The new digital divide has been saved

The new digital divide The future of digital influence in retail

12 September 2016

Today, retailers almost universally recognize that digital has reshaped customer behavior and shopping forever. So why are so many traditional brick-and-mortar retailers still so far behind at creating the digital experiences that customers really want?

Foreword

This, the 2016 version of Deloitte’s New digital divide report, deepens our exploration of the growing gap between the digital experiences that brick-and-mortar retailers are delivering and the experiences that their customers actually want. It continues the work we have been doing since 2012 to track the impact of digital on consumers’ behavior and their shopping habits.

When we started writing the New digital divide and talking about digital influence, many challenged (and some laughed at) our belief that digital was changing the in-store shopping experience in ways that were not fully understood. But surprisingly quickly, those challenges were drowned out by a chorus of believers, and today there is almost universal recognition among retailers that digital has reshaped customer behavior and shopping forever. In fact, a quick listen to any earnings call will validate that retailers’ investments mirror that recognition and commitment to change.

So then why are so many traditional brick-and-mortar retailers still so far behind at creating the digital experiences that customers really want?

Simply put, it is because these retailers have focused excessively outward—looking primarily at their e-commerce competitors—while building their digital businesses in an attempt to anticipate customers’ needs and preferences, at the expense of paying closer attention to the cues their customers were giving them about what they really want. Add to this a multitude of distractions around hot topics such as big data, beacons, and virtual reality, and it is no surprise that many retailers over the last few years have sought to read the future through a telescope—putting an unhealthy focus on competitors—at the expense of listening to their own customers. This has only led to the digital divide getting wider.

The primary goal of this work has always been to help retailers refocus and close this gap. To that end, in this edition of the New digital divide, in addition to drawing on our research and client work, we’ve included a series of customer insights made possible by the Deloitte Retail Volatility Index, our proprietary measure of the forces driving shifts in market share across retailers.

All of our work suggests that many of the digital answers retailers have been seeking externally may, viewed properly, live within the walls of their own stores. Indeed, perhaps the most important thing we’ve learned over the last year is that the most accurate picture of the digital future at any retailer will perhaps be best viewed through a microscope, not a telescope—by looking carefully at what is close at hand to inform better decisions around influencing customer behavior rather than focusing on competitors.

Jeff, Lokesh, and Kasey

Digital influence and retail volatility

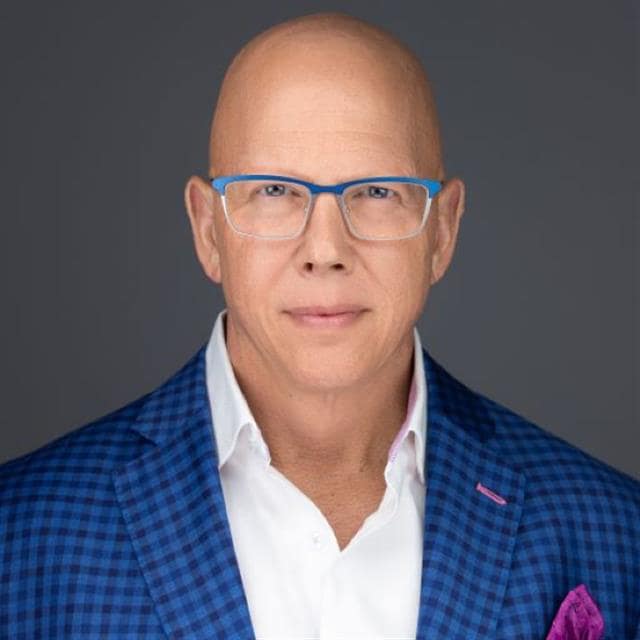

In 2016, digital influence continued its rapid growth, albeit at a slower rate than we’ve historically seen (figure 1). Today, $0.56 of every dollar spent in a store is influenced by a digital interaction. And when we include the primary source of growth in retail—online sales—the impact of digital influence is even greater (figure 2).

But even as digital influence has risen, retailers’ ability to influence the purchase journey has decreased. Why? Because the large e-commerce players, as well as digital platforms such as Pinterest, are operating at such scale now that they are shaping customers’ definitions of what a great customer experience is. Not only that, but they are also simply more connected (often in real time) to the customer’s needs than the typical brick-and-mortar retailer.

