A movement in the making has been saved

A movement in the making

25 January 2014

What makes “making”—the next generation of inventing and do-it-yourself—worth paying attention to?

Executive summary

“Making”—the next generation of inventing and do-it-yourself—is creeping into everyday discourse, with the emerging maker movement referenced in connection with topics ranging from the rebirth of manufacturing to job skills development to reconnecting with our roots. As maker communities spring up around the globe, a plethora of physical and virtual platforms to serve them have emerged—from platforms that inspire and teach, to those that provide access to tools and mentorship, to those that connect individuals with financing and customers. At the same time, access to lower-cost, small-run manufacturing, particularly in hotspots such as Shenzhen, China, has increased, making small production more economical and viable.1 Both the supply and demand curves are being affected—the long tail of supply can now meet the long tail of demand, and the long tail of demand itself is changing as individuals change their own consumption.

The scales haven’t tipped yet. While alternatives exist to almost any mass-produced item, most US consumers haven’t yet explored the full range of possibilities. However, it is only a matter of time before large firms begin to feel the impact of this changing landscape.

The maker movement is an important manifestation of the economic landscape to come. Companies would be well served to find ways to participate, learn, and perhaps shape the movement. The maker movement brings disruptions but also opportunities: to boost sensing capabilities, leverage platforms for R&D, accelerate learning, and reimagine the enterprise as a platform.

In this report, we explore the three categories of makers, the ecosystem growing around those categories, the role technology plays in this ecosystem, and, finally, how business can take advantage of the opportunities this movement represents.

In a cavernous Silicon Valley event center on a sunny March afternoon, the aisles are filled with color and movement and a pervasive sense of wonder. And people. Tens of thousands of people crowd shoulder to shoulder to experience high- and low-tech gadgetry. Walls of LED lights brighten one end of the darkened warehouse, while at the other a metal-suited guitarist plays with lightning set off by giant Tesla coils. In the adjoining warehouse, crowds gather to watch 3-D printers produce small plastic objects from the bottom up, while synchronized quadcopters buzz overhead. In the distance, a dragon mobile breathes fire.

Everywhere you look, it seems, people of all ages are taking things apart and testing new ways of putting them back together. This is Maker Faire.

Welcome to the world of the maker.

What makes a “maker”?

Craftspeople, tinkerers, hobbyists, and inventors can all be considered makers. As Chris Anderson puts it, “We are all born makers.”2 Broadly, a maker is someone who derives identity and meaning from the act of creation. What distinguishes contemporary makers from the inventors and do-it-yourselfers (DIY-ers) of other eras is the incredible power afforded them by modern technologies and a globalized economy, both to connect and learn and as a means of production and distribution. Powerful digital software allows them to design, model, and engineer their creations, while also lowering the learning curve to use industrial-grade tools of production. Makers have access to sophisticated materials and machine parts from all over the globe. Forums, social networks, email lists, and video publishing sites allow them to form communities and ask questions, collaborate, share their results, and iterate to reach new levels of performance. Seed capital from crowdfunding sites such as Kickstarter, cheap manufacturing hubs, international shipping, and e-commerce distribution services such as Etsy and Quirky help makers commercialize their creations.

Today’s makers can create hardware capable of exploring the deep ocean, going to space, and solving critical problems that were previously the domain of large, well-funded organizations. They invent new solutions, bring innovations to market, and derive meaningful insights through Citizen Science.3 They share, inspire, and motivate, and in the process, they are reshaping education, economics, and science. As Ted Hall, CEO of ShopBot Tools, puts it, “The DIY-er is now less of a putterer and more of a player.”4

The act of making is not new. Many of the people at the Faire used to do this in their garages, basements, and workshops. For millennia, people have been manipulating objects to suit their needs and transform the world around them. Our built world and the many inventions and innovations that populate it are testament to the long history of making.

What is new is how modern technologies, globalization, and cultural shifts are enabling and motivating individuals to participate in making activities and removing barriers all along the value chain, from design and prototype to manufacturing to selling and distribution.

With greater access to tools, training, and community, not to mention the technology-guided tools themselves that are less expensive and easier to use, the hurdles to creating are disappearing. Access to suppliers, customers, and funding makes it easier for individual makers to reach a broader audience. The same forces that are democratizing information—improved cost-performance of technology driving digitization and connectivity—are also lowering the cost to produce physical objects. Never before has it been so easy to create or modify something with minimal technical training or investment in tools. This allows more people to develop their ideas into tangible prototypes and begin to test their prototypes with potential customers. Events like Maker Faire accelerate this sharing and testing of ideas and techniques, allowing individuals to come out from the garages, to inspire and be inspired, and, for some, to discover an audience.

