Smart speakers: Growth at a discount TMT Predictions 2019

15 minute read

11 December 2018

Smart speakers, already a rapidly growing market in English-speaking countries, are poised to invade the non-English-speaking world in 2019 and beyond—setting the stage, in the long term, for making computing accessible to all.

Deloitte Global predicts that the industry for smart speakers—internet-connected speakers with integrated digital voice assistants—will be worth US$7 billion in 2019, selling 164 million units at an average selling price of US$43.1 We expect 2018 sales of 98 million units at an average of US$44 each, for a total industry revenue of US$4.3 billion. This 63 percent growth rate would make smart speakers the fastest-growing connected device category worldwide in 2019, and lead to an installed base of more than 250 million units by year-end.2 Robust sales performance in 2019, although high, will represent a deceleration from the prior year: In Q2 of 2018, smart speaker sales were up 187 percent year over year.3

The opportunities: What will drive smart speaker growth?

Learn more

Listen to the related podcast

Watch the video or view the infographic for this prediction

View TMT Predictions 2019, download the full report, or create a custom PDF

Smart speakers have, literally, a world of opportunity for growth. Much of that opportunity comes from expansion into non-English-speaking countries. At the end of 2017, smart speaker sales were largely confined to English-speaking markets, with more than 95 percent of sales in the United States and the United Kingdom.4 By the beginning of 2019, however, these speakers will be spreading their linguistic wings, and sales should take off in countries in which the majority of the population speaks Chinese (Mandarin or Cantonese), French, Spanish, Italian, or Japanese, as well as English. In most of these geographies, the smart speaker category is likely to enjoy the fastest growth in ownership and shipments relative to other smart devices.