How did this happen? Think for a second about the fallacy that any single retailer, which only interacts with a customer six to eight times per year (in a mostly transactional manner), can gather enough information to provide a meaningfully personalized experience. Contrast this with the kind of relationship, trust, and understanding of preferences and purchase intent that a digital platform like Pinterest can create when they interact with that same customer for several hours a day.

As a result, almost universally, customers’ preferred method of locating, buying, and receiving products in-store has been redefined by their online experiences.

In addition, customers today can go to their Internet browser, have it search the broad, fragmented marketplace, and get exactly what they want. No longer do they have to settle for something that is close to what they want; the browser curates the exact assortment they are seeking, far more quickly and easily than a visit to the mall. This dynamic has led to a significant increase in the shift of market share as nimble small and mid-level players collectively steal share from larger, more traditional, at-scale retailers. This fragmentation and volatility in the market is reflected in Deloitte’s Retail Volatility Index (figure 3).1 The competition is no longer coming from the big box across the street, but rather from a myriad of newer, smaller competitors, most perhaps too small to capture the attention of the big players, but each eating away at market share.

As share shifts, the single biggest challenge many retailers are facing is the cultural gravity of their own traditional functional processes, talent practices, and business models (in functions including merchandising, marketing, and supply chain). The pull of these traditional structures is so great that these retailers, should they remain overly outwardly focused on their competitors’ practices, are destined to remain 12–24 months behind in recognizing and meeting their customers’ changing needs. For example, many retailers are still utilizing the same traditional key performance indicators that have been used for years rather than evolving how they define success to keep up with changing customer desires. Several examples:

- Retailers have been painfully slow at moving from a legacy “campaign” mind-set (where everything is planned around sales events) to a “customer” mind-set (where the planning process is built around the needs of different segments of customers instead of sales events).

- We regularly see historical attribution models that do not properly recognize customer interactions across channels or ascribe the proper importance to different interactions along the customer journey (that is, helping customers easily select and validate products may just be the most important customer interaction on the path to purchase).

- Adding to this confusion, the traditional approach to measuring cross-device usage frequently overstates key metrics such as audience size and engagement—introducing even more “noise” into many of the budgeting and planning processes.

- The staffing and talent models in key business functions such as social media, media planning, and customer relationship management (CRM) do not recognize how these business functions have changed with the advent of the large digital platforms. Long-standing disciplines such as buying media have completely changed in today’s environment and require very different skill sets than these functions did even 12 months ago.

Reliance on these traditional approaches leads to flawed budgeting and decisions. Retailers need to not only understand these changing needs better and work toward breaking free of outmoded ways of operating, but also completely revisit the historical data they have, build partnerships for data they wish they had, and find ways to generate data they never knew they needed.

The takeaway? Don’t try to build everything yourself! Retailers should embrace the native capabilities of their digital touchpoints and integrate with platforms where their customers are already interacting at scale rather than trying to build such platforms themselves.

Moreover, thriving in disruption requires taking a new look at one’s own financial structure, organizational structure, and ecosystems to drive the agility needed to respond to and anticipate the needs of today’s digitally connected consumer. Where to start? Consider resetting legacy planning and budgeting functions: Traditional budgeting and return on investment measures simply have not kept pace with shifts in customer behavior. For example, few retailers leverage an integrated budgeting/planning process that plans holistically across channels. This oversight often results in two things: double and triple counting key metrics such as customer interactions, and failing to recognize programs that are decreasing in productivity.

As a result, increasingly, we are seeing senior management express frustration as multiple business units claim individual credit for the same result. To quote a senior executive we spoke with recently, “My sales are flat, but if I added up all of the incremental ‘wins’ each of my functional leaders is reporting, our business would have grown by 20 percent.”

Under the microscope: The path forward

Encouragingly, our work illuminates huge pockets of untapped sources of insight that, perhaps surprisingly, live within most retailers’ own four walls. A focus on where to look and how to better understand this information can significantly accelerate the journey to digital effectiveness, providing competitive advantage and differentiation. Our research suggests that retailers should focus on two primary areas to deepen their understanding: customers and categories.