It is tempting to dismiss the maker trend as a fad. Employees of large firms are mostly unaware of the platforms and tools makers are using. Even when they know of them, the rigid processes and rules that they work under, and their own mindsets, can prevent corporate employees from taking advantage of the opportunities presented.

See endnote 5

See endnote 5

Yet early projects from the movement have already had a disruptive impact (figure 1). Pebble, a start-up that makes smart watches, began with founder Eric Migicovsky creating watch prototypes in his dorm room. With a Kickstarter campaign that raised more than $10 million, the Pebble watch generated excitement in a category of wearable computing that had not yet captured the interest of the consumers—it also caught the attention of large players such as Samsung and Google to accelerate their investments in the wearables category.6And they aren’t the only ones: Companies from GE and Ford to Nordstrom and Ikea are testing new models of engagement with the movement. For example, Autodesk has invested in making its professional-grade design software available on desktops everywhere, and, with its acquisition of Instructables, the company places itself amid the amateur market, deeply engaging with makers at multiple levels.

The current maker movement, with its bent for “open source hardware,” has parallels to the open source software movement. By enabling collaborative programming, the open source movement fundamentally changed the way software was developed, allowing for greater development speed and more robust solutions. But open source also had broader implications for organizations and technology. Sylvia Lindtner, a techno-cultural ethnographer at the University of California, Irvine, draws a connection between the institutional form born out of collaborative programming to “maker spaces,” the physical facilities where makers gather to learn and create: “Open source is . . . a new institutional form, with all its regional, technological, organizational, and political consequences. Similarly, when we turn our attention to hacker spaces, we see not only a space experimenting with new sorts of fabrication tools, but also a community that reshapes the very meaning of technology innovation.”7

With the groundswell of global participation, the maker movement on its own is interesting. As a precursor of a broader shift in the global economic landscape, it is doubly so.

Open source hardware opens the door for newcomers by undermining the proprietary foothold of a larger competitor. With design and technical specifications available online, hardware developers can modify existing hardware and do rapid prototyping and small-scale production runs. Arduino was arguably the first open source hardware project that allowed anyone to replicate the device, but with the requirement that users obtain a license to use the Arduino name.8 Currently, in 3-D printing, even some people who have made a business of creating and selling physical objects still freely share their design files. The dynamics of open source hardware are still evolving.

With the groundswell of global participation, the maker movement on its own is interesting. As a precursor of a broader shift in the global economic landscape, it is doubly so.

In the evolving maker movement, scale and fragmentation interact symbiotically. On one hand, the technological advances that make it easier and cheaper for an individual to create an item and take it to a broader audience are enabling a proliferation of smaller businesses. Meanwhile, as the number of small businesses grows, the need for large-scale providers—for example, of logistics, design tools, and marketplaces—to serve the fragmented businesses increases as well.

These dynamics will affect each industry differently. Industries such as consumer products may feel the effects early on. Similar to the Internet, however, the impact of the maker movement will eventually permeate society, shifting identity and meaning from consumption to creation and blurring the boundaries between consumers and creators. These makers are the consumers of the future and likely the future of consuming.

This future calls for companies to imagine ways to serve as a platform to connect far-flung consumers with the products they desire. It means designing new products and services with the help of the people who will ultimately benefit from them. This focus on platform is even more important given the proliferation of new products and the decreasing useful life of any one product. Companies may also need to reconsider work—the way it is parsed out and managed—to better benefit from the creative impulse of the workforce.

In this future, it is easy to imagine that unless companies take the lead, grassroots efforts may fill the evolving need for new products and services. Companies can choose to participate or retrench, but those that close themselves off will be susceptible to disruption driven by no less a force than humans’ intrinsic desire to create.

Journey of one, journey of many

Makers and the maker movement represent a microcosm of broader trends in today’s world. Yet, with the ever-growing number of participants around the world, there is no single maker profile. Dale Dougherty, editor and publisher of Make magazine, first categorized makers into three broad stages: Zero to maker, maker to maker, and maker to market.9 Not all makers will move through all three stages, nor will they want to—the power of the movement is that there are as many end points as there are entry points.

Makers and the maker movement represent a microcosm of broader trends in today’s world.