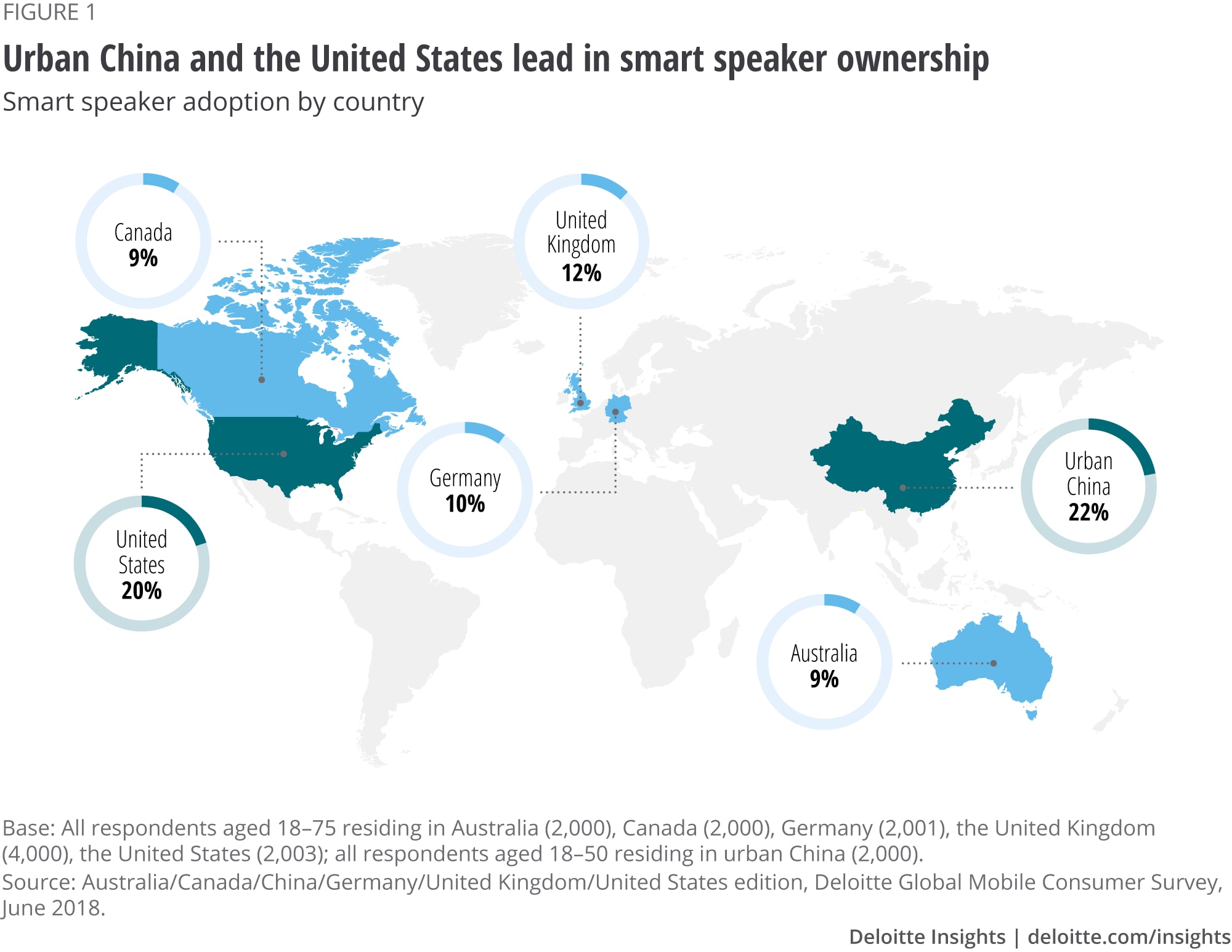

Sales in non-English-speaking countries will likely further expand a rapidly growing user base. Already, the worldwide installed user base exceeds 100 million units as of the start of 2019.5 According to Deloitte research, the smart speaker was the device with the highest year-over-year increase in ownership through mid-2018 in six of the seven markets in which they were available from multiple major brands (urban China, the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, with only Germany lagging).6 As of mid-2018, penetration of smart speakers was highest in urban China, with 22 percent of adults having access to a smart speaker, followed by the United States, with 19 percent of adults having access to one (figure 1). In these markets, the smart speaker was also the fastest-growing of all emerging connected devices.

Localization may place some constraints on smart speakers’ global expansion. Creating support for new languages is likely to be capital- and time-intensive due to the complexity of spoken languages.7 In China, there are 130 spoken dialects.8 In India, while most people speak Hindi, there are roughly 10 different variations of that language, and the amount of Hindi content available for machine learning is limited. According to one analysis, 90 percent of all digital voice assistants in India support only English.9 But these issues are not insurmountable, and the size of these markets provides ample incentive for smart speaker manufacturers and voice recognition capability creators to spend the time and money to address them.

In addition to wider language support, smart speakers are improving in speech recognition accuracy, enhancements that can be applied and amortized across a widening range of devices. Google’s word error rate for English speech recognition, for instance, has steadily declined from 8.5 percent in July 2016 to 4.9 percent in May 2017.10 Further, machine learning is now allowing smart speakers to narrow the accent gap: In their early years, smart speakers understood standard English well, but could be befuddled by strong regional or national variations, or English spoken by nonnative speakers, with accuracy up to 30 percent lower.11

Smart speakers’ complexity and build cost are also declining, partly due to a reduction in the number of microphones required per device. By using neural beamforming, Google was able to ship its Home smart speaker using just two microphones, rather than eight as originally planned, with no resultant decline in accuracy.12 The microphones themselves are also improving due to the emergence of piezoelectric microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) technology, which consumes less power than earlier technologies. While most current smart speakers need to be plugged in (as opposed to being battery-powered), as they are constantly powered up and listening for a spoken trigger,13 MEMS microphones use almost no power until activated by the wake word. This new microphone technology enables digital assistants to be more readily incorporated into battery-powered speakers.

So 2019 will likely be a strong year for smart speakers with robust growth in unit sales. But what are their longer-term prospects?

Potential demand for smart speakers could be in the many billions of units, possibly even higher than for smartphones. A speaker could be installed in every room in a house or a hotel, every office in a building, every classroom in a school, or every bed in a hospital.

Several hotel chains have undertaken mass deployments of smart speakers, whose applications include serving as in-room concierges. The Marriott International Group plans to deploy Amazon’s and Alibaba’s smart speakers in some of its hotels;14 100,000 units will be deployed in China alone.15 The Wynn Las Vegas has installed smart speakers in all 4,748 of its rooms.16 If this trend continues, many of the world’s estimated 187,500 hotels and 17.5 million guest rooms17 could feature smart speakers or voice control within the next decade.