Customers: The Millennial mind-set

Each year, our digital divide research reveals new and exciting developments about how customer behaviors are changing. This year, our work revealed a rapidly accelerating dynamic in customer behavior that we call the “Millennial mind-set.” In short, we are seeing demographic groups that have displayed historically lower levels of digital influence start to embrace some of the newer digital features and functions available in the market.

That said, there are clear limits as to just how far consumers will go in using digital services when making purchase decisions. For example, while we see older customers adopting the use of mobile devices to locate products, we do not see them fully embrace more sophisticated mobile capabilities such as mobile payment systems. This continuum of adoption and usage suggests that retailers will need to manage a delicate balance of introducing newer functionalities while simultaneously maintaining an acceptable service level with their less digitally sophisticated customer base.

Retailers can help themselves in this effort by understanding the customer journey and the key elements, or “moments,” of that journey that contribute to the overall customer experience (figure 5). According to our analysis, each such moment is potentially subject to digital influence.

Using these moments in the customer journey to guide the analysis, this year’s research found some compelling consumer behaviors at various points in the journey, as well as several changes from last year’s findings:

- Consumers this year report that they desire to search for information about a specific product or product category rather than receive information during the find inspiration moment. They are influenced less by advertising pushed to them in the face of what appears to be a rapidly growing trend for consumers to take their own lead in the shopping journey and pull out what they want (see figure 6). One implication is that, rather than pushing information at consumers through advertising to inspire them in moments defined by the retailer, retailers should instead identify the steps in the shopping journey where the consumer is most likely to be inspired, and then deliver that inspiration through the consumer’s preferred channels of engagement.

- Over 93 percent of consumers report using a digital device in the browse and research moment.

- The purchase and pay moment is critical: When checking out, shoppers consider a quick and easy process two times as important as any other experience.

- The return and service moment appears to be more influenced this year by digital devices than in 2015, with 39 percent of shoppers likely to initiate a product return or refund from a digital device compared to just 20 percent last year.

Even as our analysis reveals ongoing changes in consumer preferences and behaviors at various moments of the shopping journey, we also found that a significant number of consumers want to manage the journey themselves, directing the ways and times in which they engage retailers rather than following a path prescribed by retailers or marketers. Indeed, 66 percent of this year’s consumers cite the desire for a self-directed journey, up from 30 percent just two years ago. Providing further evidence of this phenomenon, when it comes to product awareness, 76 percent of shoppers state that they look at a retailer’s website or app to become aware of a product or category on their own. Further, we saw a marked increase in the willingness to share data, with 48 percent of shoppers and 58 percent of Millennials willing to share data in return for personalized service.

Sixty-six percent of this year’s consumers cite the desire for a self-directed journey, up from 30 percent just two years ago.

Additionally, due to the nature of digital and mobile, the journey has become less linear and more fluid, with the potential for retailers to use digital services to create a “wormhole” from one step in the journey to another. For example, shoppers for women’s apparel often find the find inspiration step critical. Let’s assume that a shopper finds inspiration in this step through social media. Now imagine if the customer were able to make a purchase directly from the inspiration step by buying through social media. The retailer will have captured the consumer at a time when his or her interest is piqued and digital influence is high.

The bottom line is that customers are willing to engage in meaningful ways—it’s just that most retailers are not providing meaningful opportunities for consumers to do so. For example, 3 percent of shoppers used the “buy online pickup in store” (BOPUS) option in their last trip but 13 percent indicated that it is their preferred method of delivery. Retailers need to leverage digital touchpoints at key moments that matter for any given category to propel the consumer toward purchase before they lose motivation. Whether communicating through wearables, in-home technology, in-store beacons, or other methods, a connection with consumers can be made real-time, in both directions, and beyond geographical considerations. This connection is not necessarily governed by time or location, and should support today’s shopper’s natural inclination to champion his or her own shopping journey. The most effective way to capture wandering shoppers is to let them engage and buy anywhere along the journey they choose.