Zero to maker: Every maker has a different starting point. Some have tinkered all their lives, while most are rekindling or discovering a fondness for altering the world around them. The journey begins with inspiration to invent, the spark that turns an individual from purely consuming products to having a hand in actually making them. The inspiration can come from anywhere, from imagining a new approach to an everyday task (such as separating an egg yolk) to immersion in a new environment such as Maker Faire. To go from zero to maker, the two most important aspects are the ability to learn the required skills and access to the necessary means of production. Knowing that others have done it makes it easier to take this step. What renders making less daunting is easier access to sources of inspiration and learning. Such sources have proliferated as a result of digitization and increasingly cheaper tools of production. Makers can more easily access stores of information—both in physical settings such as local workshops and in virtual settings such as online community portals—to fill gaps in knowledge and capabilities. Moreover, people can now access otherwise cost-prohibitive tools through sharing communities and hacker spaces, such as TechShop, Artisan’s Asylum, and Fab Lab Barcelona, as well as spaces created by libraries, universities, and even museums. The transfer of knowledge from the expert to the novice inspires more people to become involved and move from zero to maker.

David Lang: Zero to maker

David Lang: Zero to maker

David Lang, poster child of a budding maker, recounted his transformative experience visiting Maker Faire for the first time in 2011. David never considered himself a maker: “I was the kid that saw a toaster and video player and accepted that one was made to make toast and the other to play videos. Neither was meant to be taken apart.” However, the awe and envy he experienced at the Maker Faire challenged his belief that he wasn’t a maker, and he resolved to learn to be one.

David set out to take every class at TechShop, and he blogged about his experience on Makezine, the online portal for Make magazine. To help others on this path, he published the knowledge and information that he accumulated in a book called Zero to Maker: Learn (Just Enough) to Make (Just About) Anything (2013), which he describes as a Lonely Planet guide to the maker movement.

One of the many other makers he met along the way was Eric Stackpole, who was tinkering with a submersible robot. David and Eric went on to cofound OpenROV, an open source underwater robot, funding the initial build of the robot through a Kickstarter campaign. All of the hardware and software specifications for the robot are open, attracting an array of individuals, from academics to amateur oceanographers, who are working together to create more accessible, affordable, and powerful tools for underwater exploration. This community’s rapid iterations and distributed development have dramatically improved the robot’s performance in a short period of time.

As David once said on stage, “Don’t let not knowing what you are doing get in the way.”10

Maker to maker: The distinction in this stage is that makers begin to collaborate and access the expertise of others, whether by formally building teams around projects or by simply asking for help from others who are willing to share their experience. At this stage, makers also contribute to existing platforms. Here, too, powerful undercurrents are at work, both from technological revolution as well as unleashing the innate desire for self-expression and creation.

Historically, makers tended to connect in small communities limited by interest and geography, which were neither accessible to outsiders nor welcoming to newbies. The advent of the Internet changed that. Communities can now connect and share passions without limitation of distance, and individuals can move among communities rather easily, choosing their level of participation.

The maker community has begun to organize talent pools (for example, in drones and 3-D printing), where a group meets both online and in person to share work—a bit like the original Homebrew Computer Club. Expertise is categorized by interests and projects rather than academic credentials or job titles, and relationships are created ad hoc.

On this portion of the spectrum, makers start to connect with one another through the same virtual and physical platforms that existed to draw people into the movement to begin with. Fragments of knowledge begin to concentrate, while more knowledge is developed in a decentralized fashion as new makers build on the foundation previously established. As makers become a deeper part of and more invested in communities of making like Maker Faire, their journey can branch out into multiple paths to include the discovery of marketplaces or finding better ways to produce their inventions. The desire to improve and share with others catalyzes the move to maker to maker.

Dale Dougherty: Maker to maker

“This feels like the early days of [the] Web. . . There’s something here about being a movement. It’s not just a fad or trend.”

As founder and CEO of Maker Media, Dale Dougherty is arguably the symbolic father of the maker movement. His perspective reflects the enthusiasm and commitment of the fast-growing movement. From the commercial successes to those driven by a pure hacking ethic to the esoteric creative gems, makers come in many flavors, but their stories share a sense of a larger commitment to the community.

Rather than having a definitive end or a limited number of participants, the maker community seems able to absorb a great diversity of people and pursuits. Dale coined the terms “zero to maker,” “maker to maker,” and “maker to market” to describe the breadth of opportunities to participate. He points to the difference between finite and infinite games described in James Carse’s book Finite and Infinite Games: “A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.”11 An infinite game invites anyone who is willing to play to join in.

With this notion of open-ended play in mind, Dale built two of the largest platforms that sustain the movement—Make magazine and Maker Faire. On the back of those platforms, he created a detailed playbook to support the creation of maker spaces around the globe; created Maker Shed, a marketplace for kits and equipment to stock the maker space or allow the fledgling maker to get started; and most recently, to provide more opportunities to young makers, launched the nonprofit Maker Education Initiative and advocated for maker spaces inside institutions such as libraries and science centers. Each of these platforms is an open-ended invitation to the community to participate in creating and recreating, setting the stage for an infinite game.