Drive-through restaurants could use voice automation to take orders. This would free up workers from having to manually process orders. In the United States alone, there are more than 12 billion drive-through orders per year.18

One hospital in Sydney, Australia has piloted the use of smart speakers as an upgrade to a bedside call button.19 Unlike a call button, smart speakers allow patients to specify requests. The smart speaker can handle simple tasks, such as turning on the television, lowering the blinds, or turning down the lights, via voice commands from the patient, saving time and labor. If a patient just needs an additional pillow, a junior staff member could get it, leaving nurses and doctors to focus on tasks that require their specialized skills. If a nurse or doctor were needed, the patient could describe their symptoms, which would enable the staff to prioritize requests. The appropriate medical staff member would be notified, and the patient would be reassured (via the speaker) that someone was on the way.20

In some contexts, voice can be the most natural and productive way to communicate with a computer. When one’s hands are occupied operating machinery, typing with both hands, holding an infant, or cooking, voice may be the most convenient option. While driving, voice may be the safest option as well.21

Indeed, in many workplaces, including theaters, factories, chemical labs, and restaurant kitchens, smart speakers may make operations safer and more precise than they are today. Deloitte Global believes that in the long term, the number of smart speakers in the workplace might exceed the number in homes, and the value of the tasks they do may be orders of magnitude greater than playing music, hearing the weather forecast, or asking what zero divided by zero is.

Further, for the visually impaired, smart speakers can be an additional, more convenient way to access computing power. For many of these people, speaking a search query to a machine that can always be on, and that has an array of microphones listening for commands, may be easier than using a smartphone or touch-typing on a computer keyboard. The potential market is large: More than 250 million people in the world are vision-impaired, of whom 36 million are fully blind.22 The vast majority of the visually impaired are age 50 or older, and as such, they may be less comfortable using a computer or smartphone than they would simply speaking to a machine. That said, while the visually impaired may be more likely to have multiple speakers per home (one in each room) than sighted people, they may also be more price-sensitive, with one-half being underemployed or unemployed and earning less than US$20,000 per year.23

Smart speakers may also be the way in which illiterate people are able to access the Web. About 14 percent of the world’s adults—about 700 million people24—cannot read.

The caveats: What could slow smart speaker growth?

While there is plenty for smart speaker makers to be optimistic about, there are also grounds for caution. While 2019 will likely be a good year for the product, the market’s growth will likely be only one-half what it was in 2018, and a further decline in subsequent years is possible.

The initial demand for smart speakers has been driven heavily by price promotion. In the United States, entry-level devices, which likely represent the majority of units, have been priced as low as US$25 per device during promotional periods.25 In China, promotional prices of US$15 have been available.26 For example, Alibaba’s Tmall discounted the price of its Genius X1 by 80 percent to RMB99 (US$14) from RMB499 (US$70); it sold one million units at this price.27

It is possible that these discounted prices may not be sustainable in the long term, constraining demand. Already, smart speakers are something of a luxury item; ownership or access to smart speakers in the United Kingdom was twice as high among individuals earning more than £50,000 (US$65,250) than those below that threshold.28 It may be that for those on lower incomes, a smart speaker would need to be very useful indeed to become a must-have product, especially if sold at full price. Some analysts have concluded that most smart speakers today may be being sold at cost or at a loss, based just on the cost of their components.29 This suggests that there may be little further scope for the price of smart speakers to fall much further.

The demand curve for smart speakers may also be being somewhat artificially shaped by the integration, by default, of voice assistants into all wireless speakers. For instance, Sonos, one of the wireless speaker market’s pioneers, now incorporates support for Amazon’s Alexa across many of its products.30 Buyers may be purchasing more expensive smart speakers primarily for their audio quality, with their voice assistant capability being of relatively little value to them. Yet revenues for these higher-end devices would be categorized as smart speaker revenues, potentially flattering the revenue line.

The provision of free over-the-air upgrades may also dampen demand for upgraded smart speakers among existing owners. For example, additional language support can be installed through a software upgrade, making the device more useful, at no incremental cost to the user.31

Demand for smart speakers will likely be driven by utility. It is worth noting in this regard that, even though digital voice assistants, which are core to smart speakers, have been available on a range of devices for several years—and are installed on tens of billions of consumer devices today—the majority appear to be little used. According to Deloitte’s research, most voice assistants on smartphones, tablets, and computers have never been used (figure 2). In fact, the only product type for which the majority of owners have used a voice assistant is the smart speaker, since they cannot be controlled without using the voice feature.