Categories: Understanding the nuances

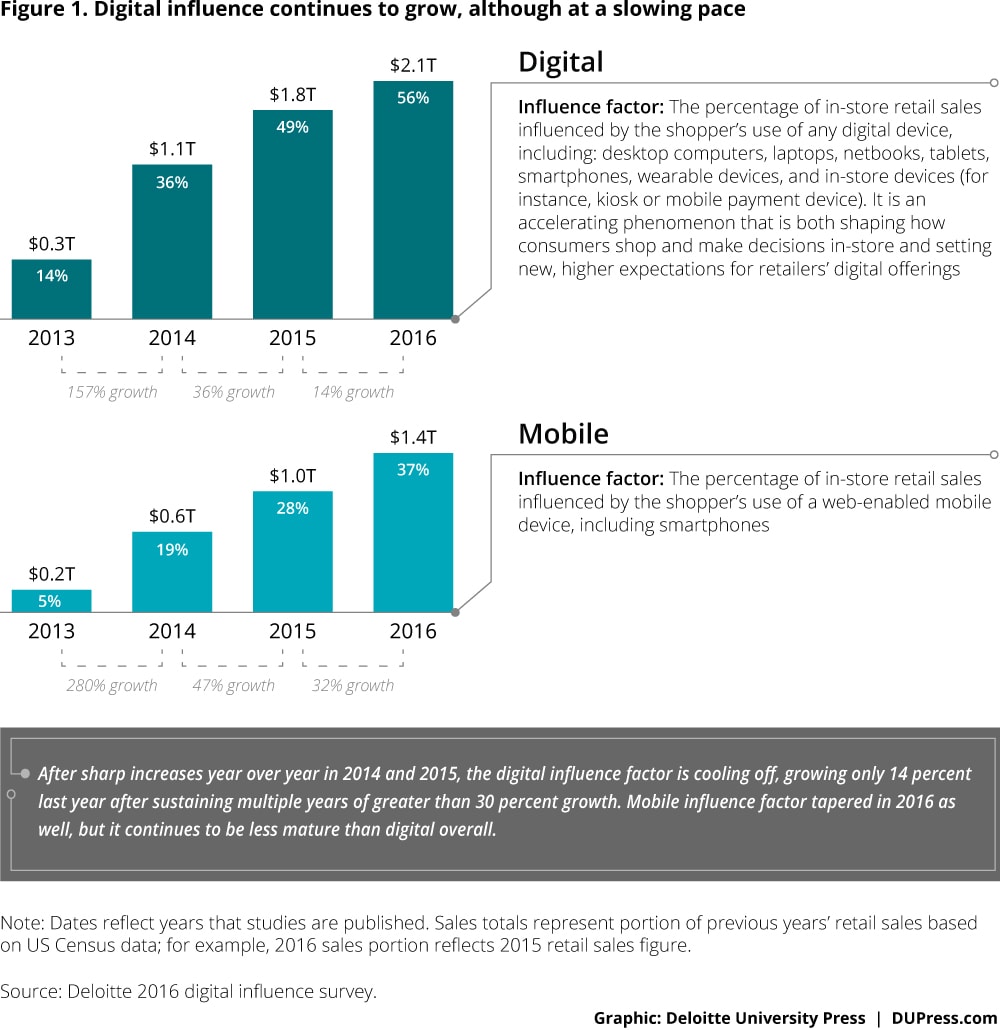

In our 2015 report,2 we discovered significant differences in how digital impacts behaviors across merchandise categories. This year’s research continues to elaborate on those differences. One anomaly is readily apparent: While digital influence growth is slowing overall, it continues to rapidly accelerate in categories such as grocery and health (figure 7).