Maker to market: From the workshops and the digital communities, a new wave of invention and innovation springs forth. Knowledge flows and concentrates and flows again. Some of the inventions and creations will appeal to a broader audience than the original makers. Some may even find commercial appeal. In this part of the spectrum, makers take deliberate steps to formally introduce their inventions to the commercial part of the spectrum.

It is by no means the destination for all makers. Many will continue to improve on their own inventions without a profit motive. However, even if only a few makers pursue market opportunities, the impact may be huge.

During a recent trip to the electronic markets in Shenzhen, well-known maker bunnie Huang noted, “There are 100 million factory workers in the region. If 1 percent of those factory workers decide to leave factories and begin their own operations, there are one million new specialists. If 1 percent of those specialists decide to develop original creations, then there are 100,000 new inventors. If 1 percent of those inventors find commercial success, then there are suddenly 1,000 new commercially viable products in the marketplace.”12

This is where the maker movement collides with the business world. This decision to scale and profit catalyzes the move from maker to market.

bunnie Huang and Eric Pan: Maker to market

“I don’t want the whole LED—how much would it cost to get the IC [integrated circuit] embedded in here?”

We were on the LED floor inside the Huaqiangbei electronics markets in Shenzhen, and Andrew “bunnie” Huang, founder of Chumby and hacker extraordinaire, was learning and negotiating at the same time. bunnie continued a rapid exchange of Mandarin with the middle-aged woman sitting in an eight-by-eight-foot space behind a glass counter, who was on the phone with the factory that manufactures the LEDs. On this day, bunnie was acting on behalf of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate student, Jie Qi, who was building Circuit Stickers, a line of stickers with conductive electronic parts for kids (and adults) to make electronic art.13

On another day, Eric Pan, founder and CEO of Seeed Studio, explained how his company helps makers go to market as he gave us a tour of his office on the outskirts of Shenzhen: “We do more than just manufacture other people’s designs. We can take a concept and design it for manufacturing to allow someone to produce samples, small runs, and large runs that are speedy and economically viable.” Eric and his team have built an ever-expanding catalog of the most-used electronic components that are compatible with each other and that can be loaded into an automated pick-and-place printed circuit board machine. Makers that use parts from the catalog can have prototypes built and shipped on order.14 What previously took weeks and was prohibitively expensive can now be completed in hours and is affordable to any aspiring maker. As a maker scales into production, the preliminary design specifications can be tweaked to improve performance and lower cost.

bunnie and Eric, as well as the folks at Haxlr8r and PCH, are part of a community of entrepreneurs who focus on integrating design, prototyping, and manufacturing for small electronics, and making that world accessible to the growing maker populations around the globe. They host, incubate, and accelerate makers and start-ups in Shenzhen by taking them from concept to physical production, collapsing those previously separate worlds, and increasing speed, efficacy, and efficiency in the global supply chain.

A map of the maker ecosystem

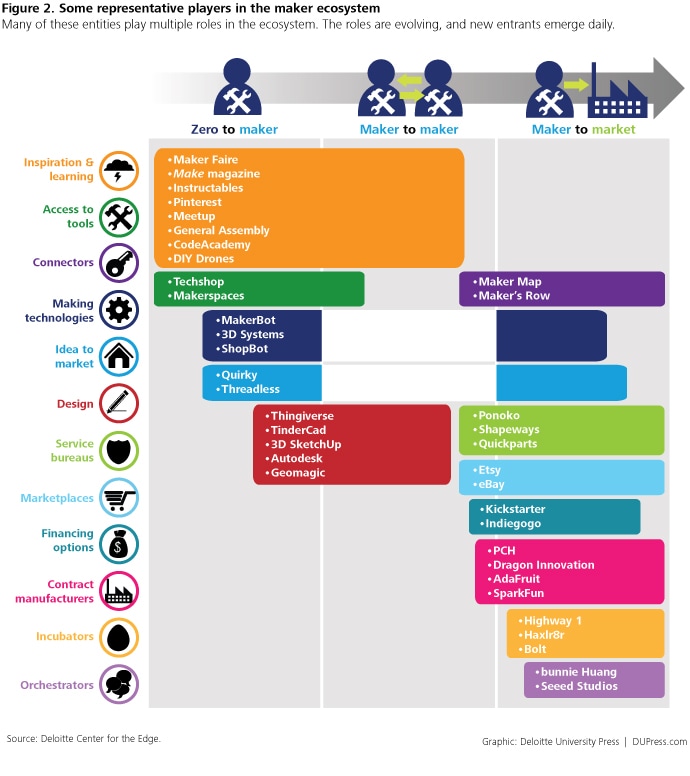

We have described the maker movement from the perspective of the makers themselves—that is, the journey that an individual makes to begin creating, to share ideas and learnings, and for some, to develop a business. Along every step of the maker spectrum, other actors in the ecosystem reinforce and amplify the movement (figure 2), often through centralized platforms that make digital resources more freely available and consolidate sources of information. Without these other communities and organizations, the movement would not have as great an impact. To understand the movement, we need to take a deeper look into all areas of the ecosystem.