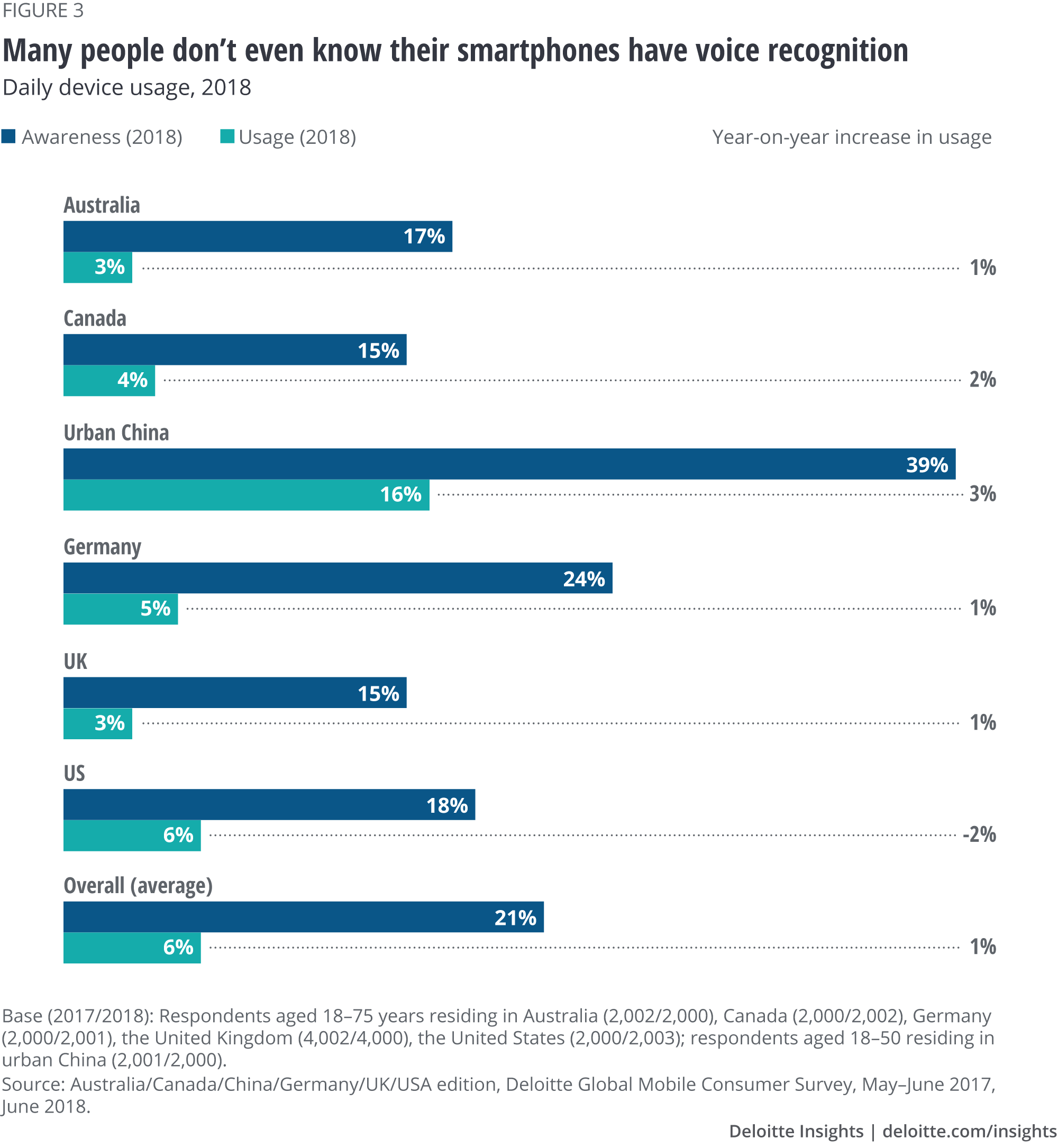

The challenge is not just getting people to try out voice assistants, but their general (historic) disinterest in voice recognition per se. Figure 3 shows the extent of usage of voice recognition in a number of major markets. For all countries represented in the figure, smartphone penetration exceeds 75 percent. Yet awareness of the smartphone’s voice recognition capability is low (averaging 21 percent), and usage is even lower (averaging 6 percent). And although usage is growing, it is only growing by 1 percentage point per year on average, and that is from a very low base.

