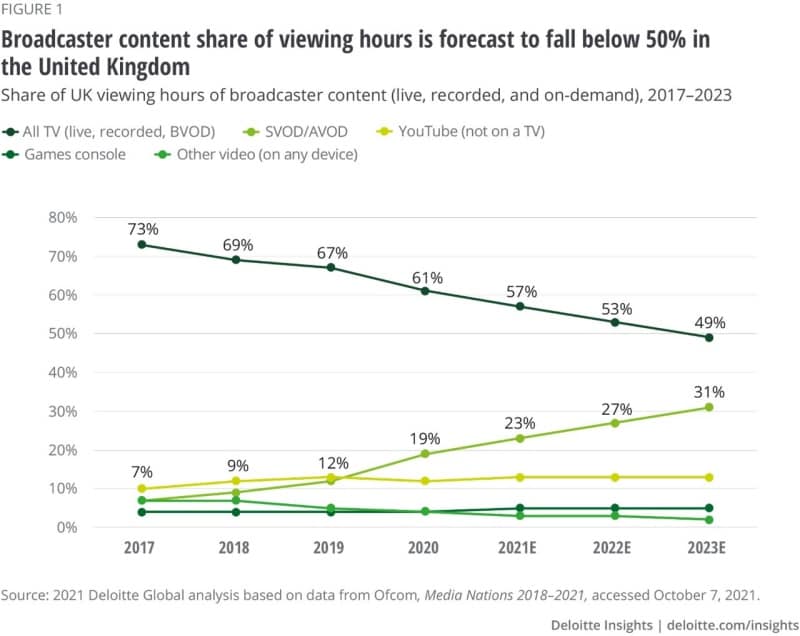

Despite TV’s imminent fall from its historic dominance, its ebbing share of video viewing is hardly a death knell. TV ad revenues have largely held up despite the decline in hours watched. Between 2010 and 2019, TV viewing hours fell by 21% across all viewers in the United Kingdom,16 but ad revenues declined by only 14%, from £5.8 billion to £5 billion.17

The main reason for this is that TV is still the only game in town when it comes to aggregating the large audiences that matter to major brands. TV’s reach remains unmatched: 20 million people in the United Kingdom watched YouTube on TV sets during March 2020, but while impressive, that’s far lower than TV’s 91% peak weekly reach in the same month.18 Granted, single TV shows with truly gigantic audiences are less common than they were a decade or so ago. In 2010, 170 ad-funded TV programs in the United Kingdom attracted more than 10 million viewers; in 2020, that number had dropped to 30. But in that same year, fully 569 programs boasted 5–10 million viewers each on ITV (the United Kingdom’s largest broadcaster) alone.19 No other medium comes close to this size of audience.

On the other hand, TV may find it increasingly difficult to maintain pricing for ad time that delivers acceptable value to advertisers. TV broadcasters over the past decade have been making up for revenue lost due to shrinking viewing hours by raising ads’ price per thousand people reached, especially among younger demographics. If TV viewing continues to fall and the cost per thousand viewers continues to rise, advertisers may be compelled to seek alternatives. This will likely be broadcasters’ preeminent concern over the next few years in any market seeing declines in viewing share similar to those forecast for the United Kingdom.

How can TV sustain itself under these circumstances? One response would be to create a single measurement system that aggregates viewing behavior across all forms of television, whether live, time-shifted, or on demand. The United Kingdom’s CFlight is such a system, though it is so far unique, and broadcasters elsewhere will face challenges in replicating it: CFlight took two years to develop and required collaboration among companies that had previously competed for decades. Broadcasters could also offer advertisers campaigns that include inventory on the third-party video-on-demand services that have made the most gains in viewing time, especially among those watching on a TV set. A third tactic would be to analyze the efficacy of advertising by size of screen and type of media, betting that TV will come out ahead. While any screen can show video, the impact of an ad shown on a 50-inch screen, with sound to match, will typically be far greater than one shown on even the largest smartphone, with sound muted.

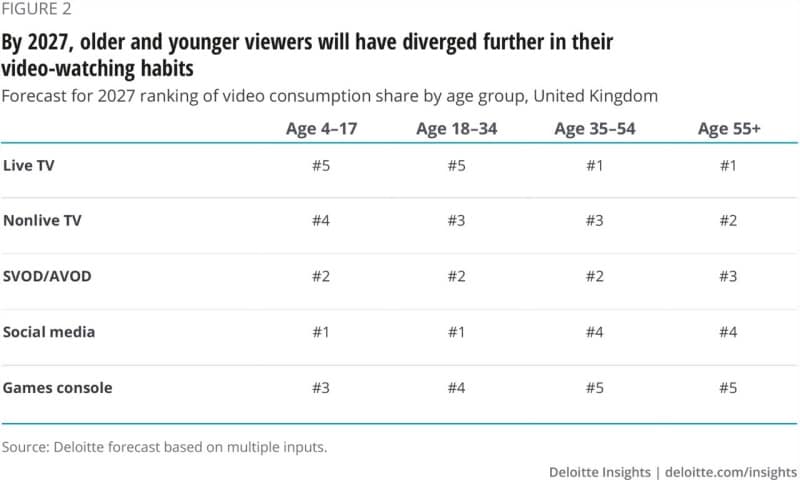

For TV to thrive going forward, the industry should regroup to face the new reality that it will be, not the dominant form of home video entertainment, but only one of many strong contenders for viewers’ attention. Its market position is still strong, and its viewing experience is still compelling, and TV broadcasters may be able to make content for global VOD companies, but the industry should make sure it does the best job of selling its strengths.