Zero to maker: Going from zero to maker requires resources in two main areas: the knowledge about what to produce and how to design it; and access to machines and the skill to use them.

Imagine being led into a room with a sheet of acrylic and a laser-cutting machine. While some people might eventually craft that acrylic into a wall-mounted, back-lit triptych, many of us would be at a loss—without a pattern or design, or knowledge of how to use the laser cutter. Now, however, entire designs and machine instructions for 3-D printers, computer numerical control (CNC) cutters, and other fabrication tools can be downloaded from sites such as Thingiverse and fed directly into a waiting machine. As an individual gains skills, modeling and design software is increasingly available in inexpensive desktop versions, such as Autodesk 123D.

The second requirement is access to the tools, machines, and technologies that produce the inventions. This barrier is also lower now, as a result of more shared spaces opening up that allow access to machines on a subscription basis. A member can reserve time on a traditional industrial machine like a lathe or gain access to newer technologies like 3-D printers. Spaces such as TechShop and 100kGarages function like gyms for makers, letting individuals pay for various levels of membership to gain access to machines, classes, and workspace. These and other ecosystem players work together to lower the barriers to making, enabling more and more people to go from zero to maker.

Maker to maker: Digital communication and sharing have led to greater diversity and fidelity of what can be shared. Simple question-and-answer forums have evolved into detailed step-by-step instructions on Instructables.com and how-to videos on YouTube. These channels for learning and producing also connect makers to one another. On platforms from Thingiverse and MakerBot to DIY Drones, makers freely share their designs and allow others to modify and improve them. These sites include forums where participants answer each other’s technical questions, galleries where they share and review projects, and communities where teams form around special areas of interest. This sharing has created opportunities for entrants to contribute in multiple areas of the maker ecosystem, from marketplaces to financing to production.

This area of the maker spectrum is characterized by makers leveraging the resources of not only other makers but also those who have decided to serve the maker movement.

Maker to market: As more and more makers connect with various parts of the ecosystem, some will seek a profit and think about commercializing their inventions. The barriers to manufacturing and commercialization have been reduced. Digitization of information and rapid information transfer have lowered start-up and switching costs. In addition, digital tools—whether additive, subtractive, or assembly—have improved the fidelity of reproduction and dramatically lowered the costs associated with complexity. This means that functionality, engineering, and assembly methods can be built in during design, and smaller batches can be produced more economically. Makers can tap into this manufacturing capacity to prototype and scale their inventions.

Incubators and other intermediaries have sprung up to assist makers in refining their inventions and finding efficient ways to bring products to market. Indeed, in the last five years, crowdfunding platforms such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo have funded hundreds of millions of dollars of maker-related projects, while organizations such as Shapeways and Ponoko are allowing makers to turn complex designs into actual products.

As these makers and their inventions are supported and amplified across the ecosystem, the impact will be felt across more areas of society and business.

The self-reinforcing nature of the maker movement is manifest all along the spectrum. The desire to learn is satiated by increased flow of information through physical and virtual communities. In turn, these communities are nourished by the increasing desire to connect and contribute. The ability to solve real-world problems draws many into the global economy. As these makers and their inventions are supported and amplified across the ecosystem, the impact will be felt across more areas of society and business.

Death by a thousand cuts (and a powerful platform)

Over a million sellers have used Etsy to sell more than 100 million items collectively valued at a few billion dollars. Over 30 million members from over 200 countries purchase on Etsy. Its products range from greeting cards to jewelry, art, and clothing to housewares. Its largest growing segment is furniture.

Platforms like Etsy, along with eBay and others, are lowering barriers to entry and scale for any entrepreneur or small business. They instantly provide a global storefront with no upfront cost. Shapeways—a company that manufactures and distributes 3-D printed objects—has over 11,000 shop owners selling everything from mathematical art sculptures to drones. On Quirky you can submit a product idea and let the half-a-million members (“inventors,” as Quirky refers to them) develop and design the idea into a real product. If the product passes the stage-gate process, Quirky would then manufacture and distribute the product, including to dedicated retail shelving at Target. On Threadless, users can submit designs that are voted on, and the winning entries are made into T-shirts, sweatshirts, and posters. On deviantART, budding artists can sell their sketches and artwork.