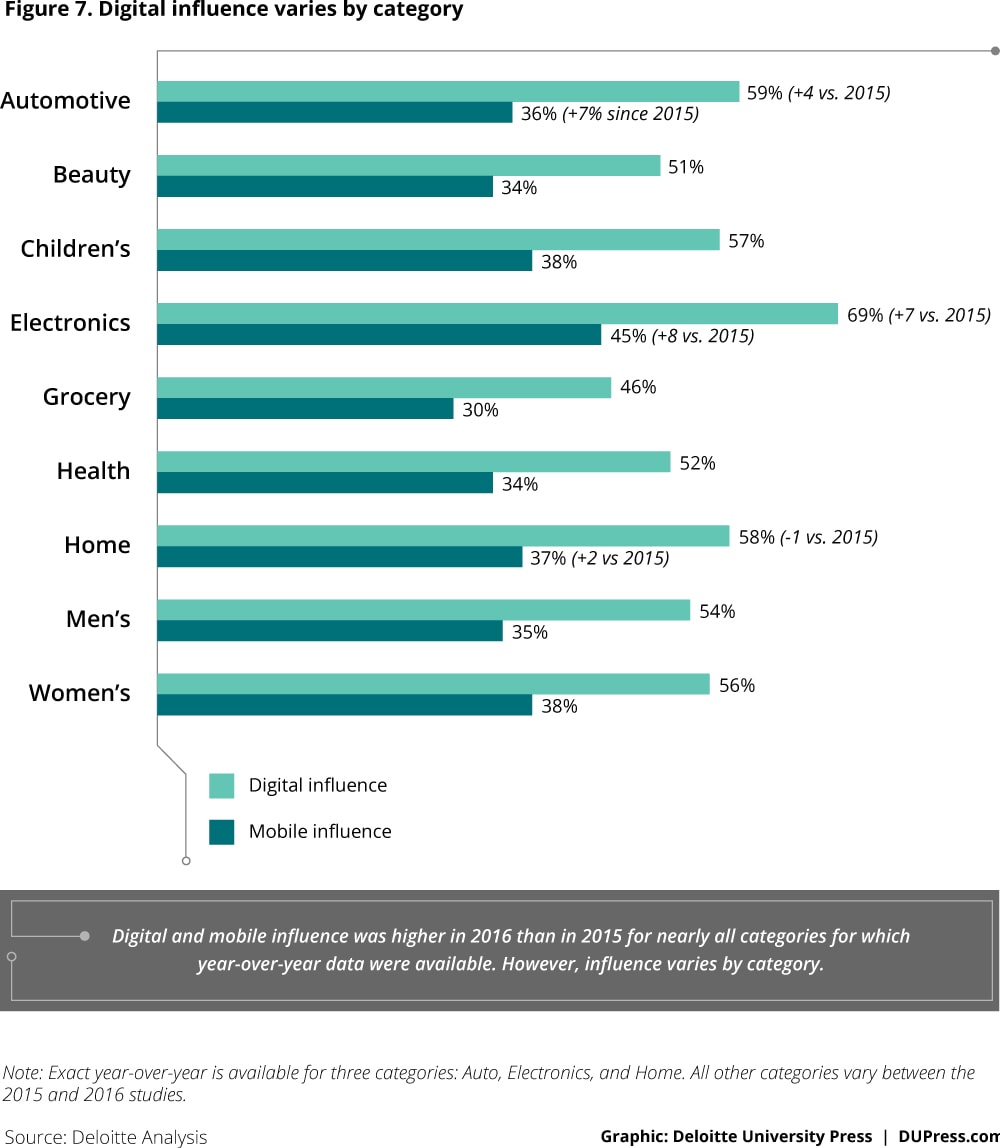

To better understand how different customer behaviors are across categories, consider the example of shipping fees. Almost every retailer has implemented free shipping and is stressing their supply chain in an effort to execute against same- and next-day deliveries. But does every customer really require free shipping, and is same/next-day delivery really a customer imperative across the board? Our research says no, and, in fact, it appears that Amazon has redefined the acceptable window for the receipt of merchandise (figure 8).

At face value, across all categories, only 35 percent of customers exhibit a willingness to pay for shipping on online orders—hence all of the energy (and margin erosion) around providing free shipping. But, when preferences are examined at the category level, it quickly becomes apparent that almost half of those shopping in the children’s (47 percent) category are willing to pay for shipping. Given the highly “giftable” nature of these categories, which creates an artificial timing, and the fact that parents of young children are arguably among the most demanding, time-starved shoppers, we believe that by chasing free shipping universally, brick-and-mortar retailers are missing a significant opportunity to establish competitive advantage (through availability) and profitability (margin).

In addition, we are anxiously awaiting the day when some retailer aggressively challenges the notion that shipping online purchases is really free. The last time we checked, most “free shipping” services required some type of paid membership . . . meaning it really isn’t free!

