbnb to disrupt traditional industries and the way they go about their business. While this may be threatening to a commercial incumbent, it can be enticing to those faced with an intractable problem like recidivism. If the existing structure can’t be solved, the thinking might go, perhaps we can transform it into something more amenable to a solution.

Just such an opportunity may exist in assisting incarcerated individuals toward more effective reentry. Incorporating new technologies and designing more interconnected systems may require significant investments of time and resources but can lead to significant improvements in outcomes. Perhaps the most impactful way to address the problem is to bypass the problem of reentry for candidates who are not deemed public safety threats by not removing them entirely from society in the first place. This would not only help their reentry problem but could also free up resources for the rest of the population. The government spent over $150,000 to imprison Darren. But what if they had instead placed Darren on probation and required him to wear a global positioning system (GPS) location-tracking device that would have allowed law enforcement to limit his movement to home, work, school, or even drug counseling?29

A 2012 study in Washington, DC, found that electronic monitoring helped save costs of nearly US$600 per offender for local agencies, reduced recidivism by 24 percent, and gave a net benefit to society of US$4,800 per person across the criminal justice system.30 Aside from fiscal savings, electronic tracking may actually be more effective than physical imprisonment in helping offenders become productive citizens. One study noted the failure rate of offenders reduced by 31 percent in one state.31 New data analytic tools can be used to identify offenders who are the best candidates for electronic monitoring and those in the program who are in the most danger of violation.32

Imagine a world in which Darren had bypassed time in jail. Darren might have been able to keep his job, allowing him to afford a place of his own and avoid the instability of homelessness. A felony record might still have impacted his ability to get a new job or qualify for public housing, but the disruption of being entirely removed from his life and the subsequent challenges of reentry could have been avoided. Most importantly, Darren might have been able to maintain the support systems he would need to avoid reoffending. However, if Darren were required to shoulder the cost of the electronic monitoring, as happens in many jurisdictions, that financial burden could actually undermine efforts to ensure he is successful in his reintegration into the community after his sentence.

Electronic monitoring is a possible solution that is still evolving. The related technologies continue to advance, and states now use electronic monitoring in a wide variety of settings, such as a pretrial supervision alternative to jail.33 With the number of GPS-monitored offenders now in the tens of thousands,34 this is an area of active study. But it is worth discussing potential privacy and ethical concerns, and potential bias associated with predictive analysis or other ways of determining who might be eligible for electronic monitoring. Ultimately, the potential gains of alternatives to physical incarceration for government, society, and individuals are too great to ignore.35

Getting traction on an intractable problem

Recidivism has resisted the traditional deconstructive approach that government and other large enterprises have traditionally deployed: assign pieces of the whole to different organizations, and task them with improving their individual processes in the hope of better overall outcomes. Recidivism has proved intractable to this approach because it is caused by a variety of factors, may require proactive collaboration among many different stakeholders, and has no one right answer.

But we have seen progress in attacking intractable problems when the pursuit of solutions is reframed from a piecemeal approach to an integrative, ecosystem-based approach that involves a broader set of participants leveraging new technologies and new, potentially disruptive ways of attacking the problem.

Reducing recidivism is achievable, but it will likely require reducing barriers to areas such as training, employment, behavioral health, and housing, for our returning citizens. Ecosystem- and technology-based solutions can work, and are potentially reinforcing rather than mutually exclusive. Broadly and successfully applying these approaches could be impactful, but it will not be easy. The disruption of old models is, well, disruptive. But every citizen who is released from prison should be given the chance to reenter society, not simply because it saves our government money but also because of the human costs of failure. Out of respect for the dignity of those who are trying to rebuild their lives and for all the family members who are affected, we should do more. Darren’s story is a tragic one, but it is an avoidable one as well, if we are all willing to think creatively and invest in the success of people like him.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.