The examples above point to the increasing number of niche providers that are competing with large companies for share of wallet. Now that building new products and reaching new customers is easier than ever, competition can and will come from everywhere, not just your biggest competitors.

The sellers of these unique products are building not just on new production and distribution platforms but also riding the trend of consumers demanding more customized products and services. In the past consumers had limited choice—buy what was mass-produced or choose from a small selection of items at local craft outlets and farmers’ markets. The advent of marketplaces on the Internet (from eBay to niche sites such as Nervous System) expanded those choices for consumers and whetted their appetite. The demand curve moved out, but the supply curve stayed put.

In the last few years the plethora of new platforms, ranging from those that inspire and teach new skills (such as Instructables and Codeacademy), to physical maker spaces that provide access to tools and mentorship, to financing options that allow hobbies to scale into businesses (such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo), to online marketplaces (such as Etsy and Threadless) have started affecting the supply curve.

In addition to these platforms, makers can use global manufacturing hotspots such as Shenzhen, China, not only to meet massive scale production but also to produce small batches more economically. Three factors play into this development: the declining cost of production to a point where small-batch production cost meets the price point of early adopters and niche consumers; small-batch or sample “factories” refining and improving their processes to reduce cost; and improved access to these factories through a network of intermediaries such as bunnie Huang, Seeed Studios, and PCH’s Highway 1. The long tail of supply now matches the long tail of demand.

The scales haven’t tipped yet. While alternatives exist to almost any mass-produced item, most US consumers haven’t yet explored the full range of possibilities. However, it is only a matter of time before large firms begin to feel the impact as multitudes of niche products collectively take market share away from generic incumbent products. Ignoring niche products won’t reverse the trend.

The long tails meet: The author’s story

My wife was giving birth to twin boys. I wanted to celebrate the occasion with a gift. Rather than a jewelry store, this time I turned to a digital marketplace for handmade goods. With a few key words and clicks, I could now look for something that was meaningful and customizable. My kids were expected in October, so I wanted something with their birth stone—opals.

The initial search returned over 68,000 results. Confining the search to “jewelry” yielded 38,000 results. “Necklace”—10,000 results. The options were beautiful but entirely too many to be helpful. But with a few more clicks, I narrowed the field to a handful of local artisans whose work I liked. After a short email exchange and a face-to-face meeting at a nearby cafe, I picked out the stones (two Australian boulder opals with blue and green flashes) and design that I wanted. Shortly after, I had a beautiful custom pendant.

—Duleesha Kulasooriya

Making something of the maker movement

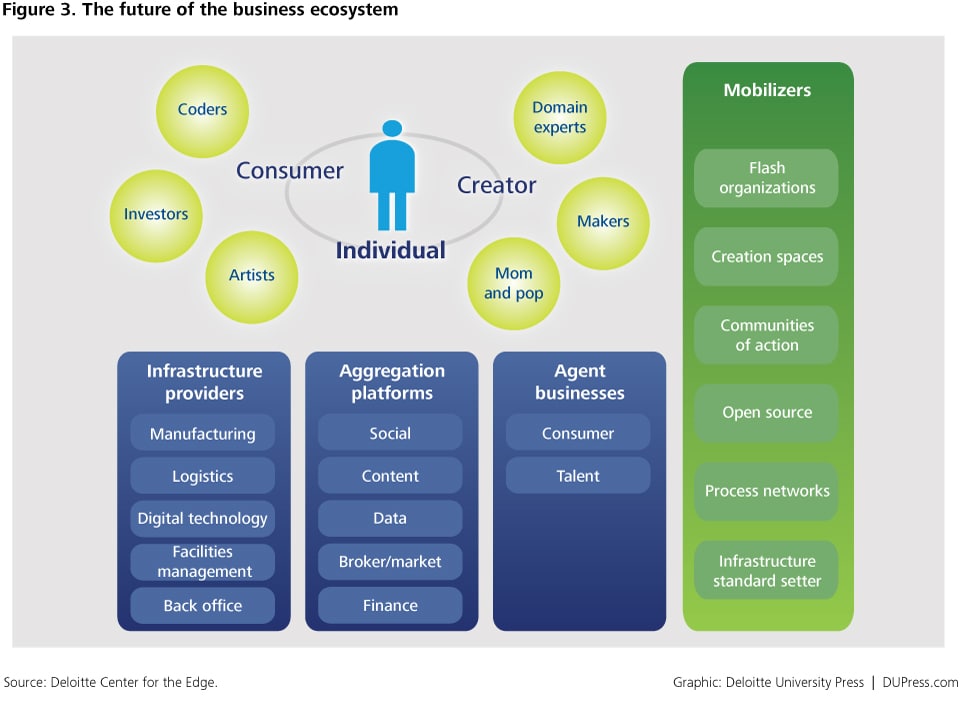

Shaped by exponential technology advances and global interconnection, the institutional landscape is increasingly bifurcated: Some areas will fragment into smaller and smaller entities, while other areas will consolidate, and only a few, large-scale entities will survive.