One measure of utility is the frequency of usage. Here, smart speakers perform better, but only marginally better. In the six countries represented in figure 3, most smart speakers are used daily, but it is a slender majority. Indeed, based on a sample of countries with relatively mature smart speaker markets, these devices are only the seventh-most used device on a daily basis (figure 4).

The smart speaker’s usefulness also partly depends on the range of applications for which it can be used—or, often, how people actually use them. In most markets so far, they have most commonly been used to play music, which arguably is not that disruptive: Devices that emit sound have been around since the 19th century. In fact, Deloitte research from mid-2018 showed that smart speakers’ No. 1 application across five countries was to play music (figure 5)—except in Canada, where checking the weather was the top usage; in most other markets, weather was the No. 2 application. Possibly, checking the weather via a spoken command is an improvement over requesting the weather on a smartphone app, but is it enough of an improvement to drive smart speaker sales?

Some people may even prefer selecting music with an app to dictating the name of a track in a playlist. Given that smart speakers’ third-most common use in several markets is setting up timers or alarms, the combination of music, weather, and alarm-setting makes smart speakers look much more like an updated bedside or kitchen radio than a fundamentally disruptive device.

Bottom line

Smart speaker sales to both new and existing users should grow strongly in 2019, and also likely in 2020. For the market to continue growing beyond then, however, the device should have multiple applications beyond just playing music or speaking a weather forecast. It needs to become more useful, more often. More applications and better accuracy will likely be key to market growth.

Smart speakers are more than just another product category, however. They are also likely to serve as an important introduction to voice assistants. Indeed, in the medium term, one of the key roles that smart speakers may play is to increase people’s familiarity with voice assistants, as well as to help improve voice recognition capabilities.

Smart speakers may provide the first experience many consumers—especially younger family members—have of voice recognition. Some people may be reluctant to use voice recognition technology on a smartphone, but may be willing to try out voice interfaces on a smart speaker in the seclusion of their homes. Once comfortable with the technology, these people may subsequently become more frequent users of voice recognition across a range of environments, from cars to connected homes to call centers. All major smart speaker vendors have their own digital assistants, and this core technology can be deployed in multiple types of devices.

Nor is this the smart speaker’s only potential broader benefit. The more that smart speakers and other voice recognition devices are used, the better voice recognition will likely become. Seeding the smart speaker market with devices priced near cost may be the fastest way to generate billions of samples of dialogue that can be used to support ever better voice recognition capabilities across a wide spectrum of devices.

Smart speakers—and, more widely, voice assistants—will almost certainly find myriad applications in the enterprise space. The ideal situation for them is in a not-too-noisy room where someone has their hands busy. This does happen at home (while cooking or changing a baby, for instance), but not on the scale that it happens in operating rooms or on factory floors. Voice recognition will likely be an ideal way of mechanizing repetitive processes such as taking orders in a drive-in restaurant or reserving spaces in a shared office.

Considering all this, it is probable that, over time, people will end up talking to speakers (and other machines) much more than they do today. Voice may never become the dominant user interface with technology, but it is very likely to become a core one, particularly for those who are vision-impaired and/or may struggle with keyboards or small buttons. And while voice recognition does not work well in all contexts and environments, the same could be said of keyboards and mice, which cannot readily be used on the move and need two hands to operate, or touchscreens on smartphones and tablets which need at least one free hand to use.

While voice recognition can be challenging, the long-term benefits are significant. Whether on a speaker or any other device, voice recognition and voice assistants open up the benefits of computing to everyone. For the Web to be truly worldwide, there are two options: to make the whole world literate, or to offer voice-enabled computing to everyone. The latter approach may be easier.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the collection

-

Quantum computers: The next supercomputers, but not the next laptops Article6 years ago

-

Radio: Revenue, reach, and resilience Article6 years ago

-

Does TV sports have a future? Bet on it Article6 years ago

-

3D printing growth accelerates again Article6 years ago

-

Smart speakers: Growth at a discount Article6 years ago