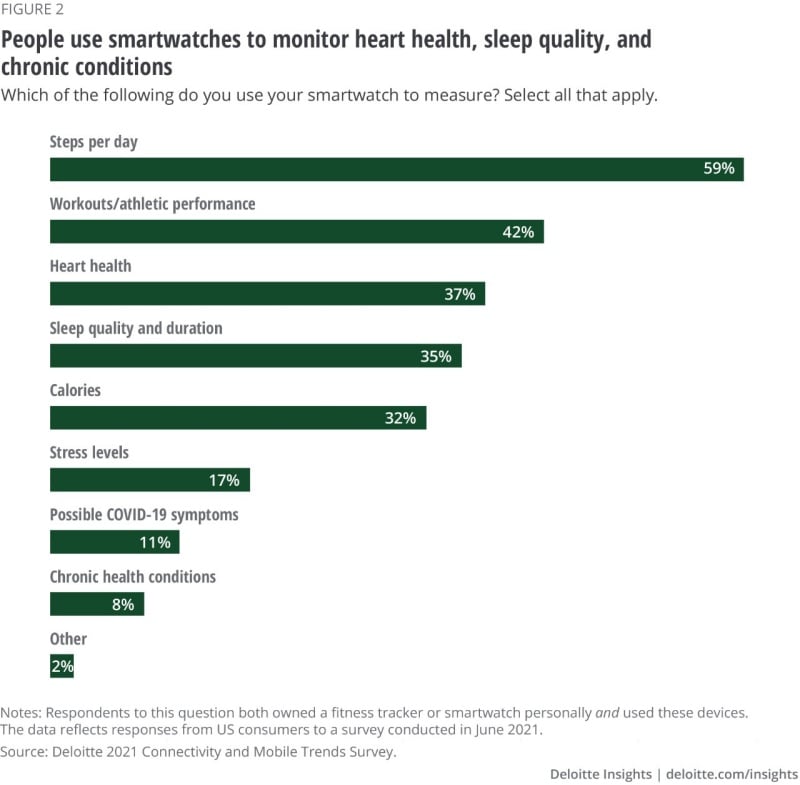

Smartwatch innovation is progressing rapidly, driven by advances in sensors, semiconductors, and AI. For example, some smartwatches now feature optical sensors that continuously measure variations in blood volume and composition using a technology called photoplethysmography (PPG). Algorithms produced and continually improved via machine learning use data from these sensors to provide insights into users’ activity levels, stress, heart pattern anomalies, and more.4

As another example, companies are getting closer to enabling smartwatches to monitor blood pressure, using PPG and other technologies such as Raman spectroscopy, and infrared spectrophotometers.5 Measuring blood pressure with a cuff is inconvenient and uncomfortable. Most importantly, periodic blood pressure measurements can miss signs of chronic hypertension, which can cause heart disease, heart attacks, and strokes. Accurate, continuous, unobtrusive blood pressure measurement could expand the smartwatch market: 1.3 billion adults worldwide suffer from hypertension.

Of course, there are limits to what current smartwatch sensor technology can do without attaching to—or getting under—a person’s skin. That’s where smart patches come in.

Smart patches, developed mostly by medtech companies, are typically small and unobtrusive, affixing directly to a person’s skin. Some “minimally invasive” smart patches use microscopic needles that painlessly penetrate the skin to act as biosensors and sometimes to deliver medications.

Unlike smartwatches, which provide a broad range of health data and insights, smart patches are typically designed for a single indication such as diabetes management, patient monitoring, and drug delivery. Smart patches also employ a broader range of technologies. For example, smart patches that measure heart rate variability often use electrocardiogram technology that tracks the heart’s electrical activity directly and more accurately than smartwatches.6

Smartwatches and smartphones still play an important role. Data from smart patches is being integrated with smartwatch and smartphone apps, sending data to these devices for display and analysis. With the right technology, including interoperability capabilities, doctors could see wearable health data on a patient’s health record, gaining access to more comprehensive information to inform diagnosis and care.