The increasing fragmentation of business and innovation is creating a symbiotic relationship between grassroots businesses and the large-scale platforms that enable and empower them. A platform’s power and relevance relies on the number of subscribers and their participation—the network effect. Similarly, individuals and small businesses rely on the existence and further development of these platforms to keep barriers to entry low and make scaling a business viable. The platforms grow in value with fragmentation, and the fragmented parts of the economy gain more value as the platforms expand.

As the business landscape fragments and consolidates, established firms have to find their place in the fabric. They will want to stay away from the parts of the economic landscape that are fragmenting and focus instead on the parts that are consolidating—which broadly fall into two categories: scale operators and mobilizers (figure 3).

- Scale operators provide the physical infrastructure, digital aggregation, and mass-agent capability required to support niche operators. Large physical businesses such as manufacturing, logistics, facilities management, and back-office operations will get even bigger as they support increasingly large and fragmented businesses spanning the globe. Digital aggregation platforms such as social media platforms, online marketplaces, and finance platforms will also grow in size for the same reason. And a new segment of large-scale consumer and talent agents will increase the number of options to both consume and learn.

- Mobilizers, from “flash organizations” to open source platforms to “shaping networks,” will connect niche operators with each other and with scale operators.

As the business landscape evolves, so does the rationale for large institutions. With the decreasing cost of activity coordination across independent entities, and the increasing need to continuously learn and evolve, firms exist less for scalable efficiency than for scalable learning.

The maker movement provides a few possible avenues for building agile, nimble learning organizations that scale.

1. Use the maker ecosystem to boost your sensing capabilities

Makers represent a broadly distributed innovation ecosystem. They tinker, build, market, and sell unique items. The benefits of paying attention to this ecosystem and its output include the ability to observe emerging trends and technologies within the ecosystem. Which types of items, materials, techniques, or technologies are gaining popularity? Monitoring emerging trends can allow scale operators and orchestrators to better shift resources, not only to support but also to shape these trends.

GE and Quirky

In November 2013 GE invested $30 million in the latest round of funding for Quirky, a start-up that crowdsources ideas and uses a mix of crowd and internal capabilities to develop a product from an idea to the retail shelf. More interestingly, in April 2013 GE also opened portions of its vast patent portfolio to the Quirky community for creating new products. GE’s intent is to use the Quirky community to create a portfolio of connected Internet devices (“the Internet of things”) for the consumer market. GE and Quirky members will share revenues of the resulting products, and GE will gain insights into a consumer market new to it.15

West Elm and Etsy

In the spring of 2013, Etsy, the marketplace platform for creative small businesses, launched Etsy Wholesale, “a private platform where professional buyers for boutiques and other retailers discover and connect with juried artists, designers, and vintage vendors who offer wholesale.” Having previously highlighted Etsy sellers in its catalogs and special events, West Elm signed up for the Etsy Wholesale program and is featuring groupings of local Etsy products—from handmade pottery to paper lanterns—in its stores. This has allowed West Elm to inject local character in its stores and attract consumers who are increasingly drawn to unique offerings and desire a more personal connection to the making of the items they buy.16

IKEA hackers

In 2006 an IKEA enthusiast, Mei Mei “Jules” Yap, created Ikeahackers.net after she noticed how many people were customizing off-the-shelf IKEA furniture and posting pictures online. The site has become a collection of ideas and hacks of IKEA furniture.17 As the IKEA hackers have demonstrated, the modular, assemble-at-home nature of IKEA furniture lends itself well to making custom furniture. What if IKEA created a platform of compatible parts with plans to further empower this community?

Ford and TechShop

TechShop Detroit began partly as a result of a partnership with Ford Global Technologies, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Ford Motor Company. Ford established an employee patent incentive program to encourage employee engagement in innovation efforts. Part of the premise was that a high-fidelity working prototype for a new idea has a greater chance of overcoming internal hurdles to move through the innovation funnel than a concept on paper. In the program’s first year, approximately 2,000 employees took advantage of the free three-month membership to prototype and evolve ideas. The program has led to a 50 percent increase in patentable ideas.18

Another benefit of having sensing capabilities in this ecosystem is to identify and gain access to the individuals with the most expertise and passion in any given field. This provides a broad yet deep network of talent and expertise that the company can access as needed without having to acquire that talent on a long-term basis.