Conclusion

Despite the challenges we’ve outlined, we’ve never been more optimistic about the opportunities that exist for traditional brick-and-mortar retailers to regain their footing in the digital marketplace. Among the almost infinite list of options, there exist several common themes for successfully navigating the road ahead:

- Don’t try to build everything yourself. Retailers should consider engaging in partnerships with platforms where their customers are already interacting at scale versus trying to build such capabilities on their own. Through these partnerships, retailers can gain access to the kind of detailed, real-time data they need to craft a truly customized customer experience.

- Revamp your organization’s financial structure, organizational structure, operating structure, and ecosystems to support agility and responsiveness to customers’ needs. Planning and budgeting functions could be a good place to start.

- Embrace category differences and recognize that digital initiatives appeal differentially across customer segments and merchandise categories. Every investment, prioritization, and decision should be evaluated at both the customer and category levels.

- Wherever possible, use digital to enable customers to lead their own journey rather than making them step through your store layout or merchandise hierarchy to find and buy products.

- As the growth of digital slows, recognize that market share needs to be pursued more surgically. Retailers should focus on understanding where share gains will come from and specifically on what experiences they will need to focus to be able to win customers.

- Most importantly, to drive sales growth, retailers should refocus on innovating around product offerings and the customer experience. We believe that the primary source of differentiation and competitive advantage in today’s environment will be leveraging the store footprint to help customers find, select, purchase, and receive products. For example, brick-and-mortar retailers have an opportunity to begin to better drive in-store foot traffic to online sites—through the quintessentially low-tech mechanism of signage. Anyone who is running an e-commerce business today knows how expensive it is to buy online traffic, but for retailers with physical locations, our research shows that in-store signage is a far more powerful influence than social media.

Brick-and-mortar retail companies face formidable competition from e-commerce players; yet traditional retailers need not give up the battle for growth. By seeking an in-depth understanding of their own customers and by using their physical assets to their advantage, retailers can put in place strategies for customer engagement that allow them to thrive.

Appendix: Methodology

Retail volatility index methodology

Concentration index methodology: The Gini coefficient is used to indicate how the distribution of retail market share has changed from 2007–2015 for the top 120–140 retailers in 2015.

Market concentration is a useful index as it indicates the degree of competition in the market. To measure market concentration in this study, the Gini coefficient was used to indicate how the distribution of retail sales has changed within the top 120–140 retailers from 2007–2015.

A Gini coefficient ranges from 0 (market share is distributed evenly across all firms) to 1 (one firm has all sales). It is a function of the number of firms and their respective shares of the total sales. It is calculated as the mean of the difference between every possible pair of data points, divided by the mean of all the data points.

Deloitte volatility index methodology: The volatility measure is based on year-over-year weighted standard deviation of market share change.

Standard deviation is often used to measure historical volatility of price related to a financial instrument over a given time period. For this study, standard deviation is applied to measure the historical volatility of market share for the top 120–140 retailers from 2007–2015.

A higher volatility over time can be interpreted as increased market share volatility within the top 120–140 retailers. An increase in market shares being “traded” versus a lower volatility over time reflects lower market share volatility or less market share being “traded.”

Digital influence survey methodology

This survey was commissioned by Deloitte and conducted online by an independent research company on April 25–May 5, 2016.

The survey polled a national sample of 5,014 random consumers. Data were collected and weighted to be representative of the US Census for gender, age, income, and ethnicity. A 95 percent confidence level was used to test for significance.

Below are the margins of error for the specific sample sets in this study:

- National random sample: 95 percent confidence, margin of error 1–2 percent (+/-)

- Device owners: 95 percent confidence, margin of error 1–2 percent (+/-)

- Smartphone owners: 95 percent confidence, margin of error 1–2 percent (+/-)

Additionally, subsets of randomly assigned respondents were asked to provide information about how they use a digital device to shop for a product sub-category (such as cosmetics or perishables). Sample sizes ranged from 160–164 (95 percent confidence, margin of error 7–8 percent [+/-]). Specific digital behavior data represent consumers who use digital devices to shop.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.