Start engaging with maker communities. Give your employees access and, more importantly, permission to participate in these communities. Build feedback loops to expose the firm to what is being sensed in these communities, and use that knowledge to further develop your scale platforms.

2. Employ the same platforms (that makers use) for your own R&D

Makers are progressing from hobbyists to businesses on the back of platforms that are lowering barriers to entry. The maker community is like an open and distributed research and development (R&D) center, and at any given time it’s possible that someone is working on something that is important to a large company. Employees of large firms are mostly unaware of these platforms and opportunities, and even when they know of them, both their mindsets and the firm’s rigid processes and rules can prevent employees from taking advantage of the tools. As a result, large firms are at a disadvantage when it comes to rapid experimentation and prototyping.

The tables have turned. In the past, small firms or individuals didn’t have access to the tools or financing to build a business out of making. Today, the same practices and policies that gave large firms an advantage in the past are the ones that stifle their agility and innovative capacity. It is imperative for large firms to start using the same tools and platforms available to small firms and individuals.

Start by allowing individuals and organizations at the “edges” of your firm to experiment and learn by using these platforms. Then look to scale these edges, getting them to share their learning and drawing the rest of your firm into using these platforms and practices as well.

3. Encourage the maker mindset in your workforce

Makers are known to be creative, resourceful, and predisposed to making things happen. They are particularly adept at merging a range of technologies to solve a problem—a useful skill in today’s business environment.

Creativity is a learned and applied ability—just like product management or analytical skills. The more a person exercises the creative muscle—in work or otherwise—the stronger it gets. Being creative is an exercise in selective hoarding, exploration, experimentation, failing fast, and rapid feedback in addition to creating something new. As we move into times of constant change, a nimble, agile workforce will be required for companies to stay competitive. Finding ways to bring out the resourcefulness and the ability to integrate that is common among makers will help retrain our workforce to apply those skills to their everyday work.

Start by giving your workforce permission and support to engage in maker communities. One approach may be to subsidize memberships to maker spaces, similar to firms subsidizing gym memberships or adult learning courses. Reconsider the tightly scripted, standardized work products and processes of your organization, and look for ways to allow employees more freedom to incorporate collaborative, tinkering approaches into their daily work.

4. Rethink the enterprise (its products and assets) as a platform

Times of disruption (as the maker movement may bring) are also times of opportunity. Be proactive instead of reactive: Rather than sensing and reacting to the changes afoot, you can stake your space in the evolving value chain. Deploy platforms that can help specific segments of makers to thrive and scale.

As consumers, the maker-oriented segment wants to modify and adapt existing technology to their own needs and purposes, creating value for both the manufacturer and the consumer. By creating “hackable” interfaces in their products, companies enable makers to potentially discover new uses not conceived of by the product development team. Products can be reconceived as platforms that engage and encourage maker-oriented consumers to tailor products to the needs of individual consumers.

Underused scale infrastructure facilities—for example, manufacturing, logistics, and distribution centers—can be rented by or loaned to makers to scale their operations. Knowledge assets and resources—such as patent portfolios or the flextime of a large labor pool—can be made available for the maker population to leverage in a noncompetitive, “grow the pie” way. A company’s brand, customer relationships, and distribution channel infrastructure can create platforms that allow makers to more readily reach the markets served by the larger company. These platforms could even drive greater scale for the large company, adding revenue sources and lowering operating costs at the same time.

Some companies may even evolve into infrastructure management or customer relationship businesses and away from the design and development of new products.

Start with engaging actively in maker communities. Learn what their needs and wants are, and see what underutilized facilities and assets you could bring to support those needs. Convert these facilities and assets into platforms, and engage and encourage the maker community to build upon them. Experiment with converting some products into platforms and allowing the maker community to customize and resell them.

The current evolution of the maker movement is an early signal of the future business landscape. While we are still adjusting to and making sense of the first wave of digital disruption led by the digitization of information, disruption is now moving into the physical and product level. The broader impacts of the maker movement on business and society, and the forces accelerating it, are still uncertain. The exponential advances in digital infrastructures will fragment some portions of today’s economy and consolidate others, but which industries will be most affected is unclear. How these forces will affect manufacturing, and whether these effects will be primarily local or global, remains to be seen. The maker movement also has further implications for employment and job training. What is apparent is that the movement is both an important signal and a disruption in its own right.

Embrace the movement. Help shape its direction, and use it as a canvas to learn the contours of the world to come.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.